Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia (CEP) is an idiopathic condition characterised by extensive eosinophilic infiltration of the lung parenchyma. It typically presents with progressive dyspnoea, productive cough, fever, weight loss, and night sweats. The condition predominantly affects women, with a female-to-male ratio of 2:1,1 and is more common among non-smokers. Furthermore, CEP is frequently associated with a history of atopy and asthma.1,2

Diagnosing CEP remains challenging, as no specific biomarker has yet been identified for this disorder. Peripheral eosinophilia is a characteristic finding, often accompanied by elevated total serum immunoglobulin E (IgE) levels and acute-phase reactants. Pulmonary function tests may reveal either obstructive or restrictive patterns, making them particularly valuable for monitoring disease progression and treatment response. Radiographically, peripheral infiltrates resembling a photographic negative of pulmonary oedema are characteristic. Elevated interleukin-5 (IL-5) levels and increased eosinophil counts in both peripheral blood and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid serve as key therapeutic targets, with reductions indicating treatment efficacy. Anti-IL-5 agents inhibit eosinophil differentiation, proliferation, and activation. Histopathologically, CEP is characterised by eosinophilic and histiocytic infiltration of both interstitial and alveolar tissues (Fig. 1).

Treatment typically relies on short courses of systemic corticosteroids. However, relapses are common and often necessitate prolonged therapy, which is associated with significant long-term adverse effects. In recent years, alternative therapies such as omalizumab, mepolizumab, and benralizumab have been used off-label. Nevertheless, to date, no clinical trials to date have been registered to support their use in CEP.1

Mepolizumab is a humanised monoclonal antibody that reduces eosinophilic inflammation by inhibiting IL-5 mediated activation pathways.3

This report presents a case of corticosteroid-refractory CEP successfully treated with off-label mepolizumab, resulting in both symptomatic and analytical improvement, as well as a marked reduction in systemic corticosteroid requirements.

The patient is a 34-year-old non-smoking woman with a history of eosinophilic asthma with an allergic component since childhood. From the age of 15, her symptoms—including cough, nocturnal dyspnoea, poor exercise tolerance, sputum production, and rhinitis—worsened and became increasingly difficult to control, despite maintenance therapy with montelukast and standard inhaled treatments. She required four to five courses of corticosteroids annually due to exacerbations.

In 2007, she was hospitalised for the investigation of ground-glass pulmonary infiltrates detected in the upper lobes on computed tomography. A pulmonary biopsy revealed a histological pattern consistent with eosinophilic pneumonia (Fig. 1). Subcutaneous omalizumab (300mg/month) and budesonide/formoterol (200/6μg twice daily) inhaler therapy were initiated for her severe uncontrolled asthma, leading to improved symptom control and discontinuation of oral corticosteroids. Omalizumab was prescribed based on the patient's longstanding allergic phenotype.

She had symptomatic sensitisation to common aeroallergens—cat, dog and olive pollen—confirmed by a positive skin prick test conducted by an allergist. At that time, omalizumab was the only monoclonal antibody approved and available in our country for the treatment of severe allergic asthma. However, within a few months, severe symptoms reappeared despite good adherence to treatment, necessitating additional cycles of systemic corticosteroids (three cycles of deflazacort in the past year) (Table 1). The patient discontinued omalizumab due to a perceived lack of efficacy.

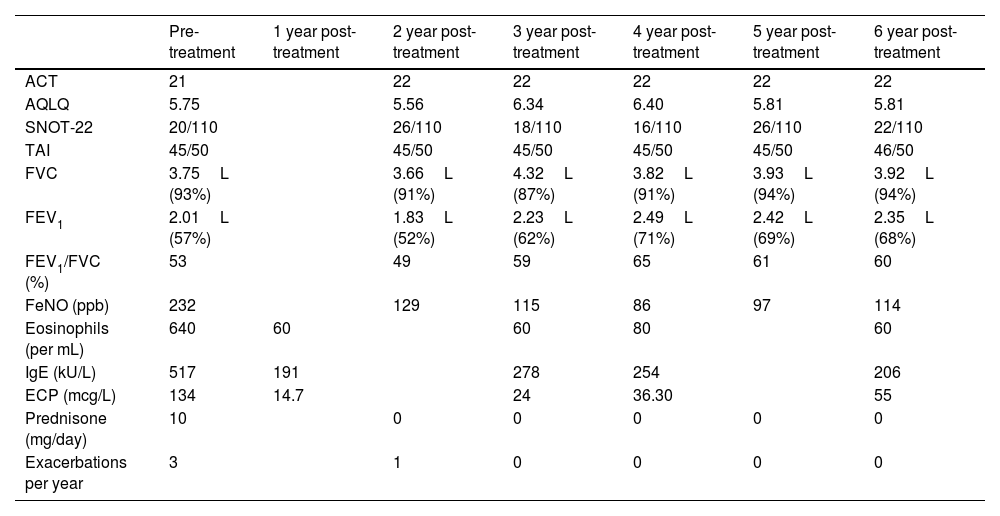

Functional respiratory tests and clinical parameters during follow-up with mepolizumab treatment.

| Pre-treatment | 1 year post-treatment | 2 year post-treatment | 3 year post-treatment | 4 year post-treatment | 5 year post-treatment | 6 year post-treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACT | 21 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 22 | |

| AQLQ | 5.75 | 5.56 | 6.34 | 6.40 | 5.81 | 5.81 | |

| SNOT-22 | 20/110 | 26/110 | 18/110 | 16/110 | 26/110 | 22/110 | |

| TAI | 45/50 | 45/50 | 45/50 | 45/50 | 45/50 | 46/50 | |

| FVC | 3.75L (93%) | 3.66L (91%) | 4.32L (87%) | 3.82L (91%) | 3.93L (94%) | 3.92L (94%) | |

| FEV1 | 2.01L (57%) | 1.83L (52%) | 2.23L (62%) | 2.49L (71%) | 2.42L (69%) | 2.35L (68%) | |

| FEV1/FVC (%) | 53 | 49 | 59 | 65 | 61 | 60 | |

| FeNO (ppb) | 232 | 129 | 115 | 86 | 97 | 114 | |

| Eosinophils (per mL) | 640 | 60 | 60 | 80 | 60 | ||

| IgE (kU/L) | 517 | 191 | 278 | 254 | 206 | ||

| ECP (mcg/L) | 134 | 14.7 | 24 | 36.30 | 55 | ||

| Prednisone (mg/day) | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Exacerbations per year | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

ACT: Asthma Control Test.

AQLQ: Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire.

SNOT: Sinonasal Outcome Test.

TAI: Test of Adherence to Inhalers.

FVC: Forced Vital Capacity.

FEV1: Forced Expiratory Volume in 1second.

FeNO: Fractional Exhaled Nitric Oxide.

In 2017, due to the persistent need for systemic and inhaled corticosteroids, mepolizumab (100mg/month) was initiated. The therapy was maintained for six years, resulting in a good clinical response and disease stabilisation (Table 1). To date, the patient has not experienced any significant adverse effects from mepolizumab.

During follow-up, sequential pulmonary function tests demonstrated progressive improvement in FEV1 (Table 1). Laboratory analyses revealed a marked reduction in eosinophil counts and activity, as measured by eosinophilic cationic protein (ECP). These findings reflect the efficacy of eosinophil-targeted therapy, clinically manifesting as reduced exacerbations and a decreased need for systemic corticosteroids.

Previous studies have reported similar outcomes. Mepolizumab therapy has been shown to significantly reduce peripheral eosinophilia4 and pulmonary infiltrates on imaging5,6 in patients with CEP. These improvements have led to better disease control, fewer exacerbations, and reduced corticosteroid dependence.7,8 Most studies also highlight the favourable safety profile of mepolizumab, with no major adverse events reported.1 Several authors have documented disease control with extended dosing intervals of up to ten weeks, compared with the standard four-week regimen.9

This case contributes relevant information to the existing literature on chronic eosinophilic pneumonia. Unlike most published reports, which include follow-up periods ranging from several months to a few years, we present a six-year follow-up with sustained clinical stability under mepolizumab treatment.

Moreover, multiple studies have explored the relationship between ECP levels and eosinophil activity in eosinophil-driven conditions such as asthma. ECP has also been proposed as a predictive biomarker of therapeutic response to biological agents, including mepolizumab, in diseases characterised by a high eosinophilic burden.10–12 In this context, we considered it particularly relevant to incorporate ECP monitoring in the follow-up of our patient, as a means of dynamically assessing eosinophilic inflammatory activity and supporting clinical decision-making regarding treatment efficacy and adjustment.

Finally, it underscores the importance of a comprehensive diagnosis through confirmatory histopathological findings of CEP in a representative lung biopsy.

Future clinical trials involving larger populations are essential to optimise dosing, duration, and safety, ultimately allowing mepolizumab to be considered a potential standard treatment for chronic eosinophilic pneumonia.

Patient consentThis case report is based on a retrospective clinical observation and does not involve any experimental intervention in humans. Therefore, formal approval from an ethics committee was not required. All identifying information has been omitted to preserve patient confidentiality. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case and accompanying clinical data, in accordance with applicable regulations.

Study approval statementEthics approval was not required because of retrospective and observational study. We did not change our daily clinical practice.

Consent to publish statementSubjects have given their written informed consent to publish their case (including publication of images).

Artificial intelligence involvementDuring the preparation of this work, the author(s) used ChatGPT (OpenAI) to assist with the revision and adaptation of the manuscript into academic British English. After using this tool, the author(s) carefully reviewed and edited the content to ensure accuracy and take full responsibility for the final version of the manuscript.

FundingThe authors declare no funding was received.

Authors’ contributionsAll authors contributed to the conception, data generation, analysis, revision, and final approval of the manuscript. María Longás and Cindy S. Aponte contributed equally as first authors.

Conflict of interestThe authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper. The intent of this policy is not to prevent authors with these relationships from publishing work, but rather to adopt transparency such that readers can make objective judgments on conclusions drawn.

Leticia De Las Vecillas, Carlos Carpio, Inés Torrado, Mihaela Ifrim, Guillermo Escuer-Albero, Rita M Regojo-Zapata, Pablo Mariscal, Elena Villamañán, Paula Granda, Javier Domínguez-Ortega.