Dear Editor:

Marchiafava–Bignami disease was first described in 1903 by 2 neuropathologists who observed that 3 alcoholic patients had presented acute symptoms of psychomotor agitation, seizures, and decreased level of consciousness, followed by death. Neuropathological studies revealed that these patients exhibited demyelination and atrophy of the corpus callosum.1 Since then, short series have provided additional information about this disease. It appears in the sudden-onset form described by Marchiafava and Bignami, and also in a chronic form characterised by signs of interhemispheric disconnection, sensory hemispatial neglect, and signs of alien limb syndrome. These signs are frequently associated with cognitive impairment and sometimes coincide with Korsakoff syndrome, which is another common finding in alcoholic patients.2–4

Pathophysiology of the disease has been attributed to numerous types of ischaemic lesions and demyelination of the corpus callosum in both the acute-onset and progressive varieties. It is often associated with vitamin B12 and folic acid deficits, alcoholism, and hyporexia of any aetiology. Many patients with this disease present cognitive impairment with a potentially reversible cause, which highlights the importance of early diagnosis and treatment.5–9 In this article, we describe 2 cases with unusual presentations (1 acute, the other chronic) and provide a review of medical literature.

The first patient was a female aged 74 with a history of controlled mild arterial hypertension, hypothyroidism, and dyslipidaemia. She had no history of alcoholism or malnutrition, performed activities of daily living independently, and her prior cognitive state appeared to be normal. The patient came to the emergency department due to disorientation in time and space, anomic aphasia in spontaneous conversation, anterograde amnesia, and a mild headache over the previous 6hours.

Upon admission, the patient's status was afebrile and good overall, although blood pressure was 140/85mmHg. Neurological examination showed that the patient was disoriented in time and space, with no meningeal signs or motor deficits. Cranial nerves were normal and superficial sensitivity was intact. Plantar cutaneous reflexes exhibited bilateral flexion; gait and coordination were normal. We detected left sensory hemispatial neglect (sensory extinction).

The cranial CT performed in the emergency department revealed a haematoma of the splenium of the corpus callosum (Fig. 1). Brain MRI with MR angiography ruled out expansive lesions and arteriovenous malformations; last of all, conventional arteriography excluded AVM and other lesions. EEG showed slow left temporal intermittent theta activity (TIRTA). Analyses did not initially show any relevant abnormalities; folate and vitamin B12 levels were acceptable. Neuropsychological examination showed mild cognitive impairment with a dysexecutive component.

Clinical evidence of left hemispatial neglect remained 8 months later, with neuropsychological tests showing few changes. A new routine brain MRI showed multiple ischaemic lesions in the splenium of the corpus callosum and an area of the splenium with haematoma reabsorption. Laboratory tests showed a vitamin B12 deficit. Medical history and physical examination revealed hyporexia and loss of 8kg in 6 months. According to the family, the patient had experienced periods of apparently psychogenic hyporexia over the past few years and was under psychiatric study.

The second patient, a 62-year-old female, was admitted for convalescence and functional recovery following knee prosthesis surgery. Her medical history included bariatric surgery 5 years before which was indicated due to morbid obesity. Weight loss in the 3 years prior to knee surgery amounted to 55kg. Despite resolution of obesity, the patient became progressively housebound and gave up her habitual activities, citing her chronic degenerative arthropathy (right knee pain) as the motive. The patient also displayed frequent forgetfulness, repetitive conversations, and difficulty getting dressed and using kitchen implements (apraxia), including “not knowing how” to cut bread. Physical examination showed an involuntary creeping movement in her left arm which the patient did not notice, although family members said it had been present for several months. This movement was suggestive of alien limb syndrome. Results for cranial nerves and muscle strength were normal, as were superficial and deep-tissue sensitivity, even though the patient displayed patent left hemispatial neglect.

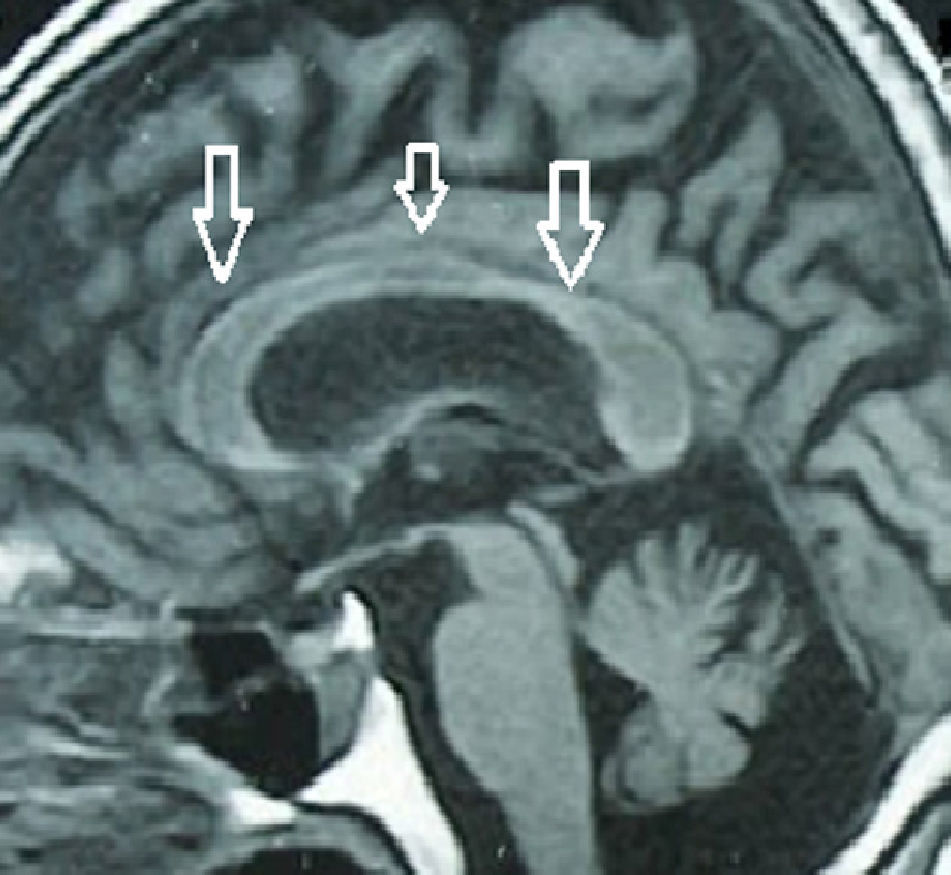

Cognitive assessment yielded an MMSE score of 26/30 (2 amnestic errors and 2 executive errors). We performed a brain MRI that showed multiple confluent infarcts in the splenium of the corpus callosum (Fig. 2). EEG revealed left temporal intermittent rhythmic theta activity (TIRTA), and the analysis detected low vitamin B12 and folic acid levels. We started the patient on intramuscular vitamin B12 and folic acid. While hospitalised, the patient experienced 3 right-sided motor simple partial seizures with secondary generalisation. As a result, she was treated with antiepileptic drugs (levetiracetam IV), and symptoms resolved completely.

Three months later, the patient's executive functions showed definite improvement (she was able to dress herself and complete daily activities that had previously exceeded her abilities). She continued experiencing difficulties with drawing tasks (clock drawing test and pentagon copying). MMSE score was 27/30. We observed no involuntary movements of the left arm, no sensory hemineglect, and no agnosia. Routine laboratory tests showed normal folic acid and vitamin B12 levels.

Marchiafava–Bignami syndrome is defined as primary degeneration of the corpus callosum associated with chronic alcohol consumption and other situations eliciting nutritional deficiencies.10 Consensus holds that the disease is due to a deficiency in vitamin B12 and folate, since many patients recover upon taking these supplements.

We present 2 clinical cases, one with acute onset (first case) and the other with a chronic onset (second case); both show unusual forms of presentation. The case with acute onset began with a haemorrhagic infarct in the splenium of the corpus callosum. Progression was very benign despite the presence of a large cerebral haematoma, and the patient presented only a few symptoms, including hemispatial neglect and anomic aphasia. The other case, the one with gradual onset, manifested with slow, progressive cognitive impairment with frank apraxia and amnestic deficit. One remarkable feature was alien limb syndrome, which is related to the interhemispheric disconnection that occurs in cases of corpus callosum injury, according to earlier descriptions.11 Regarding aetiology, neither of the patients had a history of alcoholism, although both had nutritional deficits. The patient with acute onset had lost 10kg in 3 months in association with depression and very low levels of vitamin B12 and folic acid. In the second case, the patient underwent bariatric surgery to correct morbid obesity. After the procedure, she experienced progressive cognitive decline with memory loss and apraxia. Many patients with vitamin and/or folic acid deficiency may present cognitive impairment similar to Wernicke–Korsakoff syndrome, which is frequent in alcoholics. Nevertheless, the corpus callosum lesions viewed by MRI in both cases, plus the presence of clear signs of interhemispheric disconnection, were sufficient to distinguish between cognitive impairment caused by Wernicke–Korsakoff and CI caused by MB.

To the best of our knowledge, there are few published cases of patients with Marchiafava–Bignami disease secondary to bariatric surgery. We do not know if vitamin B12 and folic acid deficiencies are common in these patients, but we recommend performing neuropsychological assessments and measuring plasma levels of these dietary minerals at the slightest clinical sign of a deficiency in these patients.

Our patients demonstrated asymmetrical temporal intermittent rhythmic theta activity. One of our patients presented partial seizures with secondary generalisation and therefore had to be treated with antiepileptic drugs. Epileptic seizures have been described repeatedly in patients with MB; in fact, the initial cases described by Marchiafava and Bignami in 1903 included epileptic seizures.

Regarding pathophysiological changes, we believe that the lesions in these patients are demyelinating and ischaemic. Vitamin deficiency probably elicits small vessel necrosis, which in turn causes loss of white matter and atrophy of the corpus callosum. Nevertheless, demyelination may extend to other areas of the brain.6

Lastly, we conclude that the disease described by Marchiafava and Bignami is a clinical syndrome that may be seen in non-alcoholic patients. Its most important feature is poor absorption of vitamin B12 and folic acid, which elicits secondary demyelination. Doctors should carefully examine patients with prolonged hyporexia and those undergoing bariatric surgery for any reason, since they may experience poor vitamin absorption and demyelinating lesions of the corpus callosum.

Please cite this article as: Salazar G, Fragoso M, Español G, Cuadra L. Degeneración primaria del cuerpo calloso (Marchiafava-Bignami): 2 formas inusuales de presentación clínica. Neurología. 2013;28:587–589.