Numerous studies have addressed the impact of multiple sclerosis (MS) on patients’ work.1 Most of these approach the question from a solely economic perspective, however: they calculate the number of days per year patients are absent from work due to MS and the indirect costs associated with work-related problems, and analyse the relationship between the level of disability (EDSS) and total cost due to MS.1,2 In contrast, few studies address the specific professional difficulties facing MS patients and how these problems are perceived.3 Furthermore, these studies use non-validated instruments, tools not specifically designed to evaluate work-related problems, or instruments that evaluate a limited set of difficulties.1,3

The Multiple Sclerosis Work Difficulties Questionnaire is a self-administered instrument evaluating the impact of MS on patients’ professional lives; both the original 50-item version and the more recently developed shorter version (MSWDQ-23) have good psychometric properties.4,5 Both were initially developed in English by a group of neuropsychologists from the University of New South Wales (Australia). The MSWDQ-23 contains 23 items with 5 response options (from 0 [never] to 10 [almost always]), which assess how frequently patients experienced difficulties in their current or most recent jobs over the previous 4 weeks. Items are grouped into 3 dimensions: physical, psychological/cognitive, and external barriers. The total scores for each dimension and for the questionnaire as a whole range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating greater difficulty. Patients’ perception of cognitive barriers in the workplace, as measured with the MSWDQ-23, has been reported to be predictive of unemployment and reduced work hours since MS diagnosis.6

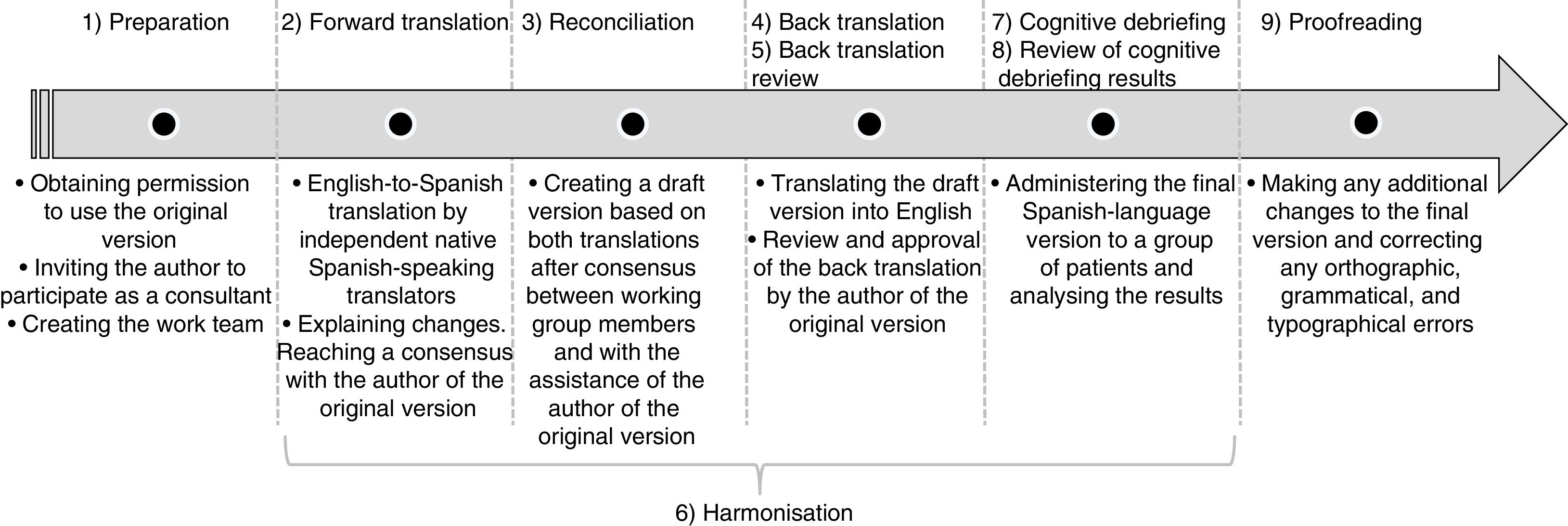

We describe the process of cultural adaptation of the MSWDQ-23 to the Spanish-speaking population. The adaptation followed the recommendations made by the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research7: (1) preparation, (2) forward translation, (3) reconciliation, (4) back translation, (5) back translation review, (6) harmonisation, (7) cognitive debriefing, (8) review of cognitive debriefing results, and (9) proofreading (Fig. 1).

Two independent native Spanish-speaking translators independently translated the questionnaire; the project coordinator subsequently reconciled the 2 translations with the assistance of the translators. The Spanish-language version introduced some language changes in the instructions and response options to make sentences flow well. The term “workplace” was translated as “su trabajo” (your job). Although “por favor” (please) is not commonly used in Spanish when giving instructions, we decided to preserve the expression but did not repeat it in subsequent sentences. In the final sentence of the instructions, the expression “describing you” was translated as “en su caso” (in your case) rather than literally. The response option “rarely” was translated as “pocas veces” (literally “few times”), as in many other questionnaires. Minor changes were introduced to adapt sentences to colloquial Spanish. The words “employer” and “manager” were translated as “jefe” (boss). The expression “tolerate the temperature” was translated as “aguantar la temperatura” (cope with the temperature), since the term “tolerar” is more formal in Spanish and has a slightly different connotation than in English. The word “struggle” was changed for the expression “me ha costado” (I found it difficult). Item 20 (“I feared that I would be incontinent”) was the item with the greatest change since the adjective “incontinente” is rarely used in this context in Spanish; the sentence was rephrased to use the noun “incontinencia” (incontinence) and the verb “fear” was translated as the more natural expression “sentir temor” (to be afraid of). A native English-speaking translator participated in back translation and back translation review, using the Spanish-language version resulting from the reconciliation process. No significant differences were observed between the 2 translations; the first Spanish-language version agreed by all members of the research group was therefore used. The entire cultural adaptation process included a process of harmonisation, which involved active exchange of opinions between members of the research group; this stage constitutes a continuous quality control system to preserve concordance between the Spanish- and English-language versions. For the cognitive debriefing and the review of cognitive debriefing results, the Spanish-language version of the MSWDQ-23 was administered to 10 native Spanish-speaking patients with MS. This step is essential to ensure a good level of comprehension by the target population and to identify any potential sources of confusion. Mean age in the sample was 41.5±11.4 years. Participants were predominantly women (80%) and had mainly completed primary and secondary education. All participants completed the questionnaire and none reported difficulty understanding any item, expression, or term. Some minor suggestions were made during the interviews. Contrary to the decision made during reconciliation, some patients preferred the expression “tolerar la temperatura” (tolerate the temperature), the literal translation of the English-language version, over “aguantar la temperatura”. Item 12 (“He temido no ser capaz de mantenerme si no podía seguir trabajando”; I feared that I would not be able to support myself if I could no longer work) was not clear enough for some patients, so we decided to add the word “económicamente” (financially). These changes were incorporated to create the second Spanish-language version of the questionnaire. Finally, the project coordinator verified that there were no typographical, orthographic, or grammatical errors in the final version. The process of cultural adaptation of the MSWDQ-23 concluded after this final review, which produced the definitive version of the questionnaire for the Spanish-speaking population (Table 1).

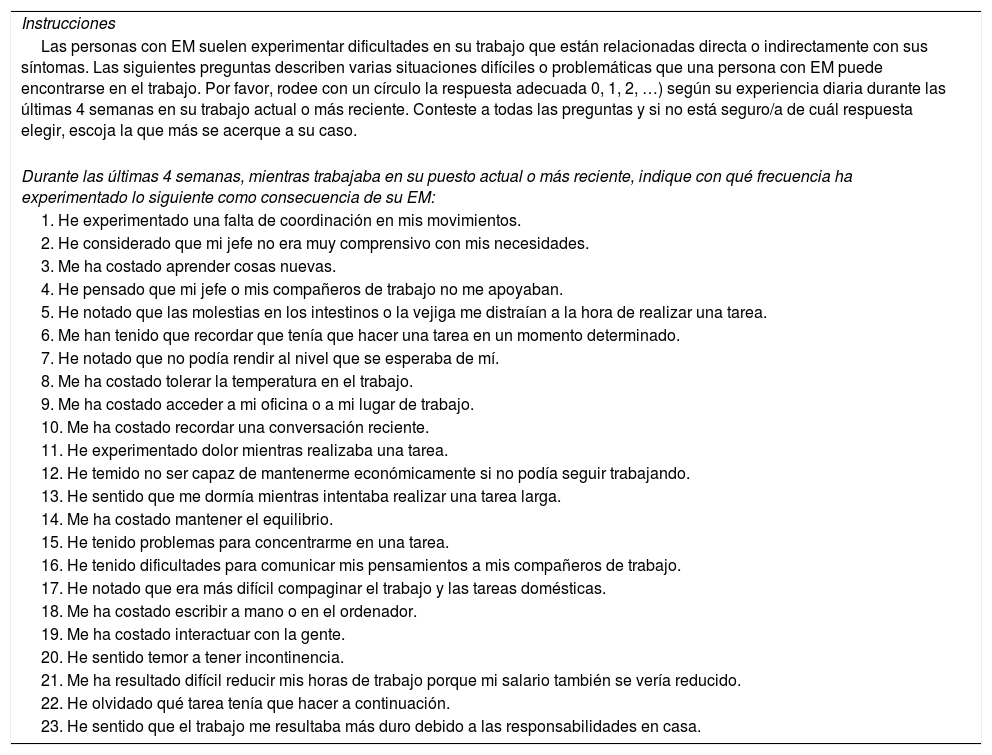

Final Spanish-language version of the MSWDQ-23.

| Instrucciones |

| Las personas con EM suelen experimentar dificultades en su trabajo que están relacionadas directa o indirectamente con sus síntomas. Las siguientes preguntas describen varias situaciones difíciles o problemáticas que una persona con EM puede encontrarse en el trabajo. Por favor, rodee con un círculo la respuesta adecuada 0, 1, 2, …) según su experiencia diaria durante las últimas 4 semanas en su trabajo actual o más reciente. Conteste a todas las preguntas y si no está seguro/a de cuál respuesta elegir, escoja la que más se acerque a su caso. |

| Durante las últimas 4 semanas, mientras trabajaba en su puesto actual o más reciente, indique con qué frecuencia ha experimentado lo siguiente como consecuencia de su EM: |

| 1. He experimentado una falta de coordinación en mis movimientos. |

| 2. He considerado que mi jefe no era muy comprensivo con mis necesidades. |

| 3. Me ha costado aprender cosas nuevas. |

| 4. He pensado que mi jefe o mis compañeros de trabajo no me apoyaban. |

| 5. He notado que las molestias en los intestinos o la vejiga me distraían a la hora de realizar una tarea. |

| 6. Me han tenido que recordar que tenía que hacer una tarea en un momento determinado. |

| 7. He notado que no podía rendir al nivel que se esperaba de mí. |

| 8. Me ha costado tolerar la temperatura en el trabajo. |

| 9. Me ha costado acceder a mi oficina o a mi lugar de trabajo. |

| 10. Me ha costado recordar una conversación reciente. |

| 11. He experimentado dolor mientras realizaba una tarea. |

| 12. He temido no ser capaz de mantenerme económicamente si no podía seguir trabajando. |

| 13. He sentido que me dormía mientras intentaba realizar una tarea larga. |

| 14. Me ha costado mantener el equilibrio. |

| 15. He tenido problemas para concentrarme en una tarea. |

| 16. He tenido dificultades para comunicar mis pensamientos a mis compañeros de trabajo. |

| 17. He notado que era más difícil compaginar el trabajo y las tareas domésticas. |

| 18. Me ha costado escribir a mano o en el ordenador. |

| 19. Me ha costado interactuar con la gente. |

| 20. He sentido temor a tener incontinencia. |

| 21. Me ha resultado difícil reducir mis horas de trabajo porque mi salario también se vería reducido. |

| 22. He olvidado qué tarea tenía que hacer a continuación. |

| 23. He sentido que el trabajo me resultaba más duro debido a las responsabilidades en casa. |

During cultural adaptation, we detected no significant translation or comprehension difficulties that forced us to make major changes in the content of any item; this may be explained by the fact that items are short and simple and refer to very specific and common workplace situations. The number of patients included in the last phase is higher than that recommended by the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research, although the sample could have been more representative in terms of sex and education level. However, the fact that most participants had secondary studies ensures that the final version of the questionnaire is understandable for patients with higher levels of education. We can conclude that the Spanish-language version of the questionnaire is fully equivalent to the English-language version in terms of item content.

Using an appropriate methodology during the process of cultural adaptation is particularly relevant in a context where the results of patient-centred measures are becoming increasingly important for the approval of new therapies and are used by healthcare authorities to evaluate the benefits of certain treatments.7–9

The cultural adaptation of the MSWDQ-23 to the Spanish-speaking population constitutes the first step in evaluating the impact of MS on patients’ professional lives. A psychometric validation of the questionnaire's properties (feasibility, validity, reliability, sensitivity to change) should be conducted in a Spanish-speaking population to confirm that the Spanish-language version is equivalent to the original questionnaire. The Spanish-language version of the MSWDQ-23 presented here is currently under validation in the Spanish population.

FundingThis study was sponsored by the medical department of Roche España.

Conflicts of interestMònica Sarmiento works for QuintilesIMS and Jorge Maurino belongs to the medical department of Roche España. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Martínez-Ginés ML, García-Domínguez JM, Sarmiento M, Maurino J. Adaptación cultural al español del cuestionario sobre las dificultades para trabajar con esclerosis múltiple. Versión corta de 23 ítems (MSWDQ-23). Neurología. 2019;34:611–614.