With the worldwide spread of mobile phones, physicians receive numerous images for clinical diagnosis of visible lesions in patients. The diagnosis through the image used for centuries has regained interest and the medical images painted on artworks allow us to see what alterations people suffered from in the past.

The Prado Museum in Madrid, Spain, holds artworks dating from the 12th century to the early 20th century with a collection of over 16,000 artistic works. It has the largest collection of paintings from the European masters of the XVI, XVII, XVIII and XIX centuries. During the Renaissance and Baroque eras, the human figure was represented in detail and realism, demonstrating the artist's in-depth knowledge of anatomy.1 Pictorical realism reflects that artist drew what they observed, and therefore depicted realistically medical conditions that the model might have had. Humanities research consists of establishing relationships between the exhibited works, dates, writings, etc., so that we reviewed medical references to detect different point of view of some researchers.2

Our hypothesis was that the artworks contained in the Prado Museum collection that follow the directives of pictorial realism depicted signs of illness, malformations, medical procedures, or tools. Our aim was to detect as many as possible the signs of disease in the published artworks of the Prado Museum.

Materials and methodsIn a first stage, the works published in the (www.museodelprado.es) webpage are reviewed by two independent observers (Juan-José Grau and Inés Bartolomé) looking for signs related to medicine. We only reviewed those that we consider the most relevant: paintings and lithography works, containing human figure sufficiently large and detailed enough to detect alterations of medical interest. We exclude those works that might lead to overdiagnosis and speculation or that they can be the result of the artist's imagination (like stigmata) or to dramatize the main content of the work (for example: the wound in the thorax caused by a spear in the descent of the cross of Jesus Christ).

In a second stage, the two independent observers met to compare and discuss the evidence found and agree on a final selection, as to minimize the potential biases of individual criteria.

We divided these images into 8 sections of medical specialties such as dermatology, surgery or medical procedures, drugs and tools, traumatology/rheumatology, endocrinology, breast disorders, ophthalmology, neurology, and maxillofacial or Ear, Nose, Throat (ENT) diseases.

We search for “Prado Museum” in medical online platforms and search engines such as PubMed and Web of Science until Dec. 31, 2021, to find published medical articles that include any of the works in the Prado Museum to compare and expand our findings.3 We also review, compare, and discuss several published books on the topic of medicine in art.

In the third stage, we put together a series of images for each specialty showing the paintings we had selected and sent them to a medical specialist of each field from University of Barcelona/Hospital Clínic Barcelona. They made suggestions or pointed out relevant details and either confirmed or rejected our initial diagnosis. Our list of selected works was corrected according to their advice.

The results were analyzed using descriptive statistics and measuring global prevalence rates.

ResultsWe revised a total of 16,568 works that the museum holds and grants the access. From all of them, we selected 5490 pictorial works to be studied including 1708 works that the museum currently exhibits that were revised “in situ”. We detected 121 paintings (see Annex), and a total of 145 images corresponding to signs of disease. This means a 2.2% of selected paintings in the Prado Museum show clinical signs of disease or images related to the medical field. We divided these images into 8 sections of medical specialties (Table 1).

Art Works and Medical Images according to the different sections.

| SECTION/SPECIALTY | Work number | /Medical Images number | % |

| n=121 | /n=145 | ||

| DERMATOLOGY | 38 Trichoepithelioma 1 | Epithelioma 2 | 31% |

| Aracnodactily 1 | Rhinophyma 4 | ||

| Seborreic Keratosis 5 | Hypothyroidism 1 | ||

| Nevi 4 | Rosacea 4 | ||

| Scleroderma 1 | Lipoma 3 | ||

| Lentigo 4 | Tinea capitis 4 | ||

| Acinic Keratosis 2 | Plague Sequel 1 | ||

| Basal Cell Carcinoma 2 | Varicose | ||

| Ulcer/depigmentation 2 | |||

| Leprosy 1 | Hirsutism 2 | ||

| Melanosis 1 | Alopecia 1 | ||

| Distrophy 2 | *Eye Enucleation 1; | ||

| Crutches 1;Patch 1 | |||

| MEDICAL PROCEFURES | 25 Healing Oil 1 | Dental Extraction 3 | 21% |

| Crutches/stretcher 4 | Pactch 3 | ||

| Trepanation 2 | Medical Visit 1 | ||

| Smoking 3 | Enema 1 | ||

| Pharmacopeia 1 | Vaccination 2 | ||

| Surgery (other) 2 | Autopsy 1 | ||

| Bandage 1 | Corpses 1 | ||

| TRAUMATOLOGY/ | 13 Skeleton Disorders 6 | Nerve Palsy 1 | 11% |

| REUMATOLOGY | Surgery 2 | Luxation 1 | |

| Preater Hand 2 | Tophus 1 | ||

| Arteritis 1 | |||

| ENDOCRINOLOGY | 12 Goiter 5 | Dwarfism 2; Cretinism 2 | 10% |

| Obesity 3 | *Lipothymia 1; Erisipela 1; | ||

| Nerve Palsy 1 | |||

| BREAST DISORDERS | 11 Senescence 1 | Mastectomy 6 | 9% |

| Fibrosis 2 | Breast Cancer 1 | ||

| Polymastia 1 | Skeleton Disorders 1 | ||

| *Artritis 1 | |||

| OPHTALMOLOGY | 10 Trachoma 2 | Strabismus 1 | 8% |

| Caustication 1 | Phytisis Bulbi 1 | ||

| Blindness 3 | Atrophy 2, Glasses 1, | ||

| *Dwarfism 1 | |||

| NEUROLOGY | 7 Ulnar Nerve Palsy 2 | Obstetric Palsy 1 | 6% |

| Median Nerve Palsy 4 | *Dwarfism 1 | ||

| MAXILLOFACIAL/ENT | 5 Adenophaties 1 | Facial/Frontal Alteration 1 | 4% |

| Parotid Disorder 2 | *Glasses 1, Aracnodactily 1 |

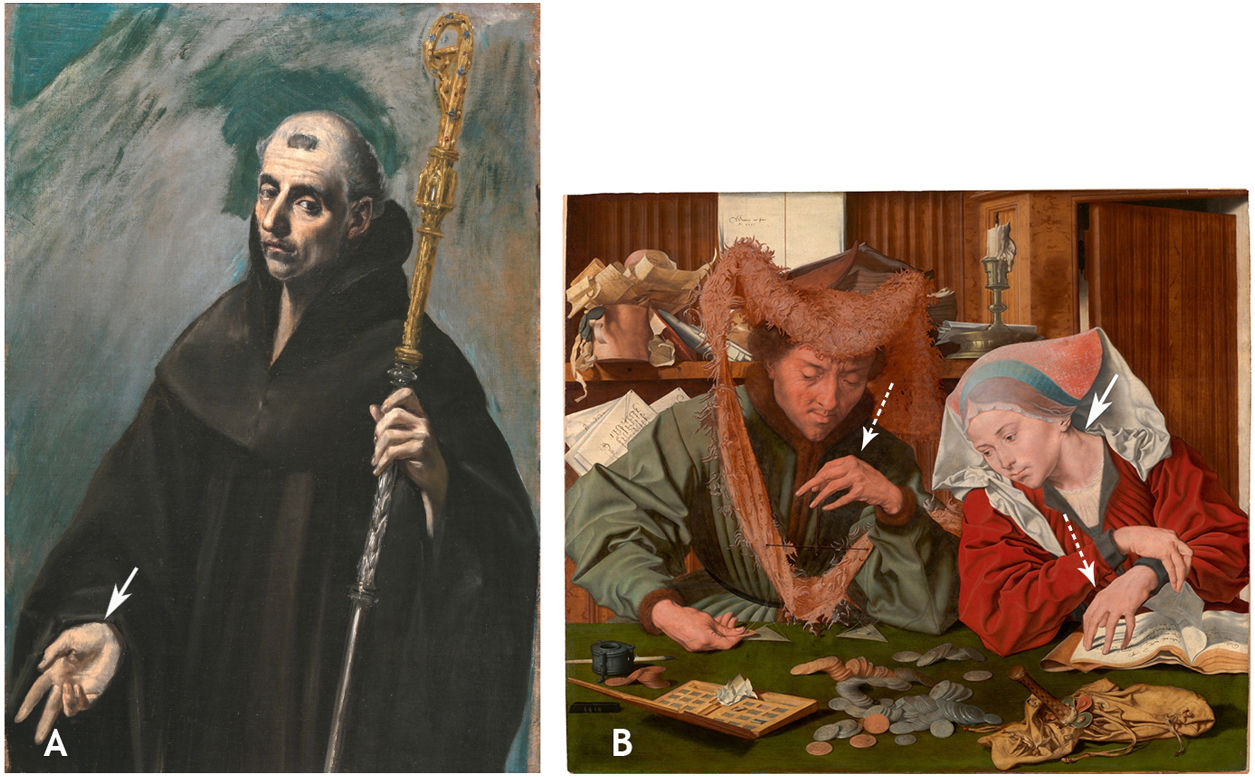

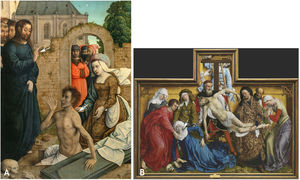

The 121 paintings with medical images, include 38 works in the dermatology section (31%) (Fig. 1A); 25 works in the medical procedures, tools and drugs section (21%) (Fig. 1B); 13 works in traumatology/rheumatology (11%) (Fig. 2A); 12 works in endocrinology (10%) (Fig. 2B); 11 works in breast disorders (9%) (Fig. 3A); 10 works in ophthalmology (8%) (Fig. 3B); 7 works in neurology (6%) (Fig. 4A); and 5 works classified as maxillofacial or ear, nose and throat (ENT) (4%) (Fig. 4B).

(A) “SaintHieronymus”. Marinus Van Reymerswaele, XVI century Aracnodactyly (arrow) and Seborrheic Keratosis (arrow). (B) “María Luisa de Parma, queen ofSpain”. Francisco de Goya, Replica. The velvet patch on her temple (arrow) probably was dabbed with morphine to alleviate migraines; a forerunner of the fentanyl patches we use today.

(A) “The raising ofLazarus”. Juan de Flandes, 1514–1519. Lazarus is portrayed with a dislocated left shoulder that could be a result of a seizure (arrow). There is also an example of a Hand of Benediction (Christ), related to a nerve palsy or Dupytren's disease (dotted arrow). (B) “The Descen from theCross”. Rogier van der Weyden, 1443. In the figure with the blue dress a diffuse goiter can be seen (arrow). She also is the representation of an emotional syncope.

(A) “Saint Agatha”. Veronese, 1590–93. A sharp cut of mastectomy can be observed (arrow) with therapeutic intention because of the help of an Archangel. On the left is a bottle with healing oil (dotted arrow). (B) “Tobias Healing hisFather”. Bernardo Strozzi, 1640–44. Alcali caustication in both eyes (arrows).

In 14 paintings we found two different images of disease and 5 other paintings we found 3 images of disease (Fig. 1A).

Of these 145 images, the highest global prevalence rates include: 14 depictions of surgical procedures (9%) (including 6 images of mastectomy), 12 examples of dwarfism (8%), 11 nerve palsies (8%), 7 keratosis (5%), and 9 examples of blindness (6%).

Of the total of 121 artworks with medical signs, in 51 (42%) comments of disease have been previously published, meaning the remaining 70 (58%) have been detected or proposed for the first time by us in this work.

DiscussionTo the best of our knowledge this is the first systematic study that reviewed the pictorial artworks found in the Prado Museum looking for sings of disease or medical alterations taking advantage of the facilities and quality of the images offered by museum website. Obviously, the diagnoses are only speculative since the final diagnosis would require a laboratory study or a pathological study.

The most obvious conditions to be detected through observation were dermatological diseases because the skin is exposed. The portraits allow us to clearly differentiate several skin lesions like lentigines, seborrheic keratosis, actinic keratosis, nevus and even possible melanoma as in “IsabellaFarnesse” by Meléndez, and basal cell carcinomas in “Saint James the elderapostle” by El Greco.1

Lentigines, like the ones found in “SaintLuke” by Wolfordt, “The apostle SaintPeter” (anonymous) or “OldSpinning” by Murillo are defined as small, flat and pigmented spots on the skin, with clearly defined edges that are surrounded by healthy skin.4,5

In “Portrait of an OldMan” by Joos van Cleve shows a man with a significantly enlarged nose, bulbous and misshapen. These traits, along with subtle malar telangiectasias suggest a rhinophyma (sebaceous tissue hypertrophy which causes outgrowth) probably related to alcoholism, although we cannot discard other causes such as rosacea.6 An example of alcohol-induced rosacea can be seen in “The Feast of Bacchus”, by Velázquez.7

In “Boys pickingfruit” by Goya, a “Boy climbs atree” and “Shakes the branches so his friends can pick up thefruits”, the boy on all four has a patch of alopecia. In “Boys climbing atree” also by Goya, three kids help each other to collect berries. The bare-footed boy on all four has a universal alopecia with a scarring area.8 In “Thewedding” by Goya, right next to the one-eyed man of the sardonic smile, stands a boy, facing backwards with a striking lesion on his scalp; of irregular edges and scarring characteristics, which is a favus too, tinea capitis, also known as “ringworm of the scalp” or “tinea tonsurans”, a dermatophytosis caused by Tricophyton that invades the hair shaft.

In “SaintRoch” by José de Ribera, we can see the patron of epidemics that worked all his life helping those affected by the bubonic plague. Not surprisingly, he himself suffered it as is suggested by a bubo, which is easily identified on his leg.9

There are several examples of surgical procedures, like “The extraction of the Stone ofMadness” by Hieronymus Bosch that shows the removal of a “madness stone” by a trepanation-like surgery. Popular tradition associated madness with a stone lodged in the brain, and therefore some people sought to remove it. The charlatan or surgeon performing the operation wears an upside-down funnel, which “symbolizes deception and reveals that he is not a learned man but a fraudster”.10–12 Other striking details we included in the tools section are patches. Queen Mary Louise of Parma appears in two portraits by Goya. First in María “Luisa de Parma, Qeen of Spain” (Fig. 1B) second in “Qeen Maria Louise with Toil”. Also, King's sister Maria Jose in other portrait (“The Family of CarlosIV”) all the three are wearing what seems to be a velvet patch on her temple. The fashion for wearing patches, which were smeared with ointment to attach them to the skin is thought to have begun in France and then spread across Europe to enhance the whiteness of the wearer's flesh. However, it appears that patches might also be thought to alleviate certain ailments, particularly toothaches, headaches, and migraines, as would be the case here, given the location.3,13,14

In the section rheumatology/traumatology, we want to highlight a gouty tophus in the right hand in “Aesop” by Velazquez as a consequence of gouty arthritis frequent in the sixteenth century.12 Also, arteritis of the temporal artery (Horton's arteritis) in “Christ embracing saintBernard” by Francisco Ribalta. Temporal arteritis is an inflammatory giant cell vasculitis that tends to affect elderly patients and is characterized by a temporal headache and a fever with enlargement of temporal artery possibly due to the involvement of branches of the external carotid artery.15 It is usually treated by internits or rheumatologists. Hypermobility syndrome and Trendelenbung sign can also be seen in “The ThreeGraces” by Rubens as a hereditary rheumatologic signs.16

We can also see an amputation of a leg with gangrene and infection that has been transplanted to another person, representing the myth of “The miracle of Saint Cosmas and SaintDamian” published by other authors.9,12 Acquired or genetic orthopedic alterations such a short stature are also depictec. The most common and recognizable form of dwarfism is achondroplasia, which accounts for 70% of cases, due to a mutation in the fibroblast growth factor 3 gene. This form of dwarfism is characterized by an average-sized trunk with short limbs and a larger forehead.17

In “The Resurrección ofLazarus” (Fig. 2A), by Juan de Flandes is a very interesting example of how medicine can complement the study of art and its histories. According to the Bible, Lazarus had been dead for 4 days before he was resurrected by Jesus. This is the precise moment that Juan de Flandes paints. In this painting, Lazarus has a dislocated left shoulder. Knowing that epileptic seizures can cause joint dislocations, could Lazarus (the model in this paint) have been mistakenly considered dead, when perhaps, he had in fact suffered a seizure.12

Feature related to endocrinology was thyroid swelling, which is present in many paintings and sculptures of the Renaissance and Baroque eras, such as “The descens from theCross” by Weyden (Fig. 2B), or “The Holy Family with the infant Saint John theBaptist” by Raffael, or “The Virgin and Child, known as the DuranVirgin” by Weyden. It is a debated subject, as it is not always clear whether it is a realistic representation, or a detail added by the painter. It is commonly thought that some artists considered an enlarged female neck as a sign of prosperity, and therefore added this feature to normal subjects; this has been called “pseudogoiter”.18

Velázquez, as many of his contemporaries, was also interested in court jesters. But in “Maids ofHonor” (Las Meninas) by Velazquez we can see at least two short stature models whose appearance is characteristic of hypothyroidism also called cretinism. Individuals with defects in thyroid hormone synthesis will often have a goiter while those attributed to the transplacental passage of blocking antibodies from the mother or to thyroid dysgenesis will not.9 Severe developmental and physical delays occur by six months of age, and while treatment in infancy can reverse the physical changes, it cannot reverse the neurological damage. The discovery of iodine and its importance in thyroid gland development toward the end of the 19th century led to public health measures, and cretinism has now been largely eliminated in the developed world20 A current problem for endocrinologists is childhood obesity, which is represented in “Eugenia MartinezVallejo” by Juan Carreño de Miranda. Some authors point out that he could suffer from Cushing's syndrome, but the distribution of body fat and the absence of skin striations would go against said syndrome.13,19,20

In “The threeGraces”, by Rubens, we can see that the model on the right has an open ulcer with reddening of the skin, nipple retraction, reduction of breast volume as well as axillar lymph nodes. We do not have the pathology study of these diseases, but from a clinical point of view, the lumps in her breast make cancer the most likely diagnosis. This is perfectly compatible with the typical appearance of a locally advanced breast cancer.21

This Rubens’ work was probably influenced by other painting from Titian that, perhaps, could be seen during his visits to Spain.22

During that time excision was used for small breast tumors. Sometimes total mastectomy was performed (Fig. 3A). Hemostasis was achieved by compression, cautery, or suture ligatures. On the other hand, locally advanced non operable breast cancer was treated with diet, phlebotomies, or topical caustics.23 There is another possible breast cancer in early stage depicted in “Diana and her nymphs surprised bysatyrs”.24

Also, we found several paintings of “SaintAgatha” (by Giordano Luca, Veronese, Vaccaro or Giovanni Martinelli) with one common characteristic: she is mastectomized. Saint Agatha is a Christian saint born in Sicily in the 3rd century AD. According to written tradition, Agatha made a vow of virginity and rejected the Roman prefect Quintianus. Knowing she was a christian, he had her arrested, imprisoned in a brothel, put in jail, and tortured. Amongst the tortures she underwent, was the cutting off her breasts. That night she received the visit of Saint Peter and an angel, and her breasts grew back. She is the patron of rape victims and breast cancer (among others).25

In the field of ophthalmology, “Tobias healing hisFather” by Strozzi (Fig. 3B), is the most remarkable example. Tobias's father was blinded when bird droppings fell directly into his eyes. This probably caused a chemical burn because bird droppings have high concentrations of ammonium and nitrates. In “Tobias healing hisFather”, Tobias, following the Archangel Rafael's directions, applies the fish's gall to his father's eyes, curing his blindness. The ‘white film’ that according to the Bible ‘scaled off from the corners of his eyes’ corresponds to the exudate of a purulent conjunctivitis, probably result of a bacterial infection.13,26 “Adoration of the Tomb of Saint PeterMartyr” by Berruguete, “A blind Hurdy-Gurdyplayer” by La Tour or “The blindguitarist” by Goya are only a few examples of representations of blindness in art. Although there are several causes for blindness some of these examples might correspond to trachoma, very prevalent in 1778 when the work was done. The initial infection by Chlamydia trachomatis causes a purulent conjunctivitis (which can lead to blindness due to pannus formation). The scratching of the cornea by the lashes eventually leads to corneal ulceration, scarring, opacity, and permanent blindness. Although it is impossible to ascertain the cause of blindness in most of the portraits, it is sensible to presume some of then could have been caused by trachoma.13

In neurology section there are several representations of the Hand of Benediction in art (Fig. 2A). The origin of this gesture has been widely discussed, but a consensus has never been reached. If we consider this hand posture as pathological in its origin (before being adopted as symbolical) there are various possibilities, the most accepted being the median nerve palsy. If someone with a median nerve injury tried to make a fist, the 2nd and 3rd fingers would remain in extension, thus making a benediction sign. On the contrary, if an ulnar nerve injury was present, a person trying to open their hand would be left with their fourth and fifth fingers flexed, resulting in the same final hand position (Fig. 4A). An open hand has always been the standard position of greetings, so the ulnar nerve etiology is the more plausible option.27 It also has been proposed that the Hand of Benediction derives from the Hand of Sabazios, a sculpture of the hand of the Thracian and Phrygian god Sabazios, adopted by the Romans and later by the early Christians, who “took over” the language of the pagan motifs.28 Alcohol consumption has been linked to Dupuytren disease, whether this indicates an understanding of the relationship at the time is hard to say.

In ENT, in “The Moneychanger and hisWife”, by Marinus van Reymerwaele (Fig. 4B), the woman clearly has a swollen neck, presumably because of cervical lymphadenopathies. Based on the location of these lymph nodes, we classify them in areas II or III: upper jugular nodes or middle jugular nodes. Based on the drainage of these areas, whose primary lesion would come from the left tonsil or oropharynx, differential diagnoses include infections, such as mononucleosis, tuberculosis, toxoplasma, cytomegalovirus, or tumors such as lymphomas or head and neck squamous cell carcinomas.29 In this work can also be seen alterations in the hands of the models suggesting aracnodactilia possibly because of a hereditary Marfan syndrome or other rheumatologic conditions.30

The main weaknesses of this article is that we do not have a biopsy or confirmatory analysis of a disease and because of an excessive length of the subject, we have omitted many comments on various works of art or on a specific work of art that many of the readers could offer, but we have made a review of those that we have considered more interesting under our point of view. The strength of this study has been that it has attempted to follow an objective scientific method for better interpretation of clinical signs and medical images.

We can conclude that a considerable number of medical conditions can be seen in many of the paintings in the Prado Museum that follow the style of pictorial realism. The confrontation of what has already been published in the fields of medicine and history of art, and the information obtained by us, offers a great insight into the history of medicine, to understand both the diseases and the treatments that were available. The museum's webpage offers resources that are extremely valuable and a great opportunity to see clinical signs of many diseases allowing further research.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

We would like to acknowledge with much appreciation the role of everyone who contributed with their expertise in comments and suggestions. In special to: Antonio Vilalta MD, Dermatologist, Ex-staff member of Dermatology department of Hospital Clinic of Barcelona (HCB); Carles Conill MD, PhD, Radiotherapy Oncologist, HCB and Associate Professor of the UB; Isabel Vilaseca MD, PhD, head of the ENT unit at HCB and Full Professor of University of Barcelona (UB); Irene Halperin MD, PhD, endocrinologist in HCB and Associate Professor of the UB; Ricardo Casaroli, ophthalmologist in HCB and UB professor; José María Arandes MD, PhD, traumatologist in HCB; Maria Cinta Cid MD, PhD, Autoimmune diseases unit HCB and Professor of the UB; Laura Oleaga MD, PhD, radiologist in HCB and Professor of the UB; Prof Dr. Albert Biete MD, PhD, Radiotherapic Oncologist at HCB and Full Professor of the UB and Francisco Avia, Clinical Photographer at HCB.

Complete list of selected works, divided by medical specialty and visual reference (Work title, Author; MEDICAL SIGNS)

- 1.

DERMATOLOGY (38 works)

- •

Saint Hieronymus. Marinus Van Reymerswaele, XVI century ARACNODACTYLY AND NEVUS

- •

Baccus acomppained by nymphs and satyrs. Anonymous (Copy of Vos, Cornelis de), XVII century SEBORRHEIC KERATOSIS, MULTIPLE NEVI, SCLERODERMA (6)

- •

Saint Luke. Artus Wolfordt, XVI century LENTIGO ON RIGHT CHEEK

- •

An Evangelist. Guido Reni, XVII century. ACTINIC KERATOSIS

- •

Saint Hieronymus. Guido Reni, XVII century. KERATOSIS AND POSSIBLE BASAL CELL CARCINOMA RIGHT EYE

- •

Saint Francis embracing a leper. Zacarias González Velázquez, 1787 LEPROSY

- •

The apostle Saint Peter. Anonymous, XVII century. LENTIGO ON RIGHT CHEEK AND SUBUNGUAL MELANOSIS

- •

Saint James the elder. El Greco, 1608–1614. BASAL CELL CARCINOMA ON THE NOSE

- •

Saint Monica. Luis Tristán, 1616. LACK OF BICHAT BAGS (FACIAL DISTROPHY)

- •

The agony in the garden. Juan de Flandes, 1514–1519. EPITHELIOMA ON FACE AND EAR

- •

Christ before Pilate. Francisco de Osona, 1500. RHINOPHYMA AND HYPOTHYROIDISM

- •

The crowning with Thorns, 1590–1598. Leandro Bassano. RIGHT CHEEK TUMOR AND RINOPHYMA

- •

Old spinning. Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, XVII Century. LEFT SUPRACILIAR LENTIGO

- •

Water room in Madrid. Galician water carriers. Rodríguez de Guzmán, 1859. ROSACEA (right figure)

- •

The Poet Manuel José Quintana. José Ribelles y Helip, 1806. NEVUS ON THE FACE (4 p. 205)

- •

Francisco Pacheco. Velázquez, 1620. KERATOSIS RIGHT EYELID

- •

El pintor Francesco Albani 1635. Andrea Sacchi.NEVUS ON THE FACE

- •

Self-portrait. Bonnat, Joseph León, 1918. SEBORRHEIC KERATOSIS

- •

The actor José Riquelme In ‘The famousColirón’. Viniegra y Lasso de la Vega, Salvador, 1904. LIPOMA OR CYST

- •

Portrait of an Old Man. Joost van Cleeve, 1525–1527. ACNE ROSACEA AND RHINOPHYMA (4 p. 121–6,12p. 88)

- •

Menippus. Velazquez 1639–1642). RHINOPHYMA (4p:120)

- •

José Collado y Mata. Palmaroli y González, Vicente, 1868. LENTIGO, LIPODISTROPHY

- •

The Painter Francisco de Goya. Vicente Lopez Quintana 1828. SEBORRHEIC KERATOSIS (4 p. 191)

- •

Nicolas Omazur. Murillo 1672. FRONTAL LIPOMA (4 p.195)

- •

Félix Máximo López, First Organist of the Royal Chapel 1820. López Portaña, Vicente. SEBORHEIC KERATOSIS

- •

Boy climbs a tree. Goya, 1791–1792. TINEA CAPITIS (4 p. 179, 8, 9 p.103)

- •

The wedding. Goya y Lucientes, 1791–1792. TINEA CAPITIS. ENUCLEATION OF AN EYE.(4 p. 180)

- •

Boys picking fruit. Goya, 1791–172. TINEA CAPITIS (4 p.178)

- •

Saint Roch. José de Ribera, 1631. PLAGUE SEQUEL, RIGHT LEG TUMORATION

- •

Saint Elisabeth of Hungary. Lythography by Murillo, 1868. VARICOSE ULCER, TINEA CAPITIS, CRUTCHES (8)

- •

The feast of Bacchus. Velázquez, 1628–1629. ROSACEA BY ALCOHOLISM (4p:109,8)

- •

Brígida de Rio. The Bearded Lady. Sánchez Cotán, 1590. HIRSUTISM (4 p. 168,12 p. 117, 13 p. 51)

- •

The Bearded Lady. José de Ribera. HIRSUTISM (4 p.169)

- •

Mrs. Delicado de Imaz. Vicente López Portaña, 1836. HIRSUTISM (4 p.172-3)

- •

Mary, lady Van Dyck. Anton Van Dyck, 1640. ANDROGENIC/FIBROSING ALOPECIA (4 p.184)

- •

Isabella Farnese. Miguel Jacinto Meléndez, 1718–1722. NEVUS/MELANOMA OR VELVET PATCH (4 p.218)

- •

The King drinks. Teniers the younger, 1650–1660. ALCOHOLISM ROSACEA

- •

Christ presents the Redeemed from Limbo to the Virgin 1510–1518. Fernando Yáñez de la Almedina. VARICOSE VEINS IN THE LEGS WITH DEPIGMENTATION

- 2.

MEDICAL PROCEDURES DRUGS AND TOOLS (25 works)

- •

Venus healing Aeneas. Blondel, MerryJoseph, 1805–1810. WOUND-HEALING OIL

- •

Saint Sebastian speaking to Marcus and Marcellian and Saint Sebastian and Saint Polycarp destroying Idols. Pedro García de Benabarre, 1470. CRUTCHES

- •

The miraculous spring at the Saint Bruno's Thomb. Vicente Carducho, 1626–1632. CRUTCHES

- •

The Extraction of the Stone of Madness. El Bosco, 1501–1505. TREPANATION (11 p. 142–3,12 p. 66)

- •

The Surgeon or The Extraction of the Stone of Madness. Jan Sanders Van Hemessen, 1550–1555. TREPANATION (13 p.196, 19 p.120–1)

- •

Smokers and Drinkers. David Teniers, 1652. SMOKERS

- •

Smokers in a Tavern. David Teniers, 1635. SMOKERS

- •

The Merry Soldier. David Teniers, 1631. SMOKERS

- •

The Alchemist. David Teniers, 1631–1640. PHARMACOPEA (8)

- •

The Surgical Operation. David Teniers, 16311640. SURGERY (8,9 p.108,13 p.37)

- •

The First Shot. Enrique Esteban y Vicente, 1892. SURGICAL BANDAGE

- •

The Tooth Puller. Leonardo Alenza y Nieto, 1844. DENTAL EXTRACTION

- •

The Tooth Extractor. Theodoor Rombouts, 1620–25. DENTAL EXTRACTION (8,12 p. 110,13 p. 200)

- •

Father Bernard Praying in the Portes Charterhouse. Vicente Carducho, 1632. CRUTCHES AND STRETCHER

- •

The Haywain Triptych. El Bosco, 1516. DENTAL EXTRACTION

- •

María Luisa de Parma, Qeen of Spain. Francisco de Goya, reply. VELVET PATCH (4pp:193)

- •

Qeen Maria Louise with Toil. Francisco de Goya, 1746. VELVET PATCH

- •

The Family of Carlos IV; Goya 1800; VELVET PATCH (4 p.192)

- •

Saint Luck. Juan de Sevilla, 1401–1435. SURGERY (8)

- •

The Triumph of Death. Pieter Bruegel The Elder. MANAGEMENT OF CORPSES

- •

A Hospital Ward During the Visit of the Chief Physician. Luis Jiménez, 1 889. MEDICAL VISIT(12 p.190, 19 p.51–2)

- •

The enema. Eugenio Lucas Velazquez. 1855. ENEMA (12 p.180)

- •

Vaccination for Children. Vicente Borrás, VACCINATION (13 p.148–51)

- •

Vaccination Center. Manuel Gonzalez Santos. 1900. VACCINATION

- •

and he was Right. Enrique Simonet1890. AUTOPSY. (13 p.140–1)

- 3.

TRAUMATOLOGY/RHEUMATHOLOGY (13)

- •

Eve. Albrecht Dürer. 1507. KYPHOSCOLIOSIS

- •

Miracles of the Doctors Saints Cosmas and Damian. ORTHOPEDIC SURGERY; PREATER HAND

- •

Christ embracing Saint Bernard. Ribalta, Francisco, 1625–1627. GIANT CELL ARTERITIS (HORTON'S DISEASE)

- •

The Ressurrection of Lazarus, 1514–1519. Juan de Flandes. EPILEPTIC SHOULDER; MEDIAN NERVE PALSY (monk). (12 p.78)

- •

Dwarf with a Dog. Velázquez, 1645. ACHONDROPLASIA (8)

- •

The buffoon El Primo. Velázquez, 1644. ACHONDROPLASIA (8,12 p.127)

- •

Portrait of a Darf. Hamen y León, Juan van der, 1626. ACHONDROPLASIA

- •

The Strolling Players. Goya, 1793. ACHONDROPLASIA

- •

The Jester Sabastian de Moura. Velazquez.1645. ACHONDROPLASIA (8,13 p.201)

- •

Infanta Isabel Claraeugenia and Magdalena Ruiz. Sanchez Coello 1587. ACHONDROPLASIA. (12 p. 105)

- •

Aesop (copy); Velazquez. GOUTY TOPHUS IN RIGHT HAND (12 p.130)

- •

Miracles of the Doctors Saints Cosmas and Damian. Fernando Rincón. ORTHOPEDIC SURGERY, PREATER HAND (9 p.98,12 p.61,13 p.193)

- •

Saint Hippolyte curing the leg of Oxherd Peter. Lluis Borrasà.1490. ORTHOPEDIC SURGERY

- 4.

ENDOCRINOLOGY (12 works)

- •

The Holy Family with the Infant Saint John the Baptist. Andrea del Sarto, copia XVI. GOITER

- •

Cupids making a Bow: Winter. Siglo XVII. Anonymous. CHILDHOOD OBESITY–PSEUDOGYNECOMASTIA

- •

Saint Barbara; Campin, Robert 1538; GOITER

- •

The Virgin and Child, known as the Duran Virgin. van der Weyden R.1435. GOITER (17)

- •

The Descent from the Cross. Rogier van der Weyden, 1443. GOITER, LIPOTHYMIA (19 p.206–7)

- •

Eugenia Martínez Vallejo, Naked. Carreño de Miranda, Juan, 1680. OBESITY (4 p.160–1, 6, 12 p.144,13 p.74–8, 19 p.138–9)

- •

Eugenia Martínez Vallejo, Clothed. Carreño de Miranda, Juan, 1680. OBESITY(4 p.160–1,12 p.144,13 p.204,8)

- •

Portrait of Dwarf. John Closterman. XVII. GROWTH HORMONE DEFICIENCY (PROPORTIONATE DWARFISM) (8)

- •

Prince Philip and the Dwarf Miguel Soplillo. Rodrigo Villadrando.1620. GROWTH HORMONE DEFICIENCY (PROPORTIONATE DWARFISM) (4 p.158, 8 p.112)

- •

The Boy from Vallecas (Francisco Lezcano) Velazquez. 1635–1645. CRETINISM (4 p.162–3,8, 12 p.125)

- •

Maids of Honor (Las Meninas) 1656; Velazquez, Diego; CRETINISM (2, 8,12 p:135)

- •

Christ Pantocrator surraunded by the Tetramorph, altar frontal, Salanllong (Ripoll). Master of Llluçà. 1200; GOITER; ERISIPELA; MEDIAN NERVE PALSY

- 5.

BREAST DISORDERS (11 works)

- •

The Ages of Women and Death. Hans Baldung Grien, 1541–1544. MAMMARY SENESCENCE (4 p.27,13 p.167)

- •

Nymphs and Satyrs. 1615. Rubens. RETRACTILE CUTANEOUS FIBROSIS UNDER RIGHT BREAST. LIPODYSTROPHY

- •

Abundance.1625. Jan Brueghel the younger. POLYMASTIA

- •

Diana and her Nymphs Surprised by Satyrs. Rubens, 1639–1640. LEFT MAMMARY GLAND UMBILICATION

- •

Saint Agatha. Veronese, Carletto, 1590–93. MASTECTOMY; CURATIVE OIL

- •

Saint Agatha. Andrea Vaccaro, 1635. MASTECTOMY (8)

- •

Saint Agatha in prison. Andrea Baccaro. XVII. MASTECTOMY.

- •

St Agatha Cured by St Peter in Prision. Giovanni Martinelli, XVII. MASTECTOMY

- •

Saint Agatha. Giordano, Luca. 1680–86. MASTECTOMY

- •

Saint Agatha.1798. Taille douce: etching and engraving on wove paper. VÁZQUEZ, JOSÉ-ENGRAVER-(AFTER VACCARO, ANDREA). MASTECTOMY

- •

The Three Graces. Rubens, 1630–35. BREAST CANCER; RHEUMATOID ARTRITIS AND TRENDELEMBURG SIGN (16,20,21,23)

- 6.

OPHTALMOLOGY (10 works)

- •

Adoration of the Tomb of Saint Peter Martyr. Pedro Berruguete, 1493–99. TRACHOMA

- •

Tobias Healing his Father. Bernardo Strozzi, 1640–44. ALCALI CAUSTICATION (26)

- •

A Blind Hurdy-Gurdy Player. Georges de La Tour, 1620–1630. BLINDNESS (26)

- •

A Blind Musician. Ramón Bayeu, 1786. TRACHOMA/OTHER CAUSES OF BLINDNESS/SYMBLEPHARON/ENTROPION

- •

Equestrian Portraid of the Duke of Lerma. Rubens, 1603. STRABISMUS DUE TO AMBLYOPIA

- •

Blind Guitarrist. Goya, 1778. BLINDNESS

- •

The Sense of Touch. José de Ribera, 1632. PHYTISIS BULBI (12 p.118)

- •

Pedro Benítez and his Daughter María de la Cruz. Rafael Tegeo, 1820. OCULAR TRAUMA IN CHILDHOOD, EYELID PTOSIS WITH OCULAR ATROPHY AND CORNEAL OPACIFICATION

- •

Self-portrait; Lucca, Giordano (copy); GLASSES FOR HYPERMETHROPY

- •

The Buffoon Calbacillas. Velazquez, Diego. DWARFISM. ANOPHTHALMIA, MICROPHTHALMIA

- 7.

NEUROLOGY (7 works)

- •

Saint Gregory. Juan de Nalda, 1500. ULNAR NERVE PALSY

- •

Saint Christopher/The Virgin announced (reverse). XVI Century. MEDIAN NERVE PALSY

- •

Christ between the Virgin Mary and Saint John the Baptist. Jan Gossaert, 1510–1520. MEDIAN NERVE PALSY

- •

Saint John the Evangelist with two Ladies and two Girls/Saint Hadrian. Pieter Coecke van Aelst, 1532. MEDIAN NERVE PALSY

- •

San Benito. El Greco, 1577–1579. ULNAR NERVE PALSY

- •

The Guils Frontal. XIII. MEDIAN NERVE PALSY

- •

Perejón, Buffoon of the Count of Benavente and of the Grand Duke of Alba. Antonis Mor. 1560. OBSTETRIC PARALYSIS; DWARFISM (8)

- 8.

MAXILLOFACIAL/EAR, NOSE, AND THROAT (5 works)

- •

The Moneychanger and his wife. Marinus van Reymerswaele, 1539. CERVICAL ADENOPATHIES AND ARACHNODACTYLY.

- •

The Musicean Enrique Liberti. Van Dyck, 1627–32. SUBMAXILAR AND PAROTID HYPERTROPHY (6)

- •

The Martyrdom of Saint Catherine. 1500, Gallego, Fernando (cercle). FACIAL MALFORMATIONS (MICROGNATHIA)

- •

The Death of the Virgin. Master of La Sisla. 1500. FRONTAL BONE ENLARGEMENT.GLASSES

- •

The Descent of the Cross. Pedro Machuca. 1547. CHILDHOOD PAROTIDITIS