Aluminum phosphide (ALP) poisoning, commonly referred to as rice tablet poisoning, is among the deadliest forms of poisoning. Treatment for aluminum phosphide poisoning is limited to supportive care, as no specific antidote is currently available. Sevelamer is being repurposed as an antidote for phosphine gas poisoning. This study seeks to assess the impact of sevelamer treatment on patients’ outcomes and overall prognosis.

MethodThis single-blind trial was conducted on patients suffering from aluminum phosphide poisoning (Oct 2023–Dec 2024). Participants were split into two groups: the control group received standard treatment, while the intervention group received standard treatment plus 2.4 g sevelamer carbonate initially, followed by 800 mg tablets every 8 hours. Data were collected using a study-specific checklist covering demographics, clinical symptoms, lab findings, patient outcomes, hospital stay duration, disease history, and secondary complications.

ResultsThe control group comprised 19 males (63.3%) and 11 females (36.7%). The sevelamer group, 26 males (81.25%) and 6 females (18.75%). This study demonstrated that sevelamer decreased mortality rates (56.25% compared to 86.7%) and enhanced ejection fraction (from 35.8% to 47.5% post-treatment). On the first day, it significantly raised blood PH (7.13 vs 7.23) and PO2 levels (34 vs 53.67).

ConclusionThis study suggests that sevelamer may serve as an effective antidote for treating aluminum phosphide poisoning. Further research is necessary to confirm its efficacy, determine optimal dosing strategies, and assess potential side effects in clinical settings.

La intoxicación por fosfuro de aluminio (ALP), comúnmente conocida como intoxicación por pastillas de arroz, es una de las formas de envenenamiento más letales. El tratamiento se limita a cuidados de soporte, ya que actualmente no existe un antídoto específico. El sevelamer se está readaptando como antídoto para la intoxicación por gas fosfina. Este estudio busca evaluar el impacto del tratamiento con sevelamer en el desenlace clínico y el pronóstico general de los pacientes.

MétodosEste ensayo simple ciego se llevó a cabo en pacientes que sufrieron intoxicación por fosfuro de aluminio (octubre de 2023–diciembre de 2024). Los participantes se dividieron en dos grupos: el grupo de control recibió el tratamiento estándar, mientras que el grupo de intervención recibió el tratamiento estándar más 2,4 g de carbonato de sevelamer inicialmente, seguido de comprimidos de 800 mg cada 8 horas. Los datos se recopilaron mediante una lista de verificación específica del estudio que cubría datos demográficos, síntomas clínicos, hallazgos de laboratorio, desenlace de los pacientes, duración de la estancia hospitalaria, antecedentes médicos y complicaciones secundarias.

ResultadosEl grupo de control estuvo compuesto por 19 hombres (63,3 %) y 11 mujeres (36,7 %). El grupo de sevelamer, por 26 hombres (81,25 %) y 6 mujeres (18,75 %). Este estudio demostró que el sevelamer disminuyó las tasas de mortalidad (56,25 % en comparación con 86,7 %) y mejoró la fracción de eyección (del 35,8 % al 47,5 % postratamiento). El primer día, elevó significativamente los niveles de pH sanguíneo (7,13 frente a 7,23) y de PO₂ (34 frente a 53,67).

ConclusiónEste estudio sugiere que el sevelamer podría actuar como un antídoto eficaz para el tratamiento de la intoxicación por fosfuro de aluminio. Se necesitan más investigaciones para confirmar su eficacia, determinar estrategias de dosificación óptimas y evaluar los potenciales efectos secundarios en entornos clínicos.

Aluminum phosphide (AlP), often referred to as the "rice pill" in Iran, is an extremely dangerous pesticide widely utilized to protect rice and other grains in storage facilities and during transit. This pesticide is extensively used in many developing countries.1–3 This pill's toxicity arises from the release of phosphine gas when exposed to moisture in the air, water, or hydrochloric acid in the stomach. The primary exposure routes are oral and respiratory.2,4 Poisoning typically presents symptoms rapidly, with the majority of fatalities resulting from cardiovascular complications. Fatalities occurring beyond 24 hours are generally linked to liver failure.5

A meta-analysis reveals that the mortality rate for ALP poisoning is approximately 27%, with men exhibiting a higher fatality rate than women. Younger individuals tend to experience better outcomes. Severe hypotension and cardiac toxicity are the most critical complications of this poisoning and are strongly linked to a high mortality rate.6 The mortality rate from AlP poisoning varies between 37% and 100%, with a fatal dose for an adult ranging from 0.15 to 0.5 grams.7,8 Reports of self-poisoning using aluminum phosphide tablets have risen in Iran in recent years.9

The primary clinical feature is cardiogenic shock, resulting from the direct myocardial toxicity of phosphine gas and pronounced metabolic acidosis.10–12 To minimize toxin absorption and increase blood pH, several interventions are recommended to prevent or mitigate metabolic acidosis.13,14 Addressing metabolic acidosis could enhance the patient's overall health.15 Laboratory findings linked to AlP poisoning include leukopenia, leukocytosis, hyperglycemia, elevated creatinine and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels, increased serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (SGOT) and serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase (SGPT) levels, metabolic acidosis, as well as abnormalities in serum potassium and magnesium electrolytes.16

The treatment for AlP poisoning is primarily supportive, as there is no specific antidote available. Various agents have been explored and tested in both experimental and clinical studies. Magnesium sulfate (MgSO4), known for its antioxidant properties and role as a cell membrane stabilizer, has been widely used as a therapeutic option in AlP poisoning. However, its efficacy remains debated.17 Potential agents for AlP poisoning include melatonin, coconut oil, N-acetylcysteine, sodium selenite, vitamins C and E, triiodothyronine, liothyronine, vasopressin, milrinone, Laurus nobilis L., 6-aminonicotinamide, boric acid, and acetyl-L-carnitine.18–20

Sevelamer (SVLM) is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of hyperphosphatemia in patients with chronic kidney disease or end-stage renal disease. SVLM is a polymeric drug composed of polyallylamine hydrochloride cross-linked with epichlorohydrin. It contains amine and ammonium-free groups that interact with phosphate groups through ion exchange and hydrogen bonding.21,22 An in vivo study demonstrated that sevelamer may serve as an effective antidote for treating aluminum phosphide poisoning, with a proposed mechanism explaining its interaction with phosphine gas.23

The growing use of agricultural poisons, such as rice tablets, has led to a rise in poisoning cases reported at medical centers. Its accessibility contributes to its use in suicide attempts. Consequently, this study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of sevelamer treatment on patients’ outcomes and prognosis.

Methods & materialsThis is a single-blind clinical trial conducted on patients poisoned by aluminum phosphide, referred to Loghman Hakim Hospital from October 2023 to December 2024. The study included patients aged 18 to 60 who presented to the hospital emergency department within 24 hours of ingesting aluminum phosphide. Eligibility criteria, besides the specified age range, required details of aluminum phosphide ingestion, symptoms indicative of poisoning, and a positive silver nitrate test (two patients who did not have a positive silver nitrate test were included in the study based on their symptoms and supporting environmental evidence, such as pill bottles and statements from companions).

Patients were excluded if they had a glomerular filtration rate below 30, a history of kidney or liver failure, acute myocardial infarction, congenital heart disease, heart failure, pregnancy or lactation, or if they arrived at the hospital more than 24 hours after consuming rice tablets. The exclusion criterion was the patient's decision to withdraw from the study.

Participants were divided into two groups: the control group received standard treatment, while the intervention group (SVLM) received standard treatment along with an initial dose of 2.4 grams of sevelamer carbonate (in sachet form, mixed with water or food) as prescribed by a specialist pharmacotherapy, followed by two 800 mg sevelamer carbonate tablets every 8 hours. These treatments continued until the patient either recovered or passed away (Fig. 1). Sevelamer, sourced from Mylan Pharmaceuticals, was obtained as 800 mg film-coated tablets with the ATC code V03AE02. According to the pharmacotherapist’s opinion and the details provided in the electronic medicines compendium, the recommended initial loading dose was determined to be 2.4 g.

Patients were randomized using the Random Number Generator version 1.4, which assigned a number between 1 and 62. This study employed that patients were assigned to groups based on their numbers: even numbers placed them in the control group, while odd numbers placed them in the intervention group. The group allocation depended on whether the patient's number was even or odd. In this study, patients were unaware of their drug assignment; they did not know whether they were receiving the study drug (SVLM) alongside standard treatment or only the standard treatment. The nurses administering the medication were involved in the study's design, and they were not informed about the specific interventions or study objectives. However, the participating physicians, including internal medicine residents and specialists in internal medicine, toxicology, and cardiology, were fully aware of these details.

A checklist specifically designed for this study was used to collect data. The checklist encompassed demographic details (such as age and gender), clinical symptoms including vital signs (heart rate and blood pressure were measured every day; ejection fraction was measured before and after treatment), laboratory findings (PH, PCO2, bicarbonate, and PO2 were measured every day), patient outcomes (recovery or death), length of hospital stay, history of diseases and secondary complications in patients.

The sampling process was completed using a convenient non-probability sampling method. The sample size was calculated based on a 95% confidence interval, a type I error (α = 0.05), a type II error (β = 0.2), and a statistical power of 80%, while accounting for a 20% likelihood of sample exclusion. Ultimately, a total of 62 participants were selected, with 32 assigned to the sevelamer treatment group and 30 to the control group.

Statistical analysisThe data were described using mean, standard deviation, median, range, frequency, and percentage. To compare the outcomes between the two groups based on the variable under examination and to assess data normality (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test), statistical tests such as the t-test, chi-square test, or Fisher's exact test were applied. Repeated measures ANOVA and Tukey's post-test were applied to analyze within-group data across various treatment days. All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 26.0 statistical software. A significance level of P≤0.05 was predetermined for all statistical tests to identify statistically significant differences. The effect size was calculated based on partial Eta squared with a repeated measures ANOVA test. An odds ratio (OR) was calculated with a 95% confidence interval (CI).

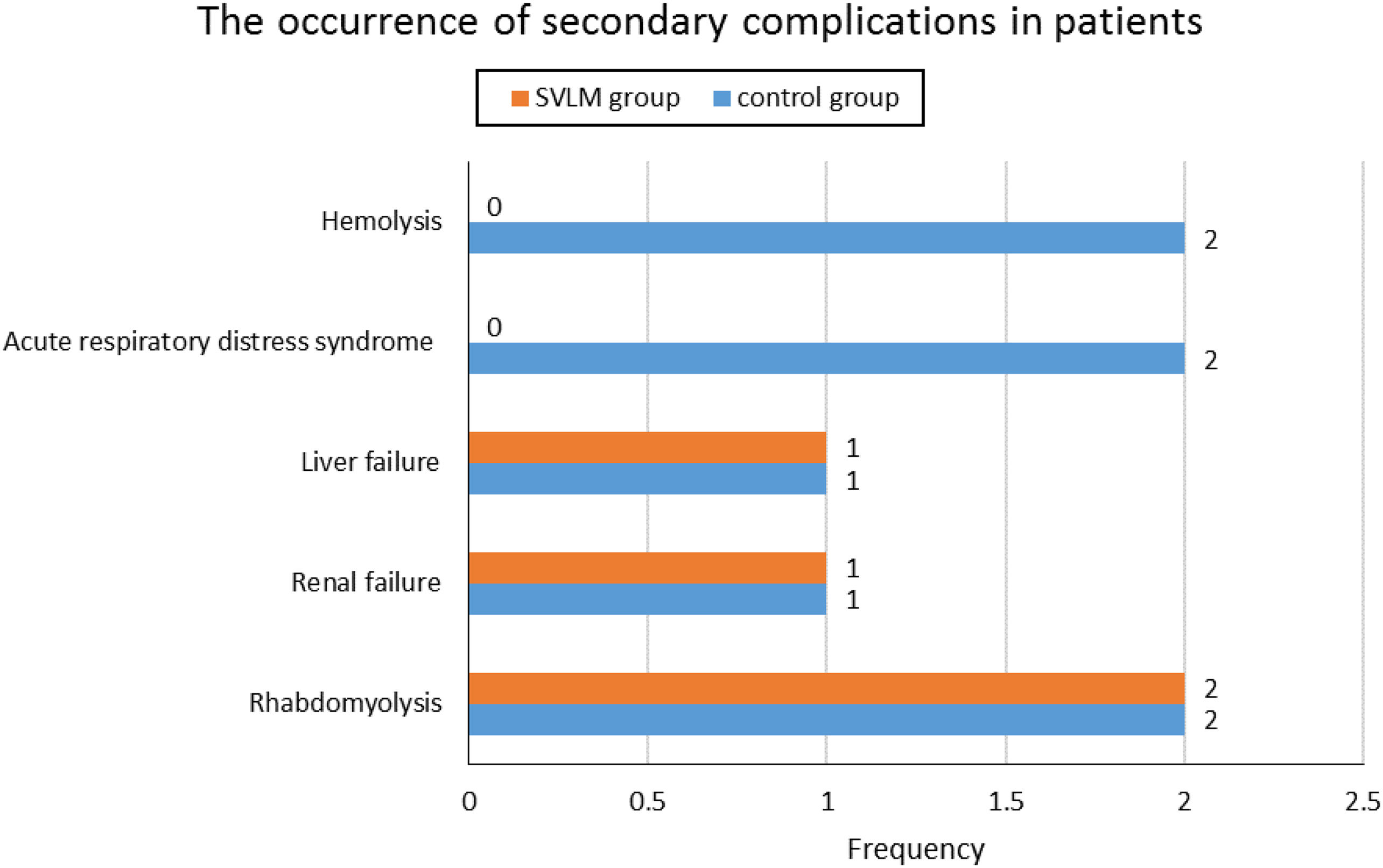

ResultsA total of 62 patients participated in this study, with 30 in the control group and 32 in the SVLM treatment group. Table 1 shows the initial patient information before starting treatment. Out of a total of 45 males, 26 (81.25%) were in the SVLM group, while the rest were in the control group. Among 17 females, 6 (18.75%) were in the SVLM group, with the remainder in the control group. The average age in the control group was 35.43±13.61 years, while in the SVLM group, it was 36.69±11.16 years. All studied patients had intentional use and suicidal intent. All patients had ingested aluminum phosphide orally.

The initial information of patients and mortality rate in two groups.

| Control group | SVLM group | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 19 (63.3%) | 26 (81.25) | 0.157 |

| Female | 11 (36.7%) | 6 (18.75%) | ||

| Age (year) | 35.43±13.61 | 36.69±11.16 | 0.692 | |

| GCS | 9.23±5.27 | 10.31±4.62 | 0.396 | |

| The silver nitrate test | Yes | 29 (96.7%) | 31 (96.9%) | 1 |

| NO | 1 (3.3%) | 1 (3.1%) | ||

| Nausea | Yes | 22 (73.3%) | 27 (84.4%) | 0.357 |

| No | 8 (26.7%) | 5 (15.6%) | ||

| The body temperature (C°) | 36.6±0.4 | 36.8±0.42 | 0.46 | |

| Duration of hospitalization (hr) | 40.53±54.37 | 33.29±34.21 | 0.543 | |

| Duration of intubation (hr) | 38.93±55.21 | 76±263.65 | 0.464 | |

| Dead | 26 (86.7%) | 18 (56.25%) | 0.039⁎ | |

Numbers are listed as frequency (percentage) or mean±SD.

The silver nitrate test was positive in 96.7% (29 people) of the control group and in 96.6% (31 people) of the SVLM group. None of the patients had kidney failure, liver failure, an acute heart attack, or a history of heart failure. Nausea was present in 73.3% (n=22) of the control group and 84.4% (n=27) of the SVLM group. The average Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) in the control group was 9.23±5.27, while in the SVLM group, it was 10.31±4.62. The average body temperature recorded was 36.6°C in the control group and 36.8°C in the SVLM group (Table 1). The respiratory rate averaged 10.03±8.8 in the control group and 13.81±8.3 in the SVLM group. Comparison of ejection fraction (EF) revealed no significant difference between the two groups after treatment (control group=43.33%, SVLM group=47.55%, P=0.505). However, intra-group analysis using a paired t-test showed a significant difference (P=0.004) in the group receiving SVLM before and after treatment, with EF increasing post-treatment (35.8% vs 47.5%). No such difference was observed in the control group (Fig. 2).

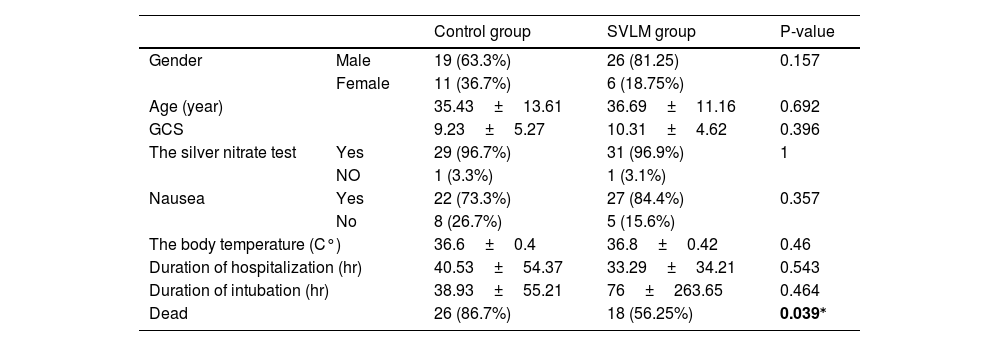

Heart rate (HR) measurements taken at hospital admission and during treatment days revealed no significant differences between the two groups (At entry: P=0.461; Day 1: P=0.069; Day 2: P=0.497; Day 3: P=0.255). Similarly, no significant differences were found in the within-group comparison (Table 2). Systolic blood pressure (SBP) measurements taken upon hospital admission and during treatment days revealed a significant difference between the two groups (admission: P = 0.045; day 1: P = 0.029; day 2: P = 0.014; day 3: P = 0.006). The SVLM group exhibited higher systolic blood pressure. However, comparisons within the SVLM group across different days did not show any significant differences, indicating that the higher systolic blood pressure in this group was likely coincidental from the outset and not specifically influenced by SVLM (Table 2). Diastolic blood pressure (DBP) measurements recorded at hospital admission and throughout the treatment days showed no significant differences between the two groups (admission: P = 0.181; day 1: P = 0.218; day 2: P = 0.695; day 3: P = 0.183). Likewise, no significant differences were found in the within-group comparisons (Table 2).

Comparison of systolic and diastolic blood pressure and heart rate between groups on different treatment days.

| Heart Rate (HR) pulse/min | Diastolic blood pressure (DBP) mmHg | Systolic blood pressure (SBP) mmHg | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control group | SVLM group | P-value | Control group | SVLM group | P-value | Control group | SVLM group | P-value | |

| At entry | 94.07±29.08 | 98.91±21.36 | 0.461 | 44.60±27.23 | 53.41±23.76 | 0.181 | 75.07 | 89.84 | 0.045⁎ |

| Day 1 | 88.40±26.38 | 99.56±20.5 | 0.069 | 30.87±25.46 | 40.19±31.23 | 0.218 | 73.63 | 85.72 | 0.029⁎ |

| Day2 | 97.64±19.03 | 93.08±14.6 | 0.497 | 37.29±26.18 | 42.27±34.38 | 0.695 | 84.64 | 101.25 | 0.014⁎ |

| Day3 | 101.25±20.93 | 91.10±12.95 | 0.255 | 33.75±30.68 | 54.89±31.69 | 0.183 | 86.88 | 110.33 | 0.006⁎⁎ |

Numbers are listed as mean±SD.

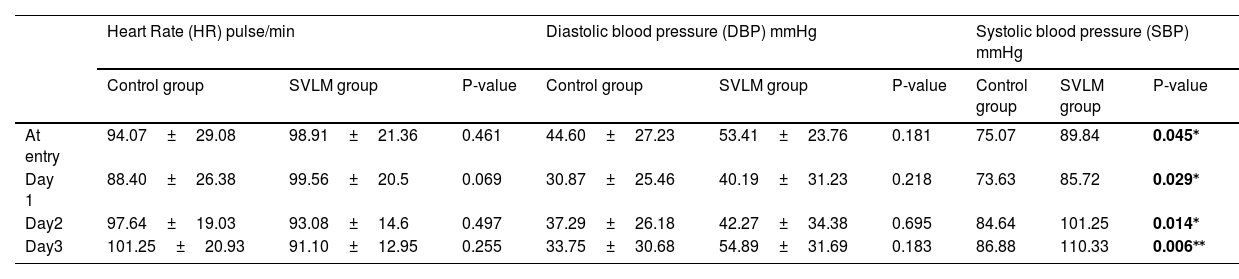

The blood PH analysis in the two groups revealed that on the first day of treatment, the pH was significantly lower in the control group (p=0.045); however, no significant differences were noted in the following days (Table 3). The blood bicarbonate (HCO3) level analysis in the two groups revealed no significant differences on treatment days (day 1: P = 0.423; day 2: P = 0.788; day 3: P = 0.740) (Table 3). Analysis of the partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PCO2) levels between the two groups showed no significant differences across the treatment days (day 1: P = 0.065, day 2: P = 0.521, day 3: P = 0.474) (Table 3). On the first day of treatment, the analysis of partial pressure oxygen (PO2) showed a significantly higher PO2 in the control group (P=0.023); however, no significant differences were observed on subsequent days (Table 3).

Comparison of the blood gases between groups on different treatment days.

| At entry | Day 1 | Day2 | Day3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PH | Control group | 7.22±0.19 | 7.13±0.21 | 7.21±0.21 | 7.34±0.83 |

| SVLM group | 7.30±0.13 | 7.23±0.16 | 7.23±0.26 | 7.38±0.12 | |

| P-value | 0.067 | 0.045⁎ | 0.779 | 0.388 | |

| The blood bicarbonate (HCO3) mEq/L | Control group | 17.09±5.3 | 16.92±5.3 | 21.72±7.5 | 28.2±4.8 |

| SVLM group | 17.27±6.4 | 16.97±4.8 | 21.02±7.1 | 27.49±4.1 | |

| P-value | 0.912 | 0.423 | 0.788 | 0.740 | |

| The partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PCO2) mmHg | Control group | 39.41±13.9 | 46.75±10.2 | 50.4±11.6 | 49.61±8.1 |

| SVLM group | 34.41±13.7 | 41.87±10.2 | 47.5±11.8 | 46.11±12.1 | |

| P-value | 0.185 | 0.065 | 0.521 | 0.474 | |

| The partial pressure oxygen (PO2) mmHg | Control group | 40±26.7 | 34±15.3 | 52.61±15.9 | 46.04±12.04 |

| SVLM group | 49.96±27.6 | 53.67±28.4 | 46.04±12.04 | 48.85±12.2 | |

| P-value | 0.180 | 0.023⁎ | 0.352 | 0.624 | |

Numbers are listed as mean±SD.

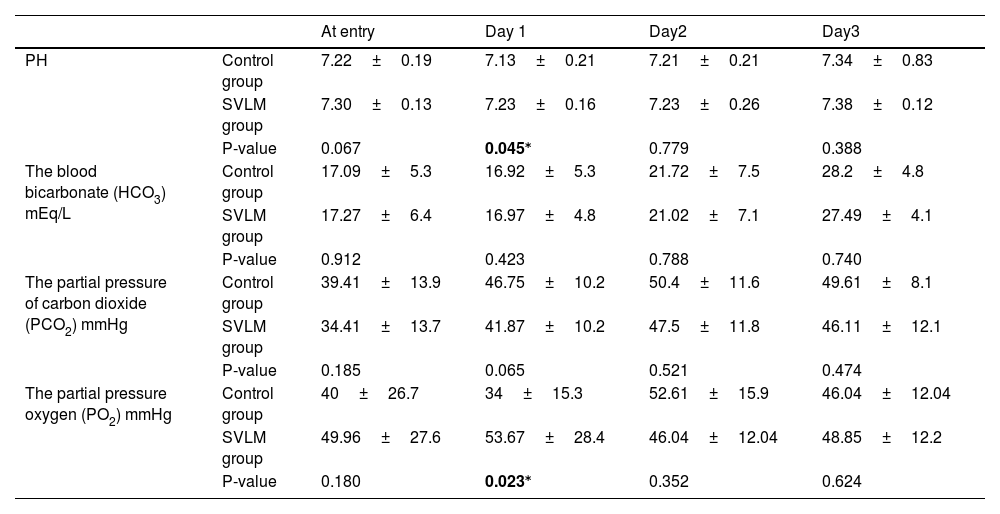

The mortality rate in the control group was 86.7%, while in the SVLM group, it was significantly lower at 56.25% (p=0.039). The occurrence of secondary complications in patients, including rhabdomyolysis, renal failure, liver failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and hemolysis, showed no significant differences between the two groups (Fig. 3). The average hospital stay duration was 40.53±54.4 hours in the control group and 33.29±34.2 hours in the SVLM group, with no significant difference observed (P=0.543). The effect size was 0.415. The odds ratio value of 0.125 was calculated (CI95%: -0.935 to 1.186).

Discussion and conclusionAlP, commonly known as rice tablet poisoning, is one of the most dangerous conditions, leading to a significantly high mortality rate. As a result, prompt emergency management is crucial in such cases. However, various instances of this poisoning have been reported in urban areas, with many patients sustaining untreated injuries during transportation to specialized toxicological centers.24 The absence of a definitive antidote further complicates the immediate treatment of these cases. The alarmingly high mortality rate from this poisoning in Asia is deeply concerning.25 Researchers are actively exploring and testing different treatment approaches to help reduce fatalities. This study showed that SVLM reduced mortality rates and improved EF. On the first day, it effectively increased blood PH and PO2 levels.

Our study demonstrated that sevelamer significantly lowers mortality in poisoned patients compared to the control group (86.7% vs 56.25%). Heidari and colleagues previously demonstrated that sevelamer enhances survival rates in male Sprague Dawley rats exposed to aluminum phosphide poisoning.23 The findings of our study, consistent with their results, validate the impact of sevelamer administration on enhancing survival rates.

Zaghary et al. recently highlighted the critical role of ejection fraction in predicting mortality and complications associated with acute AlP toxicity. Their findings revealed that an ejection fraction below 37.5% demonstrated a 96.8% accuracy rate, with outstanding mortality discrimination, 100% sensitivity, 93.2% specificity, a positive predictive value of 89.6%, and a negative predictive value of 100%.26 Our research revealed a significant increase in EF within the group treated with SVLM. As noted in the Zaghary study, this improvement may explain the reduced mortality rate observed in the SVLM group.

According to the Sagah study, blood PH, HCO3, and PO2 may serve as indicators for predicting mortality in ALP-poisoned patients, with blood PH and PO2 potentially guiding the necessity for mechanical ventilation.27 Our study demonstrated that SVLM significantly elevated PH and PO2 levels exclusively on the first day of administration. Considering the critical role of prompt treatment for blood gas disorders in ensuring survival, this notable early improvement observed in the SVLM group holds significant importance.

Finally, SVLM, a form of nanomedicine, is used to manage phosphatemia. This polymer-based drug can be administered to treat AlP-induced toxicity in patients. Sevelamer lowered mortality rates and enhanced ejection fraction (EF), a key prognostic indicator. Initially, it was effective in raising blood PH and PO2. While further research with larger sample sizes and varying doses of sevelamer is advised, this study suggests that sevelamer may serve as an effective antidote for treating aluminum phosphide poisoning.

LimitationThis study was carried out at a single poison center. A multicenter study could offer more comprehensive data for generalizing the findings. Additionally, carrying out a study with a larger sample size would yield more reliable information.

Authors’ contributionsAll authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Availability of data and materialThe data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Consent for publicationNot applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participateThis study was conducted by the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences (code IR.SBMU.RETECH.REC.1402.712). We had no participants under the age of 18. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and for cases where patients had a severely reduced level of consciousness, informed consent was obtained from their legal guardian or an appropriate representative of these participants on their behalf.

FundingThe authors declared that this study received no financial support.

None.

The authors would like to thank the Toxicological Research Center (TRC) of Loghman Hakim Hospital, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran, for their support, cooperation and assistance throughout the period of study.