Acute pancreatitis is a potentially life-threatening condition with significant rates of morbidity, mortality, and recurrence.1 Its most common etiologies include gallstones and alcohol use, followed by hyperlipidemia.1 Although rare, acute pancreatitis can lead to neurological complications such as pancreatic encephalopathy and Wernicke's encephalopathy (WE).1

WE is a medical emergency caused by thiamine (vitamin B1) deficiency and is potentially reversible if intravenous thiamine is administered promptly.2 Its prevalence ranges from 0.4% to 2.8%.3–7 Without timely treatment, WE may progress to seizures, Korsakoff syndrome—which typically arises as ocular and encephalopathic symptoms resolve8—and even death.2

Chronic alcoholism is the most common underlying condition, accounting for approximately half of all WE cases.4,8 However, non-alcoholic WE is increasingly recognized and may be underdiagnosed. It has been associated with diverse clinical contexts, including hyperemesis gravidarum, malignancy, gastrointestinal surgeries (e.g., bariatric procedures), renal replacement therapies, prolonged parenteral nutrition, refeeding after starvation, anorexia nervosa, strict dieting, and HIV/AIDS.8 In predisposed patients, WE may be precipitated by intravenous glucose or carbohydrate loading.1,8

Compared to alcoholic WE, non-alcoholic cases may exhibit distinct clinical and radiological features, further complicating diagnosis.7 Mortality can reach 20%, underscoring the need for early recognition and intervention, particularly in atypical presentations.7 Rarely, hyperthyroid states such as Graves' disease can also precipitate thiamine deficiency and subsequent WE.9

Herein, we report the case of a middle-aged, non-alcoholic woman from rural India who developed WE secondary to recurrent vomiting following acute severe pancreatitis. Brain MRI revealed characteristic findings, and prompt administration of intravenous thiamine led to substantial neurological recovery. This case illustrates the diagnostic and therapeutic challenges of WE in non-alcoholic patients with gastrointestinal comorbidities.

A 45-year-old woman from rural India was admitted to our hospital in a confused state. Her initial presenting symptoms included severe epigastric abdominal pain accompanied by altered sensorium, which had evolved over the prior 24 h. On further inquiry, she reported a 14-day history of persistent vomiting and abdominal pain, for which she had been hospitalized elsewhere and diagnosed with acute severe pancreatitis. During that admission, her condition progressively worsened with the onset of confusion, blurred vision, vertigo over five days, and finally, drowsiness with marked disorientation.

She had no prior history of diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension, alcohol or illicit drug use, psychiatric illness, or family history of metabolic or neurodegenerative disease.

On examination, the patient was comatose, with a Glasgow Coma Scale score of E2V3M3. She was dehydrated, with hypotension (blood pressure 94/70 mmHg), a pulse rate of 96 bpm, a respiratory rate of 16/min, and a temperature of 36.9 °C. Abdominal examination revealed epigastric tenderness without signs of peritonitis.

Initial laboratory investigations showed hemoglobin 7.8 g/dL, mean corpuscular volume 104 fL, white blood cell count 12,900/μL, alanine aminotransferase 38 IU/L, triglycerides 250 mg/dL, serum albumin 3.1 g/dL, urea 28 mg/dL, sodium 134 mEq/L, and random blood glucose 128 mg/dL. Serum amylase and lipase were markedly elevated (597 IU/L and 647 IU/L, respectively). Thiamine levels were significantly reduced at 1.2 mcg/dL.

Cerebrospinal fluid analysis was unremarkable, with a clear and colorless fluid, three cells/μL, protein 30 mg/dL, glucose 67 mg/dL, and negative cultures and IgM results for scrub typhus and Japanese encephalitis virus.

Abdominal ultrasonography and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography ruled out the presence of gallstones and biliary obstruction. The pancreas appeared bulky and inflamed, consistent with ongoing pancreatitis, while liver echotexture and biliary anatomy were normal.

Neurologically, the patient was disoriented with global hyporeflexia, bilateral extensor plantar responses, and ophthalmoparesis characterized by bilateral lateral gaze palsy and both vertical and horizontal nystagmus.

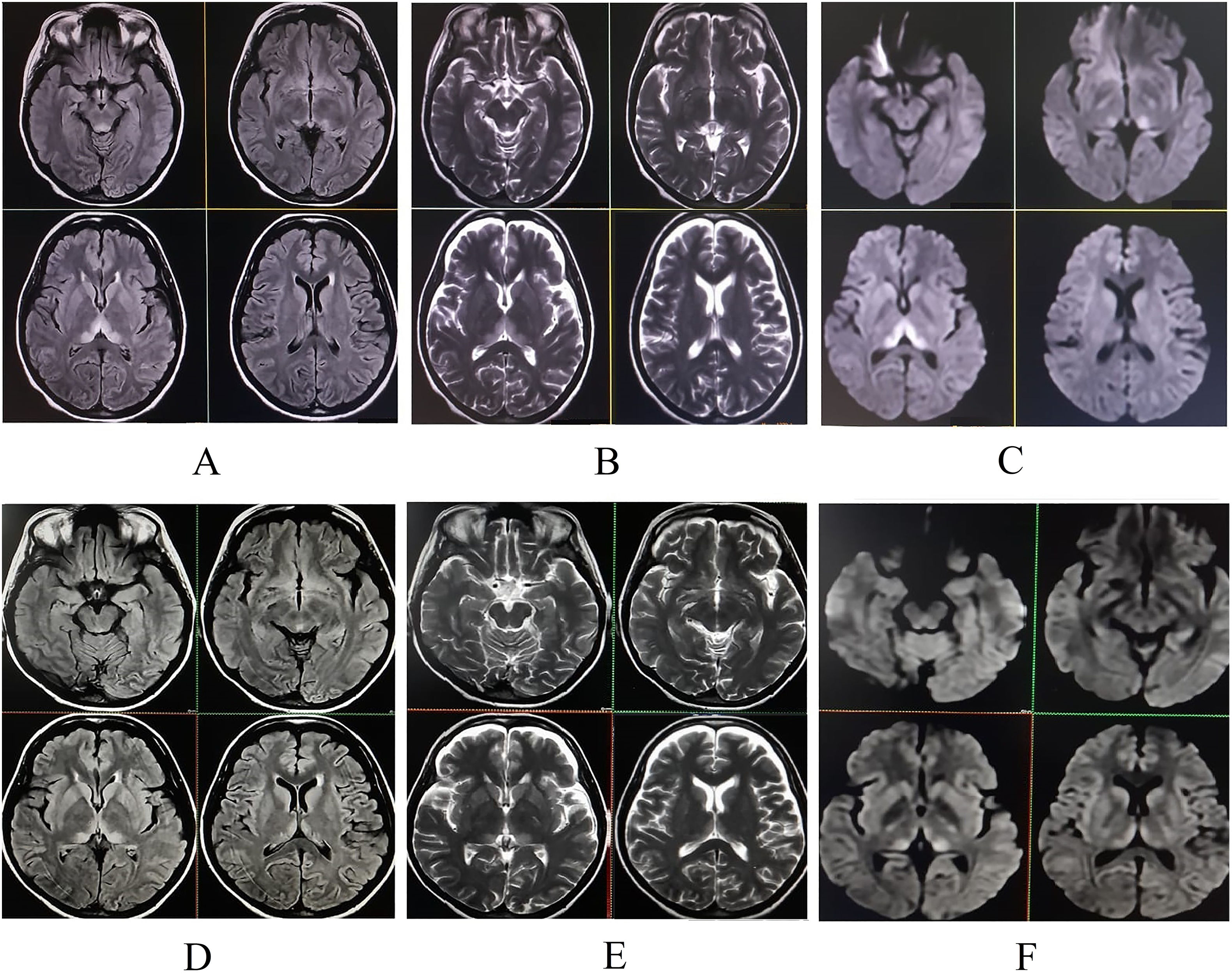

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain revealed symmetric hyperintensities in the thalami, hypothalamus, periaqueductal gray matter, and floor of the fourth ventricle on T2-FLAIR, T2-weighted, and diffusion-weighted sequences—findings typical of WE. Additionally, a focal hyperintensity was noted in the right superior frontal gyrus (Fig. 2), suggestive of cortical involvement—a feature more commonly associated with non-alcohol-related WE.11

A diagnosis of non-alcoholic WE secondary to thiamine depletion from prolonged vomiting in acute pancreatitis was established. The patient was started on high-dose intravenous thiamine (500 mg three times daily for two days), followed by 500 mg once daily for seven additional days. Marked clinical improvement was observed during hospitalization, with gradual recovery of consciousness and resolution of ocular motor abnormalities.

She was discharged in a hemodynamically stable condition with a prescription for oral thiamine 300 mg daily. At her two-week follow-up, she had fully recovered, with no residual neurological deficits. Repeat brain MRI showed resolving changes with hyperintensity in the right superior frontal gyrus on T2-weighted images (Fig. 1).

Upper panel (pre-treatment): Initial MRI of the brain. T2-FLAIR (A), T2-weighted (B), and diffusion-weighted imaging (C) sequences demonstrate hyperintensities in the periaqueductal region, mesencephalic tectum, hypothalamus, and paraventricular and medial thalami, consistent with Wernicke's encephalopathy.

Lower panel (post-treatment, two-week follow-up): Corresponding T2-FLAIR (D), T2-weighted (E), and diffusion-weighted imaging (F) sequences show significant resolution of the previously noted lesions following thiamine therapy.

WE is a potentially reversible but frequently underdiagnosed neurological emergency caused by thiamine (vitamin B1) deficiency. Thiamine is an essential cofactor in the Krebs cycle and pentose phosphate pathway; its depletion leads to impaired cerebral energy metabolism and subsequent cytotoxic and vasogenic edema.5 With total body thiamine reserves limited to 25–30 mg, deficiency can develop within weeks under conditions of poor intake, vomiting, or increased metabolic demand.10

The standard treatment of thiamine deficiency begins with parenteral administration—typically 100 mg/day IV in uncomplicated cases.11 In established WE, however, much higher doses are required: 500 mg IV three times daily for two days, followed by 500 mg IV once daily for at least five more days.10 Maintenance includes oral thiamine and correction of nutritional deficiencies.

Neuroimaging is pivotal in the diagnosis of WE. The classic MRI pattern includes symmetric T2-FLAIR hyperintensities in the medial thalami, hypothalamus, mammillary bodies, and periaqueductal gray.2,6 In non-alcoholic patients, atypical involvement of the cerebellum, cranial nerve nuclei, and cerebral cortex has been described.2,9 Some authors propose that alcohol might exert a neuroprotective effect in regions typically spared in alcoholic WE, potentially explaining these radiological differences.7 That said, typical findings can still be present in non-alcoholic WE, as seen in our case.12

Importantly, several other radiological differentials must be considered when bilateral thalamic involvement with diffusion restriction is observed, as this pattern is not pathognomonic for WE. For instance, posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES)—though classically affecting the parieto-occipital lobes—can occasionally involve the thalami, especially in atypical forms.13 Ghosh et al.13 described a patient with PRES triggered by hypercalcemia due to undiagnosed primary hyperparathyroidism, presenting with seizures and acute pancreatitis. Similarly, acute intermittent porphyria can lead to multifocal brain involvement, including the thalami, in the context of acute neurovisceral crises. Another differential diagnosis is autoimmune encephalitis—particularly anti-NMDAR encephalitis—which may exhibit diffuse or limbic system hyperintensities and can clinically mimic WE.14 However, cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis, autoantibody positivity, and a subacute behavioral syndrome often guide the diagnosis.14 In all such cases, correlating the radiological findings with clinical presentation and targeted laboratory testing is essential to reach an accurate diagnosis.

Although uncommon, both pancreatic encephalopathy and WE have been reported as complications of acute pancreatitis. The former tends to appear early in the disease course, while WE usually emerges later, often precipitated by persistent vomiting, malnutrition, and catabolic stress.2 The exact mechanisms linking pancreatitis and WE remain incompletely understood, but thiamine depletion in the context of systemic inflammation and nutritional compromise is a plausible pathway.

Our patient presented with severe abdominal pain and altered sensorium, prompting a broad differential diagnosis, including diabetic ketoacidosis, hypercalcemia, adrenal insufficiency, acute intermittent porphyria, PRES, and autoimmune encephalitis. Systematic clinical and laboratory evaluation, however, ruled out these possibilities. Notably, the patient had low serum thiamine, typical MRI findings, and rapid clinical improvement following high-dose IV thiamine, all of which supported a definitive diagnosis of non-alcoholic WE.

To our knowledge, this is the second reported case of non-alcoholic WE associated with acute pancreatitis that presented in a coma and achieved full recovery.15 As in the prior report, early diagnosis and prompt parenteral thiamine administration were key in preventing irreversible neurological damage.

This case underscores the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for WE in non-alcoholic patients with pancreatitis, especially those with prolonged vomiting or poor oral intake. Recognition of MRI patterns—particularly symmetric thalamic hyperintensities—should prompt urgent empiric treatment while keeping in mind important radiologic differentials. Clinician awareness and early intervention remain critical to improving outcomes in this potentially fatal but reversible condition.

Author contributionsAll authors contributed significantly to the creation of this manuscript; each fulfilled the criteria as established by the ICMJE.

Study fundingNil.

DisclosuresNone of the authors reports any relevant disclosures.

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.