Neurological disorders present a significant global health challenge, with limited effective treatment options due to the complex and selective nature of the blood–brain barrier (BBB). Recent years have witnessed remarkable advancements in nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems designed to overcome these barriers and enhance the therapeutic outcomes of neurological disorder treatments. Among these innovations, nasal drug delivery has emerged as a promising non-invasive approach to bypass the BBB and directly target the central nervous system (CNS). This article provides an overview of the origin of nanotechnology and its intersection with biotechnology, leading to the emergence of nanobiotechnology. It highlights the role of nanotechnology in drug delivery and its potential to enhance the effectiveness of nanoscale structures in biomedical science. The article emphasizes the significance of the chemical composition of nanoparticles (NPs) in determining their physiochemical properties and drug-release behavior. The challenges posed by the BBB in delivering drugs to the CNS and the limited permeability of macromolecules to the barrier. The article emphasizes the role of the BBB as a diffusion barrier and explains the mechanisms by which molecules can cross the barrier. It mentions the presence of interendothelial junctions and receptors/transporters in endothelial cells that regulate the permeability of the BBB. Overall, the article provides an overview of the role of nanoparticles in drug delivery through the nasal route for the treatment of neurological disorders.

Los trastornos neurológicos presentan un importante desafío para la salud mundial, con opciones de tratamiento efectivas limitadas debido a la naturaleza compleja y selectiva de la barrera hematoencefálica (BHE). Los últimos años han sido testigos de avances notables en los sistemas de administración de fármacos basados en nanopartículas diseñados para superar estas barreras y mejorar los resultados terapéuticos de los tratamientos de trastornos neurológicos. Entre estas innovaciones, la administración nasal de fármacos ha surgido como un enfoque no invasivo prometedor para evitar la BHE y apuntar directamente al sistema nervioso central (SNC). Este artículo proporciona una visión general del origen de la nanotecnología y su intersección con la biotecnología, lo que llevó al surgimiento de la nanobiotecnología. Destaca el papel de la nanotecnología en la administración de fármacos y su potencial para mejorar la eficacia de las estructuras a nanoescala en la ciencia biomédica. El artículo enfatiza la importancia de la composición química de las nanopartículas (NP) para determinar sus propiedades fisicoquímicas y su comportamiento de liberación de fármacos. Los desafíos que plantea la BHE en la entrega de fármacos al SNC y la permeabilidad limitada de las macromoléculas a la barrera. El artículo enfatiza el papel de la BBB como barrera de difusión y explica los mecanismos por los cuales las moléculas pueden cruzar la barrera. Menciona la presencia de uniones interendoteliales y receptores/transportadores en las células endoteliales que regulan la permeabilidad de la BHE. En general, el artículo proporciona una visión general del papel de las nanopartículas en la administración de fármacos por vía nasal para el tratamiento de trastornos neurológicos.

The origin of nanotechnology from 1959 when physicist Richard Feynman has been identified the potential of manipulating individual atoms and molecules at the nanometer scale and planned that material at this scale possesses novel physical properties.1 Nanobiotechnology emerged as the intersection between nanotechnology and biotechnology, playing a critical role in drug delivery and enhancing the effectiveness of nanoscale structures in biomedical science.2 This convergence has paved the way for the development of numerous innovative carriers capable of facilitating controlled release and targeted delivery of a wide array of therapeutic molecules, including proteins, peptides, genes, interleukins, growth factors, and various chemical drugs.3 The chemical composition of nanoparticles (NPs) can significantly influence their physiochemical properties, including sizes, shapes, and drug-release behavior.4 In recent decades, there has been a notable increase in the synthesis of novel metal nanoparticles such as silver, gold, platinum, and palladium, driven by the growing demand for environmentally friendly material synthesis technologies.5 NPs have attracted considerable attention due to their small size and large surface-to-volume ratio, which endow them with unique characteristics when compared to larger particles in bulk materials.6 Nanotechnology offers exciting new approaches for disease targeting and diagnostics.7 The advantages of these nanomaterials, including their structures, sizes, shapes, and surfaces, make them easily functionalize for targeted applications. NP-based targeting strategies have shown promising results in disease targeting.8 The shape, size, and surface properties of NPs play a crucial role in achieving effective drug delivery.9 The primary objective of nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems is to improve drug release kinetics while minimizing side effects, avoiding nanocarrier degradation in the physiological environment, and minimizing off-target effects. NPs have demonstrated the potential to enhance pharmacokinetics and cellular uptake.10 This review focuses on using nanoparticles for drug delivery via the nasal route in treating neurological disorders.11 It thoroughly examines the role of nanoparticles, exploring their nano formulation and delivery aspects while emphasizing their application through the nasal route.12

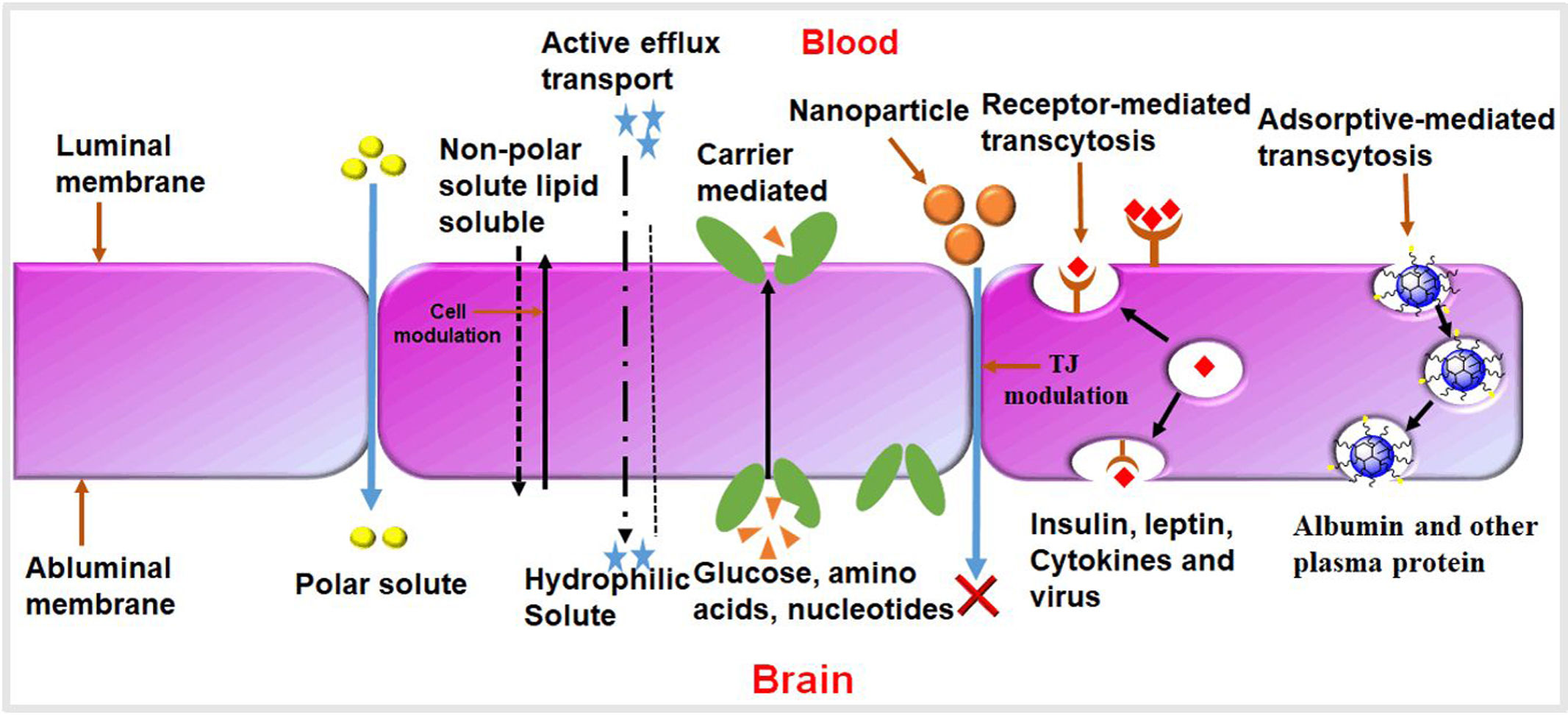

Overview of neurological disorders and their impactMost researchers have been exploring the nasal route as an alternative means to enhance drug targeting for the treatment of CNS disorders.13 Compared to conventional routes like parenteral (injection) or oral administration, the nose-to-brain route has emerged as a promising option.14 This approach allows drugs to be delivered directly from the nose to the brain, bypassing the need to traverse the BBB.15 The BBB is a complex barrier composed of tightly connected endothelial capillary cells, pericytes, astroglia, and perivascular mast cells.16 Its main function is to protect the brain by preventing t he entry of pathogens and unwanted particles, effectively blocking about 98% of molecules from the bloodstream.13 Only lipophilic and low molecular weight molecules, such as glucose and ions, can easily cross the BBB endothelial cells.17 The CNS also possesses other barriers, including the blood–cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) barrier, the blood–spinal cord barrier, and the blood–retinal barrier.18

Need for effective drug delivery systems for neurological disordersThe incidence rate of brain-related diseases, particularly neurodegenerative disorders like Parkinson's and Alzheimer's, has increased between 1990 and 2017 due to population aging.19 The fatality rate remains high, with two-thirds of cancer patients failing to survive within five years of diagnosis.12 The significant challenges in diagnosing and treating brain-related diseases are primarily attributed to the blood–brain barrier (BBB), which acts as a vital diffusion barrier, restricting the infiltration of macromolecules except for lipid-soluble compounds with small molecular weights20 (Fig. 1). These junctions facilitate the paracellular pathway, enabling the passage of small water-soluble substances through the BBB via diffusion.21 For high-molecular weight species like proteins and peptides, delivery into the brain is regulated by receptors and transporters present in endothelial cells, utilizing the transcellular pathway.22

Significance of the nasal route for drug delivery to the brainSeveral strategies have been identified for drug delivery to the brain.11 Firstly, drugs can be delivered locally through direct injection using a convection-enhanced delivery system. Biodegradable polymer implants can also be utilized for sustained drug release, although this method requires surgery and is highly invasive, typically reserved for treating brain diseases.12 Another alternative for bypassing the BBB is the intranasal route, where drugs loaded into nan carriers can be transported through the olfactory bulb (olfactory pathway) and the trigeminal nerve (trigeminal pathway) directly to the CNS.23 This innovative approach has gained considerable attention in recent years and shows promise. However, the intranasal route has limitations, such as variable drug delivery depending on the condition of the nasal mucosa. One of the traditional methods to enhance drug penetration across the BBB is to modify the molecular structure of the drugs or use prodrugs.24 Nanoparticles offer several advantages over conventional drug delivery approaches, primarily due to their ability to directly cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and target the central nervous system (CNS). The nasal route provides an additional advantage by bypassing the BBB through direct nose-to-brain pathways, utilizing the olfactory and trigeminal nerves for rapid CNS access. Nanotechnology and nasal administration combination enables more efficient drug delivery with potentially enhanced therapeutic outcomes.

Types of nanoparticles for drug deliveryNanoparticles are biocompatible, they are increasingly being explored as nano-therapeutics for disease treatment, with the potential to overcome drug resistance and achieve higher intracellular drug accumulation.25 The advancements in cancer nanotechnology in recent times present promising prospects for targeted drug delivery.26

Polymeric nanoparticlesPolymeric nanoparticles (PNPs) have significant interest in recent years due to their unique properties and behaviours resulting from their small size, as highlighted by various authors.27 These nanoparticulate materials exhibit potential for a wide range of applications, including diagnostics and drug delivery.25 The advantages of PNP nanoparticles include controlled release behavior, their potential for use in therapy and imaging, protection of drug molecules, and site-specific targeting to improve the therapeutic index (TI).24 The common mechanism for controlling drug release behavior from PNPs involves tuning the rates of polymer biodegradation and drug diffusion out of the polymer matrix. Currently, there is particular interest in exogenous and endogenous stimuli-responsive drug release, as it allows selectivity within the microenvironment of specific diseases.28 Nanoparticles have the potential to enhance existing disease therapies by overcoming multiple biological barriers and delivering a therapeutic load within the optimal dosage range.29 Polymer materials offer the best combination of stability and high loading capacity for various agents.26 They enable controlled drug release behavior, can be easily modified to display different surface-attached ligands, and many polymers have a long history of safe use in humans.25 Current strategies to overcome this challenge include temporary disruption of the blood–brain barrier (BBB), conjugation of brain-permeable ligands to the desired drug, intranasal delivery, or direct delivery of molecules into the brain through invasive techniques.30 Among these strategies, nanocarriers decorated with brain-targeting ligands are emerging as a non-invasive approach.22 Polymeric nanoparticles (NPs) composed of the FDA-approved polymer poly (d,l lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) and surface-engineered with the g7 glycopeptide (Gly-l-Phe-d-Thr-Gly-l-Phe-l-Leu-l-Ser(O-beta-d-glucose)-CONH2) have been reported to transport molecules into the central nervous system (CNS) following systemic administration in rodents.31

Lipid-based nanoparticlesLipid-based nanoparticle (LBNP) systems are considered one of the most promising colloidal carriers for bioactive organic molecules.32 LBNPs offer several advantages, including high temporal and thermal stability, a high loading capacity, ease of preparation, low production costs, and the ability for large-scale industrial production using natural sources.33 LBNPs have been extensively studied in both in vitro and in vivo cancer therapy, showing promising results in certain clinical trials.34,35 This review provides a summary of recent developments in LBNPs and their application in cancer treatment, including essential assays conducted in patients.30,31 LBNPs have gained significant attention as nanoscale delivery systems to enhance the oral bioavailability of poorly absorbed bioactive compounds for health promotion and disease prevention.29 However, they are absorbed through the intestinal lumen into the circulation remains unclear.36 This paper aims to provide an overview of the biological fate of orally administered LBNPs by reviewing recent studies conducted on cell and animal models.37 In general, the biological fate of ingested LBNPs in the gastrointestinal tract is primarily determined by their initial physicochemical characteristics, such as particle size, surface properties, composition, and structure.38 LBNPs can be either digestible or indigestible, resulting in two distinct biological fates for each type of LBNP.39 The review discusses the detailed absorption mechanisms and uptake pathways at the molecular, cellular, and whole-body levels for each type of LBNP. Additionally, it addresses the limitations of current research and provides insights into future directions for studying the biological fate of ingested LBNPs.31,39

Inorganic nanoparticlesThe field of nanotechnology offers significant potential for cancer imaging and therapy, with innovative nanoplatforms being developed for biomedical applications.40 In the process of translating these platforms to clinical use, inorganic nanoplatforms encounter greater challenges compared to organic systems.41,42 The development of applications in this field is progressing rapidly, and various inorganic platforms have demonstrated potential in both preclinical and clinical trials.43 In comparison to quantum dots (QDs) that contain heavy metals, iron-based nanoparticles are considered less toxic, as the degradation byproduct of IONPs, iron ions, are essential as trace elements and the mechanisms of iron transport and regulation are well understood.44

Hybrid nanoparticlesPolymer–lipid hybrid systems (PLHNPs) emerged to overcome the shortcomings of polymeric and lipid-based formulations such as the slow degradation rate, lack of loading capacity, stability, and leaking capacity. The polymer controls the release, and lipids enhance the loading efficiency as well as permeation.31 Additionally, PLHNPs exhibit complementary characteristics to polymeric nanoparticles by comprising polymeric cores and lipid/lipid–PEG shells, which create core–shell nanoparticles with high structural integrity43 (Table 1). The aim of this studies to explore the production of hybrid nanoparticles composed by CHL and PLGA modified with g7 ligand has been cross BBB (Fig. 2). The effect of ratio between components (Chol and PLGA) and formulation process (nanoprecipitation or single emulsion process) on physico-chemical and structural characteristics, we tested MIX-NPs in vitro using primary hippocampal cell cultures evaluating possible toxicity, uptake, and the ability to influence excitatory synaptic receptors.44 The formulation approach impacted the construction and reorganization of components leading to some differences in CHL availability between the two types of g7 MIX-NPs. Our data hint that formulations of MIX-NPiscapably taken up by neurons, able to escape lysosomes and release CHL into the cells resulting in an efficient modification in expression of synaptic receptors that could be beneficial in HD.45

Targeting ligand for brain drug delivery.

| Ligand | Drug | Disease | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Azido-PEG-4-amine and azido-PEG-6-acid | Sinomenine | Traumatic brain injury | 46 |

| Sialic acid (S), glucosamine (G) and concanavalin | Paclitaxel | Treatment of cancer | 47 |

| N-acetyl-d-glucosamine-labelled | Camptothecin | Cancer drug delivery | 48 |

| Polyethylene glycol (PEG) and folic acid (FA) | 5-Fluorouracil | Diagnosis, and treatment | 40 |

| Poly (ethylene glycol) (PEG) | PEG-SOD (PEGylated Superoxide Dismutase) | Brain ischemia disease | 39 |

| N-acetyl-l-cysteine (NAC) | N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) it self | Treatment of neurological disorders | 38 |

| Albumin | Doxorubicin | Glioblastoma | 32 |

| Transferrin | plasmid DNA | Gene delivery to brain | 33 |

| Lactoferrin | Paeoniflorin | Brain targeting | 25 |

| Hyaluronic acid | temozolomide | Brain tumor | 50 |

| Borneol (BO) and polyethylene glycol (PEG) | Itraconazole | Brain targeted | 43 |

| Polysorbate 80 | Carboplatin | Malignant brain tumor | 39 |

These pathways allow nanoparticles to bypass systemic circulation and directly access the brain. The discussion explains how particle size, surface charge, and surface modifications, such as PEGylation, can influence nanoparticles’ ability to penetrate these pathways.22

Factors influencing absorption efficiencyParameters such as the residence time of nanoparticles in the nasal cavity, mucociliary clearance, and the presence of absorption enhancers are critical determinants of drug delivery efficiency. Mucoadhesive nanoparticles or those incorporating permeation enhancers may improve retention and absorption.32

Impact of nanoparticle surface functionalizationSurface modifications can be used to target specific receptors on the nasal mucosa or brain cells, enhancing cellular uptake and drug delivery to the CNS. Ligand-conjugated nanoparticles, for example, can improve targeted delivery to neuronal receptors.33

Therapeutic applicationsTheragnostic nanoparticles for diagnosis and treatmentNanoparticles (NPs) have garnered significant attention as a promising tool for both diagnosis and therapeutics.12 A wide range of nanoparticles has been designed with adjustable functional surfaces and bioactive cores, enabling them to exhibit numerous advantageous therapeutic and diagnostic properties. In age-related neurodegenerative disorders like Parkinson's disease (PD), a progressive loss of dopamine-producing cells is a hallmark feature. However, dopamine cannot naturally cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB) (Table 2). To overcome this limitation, novel approaches involving DA-nanoencapsulation therapies are actively being pursued to enable the delivery of dopamine to the brain.34

Lactoferrin as a targeting ligand for brain drug delivery.

| Ligand | Drug | Targeted organ | Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LF-MDCs | DOX/CUR | Brain | Enhanced antitumor effect in BALB/c female nude micebearingRG2 cells. | 51 |

| LF-MIONs | PFH-PTX | Brain | Improved in vivo antitumor effect in solid brain tumor. | 54 |

| LF-PDNCs | CUR | Brain | Improved in vivo anti-tumor efficiency in brain tumor bearing rats. | 52 |

| LF-GO@Fe3O4 | DOX | Brain | Increased anticancer activity Against C6 glioma cells. | 47 |

| LF-PAMAM-PGG | DNA | Brain | Higher in vivo brain accumulation and transfection activity | 36 |

| LF-PAMAM-PEG | hGDNF | Brain | Enhanced in vivo neuroprotective effect in PD rat model. | 35 |

| LF-PAMAM | RIV | Brain | Enhanced learning ability in AD animal model. | 21 |

| LF-PEG–PLA | UCN | Brain | Attenuated striatum lesions in AD bearing rats. | 29 |

| LF-PEG–PLA | PTX | Brain | Enhanced anti-glioma effect in nude mice. | 32 |

| LF-PEG-PLGA | Rotigotine | Brain | Decreased nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurodegeneration in PD animal model. | 33 |

| LF-B-mPEG-PLGA | Dopamine | Brain | Improved dopamine accumulation in the lesioned striatum in PD animal model | 34 |

| LF-PEG-co-PCL | NAP | Brain | Enhanced brain accumulation with improved memory in AD-induced rats. | 35 |

| LF-NLC- | CUR | Brain | In vivo higher drug accumulation in the brain with regression in AD progression | 36 |

| LF-SLNs- | DTX | Brain | IncreasedinvitroanticancereffectonU-87MG cells with enhanced in vivo biodistribution. | 37 |

| LF/Hyaluronic acid-SLNs | LF/Hyaluronic acid-SLNs | Brain | LF/Hyaluronic acid-SLNs | 52 |

Directly delivering neuroprotective agents or anti-amyloid drugs via nanoparticles has demonstrated potential in reducing amyloid-beta accumulation and mitigating neuroinflammation.33

Parkinson's diseaseDopaminergic therapies delivered through nanoparticles could bypass peripheral metabolism, reduce side effects, and provide targeted brain delivery to affected regions such as the substantia nigra.34

Epilepsy and acute CNS conditionsThe rapid onset of action achievable via nasal delivery is beneficial for managing conditions like seizures, where fast therapeutic intervention is essential.46

Multiple sclerosis (MS)Nanoparticles carrying immunomodulatory agents can help regulate the immune response and potentially reduce the frequency of relapses by delivering drugs directly to the CNS.48

Challenges in nasal drug delivery for neurological disorders and clinical translationBlood–brain barrier (BBB) limitationsAlzheimer's disease (AD) is the sixth leading cause of death in the USA, affecting nearly 5.5 million people. The therapeutic efficacy of these drugs is hindered not only by their reduced concentration in the brain due to the existence of the blood–brain barrier (BBB) but also their low brain permeability.49 This approach increases the bioavailability of the drug in the brain by targeting the olfactory bulb and reduces drug degradation and wastage through systemic clearance.53

Variability in nasal drug absorptionAnatomical differences among patients, mucosal conditions (e.g., nasal congestion), and individual variability in mucociliary clearance can affect absorption efficiency. Addressing these factors is necessary for consistent therapeutic outcomes.53

Safety concerns and long-term effectsThe long-term safety of nanoparticles, especially those with non-biodegradable components, must be evaluated comprehensively. Potential toxicity arising from nanoparticles’ composition, surface charge, and size warrants careful consideration.55

Scalability and manufacturing complexitiesThe large-scale production of nanoparticles with uniform quality and reproducibility poses significant challenges. The discussion highlights the need for standardized manufacturing protocols and quality control measures.56

Regulatory barriersGaining regulatory approval for new nanoparticle formulations can be challenging due to stringent safety, efficacy, and quality requirements. The regulatory landscape for nanomedicine needs to evolve to accommodate novel drug delivery technologies.57

Strategies to overcome limitationsUse of mucoadhesive agents and absorption enhancersIncorporating mucoadhesive polymers or penetration enhancers in nanoparticle formulations can improve drug residence time and uptake in the nasal cavity.47

Stimuli-responsive nanoparticlesDeveloping nanoparticles that respond to specific stimuli (e.g., pH, temperature) in the CNS could enhance targeted drug release and minimize systemic exposure.40

Hybrid nanoparticle systemsCombining different types of materials, such as polymers and lipids, could offer the benefits of both systems, such as improved stability, drug loading capacity, and controlled release.55

Collaborative research and developmentEncouraging collaboration between academia, industry, and regulatory bodies could accelerate the development and approval of novel nanoparticle-based therapies.54

Nanoparticle safety and toxicity evaluationSeveral factors contribute to the cytotoxicity of nanoparticles, as reported by some authors. Some of the author reported that nanomaterials inducing cytotoxicity and because of the substance itself, and some nanoparticles show toxicity without clear mechanism. While some nanomaterials induce cytotoxicity due to their intrinsic properties, others exhibit toxicity without a clear mechanism.57 The CAM assay, widely used for assessing acute toxicity and inflammatory reactions, has proven to be a valuable alternative to the harsh Draize test for evaluating the safety of cosmetics and ocular formulations.44 Notably, certain nanoparticles composed of specific substances are believed to carry a higher risk of toxicity compared to larger particles of the same substance.56 The evaluation of silver nanoparticles (NPs) in terms of toxicology is urgently needed, requiring assessments at both in vitro and in vivo levels. In this study, we aimed to investigate the uptake and intracellular transport of SiNPs with an approximate diameter of 4nm. Utilizing the strong and stable fluorescent signals emitted by SiNPs, we discovered that these small-sized particles initially accumulate at the plasma membrane before being internalized.58 The internalization process primarily occurs through clathrin-mediated and caveolae-dependent endocytosis.59 Interestingly, a smaller proportion of SiNPs are also sorted to the Golgi apparatus. Importantly, our study demonstrates that SiNPs do not exhibit any toxic effects on cell metabolic activity or plasma membrane integrity.60 Overall, Fig. 3 emphasizes the potential of nanomedicine-based nasal drug delivery for efficient, personalized, and minimally invasive treatment options for neurodegenerative diseases and other brain disorders (Fig. 3).

DiscussionRecent advancements in nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems for neurological disorders have focused on utilizing the nasal route to bypass the blood–brain barrier (BBB).53 This route offers a direct pathway to the brain through the olfactory and trigeminal nerves, allowing faster and more targeted drug delivery to the central nervous system (CNS) with fewer systemic side effects.51 Significant progress has been made in optimizing nanoparticle properties to improve drug retention, targeting, and bioavailability within the brain. Functionalized nanoparticles, such as chitosan-coated and PEGylated formulations, enhance mucoadhesion and prolong nasal residence time, increasing drug absorption through the nasal mucosa. These functionalizations also facilitate the crossing of the nasal epithelium and enhance drug delivery to targeted brain regions. Additionally, biodegradable polymers like PLGA and chitosan have been widely adopted for their biocompatibility and ability to control drug release, supporting sustained therapeutic effects. Innovations in encapsulation techniques have enabled the delivery of diverse therapeutics, including small molecules, peptides, and even gene therapies, such as siRNA for neurodegenerative diseases. Such advancements not only improve therapeutic outcomes but also pave the way for diagnostic applications, allowing for real-time monitoring of CNS conditions. These innovations underscore the potential of nanoparticle-based nasal delivery systems as promising solutions for treating neurological disorders.

Conclusion and future prospectiveNanoparticle-based drug delivery via the nasal route holds great potential for overcoming the challenges of treating neurological disorders by bypassing the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and enabling targeted, efficient delivery of therapeutics to the central nervous system (CNS). Advances in nanoparticle design, including surface functionalization and biodegradable polymers, have significantly improved drug retention, bioavailability, and targeted delivery, providing new avenues for effective treatment options for Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and brain cancers.

Looking to the future, continued research in this area is essential to optimize nanoparticle formulations for enhanced precision, sustained release, and biocompatibility. Developing multifunctional nanoparticles that combine therapeutic and diagnostic capabilities could lead to real-time monitoring of disease progression and treatment response. Furthermore, advancements in personalized nanomedicine, where nanoparticles are tailored to an individual's genetic and molecular profile, could offer breakthroughs in customized therapies for complex neurological diseases. While preclinical studies are promising, clinical translation remains challenging. Therefore, addressing regulatory, safety, and large-scale manufacturing issues will be crucial in advancing these technologies from the lab to clinical settings. With continued innovation, nanoparticle nasal delivery systems may soon transform the landscape of neurological disorder treatment, providing more effective, targeted, and minimally invasive solutions.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.