Neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA) comprises a group of rare and heterogeneous genetic disorders, in which early diagnosis can be challenging.

CasesRetrospective review of clinical, neurophysiological, radiological, and molecular data from 18 pediatric NBIA patients (2004–2024): PLAN (n=9), PKAN (n=6), BPAN (n=3). Median age at symptom onset was 12months and at diagnosis 5years, with no significant intergroup differences. Initial symptoms included developmental delay and regression. Key findings: cognitive impairment (100%), dystonia (83%), spasticity (72%). Epilepsy was more frequent in BPAN (100%) than PLAN (44%) or PKAN (16%). MRI findings, including the “eye of the tiger” sign and cerebellar atrophy, aided subtype differentiation. Four PKAN patients underwent DBS-GPi with transient benefit. Mortality was high (61% before 19years), mainly due to respiratory complications.

ConclusionsThis is the largest pediatric NBIA series in Portugal, aiming to improve characterization and differentiation of this disorder group.

La neurodegeneración con acumulación cerebral de hierro (NBIA) comprende un grupo de trastornos genéticos raros y heterogéneos, en los que el diagnóstico temprano puede ser un desafío.

CasosRevisión retrospectiva de los datos clínicos, neurofisiológicos, radiológicos y moleculares de 18 pacientes pediátricos con NBIA (2004–2024): PLAN (n=9), PKAN (n=6), BPAN (n=3). La edad media al inicio de los síntomas fue de 12 meses y al diagnóstico de 5 años, sin diferencias significativas entre los grupos. Los síntomas iniciales incluyeron retraso en el desarrollo y regresión. Hallazgos clave: deterioro cognitivo (100%), distonía (83%), espasticidad (72%). La epilepsia fue más frecuente en BPAN (100%) que en PLAN (44%) o PKAN (16%). Los hallazgos de RM, incluyendo la señal del «ojo de tigre» y atrofia cerebelosa, ayudaron en la diferenciación de subtipos. Cuatro pacientes con PKAN se sometieron a estimulación cerebral profunda (DBS-GPi) con beneficio transitorio. La mortalidad fue alta (61% antes de los 19 años), principalmente debido a complicaciones respiratorias.

ConclusionesEsta es la serie más grande de NBIA pediátrica en Portugal, con el objetivo de mejorar la caracterización y diferenciación de este grupo de trastornos.

Neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA) is a rare, clinically and genetically diverse group of disorders affecting children and adults. Its prevalence is uncertain, but based on prevalence estimates for pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration (PKAN), which accounts for about half of cases, NBIA occurs in about 1 per 500,000 people globally.1 Despite their diverse genetic origins, the shared basal ganglia pathology suggests that iron accumulation is a common feature, likely resulting from protein defects that do not directly regulate iron but interfere with lipid metabolism, mitochondrial function, and autophagy mechanisms.2 Clinical presentations can vary: Classic PKAN manifests in early childhood with rapid progressive dystonia, rigidity, and retinal degeneration, while atypical PKAN presents later with slower progression. Infantile PLAN (PLA2G6-Associated Neurodegeneration) symptoms usually start between 6months and 3years with developmental regression, spastic tetraparesis, cognitive decline, and optic atrophy, while juvenile PLAN features gait instability, ataxia, and slower cognitive decline. BPAN (Beta-propeller Protein-Associated Neurodegeneration) initially presents with developmental delay, seizures, and Rett-like behaviors, followed by progressive dystonia-parkinsonism and cognitive decline.3 Currently, treatment focuses on managing symptoms. Dystonia and spasticity are usually treated with oral medications or Botulinum toxin injections. Deep brain stimulation (DBS) surgery has shown potential benefits, but evidence is limited to case reports and small studies. Physical, occupational, and speech therapies can help delay disease-related complications.4 Algorithms designed to assist clinicians in diagnosing NBIA disorders have limited usefulness due to disease variability, especially in the absence of suggestive findings in Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI).

Case seriesThis retrospective observational study was conducted in a tertiary pediatric hospital in Portugal between May–December 2024 and included patients diagnosed with a NBIA disorder between 2004 and 2024. Data collected from each case included demographic information, family history, clinical manifestations, neurophysiological and neuroimaging results, molecular findings and treatments.

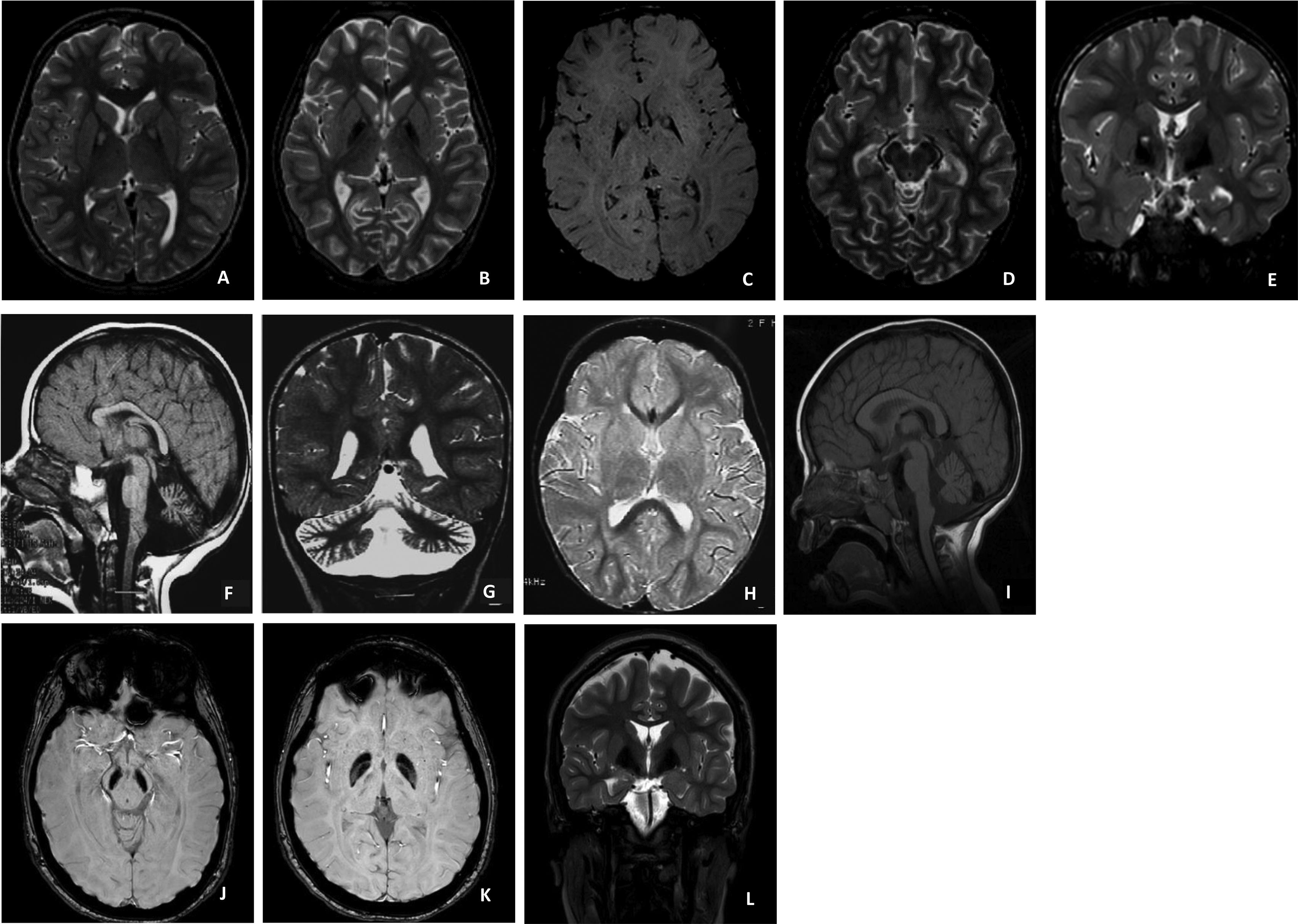

Eighteen individuals diagnosed before the age of 18 were identified, representing 16 families and three different NBIA subtypes: PLAN (9 cases), PKAN (6 cases), and BPAN (3 cases). Parent consanguinity was reported in one case and family recurrence in two. The cohort included 10 males (55.6%) and 8 females (44.4%). Median age at symptom onset was 12months (range: 3–96months) and at diagnosis was 5years (range: 1–14years). Results data are summarized in Table 1.

Results table.

| NBIA type | BPAN | PKAN | PLAN | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | |

| Mutation | WDR45c.1013dup (p.Thr339Hisfs*3)Likely Pathogenic | WDR45c.344+1G>ALikely Pathogenic | WDR45 c.644G>T(p.G215V)VUS | PANK2 c.175_182del AGCGCGTCLikely Pathogenic | PANK2 c.240_241del CA (p.80S>X)Pathogenic | PANK 2 c.240_241delCA (p.80S>X)Pathogenic | PANK 2 c.570_571delCA (p.Y190X) Pathogenic c.1561G>A(p.G521R)Pathogenic | PANK2 c.1537-3C>GPathogenic | PANK2c.570–471(p.Y190X)Likely Pathogenic | PLA2G6c.2032A>G(p.K678E)VUS | PLA2G6 c.2370T>G(p.Y790X)Pathogenic | PLA2G6c.2370T>G (p.Y790X)Pathogenicc.1741A>C (p.K581Q) VUS | PLA2G62370T>G,(p.Y790X)Pathogenic | PLA2G62370T>G,(p.Y790X)Pathogenic | PLA2G6665C>T, (p.T222I)Likely Pathogenic | PLA2G62370T>G, (p.Y790X)Pathogenic 1442T>A, (p.L481Q)Likely Pathogenic | PLA2G62370T>G, (p.Y790X)Pathogenic | PLA2G62370T>G, (p.Y790X)Pathogenic | |

| Heterozygous | Heterozygous | Heterozygous | Homozygous | Homozygous | Homozygous | Double heterozygous | Homozygous | Homozygous | Homozygous | Homozygous | Homozygous | Homozygous | Homozygous | Heterozygous | Compound heterozygote | Homozygous | Homozygous | ||

| Age of symptom onset (months) | 12 | 11 | 5 | 12 | 18 | 3 | 9 | 12 | 12 | 14 | 18 | 96 | 7 | 12 | 18 | 6 | 8 | 13 | |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 14 | 4 | 1 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 10 | 11 | 3 | 9 | 5 | 1 | 10 | 5 | 4 | 3 | |

| Sex | F | M | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | M | M | F | F | M | F | F | M | M | |

| Consanguinity | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| Family history | − | − | − | − | + (sibling 1) | + (sibling 2) | − | − | − | − | − | − | + (sibling 1) | + (sibling 2) | − | − | − | − | |

| Presenting complaints | Generalized seizuresRegression | Generalized seizuresArrest in the acquisition of milestones | Hypotonia Arrest in the acquisition of milestones | RegressionToe walking | Toe walking Frequent falls | Regression | Toe walking Frequent falls | Wide base gait Frequent falls | Regression | Toe walking Frequent falls | RegressionGeneralized Seizures | Difficulties in writingFrequent falls | Could sitwithoutsupport; nofurtherprogress | Could sitwithoutsupport;no further progress | Toe walkingFrequent falls | could sit without support; no further progress | could sitwithoutsupport andcrawl; nofurtherprogress | Regression | |

| Global development delay | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Cognitive impairment | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Stereotypies | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| Epilepsy | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | |

| Age in years at loss of ambulation | − | 4 | Never acquired | 9 | 6 | Never acquired | 6 | 4 | 8 | Requires walker since the age of 12 | Never acquired | 21 | Never acquired | Never acquired | 2 | Never acquired | Never acquired | Never acquired | |

| Ocular manifestations | |||||||||||||||||||

| Visual deficit | − | − | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Oculomotor abnormalities | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | |

| Nystagmus | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | |

| Dysmorphic features | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | ||||||||

| Type of dysmorphia | Facial dysmorphia | − | Pectus carinatum | Ear malformation | − | − | − | − | − | Pectus excavatum | Macrocephaly | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| Extrapiramidal | |||||||||||||||||||

| Generalized dystonia | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | |

| Tremors | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| Bradykinesia | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | |

| Status Dystonicus | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| Ataxia | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | |

| Tone | Rigidity | Hypotonia | Hypotonia | Spasticity | Spasticity | Spasticity | Spasticity | Rigidity | Spasticity | Spasticity | Axial hypotonia Limb rigidity | Spasticity | Spasticity | Spasticity | Spasticity | Spasticity | Hypotonia | Spasticity | |

| Deep tendon reflexes | Normal | Brisk | Brisk | Brisk | Brisk | Brisk | Brisk | Brisk | Brisk | Brisk | Normal | Brisk | Brisk | Normal | Brisk | Brisk | Normal | Brisk | |

| Dysphagia | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | + | |

| Nasogastric tube | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| Percutaneous gastrostomy (age in years at procedure) | − | − | − | − | 10 | − | 9 | − | − | − | 3 | 26 | − | − | − | 5 | − | − | |

| Noninvasive ventilation | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| EEG | Paroxysmal bilateral paracentral epileptiform activity | Frequent bilateral anterior epileptiform activity | Paroxysmal right central and left frontocentral epileptiform activity. Generalized slow BA activity | No relevant findings | Slow and poorly structured BA.Rare paroxysmal sharp-wave epileptiform activity with right frontal localization | No relevant findings | Slow and poorly structured BA | No relevant findings | No relevant findings | Multifocal epileptiform activity with marked left temporal predominance | No relevant findings | Slow and poorly structured BA | Generalized high voltage fast rhythms (18–20Hz) | Few occipital dominant high voltage(70–100mV)fast rhythms (18–22Hz). Normal BA(14 mo) | Diffuse high amplitude(50–160mV) fast rhythms (16Hz) | Diffuse high-voltage (50–150mV)fast rhythms (18–22Hz) | No relevant findings | High amplitude(70–110mV) fast rhythms (18–20Hz)Slow BA | |

| MRI | T2G. pallidi Hyperintense signal surrounded by hypointense signal “eye of the tiger” sign | Significant global enlargement of CSF spaces. Some paucity of white matter is also noted. | Enlarged posterior fossa with fluid-equivalent content. The cerebellar vermis is mildly reduced in its lower portion | T2G. pallidi Hyperintense signal surrounded by hypointense signal “eye of the tiger” sign | T2G. pallidi Hyperintense signal surrounded by hypointense signal “eye of the tiger” sign | T2G. pallidi Hyperintense signal surrounded by hypointense signal “eye of the tiger” sign | T2G. pallidi Hyperintense signal surrounded by hypointense signal “eye of the tiger” sign Volume loss in both pallidi | T2G. pallidi Hyperintense signal surrounded by hypointense signal “eye of the tiger” sign | T2G. pallidi Hyperintense signal surrounded by hypointense signal “eye of the tiger” sign | Marked cerebellar atrophy, with no other significant abnormalities | T2 substantia nigra, midbrain and globus pallidus HypointensityCerebellar atrophyBrain volume loss | T2G. pallidi Hyperintense signal surrounded by hypointense signal “eye of the tiger” sign | Cerebellar atrophy | Cerebellar atrophy. T2hyperintensity in cerebellar cortexHyperintensity of cerebral white matter.T2GP hypointensity | Cerebral and cerebellaratrophy. T2 hyperintensity incerebellar cortex and cerebral white matterT2GP hypointensity | Cerebral and cerebellar atrophy Thin corpus callosum T2GP Hypointensity | Cerebellar atrophy with T2 Hyperintensity in cerebellarcortex | Cerebellar atrophy withT2 hyperintensity in cerebellarCortex and cerebralWhite matter | |

| DBS (age at procedure) | − | − | − | 9 | 10 | 7 | 9 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| Target | Globus pallidus internus | Globus pallidus internus | Globus pallidus internus | Globus pallidus internus | |||||||||||||||

| Response | Positive: Transient resolution of status dystonicus | Positive: Improvement of dystonic posture | Positive: Brief improvement followed by clinical decline | No response | |||||||||||||||

| Oral treatment | |||||||||||||||||||

| Levodopa | − | − | +(worsened) | + (transient response) | − | +(no response) | − | − | +(no response) | − | − | + (adverse reaction) | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| Coenzime q10 | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| MCT oil | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| Botulinum toxin | − | − | + (Sialorrhea) | + (Dystonia) | + (Dystonia) | − | + (Dystonia) | + (Dystonia) | + (Spasticity) | − | + (Dystonia) | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| Therapies | |||||||||||||||||||

| Physiotherapy | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Speech therapy | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | |

| Occupational therapy | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Outcome (Death, at age - years) | − | − | − | − | + (13) | + (9) | + (10) | − | + (18) | − | + | − | + (7) | + (10) | + (16) | + (9) | + (8) | + (6) | |

+ present; − absent.

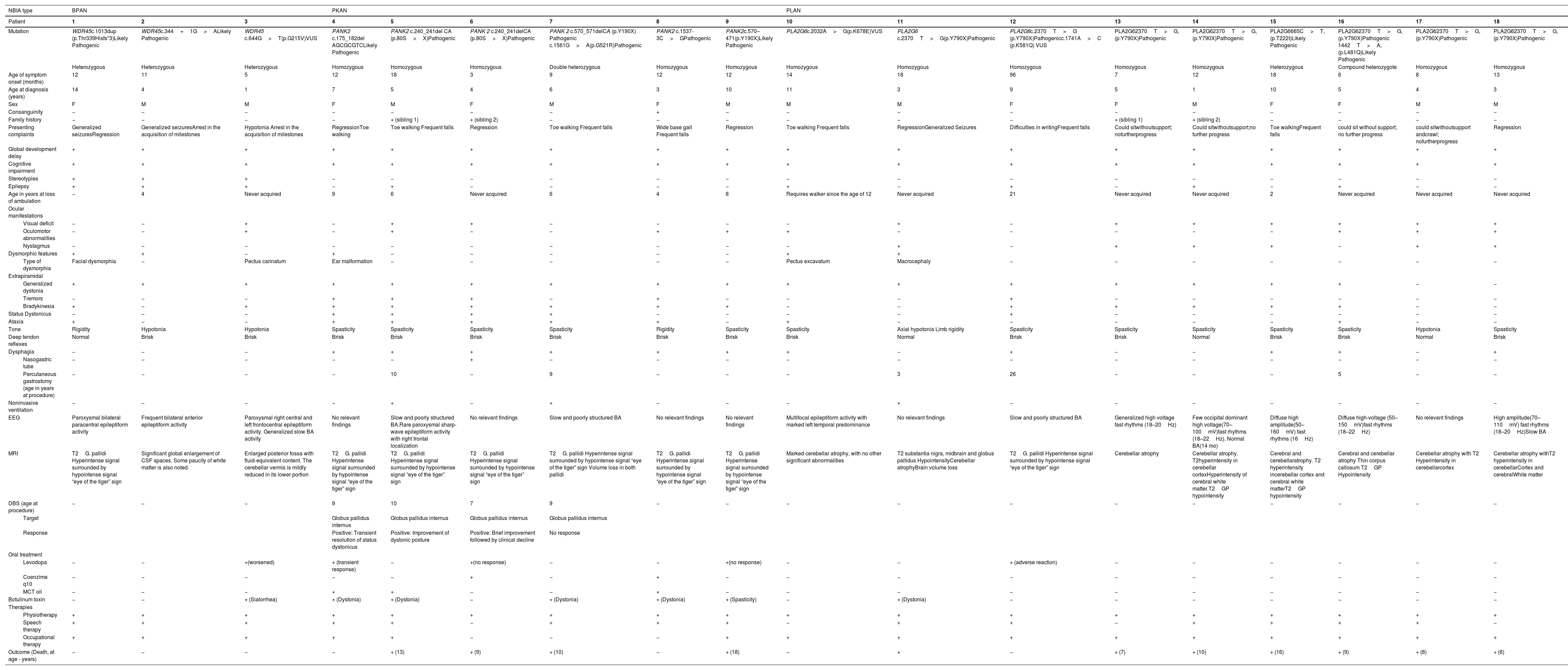

This group included three patients (2 males, 1 female). Median age at symptom onset was 11months (range: 5–12months), and at diagnosis 4years (range: 1–14years). Presenting symptoms included seizures (n=2), arrest in the acquisition of milestones (n=2), and regression (n=1). Generalized dystonia and sporadic midline hand stereotypies were present in all patients, while ataxia and ocular manifestations were each observed in only one case. Dysmorphic features included facial dysmorphia (n=1) and pectus carinatum (n=1). Epilepsy was present in all patients, with EEG findings revealing multifocal and generalized discharges. Brain MRI demonstrated iron deposits in one patient (Fig. 1; images J, K and L); cerebral and cerebellar atrophy in the other two. Regarding treatment, all patients were on anti-seizure medication, and only one presented with refractory epilepsy. Levodopa was tried in one case, leading to adverse effects. One patient received Botulinum toxin for sialorrhea, with positive results. All patients were alive at the time of the study (ages 4, 6, and 14years).

Pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration (PKAN).

A (Patient 4) and B (Patient 6): Axial T2 – Hyperintense signal surrounded by hypointense signal in globus pallidus, “Eye of the tiger” sign; C (Patient 7): Axial SWI – Hypointense pallidal signal; D (Patient 6): Axial T2 – Hypointense substantia nigra; E (Patient 7): Coronal T2 – Hypointense pallidal signal with central high signal.

Phospholipase A2-associated neurodegeneration (PLAN).

F, G and H (Patient 16): Sagittal T1 (F); coronal T2 (G) and axial T2 (H): Cerebellar atrophy mainly involving the inferior part of the vermis, with signal hyperintensity in cerebellar cortex (T2); D (Patient 11): T1 sagittal – Cerebellar atrophy.

Beta-propeller protein-associated neurodegeneration (BPAN).

J and K (Patient 1): Axial SWI – Hypointense signal in the substantia nigra and pallidum; L (Patient 1): Coronal T2– Hypointense pallidal signal.

Six patients (3 males, 3 females) were included. Median age at symptom onset was 12months (range: 3–18months), and at diagnosis 5.5years (range: 3–10years). All patients exhibited the classic form of PKAN, presenting with regression (n=3) and gait disturbances (n=4) such as toe-walking and frequent falls. The most common symptoms included severe generalized dystonia, with pronounced oromandibular dystonia (n=6); ataxia (n=5); oculomotor abnormalities (n=3); visual deficits in relation with pigmentary retinopathy (n=2), and focal epilepsy (n=1), controlled with a single drug. Dysphagia affected four patients, requiring gastrostomy in two. Status dystonicus occurred in four patients, all of whom underwent DBS surgery of the internal globus pallidus (GPi) between the ages of 7 and 10years. Three patients experienced transient improvement, while one showed no benefit. All surgical candidates were in an advanced stage of the disease, with refractory dystonic status. EEG revealed slow background activity with bilateral asynchronous discharges in two patients. Brain MRI consistently showed T1 hyperintensity and peripheral hypointensity with a central hyperintense area on T2 in the globus pallidus, characteristic of the ‘eye of the tiger’ sign (Fig. 1; images A-E). Treatments included trihexyphenidyl (n=6), baclofen (n=4), coenzyme-Q10 (n=2), and Medium-Chain-Triglyceride oil (n=3), with no clear benefit from the latter two. One of three patients treated with levodopa experienced a transient benefit. Botulinum toxin was used for dystonia (n=4) and spasticity (n=1), with good results. Supportive therapies included physiotherapy (n=6), speech therapy (n=5), and occupational therapy (n=3). Mortality rate was 66.7% (4/6), with a median age at death of 10years (range: 9–18years), due to complications related to respiratory tract infections.

PLA2G6-associated neurodegeneration (PLAN) casesThis group included nine patients (4 females, 5 males), five previously reported.5 The most frequent mutation (PLA2G6 c.2370T>G, p.Y790X) was found in seven cases. The median age at symptom onset was 13months (range: 6–96months), and at diagnosis 5years (range: 1–11years). Common presenting complaints were development delay (n=4), gait abnormalities (n=3), and regression (n=2). The most common symptoms included generalized dystonia (n=7); ocular manifestations such as visual deficits due to optic atrophy (n=7), nystagmus (n=6) and oculomotor abnormalities (n=4); epilepsy (n=4); ataxia (n=2) and dysmorphic features, macrocephaly (n=1) and pectus excavatum (n=1). Dysphagia was present in five patients, with three requiring gastrostomy. EEG findings varied, showing high-voltage fast rhythms in five patients and multifocal epileptiform activity in one. Electromyography showed signs of denervation with normal nerve conduction velocity (n=4). Brain MRI revealed cerebellar atrophy (n=8); additional findings included thin corpus callosum and globus pallidus hypointensities (Fig. 1; images F-I). Regarding treatments, Levodopa led to adverse effects in one patient, and Botulinum toxin effectively managed dystonia in one case. Supportive therapies were widely utilized. Mortality rate was 77.8% (7/9), with a median age at death of 8.5years (range: 6–16).

DiscussionThis study provides an overview of 18 individuals diagnosed with three NBIA subtypes before 18years. The predominance of PLAN (50%) and PKAN (33%) aligns with Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD) data on the most common NBIA subtypes.6 Family history showed only one case of consanguinity, suggesting lower inbreeding in the studied population, and two cases of familial recurrence, possibly explained by diagnostic delay.

The male-to-female ratio of 10:8 is consistent with previous studies showing no gender predisposition. Two male BPAN patients were identified, which is rare due to its X-linked inheritance. Male cases typically result from de novo mutations or somatic mosaicism and tend to present with more severe symptoms.7 Both had earlier symptom onset and lost the ability to walk before 5years.

Overall, the median age at symptom onset was 12months, with most patients presenting before the age of two, confirming early onset. The diagnostic delay (median age of 5years) is likely attributed to the rarity of NBIA and the overlap of its phenotypes with other neurodegenerative conditions. Common presenting complaints included gait abnormalities (39%), development delay (33%), and regression (33%). Extrapyramidal symptoms were present in 89%, most commonly dystonia (83%), in line with previous studies identifying dystonia and Parkinsonism, as hallmarks of NBIA.1 Visual deficits were observed in 56%, higher in PLAN (77.8%), where they are a characteristic finding.8 Epilepsy was diagnosed in 44% of the cases, most frequently in the BPAN (100%) and PLAN (44.4%) groups. A recent review further emphasized that seizures are a common feature of NBIA, particularly in BPAN (72.1%) and PLAN (50.8%).9 Most patients (89%) were unable to walk independently, with 44% never achieving ambulation and 50% losing the ability by a median age of 8.5years.

Neuroimaging showed cerebellar atrophy in PLAN (88.9%) and the “eye of the tiger” sign in PKAN (100%), supporting its diagnostic utility.1

Overall mortality rate was 61.1% (11/18), highest in PKAN (66.7%) and PLAN (55.6%) groups. Treatment was primarily supportive, though four PKAN patients underwent DBS-GPi, resulting in only a transient dystonia improvement, likely due to the advanced stage of their disease. This aligns with recent reports showing that while DBS can reduce dystonia severity but its long-term benefits may be inconsistent or limited to specific subtypes, particularly atypical PKAN.10

This series represents the largest cohort of pediatric NBIA patients in Portugal, highlighting diverse clinical presentations. Limitations include the lack of functional testing for newly discovered variants. Ongoing molecular advancements and research are crucial for an earlier diagnosis and the development of effective therapies.

Author rolesSL: 1A, 1B, 1C, 2A, 2B, 3A; MR: 1B, 1C, 3A; IM: 1C, 3A; IC: 1A, 1C, 3B; CG: 1C, 2C, 3B; MS: 1B, 3B; SF: 1B, 3B; JM: 1B, 3B; JC: 1B, 3B; TT: 1A, 1B, 2C, 3B.

- 1.

Research project: A. Conception, B. Organization, C. Execution;

- 2.

Statistical Analysis: A. Design, B. Execution, C. Review and critique;

- 3.

Manuscript Preparation: A. Writing of the first draft, B. Review and critique;

No specific funding was received for this work.

Funding sourcesNo specific funding was received for this work.

Financial disclosures for the previous 12 monthsThe authors declare that there are no additional disclosures to report.

Ethical compliance statementThe authors confirm that the approval of an institutional review board was not required for this work. Verbal informed patient consent was obtained for this work. We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this work is consistent with those guidelines.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest relevant to this work.