Wilson's disease, an autosomal recessive genetic disorder, affects copper metabolism due to mutations in the ATP-7B gene. Excess copper accumulates in various tissues, leading to organ damage. It commonly affects children and adolescents, manifesting as liver damage and neuropsychiatric symptoms.1

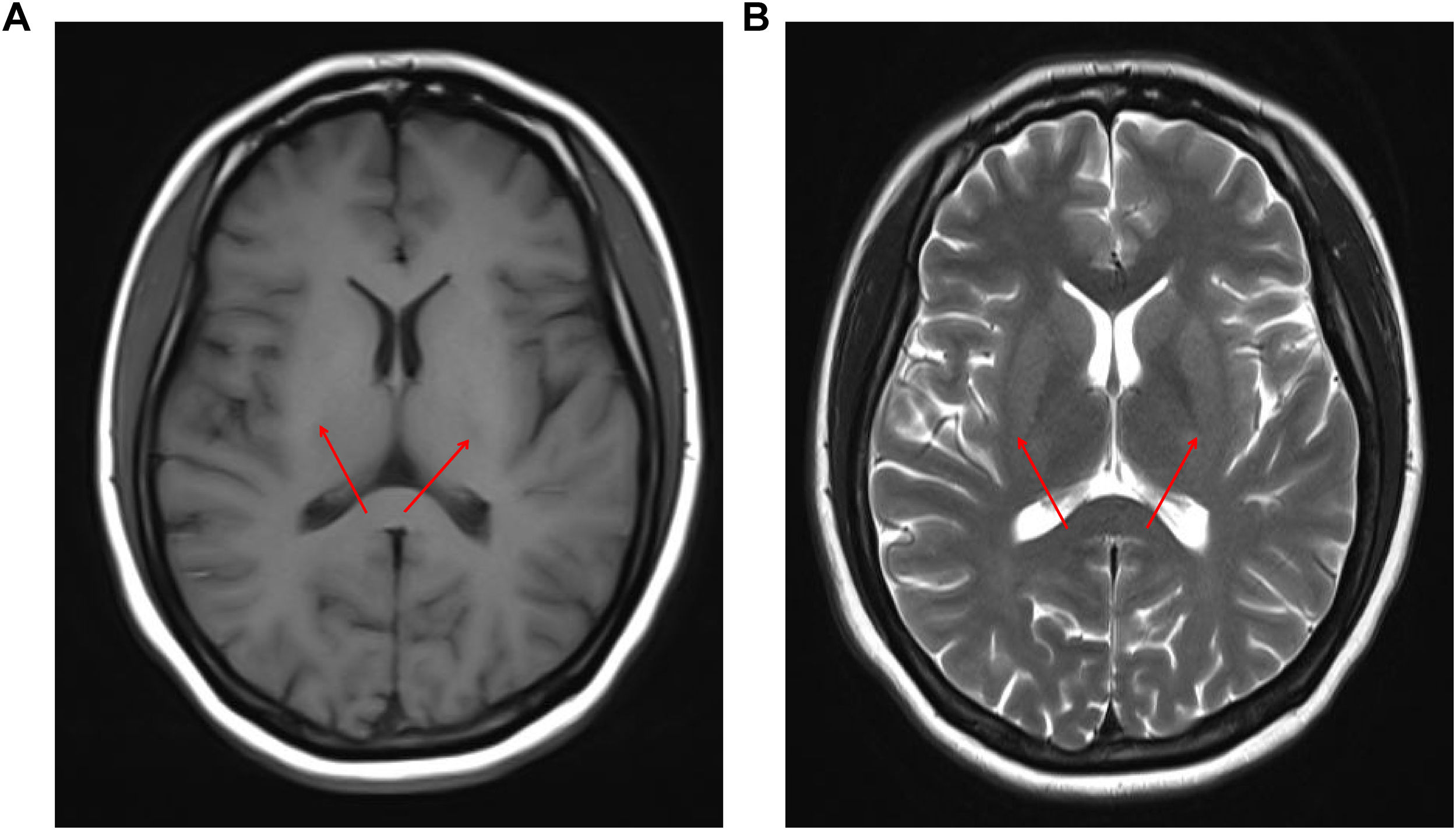

A 20-year-old Chinese female went to our hospital's Hematology Department with dark urine and fatigue. She had a history of menstrual disorders and depression. Physical exam showed jaundiced, acne skin, and leg edema. Laboratory tests revealed mild anemia, elevated reticulocyte count, hypoalbuminemia, hyperbilirubinemia, positive urine protein, and positive urobilinogen (Table S1). Kayser–Fleischer ring was not revealed with slit-lamp examination. Tests related to viral and autoimmune hepatitis were negative. The hormone levels and copper metabolism-related indicators are presented in Table 1. Abdominal ultrasound showed diffuse hepatic lesions, increased gallbladder with unsmooth and thickened wall. A Gynecologic ultrasound revealed a small uterus and an increased number of follicles in the right ovary. The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) suggested a symmetrical increase in signal in the bilateral bean nuclei (Fig. S1) and no occupying lesions in the pituitary region. Enhanced CT of the whole abdomen showed no definite abnormality. Flow cytometry and bone marrow aspiration morphological detection exclude paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, and malignant hematologic diseases. Detection of the ATP7B gene revealed 2 compound heterozygous mutations: c.2975C>T on exon 13 (p.Asp 1047Val) and c.2333G>T (p.Gly 943Asp) on exon 8.

Indicators of copper metabolism and hormone levels at baseline.

| Parameter | Value | Reference values |

|---|---|---|

| Estradiol, pg/ml | 36 | FP: 21.00–251.00, OP: 38–649.00, LP: <21–312 |

| Progesterone, pg/ml | 0.33 | FP: 0–1.30; OP: 1.49–5.87; LP:1.20–15.90 |

| 17-Hydroxyprogesterone, pg/ml | 574 | FP: <1000, LP: <2850, Postmenopausal<510 |

| Total testosterone, ng/dl | 207.96 | 10.83–56.94 |

| Free testosterone, pg/ml | 7.41 | Female: 7–31 |

| Dihydrotestosterone, pg/ml | 478.95 | Female: 14–15.6, male: 18–579 |

| SHBG, nmol/L | 137.63 | 26.1–100 |

| FSH, IU/L | 6.18 | FP: 3.03–8.08, OP: 2.55–16.69, LP: 1.38–5.47 |

| LH, pg/ml | 8.47 | FP: 1.80–11.78, OP: 7.59–89.08, LP: 5.18–26.53 |

| ACTH, ng/ml | 15.4 | 0–46.0 |

| Growth hormone, ng/ml | 1.21 | 0.06–5.00 |

| TSH, μIU/mL | 4.275 | 0.350–4.940 |

| fT3, pmol/L | 2.99 | 2.43–6.01 |

| Prolactin, ng/ml | 42.76 | 5.18–26.53 |

| Aldosterone, ng/dl | 23 | 3.0–23.6 |

| IGF-1, ng/ml | 100 | ’55.00–483.00 |

| PTH, pmol/L | 3.01 | 1.10–7.30 |

| 24-h urinary copper excretion, μg/24h | 1378.5 | 15–30 |

| Serum copper | 7.2 | 11.0–24.0 |

| Ceruloplasmin | 6.37 | 21–52 |

| AMH, ng/ml | >25 | Female (21–30 years old) 2.06–6.98 |

| Cortisol, μg/dl | 20 | 5.00–25.00 |

SHBG, sex hormone binding globulin; FSH, follicle stimulating hormone; LH, luteinizing hormone; ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone; fT3, free triiodothyronine; IGF-1, hepatic insulin-like growth factor-1; PTH, parathyroid hormone; AMH, anti-Müllerian hormone; FP, follicular phase; OP, ovulation period; LP, luteal phase.

The patient was diagnosed with Wilson's disease and hyperandrogenism after clinical and genetic tests. She underwent copper-chelating therapy with penicillamine and Vitamin B6 for a year, and endocrine treatment with spironolactone and ethinylestradiol/cyproterone acetate for 1 month, which was halted due to hyperkalemia and severe nausea. After 3 months, routine indicators returned to normal and testosterone levels were markedly reduced, and prolactin was restored to normal, as shown in Table S2. After one year, she reported a regular menstrual cycle. Indicators related to copper metabolism are shown in Table S2, which indicates that urinary copper levels have returned to the normal range. She was responding well to treatment, and the penicillamine dosage was tapered to 0.25mg three times a day.

Three high-frequency pathogenic mutations p.Arg778Leu, p.Pro992Leu, and p.Thr935Met are common in Wilson's disease in China, accounting for 50–60% of all pathogenic mutations.2 Two of these mutations were found in this patient. Hemolytic anemia affects approximately 5–6% of patients with Wilson's disease, resulting from excess copper ions reacting with membrane lipids and disrupting the erythrocyte membrane.1 The changes in the patient's sex hormone levels, we hypothesized that the abnormal estrogen androgen levels in this patient were due to impaired aromatase expression because of excessive copper deposition in the ovaries, which in turn affected the conversion of androgens to estrogens. Dysfunction of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis may also explain the elevated prolactin levels.

Sporadic cases of endocrine disorders have been reported in patients with Wilson's disease.3 Cases related to gonadal function are rare, mainly reporting amenorrhea, infertility, and impotence. FSH, LH, estradiol, and androgens were decreased in most cases, and androgens are elevated in rare cases.4 We also found that in addition to menstrual disorders, hyperandrogenemia, and mild elevation of prolactin, the anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) level was more than 3–5 times higher than normal, and the clinical manifestations were very consistent with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).5 Although we suspected that this patient had a combination of POCS, ancillary tests were not sufficient to confirm this diagnosis, and we could not exclude that the patient was in the early stages of PCOS. Therefore, whether abnormal copper metabolism due to mutations in the ATP7B gene is one of the etiologic factors of POCS deserves deeper consideration. In addition, her hormone levels tended to return to normal after copper chelation therapy, which supports our speculation to some extent. Of course, continued follow-up and in-depth mechanistic studies are needed to confirm our speculation.

This case report suggests that we should be aware of hereditary disorders such as WD when dealing with hemolytic anemia with a negative Coombs’ test, especially in young patients. It also deepens our understanding of endocrine disorders associated with WD and may indicate a potential association between abnormal copper metabolism in WD and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

Patient's consentThe patient provided written consent for the case report to be published.

Ethics approval statementThe study was in compliance of the declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the ethical committee of Tianjin Medical University General Hospital (Ethical no. IRB2025-YX-153-01). This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

FundingTianjin Key Medical Discipline (Specialty) Construction project (grant no. TJYXZDXK028A). Tianjin Medical and Healthcare Association (grant no. tjsyljkxh002).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data availability statementAll relevant data are included within the paper.