Hemoglobin E/β-thalassemia is a prevalent form of thalassemia in Southeast Asia and parts of the Indian subcontinent, accounting for nearly half of all severe thalassemia cases globally.1–3 Extramedullary hematopoiesis (EMH), a compensatory mechanism in chronic anemias, may involve atypical sites such as the paraspinal region, occasionally causing spinal cord compression.4 Moyamoya angiopathy (MMA) is a chronic steno-occlusive cerebrovascular disorder characterized by progressive narrowing of the intracranial internal carotid arteries with compensatory collateral vessel formation.5–8 The simultaneous occurrence of HbE/β-thalassemia and MMA is extremely rare.9,10

We report a unique case of a young woman with previously unrecognized HbE/β-thalassemia, presenting with bilateral intrathoracic EMH and MMA-related ischemic stroke triggered by spicy food consumption and febrile illness.

A 34-year-old woman from West Bengal, India, presented to the emergency department with involuntary shaking of her right limbs following spicy food ingestion. These movements evolved into right-sided hemiparesis. Since age 14, she had experienced similar transient episodes—brief, unilateral limb-shaking episodes triggered by hot/spicy food, each lasting 2–3min without loss of consciousness. These had been misattributed to a psychogenic movement disorder and depression.

She reported multiple prior hospitalizations for blood transfusions, typically following acute febrile illnesses or significant bleeding episodes (e.g., malaria, undifferentiated febrile illness, and menorrhagia). The etiology of her anemia had not been investigated.

At admission, she was febrile, pale, and icteric, with chronic hemolytic facies (frontal bossing, malar prominence, depressed nasal bridge) and hepatosplenomegaly. The neurological examination showed a right spastic hemiparesis (MRC 4/5), spastic dysarthria, with preserved sensory and cerebellar functions.

Laboratory results showed severe microcytic, hypochromic anemia with anisopoikilocytosis, a reticulocyte index of 4.5, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and relative lymphocytosis. Liver enzymes were mildly elevated with indirect hyperbilirubinemia. Serum LDH increased, and haptoglobin was decreased. Coombs tests were negative. High-performance liquid chromatography confirmed HbE/β-thalassemia. Scrub typhus IgM was positive; other infectious serologies were negative.

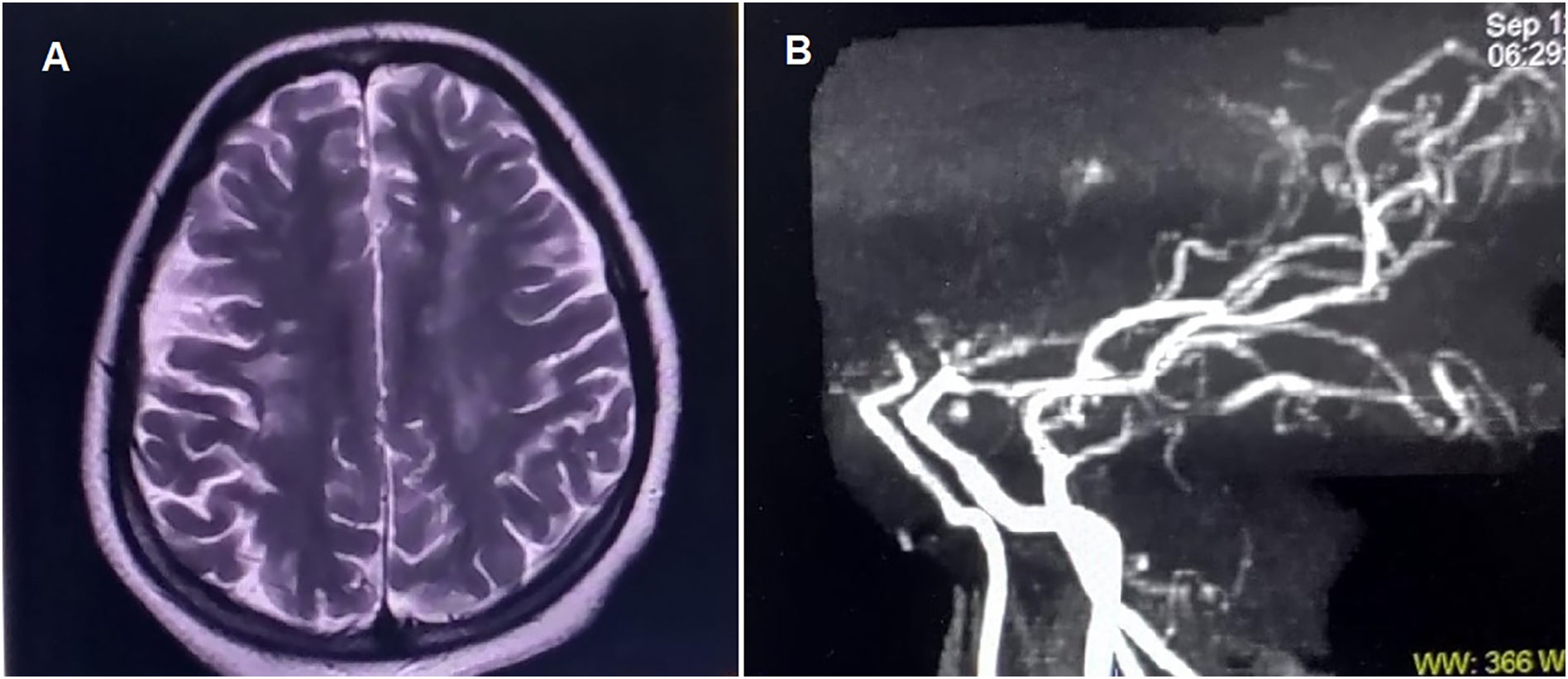

Chest radiograph revealed bilateral paravertebral masses of heterogeneous density. Brain MRI demonstrated multifocal subacute infarcts in the left frontoparietal, paraventricular, and centrum semiovale regions, along with chronic angiopathic changes in the contralateral hemisphere (Fig. 1A). Flow voids in bilateral internal carotid, anterior cerebral, and middle cerebral arteries were absent; the “ivy sign” was observed. MR angiography confirmed the presence of MMA (Fig. 1B).

(A) Brain magnetic resonance imaging shows multiple hyperintense lesions on T2-weighted sequences in the left frontoparietal, paraventricular, and anterior centrum semiovale regions, consistent with subacute non-hemorrhagic infarcts. Additional non-enhancing discrete and confluent hyperintense lesions in the right periventricular white matter and centrum semiovale on T2-weighted and FLAIR images are suggestive of chronic angiopathic changes.

(B) Magnetic resonance angiography (sagittal view) shows an abrupt cut-off of flow at the supraclinoid segment of both internal carotid arteries, just proximal to the bifurcation into anterior and middle cerebral arteries. The left internal carotid artery appears narrower than the right. The posterior circulation (vertebral, basilar, and distal branches) remains intact, supplying the anterior circulation, a finding characteristic of Moyamoya angiopathy.

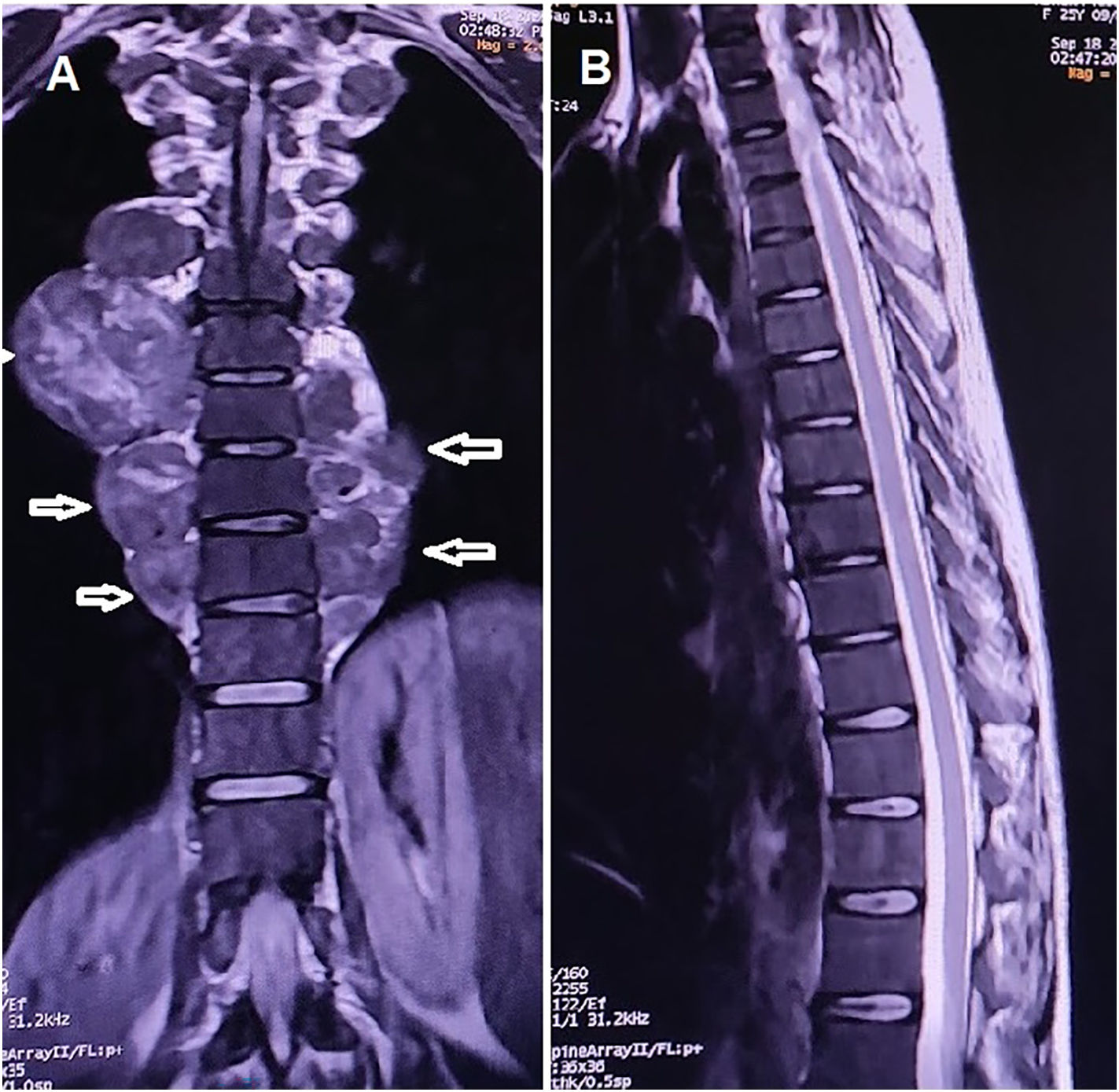

Thoracic MRI revealed bilateral paravertebral masses without spinal cord compression (Figs. 2A–B). CT-guided FNAC confirmed extramedullary hematopoiesis.

The patient was diagnosed with previously unrecognized HbE/β-thalassemia, MMA, and intrathoracic EMH. She responded favorably to packed red blood cell transfusions and doxycycline. Radiotherapy for EMH and surgical revascularization were deferred at the patient's preference. She was discharged on folic acid, hydroxyurea, and aspirin, with counseling to avoid spicy foods, temperature extremes, and strenuous activity.

To our knowledge, this is the first reported adult case of HbE/β-thalassemia presenting with bilateral paravertebral masses due to EMH in the absence of spinal cord compression.4 This finding underscores the need to consider EMH in the differential diagnosis of patients with unexplained anemia and paravertebral masses. In such cases, early diagnostic workups, including hemoglobin electrophoresis, are essential, as timely identification of HbE/β-thalassemia can guide appropriate management strategies and potentially improve clinical outcomes.

Our patient also had a long-standing history of limb-shaking transient ischemic attacks, a phenomenon that may be underrecognized in MMA, particularly in pediatric populations.11 The coexistence of MMA and HbE/β-thalassemia is uncommon and pathophysiologically intriguing. While Moyamoya disease is classically idiopathic, its occurrence in the setting of chronic hemolytic anemia raises the possibility of a compensatory vascular response to persistent tissue hypoxia.5–10 Chronic anemia, as seen in thalassemia, may lead to long-standing cerebral hypoxemia, which in turn could promote angiogenic remodeling and the development of the fragile collateral vasculature characteristic of MMA.9,10 Although this mechanism remains speculative, it merits further investigation. Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for cerebrovascular abnormalities in patients with severe thalassemia, especially those with neurological symptoms.

The ischemic strokes observed in our patient, particularly those triggered by hot or spicy food, are exceedingly rare and poorly understood.12 One possible explanation is that these stimuli elicit sudden alterations in cerebral blood flow, which, in the context of a compromised vascular architecture, may precipitate ischemia. However, the exact pathophysiological mechanism remains elusive, underscoring the need for additional research into trigger-induced cerebrovascular events in MMA.

An additional point of interest in this case was the patient's seropositivity for scrub typhus IgM. Scrub typhus, caused by Orientia tsutsugamushi, is endemic to the Indian subcontinent and often presents as an acute, undifferentiated febrile illness.13–15 Although this infection has been associated with a wide range of neurological complications, its relevance in the present case remains uncertain. It is plausible that febrile illness acted as a precipitant for ischemic symptoms secondary to MMA and contributed to a hemolytic crisis, exacerbating the underlying anemia. Nevertheless, the chronicity of the patient's primary neurological symptoms suggests that the scrub typhus infection was likely incidental.

In conclusion, this case illustrates the complex interplay of hematologic, infectious, and neurovascular disorders, manifesting in a unique and diagnostically challenging clinical presentation. The unusual co-occurrence of HbE/β-thalassemia, intrathoracic EMH without spinal involvement, and MMA underscores the necessity of broad diagnostic consideration in patients with atypical neurological symptoms and chronic anemia. Recognition of such rare associations is essential for informed clinical decision-making and improved patient care.

Author’s noteWritten informed consent was obtained from the patient participating in the study (consent for research).

Author contributionsAll authors contributed significantly to the creation of this manuscript: Drafting/revision of the manuscript for content, including medical writing for content; significant role in the acquisition of data; study concept or design; and analysis or interpretation of data. Each fulfilled the criterion established by the ICMJE.

Study fundingThe authors report no targeted funding.

DisclosuresDr. Ritwik Ghosh (ritwikmed2014@gmail.com) reports no relevant disclosures.

Dr. Moisés León-Ruiz (pistolpete271285@hotmail.com) reports no relevant disclosures.

Dr. Shambaditya Das (drshambadityadas@gmail.com) reports no relevant disclosures.

Dr. Souvik Dubey (drsouvik79@gmail.com) reports no relevant disclosures.

Dr. Julián Benito-León (jbenitol67@gmail.com) reports no relevant disclosures.

Ethical considerationsThis study is a single-patient case report. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of clinical information and images. Ethical approval from an institutional review board was not required, as the case was descriptive and did not involve experimental interventions.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Julián Benito-León is supported by the Recovery, Transformation, and Resilience Plan of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (grants TED2021-130174B-C33, NETremor, and PID2022-138585OB-C33, Resonate) and by the National Institutes of Health (NINDS R01 NS39422 and R01 NS094607).