Sarcoidosis is a systemic inflammatory disease characterized by non-caseating granulomas. Thoracic involvement is the most common site of the disease, observed in approximately 90% of cases. Extra-thoracic involvement occurs in 50%, but bone involvement remains rare (3–13%). There is no codified therapeutic management.

Case 1: A 30-year-old woman presented with dyspnea and fever. Imaging revealed mediastinal adenomegaly and a lytic femoral neck lesion. Biopsies confirmed granulomatous disease, leading to a diagnóstico of type 2 medullary-pulmonary sarcoidosis with bone involvement. She was treated with corticosteroids and required surgical intervention due to a fracture risk.

Case 2: A 57-year-old woman with systemic sarcoidosis experienced relapse after corticosteroid treatment, presenting with new osteolytic lesions and lymphadenopathy. Biopsy confirmed osseous sarcoidosis. High-dose corticosteroids, combined with methotrexate, led to significant clinical improvement and stabilization of lytic lesions on imaging.

Skeletal lesions are rare and can mimic malignancies. Diagnosis requires histological confirmation. Treatment primarily involves corticosteroids, and it may necessitate further immunosuppressive strategies.

La sarcoidosis es una enfermedad inflamatoria sistémica caracterizada por granulomas no caseificantes. La afectación torácica es la localización preferente, observada en el 90% de los casos. La afectación extratorácica ocurre en el 50%, pero la afectación ósea sigue siendo rara (3–13%). No existe un tratamiento codificado.

Caso 1: Mujer de 30 años que consultó por disnea y fiebre. Las imágenes revelaron adenomegalias mediastínicas y una lesión lítica en el cuello femoral. Las biopsias confirmaron una enfermedad granulomatosa, lo que permitió diagnosticar una sarcoidosis medular-pulmonar tipo 2 con afectación ósea. Fue tratada con corticoides y requirió intervención quirúrgica por riesgo de fractura.

Caso 2: Mujer de 57 años con sarcoidosis sistémica que presentó recaída tras tratamiento con corticoides, con aparición de nuevas lesiones osteolíticas y adenopatías. La biopsia confirmó la sarcoidosis ósea. El tratamiento con corticoides a dosis altas asociado a metotrexato condujo a una mejoría clínica significativa y estabilización de las lesiones líticas en las imágenes.

Las lesiones óseas son raras y pueden simular neoplasias. El diagnóstico requiere confirmación histológica. El tratamiento se basa principalmente en corticoides, y puede requerir estrategias inmunosupresoras adicionales.

Sarcoidosis is a systemic inflammatory disease characterized by the formation of epithelioid and gigantocellular granulomas without caseous necrosis. Its pathophysiology remains poorly understood.1 Thoracic involvement is the most common site of the disease, observed in approximately 90% of cases. Extra-thoracic sites are present in 50% of cases and are primarily located in lymph nodes, the ophthalmic region, skin, and liver.2

Bone involvement in sarcoidosis remains uncommon, affecting between 3% and 13% of patients depending on the study.2,3 It affects the bones of the extremities and, more rarely, the skull and vertebrae. Therapeutic management has not yet been codified.

Case 1:

A 30-year-old woman presented with asthenia and NYHA class III dyspnea. Physical examination revealed fever (38.6 °C), bibasilar crackles, hepatomegaly, and no peripheral lymphadenopathy.

Laboratory investigations showed lymphopenia (1000/μL), mild inflammation, as indicated by an elevated ESR (30 mm/1 h) and CRP (24 mg/L), along with a mild polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia (13.5 g/L). Liver function tests were within normal limits, except for a slightly elevated alkaline phosphatase (144 UI/L), while AST and ALT were normal.

A chest X-ray showed bilateral interstitial syndrome. A thoracic-abdominal-pelvic CT scan showed mediastinal adenomegaly associated with pulmonary nodules and a Lodwick IB geographic-pattern lytic lesion in the femoral neck measured at 40 UH.

MRI of the pelvis showed non-specific elongated oval signal abnormalities in the long axis of the femoral neck.

For infectious causes, tuberculosis was a primary concern given the lymphadenopathy and pulmonary involvement. Tuberculin skin testing revealed complete anergy. The BK test in sputum and the Quantiferon test were negative.

Neoplastic causes required extensive evaluation. Bilateral mammography for metastatic carcinoma returned as BI-RADS category 2, indicating no abnormalities. Upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed no mucosal lesions or masses. Thyroid ultrasound showed a normal gland without nodules. Tumor markers, including CA 15–3, CA 19–9, and carcinoembryonic antigen, were all within normal limits.

For multiple myeloma, serum protein electrophoresis showed no monoclonal gammopathy. Serum-free light chains showed a normal kappa-to-lambda ratio of 1.2. The 24-h urine protein electrophoresis demonstrated no Bence-Jones proteinuria.

To evaluate for lymphoma, positron emission tomography with CT using fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose was performed. This showed hypermetabolic activity in the mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes. There were no other suspicious lesions. The overall pattern was not typical for lymphoma, which usually presents with more extensive nodal disease.

Bronchoscopy showed no endobronchial lesions, but bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) revealed lymphocytic alveolitis and a CD4/CD8 ratio of 2.6. Biopsy of mediastinal adenopathy showed a ganglion parenchyma containing numerous small granulomas composed of epithelioid and giant cells without necrosis. Immunohistochemical studies (CD20, CD3, and cytokeratin) were negative. Salivary gland biopsy was consistent with granulomatous disease. An open bone biopsy was performed. Histological examination revealed a nonspecific chronic inflammatory process, with no evidence of malignancy or specific granulomas at this site.

The diagnóstico of radiological type 2 medullary-pulmonary sarcoidosis, without respiratory effects and with bone involvement, was maintained.

The patient received oral corticosteroids at 0.5 mg/kg/day for one month, followed by a weekly taper of 5 mg. Intramedullary nailing of the femoral neck was performed due to a significant fracture risk. No follow-up imaging since the patient became pregnant.

Case 2:

We present the case of a 57-year-old woman with systemic sarcoidosis, initially diagnosed based on cervical, mediastinal, and abdominal lymphadenopathy, along with pulmonary involvement manifesting as stage II dyspnea, dry cough, and bilateral parenchymal nodules and micronodules. Bronchoalveolar lavage revealed lymphocytic alveolitis with an elevated CD4/CD8 ratio of 3.03.

The cervical lymph node biopsy revealed granulomatous adenitis.

The patient was treated with oral corticosteroid therapy (0.5 mg/kg/day) followed by a weekly taper of 5 mg, which resulted in significant clinical and functional improvement.

Nine months after corticosteroid discontinuation, she experienced worsening dyspnea, aggravated axial arthralgia, and new-onset left-sided hyperhidrosis. Clinical examination revealed cervical and axillary lymphadenopathy without inflammatory signs, along with orthostatic hypotension.

Laboratory tests showed isolated elevated alkaline phosphatase (320 IU/L) and evidence of systemic inflammation (elevated CRP, accelerated ESR). Plasma protein electrophoresis (PPE) and electromyography (EMG) were unremarkable.

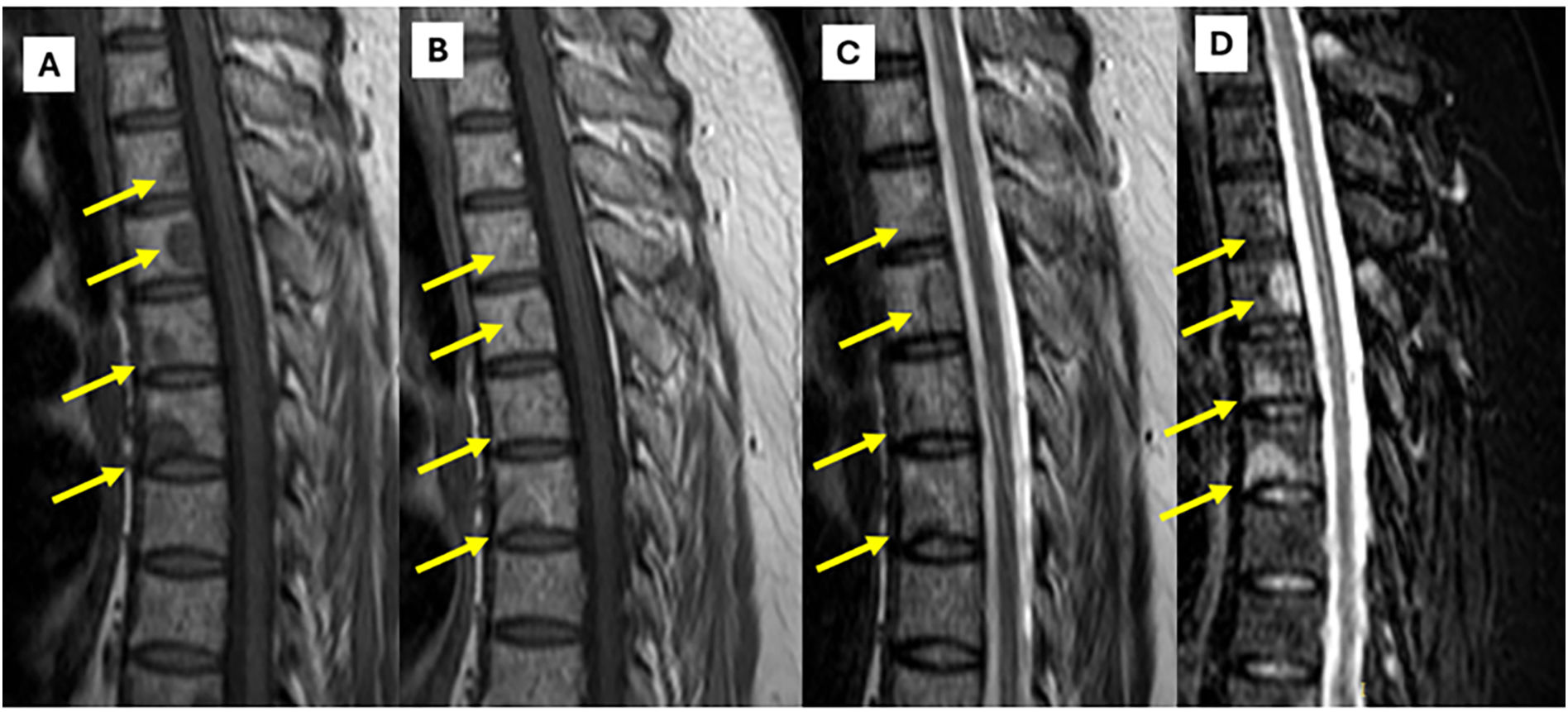

Contrast-enhanced thoraco-abdominal-pelvic computed tomography (CT) demonstrated stable lymphadenopathy and pulmonary lesions. However, it revealed multiple well-defined osteolytic lesions (Lodwick type Ib) involving cervical, thoracic, and lumbar vertebral bodies and posterior arches, the pubic symphysis, and the proximal femurs, with associated fatty marrow infiltration (Fig. 1).

MRI findings in thoracic spine sarcoidosis.

Panel A (T1-weighted image) demonstrates multiple bone lesions in the thoracic spine presenting with low signal intensity relative to the adjacent bone marrow. Panel B (T1-weighted image post-gadolinium injection) reveals heterogeneous enhancement of these lesions, indicative of their infiltrative granulomatous nature. Panel C (T2-weighted image) shows the same lesions with moderate hyperintensity, whereas Panel D (STIR sequence) accentuates their pronounced hyperintensity, facilitating improved detection and characterization of osseous involvement in sarcoidosis.

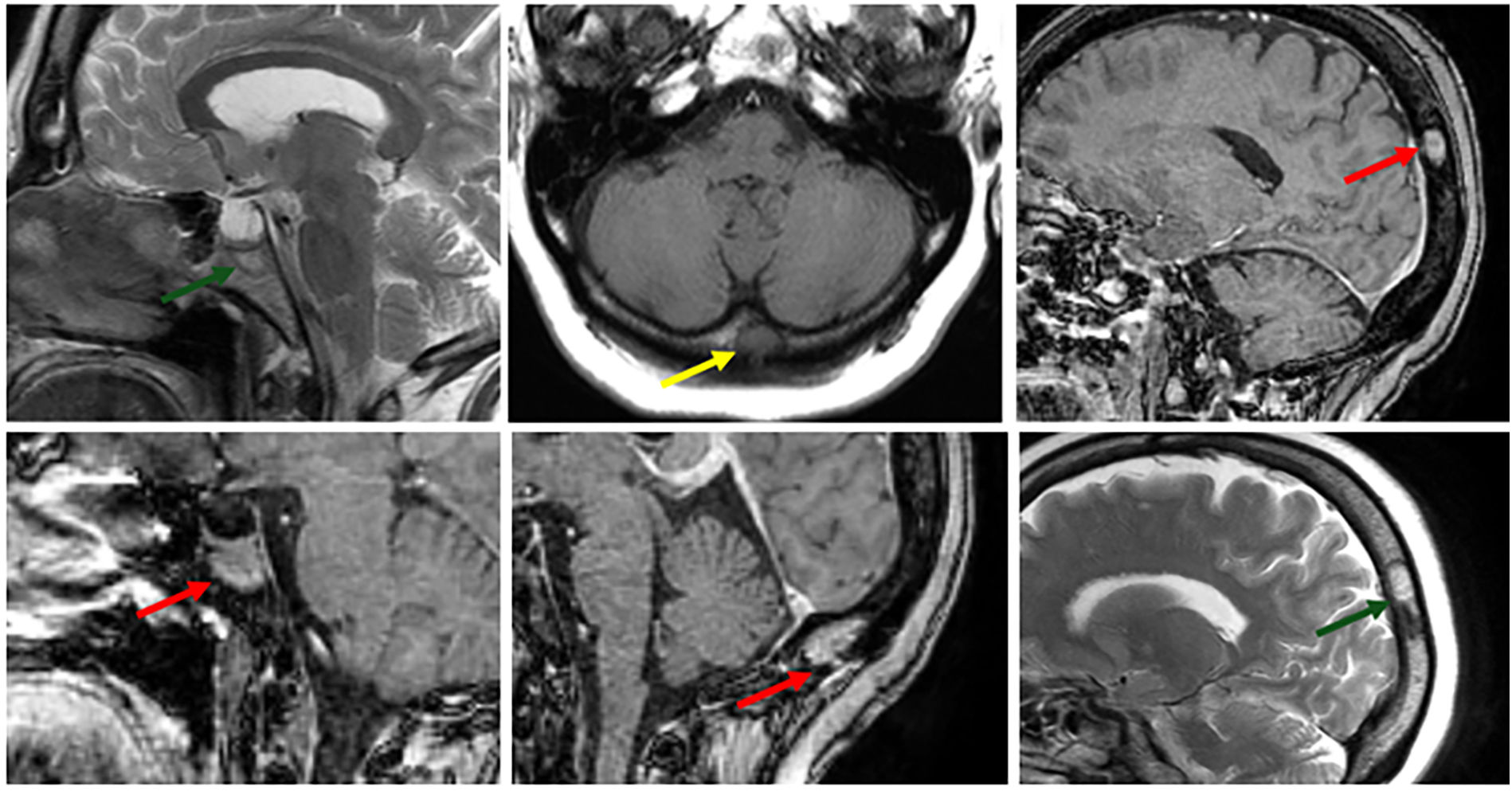

Brain and spinal MRI demonstrated diffuse nodular involvement of the cervical and axial spine, along with a few cranial lesions, as well as nodular T2/FLAIR hyperintensities in the subcortical and deep supratentorial white matter (Fig. 2). Diffuse, well-defined nodular bone marrow replacement lesions affecting the entire spine, involving the vertebral bodies and posterior arches. They are round and oval in shape, with low signal intensity on T1-weighted images, high signal intensity on STIR images, and intermediate signal intensity on T2-weighted images, showing enhancement after gadolinium injection.

MRI Characteristics of Skull Bone Lesions in Sarcoidosis.

Bone lesions in the skull are depicted as areas of low signal intensity on T1-weighted images (yellow arrow) and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images (green arrow). These lesions demonstrate heterogeneous enhancement following gadolinium administration (red arrow), consistent with granulomatous infiltration characteristic of sarcoidosis.

The BK testing in sputum and tuberculin skin testing were negative.

Serum protein electrophoresis demonstrated a normal pattern without a monoclonal peak. Serum immunofixation was negative for monoclonal protein.

A mammography revealed no abnormalities. Thyroid ultrasound revealed no nodules or masses.

Axillary lymph node biopsy confirmed non-necrotizing granulomatous adenitis. CT-guided bone biopsy revealed granulomatous remodeling of bone tissue without necrosis, consistent with osseous sarcoidosis. Bone scintigraphy did not show any suspicious hyperfixation foci.

High-dose corticosteroid therapy (1 mg/kg per day)was initiated for one month, followed by a weekly taper of 5 mg for a total duration of 9 months. Methotrexate treatment at a dose of 15 mg per week orally was initiated in combination with corticosteroid therapy from the outset. The progression was marked by clinical and biological improvement. Follow-up imaging showed stable lytic lesions. The follow-up period was 24 months.

DiscussionSarcoidosis is a systemic granulomatous disease of unknown etiology, characterized by the formation of non-caseating granulomas affecting various organs. Although pulmonary and lymphatic involvement are the most common manifestations, sarcoidosis-related bone lesions are also described, but with rare frequency. It is often asymptomatic but may mimic metastases, myeloma, or infections.3,4

Skeletal involvement is typically associated with disseminated forms of sarcoidosis and is estimated to occur in approximately 3% to 13% of cases.

As highlighted in our observations, the entire skeleton may be a site for the development of osseous sarcoidosis.

The hands are affected in approximately 15% of patients.3 Sarcoid dactylitis, also known as “sarcoid acromelic pseudo-polyarthritis,” mainly affects the second and third phalanges. Various presentations of bone lesions can be observed, including the apple core pattern,5 bone cysts in the phalangeal heads of the hands, and a “moth-eaten” pattern.

Involvement of the long bones (humerus, femur, tibia) is often presented as single or multiple lacunar lesions in the epiphysis. The cortex is thinned, sometimes with pathological fractures that do not elicit a periosteal reaction.

Clinically, vertebral involvement may manifest as mechanical or inflammatory dorsolumbar pain, sometimes with radiculalgia or spinal cord involvement if the lesion is extensive. Our second patient presented with pain of an inflammatory nature, without any notable neurological deficit, which emphasized the variability of presentations, making diagnóstico often delayed.

The radiological presentation of sarcoidosis-related bone lesions is polymorphous, characterized by well-defined osteolytic lacunae, often classified as type Ib according to Lodwick, and medullary infiltrations visible as T1 hypointensity and T2 hyperintensity on MRI.6 This type of lesion requires a rigorous differential diagnóstico, mainly including bone metastases, multiple myeloma, and granulomatous infections.3 In our two cases, the absence of signs of malignancy on further examination (PET scan, digestive tract examination, mammography) and histological confirmation by biopsy confirmed the sarcoidosis origin.

Histological confirmation is essential in cases of atypical bone involvement. In both cases, biopsy of mediastinal and/or axillary adenopathy, as well as bone biopsy, revealed characteristic non-caseating epithelioid granulomas without caseous necrosis, thus confirming the diagnóstico.7

There is no consensus for the treatment of bone sarcoidosis. It is not required for asymptomatic patients. However, as bone involvement often indicates multisystem disease, many patients will undergo therapy for other organ manifestations.8 Corticosteroids are the most commonly prescribed first-line drugs in symptomatic bone sarcoidosis.9,10 Both our patients received systemic corticosteroids at varying initial doses (0.5 to 1 mg/kg/day), resulting in significant clinical improvement. For the first patient, follow-up was limited due to pregnancy before control imaging could be obtained. In contrast, the second patient showed notable clinical improvement, along with a partial radiological response, on follow-up.

The addition of immunosuppressants (methotrexate, azathioprine) could be discussed in cases of chronic progression or dependence on corticosteroids.11

ConclusionBone involvement in sarcoidosis, although rare, should be systematically suspected in the presence of any osteolytic lacuna in a granulomatous context. A rigorous diagnostic approach and close monitoring are necessary to optimize therapeutic management and avoid relapses.

The skeletal manifestations of sarcoidosis present a significant diagnostic challenge due to their nonspecific presentation and similarity to those of malignant or infectious processes.

The diagnostic complexity of bone sarcoidosis is due to subtle early radiological changes and variable clinical progression. A thorough differential diagnóstico is essential to exclude malignancy and infection. Advanced imaging and histopathological analysis are fundamental for accurate diagnóstico.

Therapeutic management requires individualization based on symptom severity, the extent of bone involvement, and overall disease activity. While corticosteroids remain the first-line treatment, alternative immunosuppressive agents should be considered for refractory cases or to minimize long-term steroid complications.

Long-term surveillance is crucial given the unpredictable nature of sarcoidosis and the risk of complications such as pathological fractures. A multidisciplinary approach involving rheumatologists, pulmonologists, and orthopedic specialists ensures optimal patient outcomes and appropriate therapeutic adjustments based on the disease's progression.

Ethical considerationsThis article does not report on a study involving human participants or animals.

We declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to the content of this article.