Radical or extended thymectomy is an effective treatment for myasthenia gravis in the adult population. There are few reports to demonstrate the effectiveness of this treatment in patients with juvenile myasthenia gravis.

ObjectiveThe main objective of this study was to show that extended transsternal thymectomy is a valid option for treating this disease in paediatric patients.

ResultsTwenty-three patients with juvenile myasthenia gravis underwent this surgical treatment in the period between April 2003 and April 2014; mean age was 12.13 years and the sample was predominantly female. The main indication for surgery, in 22 patients, was the generalised form of the disease (Osserman stage II) together with no response to 6 months of medical treatment. The histological diagnosis was thymic hyperplasia in 22 patients and thymoma in one patient. There were no deaths and no major complications in the postoperative period. After a mean follow-up period of 58.87 months, 22 patients are taking no medication or need less medication to manage myasthenic symptoms.

ConclusionsExtended (radical) transsternal thymectomy is a safe and effective surgical treatment for juvenile myasthenia gravis.

La timectomía radical ampliada para el tratamiento de la miastenia gravis es una opción efectiva en la población adulta. No ocurre lo mismo en el caso de la miastenia gravis juvenil, ya que existen pocos reportes que demuestren su efectividad.

ObjetivoEl principal objetivo de esta investigación fue el de demostrar que la timectomía transesternal radical ampliada es una alternativa validada para el tratamiento de esta enfermedad en este grupo de pacientes.

ResultadosCon esta técnica fueron intervenidos 23 pacientes con miastenia gravis juvenil en el periodo comprendido entre abril del 2003 y abril del 2014. La edad media fue de 12,13 años y hubo un predominio en el sexo femenino. La principal indicación quirúrgica fue, en 22 pacientes, la forma generalizada de la enfermedad (estadio ii de Osserman) sin respuesta al tratamiento médico luego de 6 meses. El diagnóstico histológico fue de hiperplasia tímica en 22 pacientes y timoma linfocítico tipo i en un paciente. No hubo fallecidos y no se presentaron complicaciones mayores en el periodo postoperatorio. Con un seguimiento medio de 58,87 meses, 22 pacientes se encuentran sin tratamiento o necesitando menor cantidad de medicamentos para el control de los síntomas miasténicos.

ConclusionesLa timectomía transesternal ampliada es una opción segura y efectiva para el tratamiento quirúrgico de la miastenia gravis juvenil.

Juvenile myasthenia gravis (JMG) is an autoimmune disorder of unknown aetiology. In JMG, serum antibodies alter neuromuscular transmission when they bind to acetylcholine receptors located in the muscular membrane at the motor end plate. This results in premature muscle fatigue progressing to paralysis during muscle contraction. The incidence of myasthenia gravis (MG) during the first 18 years of life is 4 cases per 100000 population. The most frequent forms are juvenile MG (18%), transient neonatal MG (1.5%), and congenital MG. JMG manifests with generalised myasthenia (47%), ocular myasthenia (43%), and myasthenic crises (10%). After 1 to 3 years, generalised myasthenia accounts for 80% of all manifestations, whereas ocular myasthenia drops to 20% and myasthenic crises, which only occur in the context of generalised mysathenia, decrease to 5%.1–5 The thymus has been suggested as a possible site of origin given that 75% of patients older than 20 have thymic abnormalities, 85% display thymic hyperplasia with active germinal centres, and 15% have thymomas. In addition, thymectomy improves patients’ outcomes in most cases. Acetylcholine receptors in thymic myoid cells may act as autoantigens and trigger an immunological reaction at the level of the thymus. Thymic CD4+ T-cells stimulate serum B-cells, which in turn will start producing antibodies against acetylcholine receptors.6,7

JMG is pathophysiologically heterogeneous. In most cases, it is associated with presence of acetylcholine receptor antibodies. However, it has also been reported to be associated with anti-MuSK antibodies and some cases are considered ‘seronegative’ since no antibodies can be detected using currently available techniques. Therefore, diagnosis of the disease is not based solely on antibody detection. The patient's clinical profile and such neurophysiological studies as repetitive nerve stimulation and especially jitter analysis play an important role in diagnosing the disease. Pharmacological tests are also useful. Treatment for JMG is symptomatic and aetiological. In patients with generalised involvement and incomplete response to treatment, a wide range of therapeutic measures are applied to halt the autoimmune response, including thymectomy, immunosuppresant agents, plasmapheresis, and immunoglobulins.6,8–14 Despite the controversy surrounding treatment for MG, surgery has been shown to be superior to medical treatment alone, even in cases of JMG.12,13,15–22 The main purpose of our study was to confirm the validity of radical or extended transsternal thymectomy for the treatment of JMG.

Patients and methodsStudy characteristicsWe conducted a prospective non-experimental study including 23 patients diagnosed with JMG who underwent extended thymectomy between April 2003 and April 2014. The study was conducted in the cardiac surgery department at Cardiocentro Ernesto Guevara and the Neurology Department at Hospital Pediátrico Provincial, in Santa Clara, Cuba.

ProcedureWe used the criteria by Cheng et al.21 for diagnosing JMG, indicating extended thymectomy, and assessing patients’ outcomes; the clinical criteria by Osserman and Genkins14 for classifying MG; imaging criteria (chest radiography, CT) to rule out thymoma; neurophysiological criteria (repetitive nerve stimulation, single-fibre EMG); and pharmacological criteria (Tensilon test).

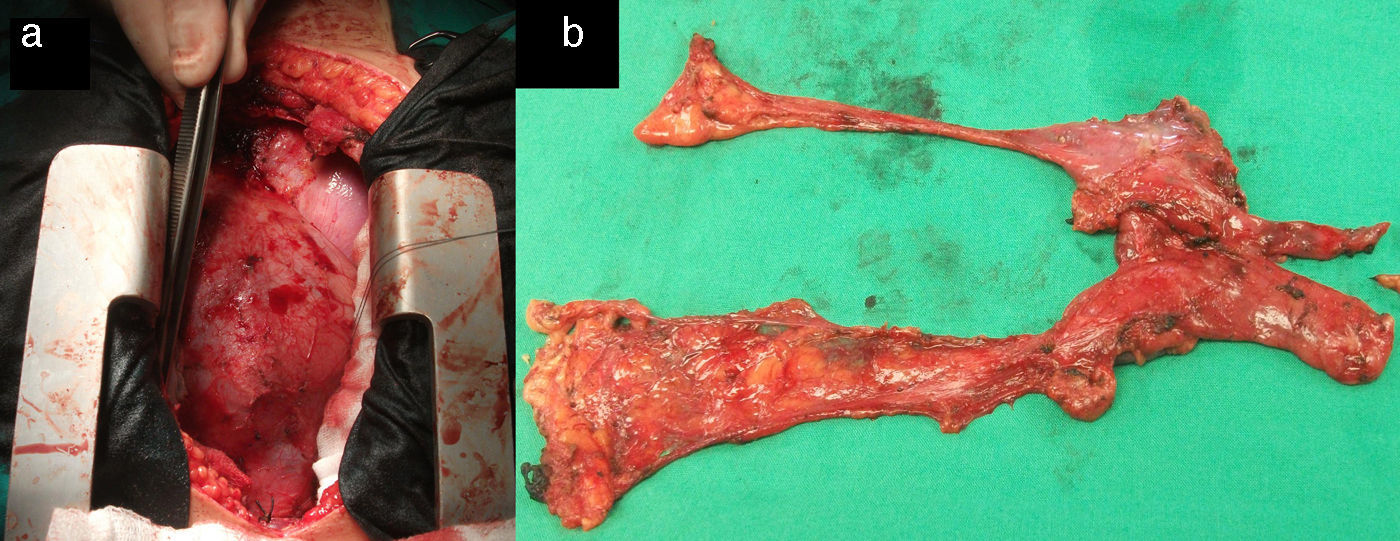

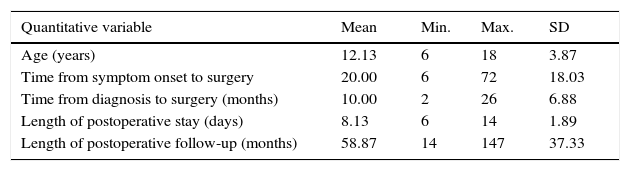

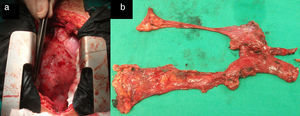

Surgical treatment consisted of extended transsternal thymectomy,20 which involves resection of the thymus, mediastinal pleura, and fibrofatty connective tissue extending from the diaphragm to the thyroid between the phrenic nerves (Fig. 1a and b). Surgery was indicated based on the following criteria21: resistance to pyridostigmine or immunosuppressant treatment, generalised myasthenia with no signs of improvement after 6 months of medical treatment, ocular myasthenia with partial response to pyridostigmine, and lack of stable, complete remission for more than 2 years. Before undergoing thymectomy, all patients started treatment with intacglobin dosed at 400mg/kg and administered in 5 doses (3 before and 2 after surgery).

VariablesWe recorded the following variables for each patient: age, sex, Osserman stage, symptom onset, date of diagnosis, date of surgery, time elapsed between symptom onset and surgery (in months), time elapsed between diagnosis and surgery (in months), preoperative treatment, postoperative complications, length of stay in the intensive care unit, total length of postoperative hospital stay, complications, histological diagnosis, total postoperative follow-up time (in months), and surgery outcomes (at 1, 3, and 5 years). Patient were classified in 4 outcome groups21: taking no medication, taking less medication and displaying improvements, taking less medication and displaying no improvements, and experiencing exacerbation.

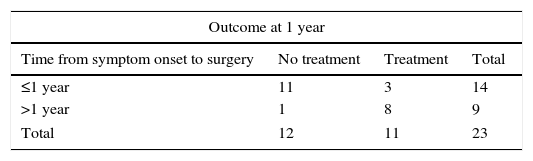

We investigated the impact of time from symptom onset to surgery on outcomes.

Statistical analysisWe used SPSS statistical software version 15 for Windows for data processing and statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics were used for all variables. Quantitative variables were expressed as means±SD and qualitative variables as absolute values and percentages. The analysis was intended to determine whether time between symptom onset and surgery had an impact on surgical outcomes. Statistical significance for this correlation was calculated using the Fisher exact test. Qualitative variables were said to be correlated for values of P≤.05.

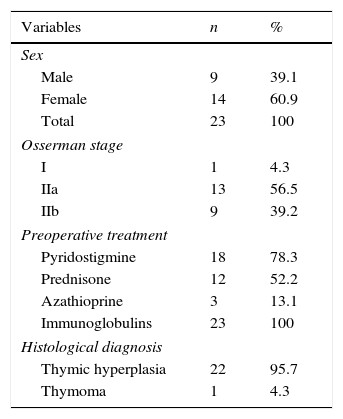

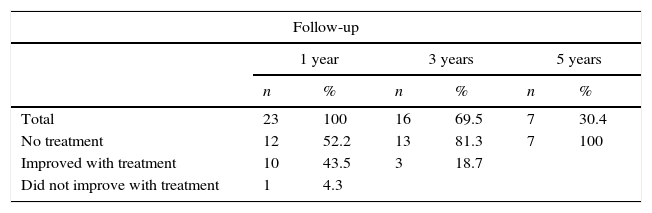

ResultsTable 1 summarises the studied quantitative variables. Mean age of our sample was 12.13 years. The mean postoperative follow-up time was 58.87 months. Mean time from symptom onset to surgery was 20 months and mean time from diagnosis to surgery was 10 months. The mean length of the postoperative hospital stay was 8.3 days. Female patients accounted for 6.9% of the sample; the most frequent Osserman stage was stage II. Histology studies indicated thymic hyperplasia in 22 patients and type 1 lymphocytic thymoma in one; thymic remnants were found in 3 patients (Table 2). In the patient with thymoma, JMG had manifested with ocular myasthenia when she was 10; 2 years later, she displayed generalised involvement and bulbar symptoms. None of the patients died; they all were extubated within the first 6 hours and stayed in the intensive care unit for less than 48 hours. None of the patients experienced myasthenic crises during the postoperative period. The only postoperative complication was pleural effusion in one patient; fluid was removed by pleural puncture. During the postoperative period, the dose of parasympathomimetics was reduced and the associated adverse effects were monitored. All patients received medical treatment for 6 months after surgery; after that period, the doses and number of drugs were reduced. We should point out that, at one year of follow-up, 95.6% of the patients received either no medication or lower doses to control symptoms; at 3 years, this percentage had risen to 100% (Table 3). Table 4 shows the influence of time between symptom onset and surgery on surgery outcomes. Time from symptom onset to surgery was less than one year in 12 patients and more than one year in 11. Eleven of the former and only one of the latter received no medication one year after thymectomy. The Fisher exact test (P=.003) shows that outcomes of extended thymectomy are significantly better when time between symptom onset and surgery is less than one year.

Distribution of patients according to the studied quantitative variables.

| Quantitative variable | Mean | Min. | Max. | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 12.13 | 6 | 18 | 3.87 |

| Time from symptom onset to surgery | 20.00 | 6 | 72 | 18.03 |

| Time from diagnosis to surgery (months) | 10.00 | 2 | 26 | 6.88 |

| Length of postoperative stay (days) | 8.13 | 6 | 14 | 1.89 |

| Length of postoperative follow-up (months) | 58.87 | 14 | 147 | 37.33 |

Source: Department of Statistics.

Patient distribution by sex and other qualitative variables.

| Variables | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 9 | 39.1 |

| Female | 14 | 60.9 |

| Total | 23 | 100 |

| Osserman stage | ||

| I | 1 | 4.3 |

| IIa | 13 | 56.5 |

| IIb | 9 | 39.2 |

| Preoperative treatment | ||

| Pyridostigmine | 18 | 78.3 |

| Prednisone | 12 | 52.2 |

| Azathioprine | 3 | 13.1 |

| Immunoglobulins | 23 | 100 |

| Histological diagnosis | ||

| Thymic hyperplasia | 22 | 95.7 |

| Thymoma | 1 | 4.3 |

Source: Department of Statistics.

JMG can be classified as prepubertal (symptoms appear before puberty) or pubertal/postpubertal (symptoms manifest during or after puberty). Both subtypes have distinctive clinical characteristics. Prepubertal JMG is commonly linked to ocular involvement and affects both sexes equally, whereas pubertal and postpubertal JMG affects females predominantly and its prognosis is better due to greater likelihood of spontaneous remission. In adult MG, over 80% of the cases of ocular myasthenia progress to generalised myasthenia; in JMG, however, progression to generalised myasthenia is less frequent, especially in the prepubertal form.6,22,23,25–29 In our sample, 7 patients (30.4%) had prepubertal JMG and 16 (69.6%) postpubertal JMG; at time of surgery they all had generalised myasthenia. Most patients were female.

Remission may occur spontaneously or after a period of medical treatment, especially in patients with prepubertal JMG.23–26 However, all patients diagnosed with prepubertal JMG and followed up during the 1990s in the neurology department at Hospital Pediátrico Provincial continued to receive medication to control myasthenic symptoms upon reaching puberty. The likelihood of remission is also influenced by ethnicity.6,21–23 The thymus is known to play a major role in the aetiopathogenesis of JMG. Thymectomy constitutes a valid treatment option since the disappearance of thymic germinal centres halts antibody production and diversification.30,31 According to Gronseth and Barohn,32 patients with nonthymomatous autoimmune MG have a greater probability of symptom remission or improvement. More recent review articles including patients with prepubertal JMG report increased remission rates after thymectomy.33,34 Special attention should be paid to young children; the probability of remission is most frequent in this population. The youngest patient in our series was 6. We should also mention purely ocular JMG: in these cases, thymectomy has not been demonstrated to prevent generalised progression and should therefore only be used in patients refractory to medical treatment.21,27 Only one patient in our sample had ocular JMG at the time of surgery. Surgery was indicated in this case since the patient had experienced no improvements after a year of medical treatment and a CT scan revealed that the thymus had doubled in size compared to a CT scan performed a year previously. Another reason for considering thymectomy as a treatment option for JMG is the actual possibility that myasthenic symptoms may be due to presence of a thymoma even when CT images display a morphologically normal thymus. This was the case of the patient who was histologically diagnosed with type 1 lymphocytic thymoma after thymectomy.

There are several routes of access for thymectomy. Evidence shows that outcomes are independent of the route of access if the thymus and fibrofatty tissue are fully resected.16–22 Bulkey et al.20 and Masaoka et al.19 began conducting simple cervicomediastinal and transsternal thymectomies and subsequently performed extended transsternal thymectomies that achieved higher remission rates. According to the literature, surgery outcomes may last up to 5 years after extended thymectomy and remission rates show a significant correlation with time from symptom onset to surgery.16–22,33,34 For this reason, we decided to treat our patients with extended thymectomy after a 6-month period of medical treatment failed to achieve remission of myasthenic symptoms. Another factor affecting outcome is the surgical technique used. Extended thymectomy has been shown to be superior to conventional thymectomy since it achieves complete resection of tissues potentially containing thymic remnants, which may be responsible for non-remission after surgery. Similar results have been published by Essa et al.22 and Cheng et al.21: after extended thymectomy, 90% and 91.1% of the patients required either no treatment or lower doses to control myasthenic symptoms. Despite published evidence that video-assisted thoracoscopic thymectomy is effective, there is no consensus on the best route of access for extended thymectomy.15,17 Our results indicate that extended transsternal thymectomy is a safe and effective treatment option for JMG.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Vázquez-Roque FJ, Hernández-Oliver MO, Medrano Plana Y, Castillo Vitlloch A, Fuentes Herrera L, Rivero-Valerón D. Resultados del tratamiento quirúrgico en la miastenia gravis juvenil. Neurología. 2017;32:137–142.