Information regarding hospital arrival times after acute ischaemic stroke (AIS) has mainly been gathered from countries with specialised stroke units. Little data from emerging nations are available. We aim to identify factors associated with achieving hospital arrival times of less than 1, 3, and 6 hours, and analyse how arrival times are related to functional outcomes after AIS.

MethodsWe analysed data from patients with AIS included in the PREMIER study (Primer Registro Mexicano de Isquemia Cerebral) which defined time from symptom onset to hospital arrival. The functional prognosis at 30 days and at 3, 6, and 12 months was evaluated using the modified Rankin Scale.

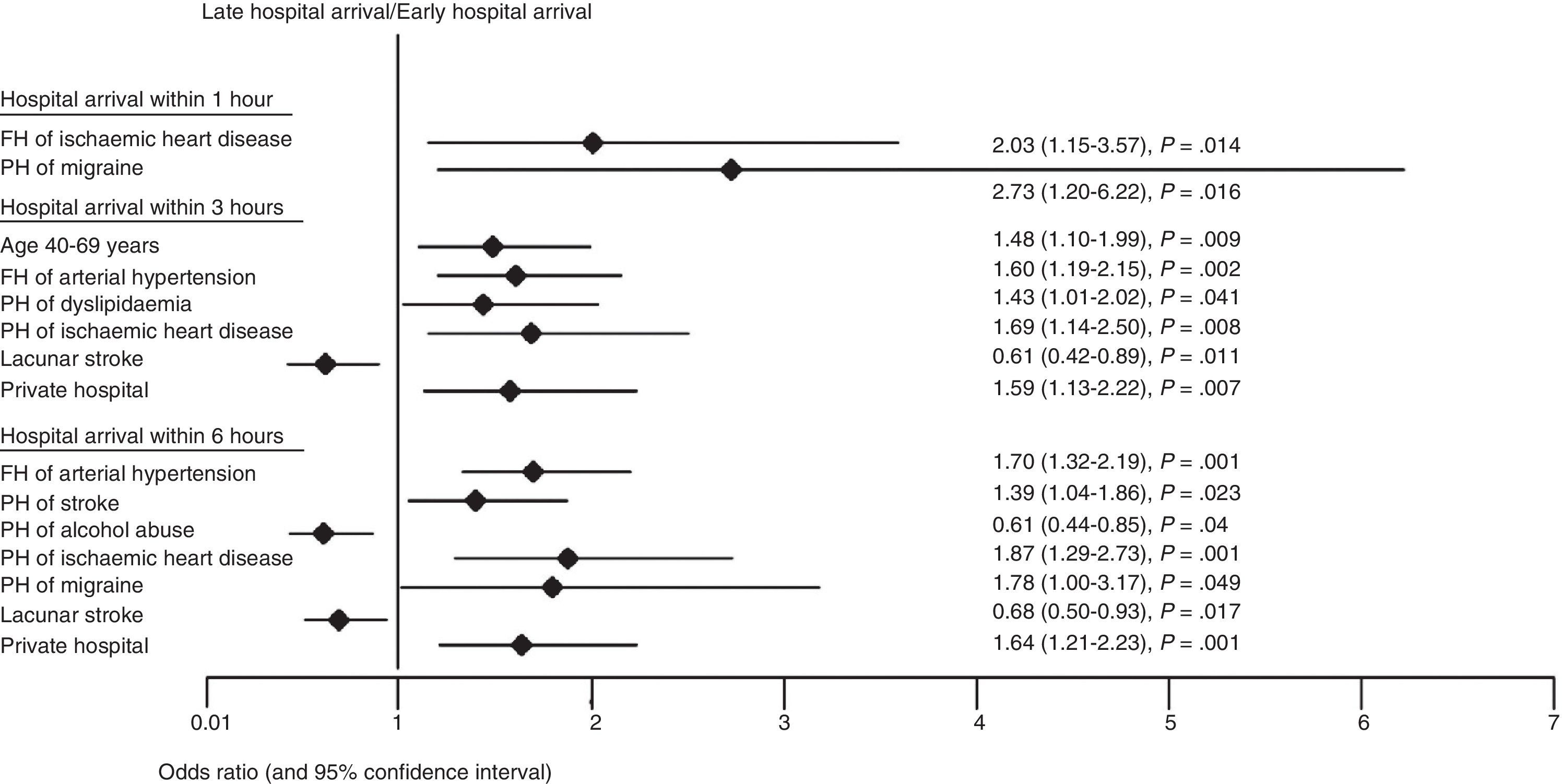

ResultsAmong 1096 patients with AIS, 61 (6%) arrived in <1 hour, 250 (23%) in <3 hours, and 464 (42%) in <6 hours. The factors associated with very early (<1h) arrival were family history of ischaemic heart disease and personal history of migraines; in <3 hours: age 40 to 69 years, family history of hypertension, personal history of dyslipidaemia and ischaemic heart disease, and care in a private hospital; in <6 hours: migraine, previous stroke, ischaemic heart disease, care in a private hospital, and family history of hypertension. Delayed hospital arrival was associated with lacunar stroke and alcoholism. Only 2.4% of patients underwent thrombolysis. Regardless of whether or not thrombolysis was performed, arrival time in <3 hours was associated with lower mortality at 3 and 6 months, and with fewer in-hospital complications.

ConclusionsA high percentage of patients had short hospital arrival times; however, less than 3% underwent thrombolysis. Although many factors were associated with early hospital arrival, it is a priority to identify in-hospital barriers to performing thrombolysis.

La información sobre el tiempo de llegada hospitalaria después de un infarto cerebral (IC) se ha originado en países con unidades especializadas en ictus. Existe poca información en naciones emergentes. Nos propusimos identificar los factores que influyen en el tiempo de llegada hospitalaria a 1, 3 y 6 h y su relación con el pronóstico funcional después del ictus.

MétodosSe analizó la información de pacientes con IC incluidos en el estudio Primer Registro Mexicano de Isquemia Cerebral (PREMIER) que tuvieran tiempo definido desde el inicio de los síntomas hasta la llegada hospitalaria. El desenlace funcional se evaluó mediante la escala modificada de Rankin a los 30 días, 3, 6 y 12 meses.

ResultadosDe 1.096 pacientes con IC, 61 (6%) llegaron en < 1 h, 250 (23%) en < 3 h y 464 (42%) en < 6 h. Favorecieron la llegada temprana en < 1 h: el antecedente familiar de cardiopatía isquémica y ser migrañoso; en < 3 h: edad 40-69 años, antecedente familiar de hipertensión, antecedente personal de dislipidemia y cardiopatía isquémica, así como la atención en hospital privado; en < 6 h: antecedente familiar de hipertensión, ser migrañoso, ictus previo, cardiopatía isquémica y atención en hospital privado. La llegada hospitalaria tardía se asoció a ictus lacunar y alcoholismo. Solo el 2,4% recibió trombólisis. Independientemente de la trombólisis, la llegada en < 3 h se asoció a menor mortalidad a los 3 y 6 meses, además de menos complicaciones intrahospitalarias.

ConclusionesUna proporción importante de pacientes tuvo un tiempo de llegada hospitalaria temprana; sin embargo, menos del 3% recibió trombólisis. Aunque muchos factores se asociaron a la llegada temprana, es prioritario identificar las barreras intrahospitalarias que obstaculizan la trombólisis.

For treatment of acute ischaemic stroke (AIS) to be effective, patients should reach the hospital within minutes of symptom onset, and both professionals and resources must be immediately available to achieve better short- and long-term prognoses.1,2 The introduction of new alternative therapies for ischaemic stroke, especially fibrinolytic therapy, requires patients to arrive promptly within the ‘therapeutic window’, a brief interval of less than 4.5 hours.3

Despite increased awareness regarding this basic requirement, only a few studies in local scientific literature mention hospital arrival times after an IS or the reasons for delay.4 Ischaemic heart disease is a condition that is quickly recognised as medical emergency by the general population and appropriately treated by medical professionals. In contrast, stroke signs and symptoms go undetected by the general population and are underdiagnosed by non-specialists. Some patients are referred to the wrong department and treated incorrectly at first.5,6

Our aim was to identify factors influencing early hospital arrival (1h, <3h and <6h) among patients with acute IS (not participating in clinical trials). To this end, we analysed outcomes from the first Mexican multicentre registry of ischaemic stroke (the PREMIER study).7

MethodsWe analysed data from the PREMIER study, which included consecutive patients with acute ischaemic stroke. These patients were admitted to different Mexican hospitals over a period of 2 years.7 The main aim of the PREMIER study was to assess conditions upon arrival, institutional management, and the patient's short-, medium- and long-term prognosis after IS or transient ischaemic attack. Neurologists and internists from secondary and tertiary hospitals in different Mexican regions participated in the study. The study included consecutive patients aged ≥18 years with neuroimaging-confirmed ischaemic stroke who received medical attention in a maximum of 7 days after the stroke. All participating researchers were able to classify the ischaemic stroke subtype according to the Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke and the Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project. Participants used the USA National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) to determine the severity of cerebrovascular disease and the modified Rankin Scale to measure the functional and neurological outcome. Patients were evaluated at discharge and at 30 days, as well as at 3, 6 and 12 months after being included. Hypertension, diabetes, past or current smoking habit, alcoholism, and sedentary lifestyle (less than 30minutes of physical exercise on fewer than 4 days a week) were measured using the corresponding international standards applicable for 2005. We excluded cases of transient ischaemic attack and patients whose time from symptom onset to hospital arrival was not recorded. Patients who suffered a stroke after having been hospitalised for a different disease were also excluded. We analysed hospital arrival times within 1 hour, 3 hours, and 6 hours of onset. The local Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee at each participating hospital approved the research protocol.

Statistical analysisDemographic data were presented along with measures of central tendency. We used the Pearson chi-square test (or the Fisher exact test where applicable) to compare the frequencies of nominal variables between two groups or to test for homogeneity of the distribution of variables in three or more groups. We used the t test to compare normally distributed continuous variables between two groups. To identify variables associated with hospital arrival times and mortality, we performed a multivariate analysis applying a binary logistic regression model. We considered the following to be independent predictors of early hospital arrival (less than 1, 3, and 6h): sociodemographic characteristics, heredity and family history, personal medical profile and history, access to public or private hospital, symptoms at stroke onset, severity according to NIHSS, and stroke subtype and mechanism. For the adjusted model, we selected variables associated with outcomes assessed when P<.1 in the exploratory univariate analysis. A risk assessment was carried out and expressed as odds ratio (OR) with a confidence interval of 95% (95% CI). Kaplan-Meier actuarial analyses were performed to provide survival estimates according to arrival time and the presence of in-hospital complications. We used the IBM statistical software package SPSS, version 20.0, for all calculations made during this study. The level of statistical significance was set at P<.05.

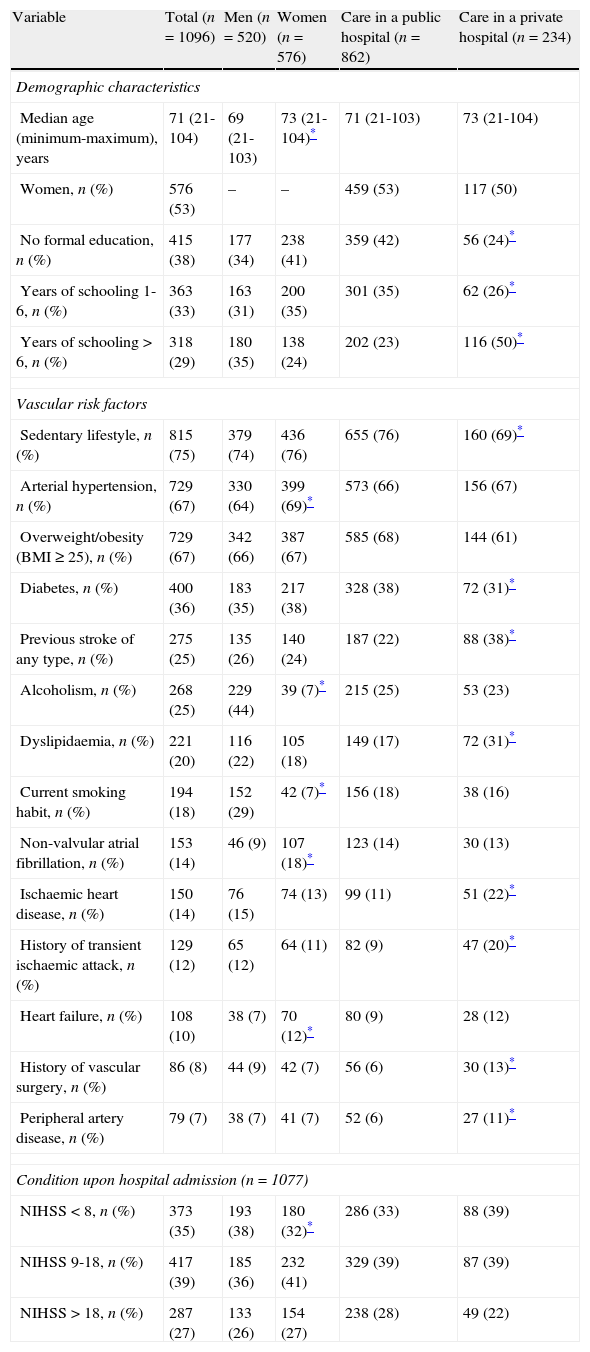

ResultsOf the 1376 patients in the PREMIER study's total cohort, we excluded 130 cases of transient ischaemic attack and 150 patients whose arrival time at hospital could not be determined. A total of 1096 patients were included in this study (Table 1), comprising 520 men (47%) and 576 women (53%), with a mean age of 68.4 years (limits, 21 to 104 years). A total of 63 (6%) were younger than 40 years and 597 (54%) were older than 70. The main risk factors were sedentary lifestyle (75%), hypertension (67%), overweight/obesity (67%), and diabetes (36%). Hypertension, non-valvular atrial fibrillation, and heart failure were significantly more frequent in women, while alcoholism and smoking were more frequent in men. Regarding hospital arrival times, 61 (6%) of patients arrived within 1 hour, 250 (23%) within the first 3 hours and 464 (42%) within the first 6 hours.

General characteristics of the study population (n=1096).

| Variable | Total (n=1096) | Men (n=520) | Women (n=576) | Care in a public hospital (n=862) | Care in a private hospital (n=234) |

| Demographic characteristics | |||||

| Median age (minimum-maximum), years | 71 (21-104) | 69 (21-103) | 73 (21-104)* | 71 (21-103) | 73 (21-104) |

| Women, n (%) | 576 (53) | – | – | 459 (53) | 117 (50) |

| No formal education, n (%) | 415 (38) | 177 (34) | 238 (41) | 359 (42) | 56 (24)* |

| Years of schooling 1-6, n (%) | 363 (33) | 163 (31) | 200 (35) | 301 (35) | 62 (26)* |

| Years of schooling >6, n (%) | 318 (29) | 180 (35) | 138 (24) | 202 (23) | 116 (50)* |

| Vascular risk factors | |||||

| Sedentary lifestyle, n (%) | 815 (75) | 379 (74) | 436 (76) | 655 (76) | 160 (69)* |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 729 (67) | 330 (64) | 399 (69)* | 573 (66) | 156 (67) |

| Overweight/obesity (BMI≥25), n (%) | 729 (67) | 342 (66) | 387 (67) | 585 (68) | 144 (61) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 400 (36) | 183 (35) | 217 (38) | 328 (38) | 72 (31)* |

| Previous stroke of any type, n (%) | 275 (25) | 135 (26) | 140 (24) | 187 (22) | 88 (38)* |

| Alcoholism, n (%) | 268 (25) | 229 (44) | 39 (7)* | 215 (25) | 53 (23) |

| Dyslipidaemia, n (%) | 221 (20) | 116 (22) | 105 (18) | 149 (17) | 72 (31)* |

| Current smoking habit, n (%) | 194 (18) | 152 (29) | 42 (7)* | 156 (18) | 38 (16) |

| Non-valvular atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 153 (14) | 46 (9) | 107 (18)* | 123 (14) | 30 (13) |

| Ischaemic heart disease, n (%) | 150 (14) | 76 (15) | 74 (13) | 99 (11) | 51 (22)* |

| History of transient ischaemic attack, n (%) | 129 (12) | 65 (12) | 64 (11) | 82 (9) | 47 (20)* |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 108 (10) | 38 (7) | 70 (12)* | 80 (9) | 28 (12) |

| History of vascular surgery, n (%) | 86 (8) | 44 (9) | 42 (7) | 56 (6) | 30 (13)* |

| Peripheral artery disease, n (%) | 79 (7) | 38 (7) | 41 (7) | 52 (6) | 27 (11)* |

| Condition upon hospital admission (n=1077) | |||||

| NIHSS <8, n (%) | 373 (35) | 193 (38) | 180 (32)* | 286 (33) | 88 (39) |

| NIHSS 9-18, n (%) | 417 (39) | 185 (36) | 232 (41) | 329 (39) | 87 (39) |

| NIHSS >18, n (%) | 287 (27) | 133 (26) | 154 (27) | 238 (28) | 49 (22) |

CBD: cerebrovascular disease; BMI: body mass index; NIHSS: National Institute of Health Stroke Scale.

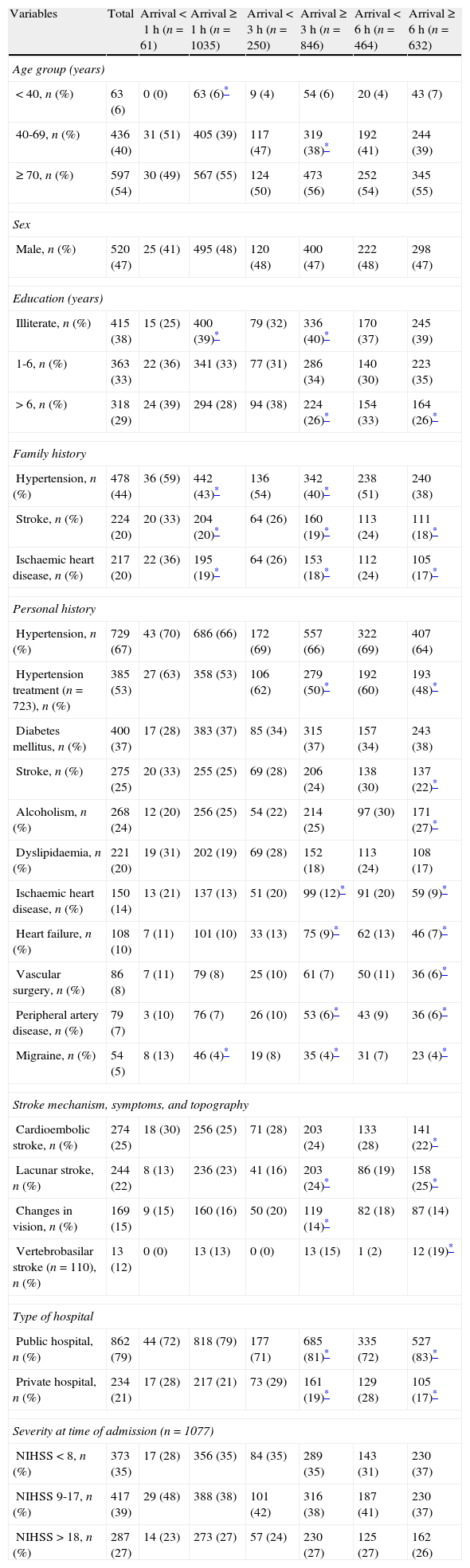

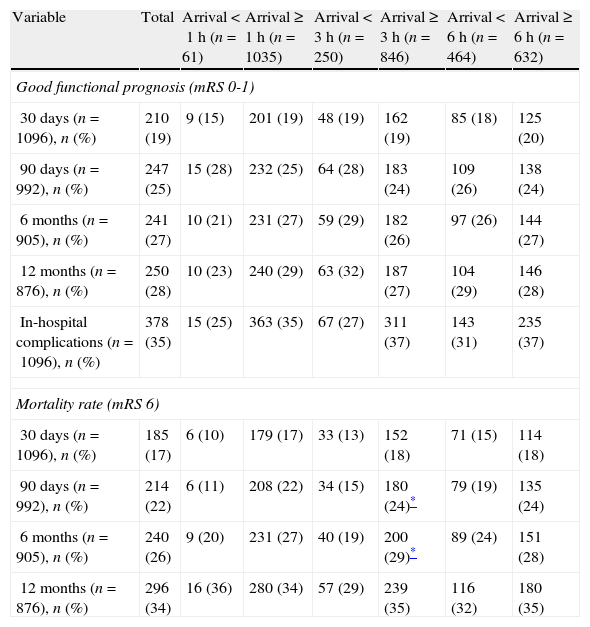

According to the univariate analysis, factors favouring hospital arrival within 1 hour were as follows: family history of hypertension, stroke, and ischaemic heart disease, and personal history of dyslipidaemia and migraines. Being younger than 40 years and illiterate were factors with an adverse effect on the probability of a hospital arrival within 1 hour (Table 2). In the multivariate analysis, family history of ischaemic heart disease and personal history of migraine favoured prompt arrival within 1 hour (Fig. 1).

Univariate analysis of factors affecting hospital arrival time after ischaemic stroke, broken down by arrival interval (n=1096).

| Variables | Total | Arrival <1h (n=61) | Arrival ≥1h (n=1035) | Arrival <3h (n=250) | Arrival ≥3h (n=846) | Arrival <6h (n=464) | Arrival ≥6h (n=632) |

| Age group (years) | |||||||

| <40, n (%) | 63 (6) | 0 (0) | 63 (6)* | 9 (4) | 54 (6) | 20 (4) | 43 (7) |

| 40-69, n (%) | 436 (40) | 31 (51) | 405 (39) | 117 (47) | 319 (38)* | 192 (41) | 244 (39) |

| ≥70, n (%) | 597 (54) | 30 (49) | 567 (55) | 124 (50) | 473 (56) | 252 (54) | 345 (55) |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male, n (%) | 520 (47) | 25 (41) | 495 (48) | 120 (48) | 400 (47) | 222 (48) | 298 (47) |

| Education (years) | |||||||

| Illiterate, n (%) | 415 (38) | 15 (25) | 400 (39)* | 79 (32) | 336 (40)* | 170 (37) | 245 (39) |

| 1-6, n (%) | 363 (33) | 22 (36) | 341 (33) | 77 (31) | 286 (34) | 140 (30) | 223 (35) |

| >6, n (%) | 318 (29) | 24 (39) | 294 (28) | 94 (38) | 224 (26)* | 154 (33) | 164 (26)* |

| Family history | |||||||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 478 (44) | 36 (59) | 442 (43)* | 136 (54) | 342 (40)* | 238 (51) | 240 (38) |

| Stroke, n (%) | 224 (20) | 20 (33) | 204 (20)* | 64 (26) | 160 (19)* | 113 (24) | 111 (18)* |

| Ischaemic heart disease, n (%) | 217 (20) | 22 (36) | 195 (19)* | 64 (26) | 153 (18)* | 112 (24) | 105 (17)* |

| Personal history | |||||||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 729 (67) | 43 (70) | 686 (66) | 172 (69) | 557 (66) | 322 (69) | 407 (64) |

| Hypertension treatment (n=723), n (%) | 385 (53) | 27 (63) | 358 (53) | 106 (62) | 279 (50)* | 192 (60) | 193 (48)* |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 400 (37) | 17 (28) | 383 (37) | 85 (34) | 315 (37) | 157 (34) | 243 (38) |

| Stroke, n (%) | 275 (25) | 20 (33) | 255 (25) | 69 (28) | 206 (24) | 138 (30) | 137 (22)* |

| Alcoholism, n (%) | 268 (24) | 12 (20) | 256 (25) | 54 (22) | 214 (25) | 97 (30) | 171 (27)* |

| Dyslipidaemia, n (%) | 221 (20) | 19 (31) | 202 (19) | 69 (28) | 152 (18) | 113 (24) | 108 (17) |

| Ischaemic heart disease, n (%) | 150 (14) | 13 (21) | 137 (13) | 51 (20) | 99 (12)* | 91 (20) | 59 (9)* |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 108 (10) | 7 (11) | 101 (10) | 33 (13) | 75 (9)* | 62 (13) | 46 (7)* |

| Vascular surgery, n (%) | 86 (8) | 7 (11) | 79 (8) | 25 (10) | 61 (7) | 50 (11) | 36 (6)* |

| Peripheral artery disease, n (%) | 79 (7) | 3 (10) | 76 (7) | 26 (10) | 53 (6)* | 43 (9) | 36 (6)* |

| Migraine, n (%) | 54 (5) | 8 (13) | 46 (4)* | 19 (8) | 35 (4)* | 31 (7) | 23 (4)* |

| Stroke mechanism, symptoms, and topography | |||||||

| Cardioembolic stroke, n (%) | 274 (25) | 18 (30) | 256 (25) | 71 (28) | 203 (24) | 133 (28) | 141 (22)* |

| Lacunar stroke, n (%) | 244 (22) | 8 (13) | 236 (23) | 41 (16) | 203 (24)* | 86 (19) | 158 (25)* |

| Changes in vision, n (%) | 169 (15) | 9 (15) | 160 (16) | 50 (20) | 119 (14)* | 82 (18) | 87 (14) |

| Vertebrobasilar stroke (n=110), n (%) | 13 (12) | 0 (0) | 13 (13) | 0 (0) | 13 (15) | 1 (2) | 12 (19)* |

| Type of hospital | |||||||

| Public hospital, n (%) | 862 (79) | 44 (72) | 818 (79) | 177 (71) | 685 (81)* | 335 (72) | 527 (83)* |

| Private hospital, n (%) | 234 (21) | 17 (28) | 217 (21) | 73 (29) | 161 (19)* | 129 (28) | 105 (17)* |

| Severity at time of admission (n=1077) | |||||||

| NIHSS <8, n (%) | 373 (35) | 17 (28) | 356 (35) | 84 (35) | 289 (35) | 143 (31) | 230 (37) |

| NIHSS 9-17, n (%) | 417 (39) | 29 (48) | 388 (38) | 101 (42) | 316 (38) | 187 (41) | 230 (37) |

| NIHSS >18, n (%) | 287 (27) | 14 (23) | 273 (27) | 57 (24) | 230 (27) | 125 (27) | 162 (26) |

NIHSS: National Institute of Health Stroke Scale.

Factors favouring arrival within 3 hours of onset were age between 40 and 69 years; years of schooling >6; family history of hypertension, stroke, and ischaemic heart disease; and personal history of treated arterial hypertension, dyslipidaemia, ischaemic heart disease, heart failure, peripheral artery disease, and migraine. Visual symptoms at stroke onset and seeking care in a private hospital also favoured arrival within 3 hours. The situations leading to later hospital arrival times in the first 3-hour interval were being illiterate, seeking care in a public hospital, and presenting small-vessel disease (lacunar stroke) (Table 2). In the multivariate analysis, factors contributing to hospital arrival within 3 hours were age between 40 and 69 years, family history of hypertension, personal history of dyslipidaemia, having ischaemic heart disease, and seeking care in a private hospital. We also determined that lacunar stroke was a factor associated with hospital arrival times in excess of 3 hours (Fig. 1). Since clinical manifestations of lacunar stroke are variable, and given that a ‘strategic’ lesion is one that gives rise to a pure motor deficit (which translates into greater physical disability), we analysed hospital arrival times according to stroke severity in a subgroup of patients with lacunar stroke (n=238). We observed no significant differences in the percentage of cases with arrival times of less than 3 hours between patients with an NIHSS score <5 points and those scoring ≥5 (15% vs 20%, respectively; P=.52). Results were similar for patients scoring <10 or ≥10 on the NIHSS (19% vs 18%, respectively; P=.52).

Arrival time within 6 hoursThe following factors promoted hospital arrival within 6 hours: more than 6 years of schooling, family history of hypertension, stroke and ischaemic heart disease, personal history of hypertension treatment, prior history of stroke, alcoholism, dyslipidaemia, ischaemic heart disease, heart failure, history of vascular surgery, peripheral artery disease, migraine, cardioembolic stroke and care in a private hospital. Later hospital arrival times in the first 6-hour interval were associated with care in a public hospital, lacunar stroke, and stroke in the vertebrobasilar territory (Table 2). Multivariate analysis showed the following factors to be associated with arrival within 6 hours: family history of hypertension, personal history of stroke, ischaemic heart disease and migraine, and seeking care in a private hospital. In this analysis, alcoholism and lacunar stroke were associated with hospital arrival times exceeding 6 hours (Fig. 1). Stroke severity did not affect hospital arrival time in any of the 3 time intervals in the analysis (Table 2).

Hospital arrival and reperfusion therapyThe PREMIER study was carried out between 2004 and 2006. At that time, the therapeutic window for intravenous fibrinolysis was 3 hours.8 Of the total of 1096 patients studied, 4 (6.5%) of the 61 patients arriving in the first hour underwent fibrinolysis. Among patients arriving between the first and the third hour (n=189), 14 (7.4%) underwent thrombolysis. Among patients arriving between the third and the sixth hour (n=214), 9 (4.2%) were treated with intra-arterial thrombolysis.

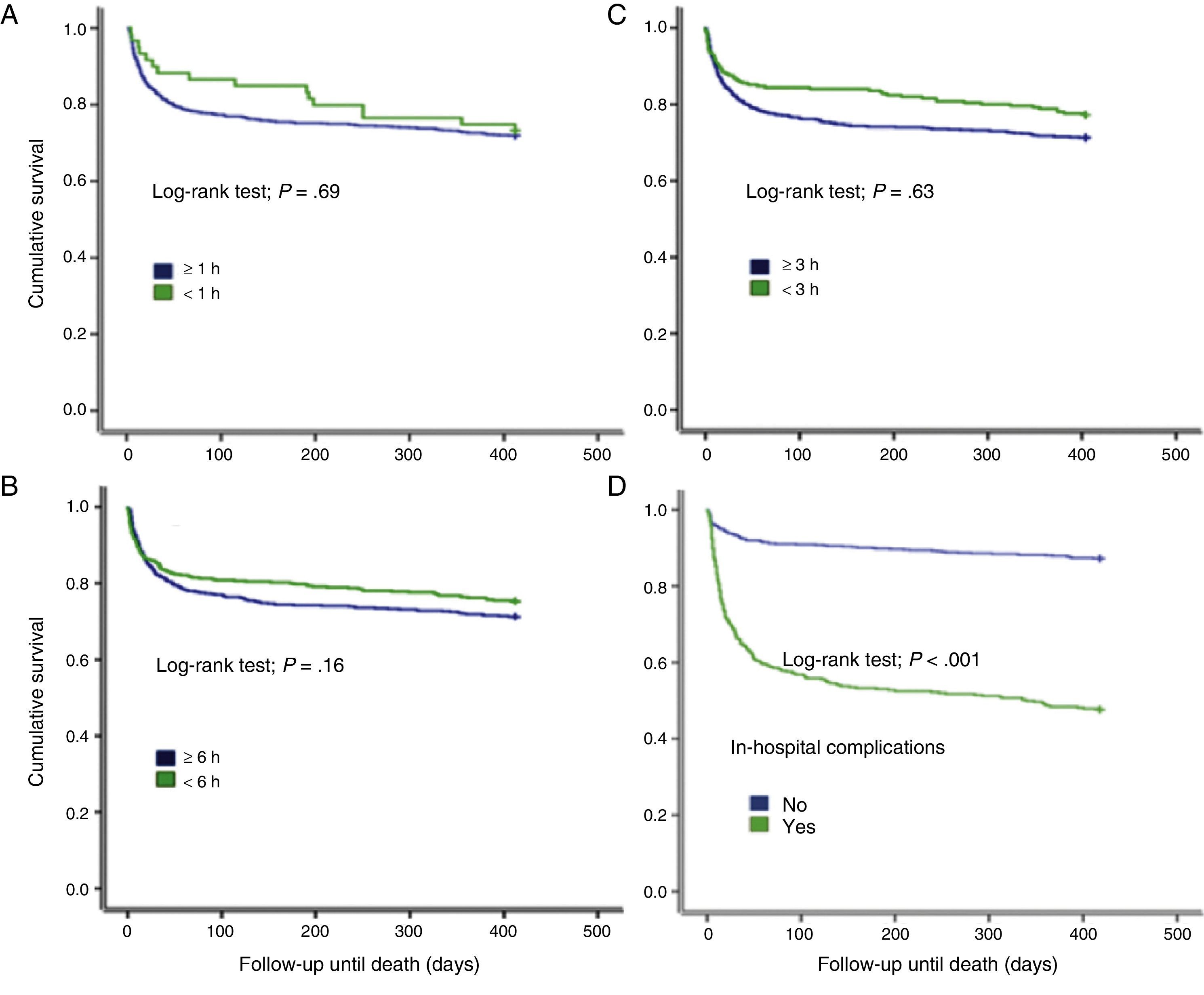

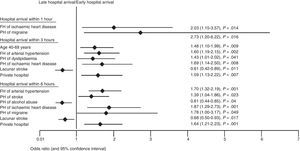

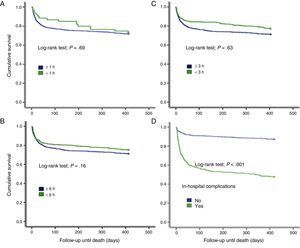

Arrival time, in-hospital complications, and prognosisHospital arrival time (within 3 or 6h of onset) was associated with a lower rate of in-hospital complications and lower 3-month and 6-month mortality rates (P<.05) (Table 3). According to the Kaplan-Meier actuarial survival analysis, arrival time did not have an impact on 12-month mortality. However, we observed a tendency towards a lower 3-month mortality rate, as well as lower mortality among patients with no in-hospital complications (Fig. 2). Age>80 years (n=264, 24.1%) was neither directly nor indirectly associated with hospital arrival time in the univariate or multivariate analysis. A positive association was only found for patients aged 40 to 69 (Table 2).

Univariate analysis for functional outcome and complications/death in the short- and medium-term following a cerebral infarct, broken down by hospital arrival time.

| Variable | Total | Arrival <1h (n=61) | Arrival ≥1h (n=1035) | Arrival <3h (n=250) | Arrival ≥3h (n=846) | Arrival <6h (n=464) | Arrival ≥6h (n=632) |

| Good functional prognosis (mRS 0-1) | |||||||

| 30 days (n=1096), n (%) | 210 (19) | 9 (15) | 201 (19) | 48 (19) | 162 (19) | 85 (18) | 125 (20) |

| 90 days (n=992), n (%) | 247 (25) | 15 (28) | 232 (25) | 64 (28) | 183 (24) | 109 (26) | 138 (24) |

| 6 months (n=905), n (%) | 241 (27) | 10 (21) | 231 (27) | 59 (29) | 182 (26) | 97 (26) | 144 (27) |

| 12 months (n=876), n (%) | 250 (28) | 10 (23) | 240 (29) | 63 (32) | 187 (27) | 104 (29) | 146 (28) |

| In-hospital complications (n=1096), n (%) | 378 (35) | 15 (25) | 363 (35) | 67 (27) | 311 (37) | 143 (31) | 235 (37) |

| Mortality rate (mRS 6) | |||||||

| 30 days (n=1096), n (%) | 185 (17) | 6 (10) | 179 (17) | 33 (13) | 152 (18) | 71 (15) | 114 (18) |

| 90 days (n=992), n (%) | 214 (22) | 6 (11) | 208 (22) | 34 (15) | 180 (24)* | 79 (19) | 135 (24) |

| 6 months (n=905), n (%) | 240 (26) | 9 (20) | 231 (27) | 40 (19) | 200 (29)* | 89 (24) | 151 (28) |

| 12 months (n=876), n (%) | 296 (34) | 16 (36) | 280 (34) | 57 (29) | 239 (35) | 116 (32) | 180 (35) |

mRS: modified Rankin Scale.

Factors affecting hospital arrival times in cases of stroke were studied even before rt-PA was approved as the standard of care for reperfusion in acute IS.9–11 These studies have mainly been carried out in developed countries with more effective referral and prehospital management practices for stroke patients.12–14 Much of the data have been generated within the context of well-defined prehospital management protocols or during the course of pharmacological research. This may significantly bias the outcomes.12–16 At the same time, these studies were conducted with different populations, designs, and objectives, resulting in very different conclusions.15–20 Few studies have examined this aspect of stroke in Latin American countries, and fewer still in Mexico.4,21

In line with conclusions from other studies,4,22 we observed here that women were older than men and had a somewhat different distribution of vascular risk factors. In women, hypertension, atrial fibrillation, and heart failure were more frequent while the prevalence of smoking and alcoholism was lower. Furthermore, we observed a higher rate of cardioembolic stroke in women, which partly explains why they also show a different distribution of stroke severity according to the NIHSS. Even so, prognosis and hospital stay did not differ significantly between the two sexes. It is relevant that our findings are very similar to those published by Arboix et al. in 2001 from a large Spanish cohort.22 Using the registry, we analysed factors promoting or delaying the patient's hospital arrival within 1 hour, 3 hours, or 6 hours after onset of stroke symptoms. Analysis of arrival times within 6 hours, but outside the 4.5-hour therapeutic window currently recommended for intravenous thrombolysis,3 is based on evidence of positive outcomes achieved with alternative reperfusion therapies such as intra-arterial or combined thrombolysis or the use of mechanical thrombectomy devices.23,24 The analysis is also based on recent evidence on the potential benefit of intravenous rt-PA in the first 6 hours after stroke25 and the use of new thrombolytic drugs supported by perfusion- and diffusion-weighted imaging techniques.25–27 An important limitation of our study is its lack of an analysis that contemplates the current 4.5-hour cut-off point for delivering intravenous thrombolysis. The explanation for this absence is that extending the therapeutic window for intravenous thrombolysis (from 3.0 to 4.5h) was beginning to be discussed when the PREMIER study was already in an advanced stage.3

Factors associated with earlier hospital arrival were family history of cardiovascular disease, personal history of dyslipidaemia and migraine, and seeking care in a private hospital. Conditions associated with later arrival times were lacunar stroke and personal history of alcoholism. Living with relatives with cardiovascular disease raises awareness among family members and helps them make immediate decisions when faced with similar situations.6,14 However, personal history of dyslipidaemia and migraine had never before been identified as factors contributing to an early hospital arrival. It should be stressed that personal history of those two factors was more significant than a history of diabetes or hypertension. This may have to do with cultural factors specific to the Mexican population. Further studies will be necessary to confirm these findings. With regard to education, we can probably say that the higher educational levels ensure greater access to information on vascular risk factors, better detection of stroke symptoms, and better decision-making in terms of referral and management. All of the above could contribute to early hospital arrival.17,28 However, in our study, multivariate analysis did not identify educational level as a determinant of hospital arrival time. On the other hand, access to a private hospital was associated with early arrival. It is probable that purchasing power is the condition underlying this association, regardless of the patient's educational level. Additional studies will be needed to evaluate these findings. Lacunar stroke and events in the vertebrobasilar territory were associated with later arrival times, which coincides with results published by other authors.29,30 The most plausible explanation resides in the less severe symptoms usually present in lacunar stroke and the non-specific symptoms seen in vertebrobasilar stroke. One limitation of our study was that no clinical descriptions were given of lacunar strokes. Access to this information would have allowed us to determine whether patients with the dense motor deficits typical of pure motor hemiparesis have shorter arrival times than others.

Interestingly and surprisingly, personal history of stroke was not associated with a hospital arrival time of less than 3 hours. On this topic, researchers have discussed whether cognitive, affective, and language sequelae might limit patients experiencing a new stroke.14 We do not rule out that patients and carers in our setting can lose sight of the ‘urgent’ nature of a new stroke due to previous negative experiences related to stroke care and events following a stroke. In our study, stroke severity according to the NIHSS score did not affect early hospital arrival, contrary to results from other studies.2 This might also indicate that the Mexican population has a fatalistic attitude regarding prognosis for cerebrovascular disease.

One of the most noteworthy findings from the registry is the significant number of patients reaching hospital within 3 hours of onset (a quarter of the total) and within 6 hours (almost half of the study population). This reveals potential for improvement in the field of IS reperfusion therapy in our setting. However, there was an alarmingly low rate of thrombolysis (less than 3% of the patient total and 7.2% of patients arriving within the first 3 hours) during the data collection period, which was before the rt-PA therapeutic window had been extended to 4.5 hours. This fact requires us to take a closer look at the circumstances preventing fibrinolytic treatment. They have been studied in other scenarios31 in which patients were even treated on-site thanks to mobile stroke units.32,33 Another limitation of this scientific study is its lack of analysis of the therapeutic options available in the different participating hospitals. This arose because the original design of the PREMIER study did not contemplate investigating in-hospital factors associated with use of thrombolysis or other therapeutic strategies, including intra-arterial intervention and decompressive craniectomy.

Our study also shows that, regardless of whether thrombolysis is delivered, prompt hospital arrival is associated with good functional prognosis. This finding coincides with results from other scientific studies.4,34–36

In conclusion, lowering the hospital arrival times to within the reperfusion window (for any type of reperfusion therapy) is unquestionably a key goal for our setting. However, we also need to identify the in-hospital obstacles that prevent delivery of these treatment options to patients. The impact of a prompt hospital arrival after an IS translates into lower complication rates and reduced mortality rates over the short and medium term.

FundingThe PREMIER study received unrestricted financial support from SANOFI, from design to completion.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The authors would like to thank SANOFI Mexico, the PREMIER researchers, and patients and their families for their support.

Please cite this article as: León-Jiménez C, Ruiz-Sandoval JL, Chiquete E, Vega-Arroyo M, Arauz A, Murillo-Bonilla LM, et al. Tiempo de llegada hospitalaria y pronóstico funcional después de un infarto cerebral: resultados del estudio PREMIER. Neurología. 2014;29:200–209.