Sturge-Weber syndrome (SWS), or encephalotrigeminal angiomatosis, is the most frequent neurocutaneous syndrome, characterised by vascular malformations which manifest sporadically. The full presentation includes brain vascular malformations (pial or leptomeningeal angioma), cutaneous abnormalities (facial angioma) and ocular abnormalities (choroidal angioma).1,2 We present the case of a patient with very-late-onset SWS who experienced acute confusional syndrome, convulsions, and homonymous hemianopsia.

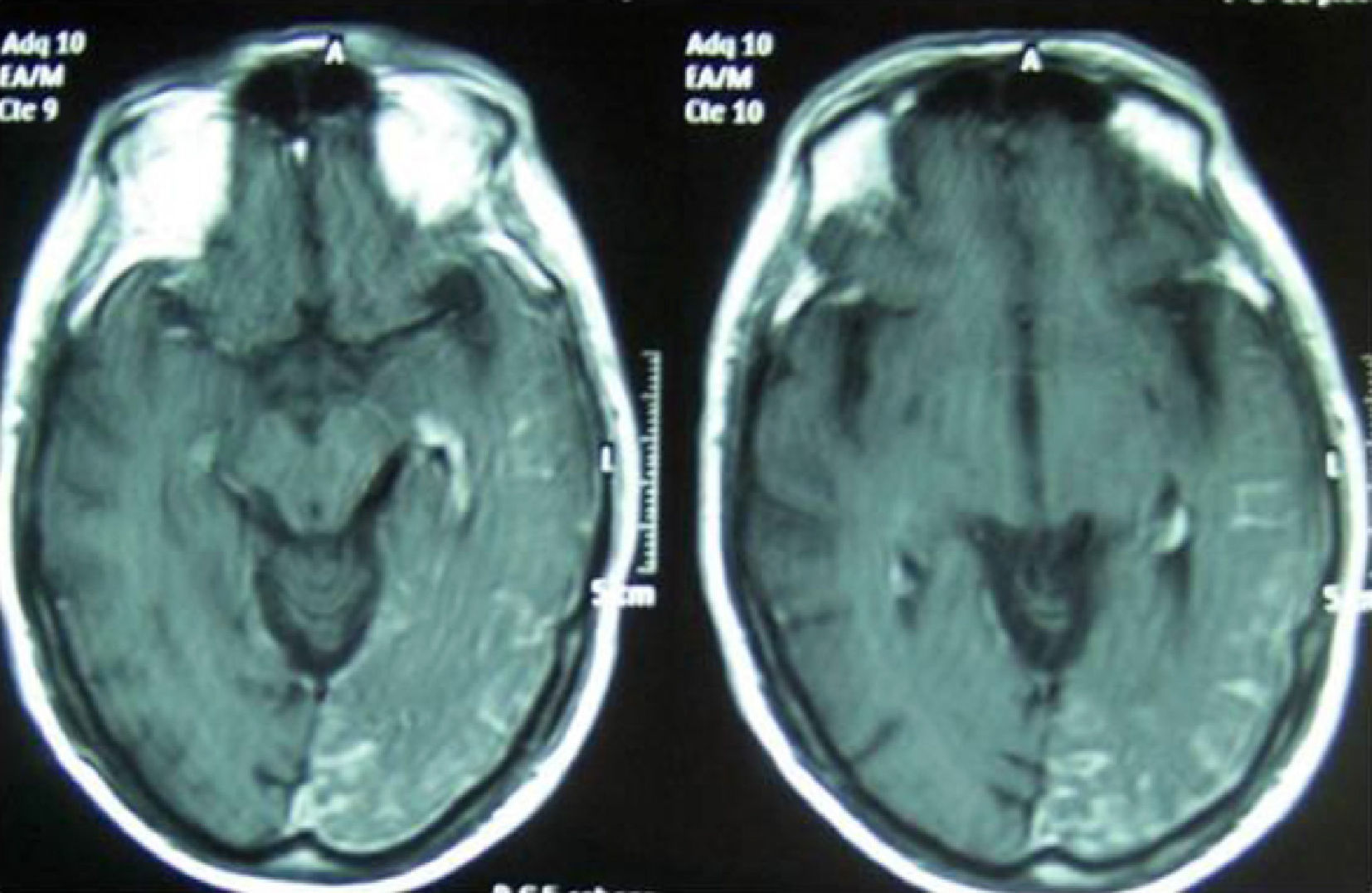

Our patient is a 64-year-old man, a former smoker, who drinks 80g ethanol/day and has a personal history of diabetes. In the 48hours prior to his admission, he presented confusional symptoms and altered conduct/behaviour. He arrived at the emergency department due to a generalised tonic-clonic seizure. Computed tomography in the emergency department did not show acute intracranial disease and lumbar puncture obtained acellular cerebrospinal fluid with a protein level of 73.3mg/dL. He was conscious, disoriented, and anxious at admission, presenting sensory aphasia and coprolalia. Doctors began treatment with intravenous levetiracetam. After 48hours, confusional symptoms resolved and the patient was oriented during the neurological examination, which revealed with bilateral horizontal nystagmus, right homonymous hemianopsia, right upper limb apraxia, and unsteady gait with tendency to drift to the right. The patient presented a small cutaneous angioma on the left frontal region (territory of the ophthalmic branch of the fifth cranial nerve) (Fig. 1). We consulted the ophthalmology service, which ruled out the presence of choroidal angioma. Seven days after, we performed a brain MRI scan that revealed a parenchymatous vascular malformation extending to the left parietal-temporal-occipital leptomeninges with atrophy of the underlying parenchyma. In the contrast sequences, we observed a prominence in the choroid plexus of the atrium of the left lateral ventricle connecting to a large drainage vein. This drainage vein follows a subependymal path before emerging at the medial surface of the temporal lobe and then draining into the vein of Galen. The study also discovered an extra-axial linear enhancement on the cortical sulci of the left occipital, posterior temporal, and parietal lobes (Fig. 2). The electroencephalogram (EEG) performed in the 72hours after hospital admission revealed paroxysmal activity at the left posterior temporal and occipital levels. The patient recovered well and hemianopsia and gait disorder resolved. Since starting the treatment with levetiracetam, he has not experienced further convulsions. A follow-up EEG performed after discharge showed that the paroxysmal activity present during the acute phase had disappeared.

Our patient presented several characteristics that might be considered atypical in a case of SWS. The first one is the late diagnosis, given that SWS is usually diagnosed in paediatric patients1,2,4; and the most frequent neurological symptoms are epileptic seizures, present in 75% to 90% of patients. Half of these patients experience seizures before the age of 1 year, and less than 10% of patients older than 5 have seizures.1,2

It is normal for leptomeningeal angioma to present ipsilateral to the cutaneous nevus. Although facial angioma more frequently affects the territory of the maxillary branch of the trigeminal nerve (V2),3 ocular and/or neurological symptoms only appear when the ophthalmic branch is affected (V1).1–4 In our patient, angioma affected a small part of the V1 territory, and for this reason, according to the study by Enjolras et al., the probability of it being associated with SWS was low. With a study population of 106 cases of facial port-wine stains, these authors determined that the risk of associated SWS was low in cases of partial involvement of the V1 territory. SWS was present in only 6% of these patients.4

SWS patients may present visual field alterations manifesting as hemianopsia or quadrantanopia, or even cortical blindness if the pial angioma affects the occipital cortex bilaterally. In our case, homonymous hemianopsia resolved in the following 3 weeks. We have found a similar case in the literature describing a patient diagnosed with SWS at the age of 45 who also presented homonymous hemianopsia that resolved after 3 months of follow-up.5 It is not easy to explain how hemianopsia resolved, but it may have been due to the inhibition of paroxysmal activity in the occipital region thanks to levetiracetam, which would mark it as an ictal-postictal symptom. Otherwise, it might have been due to resolution of the vasogenic oedema that may develop during an epileptic seizure.6 However, our brain MRI study was not able to test this second hypothesis. The same pathogenic mechanisms might be involved in the resolution of other symptoms, such as sensory aphasia and right arm apraxia.

Our clinical case makes us aware that SWS does not only manifest during childhood and that a port-wine stain in the CN V1 territory in a patient with focal neurological signs obliges us to screen for a pial vascular malformation typical of this syndrome.

Please cite this article as: García-Estévez D. Crisis convulsiva y hemianopsia homónima como forma de comienzo de un síndrome de Sturge-Weber en un hombre de 64 años. Neurología. 2014;29:379–380.