To determine the prevalence, impact and management of hypertension-mediated organ damage (HMOD) according to the presence of type 2 diabetes (T2DM).

MethodsIBERICAN is an ongoing multicenter, observational and prospective study, including outpatients aged 18–85 years who attended the Primary Care setting in Spain. In this study, the prevalence, impact and management of HMOD according to the presence of T2DM at baseline were analyzed.

ResultsAt baseline, 8066 patients (20.2% T2DM, 28.6% HMOD) were analyzed. Among patients with T2DM, 31.7% had hypertension, 29.8% dyslipidemia and 29.4% obesity and 49.3% had ≥1 HMOD, mainly high pulse pressure (29.6%), albuminuria (16.2%) and moderate renal impairment (13.6%). The presence of T2DM significantly increased the risk of having CV risk factors and HMOD. Among T2DM population, patients with HMOD had more dyslipidemia (78.2% vs 70.5%; P=0.001), hypertension (75.4% vs 66.4%; P=0.001), any CV disease (39.6% vs 16.1%; P=0.001) and received more drugs. Despite the majority of types of glucose-lowering agents were more frequently taken by those patients with HMOD, compared to the total T2DM population, the use of SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists was marginal.

ConclusionsIn patients daily attended in primary care setting in Spain, one in five patients had T2DM and nearly half of these patients had HMOD. In patients with T2DM, the presence of HMOD was associated with a higher risk of CV risk factors and CV disease. Despite the very high CV risk, the use of glucose-lowering agents with proven CV benefit was markedly low.

Determinar la prevalencia, impacto y manejo del daño orgánico mediado por hipertensión (HMOD) según la presencia de diabetes tipo 2 (DM2).

MétodosIBERICAN es un estudio multicéntrico, observacional y prospectivo, que incluye pacientes entre 18 y 85 años que acuden a consultas de atención primaria en España. En este estudio se analizó la prevalencia, el impacto y el manejo de la HMOD según la presencia de DM2 al inicio del estudio.

ResultadosSe analizaron 8,066 pacientes (20,2% DM2, 28,6% HMOD). Entre los pacientes con DM2, el 31.7% tenía hipertensión, el 29,8% dislipidemia, el 29,4% obesidad y el 49,3% tenía≥1 HMOD, principalmente presión de pulso elevada (29,6%), albuminuria (16,2%) e insuficiencia renal moderada (13,6%). La presencia de DM2 aumentó significativamente el riesgo de tener factores de riesgo cardiovasculares y HMOD. Entre la población con DM2, los pacientes con HMOD tenían más dislipidemia (78,2% frente a 70,5%; p=0,001), hipertensión (75,4% frente a 66,4%; p=0,001), cualquier enfermedad cardiovascular (39,6% frente a 16,1%; p=0,001) y recibieron más fármacos. A pesar de que los pacientes con HMOD tomaban con mayor frecuencia la mayoría de los tipos de agentes hipoglucemiantes, en comparación con la población total de DM2, el uso de inhibidores de SGLT2 y agonistas del receptor de GLP-1 fue marginal.

ConclusionesEn los pacientes atendidos diariamente en atención primaria en España, uno de cada 5 pacientes tenía DM2 y casi la mitad de estos pacientes tenían HMOD. En pacientes con DM2, la presencia de HMOD se asoció con un mayor riesgo de factores de riesgo cardiovasculares y enfermedad cardiovascular. A pesar del riesgo cardiovascular muy alto, el uso de agentes hipoglucemiantes con beneficio cardiovascular demostrado fue notablemente bajo.

Type 2 diabetes (T2DM) is a main health care problem in Spain.1,2 The Di@bet.es study showed a decade ago that the overall prevalence of DM adjusted for age and sex was around 14%, of which 6% had unknown DM.1 However, data from the IDF 2021 Diabetes Atlas showed that the number of people with DM in Spain had increased from 2.8 million in 2011 to 5.1 million in 2021.2 In addition, total diabetes-related health expenditure in 2021 in Spain was huge, accounting for $15.5 billion, $3000 per person with DM.2

The presence of DM doubles the risk of developing CV disease.3 The recent 2023 European guidelines for the management of CV disease in patients with T2DM consider that patients with clinically established atherosclerotic CV disease, or severe hypertension-mediated organ damage (HMOD), or 10-year CV disease risk≥20% using SCORE2-Diabetes have a very high CV risk.4 In other words, having severe HMOD could be considered an equivalent of CV disease. As a result, it is mandatory to improve the prevention and early detection of complications of patients with T2D, such as HMOD, through and holistic management to reduce the CV burden of this population.4–6 European guidelines define severe HMOD as the presence of any of the following conditions: estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR)<45mL/min/1.73m2 irrespective of albuminuria, eGFR 45–59mL/min/1.73m2 and albuminuria – previously named as microalbuminuria– (urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio [UACR] 30–300mg/g), proteinuria (UACR>300mg/g), or presence of microvascular disease in at least three different sites, such as albuminuria plus retinopathy plus neuropathy.4,7–9 Therefore, the search and identification of HMOD in patients with T2DM should be strengthened in clinical practice. In this context, it is important to ascertain the prevalence and impact of HMOD in real-life population with T2DM.

IBERICAN (Identificación de la poBlación Española de RIesgo CV y reNal – Identification of the Spanish population at risk of CV and renal disease–) is currently determining in more than 8000 subjects attended in primary care in Spain, the prevalence of CV risk factors and the incidence of CV events, after 10 years of follow-up.10–14 In this study, the prevalence, impact and management of HMOD according to the presence of T2DM at baseline were analyzed.

MethodsIBERICAN10–14 is an ongoing epidemiological, multicenter, observational and prospective study, which has included outpatients aged 18–85 years who attended the Primary Care setting of the National Health System in Spain, regardless of the presence of CV risk factors or CV disease, and who agreed to participate in the study by giving their written informed consent, with a follow-up for at least 10 years. Patients that changed the habitual residence to another city or country within the first six years after inclusion, with terminal disease, a life expectancy less than five years, or manifest difficulties to be followed-up were excluded from the study. The study was approved by the Independent Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Clínico San Carlos (Madrid, Spain) and was registered at https://clinicaltrials.gov under the number NCT02261441.

Data were collected from the electronic medical history of patients, direct interview and medical examination and were entered into an electronic Case Report Form (CRF) specifically created for the study. Sociodemographic data, CV risk factors (hypertension, dyslipidemia, smoking, obesity, sedentary lifestyle), HMOD (pulse pressure≥60mmHg in subjects>65 years of age, ankle brachial index<0.9, albuminuria: UACR between 30 and 299mg/g, eGFR [CDK-EPI] 30–59ml/min, left ventricular hypertrophy), and vascular disease (ischemic heart disease, heart failure, stroke, peripheral arterial disease and chronic kidney disease) were recorded. All variables were defined according to the 2013 European Society of Hypertension/European Society of Cardiology guidelines.15 Physical examination included blood pressure, heart rate, and body mass index. Data from a 12-lead electrocardiogram and blood and urine tests (glycaemia, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, creatinine, uric acid and UACR) performed according to clinical practice in the previous 6 months before inclusion were considered valid for the study. Total number of drugs, as well as the type of glucose-lowering agents (metformin, sulphonylureas, glinides, glitazones, dipeptidyl peptidase 4 [DPP-4] inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists [GLP-1 RA], sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 [SGLT2] inhibitors, insulin and others) were also recorded. A good glycemic control was considered as HbA1c≤7%.16 Obesity was defined as a body mass index>30kg/m2, and sedentarism as doing physical less than 30min daily of physical activity or absence of activity.

Statistical analysisQualitative variables were defined by their absolute and relative frequencies, and continuous variables as mean and standard deviation. Statistical tests were performed according to the nature of the variables. To study the relationship between the categorical variables, the Chi-squared test was used (where more than 20% of the cells had an expected frequency of less than five, Fisher's exact test was performed). Student's t-test was used to compare continuous variables between groups. Multivariate analyses were performed to determine those factors associated with an increased risk of CV risk factors and HMOD according to the presence of T2DM and among patients with T2DM, those factors associated with an increased risk of CV risk factors and CV disease according to the presence of HMOD. All those variables that showed a P-value<0.05 in the bivariate analysis were included as independent variables in the initial model. From the initial model, the non-significant variables were manually eliminated, until the final model was reached. All comparisons rejected the null hypothesis with an alpha error<0.05. IBM SPSS version 22.0 was used for data analyses.

ResultsOf the total of 8066 patients included in the IBERICAN study at baseline, 8056 (99.9%) were valid for the analysis. Of these, 20.2% had T2DM and 28.6% HMOD.

Among patients with T2DM, 35.6% had a sedentary lifestyle, 31.7% hypertension, 29.8% dyslipidemia, and 29.4% were obese. In addition, 49.3% had at least one HMOD, mainly high pulse pressure (29.6%), albuminuria (16.2%) and moderate renal impairment (13.6%) (Table 1). The prevalence of any HMOD was similar between men and women, but albuminuria was more common in men (20.6% vs 10.8%; P<0.001) and moderate renal impairment in women (11.7% vs 16.1%; P=0.01) (Table 2). Control of DM was numerically higher in patients with HMOD, but without significant statistical differences (74.4% vs 66.2%; P=0.81), and time of evolution of DM was significantly greater in those patients with HMOD (≥10 years: 47.3% vs 34.7%, ≥15 years: 21.8% vs 14.7%; P<0.001).

Baseline clinical characteristics according to the presence of T2DM.

| T2DM (20.2%) | No T2DM (79.8%) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biodemographic data | |||

| Age, years | 65.5±10 | 55.9±15 | <0.001 |

| Sex (male), % | 55.5 | 42.9 | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | |||

| Hypertension, % | 31.7 | 9.6 | 0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia, % | 29.8 | 10.4 | 0.001 |

| Obesity, % | 29.4 | 15.3 | 0.001 |

| Smoking, % | 15.2 | 21.3 | 0.001 |

| HMOD | |||

| Any | 49.3 | 23.5 | <0.001 |

| PPa, mmHg | 29.6 | 13.5 | <0.001 |

| Albuminuria, % | 16.2 | 5.5 | <0.001 |

| Moderate renal insufficiencyb, % | 13.6 | 5.7 | <0.001 |

| LVH, % | 7.3 | 3.1 | <0.001 |

| ABI<0.9, % | 2.8 | 1.4 | <0.001 |

| Physical examination | |||

| Waist circumference, cm | 103.3±15.0 | 94.7±14.5 | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.5±5.2 | 28.0±5.4 | <0.001 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 134.4±15.8 | 127.63±15.7 | <0.001 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 76.9±10.1 | 76.59±10.3 | 0.271 |

| HR (lpm) | 74.7±11.1 | 73.0±10.8 | <0.001 |

| Biochemical parameters | |||

| Glycemia (mg/dL) | 137.6±43.0 | 93.4±13.2 | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 177.2±39.6 | 199.4±38.4 | <0.001 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 49.0±14.1 | 56.5±15.3 | <0.001 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 100.9±36.9 | 121.2±34.1 | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 147.9±87.8 | 118.8±76.2 | <0.001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.93±0.5 | 0.85±0.5 | <0.001 |

| UACR (mg/g) | 1.2±0.5 | 1.1±0.3 | <0.001 |

| Uric acid | 5.5±1.5 | 5.2±1.5 | <0.001 |

ABI: ankle brachial index; BMI: body mass index; HR: heart rate; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; LVH: left ventricular hypertrophy; PP: pulse pressure; SBP: systolic blood pressure; T2DM: type 2 diabetes mellitus; HMOD: hypertension-mediated organ damage; UACR: urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio.

Prevalence of HMOD in patients with T2DM according to sex.

| Total | Men (55.7%) | Women (44.3%) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any | 49.3 | 48.8 | 49.9 | 0.688 |

| PPa, mmHg | 29.6 | 28.7 | 30.8 | 0.35 |

| Albuminuria, % | 16.2 | 20.6 | 10.8 | <0.001 |

| Moderate renal insufficiencyb, % | 13.6 | 11.7 | 16.1 | 0.01 |

| LVH, % | 7.3 | 7.4 | 7.1 | 0.77 |

| ABI<0.9, % | 2.8 | 2.2 | 3.6 | 0.10 |

ABI: ankle brachial index; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; LVH: left ventricular hypertrophy; PP: pulse pressure; T2DM: type 2 diabetes mellitus; HMOD: hypertension-mediated organ damage.

With regard to the biochemical parameters in patients with T2DM, mean glycemia was 137.6±43.0mg/dL, mean LDL cholesterol 100.9±36.9mg/dL, mean creatinine 0.9±0.5mg/dL and mean UACR 1.2±0.5mg/g (Table 1). Compared to patients without T2DM, patients with T2DM had more CV risk factors and HMOD (Table 1). The presence of T2DM significantly increased the risk of having CV risk factors (hypertension, dyslipidemia and obesity) and HMOD (any HMOD, including high pulse pressure, albuminuria, moderate renal disease, left ventricular hypertrophy and ankle brachial index<0.9) (Table 3). Except in very elderly patients, the prevalence of HMOD increased with age, in both patients with and without T2DM (supplementary Fig. 1).

Risk of cardiovascular risk factors and HMOD in patients with T2DM (vs no T2DM).

| OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular risk factors | ||

| Hypertension, % | 4.36 | 3.86–4.94 |

| Dyslipidemia, % | 3.64 | 3.22–4.11 |

| Obesity, % | 2.31 | 2.07–2.58 |

| Smoking, % | 0.67 | 0.57–0.78 |

| HMOD | ||

| Any | 2.42 | 2.22–2.63 |

| PPa, mmHg | 2.69 | 2.37–3.06 |

| Albuminuria, % | 3.34 | 2.81–3.95 |

| Moderate renal insufficiencyb, % | 2.62 | 2.19–3.13 |

| LVH, % | 2.45 | 1.94–3.10 |

| ABI<0.9, % | 2.08 | 1.45–2.98 |

ABI: ankle brachial index; CI: confidence interval; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; LVH: left ventricular hypertrophy; PP: pulse pressure; OR: Odds Ratio; T2DM: type 2 diabetes mellitus; HMOD: hypertension-mediated organ damage.

Among patients with T2DM, with regard to CV risk factors, patients with HMOD (vs no HMOD) had more dyslipidemia (78.2% vs 70.5%; P=0.001), hypertension (75.4% vs 66.4%; P=0.001), and sedentarism (38.6% vs 32.6%; P=0.012). The risk was particularly high for hypertension (OR 2.78; 95% CI 2.18–3.54). Regarding CV disease, the presence of any CV disease, ischemic heart disease, peripheral artery disease, atrial fibrillation, heart failure, and stroke was more frequent in those patients with HMOD compared to those without HMOD, particularly peripheral artery disease (OR 4.77; 95% CI 3.12–7.31) and heart failure (OR 3.50; 95% CI 2.21–5.55) (Table 4).

Prevalence and risk of cardiovascular risk factors and HMOD in patients with T2DM according to the presence of HMOD.

| HMOD | NO HMOD | OR | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular risk factors | |||||

| Dyslipidemia, % | 78.2 | 70.5 | 1.5 | 1.20–1.88 | 0.001 |

| Hypertension, % | 75.4 | 66.4 | 2.78 | 2.18–3.54 | 0.001 |

| Obesity, % | 52.5 | 49.8 | 1.11 | 0.91–1.35 | 0.289 |

| Sedentarism, % | 38.6 | 32.6 | 1.3 | 1.06–1.60 | 0.012 |

| Smoking, % | 11.2 | 15.2 | 0.7 | 0.53–0.94 | 0.018 |

| Cardiovascular disease | |||||

| Any cardiovascular disease, % | 39.6 | 16.1 | 3.43 | 2.71–4.34 | 0.001 |

| Ischemic heart disease, % | 17.2 | 7.8 | 2.43 | 1.78–3.33 | 0.001 |

| Peripheral artery disease, % | 14.5 | 3.4 | 4.77 | 3.12–7.31 | 0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation, % | 13.9 | 5.4 | 2.83 | 1.96–4.07 | 0.001 |

| Heart failure, % | 10.0 | 3.1 | 3.50 | 2.21–5.55 | 0.001 |

| Stroke, % | 9.1 | 3.1 | 3.16 | 1.98–5.04 | 0.001 |

CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; T2DM: type 2 diabetes mellitus; HMOD: hypertension-mediated organ damage.

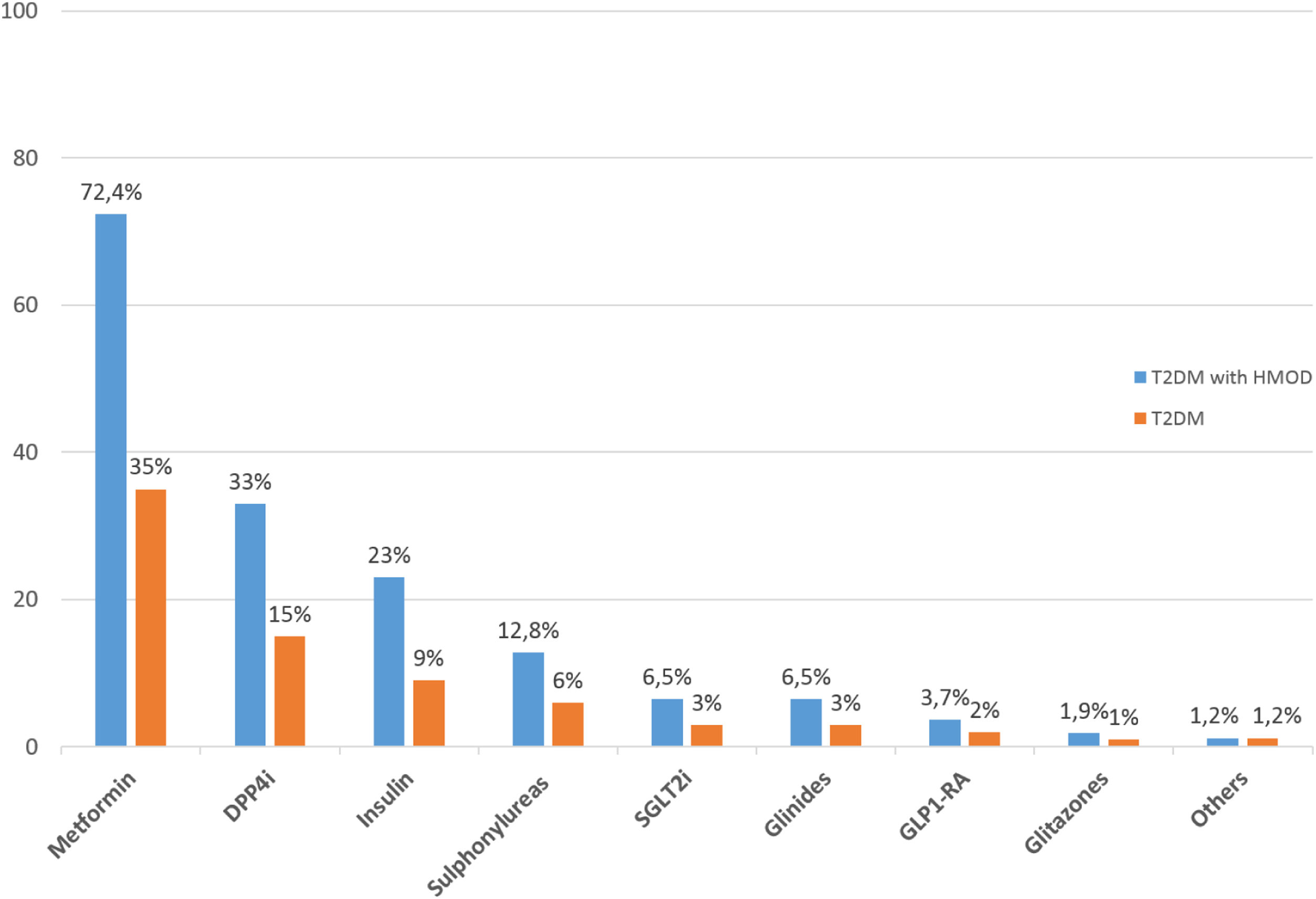

The number of antidiabetic drugs taken by patients with T2DM according to the presence of HMOD is presented in Fig. 1. Those patients with HMOD received more drugs than those without HMOD (bitherapy: 32.8% vs 30.4%; 3 drugs 14.8% vs 12.4%; P<0.001). In the overall population with T2DM, the most common glucose-lowering agents prescribed were metformin (35%), dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitors (15%) and insulin (9%). Only 3% of patients were taking SGLT2 inhibitors and 2% GLP-1 RA. The majority of types of glucose-lowering agents were more frequently taken by those patients with HMOD, compared to the total T2DM population (Fig. 2).

Glucose-lowering agents in patients with T2DM and HMOD (vs total T2DM population). DPP4i: dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitors; GLP1-RA: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists; SGLT2i: sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors; T2DM: type 2 diabetes mellitus; HMOD: hypertension-mediated organ damage.

Our study showed that among patients daily attended in primary care setting in Spain, around one in five patients had T2DM and nearly half of these patients had also HMOD. In patients with T2DM, the presence of HMOD was associated with a higher risk of CV risk factors and CV disease. Despite this high CV risk, the use of glucose-lowering agents with proven CV benefit was markedly low.

Different studies, such as ENRICA, DARIOS, ESCARVAL, or FRESCO, among others, have analyzed CV risk factors or CV disease in Spain. Unfortunately, these studies are outdated, not reflecting the current epidemiology of T2DM, have focused on particular populations or some risk factors in isolation, or have analyzed only specific regions of Spain.17–21 By contrast, IBERICAN is currently analyzing the distribution of CV risk factors and the incidence of CV disease in adult population attended in primary care throughout Spain. Therefore, IERICAN is a large nationwide study, in which more than 500 investigators have included more than 8000 patients, making this study representative of the Spanish population attended in primary care setting.22

In our study, 20% of patients had T2DM. In these patients, around one third had hypertension, and 30% dyslipidemia and obesity. As expected, the presence of CV risk factors and HMOD was more common in this population, compared to patients without T2DM. This is in line with previous studies that have shown that the management of patients with T2DM is challenging, as these patients have many comorbidities, particularly CV risk factors and HMOD.23,24

The presence of T2DM significantly increased the risk of having CV risk factors, particularly hypertension (OR 4.4) and dyslipidemia (OR 3.6). Of note, these diabetes-associated conditions share bidirectional pathogenic relationships.25 Thus, the incidence of hypertension increases markedly in patients with T2DM through different mechanisms, including the hyperactivation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and the sympathetic nervous system, oxidative stress, inflammation, endothelial dysfunction or abnormal sodium processing in the kidneys.26 Hypertension in patients with T2DM markedly increases the risk of CV events and appropriate control with combined therapy, on the top of renin angiotensin system inhibition is mandatory.26,27 On the other hand, patients with T2DM exhibit high plasma triglycerides and small dense LDL cholesterol levels, as well as a low HDL cholesterol concentration, leading to a more proatherogenic lipid profile.25 Therefore, attaining LDL cholesterol recommended targets through intensive lipid lowering therapy seems essential to reduce CV burden in diabetic population.4

T2DM also increased the risk of having HMOD. In fact, the prevalence of HMOD raised from 23.5% in patients without T2DM (28.6% in the general population) to 49.3% among patients with T2DM (OR 2.42). The most common HMOD found in T2DM population were high pulse pressure (29.6%), followed by albuminuria (16.2%) and moderate renal dysfunction (13.6%). High pulse pressure, defined as the difference between systolic and diastolic blood pressure, is the clinical manifestation of arterial stiffness and is more frequent in patients with T2DM. In fact, high pulse pressure has been associated with a higher risk of mortality in patients with T2DM.28,29 Albuminuria and renal impairment are two common early complications in the evolution of T2DM. According to the last European guidelines, the concomitance of both conditions in patients with T2DM are considered as very high CV risk, regardless of SCORE2-Diabetes.4,30 As guidelines recommend, patients with T2DM should be routinely screened for kidney disease by assessing eGFR and UACR.4,31 Although less than 10% of patients with T2DM exhibited left ventricular hypertrophy and low ankle brachial index, both conditions markedly increase the risk of MACE, and should be routinely ruled out in all patients with T2DM, particularly in those patients with other CV risk factors, such as hypertension.32–34 A recent study has shown in a Mediterranean region of Spain, that the majority of patients with T2DM have other CV risk factors, and that half of them have a very high CV risk and 40% a high CV risk (less than 10% have moderate CV risk).35 Therefore, as guidelines recommend, the presence of severe HMOD should be screened in every patient with T2DM.4 Moreover, our study showed that among patients with T2DM, those patients with HMOD exhibited more CV risk factors (except smoking), and any CV disease, regardless of the vascular bed (i.e., ischemic heart disease, stroke or peripheral artery disease). As a result, it is obligatory the clinical assessment of atherosclerotic vascular disease in patients with T2DM on a regular basis, particularly when HMOD are present. Of note, stricter goals and intensification of treatment are required in these patients.4 On the other hand, although some studies have suggested a different CV risk in patients with T2DM according to sex, mainly due to hormonal factors or different artery diameter, the fact is that more than a half of patients with T2DM have a very high CV risk, regardless of sex.35,36 Moreover, our study showed that although albuminuria was more common in men and moderate renal impairment in women, the prevalence of any HMOD was similar regardless of gender and a similar approach should be performed in men and women.

Guidelines recommend an optimal and holistic management of patients with T2DM with the control of all comorbidities, including CV risk factors with specific goals, and CV disease.4–6 With regard to the antihyperglycemic treatment, in the light of evidence, the therapeutic management has been moved from a glucocentric approach, to a CV and renal protection approach in addition to metabolic control.4,37 Thus, different meta-analyses have shown that both SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists provide CV benefits in patients with T2DM, particularly in those with a high or very high CV risk, regardless of glycemic control or metformin use.38–40 In this context, international guidelines recommend tight glycemic control (HbA1c<7%) to reduce microvascular complications and also the use of glucose-lowering agents with proven CV benefits (i.e., SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists), mainly in patients at high/very high CV risk, such as those with HMOD.4,37 Unfortunately, our study showed that despite control of DM was numerically higher in patients with HMOD (74.4% vs 66.2%; P=0.81), the use of SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists was marginal in patients with T2DM and HMOD (6.5% and 3.7%, respectively). A higher use of these drugs with proven CV benefit should be promoted.

This study has some limitations. First, the lack of randomization of investigators, with the participation of the most motivated physicians in CV care, could have overestimated the control of CV risk factors. Moreover, although the definition of HMOD was carried out in accordance with the 2013 European Society of Hypertension/European Society of Cardiology guidelines, as it was an observational study of clinical practice, there may have been an underestimation in the detection of some of them, particularly albuminuria and ankle-brachial index. However, the high number of patients included could reduce this potential limitation. In addition, this was an observational study, without a control group and this may difficult to ascertain the impact of changes in the management of patients on the incidence of CV complications. Finally, patients were selected from primary care setting in Spain and this could limit the generalizability of the results to the overall Spanish population.

In conclusion, the presence of HMOD is common in patients with T2DM and is associated with a higher risk of having CV risk factors and CV disease. Despite these patients have a very high CV risk, the use of glucose-lowering agents with proven CV benefits was markedly low. Therefore, the search for HMOD in patients with T2DM should be strengthened in clinical practice. It is necessary to increase the awareness and knowledge of primary care physicians about the importance of the early identification of HMOD in this high risk population and the implementation of the more appropriate therapeutic approach in this population.

Authors’ contributionsConceptualization, methodology, writing-review and editing: AARS, JDE, MAPD, VPC, ABG, RMMP, JPG, SMVZ, VMS, ASF, LGM, VMAV, SCS; writing-original draft preparation: AARS, JDE, MAPD, VMAV, SCS and VPC; supervision: SMVZ, ABG, JPG, MAPD, ASF, RMMP, SCS and VPC; project administration: SCS; funding acquisition: VPC, SCS, MAPD, JPG, RMMP, VMS, SMVZ, ABG and LGM. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

FundingInvestigators, members of the Scientific Committee/Steering Committee, the General Coordinator, and the Principal Investigator have no received any honoraria for participating in the IBERICAN study. The IBERICAN study is financed by the SEMERGEN Foundation with its own funds. It has received grants to defray occasional expenses for statistical analysis and dissemination of results (Astra Zeneca, Menarini).

Conflict of interestAll the authors declare that they have no type of conflict of interest that may affect the contents of this article.

To the redGDPS Foundation for the financial support for this manuscript. To the SEMERGEN Foundation for financing the global IBERICAN study. To the researchers who have actively participated in the recruitment of patients. We also want to thank all patients for their participation in the study.