Parkinson's disease (PD), a prevalent neurodegenerative disorder characterized by motor dysfunction, presents a significant therapeutic challenge due to the lack of disease-modifying treatments. Emerging evidence suggests a crucial role of the gut microbiota in PD pathogenesis, particularly through its influence on the gut-brain axis.

DevelopmentThe gut-brain axis, a bidirectional communication network involving neural, hormonal, and immune pathways, appears to be significantly modulated by the gut microbiota. Dysbiosis, an imbalance in gut microbial composition, has been implicated in PD progression. Metabolites produced by gut bacteria, such as short-chain fatty acids, are key mediators of gut-brain signaling and may contribute to PD pathogenesis. Preclinical studies utilizing animal models of PD have demonstrated the neuroprotective potential of probiotics, live microorganisms that confer health benefits to the host. These studies report improvements in motor symptoms, reduced neuroinflammation, decreased oxidative stress, and restoration of gut and blood–brain barrier integrity following probiotic administration.

ConclusionsWhile the precise mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of probiotics in PD require further investigation, these interventions hold promise for disease management. Further research is warranted to elucidate the therapeutic potential of probiotics in PD and to develop targeted interventions for modulating the gut microbiota to improve clinical outcomes.

La enfermedad de Parkinson (EP), un trastorno neurodegenerativo prevalente caracterizado por disfunción motora, presenta un desafío terapéutico significativo debido a la falta de tratamientos modificadores de la enfermedad. Nuevas evidencias sugieren un papel crucial de la microbiota intestinal en la patogénesis de la EP, en particular a través de su influencia en el eje intestino-cerebro.

DesarrolloEl eje intestino-cerebro, una red de comunicación bidireccional que involucra vías neuronales, hormonales e inmunitarias, parece estar significativamente modulado por la microbiota intestinal. La disbiosis, un desequilibrio en la composición microbiana intestinal, se ha relacionado con la progresión de la EP. Los metabolitos producidos por las bacterias intestinales, como los ácidos grasos de cadena corta, son mediadores clave de la señalización intestino-cerebro y podrían contribuir a la patogénesis de la EP. Estudios preclínicos con modelos animales de EP han demostrado el potencial neuroprotector de los probióticos, microorganismos vivos que aportan beneficios para la salud del huésped. Estos estudios indican mejoras en los síntomas motores, reducción de la neuroinflamación, disminución del estrés oxidativo y restauración de la integridad de la barrera hematoencefálica e intestinal tras la administración de probióticos.

ConclusionesSi bien los mecanismos precisos que subyacen a los efectos beneficiosos de los probióticos en la EP requieren mayor investigación, estas intervenciones son prometedoras para el manejo de la enfermedad. Se justifican más investigaciones para dilucidar el potencial terapéutico de los probióticos en la EP y desarrollar intervenciones específicas para modular la microbiota intestinal y mejorar los resultados clínicos.

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that predominantly affects individuals aged 60 and above, with an estimated prevalence of approximately 1%.1 While less than 10% of PD cases are attributed to inherited genetic factors, the majority are considered idiopathic or sporadic, suggesting the involvement of other influential elements such as aging and environmental factors in disease development.2

The pathophysiology of PD is characterized by the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the Substantia Nigra pars compacta (SNpc), leading to a reduction of dopamine (DA) levels in the striatum (STR) and the presence of intracellular aggregates known as Lewy bodies, primarily composed of alpha-synuclein (α-syn).3 The reduction in DA levels manifests in motor symptoms including bradykinesia, muscular rigidity, resting tremors, akinesia, hypokinesia, and postural instability.4 Unfortunately, by the time PD is diagnosed based on these motor symptoms, irreversible loss of dopaminergic neurons in the SNpc, ranging from 60% to 80%, has typically occurred.5

The reduction in DA levels in the STR results in notable inhibition of the direct pathway and a significant increase in the indirect pathway. These changes lead to increased inhibitory impulses from the pars reticulata of the Substantia Nigra and the medial part of the globus pallidus to the thalamus, consequently reducing excitation in the motor cortex. These alterations contribute to negative motor signs of PD, such as difficulty in movement accompanied by increased muscle tone.6

Individuals with PD often experience a prodromal phase characterized by nonmotor symptoms that develop gradually for years before the onset of movement-related manifestations. These non-motor symptoms, often underreported unless specifically investigated, include rapid eye movement sleep disorders, depression, anxiety, loss of smell, gastrointestinal disorders, urinary dysfunction, orthostatic hypotension, and excessive daytime sleepiness.7 Notably, constipation, affecting up to 80% of PD patients, can precede motor symptoms for a considerable duration.8

The loss of dopaminergic neurons in PD is associated with neuronal inclusions known as Lewy bodies, primarily composed by insoluble aggregates of the protein α-syn.9,10 Various factors contributed to abnormal α-syn aggregation, including genetic mutations (A30P, E43K and A53T genes), environmental factors (pesticides, metal ions) and mitochondrial dysfunction —which causes cellular damage that can lead to apoptosis of dopaminergic neurons of the SNpc—. Mutations in PINK1 and Parkin genes, important for mitochondrial regulation, may also play a role in PD pathogenesis.11–13

Although α-syn aggregation in the SNpc is a hallmark of PD, it also occurs peripherally. This recent evidence supports the Braak hypothesis, which claims that PD may originate in the gut and after progress to the brain,9,14,15 this also would explain the high prevalence of gastrointestinal affections during the prodromic phase of PD. Clinical and histopathological studies suggest the intestine's crucial role in the development of PD, with constipation being a prevalent and early non-motor symptom estimated to be up to six times higher in PD patients compared to age and gender-matched controls.16 Furthermore, a study based on a national population database demonstrated that the severity of constipation, quantified by laxative use, is dose-dependently correlated with the future risk of PD, independent of factors such as age, gender, comorbidities or medication.17

Preclinical studies administering gastrointestinal injections of preformed α-syn fibrils in animal models have also supported the Braak hypothesis, demonstrating persistent gut-to-brain spread of α-syn, with measurements taken at 1,3,7, and 10 months post-injection, and α-syn spread was prevented by vagotomy. The effects were evident in terms of neurodegeneration and various symptoms (motor, cognitive, psychiatric, olfactory, and gastric dysfunction) consistently manifested over time.18

Subsequent research suggests that altered gut microbiota may contribute to PD development,19 while the gut-brain axis —a bidirectional communication system between the gut and the CNS — has become an area of research of great relevance in relation to PD.20 This review aims to explore recent studies on the association between gut microbiota, the gut-brain axis, and PD, with a focus on the potential of probiotic therapy in disease management.

Gut-brain axis: Understanding the link between the digestive system and the brain in Parkinson's diseaseExperimental studies have highlighted the intricated communication pathways between the gastrointestinal system and the Central Nervous System (CNS), mediated by endocrine, metabolic, immune, and neuronal pathways.

The gastrointestinal tract is recognized as a rich source of nutrients that enable the colonization of bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes. This environment is known as the intestinal or gut microbiota, which influences various metabolic, immune, inflammatory, and barrier integrity-related processes and diseases.21

Alterations in the intestinal microbiota can lead to reduced levels of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), increased inflammation and oxidative stress, and dysregulation of DA and serotonin synthesis,22,23 resulting in gastrointestinal symptoms like constipation, swallowing problems and delayed gastric emptying.24

Studies on Parkinson's disease induction models have demonstrated that intestinal inflammation can compromise both the intestinal and Blood–Brain Barrier (BBB) integrity, contributing to dopaminergic neuron loss in the SNpc.25 In PD patients with intestinal inflammation, increased proinflammatory cytokine expression in the ascending colon has been observed.26 This elevation in inflammatory marker levels correlated with an increase in glial marker production. Studies conducted by Houser et al. (2018) showed an increase in the expression of angiogenesis markers, chemokines, and proinflammatory cytokines in fecal samples from PD patients.27 Increased expression of fecal calprotectin (a marker of intestinal permeability) in PD patients correlates with inflammatory processes observed in colon biopsiesin the same way as in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).28 Furthermore, epidemiological data indicate a link between IBD and PD.29,30

Multiple experimental and clinical evidence demonstrate that intestinal dysbiosis generates inflammation through metabolites of pathogenic bacteria, altering the permeability of the intestinal barrier and contributing to the genesis of PD. The intestinal barrier, which regulates the passage of nutrients and minerals, consists of a mucus layer that houses the microbiota, a layer of immunoglobulins protecting the host from toxins and environmental pathogens, and it is further controlled by tight junctions between enterocytes.31 Disruption of this barrier, termed “Leaky Gut Syndrome”, allows passage of pathogenic bacteria-derived metabolites into the bloodstream, exacerbating inflammatory and oxidative responses seen in PD pathogenesis, like increased α-syn deposition,32,33 modifications in microbiota composition, and decreased tight junction protein expression.34–36

From a pathological perspective, intestinal dysbiosis is proposed to influence gastrointestinal permeability, triggering inflammatory and oxidative responses characteristic of PD and potentially initiating disease onset (with the formation of Lewy bodies) within the enteric nervous system, spreading via the vagus nerve to the brain. The increase in intestinal barrier permeability is not only positively correlated with an increase in α-syn deposition in the intestine but also with an increase in the presence of intestinal bacteria and bacterial endotoxin (LPS).33

Studies have consistently shown altered fecal markers of inflammation (calprotectin) and intestinal permeability (zonulin and α-1-antitrypsin) in PD patients compared to healthy individuals, supporting the involvement of the gastrointestinal tract in PD development and progression.37 Furthermore, analyses of colon biopsies from 31 PD patients revealed alterations in the intestinal epithelial barrier proteins like occludin and zonula ocludens 1 (ZO-1), highlighting the potential role of these disruptions in PD pathology.20,38

Notably, shifts in specific bacterial genera important for intestinal barrier integrity, such as decreased Faecalibacterium, Roseburia, and Fusicatenibacter, and increased Akkermansia, have been observed in PD patients. Akkermansia, in particular, may contribute to intestinal epithelial permeability by degrading mucus, potentially exacerbating PD-related alterations.39

These findings lend support to Braak's hypothesis, proposing that intestinal epithelial barrier alterations facilitate the release of bacterial metabolites, proinflammatory cytokines, α-syn aggregates into the bloodstream, contributing to BBB disruption and PD pathology.40–42

The role of intestinal microbiota in Parkinson's diseaseThe intestinal microbiota comprises bacteria, viruses, and archaea residing in the digestive tract of many mammals including humans. It plays a pivotal role in the synthesis and release of neurotransmitters like DA and serotonin, in the metabolism of drugs such as L-DOPA, and the production of signaling molecules like SCFAs that regulate intestinal barrier integrity and immune function.43,44 Various factors including pathogens, drugs, and diet can alter the intestinal microbiota composition, leading to dysbiosis —a state associated with increased intestinal permeability, facilitating the release of neurotransmitters, pro-inflammatory cytokines and α-syn aggregates—. Dysbiosis, driven by α-syn overexpression, has been linked to motor symptoms and dopaminergic neurodegeneration.45–47

Accumulating evidence demonstrates dysbiosis and altered microbial metabolites in PD, with PD patients exhibiting excessive bacterial growth in the small intestine associated with symptoms like bloating, flatulence, malabsorption, and more severe motor deficits.48

Fecal samples from PD patients reveal decreased levels of anti-inflammatory bacteria (e.g. Lachnospiraceae, Roseburia and Faecalibacterium, Blautia, and Coprococcus) and increased pro-inflammatory bacteria, such as Akkermansia, shifting the microbial balance within the colon toward inflammation.49–52

Notably, decreased Prevotella genus in PD feces is associated with decreased mucin synthesis and increased intestinal permeability, potentially intensifying bacterial antigens translocation.53 Lower levels of Prevotella result in decreased levels of neuroactive SCFAs and increased capacity for thiamine and folate biosynthesis, which could explain the decreased vitamin levels observed in PD patients.33

Studies by Scheperjans et al. report a decrease in the abundance of 77.65% of bacteria from the Prevotellaceae family and an increase in the Enterobacteriaceae family in PD, with Enterobacteriaceae correlating with postural instability severity and walking difficulty.54 Additionally, several works have confirmed the decrease in the abundance of these same families of bacteria (Bacteroidetes, Prevotellaceae) in PD, accompanied by a decrease in the concentration of SCFA.55–57 Fiber is the primary substrate for the production of SCFA, including acetate, propionate, and butyrate, which are capable of altering intestinal barrier function and inhibiting intestinal inflammation.58

PD patients exhibit alterations in bacterial genera, with Escherichia, Shigella, Streptococcus, Proteus, and Enterococcus significantly increased in fecal samples. Streptococci, in particular, produce the neurotoxins streptomycin and streptokinase, causing neurological damage.59

Animal models of MPTP-induced PD show similar dysbiosis characterized by decreased Firmicutes and increased Proteobacteriaceae and Enterobacteriaceae in fecal samples, mirroring human PD dysbiosis.60 After three weeks, mice treated with rotenone also exhibited fecal microbial dysbiosis characterized by a general decrease in bacterial diversity and a significant change in the microbiota composition, with an increase in the Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes ratio.61

Similarly, rats treated with rotenone demonstrated delayed gastric emptying and pathological changes in the mucosa, such as thickening and hyperplasia of colonic goblet cells, associated with an imbalance of the intestinal microbiota, particularly, a decrease in beneficial species such as S24–7, Prevotella, and Oscillospira and an increase in potentially pathogenic species.62 Understanding the influence of the intestinal microbiota on CNS function and observing dysbiosis in both experimental and clinical models of PD suggest probiotics as a potential therapeutic avenue for PD treatment.63

Preclinical evidence: Probiotics in animal models of Parkinson's diseaseRodents are frequently used in Parkinson's disease research due to their neuroanatomical and behavioral similarities to humans.64 Various methods exist to induce a PD-like pathology in these animal models, primarily replicating the characteristic dopaminergic neuronal degeneration seen in the disease. One common approach is administering neurotoxins like 6-OHDA or MPTP, or pesticides such as rotenone or paraquat, all of which induce death of dopaminergic neurons. Another approach utilizes genetically modified mice that express mutations in PD-associated genes, such as alpha-synuclein, Parkin, or DJ-1. These genetic models are instrumental in investigating the roles these genes play in the pathogenesis of PD.65 Preserving intestinal homeostasis with probiotics offers a promising therapeutic strategy to improve health by enhancing digestion, nutrient absorption, immune function, and mitigating pro-inflammatory processes and neurodegeneration. This section summarizes the most important findings in preclinical studies that investigated the neuroprotective effects of various probiotics in PD.

In a murine model of MPTP-induced parkinsonism, the administration of a modified probiotic strain of Clostridium butyricum-GLP-1, which consistently expresses the peptide glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) —a key mediator in the regulation of the microbiota intestinal—, showed a decrease in motor dysfunction, an increase in the expression of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and a decrease in the expression of α-syn. Furthermore, C. butyricum-GLP-1 improved gut microbiota imbalance by decreasing the relative abundance of Bifidobacterium and promoted intestinal barrier integrity by regulating GPR41/43 levels. The neuroprotective effects of this strain appear to be mediated by the promotion of mitophagy —a process in which damaged mitochondria are eliminated to prevent oxidative stress and cell death— mediated by PINK1/Parkin.66,67 GLP-1 plays a critical role in the microbiota-gut-brain axis by inhibiting nuclear factor kappaB (NF-κB)-mediated neuroinflammation and microglial activation implicated in PD pathogenesis. Activation of the GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1R) in microglia inhibits inflammatory processes, suggesting it as a potential therapeutic target.68–70 The GLP-1R agonist Exendin-4 inhibited microgliosis and the release of the inflammatory mediators TNF-α and IL-1β in the SNpc and STR, and increased TH expression in a murine model of MPTP-induced parkinsonism.71 Chu et al. demonstrated that Lactobacillus plantarum CCFM405 administration improved motor dysfunctions induced by rotenone in the pole test, beam walking test, and rotarod test. This probiotic inhibited dopaminergic cell loss, reduced inflammatory markers in the SNpc and STR (GFAP, IBA-1, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α), and enhanced intestinal barrier integrity by inhibiting intestinal inflammation, increasing tight junction protein expression (ZO-1, occludin), and promoting microbial diversity.72 Although the mechanism by which L. plantarum CCFM405 exerts these effects has not been fully elucidated, this probiotic modulates the diversity of the gut microbiota by inducing an increase in the relative abundance of Bifidobacterium, Turicibacter, and Faecalibaculum, and a reduction in the relative abundance of Alistipes, Bilophila, Akkermansia, and Escherichia-Shigella.

However, it is important to mention that Bifidobacteria also possess significant neuroprotective effects. In fact, ingestion of B. breve CCFM1067 has been shown to restore the integrity of the BBB and intestinal barrier, alleviate intestinal dysbiosis, and increase the content of SCFAs (acetic acid, butyric acid, isobutyric acid, isovaleric acid) in an MPTP-induced Parkinsonism model.73

Furthermore, L. plantarum CCFM405 also increased the abundance of the genus Faecalibaculum, known to produce SCFAs.74 SCFAs were shown to have important neuroprotective effects by inhibiting oxidative stress through increased expression of the nuclear erythroid 2-related factor (NRF2), promoting gene expression of several antioxidant enzymes (Heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1 (NQO1), GPx, catalase, etc.) and decrease dopaminergic cell death in a 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA)-induced parkinsonism model.75 Therefore, one of the pathways through which L. plantarum CCFM405 exerts its neuroprotective effects is by increasing the abundance of certain SCFA-producing bacteria. Another mechanism by which probiotics may exhibit neuroprotective effects involves inhibiting the NLRP3 inflammasome at the microglial level. Although the pathogenesis of PD is not yet fully understood, neuroinflammation is recognized as a significant factor. Microglial cells, the resident immune cells of the brain, support neurogenesis and synaptic pruning under normal conditions by clearing cellular debris to maintain brain development and homeostasis. However, in the presence of neuronal damage, cytotoxic events, or exposure to toxins such as MPTP or 6-OHDA, these cells can shift from a neuroprotective (M0) to a pro-inflammatory (M1) state. This transition leads to the release of inflammatory mediators including IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-18, and NLRP3 (NOD-, LRR-, and pyrin domain-containing protein 3), exacerbating damage to dopaminergic neurons.76 Thus, targeting microglial activation could be a promising therapeutic strategy to mitigate the degeneration and death of dopaminergic neurons. Fan et al. demonstrated that heat-inactivated Lactobacillus murinus strains confer neuroprotection against the loss of dopaminergic neurons by inhibiting the NLRP3 inflammasome, increasing TH expression in the SNpc, and improving performance in motor tests in a 6-OHDA-induced Parkinsonism model.77 The probiotic formulation Symprove, comprising four bacterial strains: Lactobacillus acidophilus NCIMB 30175, Lactobacillus plantarum NCIMB 30173, Lactobacillus rhamnosus NCIMB 30174, and Enterococcus faecium NCIMB 30176, has shown effectiveness in improving symptoms of diverticular disease and ulcerative colitis due to its resistance to gastric acidity.28,78 These properties also suggest potential benefits for treating Parkinsonism, by inhibiting dopaminergic cell death and enhancing intestinal function. Experimental studies have shown that this probiotic mixture reduces intestinal tissue damage by increasing the expression of the tight junction protein occludin and reducing levels of inflammatory mediators such as IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in both intestinal and plasma samples.79,80 Additionally, changes in intestinal microbiota composition, including Acetatifactor, Alloprevotella, Lachnospiraceae_NC2004, Ruminococcus_torques, and UCG_009, were noted. Furthermore, alterations of glial cell morphology and activation in the STR, as well as increased TH expression in the SNpc, were observed.80,81 Although these studies do not fully elucidate the mechanism of actions, the findings suggest that a combination of multiple probiotics may act synergistically to enhance neuroprotective effects in the SNpc, potentially slowing the progression of dopaminergic neuron degeneration. Below, we summarize the key experimental evidence demonstrating the neuroprotective effects of probiotics in various animal models of Parkinsonism (Table 1).

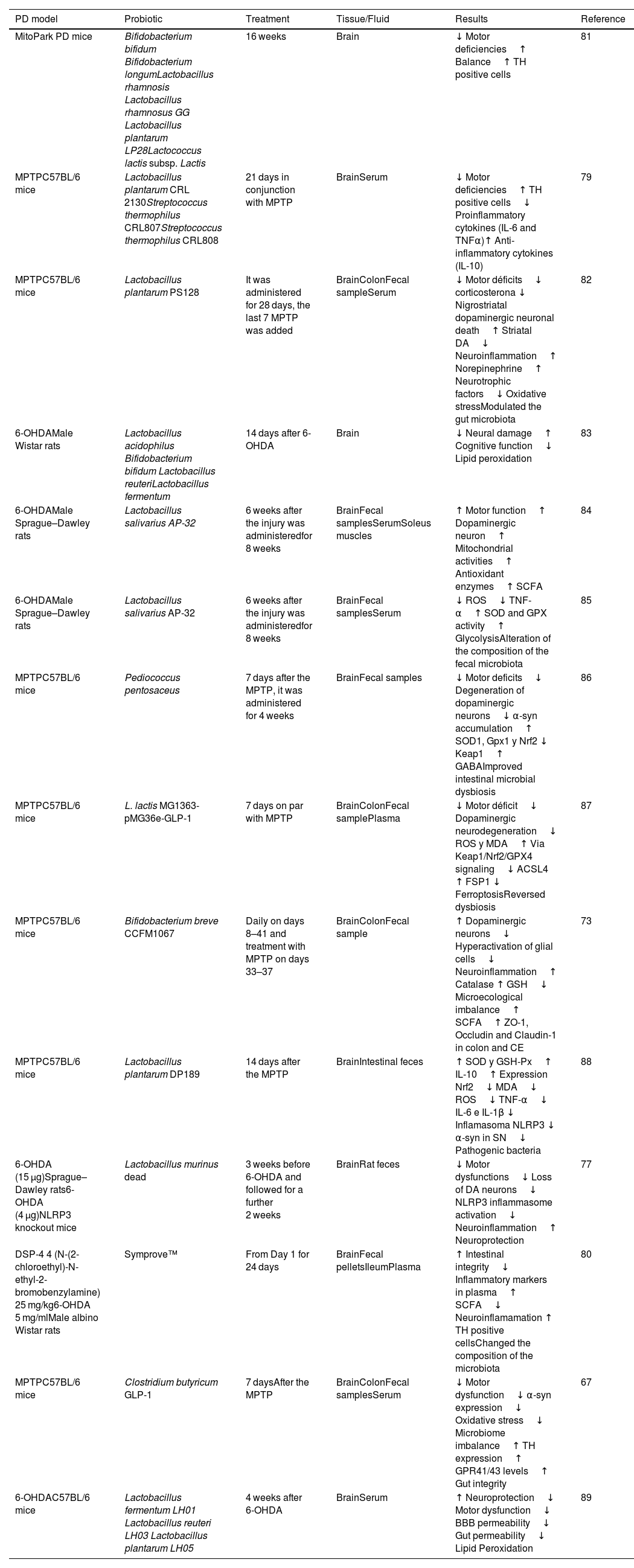

Preclinical studies in animal models: Effect of probiotic administration on Parkinson's disease.

| PD model | Probiotic | Treatment | Tissue/Fluid | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MitoPark PD mice | Bifidobacterium bifidum Bifidobacterium longumLactobacillus rhamnosis Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG Lactobacillus plantarum LP28Lactococcus lactis subsp. Lactis | 16 weeks | Brain | ↓ Motor deficiencies↑ Balance↑ TH positive cells | 81 |

| MPTPC57BL/6 mice | Lactobacillus plantarum CRL 2130Streptococcus thermophilus CRL807Streptococcus thermophilus CRL808 | 21 days in conjunction with MPTP | BrainSerum | ↓ Motor deficiencies↑ TH positive cells↓ Proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6 and TNFα)↑ Anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10) | 79 |

| MPTPC57BL/6 mice | Lactobacillus plantarum PS128 | It was administered for 28 days, the last 7 MPTP was added | BrainColonFecal sampleSerum | ↓ Motor déficits↓ corticosterona ↓ Nigrostriatal dopaminergic neuronal death↑ Striatal DA↓ Neuroinflammation↑ Norepinephrine↑ Neurotrophic factors↓ Oxidative stressModulated the gut microbiota | 82 |

| 6-OHDAMale Wistar rats | Lactobacillus acidophilus Bifidobacterium bifidum Lactobacillus reuteriLactobacillus fermentum | 14 days after 6-OHDA | Brain | ↓ Neural damage↑ Cognitive function↓ Lipid peroxidation | 83 |

| 6-OHDAMale Sprague–Dawley rats | Lactobacillus salivarius AP-32 | 6 weeks after the injury was administeredfor 8 weeks | BrainFecal samplesSerumSoleus muscles | ↑ Motor function↑ Dopaminergic neuron↑ Mitochondrial activities↑ Antioxidant enzymes↑ SCFA | 84 |

| 6-OHDAMale Sprague–Dawley rats | Lactobacillus salivarius AP-32 | 6 weeks after the injury was administeredfor 8 weeks | BrainFecal samplesSerum | ↓ ROS↓ TNF-α↑ SOD and GPX activity↑ GlycolysisAlteration of the composition of the fecal microbiota | 85 |

| MPTPC57BL/6 mice | Pediococcus pentosaceus | 7 days after the MPTP, it was administered for 4 weeks | BrainFecal samples | ↓ Motor deficits↓ Degeneration of dopaminergic neurons↓ α-syn accumulation↑ SOD1, Gpx1 y Nrf2 ↓ Keap1↑ GABAImproved intestinal microbial dysbiosis | 86 |

| MPTPC57BL/6 mice | L. lactis MG1363-pMG36e-GLP-1 | 7 days on par with MPTP | BrainColonFecal samplePlasma | ↓ Motor déficit↓ Dopaminergic neurodegeneration↓ ROS y MDA↑ Via Keap1/Nrf2/GPX4 signaling↓ ACSL4 ↑ FSP1 ↓ FerroptosisReversed dysbiosis | 87 |

| MPTPC57BL/6 mice | Bifidobacterium breve CCFM1067 | Daily on days 8–41 and treatment with MPTP on days 33–37 | BrainColonFecal sample | ↑ Dopaminergic neurons↓ Hyperactivation of glial cells↓ Neuroinflammation↑ Catalase ↑ GSH↓ Microecological imbalance↑ SCFA↑ ZO-1, Occludin and Claudin-1 in colon and CE | 73 |

| MPTPC57BL/6 mice | Lactobacillus plantarum DP189 | 14 days after the MPTP | BrainIntestinal feces | ↑ SOD y GSH-Px↑ IL-10↑ Expression Nrf2↓ MDA↓ ROS↓ TNF-α↓ IL-6 e IL-1β ↓ Inflamasoma NLRP3 ↓ α-syn in SN↓ Pathogenic bacteria | 88 |

| 6-OHDA (15 μg)Sprague–Dawley rats6-OHDA (4 μg)NLRP3 knockout mice | Lactobacillus murinus dead | 3 weeks before 6-OHDA and followed for a further 2 weeks | BrainRat feces | ↓ Motor dysfunctions↓ Loss of DA neurons↓ NLRP3 inflammasome activation↓ Neuroinflammation↑ Neuroprotection | 77 |

| DSP-4 4 (N-(2-chloroethyl)-N-ethyl-2-bromobenzylamine) 25 mg/kg6-OHDA 5 mg/mlMale albino Wistar rats | Symprove™ | From Day 1 for 24 days | BrainFecal pelletsIleumPlasma | ↑ Intestinal integrity↓ Inflammatory markers in plasma↑ SCFA↓ Neuroinflamamation ↑ TH positive cellsChanged the composition of the microbiota | 80 |

| MPTPC57BL/6 mice | Clostridium butyricum GLP-1 | 7 daysAfter the MPTP | BrainColonFecal samplesSerum | ↓ Motor dysfunction↓ α-syn expression↓ Oxidative stress↓ Microbiome imbalance↑ TH expression↑ GPR41/43 levels↑ Gut integrity | 67 |

| 6-OHDAC57BL/6 mice | Lactobacillus fermentum LH01 Lactobacillus reuteri LH03 Lactobacillus plantarum LH05 | 4 weeks after 6-OHDA | BrainSerum | ↑ Neuroprotection↓ Motor dysfunction↓ BBB permeability↓ Gut permeability↓ Lipid Peroxidation | 89 |

Experimental studies in animal models have elucidated the role of the intestinal microbiota and probiotics in PD, highlighting their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. This section reviews clinical evidence supporting the effectiveness of probiotic supplementation in PD patients.

A double-blind, randomized, controlled study involving PD patients revealed that supplementation with a probiotic blend containing Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium bifidum, Lactobacillus reuteri and Lactobacillus fermentum for 12 weeks reduced mRNA expression levels of the inflammatory markers:IL-8, IL-1β, and TNF-α. This supplementation also increased transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) expressions.90 Subsequently, the same research team demonstrated that this probiotic supplementation improved Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) scores, reduced C-reactive protein (CRP), malondialdehyde (MDA) and increased glutathione levels.91 Elevated inflammatory markers are linked to heightened microglial activation, which can exacerbate neurodegeneration through the release of free radicals and proinflammatory cytokines. Changes in inflammatory processes are closely associated with nervous system alterations, primarily due to alterations in the permeability of the intestinal barrier and the BBB. Therefore, controlling inflammatory marker levels may help alleviate inflammation and restore nervous system functions. The intake of probiotics (Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium bifidum, Lactobacillus reuteri, and Lactobacillus fermentum) may reduce inflammation, both peripherally and at the CNS level, by inhibiting the NF-kB and MAPK pathways.

In addition to the characteristic motor symptoms of PD, resulting from the progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons in the SNpc and the aggregation of α-syn into Lewy bodies,92 non-motor symptoms significantly impact the quality of life in PD patients, affecting up to 90% of individuals.93 These symptoms, including depression, anxiety, and cognitive disorders, are associated with disease progression, often appearing before motor symptoms.94–96

Clinical evidence has demonstrated that neuropsychiatric complications in PD patients, including anxiety and depression, are associated to DA, serotonin, and noradrenaline dysregulation.97,98 Dysbiosis of the intestinal microbiota, along with genetic and environmental factors, inflammation, and oxidative stress, contributes to the onset of neuropsychiatric disorders.99,100 Oxidative stress, characterized by increased levels of free radicals and a decrease in antioxidant capacity,101 is crucial in promoting neurodegeneration of dopaminergic cells in the SNpc.102 Supplementation with symbiotics —the combination of probiotics and prebiotics— containing the beneficial probiotics Lactobacillus acidophilus (LAA-5), Lactobacillus rhamnosus (LAR-7), Lactobacillus plantarum (LAP-10), Bifidobacterium longum (BIA-8), and Streptococcus thermophilus for 12 weeks increased glutathione (GHS) antioxidant capacity and reduced MDA levels in PD patients. This intervention also decreased depressive symptoms and improved cognitive process.103 Symbiotics may modulate intestinal and brain functions by modifying inflammatory and oxidative responses.104

Constipation, a prodromal symptom of PD, affects up to 90% of patients.105 Dysfunction of the enteric nervous system (ENS) leads to gastrointestinal motility impairment due to α-syn aggregation. Moreover, most PD patients take antiparkinsonian medications, which can also influence gastrointestinal motility through their side effects.106

Treatment with Hexbio, a combination of probiotics (Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus casei, Lactobacillus lactis, Bifidobacterium infantis, and Bifidobacterium longum), along with the prebiotic fiber fructooligosaccharide, effectively inhibited inflammation and abdominal pain, while improving stool consistency and frequency.107 These beneficial effects are attributed to its ability to modulate the composition of the intestinal microbiota and SCFAs levels, which are altered in PD patients and experimental animals with Parkinsonism,24,57,108 thereby promoting intestinal barrier integrity, mucosal repair, improved intestinal motility, and modulation of pro-inflammatory responses109 (Table 2).

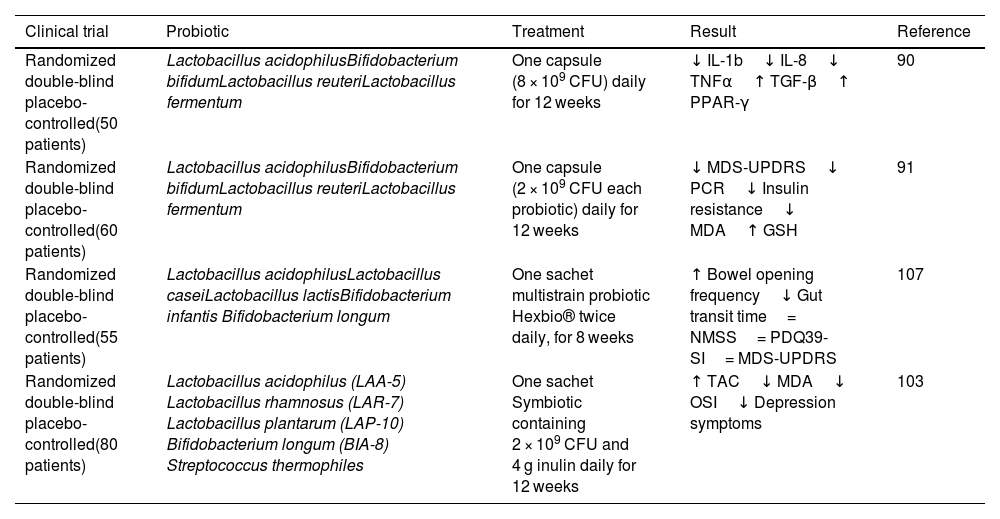

Summary of clinical studies in patients with Parkinson's disease after administration of probiotics versus placebo (Abbreviations: NMSS, No Motor Symptom Scale; PDQ39-SI, Parkinson's Disease Questionare 39 summary indices for quality of life).

| Clinical trial | Probiotic | Treatment | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled(50 patients) | Lactobacillus acidophilusBifidobacterium bifidumLactobacillus reuteriLactobacillus fermentum | One capsule (8 × 109 CFU) daily for 12 weeks | ↓ IL-1b↓ IL-8↓ TNFα↑ TGF-β↑ PPAR-γ | 90 |

| Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled(60 patients) | Lactobacillus acidophilusBifidobacterium bifidumLactobacillus reuteriLactobacillus fermentum | One capsule (2 × 109 CFU each probiotic) daily for 12 weeks | ↓ MDS-UPDRS↓ PCR↓ Insulin resistance↓ MDA↑ GSH | 91 |

| Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled(55 patients) | Lactobacillus acidophilusLactobacillus caseiLactobacillus lactisBifidobacterium infantis Bifidobacterium longum | One sachet multistrain probiotic Hexbio® twice daily, for 8 weeks | ↑ Bowel opening frequency↓ Gut transit time= NMSS= PDQ39-SI= MDS-UPDRS | 107 |

| Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled(80 patients) | Lactobacillus acidophilus (LAA-5) Lactobacillus rhamnosus (LAR-7) Lactobacillus plantarum (LAP-10) Bifidobacterium longum (BIA-8) Streptococcus thermophiles | One sachet Symbiotic containing 2 × 109 CFU and 4 g inulin daily for 12 weeks | ↑ TAC↓ MDA↓ OSI↓ Depression symptoms | 103 |

Probiotics have shown promising results in regulating prodromal and motor symptoms, as well as modulating inflammatory responses, oxidative stress, and changes in intestinal microbiota. While the precise mechanism of probiotic action remains unclear, evidence suggests several potential pathways through which probiotics exert neuroprotective effects within the ENS and CNS.

Protofibrils of α-syn exert toxic effects on gastrointestinal function, increasing intestinal barrier permeability.110 Preclinical and clinical studies have associated increased intestinal barrier permeability with elevated systemic LPS levels and α-syn deposits in the colon.35 Intestinal dysbiosis, characterized by an increase in pathogenic bacteria and a reduction in beneficial bacteria producing SFCAs, exacerbates intestinal barrier damage and inflammation, promoting leaky gut syndrome,57,111 further exposing the intestinal neural plexus to toxins like LPS, promoting abnormal α-syn aggregation and Lewy bodies formation.

Decreased expression of tight junction proteins, such as ZO-1 and occludin, triggers intestinal inflammation and barrier dysfunction through inflammasome activation (NLRP3, IL-1β, caspase-1). PD patients exhibit elevated inflammatory markers (calprotectin and lactoferrin) and reduced SCFA concentrations (acetic, butyric, and propionic acids) in stools.112

SCFAs, besides enhancing intestinal barrier stability, provide energy to epithelial cells and regulate tight junction protein expression by stabilizing Hypoxia Inducible Factor and AMP-activated kinase.58,113 Propionate administration increases tight junction protein expression (ZO-1 and occludin) via AKT signaling, reducing intestinal permeability.114

Sodium butyrate improved motor symptoms and neurodegeneration in a Parkinsonism model. It attenuated the expression of microglial cell and inflammatory markers IL-6 and TNF-α, while also inhibiting intestinal permeability by increasing the expression of tight junction proteins such as Occludin and Claudin.115 Although the exact underlying mechanism of these effects is still unclear, sodium butyrate has been shown to inhibit intestinal inflammation by activating the GPR109A receptor, which induces the secretion of the cytokine IL-18 in the colonic epithelium and promotes the differentiation of Treg cells and IL-10-producing T cells.116 Furthermore, sodium butyrate appears to inhibit the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB pathway in the colon, where the Toll-like receptor TLR4 plays a critical role in the genesis of PD by modulating intestinal inflammatory responses. TLR4 recognizes LPS produced by Proteobacteria and activates the MyD88-dependent NF-κB signaling pathway, leading to the release of TNF-α and IL-6, which perpetuates inflammation.117 Epidemiological studies have shown elevated levels of TLR4 protein in colon biopsies and circulating monocytes of PD patients. In murine models of rotenone-induced Parkinsonism, TLR4 knockout mice exhibited preserved integrity of the intestinal barrier compared to wild-type animals.20

Oxidative stress plays a key role in PD pathophysiology, with increased oxidized biomolecules (lipids, proteins, and DNA) and reduced GSH levels observed oxidative stress increases not only during DA metabolism and neuroinflammation118 but also with aging due to decreased antioxidant capacity, increased mitochondrial dysfunction, and alterations in metal homeostasis.119 Moreover, oxidative stress activates enteric neurons and glial cells, contributing to α-syn aggregation in the ENS.120 This accumulation of α-syn in the gut can migrate to the brain, leading to increased microglial activation and promoting further oxidative stress, which exacerbates neuroinflammation.121 Therefore, therapies focused on mitigating oxidative stress could potentially slow the progression of PD. Several studies have indicated that maintaining a healthy gut microbiota can exert significant antioxidative and anti-inflammatory effects.

Probiotic supplementation with Lactobasullus salivarius AP-32 for 8 weeks increases the antioxidant capacity of SOD, GPx, and catalase, and SCFA concentrations (propionic and butyric acid), while preventing neurodegeneration in a 6-OHDA-induced Parkinsonism model.85 SCFA may activate NRF2 to inhibit oxidative stress by impeding histone deacetylase (HDAC) activity and promoting antioxidant gene expression. SCFAs enter cells through transporters like MCT1 and FAT/CD36, or by activating receptors such as GPR41.122 Inside the cell, SCFAs inhibit HDAC activity, enhancing histone acetylation which promotes the expression of the Nrf2 gene.123 NRF2 then translocates to the nucleus to bind with its antioxidant response element (ARE), enhancing the expression of several antioxidant enzymes (HO-1, NQ01, GPx, catalase, etc.) and reducing oxidative stress driven by ROS. By enhancing intestinal barrier integrity, probiotics reduce systemic inflammation associated with bacterial products and α-syn deposition, making SCFAs a therapeutic target to restore intestinal epithelial function and alleviate neuroinflammation in PD models and patients.

Challenges and future directions: Expanding our understanding and optimizing probiotic interventionsPD is a complex neurodegenerative disorder with diverse underlying mechanisms, making it challenging to establish precise relationships between gut microbiota, inflammation, and disease progression. Variability in symptom manifestation, progression, and contributing factors further complicates the identification of consistent patterns or universally applicable interventions.

Further research is imperative to deepen our comprehension of the interplay between gut microbiota composition, inflammation, and neurodegeneration in PD. However, collectively, the most recent findings highlight the neuroprotective potential of probiotics in PD models. Further clinical trials are necessary to confirm their efficacy and safety for human PD patients. It is also crucial to explore the mechanisms through which gut microbiota influences the CNS, including pathways like the gut-brain axis, immune system interactions, and the potential role of neuroactive compounds produced by gut microbiota.

Protection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

FundingThis study was supported by Consejo Nacional de Humanidades Ciencia y Tecnología (CONAHCYT) project (#281452) granted to Dr. M. E. Flores-Soto and Scholarship (CONAHCYT #1099710) granted to Angelica Yanet Nápoles Medina.

The authors declare no financial or competing interests.