Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (aHSA) is a neurological emergency with high morbidity and mortality. Its timely management is crucial to improve the prognosis. This review analyzes diagnostic and therapeutic advances, with emphasis on the comparison between endovascular and surgical approaches, highlighting their impact on the clinical evolution of patients.

MethodsThis article is a narrative review. An exhaustive literature search on aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage was made in scientific databases: PUBMED, EMBASE, LILACS and TripDatabase, and articles referring to the diagnosis and treatment of this pathology.

ResultsTo get to know the updates and scientific advances in the early diagnosis and timely treatment of aaHSA, whether endovascular or microsurgical, should be the goal of the treating group of patients who suffer from it. The continuous evolution in medical and interventional therapeutic measures, aimed at their initial management and their complications, corresponds to the need to seek alternatives to improve vital and functional outcomes for patients. New interventions could be implemented as treatment standards in the coming years, for example, the use of lumbar drainage systems of cerebrospinal fluid or new therapies for the prevention and management of late cerebral ischemia.

ConclusionsThe management of this pathology is a therapeutic challenge and requires a multidisciplinary approach. Recent therapeutic advances have expanded the available options, improving the prognosis and functionality of patients.

La hemorragia subaracnoidea aneurismática (aHSA) es una emergencia neurológica con alta morbilidad y mortalidad. Su manejo oportuno es crucial para mejorar el pronóstico. Esta revisión analiza avances en el diagnóstico y tratamiento, con énfasis en la comparación entre enfoques endovasculares y quirúrgicos, destacando su impacto en la evolución clínica de los pacientes.

MétodosEste artículo es una revisión narrativa. Se realizó una búsqueda exhaustiva en bases de datos científicas (PUBMED, EMBASE, LILACS y TripDatabase) sobre la hemorragia subaracnoidea aneurismática, incluyendo artículos relacionados con el diagnóstico y tratamiento de esta patología.

ResultadosConocer las actualizaciones y avances científicos en el diagnóstico precoz y el tratamiento oportuno, ya sea endovascular o microquirúrgico, debe ser el objetivo del equipo que atiende a los pacientes afectados. La continua evolución en las medidas terapéuticas médicas e intervencionistas, dirigidas a su manejo inicial y a las complicaciones, refleja la necesidad de buscar alternativas para mejorar los resultados vitales y funcionales de los pacientes. En los próximos años, podrían implementarse nuevas intervenciones como estándares de tratamiento, por ejemplo, el uso de sistemas de drenaje lumbar de líquido cefalorraquídeo o nuevas terapias para la prevención y manejo de la isquemia cerebral tardía.

ConclusionesEl manejo de esta patología representa un desafío terapéutico y requiere un enfoque multidisciplinario. Los avances terapéuticos recientes han ampliado las opciones disponibles, mejorando el pronóstico y la funcionalidad de los pacientes.

Cerebrovascular disease (CVD) is the third leading cause of natural death worldwide, according to data from the World Health Organization (WHO), with hemorrhagic stroke accounting for 10–27% of all cases.1

Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (aSAH) represents 15–20% of hemorrhagic strokes; however, it is highly lethal, contributing to approximately 50% of all CVD-related deaths.2,3 Its global incidence is approximately 6.1 per 100,000 person-years, with a global prevalence of 8.09 million cases and pre-hospital mortality rates ranging between 22% and 26%.4 In Colombia, a mortality rate of 3.9 per 100,000 people per year has been reported, with 60.4% of cases occurring in women and 39.6% in men.5

This article aims to synthesize the latest evidence and recommendations regarding both the diagnosis and treatment of this condition, with an emphasis on endovascular and surgical approaches. It highlights their impact on clinical outcomes, offering a comprehensive framework for the timely management of this pathology.

PathophysiologyaSAH involves multiple disruptions in the homeostasis of the central nervous system, such as the loss of cerebral autoregulation, accumulation of blood in the subarachnoid space, and delayed cerebral ischemia. However, it all begins with the formation of the aneurysm itself and its inherent risk of rupture.6

Hemodynamic stress at arterial bifurcations causes endothelial damage, activating the NF-kB pathway, which triggers inflammation, macrophage recruitment, and weakening of cellular junctions. Additionally, excessive destruction of the extracellular matrix, mediated by matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-2 and MMP-9), further compromises the vascular wall.7 After rupture, blood accumulates in the subarachnoid space, disrupting membrane channels responsible for intrinsic myogenic activity and promoting vasoconstriction, which may lead to hypoxic–ischemic injury.8

Clinical manifestationsAneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (aSAH) presents a broad spectrum of clinical manifestations, ranging from headache to altered levels of consciousness. Aneurysmal rupture commonly manifests as a thunderclap headache, which is defined as a sudden-onset, severe-intensity headache that reaches its peak within less than one minute and persists for more than five minutes.9 During a systems review, sentinel headache may be reported—this is a sudden-onset, intense but self-limiting headache that occurs days or weeks prior to aneurysm rupture.

Neurological examination may reveal signs of meningeal irritation such as Kernig's and Brudzinski's signs, Jolt accentuation, or pain upon ocular pressure.6 In some cases, Terson's syndrome may be observed, consisting of subhyaloid, vitreous, or retinal hemorrhages associated with intracranial bleeding. This finding is indicative of elevated intracranial pressure and is associated with a worse prognosis.10 Additional physical findings depend on the size and location of the aneurysm. To objectively classify patients, clinical grading scales have been implemented, as outlined below.

Clinical grading scalesScoring scales are useful tools to estimate neurological prognosis and mortality in aSAH. Their use aids in guiding therapeutic decisions and provides statistical support for identifying patients with devastating neurological injury and a poor likelihood of recovery.

The strongest predictors of mortality and poor outcomes, supported by statistical evidence, include advanced age, lower level of consciousness on admission, and the volume of hemorrhage estimated through imaging.

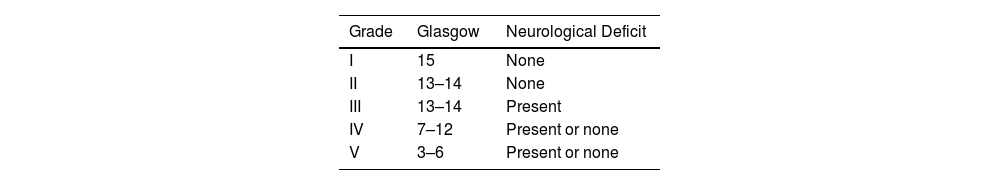

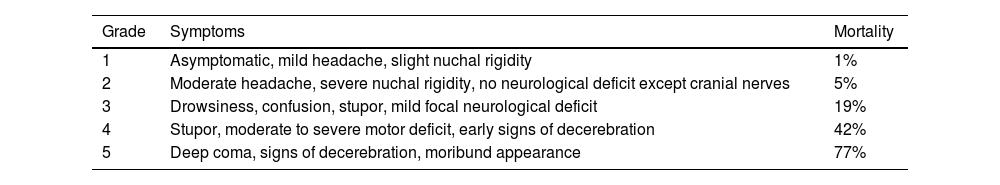

The World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies (WFNS) scale for aSAH combines elements of the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) and motor deficits.11 (Table 1). The Hunt and Hess (H&H) scale, proposed in 1968, categorizes patients into grades 1 through 5, with increasing levels of expected mortality. Grade 1 is associated with minimal mortality, while grade 5 is linked to the highest mortality rate.11 (Table 2).

Hunt and Hess.

| Grade | Symptoms | Mortality |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Asymptomatic, mild headache, slight nuchal rigidity | 1% |

| 2 | Moderate headache, severe nuchal rigidity, no neurological deficit except cranial nerves | 5% |

| 3 | Drowsiness, confusion, stupor, mild focal neurological deficit | 19% |

| 4 | Stupor, moderate to severe motor deficit, early signs of decerebration | 42% |

| 5 | Deep coma, signs of decerebration, moribund appearance | 77% |

The WFNS scale demonstrates a sensitivity (S) of 91%, specificity (Sp) of 71%, positive predictive value (PPV) of 65%, and negative predictive value (NPV) of 93% in predicting mortality from aSAH. In contrast, the H&H scale shows a sensitivity of 57%, specificity of 83%, PPV of 67%, and NPV of 76% for this outcome at 30 days post-hemorrhage.11

Aneurysm treatment is preferred in patients with good clinical status—i.e., those graded 1–3 on the H&H scale. Patients with high-grade aSAH may still be considered for aneurysm treatment, especially if they do not have a devastating and irreversible neurological injury.

NeuroimagingThe appropriate selection of imaging modalities is essential to ensure timely diagnosis of aSAH. It is crucial to choose accessible yet effective methods for proper evaluation.

Non-contrast cranial Computed Tomography (CT)This is the most commonly used technique in emergency settings when aSAH is suspected. It offers advantages such as rapid acquisition time and broad availability across various levels of medical care. It has a sensitivity of approximately 94.7% and specificity of 98.3% during the initial hours after the event. This technique is considered the gold standard due to its cost-effectiveness compared to other imaging modalities.12

However, CT effectiveness depends on the time elapsed since symptom onset. Its diagnostic performance is optimal within the first 6 h following the hemorrhagic event, during which its sensitivity and specificity are highest. Beyond this window, its accuracy significantly decreases. Furthermore, diagnostic precision relies heavily on the expertise of the interpreting physician. Under ideal conditions, a properly interpreted negative CT scan has a post-test probability of aSAH of less than 0.15%, reaching a negative predictive value (NPV) of 99.9% if performed within 6 h and read by a trained radiologist.12 Therefore, whenever possible, interpretation should be performed by experienced personnel.

CT Angiography (CTA)CTA is the second most commonly used modality and offers the advantage of providing an etiological diagnosis along with anatomical information, which is critical for surgical planning. In specialized centers, it has become the preferred initial method, with sensitivity and specificity nearing 97%. However, it has limitations in detecting aneurysms smaller than 3 mm, where sensitivity drops to 61%.13 Additionally, its use is limited in some contexts due to higher costs compared to other techniques.

Magnetic Resonance Angiography (MRA)Though less widely available, MRA can be valuable when accessible. Its utility in routine practice is reduced due to high costs, limited availability, longer acquisition times, and susceptibility to motion artifacts in critically ill patients. Furthermore, its sensitivity for detecting aneurysms smaller than 5 mm is lower compared to CTA and digital subtraction angiography (DSA).14 Currently, its use is reserved for specific cases, such as in pregnant patients where radiation exposure must be minimized, or in patients unable to receive contrast agents, using time-of-flight (TOF) sequences.

Digital Subtraction Angiography (DSA)DSA remains the gold standard for etiological diagnosis and surgical planning, as it allows for highly detailed visualization of vascular anatomy. It can detect aneurysms not visible with other methods, such as blister-type aneurysms or those smaller than 3 mm.15 It has a sensitivity of 87.7% and specificity of 95.8% for aSAH diagnosis. However, its use has declined due to the risks associated with its invasive nature, limiting its application to specific situations in highly specialized centers.14,15

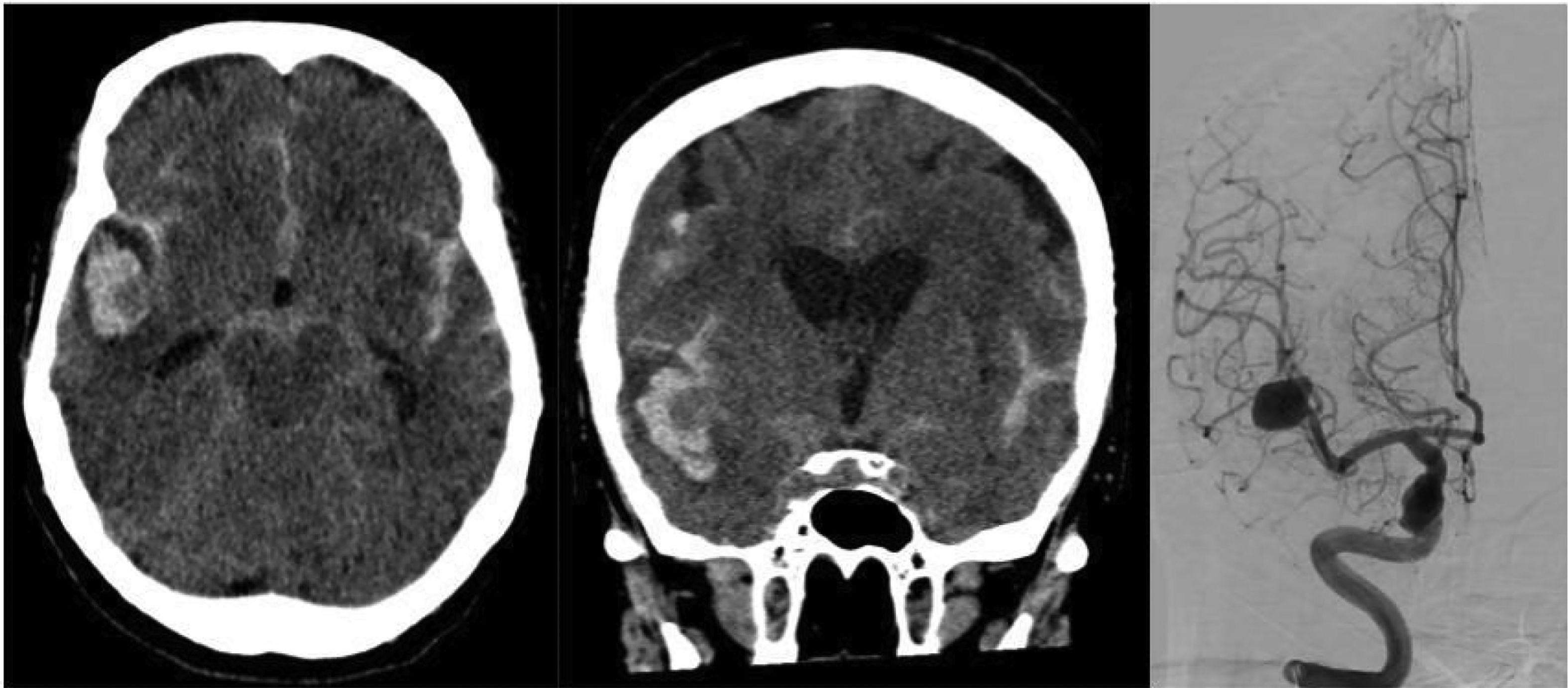

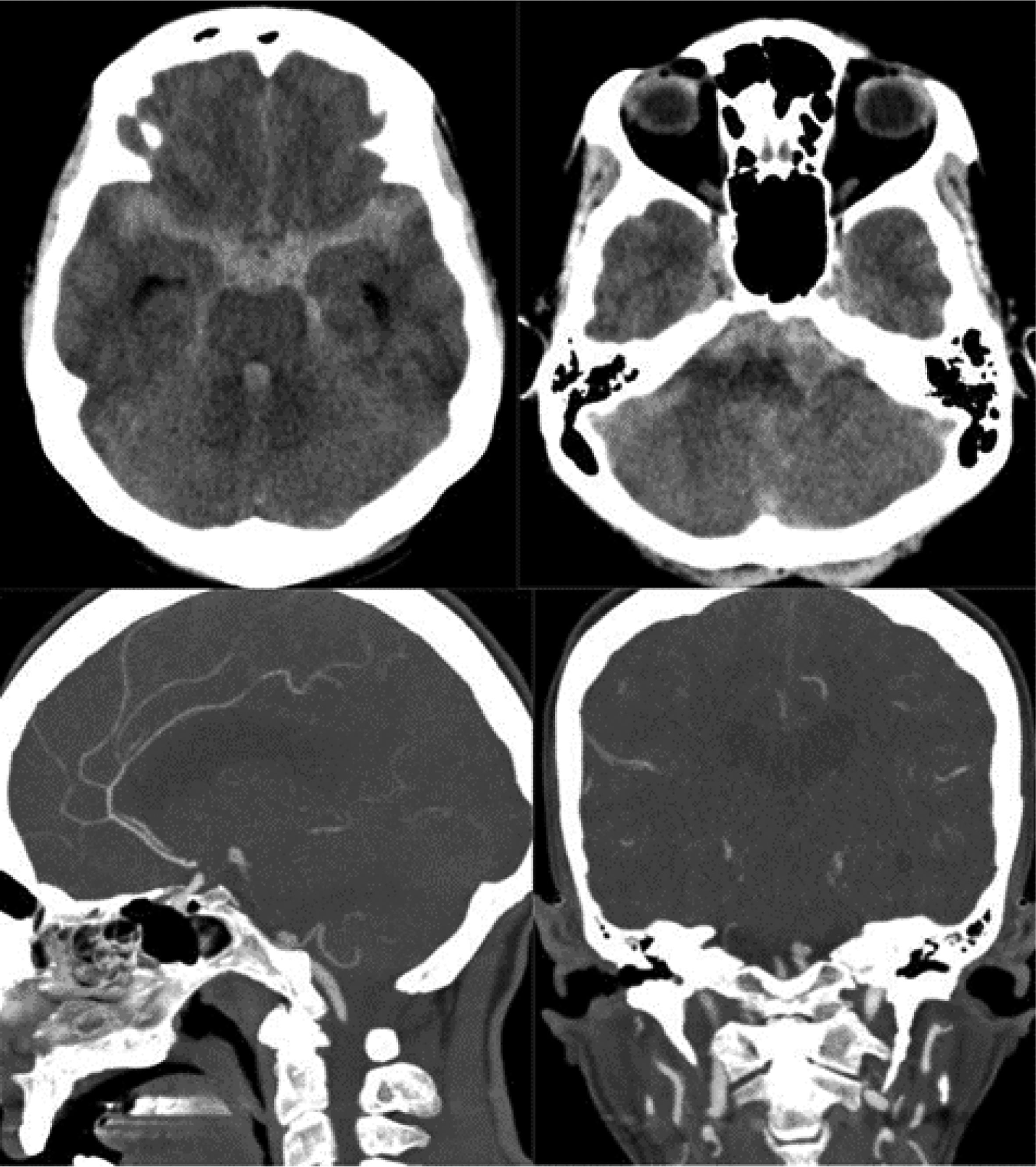

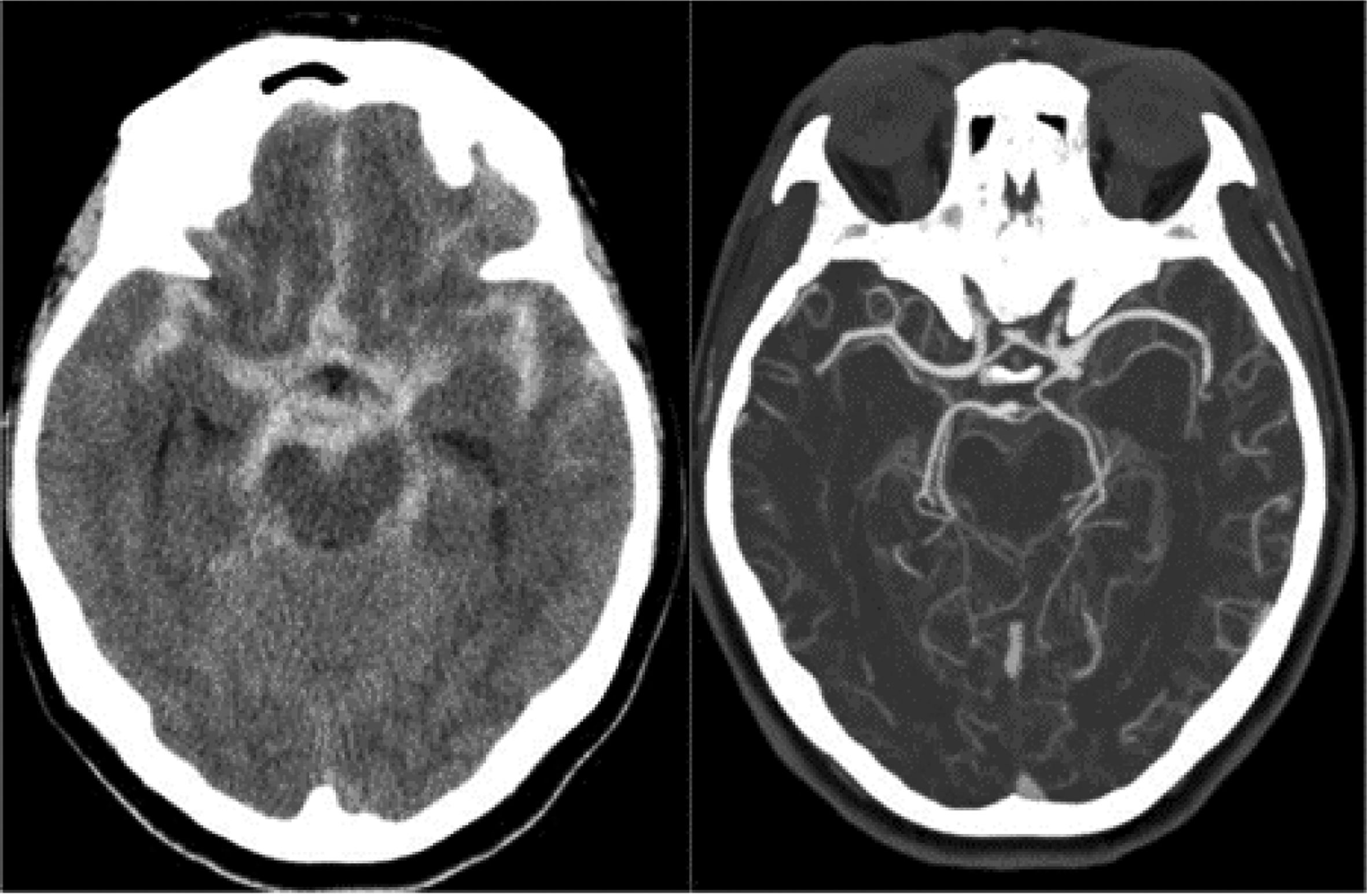

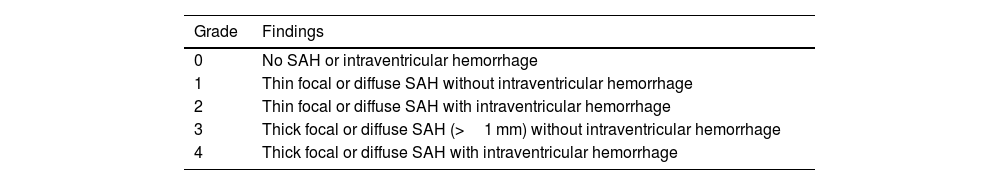

There are imaging scales, such as the modified Fisher scale, used to assess the degree of hemorrhage and guide treatment. This scale is divided into five grades based on the extent of bleeding, involvement of cisterns, and intraventricular hemorrhage. It helps predict the likelihood of vasospasm in patients—the higher the grade, the worse the prognosis.15 (Table 3 and Figs. 1–3).

Modified fisher scale.

| Grade | Findings |

|---|---|

| 0 | No SAH or intraventricular hemorrhage |

| 1 | Thin focal or diffuse SAH without intraventricular hemorrhage |

| 2 | Thin focal or diffuse SAH with intraventricular hemorrhage |

| 3 | Thick focal or diffuse SAH (>1 mm) without intraventricular hemorrhage |

| 4 | Thick focal or diffuse SAH with intraventricular hemorrhage |

Non-contrast axial CT scan (axial and sagittal views) showing subarachnoid hemorrhage predominantly in the right Sylvian fissure, Fisher grade 3. Cerebral panangiography in anteroposterior (AP) projection reveals a giant saccular aneurysm at the bifurcation of the right middle cerebral artery (MCA).

Lumbar puncture (LP) has specific indications in the evaluation of aSAH and is recommended when there is high clinical suspicion despite a negative CT scan.16 Xanthochromia is a typical finding, along with elevated protein levels, red blood cells, and leukocytes in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).16,17 Serial collection in three tubes helps differentiate between a traumatic tap and true xanthochromia.17 Paraclinical tests for early detection of coronary complications associated with aSAH are part of standard management in some care centers.

TreatmentSurvival and quality of life in patients who have suffered aSAH largely depend on receiving comprehensive, optimal, and timely treatment. Each step in management must be carried out with great care and rigor—from non-pharmacological and pharmacological medical care to definitive therapies, whether endovascular or surgical, and individualized neurological rehabilitation thereafter. Ideally, management should begin as soon as possible and be completed within 24 h of the hemorrhagic event.18 Given the wide range of current therapeutic options, it is essential to understand their advantages, disadvantages, and appropriate indications. The following provides an overview of the key treatment steps and options.

Pharmacological and non-pharmacological medical therapyaSAH typically presents abruptly and, in most cases, unexpectedly. For those patients who survive the initial minutes after the hemorrhagic event, primary medical care is crucial to improving survival and rehabilitation outcomes.19 Early medical management paves the way for definitive therapies and should therefore be well understood in routine clinical practice, even in institutions without access to specialties such as neurointervention or neurosurgery.

Primary medical interventions are primarily aimed at stabilizing the patient's vital signs and, in the context of aSAH, preventing complications such as rebleeding, hydrocephalus, delayed cerebral ischemia, electrolyte imbalance, venous thromboembolism, seizures, and ensuring adequate cerebral oxygenation.20

Once a clinical presentation suggestive of aSAH is identified, the physician must initiate a series of measures to mitigate the risk of complications. First, the patient's vital signs should be assessed, ensuring a patent airway, proper ventilation, and circulation.21 It is important to note that advanced resuscitation and intensive care procedures involve risk and should only be performed in patients who are candidates for such interventions and/or have not previously expressed refusal through appropriate legal means.22

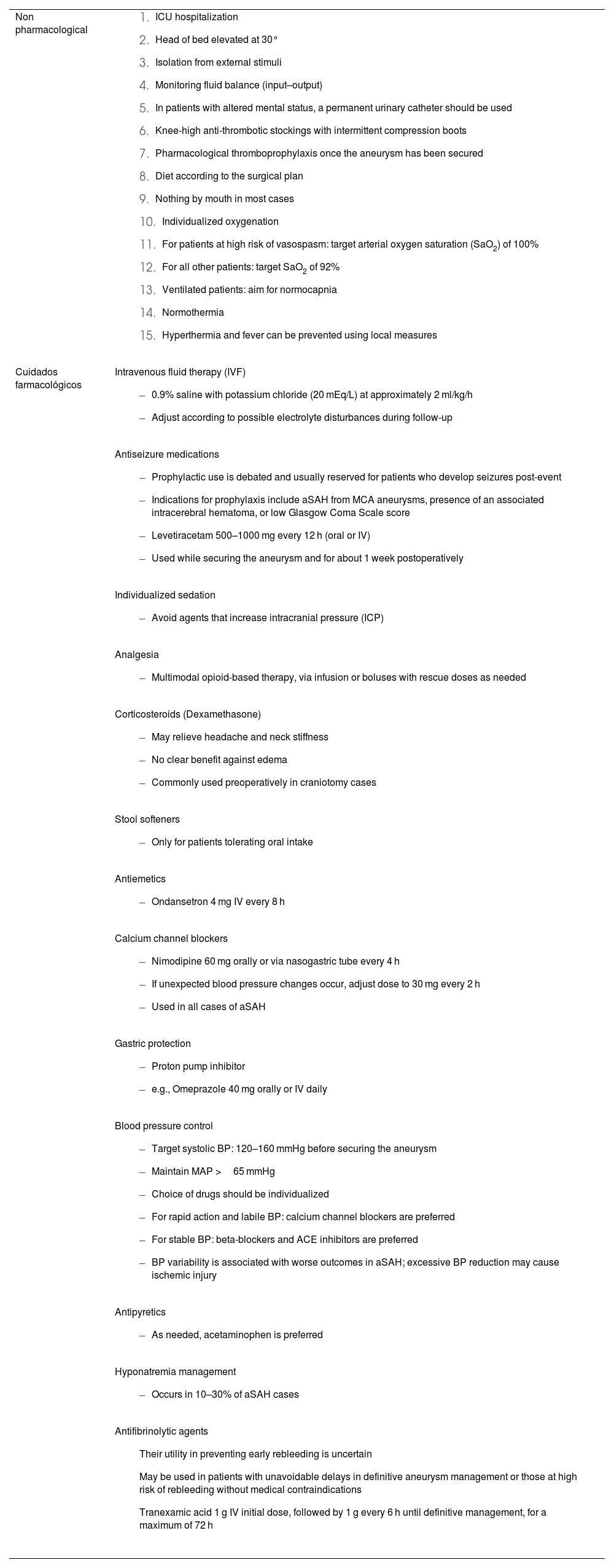

Following initial stabilization of the patient with aSAH, continuous monitoring should be instituted in an intensive care unit (ICU), preferably in a specialized neurocritical care unit.23 The following table summarizes the key supportive care measures that must be ensured for these patients.24 (Table 4).

| Non pharmacological |

|

| Cuidados farmacológicos | Intravenous fluid therapy (IVF)

|

Antiseizure medications

| |

Individualized sedation

| |

Analgesia

| |

Corticosteroids (Dexamethasone)

| |

Stool softeners

| |

Antiemetics

| |

Calcium channel blockers

| |

Gastric protection

| |

Blood pressure control

| |

Antipyretics

| |

Hyponatremia management

| |

Antifibrinolytic agents

|

The definitive treatment of aSAH through complete exclusion of the aneurysm significantly reduces the risk of rebleeding. Even in patients where full exclusion is not immediately possible, partial management with the aim of achieving stabilization and planning a second intervention has been shown to improve morbidity and mortality outcomes.25,26

Endovascular therapy: Techniques, indications, and clinical trialsIn recent years, endovascular therapy has gained significant ground in the management of patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. It is an emerging and versatile method that, when combined with panangiography, serves both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes.27 Among the available options are coils, stents, flow diverters, and combined techniques, allowing for effective management tailored to the aneurysm's type, location, and morphology.28

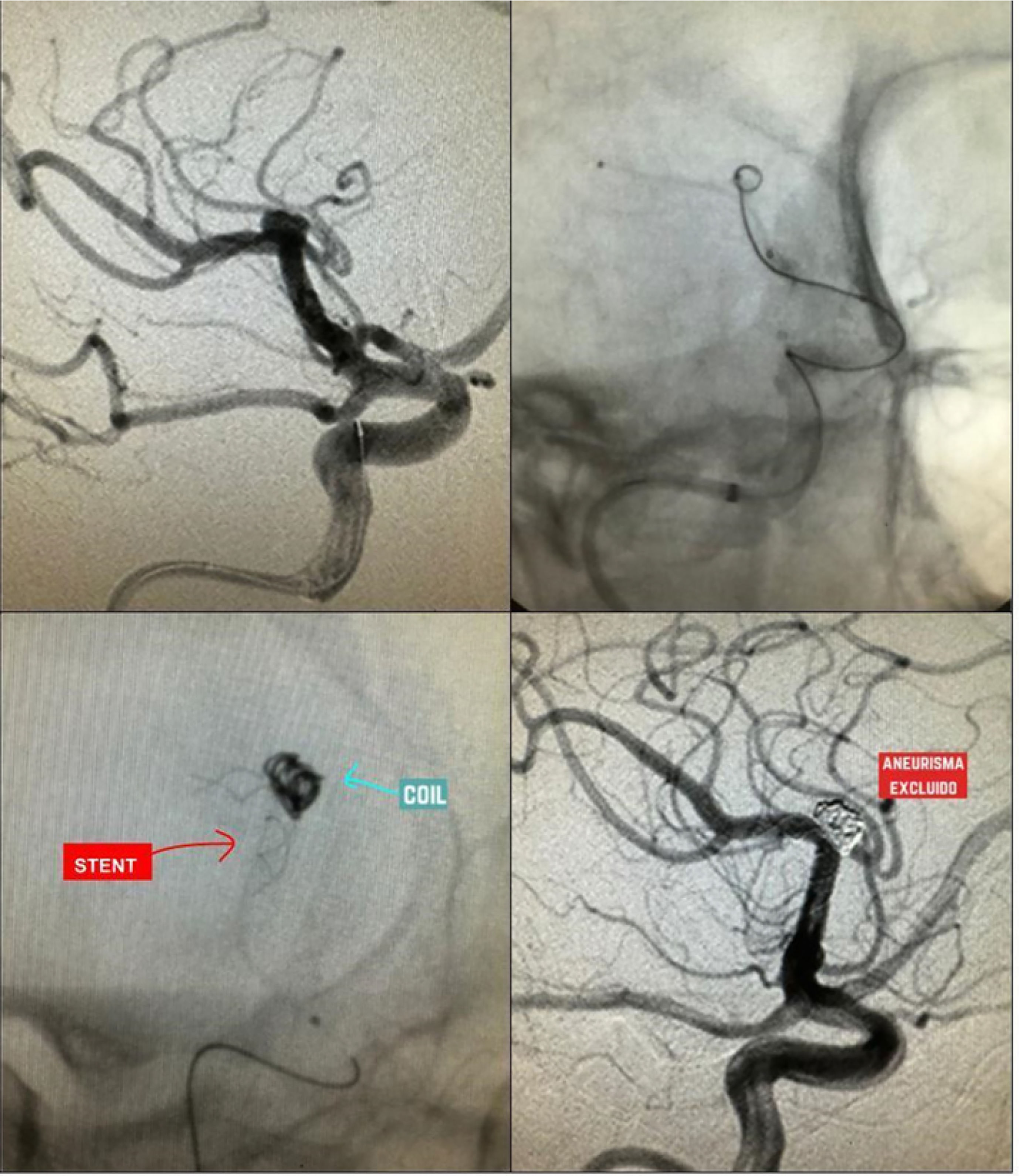

Simple coiling is the most frequently used treatment in the context of aSAH. This technique requires specifically shaped coils (e.g., basket, helical, wave) designed to adapt to the aneurysm's morphology in order to achieve a satisfactory packing density.28 The coil is inserted via a catheter and guided fluoroscopically to the site of the lesion. The material is then deployed in a basket-like fashion, from the periphery toward the center, until there is no evidence of contrast filling within the aneurysm.28,29 (Figs. 4–6).

Cerebral panangiography showing a saccular aneurysm in the communicating segment, treated with a mixed technique using coil plus stent (red arrow indicating the stent, and blue arrow showing the coil within the aneurysm). Follow-up imaging shows no flow within the aneurysm, indicating successful exclusion. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

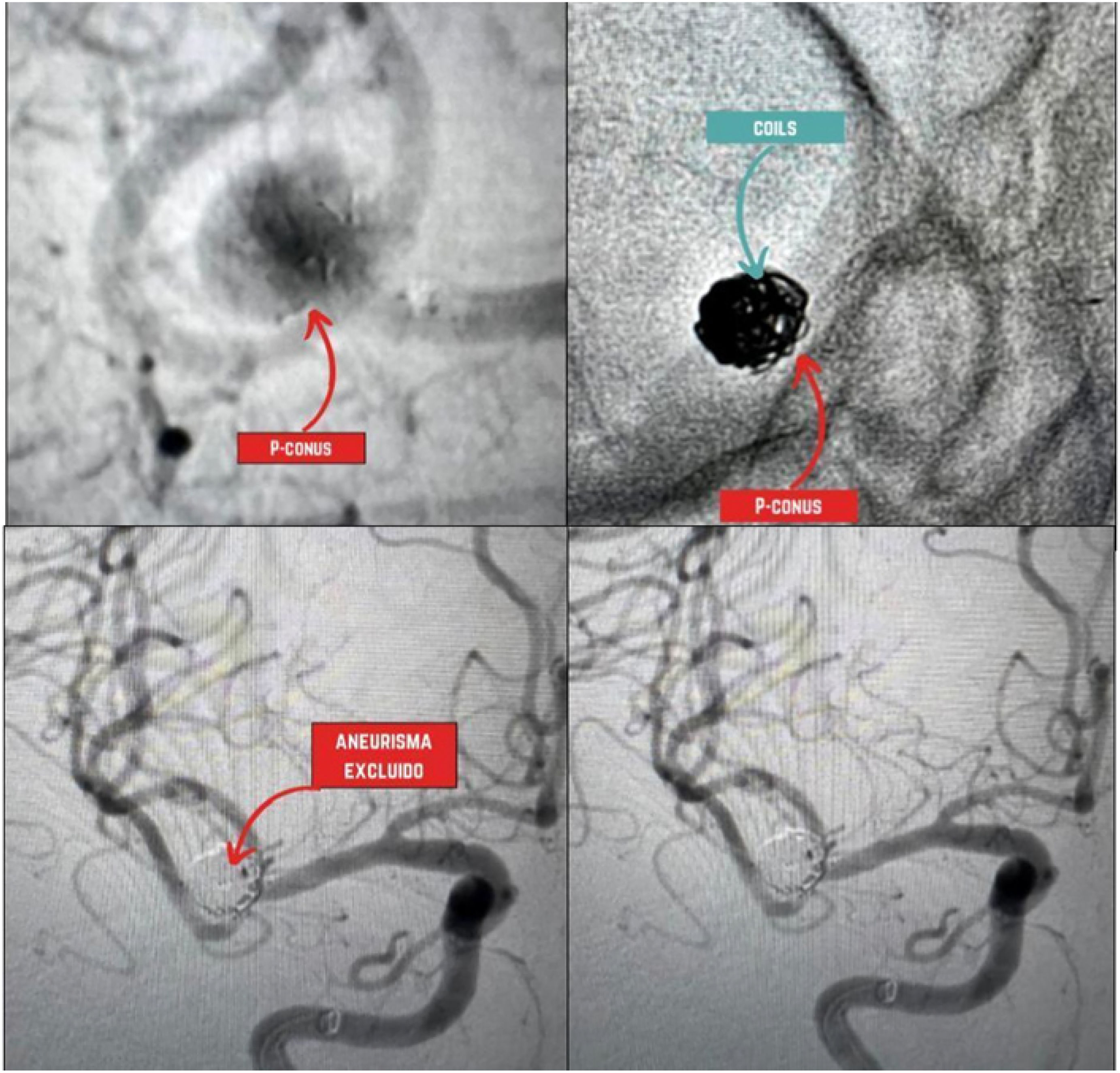

Cerebral panangiography showing a saccular aneurysm at the MCA bifurcation excluded using a P-conus device and coils (upper panel images, red arrow indicating the P-conus, and blue arrow showing the coils within the aneurysm). Follow-up acquisitions (lower panel images) demonstrate successful aneurysm exclusion. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

For wide-neck aneurysms, it is recommended to combine techniques such as coiling with stents or flow diverters. These devices help prevent coil protrusion, displacement, or migration, which could otherwise lead to occlusion or thromboembolic events.30 These devices are also used in fusiform aneurysms, blister-type aneurysms, or giant aneurysms located in the internal carotid artery.28,30

Other devices used in assisted coiling techniques include the p-CONUS, an intraluminal stent-like device with a specialized shape designed for the treatment of wide-neck aneurysms located at arterial bifurcations.31

Some of the complications associated with coiling include intraoperative aneurysm rupture, coil migration, or perforation.32 The CLARITY study describes various complications of coiling in patients with aSAH. In this cohort, 50.6% of patients had aneurysms located in the anterior communicating artery complex. The most commonly used technique was simple coiling, accounting for over 77% of cases. One notable complication was thromboembolic events, which occurred in 12.5% of patients, both intraoperatively and postoperatively. These events were significantly more frequent in smokers and in aneurysms larger than 10 mm or with necks wider than 4 mm.33 The thromboembolic risk in patients with ruptured aneurysms is up to four times higher than in those with unruptured aneurysms. Intraoperative rupture occurred in 4.4% of patients, most commonly in those with middle cerebral artery aneurysms.32,33

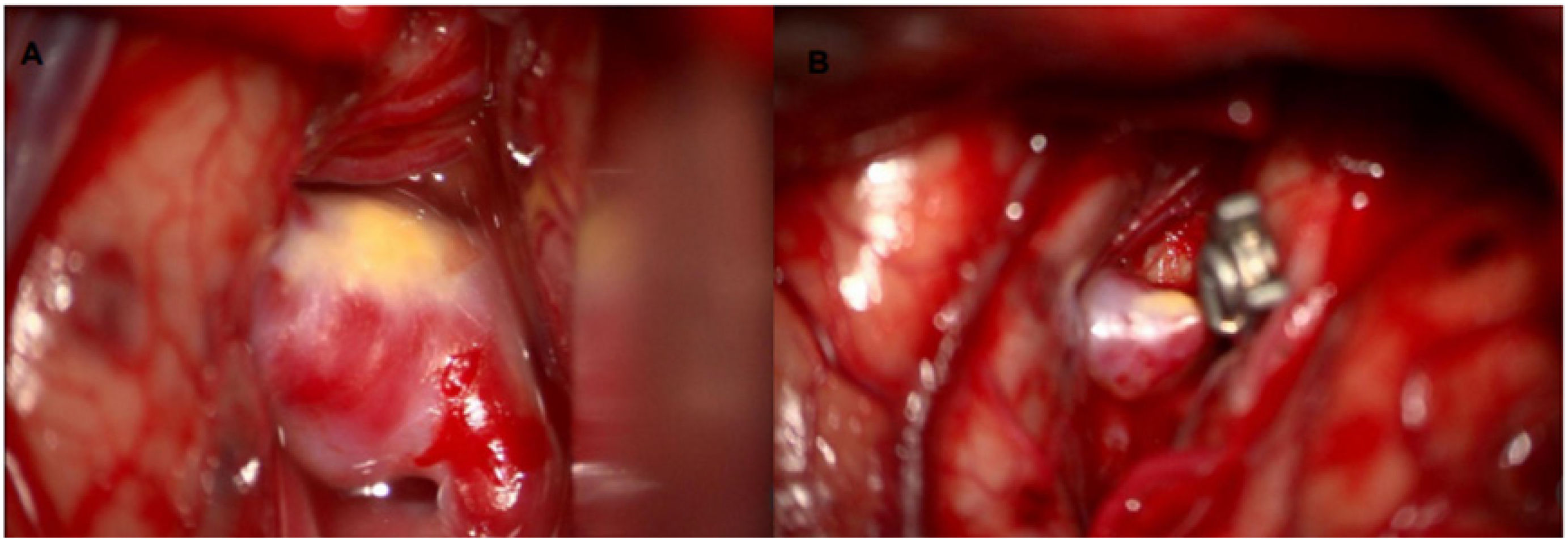

Surgical managementFavorable outcomes following surgical treatment of aneurysms are often linked to the surgeon's experience. Surgical clipping of an aneurysm is only likely to yield superior results compared to endovascular management if performed at a specialized center with a high patient volume (approximately more than 35 cases per year).34 (Fig. 7).

This procedure involves the surgical placement of a clip around the neck of the aneurysm, excluding it from the cerebral circulation without occluding the normal flow in adjacent vessels. Surgical coverage of the aneurysm using the patient's own tissues (e.g., muscle) or synthetic materials (e.g., resins, polymers, or Teflon) may be an alternative in cases where complete exclusion is not feasible—for example, when an important arterial branch arises from the aneurysm dome.35These complications must be anticipated so that the neurointerventionist can manage them effectively. For example, in the case of aneurysm rupture, immediate reversal of heparin with an infusion of 5–10 mg of protamine is recommended, along with evaluation for potential ventricular drainage device placement.34 In cases of coil migration leading to occlusion of other arterial territories, intra-arterial administration of antiplatelet agents can be used, and aspiration techniques may be employed if pharmacological management fails.28,32 For coil protrusion, thromboembolic risk is typically managed with antiplatelet therapy, and previously mentioned adjunctive techniques—such as stent-assisted coiling, flow diverters, or balloon-assisted coiling—may be applied.33

Surgical management may be preferred in patients with narrow-neck aneurysms located in the middle cerebral artery (MCA), in cases where an associated intracerebral hematoma is suitable for drainage, or when there is an accompanying subdural hematoma. It is also indicated when symptoms are caused by compression of adjacent structures by the aneurysm dome (e.g., third cranial nerve palsy in posterior communicating artery [PCoA] aneurysms), or in younger patients who have lower surgical risk and a reduced likelihood of aneurysm recurrence.36,37

There is strong evidence supporting early treatment. Some studies have shown worse outcomes when management is initiated during the peak risk window for vasospasm. However, more recent studies have challenged this belief, showing similar results in patients treated during the vasospasm peak compared to those treated later.37,38 Nevertheless, early intervention is widely accepted to improve the prognosis of definitive aneurysm treatment and overall patient outcomes.39,40

ISAT and BRAT studies (Endovascular therapy vs surgical clipping)Currently, two major studies—the International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) and the Barrow Ruptured Aneurysm Trial (BRAT)—compare conventional surgical management versus endovascular treatment for patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage.25,41

In the ISAT study, the safety profiles of patients eligible for both procedures were compared. At 12 months, the endovascular treatment group showed better clinical outcomes (23.7%) compared to the aneurysm clipping group (30.6%), based on a modified Rankin Scale score of <2.42

The BRAT study found that the endovascular coiling technique was associated with a lower rate of unfavorable clinical outcomes, and it also demonstrated a lower incidence of seizures in patients who underwent endovascular treatment compared to those who underwent surgical clipping. However, at the 10-year follow-up, functional outcomes were comparable between both groups. Patients who received endovascular therapy required a greater number of reinterventions for aneurysm management.43

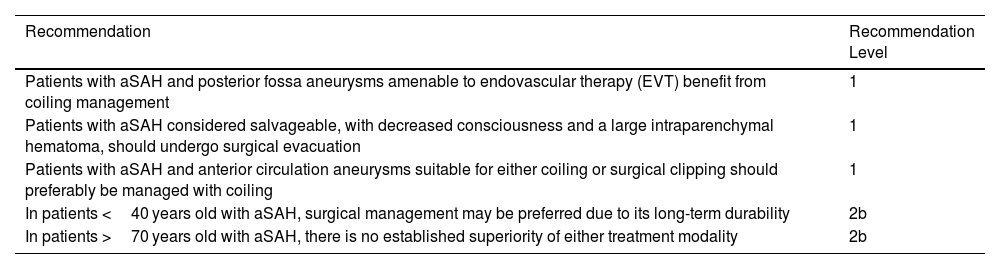

According to the latest clinical practice guidelines from the American Heart Association (AHA), in patients with ruptured posterior fossa aneurysms, an endovascular approach is preferred over surgical clipping due to easier access and favorable short- and long-term outcomes.25 In patients over 70 years old, no specific intervention is favored, as differences in this subgroup were not statistically significant.25 Nonetheless, treatment decisions should consider the experience of the treating center, and most importantly, the timeliness of the intervention to ensure patients are managed as early as possible.43 (Table 5).

2023 AHA recommendations for the treatment of ruptured cerebral aneurysms.25

| Recommendation | Recommendation Level |

|---|---|

| Patients with aSAH and posterior fossa aneurysms amenable to endovascular therapy (EVT) benefit from coiling management | 1 |

| Patients with aSAH considered salvageable, with decreased consciousness and a large intraparenchymal hematoma, should undergo surgical evacuation | 1 |

| Patients with aSAH and anterior circulation aneurysms suitable for either coiling or surgical clipping should preferably be managed with coiling | 1 |

| In patients <40 years old with aSAH, surgical management may be preferred due to its long-term durability | 2b |

| In patients >70 years old with aSAH, there is no established superiority of either treatment modality | 2b |

Inspired by Hoh et al., “2023 Guideline for the Management of Patients With Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: A Guideline From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association”.25

Delayed cerebral ischemia (DCI) is one of the main complications of subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) and a significant cause of morbidity among patients who survive the initial event. It most commonly presents between days 3 and 14 post-hemorrhage as a new focal neurological deficit or a drop of more than 2 points on the Glasgow Coma Scale, without any other identifiable cause. Its pathophysiology centers on three key mechanisms: vascular dysfunction, inflammation, and cortical spreading depolarization.44

Vascular dysfunction involves late-onset vasoconstriction, hypoperfusion, and microthrombosis phenomena. Inflammation is characterized by elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress. Finally, cortical spreading depolarization increases metabolic demand in the context of compromised perfusion, facilitating ischemia and cytotoxic injury.44

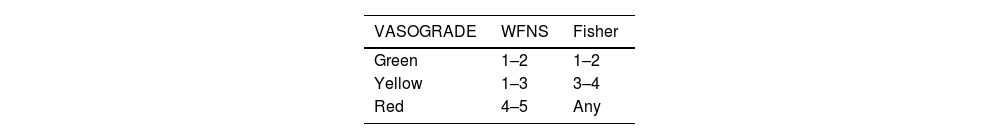

Clinical grading tools such as the VASOGRADE scale are used to stratify the risk of DCI into three levels: low (green), moderate (yellow), and high (red).45 (Table 6).

Neuromonitoring for vasospasm and DCITranscranial Doppler (TCD) is one of the initial tools used for monitoring. It measures the mean flow velocities of the middle cerebral artery (MCA), with flow velocity being inversely proportional to arterial radius—thus, higher velocities suggest a greater probability of vasospasm. Indices such as the Lindegaard ratio—which compares flow velocities in the MCA and the extracranial segment of the internal carotid artery—or the Srivi index—used for the posterior circulation—are also employed. The higher the index, the more severe the vasospasm.25,46

Perfusion-focused imaging, CT angiography (CTA), or MR angiography (MRA) can also help identify vasospasm. In patients with high-grade aSAH (WFNS or Hunt & Hess grade 4–5), continuous electroencephalographic (EEG) monitoring is recommended to detect DCI. Typical findings include interictal epileptiform discharges and an alpha/delta wave ratio <50%.25

Nimodipine is the only medication proven to reduce the risk of DCI. It is administered over a 21-day period at a dosage of 60 mg every 4 h.46

Emerging therapiesInnovative therapies, such as goal-directed cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) drainage via lumbar drainage devices, have shown promising evidence for widespread clinical implementation. Initial studies in patients with low-grade aSAH demonstrated reduced rates of delayed cerebral ischemia and improved outcomes during the first 6 months of follow-up, though statistical significance beyond that time frame was not achieved.47

Subsequent studies have shown that lumbar drainage catheters, placed after aneurysm management and maintained for a minimum of 4 days—with drainage targets of 5 ml/h for ideally 8 days—are associated with beneficial functional outcomes extending beyond the initial 6-month period.48

Other therapies, such as intraventricular or intrathecal thrombolysis in patients with aSAH, have not yet demonstrated favorable outcomes with sufficient epidemiological strength to warrant routine clinical use. Large-scale clinical trials are needed to define their relevance in the management of this condition.49

ConclusionThe diagnosis and treatment of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (aSAH) require a comprehensive and effective approach delivered by a multidisciplinary team that is well-versed in the latest advances in management. This approach is essential to improving both the vital and functional prognosis of patients.

Ethical considerationsThis work is a literature review and did not involve human participants or animals. Ethical approval was therefore not required. All sources are appropriately cited, and the work complies with current ethical and academic integrity standards.

FundingThis study did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.