In the field of headaches, onabotulinumtoxinA (onabotA) is well established as a treatment for chronic migraine (CM). In recent years, it has been used increasingly to treat other primary headaches (high-frequency episodic migraine, trigeminal-autonomic cephalalgias, nummular headache) and trigeminal neuralgia. As this treatment will progressively be incorporated in the management of these patients, we consider it necessary to reflect, with a fundamentally practical approach, on the possible indications of onabotA, beyond CM, as well as its administration protocol, which will differ according to the type of headache and/or neuralgia.

DevelopmentThis consensus document was drafted based on a thorough review and analysis of the existing literature and our own clinical experience. The aim of the document is to serve as guidelines for professionals administering onabotA treatment. The first part will address onabotA’s mechanism of action, and reasons for its use in other types of headache, from a physiopathological and clinical perspective. In the second part, we will review the available evidence and studies published in recent years. We will add an “expert recommendation” based on our own clinical experience, showing the best patient profile for this treatment and the most adequate dose and administration protocol.

ConclusionTreatment with onabotA should always be individualised and considered in selected patients who have not responded to conventional therapy.

En el campo de las cefaleas, OnabotulinumtoxinA (OnabotA) tiene indicación bien establecida en la migraña crónica (MC). Además, en los últimos años su uso se está extendiendo a otras cefaleas primarias (migraña episódica de alta frecuencia, cefaleas trigémino-autonómicas, cefalea numular) y a la neuralgia del trigémino. Al ser una opción terapéutica que se va a ir incorporando de forma progresiva en el manejo de estas entidades, creemos que es necesario reflejar con un carácter eminentemente práctico cuáles son las posibles indicaciones de OnabotA, más allá de la MC, así como su protocolo de administración, que diferirá en función del tipo de cefalea y/o neuralgia.

DesarrolloA partir de una revisión de la bibliografía existente y de nuestra propia experiencia clínica, se ha elaborado este documento de consenso cuyo objetivo es servir de guía a aquellos profesionales que quieran aplicar estas técnicas en su actividad asistencial. En la primera parte se abordará el mecanismo de acción de OnabotA y la razón de su utilización en diversas cefaleas distintas de la MC desde un punto de vista fisiopatológico y clínico. En la segunda parte se hará una revisión de la evidencia disponible y los estudios publicados en los últimos años. Para cada una de estas entidades, se añadirá una “recomendación de experto”, basada en la propia experiencia clínica, que refleje el perfil de paciente que puede ser candidato a este tratamiento, las dosis y el protocolo de administración de OnabotA.

ConclusiónEl tratamiento con OnabotA en entidades distintas a la MC debe ser siempre individualizado y se planteará en pacientes seleccionados que no hayan respondido a la terapia convencional.

One of the objectives of the Spanish Society of Neurology’s Headache Study Group (GECSEN) is to issue consensus statements to establish good practice guidelines based on experience and evidence. In Spain, onabotulinumtoxinA (onabotA) was approved in 2012 as a preventive treatment for chronic migraine in patients showing poor response or intolerance to preventive oral drug therapy. GECSEN’s 2015 Official Clinical Practice Guidelines for Headache,1 published after the Phase III Research Evaluating Migraine Prophylaxis Therapy (PREEMPT) studies,2,3 recommend onabotA treatment in patients presenting intolerance, contraindication, or lack of response to at least 2 preventive drugs (topiramate and one beta-blocker) administered at the minimum recommended dose for at least 3 months (level of evidence IV, grade of recommendation: GECSEN).

In recent years, the use of onabotA has been extended to primary headaches other than chronic migraine (high-frequency episodic migraine [HFEM], trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias [TAC], nummular headache, and trigeminal neuralgia). As the use of onabotA for managing these primary headaches is expected to increase progressively, we consider it necessary to publish practical guidelines describing all possible indications of the drug and its administration protocol according to the type of headache and/or neuralgia.

This consensus document is based on the results of a thorough literature review and on our own clinical experience, and aims to provide a set of guidelines for the use of onabotA in patients with primary headaches other than chronic migraine.

MethodsThis consensus document was created by a group of neurologists specialising in the management of patients with headache. We selected primary headaches and neuralgias included in the International Classification of Headache Disorders, third edition, beta version (ICHD-3 Beta),4 that may benefit from treatment with onabotA, describe the pathophysiological basis supporting use of the drug, and establish an administration protocol based on our experience and the available evidence.

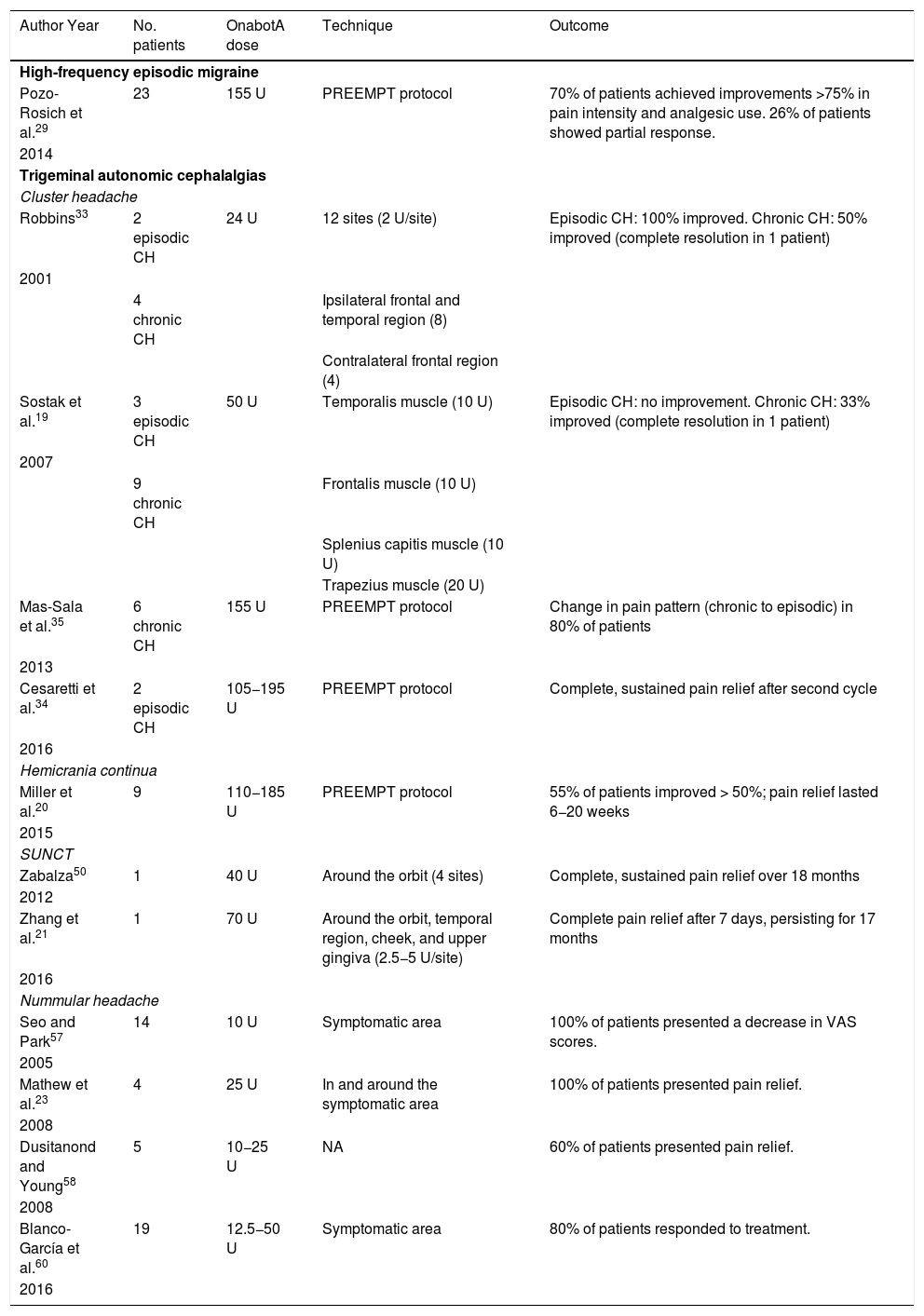

The first part of the document describes the action mechanism of onabotA and the pathophysiological and clinical reasons for its use to manage other headaches. The second part reviews the available evidence on the use of onabotA for HFEM, TAC, nummular headache, and trigeminal neuralgia. For each entity, we provide expert recommendations on the ideal patient profile, dose, and administration protocol for onabotA treatment, based on our clinical experience. Tables 1 and 2 summarise the main studies into the use of onabotA to treat different primary headaches and trigeminal neuralgia.

The main clinical trials of onabotulinumtoxinA for different drug-resistant primary headaches.

| Author Year | No. patients | OnabotA dose | Technique | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-frequency episodic migraine | ||||

| Pozo-Rosich et al.29 | 23 | 155 U | PREEMPT protocol | 70% of patients achieved improvements >75% in pain intensity and analgesic use. 26% of patients showed partial response. |

| 2014 | ||||

| Trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias | ||||

| Cluster headache | ||||

| Robbins33 | 2 episodic CH | 24 U | 12 sites (2 U/site) | Episodic CH: 100% improved. Chronic CH: 50% improved (complete resolution in 1 patient) |

| 2001 | ||||

| 4 chronic CH | Ipsilateral frontal and temporal region (8) | |||

| Contralateral frontal region (4) | ||||

| Sostak et al.19 | 3 episodic CH | 50 U | Temporalis muscle (10 U) | Episodic CH: no improvement. Chronic CH: 33% improved (complete resolution in 1 patient) |

| 2007 | ||||

| 9 chronic CH | Frontalis muscle (10 U) | |||

| Splenius capitis muscle (10 U) | ||||

| Trapezius muscle (20 U) | ||||

| Mas-Sala et al.35 | 6 chronic CH | 155 U | PREEMPT protocol | Change in pain pattern (chronic to episodic) in 80% of patients |

| 2013 | ||||

| Cesaretti et al.34 | 2 episodic CH | 105−195 U | PREEMPT protocol | Complete, sustained pain relief after second cycle |

| 2016 | ||||

| Hemicrania continua | ||||

| Miller et al.20 | 9 | 110−185 U | PREEMPT protocol | 55% of patients improved > 50%; pain relief lasted 6−20 weeks |

| 2015 | ||||

| SUNCT | ||||

| Zabalza50 | 1 | 40 U | Around the orbit (4 sites) | Complete, sustained pain relief over 18 months |

| 2012 | ||||

| Zhang et al.21 | 1 | 70 U | Around the orbit, temporal region, cheek, and upper gingiva (2.5−5 U/site) | Complete pain relief after 7 days, persisting for 17 months |

| 2016 | ||||

| Nummular headache | ||||

| Seo and Park57 | 14 | 10 U | Symptomatic area | 100% of patients presented a decrease in VAS scores. |

| 2005 | ||||

| Mathew et al.23 | 4 | 25 U | In and around the symptomatic area | 100% of patients presented pain relief. |

| 2008 | ||||

| Dusitanond and Young58 | 5 | 10−25 U | NA | 60% of patients presented pain relief. |

| 2008 | ||||

| Blanco-García et al.60 | 19 | 12.5−50 U | Symptomatic area | 80% of patients responded to treatment. |

| 2016 | ||||

CH: cluster headache; NA: not available; onabotA: onabotulinumtoxinA; PREEMPT: Phase III Research Evaluating Migraine Prophylaxis Therapy study; SUNCT: short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attack with conjunctival injection and tearing; U: unit; VAS: visual analogue scale.

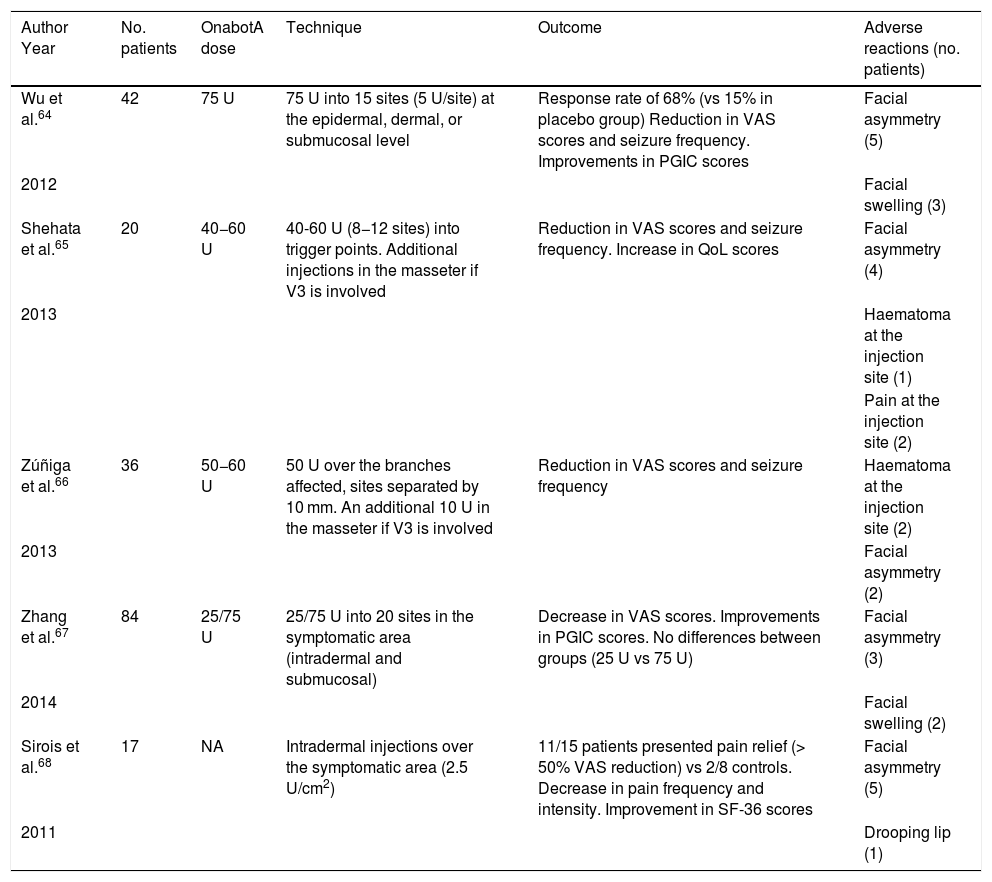

Randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials of onabotulinumtoxinA in patients with trigeminal neuralgia.

| Author Year | No. patients | OnabotA dose | Technique | Outcome | Adverse reactions (no. patients) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wu et al.64 | 42 | 75 U | 75 U into 15 sites (5 U/site) at the epidermal, dermal, or submucosal level | Response rate of 68% (vs 15% in placebo group) Reduction in VAS scores and seizure frequency. Improvements in PGIC scores | Facial asymmetry (5) |

| 2012 | Facial swelling (3) | ||||

| Shehata et al.65 | 20 | 40−60 U | 40-60 U (8−12 sites) into trigger points. Additional injections in the masseter if V3 is involved | Reduction in VAS scores and seizure frequency. Increase in QoL scores | Facial asymmetry (4) |

| 2013 | Haematoma at the injection site (1) | ||||

| Pain at the injection site (2) | |||||

| Zúñiga et al.66 | 36 | 50−60 U | 50 U over the branches affected, sites separated by 10 mm. An additional 10 U in the masseter if V3 is involved | Reduction in VAS scores and seizure frequency | Haematoma at the injection site (2) |

| 2013 | Facial asymmetry (2) | ||||

| Zhang et al.67 | 84 | 25/75 U | 25/75 U into 20 sites in the symptomatic area (intradermal and submucosal) | Decrease in VAS scores. Improvements in PGIC scores. No differences between groups (25 U vs 75 U) | Facial asymmetry (3) |

| 2014 | Facial swelling (2) | ||||

| Sirois et al.68 | 17 | NA | Intradermal injections over the symptomatic area (2.5 U/cm2) | 11/15 patients presented pain relief (> 50% VAS reduction) vs 2/8 controls. Decrease in pain frequency and intensity. Improvement in SF-36 scores | Facial asymmetry (5) |

| 2011 | Drooping lip (1) |

NA: not available; onabotA: onabotulinumtoxinA; PGIC: Patient Global Impression of Change scale; QoL: 10-point Quality of Life scale; SF-36: 36-Item Short Form Health Survey; U: unit; VAS: visual analogue scale.

Although the action mechanism of onabotA on pain is not fully understood, it is widely accepted that the drug blocks the release of calcitonin gene–related peptide (CGRP), glutamate, and other algogenic neuropeptides and neurotransmitters from neurons in the trigeminovascular system.5 Furthermore, onabotA inhibits the expression of some ion channels (transient receptor potential vanilloid subtype 1, P2 × 3 purinergic receptor) in trigeminovascular system neurons that regulate response to mechanical6 and chemical nociceptive stimuli.7 This modulation of trigeminal neurons (first-order neurons) inhibits not only peripheral but also central sensitisation; this mechanism is involved in the chronification of craniofacial pain. Given that most types of chronic craniofacial pain involve central and peripheral sensitisation, the use of onabotA for entities other than chronic migraine may be justified from a pathophysiological viewpoint.

OnabotA may have an indirect effect on the central nervous system, modulating the release of such excitatory neurotransmitters as glutamate and the activity of the endogenous opioid system, reducing the perception of pain.8,9 In fact, fragments of protein SNAP-25 have been detected in satellite glial cells in the trigeminal ganglion. Therefore, onabotA acts not only on peripheral neurons but also on glial cells in the trigeminal ganglion, inhibiting glutamate release at this level.10,11

High-frequency episodic migraineBased on the hypothesis that the pathophysiology of HFEM is not significantly different from that of chronic migraine, the use of onabotA may be justified in these patients during the early stages of migraine transformation.

An increase in the number of attacks per month is one of the main factors promoting migraine transformation.12 Approximately 50% of patients with episodic migraine present cutaneous allodynia between attacks, both in the trigeminal nerve territory (due to peripheral sensitisation) and in extra-trigeminal territories (due to central sensitisation).13 Therefore, any treatment able to reduce the frequency of migraine attacks and the resulting sensitisation may prevent transformation.

Trigeminal autonomic cephalalgiasThe clinical similarities between all trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias suggest a common pathophysiological mechanism. Pain and autonomic phenomena are thought to be caused by the involvement of the trigeminal and parasympathetic systems due to pathological activation of the trigeminal autonomic reflex.14 This reflex is modulated by the hypothalamus, which may explain the particular rhythmicity of these headaches. The trigeminovascular system is activated during TAC attacks, resulting in elevated plasma CGRP levels; the same occurs during migraine attacks.5,15

OnabotA may act on 2 levels to decrease pain signals in TACs: in peripheral sensory nerve terminals, it blocks the release of neuropeptides and neurotransmitters involved in nociception (CGRP, substance P, glutamate), and in the autonomic nervous system it modulates parasympathetic activity.16,17 Its effects on the autonomic nervous system have been described in a study of patients with chronic cluster headache receiving onabotA injections to the sphenopalatine ganglion, with satisfactory results.18

Several case series and case reports in the literature suggest that onabotA may be useful for preventive treatment of cluster headache, hemicrania continua, paroxysmal hemicrania, and short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attack with conjunctival injection and tearing (SUNCT).19–21 The injection protocols (injection site, dose) used in these articles are not homogeneous, and only a partial response was achieved. In any case, it should be noted that onabotA has been used in patients with TAC refractory to standard treatments. In view of the excellent tolerability of the drug, onabotA infiltration may be used in patients with refractory pain or poor response to oral treatment before resorting to more invasive treatment options.

Nummular headacheDue to its particular localisation, nummular headache is thought to be of epicranial origin, secondary to involvement of sensory nerve endings in the scalp or cranium.22 OnabotA is particularly suitable for this type of headache due to the ease of access to the peripheral nerve endings responsible for the pain. Several case reports and case series have consistently demonstrated the effectiveness of onabotA for nummular headache.23

Trigeminal neuralgiaApproximately 90% of cases of classical trigeminal neuralgia are caused by compression or distortion of the trigeminal nerve root by a blood vessel, which results in demyelination of the root at the area of entry into the pons. Approximately 5%–10% of all cases of trigeminal neuralgia are secondary to such other processes as tumours, multiple sclerosis, or ischaemia, which distort or injure trigeminal pathways at the central or peripheral level. In all cases, the underlying mechanism is hyperexcitability of trigeminal nerve fibres and transmission of ephaptic impulses from the fibres conveying tactile information to those transmitting painful stimuli.24 The effectiveness of onabotA in animal models of neuropathic pain justifies using the drug for trigeminal neuralgia.25 Furthermore, onabotA infiltration to peripheral nerves may contribute to the desensitisation of trigger points.

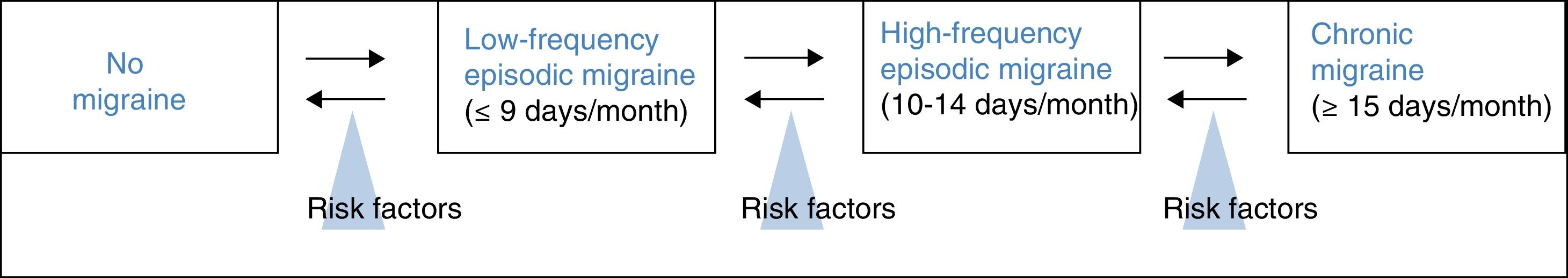

Treatment of high-frequency episodic migraine with onabotulinumtoxinAHFEM is defined by a frequency of 10 or more headache days per month, but fewer than 15 days per month, the minimum required to diagnose chronic migraine. It therefore reflects a transition between low-frequency episodic migraine and chronic migraine (Fig. 1).26 According to Torres-Ferrus et al.,27 HFEM shares more clinical and epidemiological characteristics and comorbidities with chronic migraine than with low-frequency episodic migraine.

In clinical practice, some patients with HFEM do not respond or tolerate preventive treatment. In these cases, we should consider other treatment options used in chronic migraine. Given the similarities between HFEM and chronic migraine, onabotA infiltration should be considered for patients with HFEM.28

The idea has been proposed in national and international congresses.29 In the case series mentioned above,27 patients with HFEM responded to onabotA, showing reduced pain frequency and intensity, analgesic use, and disability.

We recommend using onabotA dosed at 155–195 U in patients with HFEM, following the infiltration protocol established by the PREEMPT study group,30with infiltrations every 12 weeks in patients showing intolerance or lack of response to other preventive treatments for migraine.

Treatment of cluster headache with onabotulinumtoxinAThe first observations on the potential benefits of onabotA for cluster headache are made in isolated case reports. Freund and Schwartz31 injected 50 U of onabotA into the ipsilateral temporal region in 2 patients with episodic cluster headache. OnabotA infiltration was administered in the first week after cluster headache onset; pain resolved within 9 days, with the effects lasting 12 weeks. The only adverse drug reaction reported by patients was a subjective feeling of weakening of the masticatory muscles. In a series of patients with different types of treatment-resistant headache, Smuts and Barnard32 administered onabotA infiltration to 4 patients with cluster headache (whether headache was episodic or chronic is not indicated), reporting satisfactory results in 2 of them. In a more recent study, Robbins33 reported his experience with 6 patients with cluster headache refractory to conventional treatment (chronic in 4 cases and episodic in 2). He administered 24 U onabotA to the ipsilateral frontal and temporal regions (16 U) and the contralateral frontal region (8 U). Two patients with chronic cluster headache responded to treatment, with the effects lasting3–4 months. Benefits were observed nearly immediately after infiltration in both patients with episodic headache. More recently, Cesaretti et al.34 described the cases of 2 patients with episodic chronic cluster headache in whom the effects of onabotA lasted several years. These patients received 105−195 U of onabotA according to the PREEMPT protocol.30

The most relevant conclusions on the usefulness of onabotA for cluster headache are from a study by Sostak et al.19 The authors evaluated the efficacy and tolerability of onabotA in patients with cluster headache. The study included 12 male patients: 3 with episodic cluster headache and 9 with chronic cluster headache. OnabotA was added to each patient’s standard treatment for cluster headache. The authors administered 50 U onabotA to the ipsilateral temporalis (10 U), frontalis (10 U), splenius capitis (10 U), and trapezius muscles (20 U). Results were satisfactory in 3 patients with chronic cluster headache and none of the patients with episodic cluster headache. Progression time in the patients who responded to treatment was less than 2 years. One presented no further pain attacks, whereas the other 2 presented significant improvements in pain intensity and frequency. However, the authors were unable to suspend prophylactic medication for cluster headache in any of the patients. The effects of treatment lasted 2–3 months. The authors concluded that onabotA dosed at 50 U infiltrated to the pericranial muscles ipsilateral to pain may be an effective complementary treatment for chronic cluster headache. In another series from Hospital Vall D’Hebron in Barcelona,35 the authors infiltrated 155 U onabotA in 6 patients with chronic cluster headache, according to the PREEMPT protocol. Approximately 80% of patients reported decreased pain frequency, with changes in the temporal pattern (from chronic to episodic pain), and required less symptomatic medication.

No prospective, placebo-controlled clinical trials with representative samples have been conducted to date that may allow us to establish recommendations on the use of botulinum toxin for cluster headache. The benefits reported in the series cited may be explained by spontaneous remission of the disease; furthermore, a placebo effect cannot be ruled out. According to GECSEN’s guidelines, onabotA is a preventive treatment of unclear or doubtful efficacy in cluster headache due to the scarcity of scientific evidence.36

We recommend onabotA for patients with chronic cluster headache refractory to conventional treatment, before resorting to more invasive techniques. Although the dose and injection site are not precisely established, it seems reasonable to inject a minimum dose of 50 U into the frontal region bilaterally (to prevent undesired aesthetic consequences) and into the temporal, occipital, and cervical regions ipsilateral to the pain. The most recent series have followed the PREEMPT protocol with regard to the dose, injection site, and frequency of infiltration.30

Treatment of other trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias with onabotulinumtoxinAHemicrania continua and paroxysmal hemicrania are 2 types of primary headache included in the section on TACs in the ICHD-3 Beta.4 Both are characterised by strictly unilateral pain and ipsilateral autonomic symptoms, although some series have reported different patterns of pain location.37,38

Complete response to indometacin is a diagnostic criterion in both entities. However, up to 30% of patients present adverse drug reactions (mainly gastrointestinal problems),39 and 20% discontinue treatment.40 The literature also includes cases of headache with features typical of hemicrania continua or paroxysmal hemicrania but showing no response to indometacin.41–44 In the series of patients with hemicrania continua published to date,42,43 the frequency of indometacin non-responders ranges from 31% to 61%; this rate is 5% among patients with paroxysmal hemicrania.38 Pareja et al.45,46 propose a nosological model of continuous unilateral headaches that includes both hemicrania continua with response to indometacin and indometacin-resistant hemicrania continua (hemicrania incerta).

Nearly all non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have been tried in patients with paroxysmal hemicrania; at equipotent doses, none has achieved the extraordinary effects of indometacin. Other drugs showing different degrees of efficacy include aspirin, piroxicam, naproxen, celecoxib, rofecoxib, flunarizine, verapamil, acetazolamide, and corticosteroids.36 Verapamil and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs constitute the best alternatives in patients intolerant to indometacin (level of evidence IV, grade of recommendation C). Patients with hemicrania continua who are intolerant to indometacin may respond well to such COX-2 inhibitors as celecoxib, rofecoxib, and etoricoxib.36

Following the publication of isolated cases,47,48 Miller et al.20 published the results of an open-label study including 9 patients with hemicrania continua who had shown intolerance to indometacin, presenting gastrointestinal problems (8 patients) or pain exacerbation (2). All patients received onabotA infiltration over at least 2 cycles at 12-week intervals (2–6 cycles), following the PREEMPT protocol (mean dose, 167 U; range, 110−185 U). The authors report a >50% decrease in the number of moderate-to-severe headache days in 55.5% of patients; the effects lasted a mean of 11 weeks (range, 6−20). Patients receiving indometacin (44.4%) when onabotA treatment was started were able to discontinue this treatment. The authors also report improvements in headache-related disability scores. Regarding chronic paroxysmal hemicrania, one report describes good response to infiltration of 30 U onabotA to the ipsilateral temporal region.49

The case of a patient with refractory SUNCT showing response to onabotA infiltration has also been published. The patient received 40 U onabotA at 4 injection sites around the orbit ipsilateral to the pain (10 U per site), presenting no adverse reactions; the response persisted over several months and after several cycles.50 In 2016, Zhang et al.21 published their experience with onabotA in a 12-year-old patient with new-onset SUNCT; the patient received 70 U onabotA around the ipsilateral orbit, temporal region, cheek, and upper gingiva (2.5−5 U at each site, separated by 15 mm). The patient showed good tolerance, with complete response to a single cycle of onabotA infiltration; the pain resolved within a week and no recurrences were reported after 17 months of follow-up.

We recommend using onabotA in patients with hemicrania continua or paroxysmal hemicrania showing poor tolerance to indometacin or lack of response to standard doses or second-line treatments; the PREEMPT protocol should be followed (dose and frequency of infiltration).30Although the current evidence is from isolated cases, treatment with onabotA may be useful in patients with refractory SUNCT, either in monotherapy or as an adjuvant treatment at lower doses (40–70 U), with infiltrations in the ipsilateral side.

Treatment of nummular headache with onabotulinumtoxinANummular headache is not a rare entity, and affects 4.6% of all patients attended at headache units51 and 6% of patients consulting due to strictly unilateral pain.52

The pathophysiological mechanism of nummular headache is yet to be fully understood. Its precise localisation, the associated sensory alterations, and the presence of local trophic changes in some cases suggest that pain is of peripheral origin. Algometry studies have shown a lower pain threshold exclusively in the symptomatic area, even in patients with multifocal nummular headache.53,54 However, the condition is not associated with increased sensitisation of epicranial nerves, as demonstrated by the lack of response to anaesthetic peripheral nerve block.55 We may therefore assume that nummular headache is associated with epicranial small-fibre nerve dysfunction, with no involvement of the peripheral nerve trunk; peripheral mechanoreceptors may constitute the source of the pain and a potential therapeutic target in these patients.

No clinical trial of symptomatic or preventive treatments for nummular headache has been conducted to date. GECSEN’s guidelines recommend gabapentin (600−1200 mg/day) as the preventive treatment of first choice (level of evidence IV, grade of recommendation C).56 Poor response to such other oral preventive treatments as amitriptyline and topiramate is reported in at least 10 patients, and isolated case reports describe varying results with nortriptyline, clomipramine, lamotrigine, duloxetine, valproate, phenytoin, pregabalin, oxcarbazepine, and carbamazepine.55 However, response to oral preventive treatments is insufficient in nearly 20% of patients.51

The literature includes several descriptions of patients with nummular headache treated with onabotA. Seo and Park57 administered 10 U of onabotA to the painful area in 14 patients, achieving a reduction in visual analogue pain scale scores in all 14. Mathew et al.23 administered onabotA to 4 female patients who had shown no response to gabapentin and/or anaesthetic nerve block; the drug was injected at a dose of 2.5 U in 10 sites in or around the painful area (total dose: 25 U), achieving pain relief in all cases, with similar results when the procedure was repeated. Dusitanond and Young58 used onabotA (10−25 U) to treat 5 female patients with nummular headache presenting lack of response to oral preventive treatment or anaesthetic nerve blocks; 3 patients responded to onabotA treatment. Ruscheweyh et al.59 treated a woman with onabotA (the procedure is not described), achieving a marked reduction in pain intensity.

The largest series of patients with nummular headache treated with onabotA published to date includes 19 patients (14 women) showing poor response or intolerance to oral preventive treatment; 80% achieved at least partial improvements after one session of onabotA. The researchers injected onabotA dosed at 12.5−50 U into several sites in the symptomatic area.60

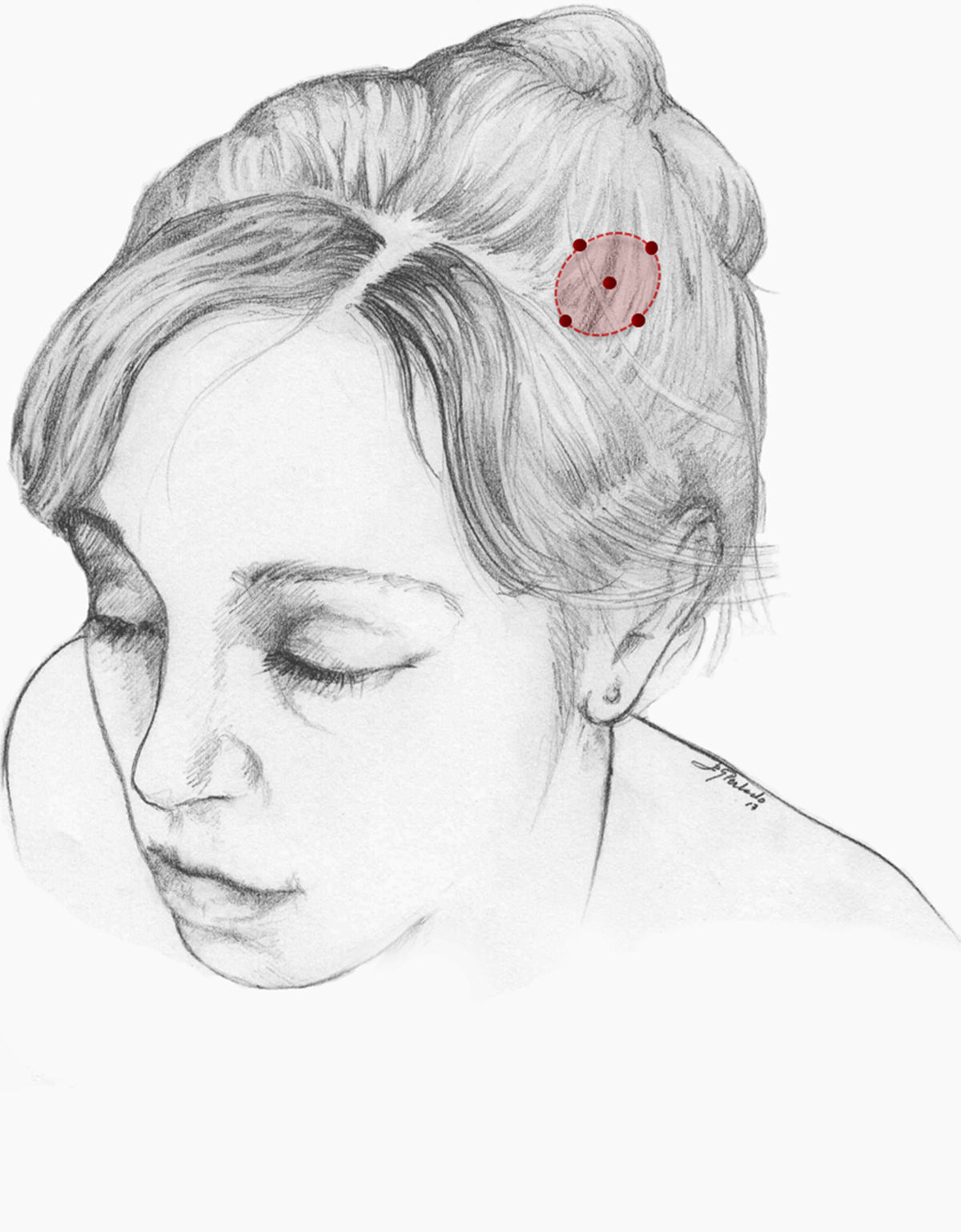

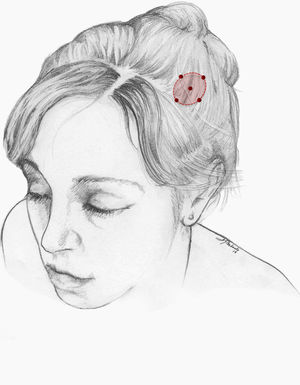

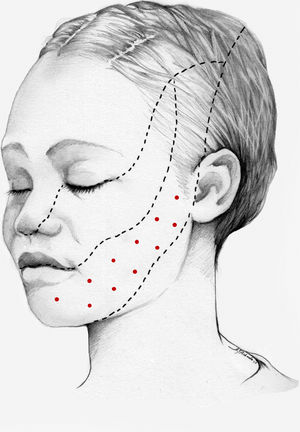

We recommend onabotA for patients with nummular headache who present intolerance or lack of response to oral preventive treatments, particularly gabapentin. OnabotA may also be considered the first treatment option in elderly patients. A reasonable treatment protocol consists of injections of 2.5−5 U per site at 5 different sites (4 in the periphery of the symptomatic area and the remaining one in the centre), as recommended in GECSEN’s guidelines (Fig. 2). The dose and number of injection sites depend on the size of the symptomatic area. Injections on both sides of the skull along the frontal or occipital region, as established by the PREEMPT protocol,30should be considered to prevent adverse reactions in those locations.

Treatment of trigeminal neuralgia with onabotulinumtoxinAThe analgesic effects of onabotA in patients with trigeminal neuralgia were first described in 1998.61 Numerous case reports, case series, open-label studies, and more recently randomised placebo-controlled studies have since been published. Seven open-label studies have been conducted, in all cases including patients with drug-resistant trigeminal neuralgia receiving a single dose of onabotA. The study by Li et al.62 included 88 patients with classical trigeminal neuralgia affecting a single branch, who were followed up for 14 months. The authors injected 25–170 U onabotA into the symptomatic area (2.5−5 U per site, separated by 15 mm). At 3 months, 52% of patients presented complete symptom resolution; at 14 months, 39% continued to show treatment response and 25% were completely asymptomatic.

In 2016, Xia et al.63 published the results of an open-label study including 87 patients with similar characteristics (13 had undergone invasive treatment). Patients received injections in 15–20 sites on the symptomatic side, separated by 15 mm (the dose administered is not indicated). At 8 weeks, the rate of response, defined as a decrease ≥ 50% on visual analogue pain scale scores, was 80%.

Since 2011, 5 randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies have been published of patients with classic trigeminal neuralgia receiving a single onabotA infiltration (25–75 U) and followed up for 8 weeks to 3 months (Table 2).64–69 In 2014, Zhang et al.67 published the largest clinical trial conducted to date. The study randomly assigned 84 patients to 3 groups: placebo (28 patients), 25 U onabotA (27), and 75 U onabotA (29). At 8 weeks, the response rate in each group was 32%, 70%, and 86%, respectively. Differences between the 2 onabotA groups were not significant. The main adverse reactions to onabotA infiltration, also reported in other studies, were facial asymmetry, weakness of the masticatory muscles, and palpebral ptosis. In all cases, symptoms were mild and transient. In 2014 a new clinical trial of onabotA was started in patients with refractory classic trigeminal neuralgia; the results are yet to be published.70

In an open-label study published in 2017, a single dose of 70–100 U onabotA (44 patients with trigeminal neuralgia) was compared against 2 doses of 50–70 U onabotA separated by 2 weeks (37 patients). At 6 months, no significant differences were observed between groups in terms of pain frequency, visual analogue pain scale scores, time from treatment to pain relief, or adverse reactions. However, response duration was significantly longer in the group receiving a single dose of onabotA.71 Finally, Cuadrado et al.72 successfully treated 4 patients with atypical odontalgia using a dose of 15–30 U distributed across 6–12 sites in the gums, hard palate, and upper lip. This suggests that onabotA has multiple therapeutic applications for facial pain other than trigeminal neuralgia. In patients with trigeminal neuralgia, infiltration of onabotA to trigger points inside the oral cavity may be a successful approach, enabling lower doses and preventing undesired aesthetic effects.

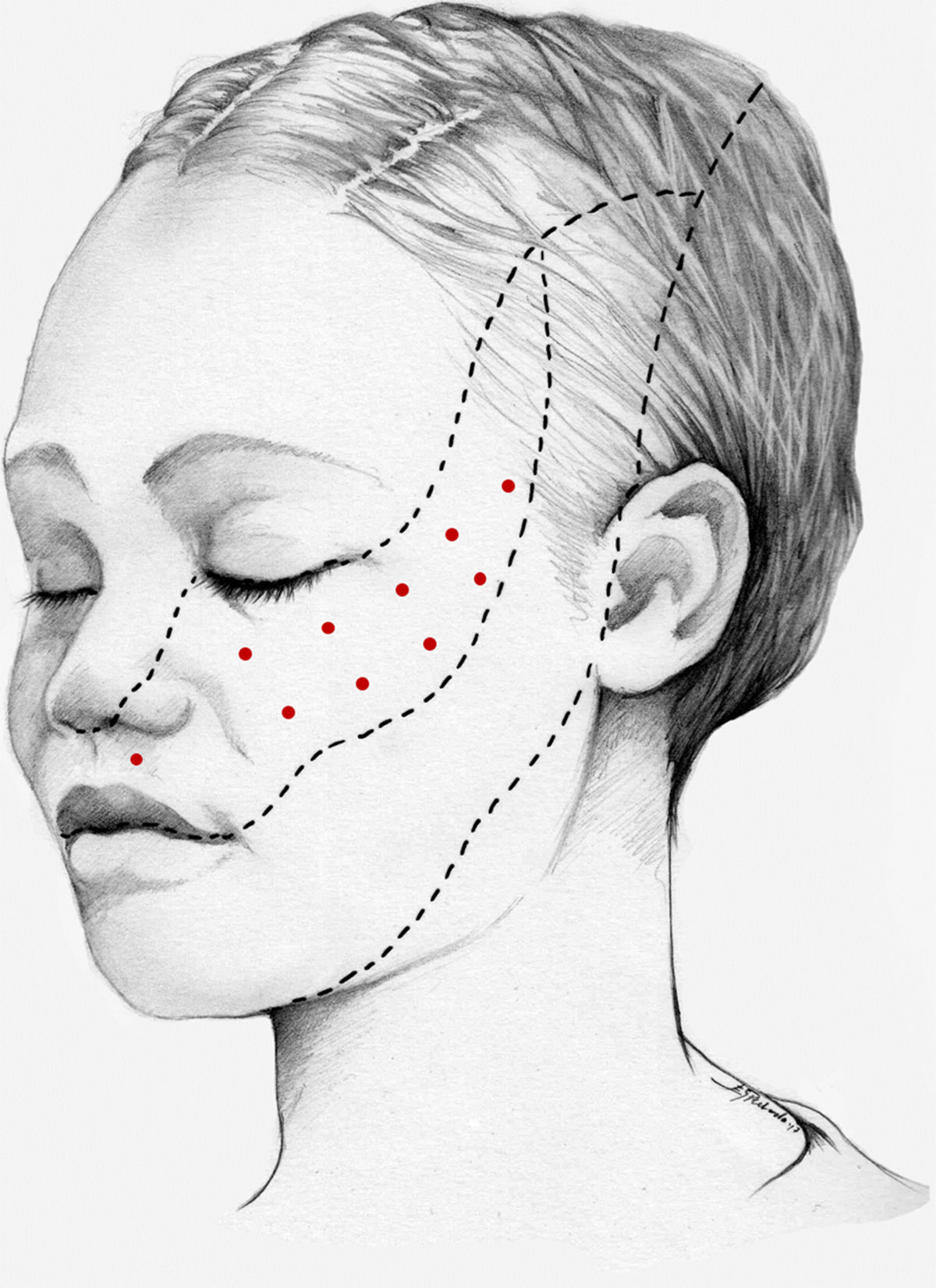

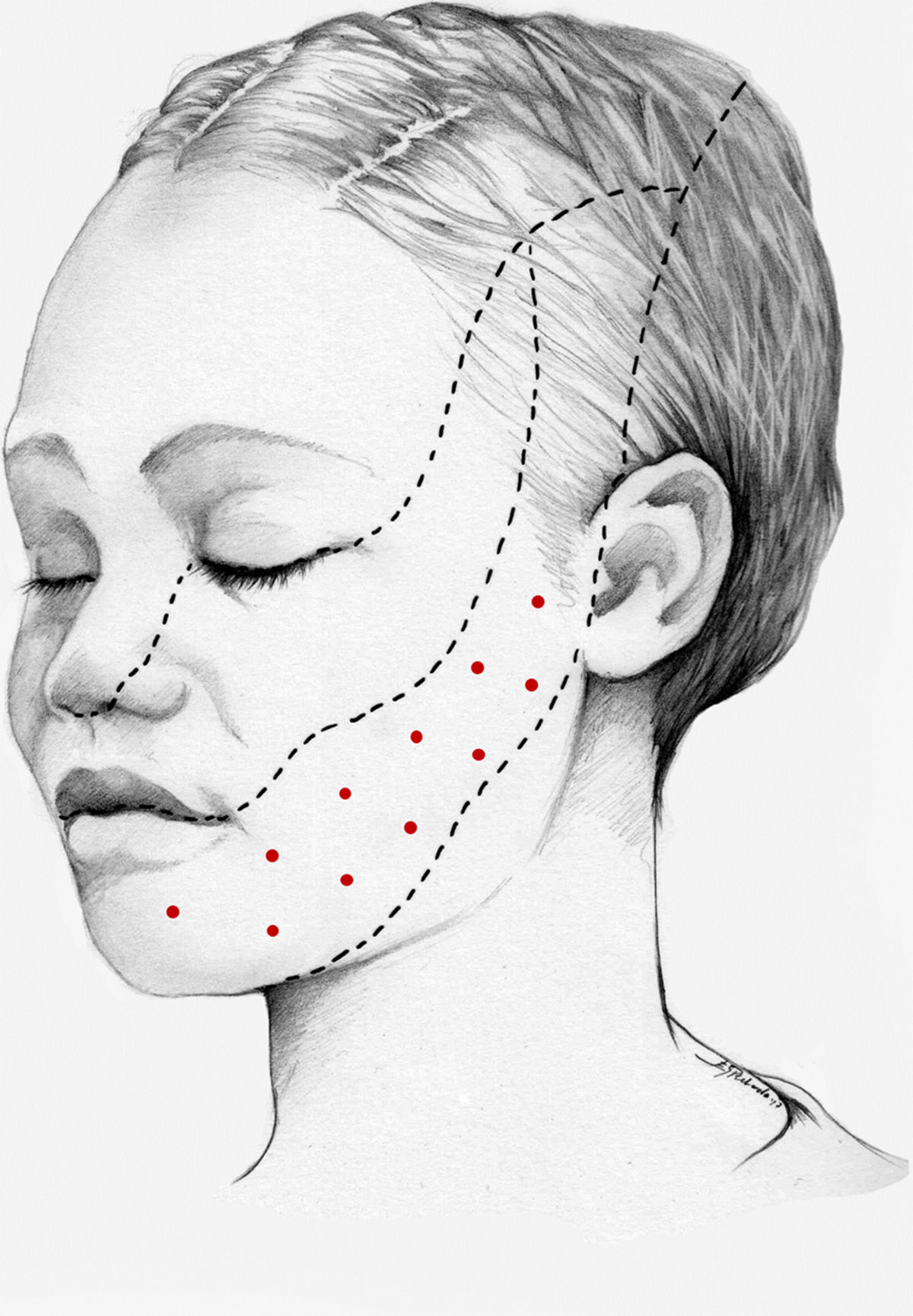

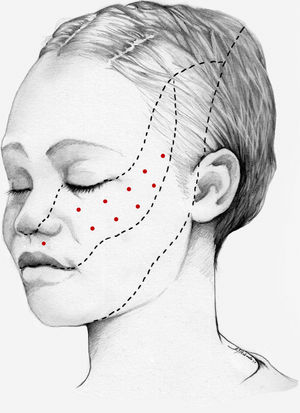

We recommend using 25–75 U onabotA in patients with drug-resistant classical trigeminal neuralgia, with 2.5−5 U administered per site, at 15 mm of separation, in the symptomatic area (Fig. 3 and 4). The area of injection may include trigger points inside the oral cavity. The dose should be adjusted according to the size of the area of infiltration, appearance of any adverse reactions, and patient response. OnabotA injection to some sites on the contralateral side should also be considered to reduce facial asymmetry. Although evidence regarding the most appropriate frequency of infiltration is inconclusive, a minimum period of 12 weeks between cycles seems a reasonable approach.

This study received no funding of any kind.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We would like to thank Esperanza González Perlado for her involvement in the project and for her beautiful drawings.

Please cite this article as: Santos-Lasaosa S, Cuadrado ML, Gago-Veiga AB, Guerrero-Peral AL, Irimia P, Láinez JM, et al. Evidencia y experiencia del uso de onabotulinumtoxinA en neuralgia del trigémino y cefaleas primarias distintas de la migraña crónica. Neurología. 2020;35:568–578.