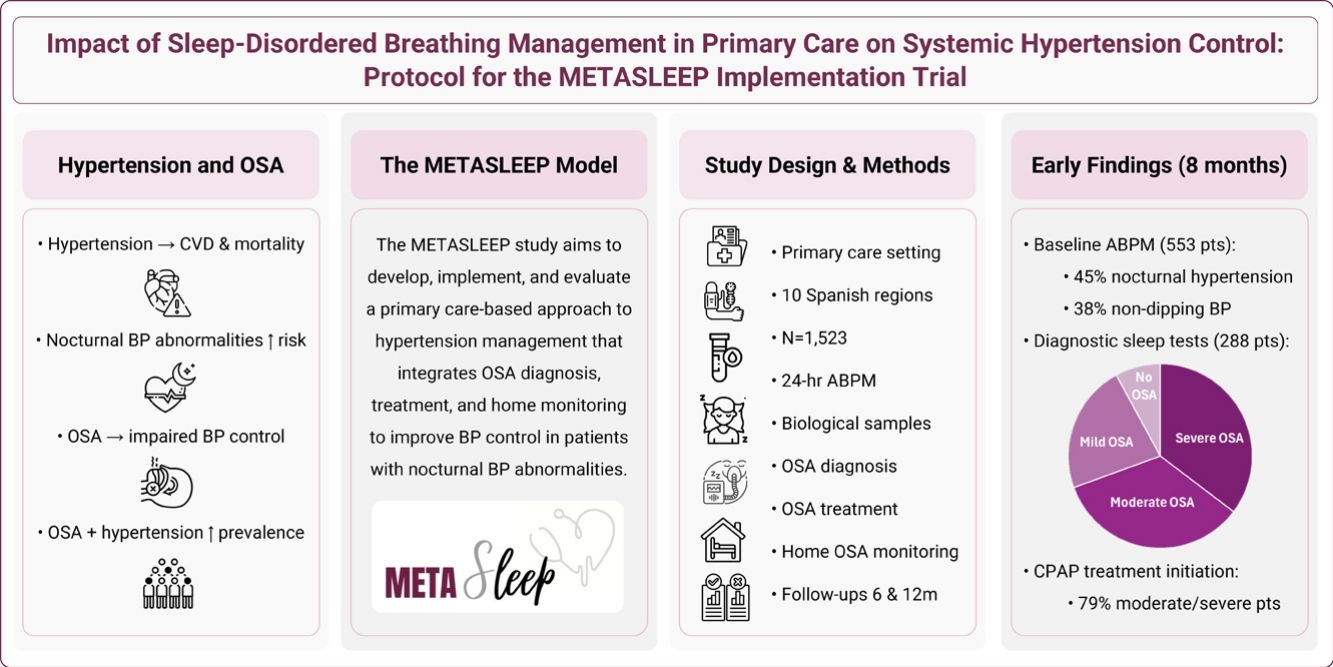

Hypertension is the leading cause of cardiovascular disease, with nocturnal blood pressure (BP) abnormalities (nocturnal hypertension and non-dipping BP) linked to heightened risk. Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), a modifiable contributor to impaired nighttime BP regulation, commonly co-occurs with hypertension. Primary care (PC) represents a strategic setting for their integrated management. The METASLEEP study aims to develop, implement, and evaluate a novel PC-based hypertension care model incorporating OSA diagnosis, treatment, and home monitoring to improve BP control.

ObjectivesTo describe the rationale, design, methodology, and baseline participant characteristics of the 2024 initiation phase of the METASLEEP trial.

Material and methodsProspective, longitudinal, real-world implementation study conducted across 10 Spanish regions (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT05986487). Adults with hypertension and no prior OSA diagnosis undergo 24-h ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) in PC (target n=1523). Participants with nocturnal hypertension and/or non-dippers receive PC-led OSA diagnostic testing, treatment, and home monitoring via an under-mattress sensor. Follow-ups at 6 and 12 months evaluate changes in nighttime BP (primary) and other clinical outcomes.

ResultsBy end of 2024, 553 patients completed baseline ABPM. Of these, 288 (52.1%) showed nocturnal BP abnormalities: 248 (44.8%) had nocturnal hypertension and 211(38.4%) were non-dippers. Participants were middle-aged, overweight, and frequently had comorbid dyslipidemia, obesity, and diabetes. OSA prevalence was 22.6% mild, 34.1% moderate, and 35.3% severe. CPAP treatment was initiated in 79.4% of moderate-to-severe cases.

ConclusionsMETASLEEP introduces a novel PC-based model integrating OSA diagnosis and management within hypertension care. Early data reveal notably high prevalence of undiagnosed OSA in hypertensive patients.

La hipertensión es la principal causa de enfermedad cardiovascular, y las anomalías nocturnas de la presión arterial (PA) (hipertensión nocturna y PA non-dipping) se asocian a un mayor riesgo. La apnea obstructiva del sueño (AOS), un factor modificable que contribuye a la alteración de la regulación nocturna de la PA, suele coexistir con la hipertensión. La atención primaria (AP) representa un entorno estratégico para su manejo integrado. El estudio METASLEEP tiene como objetivo desarrollar, implementar y evaluar un nuevo modelo de atención a la hipertensión basado en AP que incorpore el diagnóstico, el tratamiento y la monitorización domiciliaria de la AOS para mejorar el control de la PA.

ObjetivosDescribir la justificación, el diseño, la metodología y las características basales de los participantes de la fase de inicio de 2024 del ensayo METASLEEP.

Material y métodosEstudio prospectivo y longitudinal de implementación en la práctica clínica real, realizado en 10 comunidades autónomas españolas (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT05986487). Adultos con hipertensión y sin diagnóstico previo de AOS se someten a monitorización ambulatoria de la PA (MAPA) de 24 horas en AP (n objetivo=1523). Los participantes con hipertensión nocturna y/o non-dippers reciben pruebas diagnósticas de AOS dirigidas por AP, tratamiento y monitorización domiciliaria a través de un sensor debajo del colchón. Los seguimientos a los 6 y 12 meses evalúan los cambios en la PA nocturna (resultado principal) y otros resultados clínicos.

ResultadosA finales de 2024, 553 pacientes completaron la MAPA basal. De estos, 288 (52,1%) mostraron anomalías de la PA nocturna: 248 (44,8%) tenían hipertensión nocturna y 211 (38,4%) eran non-dippers. Los participantes eran de mediana edad, con sobrepeso y con frecuencia presentaban dislipidemia, obesidad y diabetes comórbidas. La prevalencia de AOS fue del 22,6% leve, del 34,1% moderada y del 35,3% grave. El tratamiento con CPAP se inició en el 79,4% de los casos moderados a graves.

ConclusionesMETASLEEP introduce un novedoso modelo basado en AP que integra el diagnóstico y el tratamiento de la AOS en la atención de la hipertensión. Los primeros datos revelan una prevalencia notablemente alta de AOS no diagnosticada en pacientes hipertensos.

High blood pressure (BP), defined as BP >140/90mmHg, is the leading global cause of death and disability-adjusted life years (DALYs)1 and the major modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD)2 and stroke.3 The prevalence of hypertension has doubled in the past several decades reaching epidemic proportions, currently affecting approximately one-third of the world's adult population.4 Pharmacological treatment of hypertension is often insufficient to optimally reduce BP, with less than a quarter of patients reaching BP targets for control.4 This positions hypertension as a critical public health challenge.

Hypertension guidelines recommend that diagnosis should be based on out-of-office measurements using 24-h ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM).5 ABPM parameters have consistently demonstrated to have a closer relationship with fatal and morbid events than office BP parameters.6 Among these indices, nighttime BP is the most sensitive predictor of cardiovascular morbi-mortality.7 In addition to absolute BP levels during sleep, the day-to-night BP ratio is also a key predictor of outcomes.8 Patients with a blunted nighttime BP decline (i.e., non-dipping circadian pattern) face an increased risk of cardiovascular events, hypertension-mediated organ damage, and all-cause mortality, even in the absence of elevated nocturnal BP.9 Nocturnal hypertension (average nighttime BP ≥120/70mmHg) and non-dipping BP (nighttime-to-daytime ratio of mean BP >0.9) often co-occur,10 representing a high-risk BP phenotype that is greatly prevalent in the general11 and hypertensive populations.12

Among the recognized causes of impaired nocturnal BP regulation, sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) stands out as a major contributing factor.13 Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), the most common form of SDB, is a clinical condition characterized by repetitive episodes of upper airway collapse during sleep.14 In addition to triggering excessive daytime sleepiness, diminished quality of life, and a spectrum of cardiometabolic and neurocognitive sequelae, SDB disrupts the physiological nocturnal decline in BP.15 Consequently, it imposes a significant risk for developing nocturnal hypertension and abnormal nocturnal BP dipping.16 OSA is highly prevalent worldwide, affecting over one billion middle-aged adults.17 This prevalence markedly increases among individuals with hypertension (30–80%), being most common in individuals with nocturnal hypertension18 and non-dippers,19 which are recognized in hypertension guidelines as cases where OSA should be suspected.5

Effective treatment of SDB significantly reduces systemic BP, especially nighttime BP, and improves nocturnal BP patterns in patients with hypertension.20 An impaired nocturnal BP profile is a major determinant of BP response to OSA treatment in hypertensive patients.21 Given that targeting sleep is considered a new frontier in cardiovascular prevention,22 recognition and treatment of SDB, as a known cause of nocturnal BP impairment, can play a crucial role in achieving BP control and reducing subsequent cardiovascular risk.23 Hypertension and OSA are frequently encountered in primary care (PC) and often coexist, thus general practitioners are ideally placed to lead the joint management of these conditions. Solid evidence demonstrates that PC-led management is a cost-effective alternative to specialized, sleep-unit-based management of OSA.24 PC models have proven to generate substantial economic savings without resulting in worse disease outcomes or lower treatment compliance compared to specialist care,25 providing robust support for the implementation of PC-based OSA management.

Under the premise that SDB constitutes a modifiable risk factor for impaired nighttime BP, we hypothesize that the identification of nocturnal BP abnormalities, followed by diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring of SDB within PC, is a feasible and effective model to improve BP control and therefore reduce CVD risk. Under the need for studies to test this PC-based hypertension management system, we are undertaking the METASLEEP trial. In the current article, we report on the start of the METASLEEP study, describe its rationale, design, methodology, and protocol, and discuss its novelty and projected pragmatic relevance. In addition, we describe the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of participants who underwent the METASLEEP model of care for hypertension during 2024.

Study objectivesThe overarching aim of the study is to develop, implement, and evaluate the METASLEEP model, a novel PC-based approach to hypertension management that integrates the diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring of SDB in patients with nocturnal BP abnormalities. (i) The primary objective is to determine whether the METASLEEP model leads to significant and clinically meaningful improvements in BP control, as measured by the change in mean nighttime BP at 12 months (primary outcome). Secondary objectives include: (ii) to evaluate the impact of the model on additional health outcomes, including office and ambulatory BP parameters, use of BP-lowering medications, SDB-related symptoms, sleepiness, sleep health and quality, quality of life, anthropometric measurements, physical activity, and biochemical parameters; (iii) to assess the feasibility and acceptability of the model among patients, PC professionals, and stakeholders; (iv) to determine the cost-effectiveness of the model via health economic analyses; (v) to evaluate baseline differences in biomarker profiles, including circulating biomarkers and gut microbiota, between patients with and without OSA, and to assess changes following OSA-treatment; (vi) to compare study outcomes at 6- and 12-months between treated and untreated OSA patients; (vii) to identify clinical and molecular endophenotypes associated with maximized BP response to OSA treatment to inform prediction models for future targeted interventions.

Material and methodsStudy designMETASLEEP is a multicenter, prospective, longitudinal, real-world implementation study evaluating a novel hypertension management system that integrates the diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring of SDB in PC (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT05986487). The study is being conducted across 26 PC centers and 11 associated sleep units across 10 regions of Spain (Table 1). The study is led by the coordinating center (Hospital Arnau de Vilanova and Santa María de Lleida/Institut de Recerca Biomèdica de Lleida), which oversees all study procedures. The first participant was enrolled on 18/04/2024, and study completion is anticipated in the first quarter of 2026.

Participating centers and current recruitment rates in the METASLEEP trial as of December 2024.

| Region and center | Recruited participants |

|---|---|

| Catalunya (Lleida) | 67 |

| Hospital Universitari Arnau de Vilanova (HUAV) | |

| Hospital Universitari de Santa Maria (HUSM) | |

| Centre d’Atenció Primària de Mollerussa | |

| Centre d’Atenció Primària Bordeta | |

| Centre d’Atenció Primària Balàfia – Pardinyes – Secà de Sant Pere | |

| Catalunya (Tortosa) | 83 |

| Hospital de Tortosa Verge de la Cinta (HTVC) | |

| Centre d’Atenció Primària El Temple | |

| Centre d’Atenció Primària L’Ametlla de Mar | |

| Extremadura | 55 |

| Hospital San Pedro de Alcántara (HSA) | |

| Centro de Salud Manuel Encinas | |

| Centro de Salud San Jorge | |

| Andalucía | 50 |

| Hospital Virgen del Rocío (HVR) | |

| Centro de Salud Camas | |

| Castilla-La Mancha | 95 |

| Hospital de Guadalajara (HGU) | |

| Centro de Salud Cervantes | |

| País Vasco | 9 |

| Hospital Universitario Araba (HUA) | |

| Centro de Salud La Habana-Cuba | |

| Centro de Salud Lakuabizkarrra | |

| Centro de Salud Olaguibel | |

| Comunidad de Madrid | 78 |

| Hospital Ramón y Cajal (HRC) | |

| Centro de Salud Los Alpes | |

| Centro de Salud García Noblejas | |

| Comunidad Valenciana | 44 |

| Hospital Sant Joan de Alicante (HSJA) | |

| Centro de Salud Cabo Huerta | |

| Centro de Salud Campello | |

| La Rioja | 13 |

| Hospital Universitario San Pedro (HUSP) | |

| Centro de Salud Joaquín Elizalde | |

| Centro de Salud Espartero | |

| Centro de Salud Rodríguez Paterna | |

| Centro de Salud Gonzalo Berceo | |

| Islas Baleares | 56 |

| Hospital Son Espases (HSE) | |

| Centro de Salud Coll d’en Rabassa | |

| Centro de Salud Pere Garau | |

| Centro de Salud Son Pisà | |

| Cantabria | 3 |

| Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla (HMV) | |

| Centro de Salud La Marina | |

| Centro de Salud Astillero | |

| Centro de Salud Selaya | |

The METASLEEP study includes adult patients attending routine visits at their PC health clinic with a confirmed diagnosis of systemic hypertension, according to current guidelines (office BP ≥140/90mmHg).5 Eligible patients must have no prior diagnosis of SDB and no history of treatment for sleep disorders. Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria of the study population are outlined in Table 2.

Eligibility criteria for enrolment in the METASLEEP study.

| Inclusion criteria |

| Adults aged ≥18 years. |

| Diagnosed with systemic hypertension as determined by standard clinical guidelines. |

| Regularly attending primary care centers in the participating network. |

| Provided informed consent for study participation and biological sample collection. |

| Exclusion criteria |

| Prior diagnosis of sleep-disordered breathing. |

| Active treatment with continuous positive airway pressure or other sleep disorder therapies. |

| Employment in fixed night shifts. |

| Severe chronic diseases with a limiting prognosis. |

| Significant psychophysical limitations preventing the completion of study procedures. |

The study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of coordinating center (Hospital Arnau de Vilanova and Santa María de Lleida/Institut de Recerca Biomèdica de Lleida) with reference number CEIC-2819). All participants provide written informed consent to participate in the study. The trial is conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the Good Clinical Practice guidelines of each participating center, and all relevant Spanish and European regulations for biomedical research. The project is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov with the identifier NCT05986487.

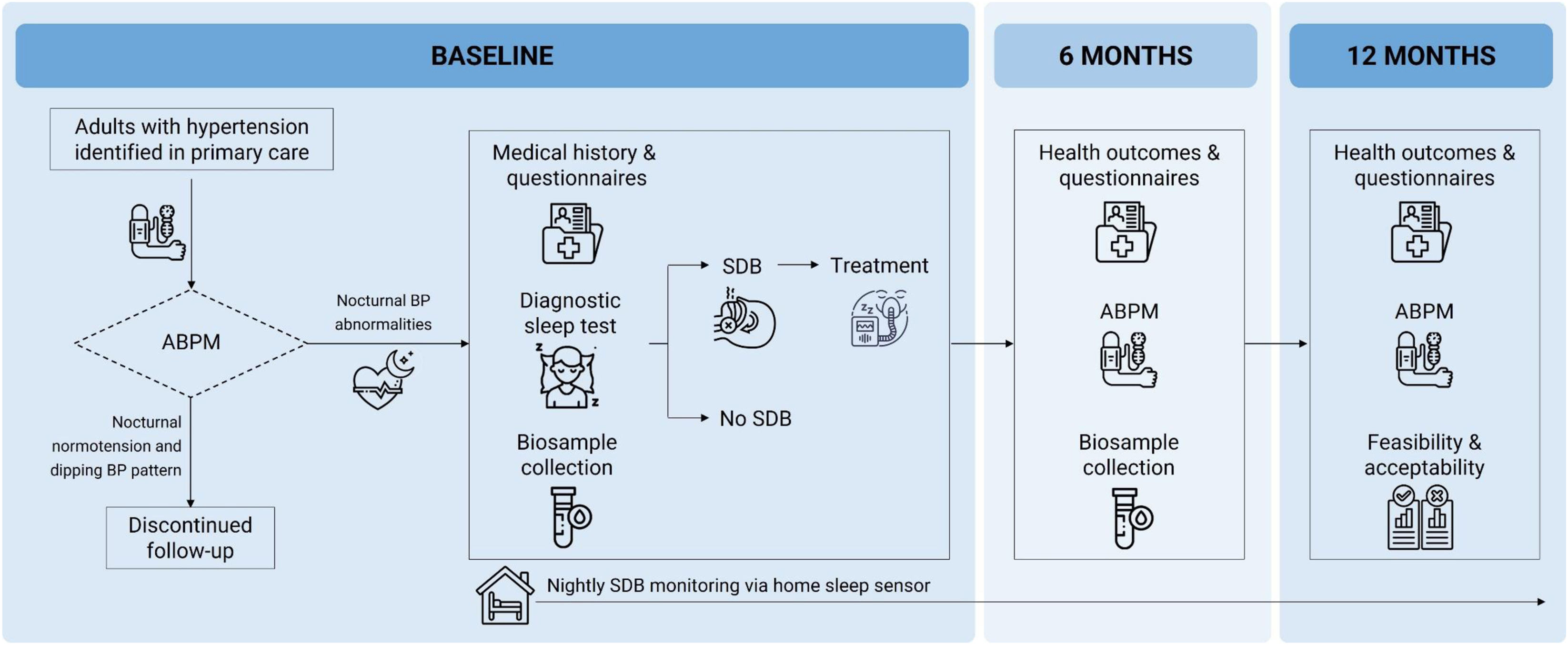

Data collectionAn overview of the study assessments and procedures is presented in Fig. 1.

Overview of the METASLEEP model of care for hypertension. Adult patients with a diagnosis of hypertension identified in primary care undergo 24-h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) to detect nocturnal blood pressure (BP) abnormalities. Participants with nocturnal hypertension (nighttime BP ≥120/70mmHg) and/or a non-dipping BP pattern (nighttime-to-daytime ratio of mean BP >0.9) proceed to diagnostic seep testing for sleep-disordered breathing (SDB), alongside clinical evaluations and biosample collection. Participants diagnosed with SDB receive standard-of-care treatment and management. Follow-up visits at 6 and 12 months include repeated 24-h ABPM, health outcomes assessments, and additional biosample collection (at 6-months only). Continuous, home-based monitoring of SDB is performed throughout the study period via an under-mattress sleep sensor.

Hypertensive participants identified in PC who meet the selection criteria (Table 2) undergo 24-h ABPM (Ontrak ABP monitor, Spacelabs Healthcare, OSI Systems, California, USA), following current hypertension guidelines.5 Participants who present both nocturnal normotension (nighttime BP <120/70mmHg) and a dipping circadian BP pattern (nighttime-to-daytime ratio of mean BP ≤0.9) conclude their participation at this stage, with no further data collected. Those with nocturnal BP abnormalities, i.e. nocturnal hypertension (nighttime BP ≥120/70mmHg) and/or a non-dipping BP pattern (nighttime-to-daytime ratio of mean BP >0.9), proceed to a diagnostic sleep study along with baseline assessments, which are completed within two weeks.

Anthropometric measurements include weight, height, body mass index (BMI), and neck circumference. Medical history, comorbidities (e.g., diabetes, dyslipidemia, chronic kidney disease), and current medications (e.g., antihypertensive and lipid-lowering agents), are retrieved from clinical records. Participants complete lifestyle questionnaires addressing smoking status, caffein and alcohol consumption, dietary habits, and physical activity. Female participants provide additional information regarding menopausal status, including age of onset and use of hormone replacement therapy. Validated instruments are used to assess SDB-symptoms, sleepiness, sleep health and quality, and quality of life, including the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), and EUROqol-5D.

A diagnostic sleep study is conducted, supported by a sleep clinic affiliated with each participating PC practice, following best standard care at each site. Sleep testing is performed either in-lab via polysomnography or at home via respiratory polygraphy (Alice NightOne, Philips, Amsterdam, Netherlands) or a validated wearable device such as WatchPAT (Itamar Medical Ltd., Caesarea, Israel).26 OSA diagnosis and severity are determined according Spanish clinical guidelines,27 based on the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI): mild (AHI 5–15), moderate (AHI 15–30), and severe (AHI >30events/h). Participants with a clinical diagnosis of OSA are offered the standard treatment options, or a combination of them, based on the physician's discretion27: (i) continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), with titration methods that may be automatic, via polysomnography, or empirical; (ii) nutritional counselling and dietary adjustments: (iii) mandibular advancement device (MAD); (iv) positional therapy. All patients treated with CPAP were telemonitored. Additionally, participants are offered home-based OSA monitoring using a validated and FDA-cleared under-mattress sleep sensor (Withings Sleep Analyzer/Sleep Rx, Withings Health Solutions, France).28 This nearable device uses ballistography, sound signals, and machine-learning algorithms to estimate sleep parameters, including the AHI, with high-correlation to gold-standard polysomnography.29

Fasting blood, urine, and stool samples are collected. Standard biochemical blood tests include glucose, creatinine, urea, sodium, potassium, uric acid, triglycerides, total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, AST, ALT, calcium, phosphorus, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), and complete blood count. Additional samples are collected for molecular and microbiota analyses, including two 6mL serum tubes, two 6mL EDTA-K3 plasma/DNA tubes, one 2.5mL Tempus™ RNA tube, one 3mL urine tube, and a stool sample. All samples are processed following an identical standard procedure and immediately stored at −80°C at the respective hospital center. Blood and urine samples are later transferred to the coordinating biobank at the Institut de Recerca Biomèdica de Lleida (B.0000682; Biobanks’ PlatformPT13/0010/0014) for long-term storage and analysis. Stool samples are transferred to the CIBERES biobank at Palma de Mallorca (Pulmonary Biobank Consortium) for processing and long-term storage and analysis.

Follow-up evaluationsFollow-up evaluations are conducted at 6 and 12 months. At both visits, 24-h ABPM is repeated to assess changes in ambulatory BP parameters, including 24-h mean, systolic, and diastolic BP; daytime mean, systolic, and diastolic BP, nighttime mean, systolic, and diastolic BP; heart rate; BP variability; nocturnal hypertension status; dipping ratio and dipping status. Comprehensive clinical reassessments are also performed, covering anthropometric measurements, medical history, lifestyle behaviors, and medication use. Participants complete the same set of questionnaires administered at baseline. SDB treatment status and adherence are reviewed at each follow-up. At the 6-month visit, fasting blood, urine, and stool samples are collected. Throughout the study period, participants are continuously monitored at home via an under-mattress sleep sensor, providing nightly objective data on sleep parameters including OSA severity. Upon study completion, participants and PC clinicians are invited to complete questionnaires and participate in interviews to evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of the METASLEEP model from the perspectives of both consumers and health providers. A resource-use questionnaire is also administered to inform cost-effectiveness analyses through health economics modelling.

Data managementAll data are securely stored in the REDCap database, hosted on the servers of the Institut de Recerca Biomèdica de Lleida. This platform ensures systematic and confidential collection of data, with access restricted to authorized researchers full audit trails for all user activity. In parallel, raw data from ABPM measurements, diagnostic sleep studies, under-mattress sensors, and CPAP use (where applicable) are stored within the dedicated xCare30 platform developed for the project by EURECAT. xCare supports ETL (Extract, Transform, Load) processes, enabling the automated integration of data from multiple sources (databases, device files, and APIs). Data are cleaned, formatted, and transformed to meet predefined standards and then loaded into a secure data warehouse optimized for subsequent analysis and reporting.

Data analysis and sample size calculationSample size calculationThe sample size was determined based on the objective with the most stringent statistical requirements. Assuming a two-sided test with an alpha risk of 0.05 and a beta risk below 0.2, and accounting for a 15% dropout rate, a total of 146 subjects per group are needed to detect a clinically significant 3mmHg reduction in the nighttime mean blood pressure measured (measured by ABPM at 12 months of follow-up) between treated and untreated OSA participants. This calculation was based on prior evidence suggesting a common standard deviation of 8.9mmHg and a correlation of 0.55 between baseline and follow-up BP measurements.21 To reach this target, initial screening of 1523 hypertensive patients is needed. Based on conservative estimates, approximately 40% (n=609) were estimated to present nocturnal BP abnormalities (nocturnal hypertension and/or a non-dipper circadian pattern) on the baseline 24-h ABPM.31 Among these, approximately 60% (n=365) were anticipated to be diagnosed with OSA, and of those, 40% were anticipated to initiate CPAP treatment, yielding the required 146 participant per group (treated and untreated OSA).32

Statistical analysisTo evaluate the primary objective, changes in nighttime BP from baseline to 12 months will be analyzed using a paired t-test for normally distributed data or the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for non-normal distributions. Results will be reported as mean differences with corresponding 95% confidence intervals. Longitudinal changes across baseline, 6 months, and 12 months will be evaluated using linear mixed-effects models. For secondary objectives, comparisons between groups at 12 months will be conducted: continuous variables (e.g., ABPM parameters, quality of life scores, sleep quality indices) will be analyzed using independent t-tests or the Mann–Whitney U test, as appropriate based on data distribution. Categorical variables will be compared using the chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test as appropriate. To control for potential confounding factors, multivariable linear or logistic regression models will be employed, incorporating relevant baseline covariates (e.g., age, sex, baseline outcome values). Adjusted estimates (e.g., mean differences or odds ratios) will be presented with corresponding 95% confidence intervals. Cost-effectiveness analyses will be conducted from the healthcare system perspective. The primary economic outcome will be the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), calculated as the difference in mean costs between groups divided by the difference in quality-adjusted life years (QALYs). All analyses will be performed using R.33 Qualitative data from focus groups and interviews will be recorded and transcribed verbatim by an external professional and analyzed via thematic content analysis. Results will be triangulated by three members of the research team.

ResultsDuring the 2024 inclusion period (∼8 months), 553 participants underwent 24-h ABPM in the PC setting (48.6% women, median age 64.0 [56.0;71.0] years). Recruitment rates by region for 2024 are detailed in Table 1. The prevalence of nocturnal hypertension and non-dipping BP pattern were 44.85% and 38.46%, respectively. Overall, 288 participants (52.08%) exhibited nocturnal BP impairments at baseline, with both nocturnal hypertension and non-dipping BP co-existing in 59.4% of the cases. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of participants with nocturnal BP impairments who were tested for SDB are summarized in Table 3. Participants were predominantly middle-aged (median age 64.0 [55.0;70.2] years) and overweight (median BMI 28.9 [26.3;32.3] kg/m2). Women accounted for 42.7%. The most prevalent comorbidities were dyslipidemia (46.2%), obesity (40.9%), and diabetes (22.9%). At baseline, 90.6% of participants reported taking BP-lowering medications. The median AHI was 23.6 [12.8;35.9] events/h; 20 (7.94%) participants had no OSA, 57 (22.6%) had mild OSA, 86 (34.1%) moderate OSA, and 89 (35.3%) severe OSA. CPAP was initiated as the first-line treatment in 139 participants, representing 79.4% of those with moderate-to-severe OSA. Blood and urine samples were collected at baseline for 264 participants. Stool samples were collected at baseline for 116 participants.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of participants who underwent the METASLEEP model of care for hypertension during the 2024 inclusion period (∼8 months).

| Participants with nocturnal blood pressure impairments*n=288 | |

|---|---|

| Clinical data | |

| Demographic/anthropometric | |

| Age, years | 64.0 [55.0;70.2] |

| Sex | |

| Male | 165 (57.3%) |

| Female | 123 (42.7%) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28.9 [26.3;32.3] |

| Neck circumference, cm | 40.0 [37.0;42.1] |

| Smoking | |

| Never | 112 (42.6%) |

| Former | 97 (36.9%) |

| Current | 54 (20.5%) |

| Alcohol intake | |

| No | 178 (67.7%) |

| Yes | 85 (32.3%) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Cardiovascular disease | 46 (17.3%) |

| Respiratory disease | 45 (16.9%) |

| Neurologic disease | 19 (7.17%) |

| Diabetes | 61 (22.9%) |

| Obesity | 108 (40.9%) |

| Dyslipidemia | 123 (46.2%) |

| Medication intake | |

| Any antihypertensive treatment | 241 (90.6%) |

| Diuretics | 72 (27.1%) |

| Calcium channel blockers | 53 (19.9%) |

| Beta-blockers | 29 (10.9%) |

| Angiotensin II receptor blockers | 97 (36.5%) |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors | 117 (44.0%) |

| Alpha-blockers | 9 (3.38%) |

| Direct renin inhibitors | 0 |

| Aldosterone receptor antagonists | 6 (2.26%) |

| Vasodilators | 0 |

| Lipid-lowering agents | 112 (42.3%) |

| Insulin | 23 (8.71%) |

| Antiplatelet drugs | 24 (9.09%) |

| Anticoagulants | 18 (6.79%) |

| Bronchodilators | 36 (13.7%) |

| Benzodiazepines | 40 (15.1%) |

| Ambulatory blood pressure data | |

| 24-h blood pressure | |

| Mean, mmHg | 104 [98.2;109] |

| Systolic, mmHg | 130 [122;137] |

| Diastolic, mmHg | 78.5 [71.6;83.2] |

| Daytime blood pressure | |

| Mean, mmHg | 106 [99.6;111] |

| Systolic, mmHg | 132 [123;139] |

| Diastolic, mmHg | 80.1 [73.0;85.5] |

| Nighttime blood pressure | |

| Mean, mmHg | 97.5 [92.6;104] |

| Systolic, mmHg | 123 [115;133] |

| Diastolic, mmHg | 72.5 [67.3;76.9] |

| Nocturnal hypertension status | |

| Nocturnal hypertensive | 248 (86.1%) |

| Nocturnal normotensive | 40 (13.9%) |

| Blood pressure dipping | |

| Dipping ratio | 0.93 [0.90;0.97] |

| Dipper | 77 (26.7%) |

| Non-dipper | 211 (73.3%) |

| Sleep data | |

| Epworth Sleepiness Scale | 7.00 [4.00;10.0] |

| Insomnia Severity Index | 7.00 [2.00;12.0] |

| Apnea-hypopnea index, events/h | 23.6 [12.8;35.9] |

| OSA diagnosis | |

| No OSA | 20 (7.94%) |

| Mild OSA | 57 (22.6%) |

| Moderate OSA | 86 (34.1%) |

| Severe OSA | 89 (35.3%) |

| Treatment indication for OSA | |

| CPAP | 139 (53.1%) |

Nocturnal blood pressure (BP) impairment at baseline is defined as the presence of nocturnal hypertension (nighttime BP ≥120/70mmHg) and/or a non-dipping BP pattern (nighttime-to-daytime ratio of mean BP >0.9), assessed via 24-h ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM). Dara are presented as n (%) for categorical variables and median [p25;p75] for continuous variables.

The METASLEEP trial addresses a critical and underexplored gap in hypertension care by introducing a pragmatic and scalable model that integrates SDB diagnosis, treatment, and home monitoring into routine PC practice. Given the global burden of hypertension and the well-established association between nocturnal BP abnormalities and elevated cardiovascular risk, targeting modifiable contributors such as OSA represents a promising and necessary strategy to improve long-term clinical outcomes. Baseline findings from the 2024 recruitment phase reinforce the clinical relevance of this approach. Over half of screened participants exhibited nocturnal BP impairments in a real-world hypertensive population managed in PC. Among these, OSA was highly prevalent, with moderate-to-severe cases representing nearly 70%. These initial findings underscore the significant burden of undiagnosed SDB in this population and highlight PC as a strategic setting for integrated identification and intervention. The high rate of OSA treatment initiation reflects the engagement and readiness of both patients and providers to adopt an integrated hypertension and OSA care pathway.

Key strengths of the project, beyond its multicentric design, include the capacity for continuous, real-time nightly OSA monitoring in the home via an under-mattress sensor. This approach enables the identification of night-to-night OSA variability and facilitates longitudinal monitoring of treatment efficiency.34 Additionally, qualitative data from interviews with participants and clinicians will provide insights into barriers and facilitators for scaling the tested model of care. Other strengths include the collection of raw sleep and 24-h BP data, as well as a range of biological samples to support endo-phenotyping and development of precision medicine approaches for personalized patient care.35–38 Limitations of the study include its observational design and the potential for selection bias inherent in real-world recruitment, which may limit generalizability. Additional limitations involve variability in diagnostic modalities across centres, including home vs. in-lab sleep tests, as well as potential inconsistencies in adherence to OSA treatments. The multicentre framework and robust data analysis protocols are designed to mitigate these factors and enhance generalizability, while the real-world context provides a valuable opportunity to assess relevant clinical outcomes in a real-life scenario.39 Several implementation challenges have emerged during the early phases of the study. Delays in ethics approvals across participating centres and protracted administrative processes for institutional agreements significantly slowed trial initiation, ultimately limiting follow-up to one year, which may be insufficient to capture long-term cardiovascular outcomes. Recruitment rates were further affected by structural limitations within the primary care system, including high clinical staff turnover and restricted time for research activities due to heavy clinical workloads.

ConclusionsAs the METASLEEP study advances, ongoing longitudinal follow-up will provide essential evidence on the effectiveness, scalability, and cost-efficiency of integrating SDB management into hypertension care within PC settings. These findings may be instrumental in shaping future clinical guidelines, guiding resource allocation, and ultimately reducing the burden of CVD through personalized patient care.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing processNone declared.

FundingProject PMP22/00030 funded by Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) and the European Union NextGenerationEU, which funds the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF); Societat Catalana de Pneumologia (beca ESTEVE TEIJIN “TERÀPIES RESPIRATÒRIES DOMICILIÀRIES” 2024); Sociedad Española de Neumología y Cirugía Torácica (convocatoria beca SEPAR 2023: 1405/2023); The study funders have no role in the study design; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing of reports; or decision to submit reports for publication.

Authors’ contributionsConceptualisation: LP, IDB, AMM, MSdT, FB, and JdB. Recruitment and clinical evaluation: GT, AAF, CCE, ICP, IB, CE, MG, OM, AR, FRC, MASQ and FB. Data management and statistical analyses: IDB, AMM, OCS, IJG, and EGL. Data interpretation: LP, IDB, IJG, EGL, MSdT, FB, and JdB. Initial manuscript drafting: LP and JdB. Manuscript revision: all authors. All authors had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare not having any conflicts of interest that may be considered to influence directly or indirectly the content of the manuscript.

FB is supported by the ICREA Academia program, Generalitat de Catalunya. JdB acknowledges Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII): Miguel Servet 2019:CP19/00108, co-funded by the European Social Fund (ESF), “Investing in your future”. I.J.-G. was supported by Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII): PFIS 2024: FI24/00084, co-funded by the European Union. MSdlT received financial support from a “Ramón y Cajal” grant (RYC2019-027831-I) from the “Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación – Agencia Estatal de Investigación” cofunded by the European Social Fund (ESF)/“Investing in your future”.

Laura Pozuelo, Cristiano Van Zeller, Sara Gonzalez, Begoña Brusint, Irene Moratinos, Lourdes Botanes, Irene Duque, Cristina Santos, Eduardo Jaramillo, Silvia López, Yolanda de Don Pedro, Bárbara Luna, Sonia Camaño, Ignacio Arribas, Reyes Nicolás, Esther Solano, Leticia Álvarez, Dolores Retuerta, Laura Silgado, Esther Viejo, Sofía Romero, Pilar Resano, María Castillo, José Luis Izquierdo, Gabriel Arriba, Carina Aguilar Martín, Nerea Bueno Hernández, Alessandra Queiroga Gonçalves, Esther Sauras-Colón, Jael Lorca-Cabrera, Marylène Lejeune, Zojaina Hernández Rojas, Mercè Ribes Pedret, Elisabet Martí Solé, Daniela Domenica Montalvo Barrera, Juan Manuel Carrera Ortíz, Sonia Baset Martínez, Rosa Caballol Angelats, Manuel Vicente Maestro Ibáñez, Núria Manchó Casadesús, Inmaculada Salvador-Adell, Mireia Serra-Fortuny, Luis Adolfo Urrelo Cerrón, Yessenia Flores Martínez, Eusebi Chiner, Violeta Esteban, Javier Puentes, Juan Fernando Masa, Elisabet Uribe, Vanessa Iglesias, Rafaela Vaca, Olga Mínguez, Dolores Martínez, Maria Aguilà, Lydia Pascual, María Isabel Asensio, Esther de Benito, Carlos Carrera, María José García, María Teresa López, Ana Belén Cascajo, Beatriz Pascual, María Sara Narváez, Laura Cànaves, Nuria Gayà, Mónica de la Peña, Paloma Giménez, Susana García, Maria Concepción Piñas, Jorge Julián Monroy, Lucía Gorreto, Cecilia Carina Amato, Lorenzo González, Miguel Román, Marina Mainzer, María Elena Terrón, Teresa Díaz, Juan José Ruiz, Marta Cabello, Selene Cuevas, Susana Pérez, Laura García, Olga Cantalejo, María Belén Pedraja, Belén Ricalde, Mikel Azpiazu, Sara Pueyo, Almudena Fernández, Mercedes Hernández, Leire Luengo, Jorge Ullate, Maria Viviana Muñoz, Jesus Iturralde, Margarita Pinel, Anais Cruz, Saioa Escamilla, Carlos Ruiz-Martinez, Jose Alfonso Jiménez, Fernando Gallo, Rubén Esteban, Antonio Puente, Laura Pérez-Bozalongo, Paula Vicente, Jorge Lázaro, Marta Cristeto.

A list of the researchers participating in the Spanish Sleep Network is provided in the Appendix 1.