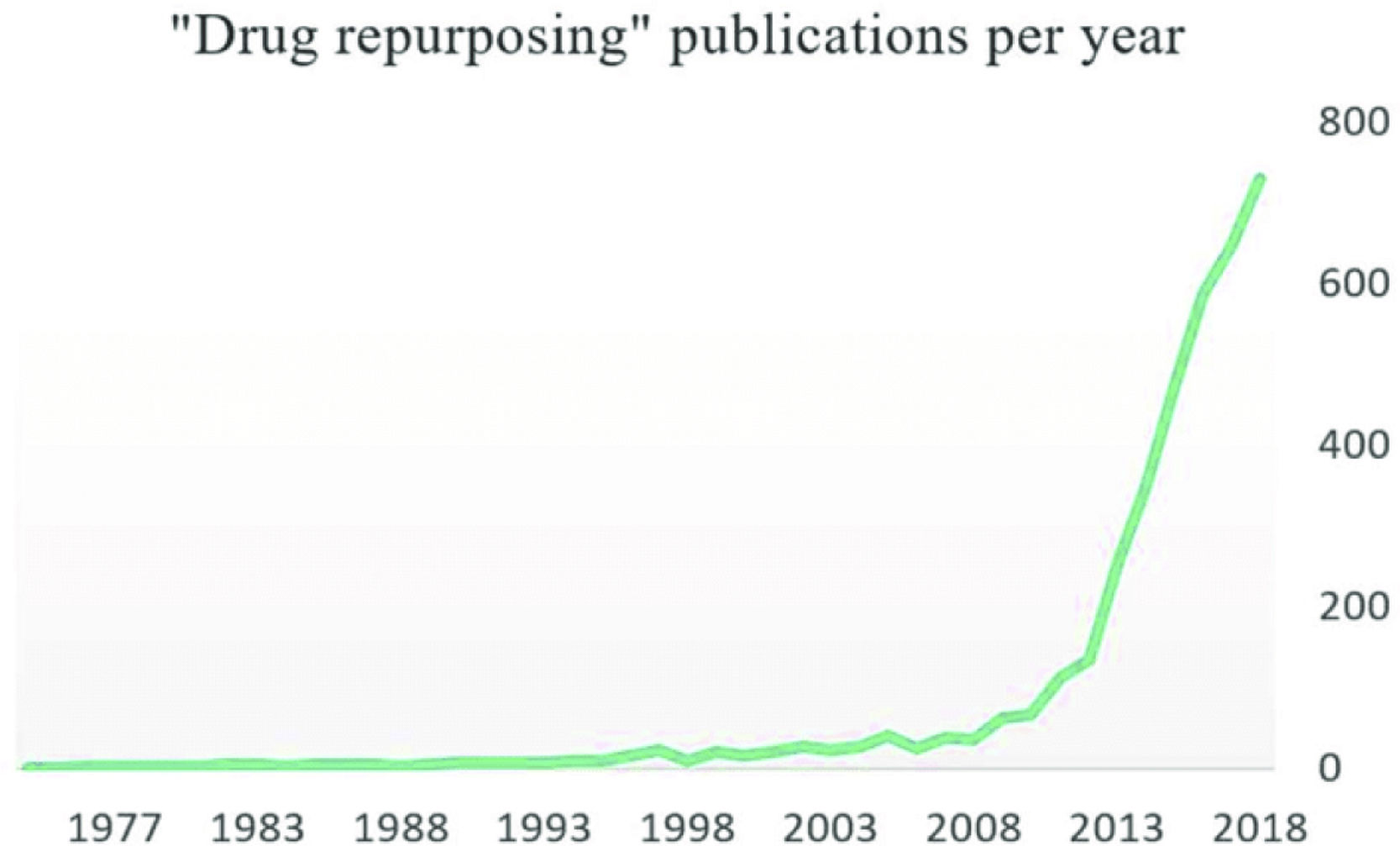

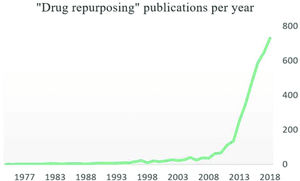

Drug repurposing (DRP) (also known as drug repositioning) means establishing new medical uses for already known drugs. Although this is not a new strategy, it has become more popular in the last decade (Fig. 1). One-third of marketing approvals in recent years correspond to DRP, and repurposed drugs currently render around 25% of the annual pharmaceutical industry revenue.1

Since new indications are built on previous knowledge, the drug development timeline is substantially shortened, the same applies for the required investment. In principle, if dose compatibility is found2 much of the preclinical testing, safety assessment, and even phase I clinical trials might be bypassed. However, efficacy for the new indication should be confirmed at preclinical and clinical levels. Testing safety for new indications should be done if drug–disease interactions are suspected.

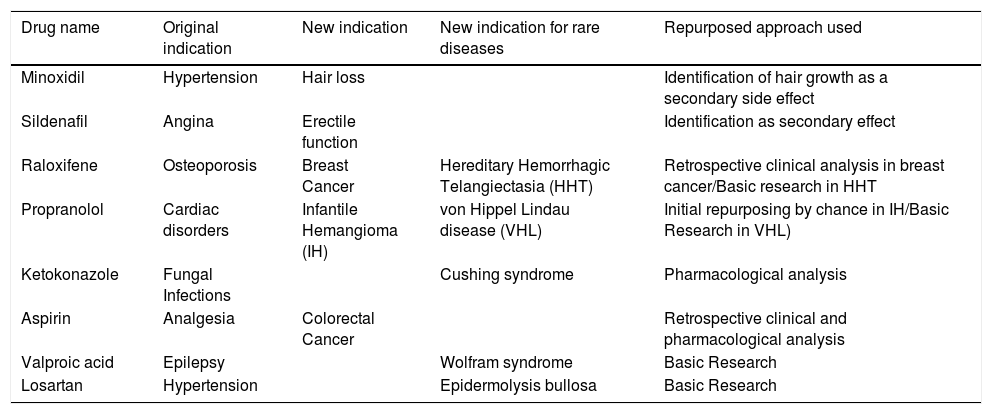

Most of the successful and best-known drug repurposing stories emerged from off-target effects problem (Table 1) from previous clinical indications, such as the use of sildenafil in erectile dysfunction instead of pulmonary hypertension and minoxidil in hair loss instead of only in hypertension Table 1.3 Recently, the drug discovery community has started systematic data based DRP approaches. Computational assistance is being increasingly used for signature matching of transcriptomic, proteomic and molecular structure data. At this moment virtual screenings based on molecular similarity are the tools of drug discovery.4

Some repurposed human drugs.

| Drug name | Original indication | New indication | New indication for rare diseases | Repurposed approach used |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minoxidil | Hypertension | Hair loss | Identification of hair growth as a secondary side effect | |

| Sildenafil | Angina | Erectile function | Identification as secondary effect | |

| Raloxifene | Osteoporosis | Breast Cancer | Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia (HHT) | Retrospective clinical analysis in breast cancer/Basic research in HHT |

| Propranolol | Cardiac disorders | Infantile Hemangioma (IH) | von Hippel Lindau disease (VHL) | Initial repurposing by chance in IH/Basic Research in VHL) |

| Ketokonazole | Fungal Infections | Cushing syndrome | Pharmacological analysis | |

| Aspirin | Analgesia | Colorectal Cancer | Retrospective clinical and pharmacological analysis | |

| Valproic acid | Epilepsy | Wolfram syndrome | Basic Research | |

| Losartan | Hypertension | Epidermolysis bullosa | Basic Research |

DRP is a particularly useful strategy for rare and neglected diseases, where the economic balance for drug investment is unfavorable. Regulatory agencies (EMA and FDA) have tried to encourage research into these disorders by tax waiving, fast-track approval, grants and fee waivers.2 Interestingly, some of the commercial barriers to drug repurposing, i.e. concerns regarding off-patent drugs, are not as important when addressing neglected conditions, since therapeutic research for such disorders are not driven by profit motivation. Actually, repurposing a low-cost off-patent drug, is ideal to assure patient accessibility.

Rare Diseases (RD) are conditions occurring in less than 5 in 10.000 people in EU, while in US, RD are those affecting to less than 200.000 people. Individually, RD are minoritary but not so rare to suffer. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), there are 5–8 thousand different RDs, affecting globally 400 million people, while less than 5% have an effective treatment. Drugs to treat RD are called Orphan drugs (OD). Most RD are life threatening with urgent demand for treatments. Pharmaceutical companies are not interested in RD research, since development costs of medicines for small numbers of patients may not be recovered. This explains the predominant role of academics and non-profit organizations in these conditions. Two strategies for searching OD may be considered, one is looking for new medicines, new treatments based on gene therapies, or combined gene-cell therapies. Traditional drug development, from the test tube to the patient takes around 10-15 years, and the cost rises to more than €1 billion. To reach clinical phases can take 6–8 years, and only 1 in 10,000 drug candidates will be successful. On the other hand, DRP is specially useful in RD, as a quick and less expensive alternative with an added value of the immediate use in clinical trials since safety is known from the first indication. Currently, about 20% of the ODs are repurposed.5,6

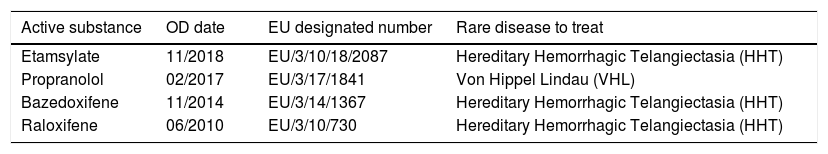

The choice of candidate drugs for a disease depends on the condition knowledge which helps to target the involved pathways/molecules. Our experience on RD for the last 20 years led to 4 repurposing OD designations, 3 for Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia (HHT) and 1 for von Hippel Lindau disease (VHL) (Table 2). Part of the increasing success of repurposing is due to the growing research information allowing to match disease targets with specific drugs.5 Moreover, advances in RD knowledge may be also translated to more prevalent conditions in medicine.

Orphan designations (OD) sponsored by CSIC in Rare Diseases.

| Active substance | OD date | EU designated number | Rare disease to treat |

|---|---|---|---|

| Etamsylate | 11/2018 | EU/3/10/18/2087 | Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia (HHT) |

| Propranolol | 02/2017 | EU/3/17/1841 | Von Hippel Lindau (VHL) |

| Bazedoxifene | 11/2014 | EU/3/14/1367 | Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia (HHT) |

| Raloxifene | 06/2010 | EU/3/10/730 | Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia (HHT) |

In the process of OD repurposing the following points are crucial: (i) Deciphering the gene(s) involved in the origin of the disease and pathogenic mechanism. (ii) Availability of models to replicate the disease: in vitro cell and animal models, as personalized as possible. (iii) Once the OD designation is warranted, the main challenge is to reach the patients, through the OD designation development. EMA regulatory measures try to encourage this process,6 however the sponsors (mainly academics and patients associations) need a link to specialized companies for OD commercial development. In the same way, DRP for more common diseases have to go through clinical phases before commercialization.

Propranolol repurposed for Infantile Hemangioma and von Hippel Lindau diseaseSpanish CSIC stands on a privileged position to conduct DRPs due to its multidisciplinary character as research institution. Remarkably, from 22 Spanish promoters who got 40 OD designations, CSIC has sponsored 4 RPDs in 2 different RD (Table 2).7 Personalized cultures specific for 2 different diseases were used in our CSIC group as in vitro strategy (Fig. 2).

Propranolol was approved in 1964 as a β-receptor antagonist with therapeutic properties in cardiac disorders.8

In 2008 Léauté-Labrèze discovered the therapeutic properties of propranolol for Infantile Hemangioma (IH) in a newborn suffering from a cardiac disorder and IH, a benign vascular tumor, present in a 4-5% of neonates, normally affecting face and limbs. Without spontaneous remission, surgery was the only treatment before the advent of propranolol. Based on propranolol therapeutic properties in 11 cases of IH,9 and after several case reports and successful trials, Hemangiol (an oral liquid presentation of propranolol) was approved for IH by EMA in 2014.10

Inspired by the work of Leauté-Labrèze,9 our lab has shown in vitro antiangiogenic and proapoptotic properties of propranolol in VHL, an autosomal dominant inherited RD (1:36,000 births)11 whose patients are heterozygous for mutations in the VHL tumor suppressor gene. The VHL protein targets HIF-1 for proteasomal degradation under normoxic conditions. Nevertheless, VHL mutation or loss of the second allele leads to a null-non-functional protein.12 In this situation, HIF-1 is not degraded and translocates to the nucleus, triggering the hypoxia program active in tumoral processes. VHL tumors are mainly retinal -or CNS Hemangioblastomas.13

Surgery is the only therapeutic option and repeated surgeries decrease the patients’ quality of life, thus VHL patients need drugs halting tumor progression and delaying surgeries. Several trials for VHL have used common strategies in cancer chemotherapy: antiangiogenic molecules (bevacizumab) or protein tyrosine kinases inhibitors (sunitinib). However these have shown limited or no response in VHL.14

An alternative antiangiogenic strategy was used in our group with propranolol. Briefly, propranolol treatment of primary cultured hemangioblastoma cells decreased viability, increased apoptotic death, and downregulated HIF targets expression as VEGF.15

Furthermore, in a phase 3 (EudraCT: 2014-003671-30)16,17 7 VHL patients bearing multiple retinal HBs were treated with propranolol (120mg/day for 12 months), neither the size nor the number of HBs increased, two retinal exudates disappeared, and plasma levels of VEGF (direct HIF target) were reduced in the patients. These findings warranted propranolol OD designation by EMA for VHL (EU/3/17/1841). The designation of propranolol as an OD for the treatment of VHL is a remarkable fact.

Finally, outline that the majority of clinical trials with repurposed OD included a small sample size. Therefore, future larger, controlled clinical studies, or a proper collection of case reports specifically focused on RPD, ODs remain necessary.

Ethical considerationsNo ethical issues.

FundingMinecoSAF2017-83351R; MicinnPID2020-115371RB-I00.

Conflict of interestWe have taken into account the instructions, ethical responsibilities, complied with the requirements of authorship and declare no conflict of interest.