Narcolepsy is a chronic neurological disorder characterized by excessive daytime sleepiness and abnormal rapid eye movement manifestations, such as cataplexy, sleep paralysis, and hypnagogic hallucinations. Symptoms usually begin in childhood or adolescence, and diagnosis is often delayed. Treatment typically involves wake-promoting agents, antidepressants, and more recently, histamine H3 receptor antagonists like pitolisant. Given its complexity, real-world evidence on treatment strategies is needed.

Objectives and patientsThis study describes three clinical cases of narcolepsy treated with pitolisant and followed longitudinally, focusing on clinical response, dose adjustments and functional outcomes. Case one involves an eight-year-old girl with excessive daytime sleepiness, later developing cataplexy. Pitolisant was titrated to 18 mg/day. In case two, a six-year-old boy presented with severe hypersomnia, cataplexy, hallucinations, and Tanner stage II pubertal development. Pitolisant started at 4.5 mg/day, increased to 9 and then to 13.5 mg/day. Case three concerns a 49-year-old man whose childhood-onset symptoms evolved into hypersomnolence, snoring, and non-restorative sleep. Pitolisant was started at 9 mg/day, increased to 36 mg/day, and then reduced to 18 mg/day.

ResultsAt five months, case one reported near-normal functioning. In case two, daytime sleepiness resolved, school attendance resumed, weight stabilized, and pubertal progression halted. In case three, Epworth Sleepiness Scale scores dropped, and the patient remained stable.

ConclusionsThese cases illustrate diagnostic complexity and the need for personalized treatment. Pitolisant proved effective in improving excessive sleepiness, cataplexy, and functioning. The findings underscore the importance of early diagnosis, tailored pharmacotherapy, and real-world clinical data to refine management, especially in complex cases.

La narcolepsia es un trastorno neurológico crónico caracterizado por somnolencia diurna excesiva y alteraciones del sueño REM, como cataplejía, parálisis del sueño y alucinaciones hipnagógicas. Los síntomas suelen comenzar en la infancia o adolescencia, con frecuente retraso diagnóstico. El abordaje terapéutico incluye agentes promotores de la vigilia y antidepresivos, y recientemente se ha incorporado el antagonista H3 de histamina pitolisant. Dada la complejidad fisiopatológica del trastorno, resulta imperativa la generación de evidencia práctica sobre estrategias de manejo terapéutico.

Objetivos y pacientesEste estudio describe tres casos clínicos de narcolepsia tratados con pitolisant y seguidos longitudinalmente, enfocándose en la respuesta clínica, ajustes de dosis y resultados funcionales. El caso uno corresponde a una niña de ocho años con somnolencia diurna y cataplejía, tratada con pitolisant hasta 18 mg/día. El caso dos refiere a un niño de seis años con hipersomnia severa, cataplejía, alucinaciones hipnagógicas y desarrollo puberal estadio II de Tanner, con incremento de dosis hasta 13,5 mg/día. El caso tres describe a un hombre de 49 años con síntomas desde la infancia, evolucionando a hipersomnia, ronquidos y sueño no reparador. Se tituló pitolisant hasta 36 mg/día, luego reducido a 18 mg/día.

ResultadosA los cinco meses, la primera paciente recuperó funcionalidad casi normal. En el segundo, se resolvió la somnolencia y se reanudó la asistencia escolar. El tercero mostró descenso en la Escala de Somnolencia de Epworth y estabilidad clínica.

ConclusionesLos casos destacan la complejidad diagnóstica y la necesidad de tratamiento individualizado. Pitolisant demostró eficacia clínica y funcional.

Narcolepsy is a chronic neurological disorder characterized by excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) and abnormal manifestations of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, such as cataplexy, sleep paralysis, and hypnagogic hallucinations.1 Symptoms typically begin in childhood or adolescence, and in a large proportion of patients, diagnosis and treatment are delayed despite the disabling nature of the condition.2 The condition is typically divided into two subtypes: narcolepsy type 1 (NT1), which includes cataplexy and/or low cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) hypocretin-1 levels, and narcolepsy type 2 (NT2), in which cataplexy is absent and hypocretin levels are usually normal.3

Despite its relatively low prevalence, narcolepsy imposes a substantial burden on patients' quality of life, academic or occupational functioning, and psychosocial development.4 EDS can lead to significant safety risks, particularly in professions requiring sustained attention, such as driving.5 In pediatric cases, symptoms are often under-recognized or misattributed, leading to delayed diagnosis and treatment.6

Treatment of narcolepsy typically involves the use of wake-promoting agents (e.g., modafinil, methylphenidate), antidepressants for REM-related symptoms, and more recently, histamine H3 receptor antagonists such as pitolisant.7 Pitolisant has shown efficacy in reducing EDS and cataplexy, and its non-scheduled status offers a practical advantage over other stimulants.8 Nevertheless, treatment responses can vary widely across individuals, and the management of residual symptoms remains a frequent challenge.9

One of the main therapeutic challenges in narcolepsy is the persistence of symptoms despite optimized pharmacologic treatment, particularly in cases with comorbidities such as obesity or obstructive sleep apnea.10 In children, treatment must also consider the impact on growth, development, and school performance.6 Additionally, clinical heterogeneity and the evolving nature of symptoms over time underscore the need for individualized approaches.9

Given the complex clinical presentation and management of narcolepsy, especially in pediatric and occupationally vulnerable populations, there is a pressing need for detailed clinical case reports that can inform real-world therapeutic strategies and outcomes. Descriptive data on response to newer agents like pitolisant, dose titration, tolerability, and interaction with comorbid conditions are also particularly valuable.

The aim of this study was to describe three clinical cases of narcolepsy—two pediatric and one adult—with varying phenotypes and therapeutic trajectories. All cases were treated with pitolisant and followed longitudinally, with attention to clinical response, dose adjustments, comorbid conditions, and functional outcomes.

Material and methodsThe presented cases were the winners of the contest “Abre los Ojos en Narcolepsia”, selected by a jury of experts (Dr. Juan José Poza, Neurology Service, Hospital Universitario de Donostia, San Sebastian, Spain; Dra. Roser Cambrodi (Neurophysiology Service, Hospital Vall d'Hebron, Barcelona, Spain; Dr. Francisco Javier Martínez (Neurophysiology Service, Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Madrid, Spain). The contest was promoted by Bioprojet Spain and endorsed by the Spanish Sleep Society.

Three cases of narcolepsy were admitted to three different hospitals in Spain. Case 1 was seen in the Department of Pediatrics and Pediatric Neurology at Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet. Case 2 was managed at the Sleep Unit of the Clinical Neurophysiology Department at Hospital General Universitario de Castellón. Case 3 was admitted to the Clinical Neurophysiology Department at Hospital Central de la Defensa Gómez Ulla.

Written informed consent for participation in the study was obtained from all patients (consent for research). The data supporting the findings of this study are included within the article.

ResultsCase 1An eight-year-old girl was referred for evaluation of EDS. She had no relevant past medical history, and both neurodevelopment and physical examination were normal. Symptoms began two years earlier (at age six), coinciding with the cessation of regular daytime naps. Her sleep routine consisted of going to bed between 9:30 p.m. and 10:00 p.m., although she occasionally fell asleep as early as 8:30 p.m. without eating dinner. Nocturnal sleep was reportedly unfragmented, with no nightmares, and she routinely woke around 8:00 a.m.

During school hours, she became notably drowsy and needed to wash her face to stay alert. In the afternoon, she typically took a nap from 2:00 p.m. to 4:00 p.m. unless awakened. When nap duration was limited to one hour or less, she had difficulty participating in sports and would wake up irritable, though she eventually completed training. She fell asleep easily in the car and had once fallen asleep in the bathtub. No cataplexy was initially reported.

The initial workup -including laboratory tests, brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), ophthalmologic assessment, electroencephalogram (EEG), and overnight polysomnography (PSG)- was unremarkable. She was started on immediate-release methylphenidate, administered at breakfast and lunch, resulting in modest clinical improvement – most notably improved tolerance of morning activities and elimination of evening sleep attacks before dinner.

An overnight PSG followed by a Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT) revealed a mean sleep latency of 3.7 min and four sleep-onset rapid eye movement periods (SOREMPs), with an additional SOREMP observed during PSG. The sleep onset latency (2 min) is decreased, as well as the sleep latency to the first REM sleep (5.5 min).

Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) testing showed HLA-DQA101, HLA-DQB1*06, and HLA-DRB113 DRB115. CSF hypocretin-1 level was 32.20 pg/mL. Testing for anti–N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (anti-NMDAR) and anti–myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (anti-MOG) antibodies was negative in both serum and CSF. Endocrine evaluation for premature pubarche excluded central precocious puberty.

Twelve months after referral (at age nine), the patient developed partial cataplexy triggered by laughter, characterized by upward gaze and occasional mild knee buckling without falls. Academic performance remained satisfactory. However, she continued to experience afternoon functional impairment due to EDS, despite various methylphenidate regimens.

Pitolisant treatment was prescribed and titrated up to 18 mg/day (body weight <40 kg). After two months, both parents and teachers reported marked improvement, with the patient described as “happier than ever.” Initial mild headache and insomnia resolved, and she recovered more efficiently from shorter naps. At the five-month follow-up, the patient and her family reported a near-normal daily life.

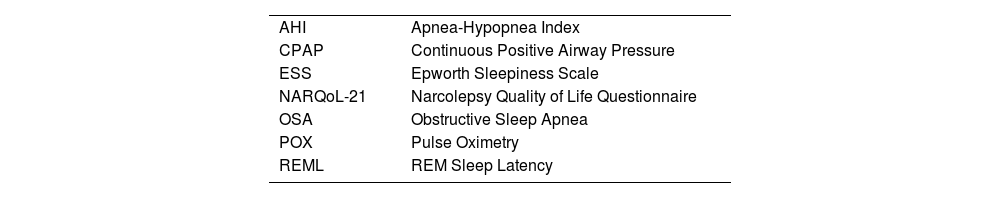

Daytime sleepiness and quality-of-life assessments before and five months after starting pitolisant were as follows: Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS),11 12–9; Modified ESS for Children,12 10–9; Ullanlinna Narcolepsy Scale,13 20–15; NARQoL-21,14 66–61.

Case 2A six-year-old boy presented with severe hypersomnia following a viral exanthematous illness. He was sleeping approximately 10 h at night and taking daytime naps of up to four hours. Additionally, he experienced uncontrollable sleep attacks, frequently falling asleep in the car and during class. An urgent cranial CT scan was performed and showed no abnormalities.

Shortly after the onset of hypersomnia, his parents noted a marked increase in appetite, a weight gain of 7 kg over two months, and the development of secondary sexual characteristics, including axillary and pubic hair and strong body odor. Bone age assessment revealed maturation consistent with chronological age. Brain MRI was normal. Laboratory investigations demonstrated elevated 17-hydroxyprogesterone (1.79 ng/mL) and testosterone (0.190 ng/mL). He was classified as Tanner stage II for pubertal development.

Clinical history revealed significant EDS and cataplexy, characterized by lower limb weakness and ptosis triggered by laughter. The patient also reported frequent hypnagogic hallucinations. Polysomnography showed pronounced sleep fragmentation and frequent stage transitions. MSLT demonstrated a mean sleep latency of 2.8 min, with SOREMPs in all four naps. HLA typing was positive for DQB1*06:02. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of narcolepsy type 1 was established.

Pitolisant therapy was initiated at 4.5 mg/day and increased to 9 mg/day in the second week. After one month, clinical improvement was noted, with decreased sleepiness, improved energy levels, reduced appetite, weight stabilization, and no further progression of pubertal signs. At three months, occasional daytime sleepiness and partial cataplexy were observed, but weight remained stable, and no further sexual maturation occurred. At four months, EDS recurred, along with slight weight gain and further axillary and pubic hair growth. The dose of pitolisant was increased to 13.5 mg/day. By the fifth month, daytime sleepiness had resolved, the patient resumed normal school attendance and regular sports participation, and only sporadic partial cataplexy persisted. His weight had stabilized, pubertal progression had ceased, and serum testosterone levels had decreased to 0.178 ng/mL.

Case 3A 49-year-old man was referred to the Clinical Neurophysiology Department for hypersomnolence, snoring, non-restorative sleep, postprandial afternoon sleep attacks, and non-refreshing short naps. He scored 23 out of 24 on the ESS. Symptoms began in childhood with sleep attacks and progressively evolved to include his current clinical picture. He denied cataplexy, vivid dreams, or sleep paralysis. His past medical history was significant for treatment-resistant hypertension on three antihypertensives and obesity (Body Mass Index = 32.2). He worked as a bus driver.

A sleep diary and in-laboratory PSG were obtained. PSG findings indicated moderate obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), with an apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) of 24. REM sleep latency (REML) was 5.5 min. One month later, he underwent continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) titration, followed by an MSLT. Optimal titration was achieved with CPAP at 9 cm H2O, with REML reduced to 3.5 min. MSLT showed a mean sleep latency of 1 min and two SOREMPs. These findings supported a diagnosis of narcolepsy type 2, and a workplace accommodation was requested.

CPAP therapy at 9 cm H2O was initiated, with follow-up via pulse oximetry. The patient showed good OSA control (<5 desaturations per hour) and progressive improvement in daytime sleepiness. At nine months, ESS scores stabilized between 12 and 14. Due to residual EDS and high cardiovascular risk, pitolisant was initiated at 9 mg/day and titrated according to the product label to 36 mg/day. This led to an ESS score of 6 out of 24, the best observed. However, after a few days, he reported headache and anxiety, prompting a dose reduction to 18 mg/day by mutual agreement. Since then, he has remained stable on approximately 22.5 mg/day. Due to weight gain and increased desaturation events on POX, CPAP pressure was increased to 10.5 cm H2O.

DiscussionThe three clinical cases presented in this study highlight several key aspects and challenges in the diagnosis and management of narcolepsy across different age groups and clinical contexts. These cases illustrate the diagnostic complexity and the need for personalized treatment, especially in the presence of comorbidities. Also, all cases involved the use of pitolisant, which emerged as a central element in the therapeutic strategy and underscores its relevance as a modern pharmacological option for narcolepsy.

Regarding the diagnostic process, the cases presented exemplify the challenges encountered across different patient profiles. This is particularly evident in children, where atypical symptoms often lead to misdiagnosis or missed diagnoses of narcolepsy.15 Accurate diagnosis in both pediatric cases required a comprehensive battery of objective assessments, including PSG, the MSLT, HLA typing, and in one instance, CSF hypocretin-1 analysis. In Case 1, diagnosis was delayed by over two years, partly because the patient was not referred to a neurology unit. Symptoms developed gradually after stopping regular naps and did not initially show typical signs of narcolepsy, such as cataplexy. This case shows the need for strong clinical suspicion to ensure timely diagnosis and improve quality of life. Although delayed diagnosis is still a concern, growing awareness and earlier clinical suspicion have made it possible to identify narcolepsy sooner, as in Case 2. Early recognition also helps detect age-specific symptoms. In children, narcolepsy may appear as hyperactivity, unusual cataplexy, sleep-related motor issues, and increased anxiety or depression. Case 2 was first misdiagnosed as post-viral hypersomnia, delaying proper evaluation until cataplexy and signs of early puberty appeared. Narcolepsy in children is often linked to obesity and early puberty, both of which should be assessed.16 In this case, early diagnosis and treatment helped stop the progression of pubertal signs, reducing the risk of long-term physical and emotional effects.

In adults, diagnosing narcolepsy can be difficult due to overlapping symptoms with more common sleep disorders. In Case 3, moderate OSA masked the underlying narcolepsy type 2, despite a long history of excessive daytime sleepiness. In adults, comorbidities such as obesity, OSA, and hypertension further complicate diagnosis and treatment.10,17 This case shows how untreated OSA and resistant hypertension can hide or worsen narcoleptic symptoms, requiring careful management of heart risks, CPAP use, and medication.18 OSA is more common in people with narcolepsy, possibly due to orexin deficiency, which can affect hormones, weight, and breathing during sleep.10,19 Only after OSA was controlled with CPAP did persistent sleepiness lead to further testing and a correct diagnosis of narcolepsy.

Overall, these diagnostic scenarios underscore the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for narcolepsy in patients with persistent excessive daytime sleepiness, even in the presence of seemingly adequate alternative explanations. Objective testing and longitudinal clinical observation remain crucial for establishing an accurate diagnosis.

All three cases highlight the significant impact narcolepsy can have on daily life and well-being, regardless of age. In children, it can affect cognitive function, emotional regulation, and social engagement.20,21 Case 1 showed how EDS limited the participation of the patient in after-school activities, caused irritability, and disrupted family life—even though academic performance was unaffected. Case 2 illustrated the developmental effects of narcolepsy, including signs of early puberty. Although not confirmed as true precocious puberty, these symptoms added medical and emotional challenges. It is unclear whether these changes were due to hypothalamic dysfunction from narcolepsy or were unrelated, but the overall symptom burden was substantial for both the child and family.

In adults, narcolepsy presents different challenges.22 Case 3 emphasized the safety risks of untreated hypersomnolence in a bus driver and the emotional toll of poor sleep quality and medication side effects. These difficulties were worsened by comorbid OSA and cardiovascular risk. Together, the cases demonstrate the wide-ranging effects of narcolepsy on functioning and mental health across age groups.

As outlined in European guidelines, treatment in all three narcolepsy cases was personalized and adjusted based on response and tolerability.23 A common need was to optimize dosage and choose medications carefully. In Case 1, a child who did not respond to methylphenidate improved significantly with pitolisant, showing better alertness and daily functioning with few side effects. Case 2 also responded well to pitolisant, with improvements in sleepiness, cataplexy, and stabilization of weight and early puberty—supporting its use when comorbidities limit stimulant options. In Case 3, standard treatments like modafinil and solriamfetol were avoided due to the patient's high cardiovascular risk,24,25 leading to the use of pitolisant. Although initially prescribed at a higher dose, it had to be adjusted due to tolerability issues, which were resolved with a lower dose. These cases suggest pitolisant is a valuable option for both children and adults, especially when stimulants are not suitable.

In conclusion, the three presented cases illustrate the diverse clinical manifestations of narcolepsy across different age groups, emphasizing the diagnostic challenges, the profound impact on quality of life, and the necessity for individualized treatment approaches. Despite varying phenotypes, pitolisant emerged as an effective therapeutic option, demonstrating improvements in excessive daytime sleepiness, cataplexy, and functional outcomes. These findings underscore the importance of early diagnosis, multidisciplinary management, and tailored pharmacotherapy to optimize patient care. Furthermore, the cases highlight the value of real-world clinical data in refining treatment strategies, particularly for complex or treatment-resistant presentations. Future research should continue to explore long-term outcomes, optimal dosing, and the role of newer agents in diverse narcolepsy populations.

Ethical considerations and patient consentThe work described has been carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Given the nature of this study, the project was exempt from institution review board/ethics committee review. Informed consent was obtained from the patients.

FundingThe contest “Abre los Ojos en Narcolepsia” was funded by Bioprojet Pharma and consisted of a web platform.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Writing and editorial assistance was provided by Content Ed Net (Madrid, Spain).