CADASIL (cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy) is a disorder caused by a mutation of the NOTCH 3 gene, which is located in chromosome 19. It is characterized by: recurrent strokes without any associated vascular risk factors; mood disturbances; migraine (often accompanied by aura); and progressive dementia.1 MRI imaging shows cerebral white matter hyperintensity, particularly in the external capsule and the temporal pole.2 CADASIL is typically associated with the presence of missense mutations related to cysteine residue in the 34 EGFr extracellular domains of the NOTCH3 protein (N3ECD). Although NOTCH3 mutation locations may vary considerably, they tend to correlate with disease severity and consistently affect the cysteine balance within extracellular NOTCH3.3 Deposits of granular osmiophilic material (GOM) around blood vessels are also a unique feature of CADASIL and appear to play a role in sequestering proteins that are essential for blood vessel homeostasis.4 Reversible encephalopathy tends to be the first sign of disease in up to 10% of cases associated with migraine.5 However, its pathogenesis and prognosis are still currently unknown. Here, we describe the case of a patient without a history of migraine history whose CADASIL had an encephalopathic debut.

A 38-year-old man, who was a smoker without a history of migraine, was admitted to the urology department for the drainage of a perineal abscess, under general anesthetic. His family history included the death of his father due to progressive multiple sclerosis accompanied by cognitive impairment. After surgery, the patient presented mild bradypsychia and reported right-facial hemihypoesthesia. On the 5th postoperative day, he began to show signs of rapidly progressive dysarthria, left dysmetria and severe bradypsychia. The patient was hemodynamically stable but with a tendency to hypotension (mean BP 90/60). In the following hours, the symptoms rapidly worsened, with the patient suffering headaches, left hemianopsia, mutism and a reduced level of alertness (Glasgow 11), for which he was transferred to the intensive care unit. Once there, and considering the possibility of either vasculitis of the central nervous system or of a demyelinating illness, he was administered 5 boluses of 1g methylprednisolone, but without any noticeable improvement. On day 10, given his clinical stability, the patient was transferred to the neurology ward to continue the diagnostic process and begin recovery. On exploration, we subsequently observed mutism, with right facio-brachio-crural hemiparesis and left dysmetria (NIHSS 22). On day 30, given the positive clinical evolution at the urological and neurological levels, we decided to discharge the patient and to provide homebased physiotherapy. On discharge from hospital, the patient still had moderate dysarthria, right brachial and femoral hemiparesis, and left-side hemiataxia (NIHSS 5). The patient was able to stand and walk with support (using a walking frame). Important alterations of mood/behavior were also evident.

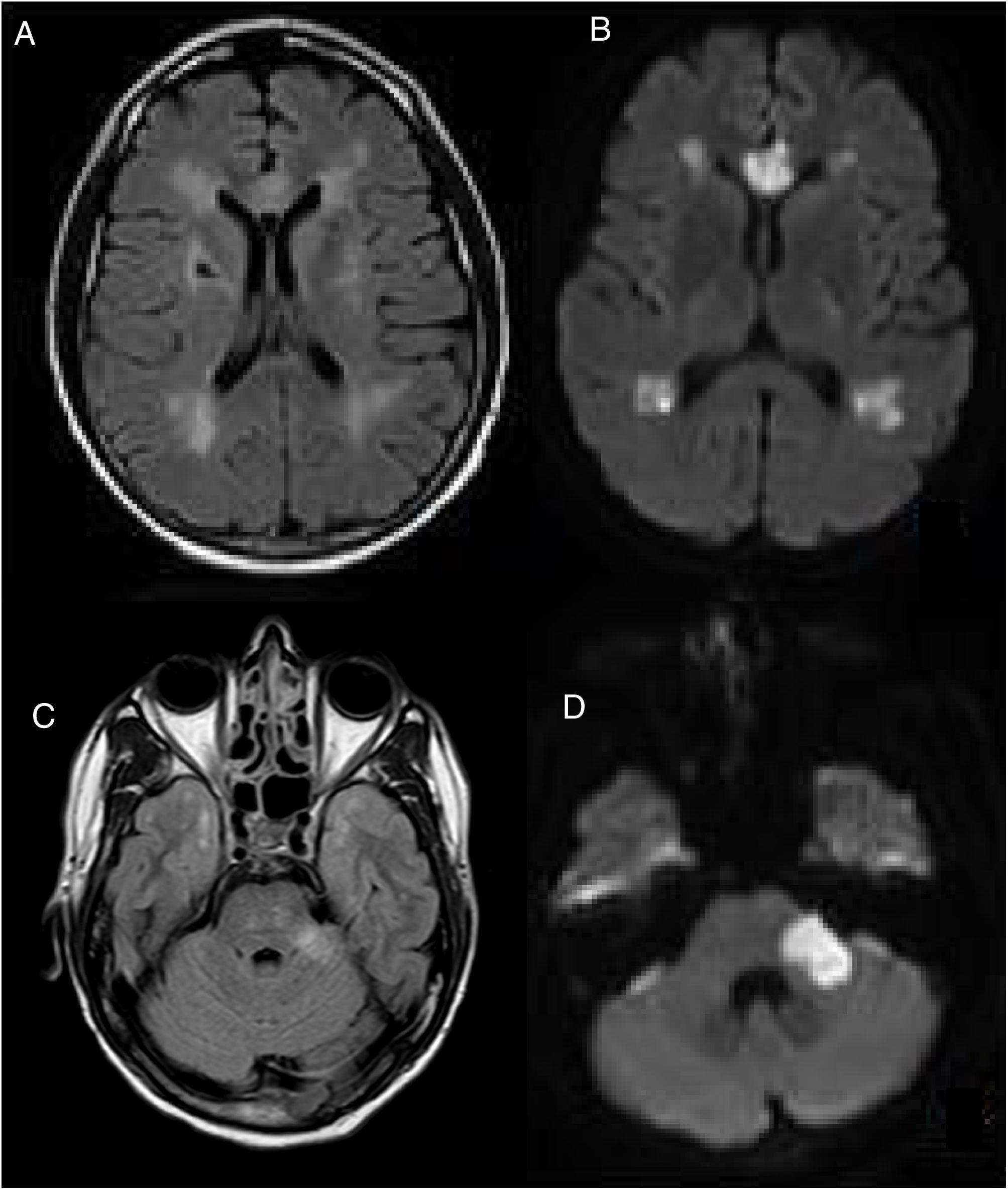

A cranial MRI scan was performed on day 5, which showed chronic ischemic lesions in the thalamus and at the right capsule-lenticular level. There were also signs of hyperintensity in the temporal pole (O'Sullivan's sign) and acute/subacute ischemic lesions in the supratentorial white matter, corpus callosum and left cerebellar peduncle (Fig. 1).

CEREBRAL MRI, (A–C) FLAIR and (B–D) DWI, performed on the 5th postoperative day. Multiple acute and subacute ischemic lesions were observed at the level of the supratentorial white matter, corpus callosum and left cerebellar peduncle (C). Bilateral hyperintensity in the temporal pole (O'Sullivan's sign).

Presented with these radiological findings, our differential diagnosis considered acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) due to the presence of pseudotumoural lesions in the left cerebellar peduncle. Although alterations in diffusion sequences and small-vessel vascular impairment led us to consider the possibility of vasculitis of the central nervous system, this was ruled out when no signs of stenosis were detected by the angioresonance. Given the presence of hyperintensity in the temporal pole (O'Sullivan's sign), we also considered the possibility of CADASIL. The rest of the studies that were carried out showed little of interest, enabling us to rule out any other infectious aetiologies (normal cerebrospinal fluid), demyelinating (negative oligoclonal bands) and cardioembolic (normal echocardiogram and cardiac monitoring). We were also able to rule out mitochondrial encephalopathy due to the absence of calcification in the Computed Tomography Scan of the Brain and the normal levels of lactic and pyruvic acid in the blood determination. Fabry's enzyme study also gave a negative result.

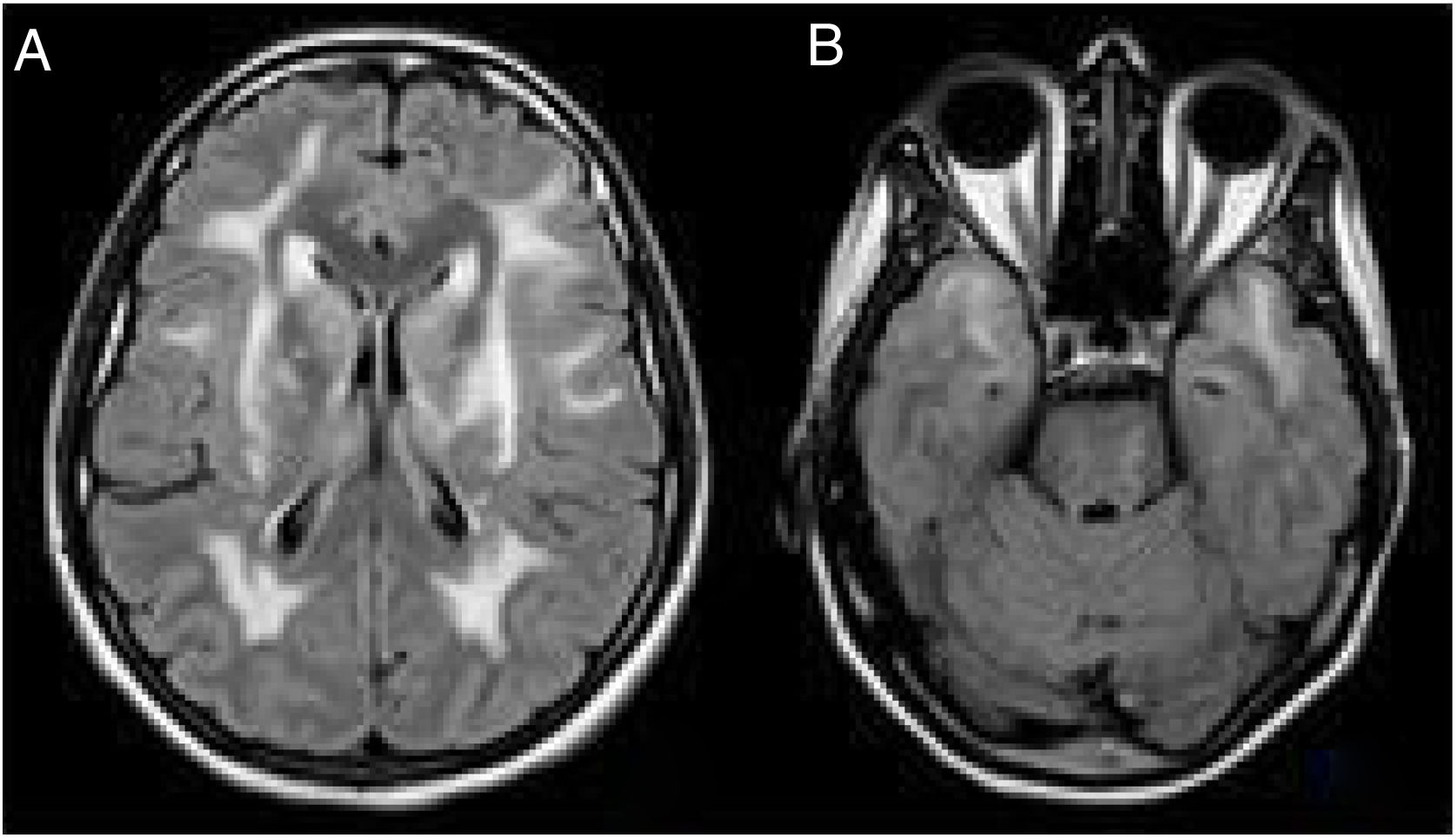

Despite the atypical form of the presentation, we reconsidered a diagnosis of CADASIL and reviewed the clinical history of the patient's father, who had presented ictal episodes associated with surgical interventions, progressive neurological deterioration and dementia. A cerebral MRI scan of the patient had also revealed extensive vascular affectation and signs of bilateral O'Sullivan's. A cerebral MRI scan of the patient's sister, who was asymptomatic other than suffering episodic cases of migraine with aura, produced a similar result (Fig. 2).

We requested a genetic NOTCH3 study, which produced negative results for mutations in exons 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 11. Finally, we carried out a clinical exome in which we detected a probable pathogenic heterozygous mutation c.1136G>A (p.C379Y) of the NOTCH3 gene; this was also present in the patient's sister.

At 12 months, the patient suffered a new acute stroke, with worsening ataxia, dysarthria and left dysmetria, within the context of contrast administration during fluorescein angiography. At the functional level, the patient need assistance with some daily activities (mRS 3); at the cognitive level, moderate fronto-subcortical cognitive impairment was evident, with a slowing of processing speed, attentional involvement in working memory and executive functions.

We present a case of CADASIL which had a hyperacute origin: with ischemic encephalopathy and multiple simultaneous acute infarcts revealed by an MRI scan. Acute encephalopathy is an uncommon manifestation of CADASIL, which is found in only 10% of cases.5 In a review of relevant bibliography, we found a case of CADASIL with an unusual debut which was revealed by MRI diagnosis. This occurred in the postoperative period, following a knee arthroplasty, and involved a missense heterozygous mutation c.1630C>T (p. Arg544Cys).6

At the pathophysiological level, it has been suggested that acute encephalopathy is preceded by recurrent migraine attacks or auras in the majority of cases. It has also been proposed that the cerebral vasoconstriction that tends to accompany incidences of migraine could precipitate attacks of encephalopathy.5,7 In our case, however, the acute encephalopathy that affected the patient occurred without any antecedents of migraine. This suggested that other factors that compromise cerebral circulation may also be associated with encephalopathy in CADASIL. We would particularly like to highlight the fact that, in the cases of both our patient and his father, the ictal episodes which had a neurological focus appeared within the context of surgery and/or the administration of general anesthesia. CADASIL is a disease which affects small blood vessels that threatens cerebral circulation and which can be exacerbated under certain specific circumstances, such as: dehydration, blood loss, anemia and cerebral vasoconstriction associated with surgery and general anesthetic.8 Recent studies have revealed a mechanism that exacerbates vulnerability to ischemic injury in CADASIL and which is linked to abnormal extracellular ion homeostasis and susceptibility to ischemic depolarization.9 It has been suggested that this condition may affect cerebral circulation, causing generalized hypoperfusion. This, in turn, could then cause multiple simultaneous acute lacunar infarcts and acute reversible encephalopathy. In cases of patients diagnosed with CADASIL who need to undergo surgery, it is therefore important to take perioperative precautions to prevent potential dehydration and anemia and, as far as possible, to avoid the administration of general anesthesia.10 Is also important to maintain normothermic and normocapnia conditions in order to prevent vasospastic phenomena and it is recommended to keep the patient's head elevated, and at an angle of 30°, in order to prevent the obstruction of cerebral venous drainage.10 In our case, we identified the NM_000435.2:c.1136G>A;NP_000426.2:p.C379Y variant of CADASIL. This involved a heterozygous change, which was detected in the NOTCH3 gene, consisting of a transition from a G to an A (c.1136G>A). At the protein level, this would presumably have resulted in the replacement of the cysteine at position 379 by a tyrosine (p.C379Y). In silico analysis, which was involved in the majority of the programs used, predicted that this was probably a deleterious change. At the same time, various other changes (c.1135T>G (p.C379G) (ID: 447776), c.1135T>C (p. C379R) (HM090054) and c.1136G>C (p.C379S) (ID:812744; CM052279) registered by the ClinVar and HGMD databases showed that the same amino acid, which is associated with the disease, was affected.

In the family segregation study, it was observed that the patient's sister presented the same mutation. This was revealed using a compatible MRI scan. However, the sister experienced a more benign affectation and has so far remained asymptomatic, with the exception of a few episodes of migraine with sporadic aura.

We have described a new mutation in the NOTCH3 gene which atypically manifests in the form of ischemic encephalopathy. Our experience with the patient discussed here highlights the importance of taking perioperative precautions in cases of CADASIL and, as far as possible, preventing the administration of general anesthesia and venous contrasts.

FundingThe authors declare no financial interest.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.