Orofacial and cervical pain are a frequent reason for neurology consultations and may be due to multiple pathological processes. These include Eagle syndrome (ES), a very rare entity whose origin is attributed to calcification of the stylohyoid ligament or elongation of the temporal styloid process. We present a series of five patients diagnosed with ES.

MethodsWe describe the demographic and clinical characteristics and response to treatment of 5 patients who attended the headache units of 2 tertiary hospitals for symptoms compatible with Eagle syndrome.

ResultsThe patients were 3 men and 2 women aged between 24 and 51, presenting dull, intense pain, predominantly in the inner ear and the ipsilateral tonsillar fossa. All patients had chronic, continuous pain in the temporal region, with exacerbations triggered by swallowing. Four patients had previously consulted several specialists at otorhinolaryngology departments; one had been prescribed antibiotics for suspected Eustachian tube inflammation. In all cases, the palpation of the tonsillar fossa was painful. Computed tomography scans revealed an elongation of the styloid process and/or calcification of the stylohyoid ligament in 3 patients. Four patients improved with neuromodulatory therapy (duloxetine, gabapentin, pregabalin) and only one required surgical excision of the styloid process.

ConclusionsEagle syndrome is a rare and possibly underdiagnosed cause of craniofacial pain. We present 5 new cases that exemplify both the symptoms and the potential treatments of this entity.

El dolor orofacial y cervical es un motivo de consulta frecuente, que puede deberse a múltiples procesos patológicos. Entre ellos se encuentra el síndrome de Eagle, entidad muy infrecuente cuyo origen se atribuye a una osificación del ligamento estilohioideo o una elongación de la apófisis estiloides. Presentamos una serie de cinco pacientes con dicho diagnóstico.

Material y métodosSe describen las características demográficas y clínicas de cinco pacientes atendidos en las Unidad de Cefaleas de dos hospitales terciarios por un cuadro compatible con síndrome de Eagle, y su respuesta a distintos tratamientos.

ResultadosSe trata de 3 varones y 2 mujeres, de entre 24 y 51 años, con dolor de localización predominante en un oído y la región amigdalina ipsilateral, de cualidad sorda y de gran intensidad. En todos ellos el patrón temporal era crónico y continuo, con exacerbaciones desencadenadas por la deglución. Cuatro pacientes habían realizado múltiples consultas en servicios de otorrinolaringología, y uno de ellos había recibido tratamiento antibiótico ante la sospecha de tubaritis. En todos los casos la palpación de la fosa amigdalina resultó dolorosa. En tres de los pacientes se demostró elongación de la apófisis estiloides y/o calcificación del ligamento estilohioideo mediante tomografía computarizada. Cuatro mejoraron con tratamiento neuromodulador (duloxetina, gabapentina, pregabalina) y sólo uno precisó cirugía con escisión de la apófisis estiloides.

ConclusionesEl síndrome de Eagle es una causa de dolor cráneo-facial poco frecuente, y posiblemente infradiagnosticada. Aportamos cinco nuevos casos que permiten delimitar tanto la semiología como los posibles tratamientos.

Orofacial and neck pain is a frequent reason for neurological consultation, and may be associated with a wide range of pathological processes. One such disorder is Eagle syndrome, a controversial, underdiagnosed entity whose diagnostic criteria have been modified in successive editions of the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD).

This rare neurological syndrome is characterised by craniofacial and neck pain secondary to elongation and/or angulation of the styloid process or calcification of the stylohyoid ligament. These radiological findings are sometimes detected incidentally.

Material and methodsWe present a series of 5 cases of Eagle syndrome, hoping to contribute to the current knowledge of the clinical signs and symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment of this condition.

ResultsPatient 1Patient 1 was a 19-year-old man with a 3-year history of dull pain on the left side of the neck. Pain fluctuated in intensity, with exacerbations, and occasionally radiated to the ear, causing odynophagia and foreign body sensation in the pharynx. Pain intensity increased progressively, reaching an intensity of 8/10 on the visual analogue scale (VAS). The patient did not present nausea, vomiting, phonophobia, photophobia, ptosis, pupillary changes, tearing, or conjunctival injection, and pain was not exacerbated by exertion. The main trigger factors were forced opening of the mouth and yawning. A general and neurological examination revealed no remarkable alterations except for intense pain upon compression of the left tonsillar fossa. Results from a complete blood count, biochemical analysis, and coagulation study were normal. The patient tested negative for syphilis, Borrelia, and HIV. A head and neck MRI scan, scintigraphy, and Doppler ultrasound of the supra-aortic trunks revealed no alterations. Symptoms did not improve with indometacin, carbamazepine, valproate, flunarizine, or beta blockers. The patient underwent a skull base CT scan due to suspicion of stylalgia (Eagle syndrome). CT images revealed elongation of the left styloid process, which measured approximately 50mm (Fig. 1). Given the lack of response to several years’ conservative treatment, the styloid process was surgically removed, and symptoms resolved. The patient remains asymptomatic after 2 years of follow-up.

Patient 2Our second patient was a 24-year-old man with a 7-year history of bilateral temporal pain, located inside the ears. The patient experienced pain on a daily basis, predominantly in the morning. Pain was of mild intensity (3-4 on the VAS), and responded poorly to such analgesics as paracetamol or ibuprofen. The patient did not report irradiation of pain, nausea, vomiting, phonophobia, or photophobia; pain did not change with effort and was not associated with any other symptoms. Our patient was a smoker (15 cigarettes a day); he had been diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis at the age of 8 years and had presented an episode of pericarditis at the age of 18 years, which had resolved completely. He was receiving alprazolam (0.5mg) and clomipramine (25mg) to treat anxiety-depressive disorder. The general and neurological examination identified no alterations except for pain upon palpation of the neck muscles, coinciding with myofascial trigger points and the temporomandibular joint (the patient had been diagnosed with temporomandibular joint dysfunction 3 years previously). He had since been using a mouth splint, with no clear improvement. Pain was most severe upon palpation of the tonsils, and intensified with swallowing. Complementary tests revealed only a mild increase in rheumatoid factor levels, with no other relevant findings in the blood analysis, immunological study, or serology tests. A head and neck MRI scan showed no alterations; a CT scan displayed calcification of both stylohyoid ligaments; the length of both styloid processes was within the normal range. Symptoms were controlled satisfactorily with gabapentin dosed at 300mg every 8hours.

Patient 3Our third patient was a 38-year-old woman with history of dyslipidaemia and generalised anxiety, and was receiving bromazepam dosed at 1.5mg. She complained of a one-year history of pain in the left tonsillar fossa, radiating to the left ear. Pain was sudden-onset, stabbing, continuous, and of moderate intensity (5/10 on the VAS), with occasional exacerbations (7/10 on the VAS) lasting several hours. Exacerbations were associated with greater levels of stress. Pain intensity did not increase when eating or swallowing, and pain did not present at night, allowing proper rest. Episodes were not associated with any other symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, phonophobia, or photophobia. Metamizole and ibuprofen did not relieve pain. The patient was first attended by the otorhinolaryngology department; ear, nose, and throat disorders were ruled out by larynx CT and head and neck MRI. The neurological examination identified no alterations except for pain upon palpation of the left tonsillar fossa, associated with mild hyperaemia. The patient did not present pain upon palpation of other pericranial structures or the temporomandibular joint. A CT scan of the skull base and neck showed normal length and angulation of both styloid processes, and calcifications along the left stylohyoid ligament. The patient was diagnosed with probable Eagle syndrome and prescribed indometacin (25mg every 8hours) and amitriptyline (10mg at night). Pain worsened after 2 months of treatment, and topiramate (50mg every 12hours) was added to her treatment regime. The patient’s mood also worsened; her psychiatrist added diazepam 5mg at night and sertraline 50mg at breakfast, and discontinued amitriptyline. The patient reports considerable improvements after several months of treatment; pain episodes occur approximately every 2 months and are of moderate intensity.

Patient 4Patient 4 was a 41-year-old former smoker with no relevant medical history. He came to the neurology department due to pain in the left side of the neck, radiating to the ipsilateral ear and occasionally to both ears. Pain was dull, reaching an intensity of 7/10 on the VAS; episodes were triggered by swallowing. The patient presented no autonomic symptoms, nausea, or vomiting. He had been diagnosed with left Eustachian tube dysfunction; symptoms did not improve with antibiotics. He reported pain upon palpation of both tonsillar fossae. Complementary tests (blood test, immunological studies, serology tests, and head and neck MRI) detected no alterations. A skull base CT scan revealed elongation of the left styloid process (52mm) and calcification of the ipsilateral stylohyoid ligament. The patient was diagnosed with Eagle syndrome and treated with indometacin dosed at 25mg every 12hours; the dose could not be increased due to gastrointestinal intolerance. This treatment partially controlled the symptoms. Gabapentin dosed at 300mg with every meal achieved complete symptom control; the patient remains nearly asymptomatic after 2 years of follow-up.

Patient 5The final patient was a 51-year-old woman with history of mandibular fracture due to a traffic accident 5 years before symptom onset. She complained of pain in the right retropharyngeal area and right side of the neck, radiating to the external auditory canal and occasionally to the right side of the upper lip. Pain was dull, constant, and sometimes stabbing; intensity was moderate-to-severe on most occasions (6/10 on the VAS), increasing during exacerbations. It was not accompanied by autonomic or neurological symptoms, nausea, or vomiting. Pain was mainly triggered by swallowing; the patient had reduced her food intake, losing 5kg in 3 months. The maxillofacial surgery department attributed the pain to the previous trauma; as conventional analgesics failed to control pain, the patient was referred to the neurology department. The patient presented pain upon palpation of the right tonsillar fossa; the neurological and general examination revealed no other relevant findings. Complementary tests (blood analysis, immunological study, serology tests, head and neck MRI) returned normal results. A skull base CT scan revealed elongation of the right styloid process (45mm). Treatment with pregabalin dosed at 75mg every 12hours achieved complete symptom control.

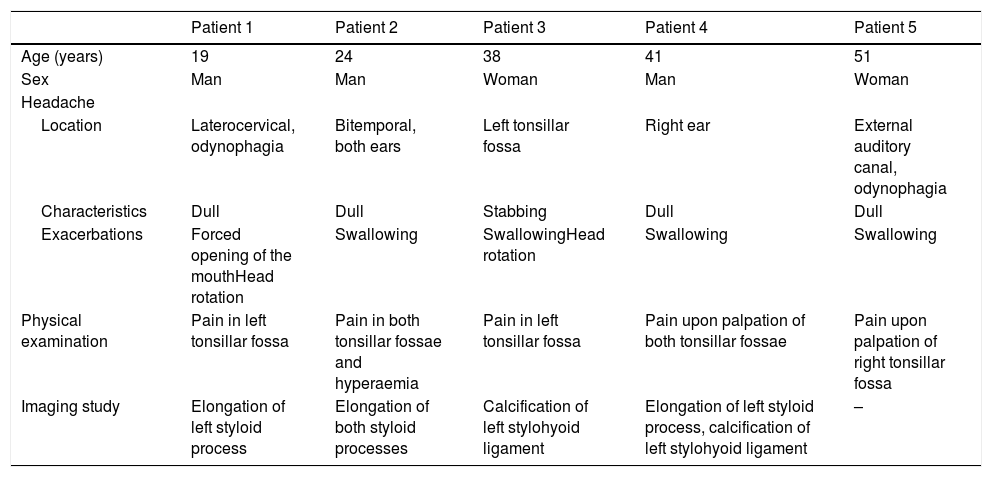

Table 1 summarises the demographic and clinical characteristics of our 5 patients.

Demographic, clinical, and radiological data from our series of patients.

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 19 | 24 | 38 | 41 | 51 |

| Sex | Man | Man | Woman | Man | Woman |

| Headache | |||||

| Location | Laterocervical, odynophagia | Bitemporal, both ears | Left tonsillar fossa | Right ear | External auditory canal, odynophagia |

| Characteristics | Dull | Dull | Stabbing | Dull | Dull |

| Exacerbations | Forced opening of the mouthHead rotation | Swallowing | SwallowingHead rotation | Swallowing | Swallowing |

| Physical examination | Pain in left tonsillar fossa | Pain in both tonsillar fossae and hyperaemia | Pain in left tonsillar fossa | Pain upon palpation of both tonsillar fossae | Pain upon palpation of right tonsillar fossa |

| Imaging study | Elongation of left styloid process | Elongation of both styloid processes | Calcification of left stylohyoid ligament | Elongation of left styloid process, calcification of left stylohyoid ligament | – |

Eagle syndrome is a clinical syndrome characterised by facial, oropharyngeal, and/or neck pain secondary to elongation of the styloid process and/or calcification of the stylohyoid ligament. Diagnosis is based on both clinical and radiological findings. The syndrome was first included in the ICHD in the third edition (beta version; 2013) within group 11 (headache or facial pain attributed to disorder of the cranium, neck, eyes, ears, nose, sinuses, teeth, mouth, or other facial or cervical structures). Subgroup 11.8, head or facial pain attributed to inflammation of the stylohyoid ligament, refers to Eagle syndrome as the previous term used to refer to this condition. Diagnostic criteria are as follows1:

- A

Any head, neck, pharyngeal, and/or facial pain fulfilling criterion C

- B

Radiological evidence of calcified or elongated stylohyoid ligament

- C

Evidence of causation demonstrated by at least 2 of the following:

- 1

pain is provoked or exacerbated by digital palpation of the stylohyoid ligament

- 2

pain is provoked or exacerbated by head turning

- 3

pain is significantly improved by local injection of local anaesthetic agent to the stylohyoid ligament, or by styloidectomy

- 4

pain is ipsilateral to the inflamed stylohyoid ligament

- 1

- D

Not better accounted for by another ICHD-3 diagnosis.

Recognition of this condition as a discrete entity, which was not the case in the 2 previous versions of the ICHD, has assisted in clinical detection. Furthermore, it has helped to unify diagnostic criteria, given that few reviews on the topic have been published and address the condition from very different perspectives: from the viewpoint of neurology or neurosurgery to those of odontology or maxillofacial surgery. Diagnosis is based on 3 necessary criteria: a clinical criterion, a radiological criterion, and a causal relationship (this is a necessary condition for the syndrome to be included in the group of secondary headaches). This aids in the recognition and correct definition of the disease, clearly differentiating it from other entities.

Eagle syndrome was first described in 1937 by the German otorhinolaryngologist Watt Eagle, whose clinical and radiological definition of the condition is still in use. Eagle described the syndrome as facial, neck, or laryngeal pain associated with elongation of the ipsilateral styloid process, with or without calcification of the stylohyoid ligament. He described the syndrome in a series of patients undergoing tonsillectomy; this explains the different theories of the pathophysiology of the disease. According to the most widely accepted hypotheses, microtraumas in this area (eg, tonsillectomy) cause metaplastic changes and small foci of granulation tissue, mainly at the insertion of the ligament, which transforms into bone tissue.2–5

The styloid process is a long, slender piece of bone on the internal surface of the skull base, extending from the temporal bone posterior to the mastoid process; its length and direction vary greatly. It is located close to the jugular foramen and the carotid canal, which play a key role in the pathophysiology of the syndrome. Three muscles arise from the styloid process: the stylohyoid muscle, innervated by the facial nerve; the stylopharyngeus muscle, innervated by the glossopharyngeal nerve; and the styloglossus muscle, innervated by the hypoglossal nerve. Two ligaments also arise from the styloid process: the stylohyoid and the stylomandibular ligaments. The medial part of the styloid process is linked to the internal carotid artery, the maxillary artery, the internal jugular vein, the glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves, and trigeminal and facial nerve branches; the posterolateral and inferior parts are linked to the hypoglossal nerve and the lateral cervical sympathetic chain.6–8

The styloid process is elongated in 6% to 7% of the population; elongation is bilateral in many cases, and is usually asymptomatic.9,10 According to some series, asymptomatic elongation of the styloid process has a prevalence of up to 30%, if calcified stylohyoid ligament is also considered. Symptomatic cases are less frequent (4%-10%). Population studies show that the condition is more frequent among women aged 60 to 79 years.

Eagle syndrome has traditionally been classified into 2 main types. The classical type (type 1), as described by Eagle, is characterised by such symptoms as odynophagia, dysphagia, and foreign body sensation in the pharynx. Pain may present in any area from the side of the head to the ipsilateral chest. It is dull and constant, exacerbated by yawning or swallowing. Some patients present a mass, bulging from the pharyngeal mucosa. Classic Eagle syndrome is believed to be caused by intermittent compression neuropathy of the fifth, seventh, ninth, or tenth cranial nerves. The glossopharyngeal nerve is the most frequently affected, and glossopharyngeal neuralgia is the main differential diagnosis. This frequently occurs after tonsillectomy.11–15

The carotid type (type 2) is caused by internal carotid artery compression, causing pain in the parietal region, face, and neck, exacerbated by contralateral rotation of the head. When the external carotid artery is affected, patients usually present constant neck pain radiating to the eye, exacerbated upon ipsilateral head rotation. Compression of the internal carotid artery, known as carotidynia, is characterised by headache radiating from the occipital pole to the orbit of the eye. Symptoms are associated with irritation of the pericarotid sympathetic plexus. Carotid-type Eagle syndrome may be associated with transient ischaemic attacks upon head turning, or even carotid artery dissection.16

In addition to physical examination, diagnosis of Eagle syndrome requires optimal imaging of the styloid process, mainly through neck and skull base CT scans.6,10 Contrast CT is recommended not only to estimate the length and thickness of the styloid process but also to evaluate its anatomical relationship with muscles and blood vessels.10,15,17–19 Dynamic studies of neck flexion and extension may be used to study compression. Simple radiography is no longer the diagnostic test of choice.

A styloid process measuring longer than 30mm is considered to be elongated. This factor must be associated with abnormal angulation of the process and/or calcification of the ligament.6 An elongated styloid process is an incidental finding in healthy individuals; therefore, it is not pathognomonic for Eagle syndrome. Pain is caused by compression of different structures, depending on the angulation of the stylohyoid process. Lateral angulation may compress the external carotid artery at its bifurcation into the maxillary and the superficial temporal artery. Posterior angulation may compress the last 4 cranial nerves, the internal carotid artery, or the jugular vein. Medial or anterior angulation compresses the tonsillar fossa and may irritate the mucosa or structures located in that region.6,20–22

Differential diagnosis includes glossopharyngeal neuralgia, occipital neuralgia, temporomandibular joint dysfunction, dental problems, tonsillitis or mastoiditis, and migraine. Other potential diagnoses include hyoid bursitis, Sluder syndrome, oesophageal diverticula, temporal arteritis, and vertebral arteritis.6,13,23 During clinical history taking, Eagle syndrome may be suspected if the patient reports neck and facial pain exacerbated by neck flexion and extension or contralateral head rotation. The most relevant finding of a physical examination is pain in the tonsillar fossa; when elongation is severe, symptoms may be recreated by palpating the styloid process.

Glossopharyngeal neuralgia may cause shorter, more severe episodes of pain. In these cases, pain is located in the oropharynx and intensifies upon swallowing, speech, and tongue movement.

The first-line treatment for Eagle syndrome involves neuromodulators used for other types of neuralgia: gabapentin, amitriptyline, valproic acid, carbamazepine, or corticosteroid injection into the region of the tonsillar fossa. The use of corticosteroid injections has increased in recent years. Surgery (styloidectomy) is only indicated in cases of refractory pain where other methods have failed.6,24

ConclusionAlthough our sample is small, the cases presented here contribute to further delimitation of the clinical and radiological diagnostic criteria, exploratory findings, and management of Eagle syndrome. We analysed these cases from a classic viewpoint, retrospectively assessing whether the patients met the new ICHD-3 beta criteria. All patients met radiological criteria for Eagle syndrome (elongation of the styloid process, calcification of the ligament, or both).

All 5 had classical (type 1) Eagle syndrome; this is the only type included in the ICHD-3 beta. Carotid (type 2) Eagle syndrome, attributed to compression of pericarotid sympathetic fibres by the elongated process, was not seen in our case series; this type is rarer and is not included in the ICHD-3 beta definition of Eagle syndrome. Although both types have the same aetiology, they should be regarded as distinct entities since they are semiologically different. Semiology is the starting point for the ICHD.

If Eagle syndrome is suspected, the physician should compress the tonsillar fossa; pain upon palpation of the tonsillar fossa ipsilateral to the elongated styloid process is a diagnostic criterion of the condition. Palpation sometimes reveals a bulge in the area, which corresponds to the protruding styloid process. One of the new diagnostic criteria is pain improvement after local anaesthetic infiltration.

In terms of imaging studies, a CT scan of the neck and skull base (with 3D reconstruction, where possible) constitutes the optimal technique not only for estimating the length and thickness of the process but also to determine its anatomical relationship with muscles and blood vessels.

Finally, infiltration of local anaesthetics is currently regarded as the treatment of choice for pain management. Our patients were treated with neuromodulators; one underwent surgery due to lack of response.

Eagle syndrome should be included in the differential diagnosis of any type of headache or facial, neck, or pharyngeal pain triggered or exacerbated by head rotation, when other more common causes have been ruled out. Glossopharyngeal neuralgia constitutes the main differential diagnosis for these symptoms. The ICHD-3 beta criteria are essential in unifying diagnostic criteria and recognising this controversial entity. However, some limitations remain, including a very broad description of pain (with no reference to the typical radiation to the ear) and the fact that head turning is the only trigger factor listed (according to published evidence, swallowing is a more frequent trigger). Our series complements the available evidence on this entity.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: González-García N, et al. Síndrome de Eagle hacia la delimitación clínica. Neurología. 2021;36:412–417.