Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is a neurosurgical technique that modulates neural circuits through electrical impulses. Initially developed for motor disorders such as Parkinson's disease, its use has expanded to neuropsychiatric conditions, including treatment-resistant schizophrenia, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and chronic anorexia nervosa, with promising results. However, challenges remain regarding treatment personalization, identification of anatomical targets, and understanding its mechanisms of action.

ObjectiveTo assess the effectiveness, safety, and technical factors associated with DBS in neuropsychiatric disorders through a systematic review of the available scientific literature.

MethodsA systematic review was conducted following PRISMA guidelines. Controlled clinical trials, observational studies, and case series with ≥10 participants were included, covering neuropsychiatric conditions such as OCD, treatment-resistant schizophrenia, and chronic anorexia nervosa. The primary outcomes were changes in clinical scales (e.g., PANSS, Y-BOCS) and adverse events, analyzed using critical appraisal tools such as RoB2 and the Newcastle-Ottawa scale.

ResultsOut of 3351 initial records, 11 studies with 235 participants were included. Significant improvements were observed in specific symptoms: a 40% reduction in motor tics (p < 0.001) in Tourette syndrome, and a 10% increase in body mass index (p = 0.02) in anorexia nervosa. However, the effects on Alzheimer's disease were heterogeneous, showing cognitive decline in patients <65 years (p = 0.006). Adverse events included mild neuropsychological impairment and severe perioperative complications in isolated cases.

DiscussionDBS proves effective in refractory neuropsychiatric disorders, modulating specific symptoms and improving quality of life. Methodological limitations persist in the literature, such as small sample sizes and heterogeneity in stimulation parameters. The need for multicenter studies and biomarkers to predict therapeutic responses is emphasized.

La estimulación cerebral profunda (ECP) es una técnica neuroquirúrgica que modula los circuitos neuronales mediante impulsos eléctricos. Aunque originalmente fue desarrollada para tratar trastornos del movimiento como la enfermedad de Parkinson, posteriormente se ha utilizado en enfermedades neuropsiquiátricas graves, incluyendo la esquizofrenia resistente al tratamiento, el trastorno obsesivo-compulsivo (TOC) y la anorexia nerviosa crónica. A pesar de los resultados clínicos prometedores, persisten desafíos relacionados con la selección de pacientes, la identificación de los mejores blancos de estimulación y la comprensión de los mecanismos de acción.

DesarrolloSe llevó a cabo una revisión sistemática siguiendo las directrices PRISMA, que incluyó ensayos clínicos controlados, estudios observacionales y series de casos con al menos 10 participantes. La revisión se centró en el uso de la ECP en el TOC, la esquizofrenia resistente al tratamiento y la anorexia nerviosa crónica. El resultado primario fue la modulación de los síntomas evaluada mediante escalas clínicas (p. ej., PANSS, Y-BOCS) y el reporte de eventos adversos. Se incluyeron un total de 11 estudios, con 235 pacientes, seleccionados de entre 3351 registros iniciales. La ECP mostró mejoras significativas en los síntomas, incluyendo una reducción del 40% en los tics motores en el síndrome de Tourette (p < 0.001) y un aumento del 10% en el índice de masa corporal en la anorexia nerviosa (p = 0.02). Sin embargo, los resultados en la enfermedad de Alzheimer fueron menos consistentes, observándose deterioro cognitivo solo en pacientes menores de 65 años (p = 0.006). Los efectos adversos variaron desde síntomas cognitivos leves hasta complicaciones quirúrgicas graves, aunque poco frecuentes.

ConclusionesLa ECP puede ser una opción terapéutica eficaz para algunos trastornos neuropsiquiátricos refractarios, al proporcionar alivio sintomático y mejora en la calidad de vida. Sin embargo, se requieren más estudios multicéntricos, comparativos y estandarizados con muestras más amplias para determinar biomarcadores predictivos, la seguridad y la eficacia a largo plazo.

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) has emerged as one of the most significant advancements in the field of functional neurosurgery, redefining the management of multiple neurological and psychiatric disorders. Initially conceived as a treatment for movement disorders, this surgical technique has evolved into a cutting-edge therapeutic approach, also applicable to neuropsychiatric conditions resistant to other treatments.

DBS began as an alternative to ablative surgical procedures, such as thalamotomy and pallidotomy, quickly gaining adoption due to its ability to modulate dysfunctional neural circuits in real time. Since its initial implementation in the 1990s, its most widely documented application has been in Parkinson's disease. In this context, DBS has shown significant improvements in cardinal motor symptoms such as tremors, rigidity, and bradykinesia, comparable to the effects of dopaminergic medications. Nevertheless, it has been established that DBS does not halt disease progression, and its benefits may diminish over time due to the degeneration of non-dopaminergic pathways.1

In advanced Parkinson's patients, DBS has demonstrated long-term benefits, improving quality of life even beyond a decade of follow-up, as indicated by the study by Hitti et al. (2019). Notably, the subthalamic nucleus has been identified as the preferred target due to its efficacy in reducing motor fluctuations and medication-induced dyskinesias.2 Additionally, other nuclei, such as the internal globus pallidus, have shown effectiveness in managing dyskinesias, albeit with differences in side effect profiles and medication adjustments.3

Over recent decades, the use of DBS has expanded to neuropsychiatric conditions, including obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), treatment-resistant major depressive disorder (TRD), and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). These conditions share common features of dysfunction in specific neural networks, such as the prefrontal cortex and nucleus accumbens, suggesting that electrical modulation could restore altered functional patterns.1

Initial studies have reported substantial improvements in patient's refractory to conventional treatments, consolidating DBS as a therapeutic option for patients with severe disorders. For instance, in OCD, stimulation targeting the nucleus accumbens has enabled a reduction in previously uncontrollable obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Similarly, in TRD, DBS has facilitated adaptive restructuring of brain networks involved in emotional regulation (Fig. 1).

The success of DBS lies in its ability to disrupt or modulate dysfunctional neuronal activity. It is hypothesized that electrical stimulation alters neuronal synchronization and oscillatory activity within specific networks, promoting synaptic plasticity and facilitating adaptive reorganization. However, the exact mechanisms remain poorly understood. Recent research has suggested that the therapeutic effects of DBS may involve both immediate functional alterations and long-term plastic changes, but they do not fully account for the variability in efficacy across patients.4

Despite its advancements, DBS implementation faces significant challenges. Precise identification of anatomical targets for each condition remains complex, given that the implicated neural networks can vary considerably between patients and pathologies. While structures such as the subthalamic nucleus, nucleus accumbens, and thalamus have been extensively studied, therapeutic outcomes exhibit high variability.5

Moreover, the literature on DBS is heterogeneous, with studies differing in methodologies, stimulation parameters, and follow-up durations. This limits the generalizability of findings and underscores the need for standardized clinical protocols.3

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) has significantly advanced the treatment of neurological and psychiatric disorders, establishing a landmark in personalized medicine. Despite its success, important knowledge gaps remain, particularly regarding mechanisms of action and treatment variability. Addressing these gaps is vital to fully harness DBS's therapeutic potential and ensure safe, effective use (Table 1).

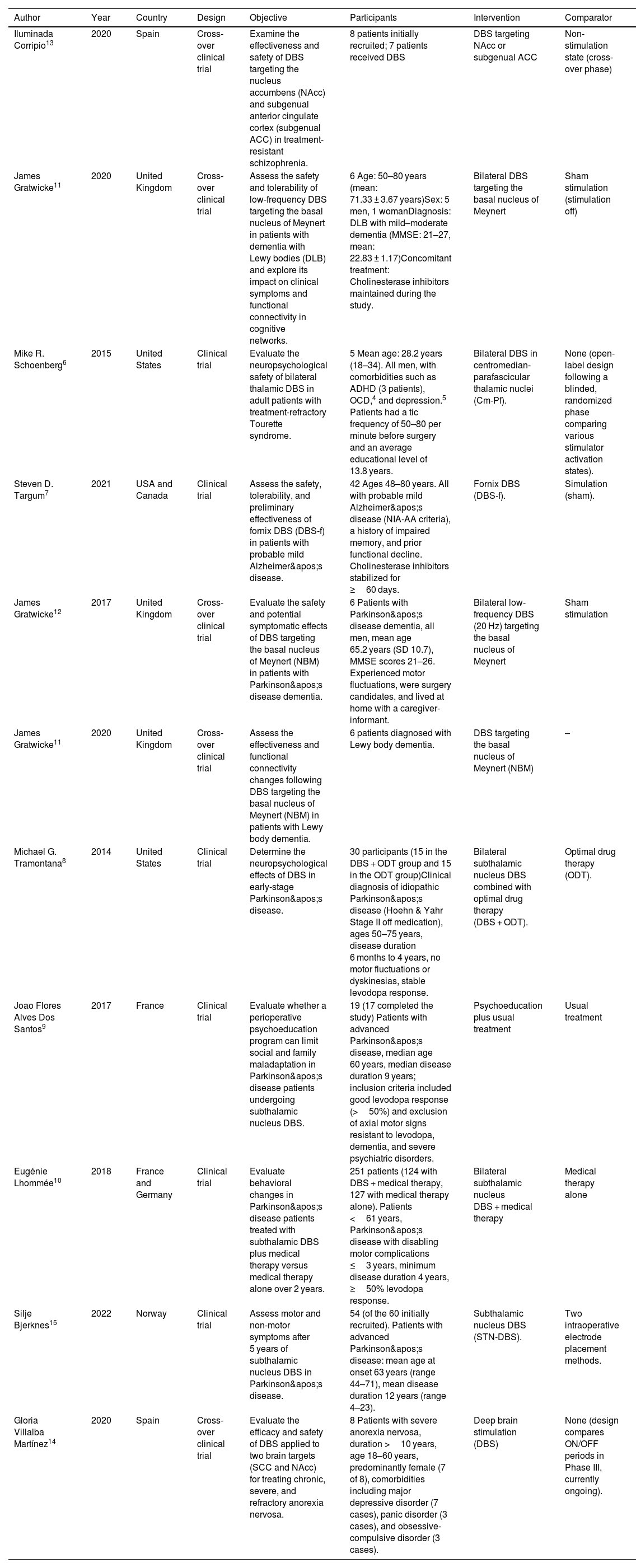

Characteristics of included studies.

| Author | Year | Country | Design | Objective | Participants | Intervention | Comparator |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iluminada Corripio13 | 2020 | Spain | Cross-over clinical trial | Examine the effectiveness and safety of DBS targeting the nucleus accumbens (NAcc) and subgenual anterior cingulate cortex (subgenual ACC) in treatment-resistant schizophrenia. | 8 patients initially recruited; 7 patients received DBS | DBS targeting NAcc or subgenual ACC | Non-stimulation state (cross-over phase) |

| James Gratwicke11 | 2020 | United Kingdom | Cross-over clinical trial | Assess the safety and tolerability of low-frequency DBS targeting the basal nucleus of Meynert in patients with dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and explore its impact on clinical symptoms and functional connectivity in cognitive networks. | 6 Age: 50–80 years (mean: 71.33 ± 3.67 years)Sex: 5 men, 1 womanDiagnosis: DLB with mild–moderate dementia (MMSE: 21–27, mean: 22.83 ± 1.17)Concomitant treatment: Cholinesterase inhibitors maintained during the study. | Bilateral DBS targeting the basal nucleus of Meynert | Sham stimulation (stimulation off) |

| Mike R. Schoenberg6 | 2015 | United States | Clinical trial | Evaluate the neuropsychological safety of bilateral thalamic DBS in adult patients with treatment-refractory Tourette syndrome. | 5 Mean age: 28.2 years (18–34). All men, with comorbidities such as ADHD (3 patients), OCD,4 and depression.5 Patients had a tic frequency of 50–80 per minute before surgery and an average educational level of 13.8 years. | Bilateral DBS in centromedian-parafascicular thalamic nuclei (Cm-Pf). | None (open-label design following a blinded, randomized phase comparing various stimulator activation states). |

| Steven D. Targum7 | 2021 | USA and Canada | Clinical trial | Assess the safety, tolerability, and preliminary effectiveness of fornix DBS (DBS-f) in patients with probable mild Alzheimer's disease. | 42 Ages 48–80 years. All with probable mild Alzheimer's disease (NIA-AA criteria), a history of impaired memory, and prior functional decline. Cholinesterase inhibitors stabilized for ≥60 days. | Fornix DBS (DBS-f). | Simulation (sham). |

| James Gratwicke12 | 2017 | United Kingdom | Cross-over clinical trial | Evaluate the safety and potential symptomatic effects of DBS targeting the basal nucleus of Meynert (NBM) in patients with Parkinson's disease dementia. | 6 Patients with Parkinson's disease dementia, all men, mean age 65.2 years (SD 10.7), MMSE scores 21–26. Experienced motor fluctuations, were surgery candidates, and lived at home with a caregiver-informant. | Bilateral low-frequency DBS (20 Hz) targeting the basal nucleus of Meynert | Sham stimulation |

| James Gratwicke11 | 2020 | United Kingdom | Cross-over clinical trial | Assess the effectiveness and functional connectivity changes following DBS targeting the basal nucleus of Meynert (NBM) in patients with Lewy body dementia. | 6 patients diagnosed with Lewy body dementia. | DBS targeting the basal nucleus of Meynert (NBM) | – |

| Michael G. Tramontana8 | 2014 | United States | Clinical trial | Determine the neuropsychological effects of DBS in early-stage Parkinson's disease. | 30 participants (15 in the DBS + ODT group and 15 in the ODT group)Clinical diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson's disease (Hoehn & Yahr Stage II off medication), ages 50–75 years, disease duration 6 months to 4 years, no motor fluctuations or dyskinesias, stable levodopa response. | Bilateral subthalamic nucleus DBS combined with optimal drug therapy (DBS + ODT). | Optimal drug therapy (ODT). |

| Joao Flores Alves Dos Santos9 | 2017 | France | Clinical trial | Evaluate whether a perioperative psychoeducation program can limit social and family maladaptation in Parkinson's disease patients undergoing subthalamic nucleus DBS. | 19 (17 completed the study) Patients with advanced Parkinson's disease, median age 60 years, median disease duration 9 years; inclusion criteria included good levodopa response (>50%) and exclusion of axial motor signs resistant to levodopa, dementia, and severe psychiatric disorders. | Psychoeducation plus usual treatment | Usual treatment |

| Eugénie Lhommée10 | 2018 | France and Germany | Clinical trial | Evaluate behavioral changes in Parkinson's disease patients treated with subthalamic DBS plus medical therapy versus medical therapy alone over 2 years. | 251 patients (124 with DBS + medical therapy, 127 with medical therapy alone). Patients <61 years, Parkinson's disease with disabling motor complications ≤3 years, minimum disease duration 4 years, ≥50% levodopa response. | Bilateral subthalamic nucleus DBS + medical therapy | Medical therapy alone |

| Silje Bjerknes15 | 2022 | Norway | Clinical trial | Assess motor and non-motor symptoms after 5 years of subthalamic nucleus DBS in Parkinson's disease. | 54 (of the 60 initially recruited). Patients with advanced Parkinson's disease: mean age at onset 63 years (range 44–71), mean disease duration 12 years (range 4–23). | Subthalamic nucleus DBS (STN-DBS). | Two intraoperative electrode placement methods. |

| Gloria Villalba Martínez14 | 2020 | Spain | Cross-over clinical trial | Evaluate the efficacy and safety of DBS applied to two brain targets (SCC and NAcc) for treating chronic, severe, and refractory anorexia nervosa. | 8 Patients with severe anorexia nervosa, duration >10 years, age 18–60 years, predominantly female (7 of 8), comorbidities including major depressive disorder (7 cases), panic disorder (3 cases), and obsessive-compulsive disorder (3 cases). | Deep brain stimulation (DBS) | None (design compares ON/OFF periods in Phase III, currently ongoing). |

This review responds to that need by systematically analyzing the literature to assess the effectiveness and safety of DBS in neuropsychiatric conditions. It also aims to identify technical and clinical factors that may enhance therapeutic outcomes and highlight areas requiring further research.

This review explores key questions: Which neuropsychiatric conditions benefit most from DBS? Which technical factors (e.g., electrode placement, stimulation settings) are critical? What are the main risks and complications?

To answer these, a systematic review was conducted using PRISMA guidelines. It includes clinical studies and meta-analyses evaluating outcomes, technical variables, and adverse events. Both qualitative and quantitative analyses aim to clarify current knowledge and guide future research and clinical practice in DBS for neuropsychiatric disorders (Table 2).

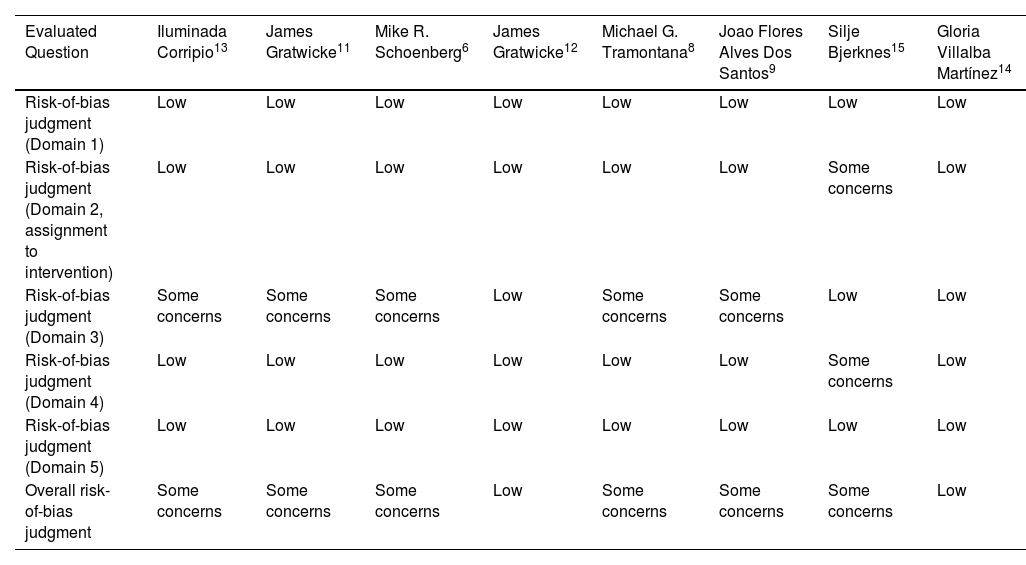

Risk of bias assessment of included studies.

| Evaluated Question | Iluminada Corripio13 | James Gratwicke11 | Mike R. Schoenberg6 | James Gratwicke12 | Michael G. Tramontana8 | Joao Flores Alves Dos Santos9 | Silje Bjerknes15 | Gloria Villalba Martínez14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk-of-bias judgment (Domain 1) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Risk-of-bias judgment (Domain 2, assignment to intervention) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Some concerns | Low |

| Risk-of-bias judgment (Domain 3) | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low | Low |

| Risk-of-bias judgment (Domain 4) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Some concerns | Low |

| Risk-of-bias judgment (Domain 5) | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Overall risk-of-bias judgment | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low | Some concerns | Some concerns | Some concerns | Low |

A systematic review of primary studies was conducted, following the guidelines outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Observational and experimental studies analyzing the effectiveness and safety of deep brain stimulation (DBS) in neuropsychiatric disorders were included.

Selection criteriaTypes of studiesRandomized controlled trials (RCTs), observational studies (cohort and case–control designs), and case series with at least 10 participants were included. Narrative reviews, expert opinions, and articles without primary data were excluded.

Types of participantsAdult patients diagnosed with neuropsychiatric disorders such as treatment-resistant schizophrenia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, severe addictions, or Tourette syndrome. No restrictions were applied regarding sex, ethnicity, or associated comorbidities.

Types of interventionsThe primary intervention was DBS applied to specific brain nuclei. Comparators included “off” stimulation (sham), placebo, or standard treatments.

Types of outcomesPrimary outcomes included changes in clinical scales (e.g., PANSS, Y-BOCS, HAM-A, HAM-D) and the rate of severe adverse events related to DBS. Secondary outcomes included quality of life, measures of functional brain connectivity, cognitive changes, and craving reduction.

Search methods for study identificationElectronic searchesSearches were conducted in databases such as MEDLINE, EMBASE, CENTRAL, PsycINFO, and LILACS. Strategies were designed using both controlled vocabulary and free-text terms to capture variations in terminology.

Other resourcesReferences from included studies, clinical trial registries, and proceedings from specialized conferences were reviewed. Unpublished studies were also sought in gray literature registries.

Data collection and analysisStudy selectionTwo independent reviewers assessed titles, abstracts, and full texts. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or consultation with a third reviewer.

Data extraction and managementA standardized form was used to collect information on study characteristics, participants, interventions, outcomes, and results. Data were cross-verified by two reviewers.

Critical appraisal of included studiesThe risk of bias in RCTs was assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool (RoB2), while observational studies were evaluated with the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, considering biases in selection, measurement, and comparability (Table 3).

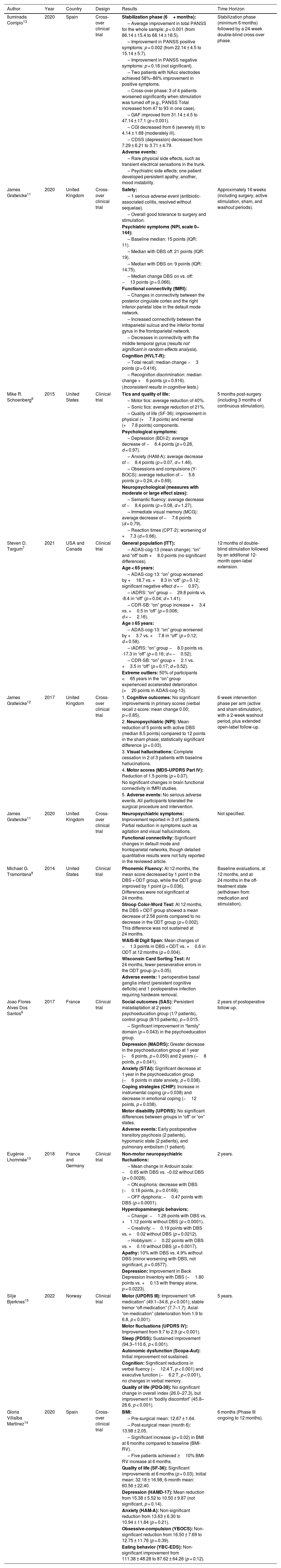

Results of Included Studies.

| Author | Year | Country | Design | Results | Time Horizon |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iluminada Corripio13 | 2020 | Spain | Cross-over clinical trial | Stabilization phase (6+ months): | Stabilization phase (minimum 6 months) followed by a 24-week double-blind cross-over phase. |

| – Average improvement in total PANSS for the whole sample: p < 0.001 (from 86.14 ± 15.4 to 68.14 ± 18.5). | |||||

| – Improvement in PANSS positive symptoms: p = 0.002 (from 22.14 ± 4.5 to 15.14 ± 5.7). | |||||

| – Improvement in PANSS negative symptoms: p = 0.18 (not significant). | |||||

| – Two patients with NAcc electrodes achieved 58%–86% improvement in positive symptoms. | |||||

| – Cross-over phase: 3 of 4 patients worsened significantly when stimulation was turned off (e.g., PANSS Total increased from 47 to 93 in one case). | |||||

| – GAF improved from 31.14 ± 4.5 to 47.14 ± 17.1 (p < 0.001). | |||||

| – CGI decreased from 6 (severely ill) to 4.14 ± 1.68 (moderately ill). | |||||

| – CDSS (depression) decreased from 7.29 ± 6.21 to 3.71 ± 4.79. | |||||

| Adverse events: | |||||

| – Rare physical side effects, such as transient electrical sensations in the trunk. | |||||

| – Psychiatric side effects: one patient developed persistent apathy; another, mood instability. | |||||

| James Gratwicke11 | 2020 | United Kingdom | Cross-over clinical trial | Safety: | Approximately 16 weeks (including surgery, active stimulation, sham, and washout periods). |

| – 1 serious adverse event (antibiotic-associated colitis, resolved without sequelae). | |||||

| – Overall good tolerance to surgery and stimulation. | |||||

| Psychiatric symptoms (NPI, scale 0–144): | |||||

| – Baseline median: 15 points (IQR: 11). | |||||

| – Median with DBS off: 21 points (IQR: 19). | |||||

| – Median with DBS on: 9 points (IQR: 14.75). | |||||

| – Median change DBS on vs. off: −13 points (p = 0.066). | |||||

| Functional connectivity (fMRI): | |||||

| – Changes in connectivity between the posterior cingulate cortex and the right inferior parietal lobe in the default mode network. | |||||

| – Increased connectivity between the intraparietal sulcus and the inferior frontal gyrus in the frontoparietal network. | |||||

| – Decreases in connectivity with the middle temporal gyrus (results not significant in random effects analysis). | |||||

| Cognition (HVLT-R): | |||||

| – Total recall: median change −3 points (p = 0.416). | |||||

| – Recognition discrimination: median change +6 points (p = 0.916). | |||||

| (Inconsistent results in cognitive tests.) | |||||

| Mike R. Schoenberg6 | 2015 | United States | Clinical trial | Tics and quality of life: | 5 months post-surgery (including 3 months of continuous stimulation). |

| – Motor tics: average reduction of 40%. | |||||

| – Sonic tics: average reduction of 21%. | |||||

| – Quality of life (SF-36): improvement in physical (+7.8 points) and mental (+7.8 points) components. | |||||

| Psychological symptoms: | |||||

| – Depression (BDI-2): average decrease of −6.4 points (p = 0.28, d = 0.97). | |||||

| – Anxiety (HAM-A): average decrease of −8.4 points (p = 0.07, d = 1.46). | |||||

| – Obsessions and compulsions (Y-BOCS): average reduction of −5.6 points (p = 0.24, d = 0.69). | |||||

| Neuropsychological (measures with moderate or large effect sizes): | |||||

| – Semantic fluency: average decrease of −8.4 points (p = 0.08, d = 1.27). | |||||

| – Immediate visual memory (MCG): average decrease of −7.6 points (d = 0.79). | |||||

| – Reaction times (CPT-2): worsening of +7.3 (d = 0.66). | |||||

| Steven D. Targum7 | 2021 | USA and Canada | Clinical trial | General population (ITT): | 12 months of double-blind stimulation followed by an additional 12-month open-label extension. |

| – ADAS-cog-13 (mean change): “on” and “off” both +8.0 points (no significant differences). | |||||

| Age < 65 years: | |||||

| – ADAS-cog-13: “on” group worsened by +18.7 vs. +8.3 in “off” (p = 0.12; significant negative effect d = −0.97). | |||||

| – iADRS: “on” group −29.8 points vs. -8.4 in “off” (p = 0.04; d = 1.41). | |||||

| – CDR-SB: “on” group increase +3.4 vs. +0.5 in “off” (p = 0.006; d = −2.16). | |||||

| Age ≥ 65 years: | |||||

| – ADAS-cog-13: “on” group worsened by +3.7 vs. +7.8 in “off” (p = 0.12; d = 0.58). | |||||

| – iADRS: “on” group −8.0 points vs. -17.3 in “off” (p = 0.16; d = −0.52). | |||||

| – CDR-SB: “on” group +2.1 vs. +3.5 in “off” (p = 0.17; d = 0.52). | |||||

| Extreme outliers: 50% of participants <65 years in the “on” group experienced accelerated deterioration (>20 points in ADAS-cog-13). | |||||

| James Gratwicke12 | 2017 | United Kingdom | Cross-over clinical trial | 1. Cognitive outcomes: No significant improvements in primary scores (verbal recall z-score: mean change 0.00; p = 0.85). | 6-week intervention phase per arm (active and sham stimulation), with a 2-week washout period, plus extended open-label follow-up. |

| 2. Neuropsychiatric (NPI): Mean reduction of 5 points with active DBS (median 8.5 points) compared to 12 points in the sham phase; statistically significant difference (p = 0.03). | |||||

| 3. Visual hallucinations: Complete cessation in 2 of 3 patients with baseline hallucinations. | |||||

| 4. Motor scores (MDS-UPDRS Part IV): Reduction of 1.5 points (p = 0.07). | |||||

| No significant changes in brain functional connectivity in fMRI studies. | |||||

| 5. Adverse events: No serious adverse events. All participants tolerated the surgical procedure and intervention. | |||||

| James Gratwicke11 | 2020 | United Kingdom | Cross-over clinical trial | Neuropsychiatric symptoms: Improvement reported in 3 of 5 patients. Partial reduction in symptoms such as agitation and visual hallucinations. | Not specified. |

| Functional connectivity: Significant changes in default mode and frontoparietal networks, though detailed quantitative results were not fully reported in the reviewed article. | |||||

| Michael G. Tramontana8 | 2014 | United States | Clinical trial | Phonemic Fluency: At 12 months, the mean score decreased by 1 point in the DBS + ODT group, while the ODT group improved by 1 point (p = 0.036). Differences were not significant at 24 months. | Baseline evaluations, at 12 months, and at 24 months in the off-treatment state (withdrawn from medication and stimulation). |

| Stroop Color-Word Test: At 12 months, the DBS + ODT group showed a mean decrease of 2.58 points compared to no decrease in the ODT group (p = 0.002). This difference was not sustained at 24 months. | |||||

| WAIS-III Digit Span: Mean changes of −1.3 points in DBS + ODT vs. +0.6 in ODT at 12 months (p = 0.004). | |||||

| Wisconsin Card Sorting Test: At 24 months, fewer perseverative errors in the ODT group (p = 0.05). | |||||

| Adverse events: 1 perioperative basal ganglia infarct (persistent cognitive deficits) and 1 postoperative infection requiring hardware removal. | |||||

| Joao Flores Alves Dos Santos9 | 2017 | France | Clinical trial | Social outcomes (SAS): Persistent maladaptation at 2 years: psychoeducation group (1/7 patients), control group (8/10 patients), p = 0.015. | 2 years of postoperative follow-up. |

| – Significant improvement in “family” domain (p = 0.043) in the psychoeducation group. | |||||

| Depression (MADRS): Greater decrease in the psychoeducation group at 1 year (−6 points, p = 0.050) and 2 years (−8 points, p = 0.041). | |||||

| Anxiety (STAI): Significant decrease at 1 year in the psychoeducation group (−6 points in state anxiety, p = 0.038). | |||||

| Coping strategies (CHIP): Increase in instrumental coping (p = 0.038) and decrease in emotional coping (−12 points, p = 0.038). | |||||

| Motor disability (UPDRS): No significant differences between groups in “off” or “on” states. | |||||

| Adverse events: Early postoperative transitory psychosis (2 patients), hypomanic state (2 patients), and pulmonary embolism (1 patient). | |||||

| Eugénie Lhommée10 | 2018 | France and Germany | Clinical trial | Non-motor neuropsychiatric fluctuations: | 2 years. |

| – Mean change in Ardouin scale: −0.65 with DBS vs. −0.02 without DBS (p = 0.0028). | |||||

| – ON euphoria: decrease with DBS (−0.18 points, p = 0.0169). | |||||

| – OFF dysphoria: −0.47 points with DBS (p = 0.0001). | |||||

| Hyperdopaminergic behaviors: | |||||

| – Change: −1.26 points with DBS vs. +1.12 points without DBS (p < 0.0001). | |||||

| – Creativity: −0.19 points with DBS vs. +0.02 without DBS (p = 0.0212). | |||||

| – Hobbyism: −0.22 points with DBS vs. +0.10 without DBS (p = 0.0017). | |||||

| Apathy: 10% with DBS vs. 4.9% without DBS (minor worsening with DBS, not significant, p = 0.0577). | |||||

| Depression: Improvement in Beck Depression Inventory with DBS (−1.80 points vs. +0.13 with therapy alone, p = 0.0223). | |||||

| Silje Bjerknes15 | 2022 | Norway | Clinical trial | Motor (UPDRS III): Improvement “off-medication” (49.1–34.8, p < 0.001); stable tremor “off-medication” (7.7–1.7). Axial “on-medication” (deterioration from 1.9 to 6.8, p < 0.001). | 5 years. |

| Motor fluctuations (UPDRS IV): Improvement from 9.7 to 2.9 (p < 0.001). | |||||

| Sleep (PDSS): Sustained improvement (94.3–110.6, p < 0.001). | |||||

| Autonomic dysfunction (Scopa-Aut): Initial improvement not sustained. | |||||

| Cognition: Significant reductions in verbal fluency (−12.4 T, p < 0.001) and executive function (−6.2 T, p < 0.001), no changes in verbal memory. | |||||

| Quality of life (PDQ-39): No significant change in overall index (26.0–27.3), but improvement in “bodily discomfort” (45.8–28.6, p < 0.001). | |||||

| Gloria Villalba Martínez14 | 2020 | Spain | Cross-over clinical trial | BMI: | 6 months (Phase III ongoing to 12 months). |

| – Pre-surgical mean: 12.67 ± 1.64. | |||||

| – Post-surgical mean (month 6): 13.98 ± 2.05. | |||||

| – Significant increase (p = 0.02) in BMI at 6 months compared to baseline (BMI-RV). | |||||

| – Five patients achieved ≥10% BMI-RV increase at 6 months. | |||||

| Quality of life (SF-36): Significant improvements at 6 months (p = 0.03). Initial mean: 32.18 ± 16.98; 6-month mean: 60.56 ± 22.40. | |||||

| Depression (HAMD-17): Mean reduction from 15.38 ± 5.52 to 10.50 ± 9.87 (not significant, p = 0.14). | |||||

| Anxiety (HAM-A): Non-significant reduction from 13.63 ± 6.30 to 10.94 ± 11.84 (p = 0.21). | |||||

| Obsessive-compulsion (YBOCS): Non-significant reduction from 16.50 ± 7.69 to 12.75 ± 11.76 (p = 0.39). | |||||

| Eating behavior (YBC-EDS): Non-significant improvement from 111.38 ± 48.28 to 87.62 ± 64.26 (p = 0.12). | |||||

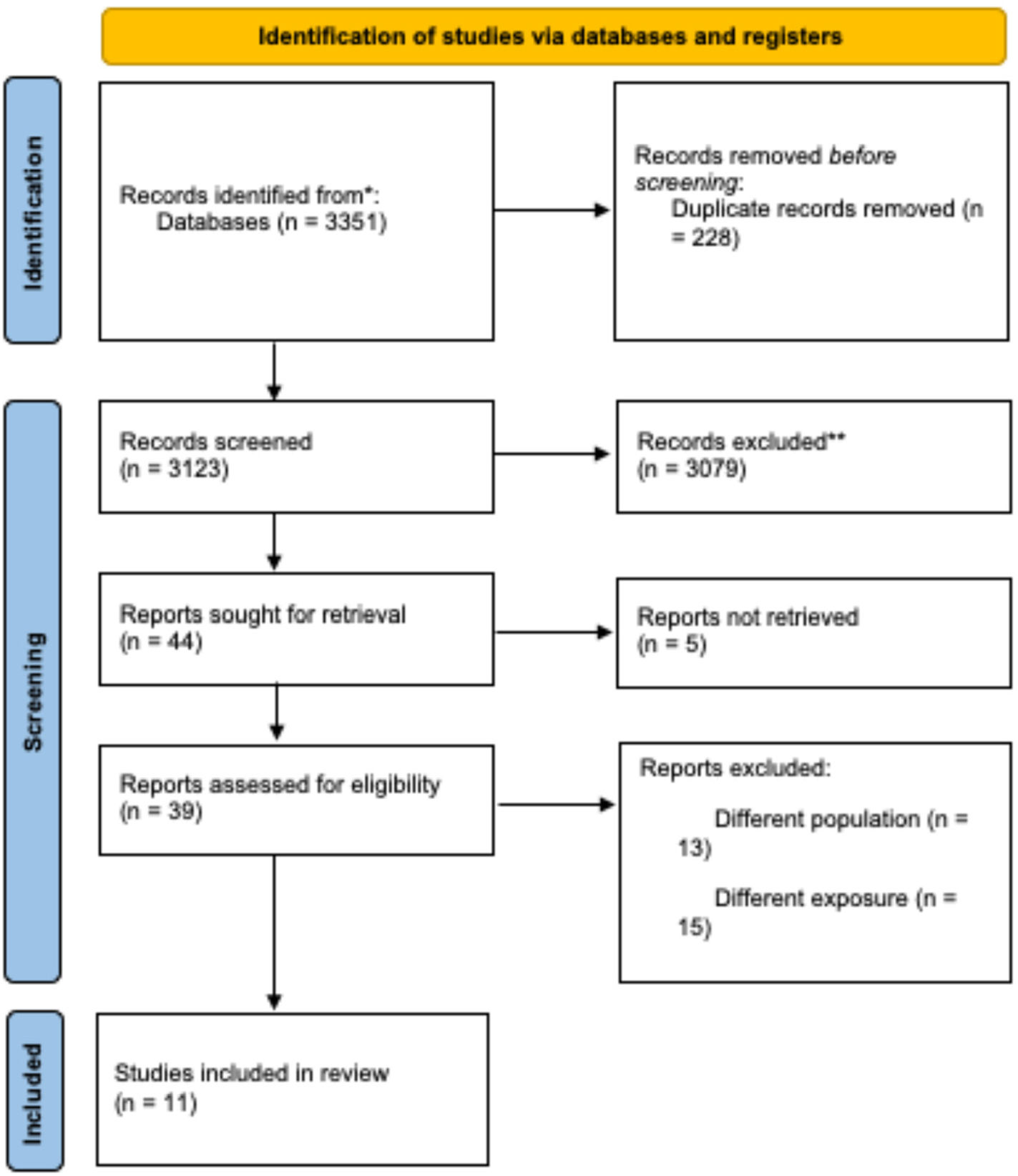

During the initial identification phase, 3351 records were retrieved from databases and registries. After removing duplicates, 3123 unique records remained for evaluation. During the screening process, 3079 records were excluded based on title and abstract review, resulting in 39 studies assessed in full text. Ultimately, 11 studies were included in the systematic review.

Study characteristicsThe 11 studies included a total of 235 participants and were conducted in various countries: three in the United States,6–8 two in France,9,10 two in the United Kingdom,11,12 two in Spain,13,14 one in Norway,15 and one with collaboration between France and Germany.10

The study designs included clinical trials (n = 8) and crossover trials (n = 3). The interventions evaluated were primarily deep-brain stimulation (DBS) applied to different brain areas, including the basal nucleus of Meynert, subthalamic nucleus, nucleus accumbens, subgenual anterior cingulate cortex, and fornix.

ParticipantsThe studies included adults with various neuropsychiatric conditions, such as treatment-resistant schizophrenia, Parkinson's disease dementia, Lewy body dementia, mild Alzheimer's disease, refractory Tourette syndrome, advanced Parkinson's disease, and severe chronic anorexia nervosa. Most studies included between 5 and 54 participants, with mean ages ranging from 18 to 80 years. Participant characteristics often included refractory diseases and specific inclusion criteria such as minimum disease duration, response to levodopa in Parkinson's patients, or standardized diagnostic criteria.

InterventionsThe primary intervention in all studies was DBS, applied bilaterally to different brain regions depending on the disease and study objectives. In some cases, interventions included combinations with optimal medical treatments, pharmacological therapy, or perioperative psychoeducation programs.

ComparatorsComparators included sham stimulation in most crossover studies, no-stimulation states, optimal medical treatments, or no additional intervention in some trials. One study also included a comparison of intraoperative methods for electrode placement.

OutcomesThe systematic review addressed the safety, tolerability, and effectiveness of DBS in various neuropsychiatric diseases. The studies reported a wide range of specific objectives, including the assessment of clinical symptoms, changes in functional connectivity, and neuropsychological and behavioral effects following intervention. For a more detailed description of each study, see the supplementary material.

Risk of bias assessmentNine studies were evaluated for risk of bias using a domain-based approach.

Domains assessed- •

Domain 1 (risk of bias in question generation): All studies were classified as low risk.

- •

Domain 2 (allocation to intervention): Most studies (8 out of 9) were classified as low risk, with one study presenting “some concerns.”

- •

Domain 3 (risk of bias in measurement): Five studies presented “some concerns” in this domain, while the rest were considered low risk.

- •

Domain 4 (risk of bias in intervention execution): Eight studies were classified as low risk, with one presenting “some concerns.”

- •

Domain 5 (risk of bias in results): All studies were classified as low risk.

Three studies were considered low risk overall, while six studies presented “some concerns” in the general evaluation. These concerns reflect limitations in specific domains, primarily in outcome measurement and intervention execution in certain studies.

Study resultsThis systematic review included various studies evaluating deep brain stimulation (DBS) in different neuropsychiatric disorders, each reporting specific results based on their design and temporal horizon.

In the study by Iluminada Corripio (2020, Spain),13 significant improvements were observed in positive PANSS symptoms and global functioning (GAF), though no significant changes were noted in negative symptoms. During the crossover phase, cessation of stimulation resulted in worsening symptoms in three out of four patients. Conversely, James Gratwicke (2020, United Kingdom)11 reported trends toward improvements in neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with Lewy body dementia, though these did not reach statistical significance. Changes in functional brain connectivity were also observed, albeit inconclusively.

In the study by Mike R. Schoenberg (2015, United States),6 DBS demonstrated reductions in motor and vocal tics in patients with refractory Tourette syndrome, as well as improvements in quality of life and psychological symptoms, though some of these improvements were not statistically significant.

In the context of Alzheimer's disease, Steven D. Targum (2021, United States and Canada)7 observed age-differentiated effects. In patients under 65 years, stimulation resulted in accelerated cognitive and functional decline, whereas those over 65 years showed more favorable outcomes. In another study by James Gratwicke (2017, United Kingdom),12 significant reductions in neuropsychiatric symptoms and cessation of visual hallucinations were noted in patients with Parkinson's disease dementia, although no significant changes in functional brain connectivity were observed.

Michael G. Tramontana (2014, United States)8 reported deficits in neuropsychological tests at 12 months in patients with early Parkinson's disease treated with DBS and pharmacological therapy; however, these deficits did not persist at 24 months. This study also reported severe adverse events, including a perioperative stroke.

Joao Flores Alves Dos Santos (2017, France)9 evaluated a psychoeducation program in advanced Parkinson's disease patients undergoing DBS, observing significant reductions in social maladaptation, depression, and anxiety, alongside improvements in coping strategies. Eugénie Lhommée (2018, France and Germany)10 found that DBS reduced non-motor neuropsychiatric fluctuations and hyperdopaminergic-related symptoms in Parkinson's patients, although a slight, statistically insignificant increase in apathy was noted.

In the study by Silje Bjerknes (2022, Norway),15 DBS targeting the subthalamic nucleus significantly improved “off-medication” motor symptoms and sleep quality, though verbal fluency and executive function deteriorated.

Finally, Gloria Villalba Martínez (2020, Spain)14 evaluated DBS in chronic anorexia nervosa patients, finding a significant increase in body mass index and improvements in quality of life, though reductions in depression, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive behaviors did not reach statistical significance.

The temporal horizons of the studies ranged from 5 months to 5 years, depending on the specific objectives and designs of each investigation.

DiscussionThis systematic review evaluated the effectiveness and safety of deep brain stimulation (DBS) in the treatment of various neuropsychiatric disorders, including treatment-resistant schizophrenia, Parkinson's disease dementia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and chronic anorexia nervosa. Overall, the findings suggest that DBS can be effective in reducing specific clinical symptoms, improving quality of life, and modulating dysfunctional neural networks, although variability exists in outcomes and the occurrence of adverse events. The evidence also highlights differences in efficacy depending on factors such as age, pathology, and technical parameters employed.

DBS has demonstrated efficacy as an intervention for various refractory neurological and psychiatric disorders. Recent findings support the clinical benefits observed in earlier studies, emphasizing its potential to improve specific symptoms and patient quality of life, although challenges persist regarding side effects and variability in results.

Recent studies have documented that DBS targeting regions such as the nucleus accumbens and subgenual anterior cingulate cortex can significantly improve positive symptoms of schizophrenia, as assessed by the PANSS scale. These improvements, along with increased quality of life, establish DBS as a promising therapeutic option for refractory cases.16

In patients with advanced Parkinson's disease, DBS targeting the subthalamic nucleus is considered the standard of care, providing significant improvements in “off-medication” motor symptoms and sleep quality. This approach allows for reduced dosages of levodopa and other dopaminergic therapies while maintaining long-term benefits in quality of life.5,17

Despite its benefits, DBS in the subthalamic nucleus can produce neuropsychological adverse effects, such as reductions in verbal fluency and executive function. Although these effects are generally transient, they require attention and treatment adjustments to minimize their impact on patients.18,19

For patients with Alzheimer's disease, DBS outcomes are mixed. While patients over 65 years may experience modest benefits in slowing cognitive decline, younger patients have shown adverse effects, including accelerated cognitive deterioration. This underscores the need for more targeted studies and personalization of stimulation parameters.20,21

The lack of consistency in clinical study designs, including variability in stimulation parameters and functional brain connectivity measures, limits the generalizability of findings. This reinforces the need for standardized methodological approaches to more accurately evaluate DBS efficacy across different clinical contexts.22

A major limitation of this review is the heterogeneity of included studies in terms of design, sample sizes, and stimulation parameters. Most studies had small sample sizes (n < 50), limiting the generalizability of findings. Additionally, variability in reported outcomes and the lack of long-term follow-up in some studies reduce the ability to draw robust conclusions. However, this review was strengthened by the use of strict inclusion criteria and bias assessment, ensuring a rigorous and representative synthesis of the existing literature. The use of tools such as RoB2 and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale to assess study quality adds validity to the findings.

The results of this review highlight the potential of DBS as a personalized therapeutic intervention for refractory neuropsychiatric disorders, particularly when conventional strategies have failed. However, optimizing clinical protocols through the development of evidence-based guidelines is crucial, with considerations for patient selection, anatomical targets, and stimulation parameters.

From a research perspective, future studies should focus on understanding the neuronal mechanisms underlying DBS and identifying biomarkers to predict clinical response. Additionally, multicenter trials with larger samples and longer follow-up durations are needed to validate these preliminary findings.

ConclusionThis systematic review reaffirms the role of deep brain stimulation as a promising tool for the treatment of refractory neuropsychiatric disorders. While the results are encouraging, significant knowledge gaps remain regarding treatment personalization and the mechanisms of DBS. Addressing these areas through well-designed research will be essential to maximize its therapeutic impact and broaden its application in clinical practice.

Patient consentNot applicable. This study is a systematic review of previously published literature and did not involve direct patient participation or the use of personally identifiable information. Therefore, informed consent was not required.

Ethical considerationsThis study is a systematic literature review and did not involve research with human or animal subjects conducted by the authors. Therefore, it was not necessary to obtain ethics committee approval or informed consent. However, high ethical standards have been maintained in the selection, analysis, and interpretation of the data presented in this study in line with the principles set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki and with the PRISMA reporting guidelines for systematic reviews.

In all the included primary studies that were part of this review, the authors of the primary studies reported hashing out institutional ethics approval as well as appropriate informed consent guidelines for their participants.

FundingThe authors declare that they received no specific financial support from public sector agencies, commercial sector, or not-for-profit entities for the conduct of this systematic review.

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal conflicts of interest that could have inappropriately influenced the conduct or interpretation of the results presented in this article.