The transition from an industrial-based society to a knowledge-based society marks one of the most profound societal transformations of the modern era. This shift is driven by scientific progress, technological advancements, and innovation, thereby shaping economies and social structures. Despite the widespread use of the term “knowledge society,” its definition remains under debate, and its measurement poses significant challenges. This paper examines various perspectives on the Knowledge Society, and proposes a definition rooted in scientific and technological progress while acknowledging the role of ICT, globalisation, and education.

A comprehensive literature review and bibliometric analysis are conducted to assess dominant themes and trends in academic discourse. Furthermore, this study evaluates existing proxy indicators and proposes a novel framework to measure the progress of economies towards a Knowledge Society. Using data from international institutions, this paper analyses the global trends over the past fifty years and assesses the extent to which a fully-fledged Knowledge Society has been realised.

However, this transition is not without challenges. The Knowledge Society relies on highly skilled labour, which raises concerns regarding job displacement due to automation and artificial intelligence. Intellectual property regulations further complicate global knowledge dissemination. Moreover, ensuring that scientific progress aligns with sustainability goals is crucial when addressing ecological concerns such as e-waste and high energy consumption.

Ultimately, the Knowledge Society represents a paradigm shift with significant economic and social implications. By addressing its limitations, societies can harness its potential to drive inclusive growth, innovation, and sustainable development.

The concept of the Knowledge Society has gained prominence in recent decades and describes a social and economic structure in which knowledge functions as the primary driver of development. Peter Drucker first introduced this term in The Age of Discontinuity (Lipkowitz, 1969), when he emphasised the central role of knowledge in wealth creation and the need for an economic theory that placed it at the core of productive activity. Since then, numerous authors have explored and expanded the concept from a wide variety of perspectives: economic, social, political, and ethical (Stehr, 1994; David & Foray, 2003; Lor & Britz, 2007; Cernat, 2011).

To further complicate matters, the term Information Society (Masuda, 1981) is sometimes used interchangeably with that of Knowledge Society, without acknowledging their distinct characteristics and implications. However, several authors have highlighted a clear distinction between the two concepts (Abramova & Popva, 2018; Kabir, 2013). Advances in information technology (IT) have brought about disruptive changes in all aspects of society, including both productive and social relationships (Castells, 1996). Information technology is also directly related to the promotion of the Knowledge Society, and an analysis of knowledge production from an information systems perspective is therefore vital (Mansell, 2012). Nevertheless, both concepts, Information Society and Knowledge Society, must be independently defined and addressed.

Beyond classical theories, recent contributions have reinterpreted the Knowledge Society through new and complementary lenses and have broadened its scope beyond strictly economic and technological paradigms. These updated perspectives emphasise a more complex and multidimensional understanding of how knowledge operates across social, cultural and institutional contexts. From this vantage point, the contemporary Knowledge Society can be examined through several interrelated dimensions that shape both its internal structure and its global influence. Information technology remains a foundational pillar, and fosters innovation and enhances competitiveness, particularly in education, where it enables highly efficient knowledge management and supports collective problem-solving (Sharma & Tarmali, 2023). Intellectual capital, understood as competencies, knowledge, networks, and innovation capabilities, has become a strategic asset in higher education, and has enhanced staff value and contributed to institutional development, innovation, and socio-economic impact (Ibarra-Cisneros et al., 2023). In the Knowledge Society, higher education fosters digital competences that help individuals transform information into knowledge and adapt to rapidly changing, digitally mediated learning environments (Zhao et al., 2021). In parallel, the Knowledge Society has increasingly been associated with values such as active citizenship, institutional transparency, and public trust, which are essential for strengthening democratic engagement and improving the quality of collective life (Queirós et al., 2022).

However, despite these advances, the concept remains theoretically fragmented and analytically underdeveloped. Much of the existing literature has yet to converge on a clear and consistent definition of the Knowledge Society, and proposed measurement frameworks often lack solid theoretical foundations or fail to reflect current challenges. This paper seeks to address these shortcomings by offering a comprehensive and coherent definition of the Knowledge Society, through revisiting the metrics employed to assess its development and by analysing the productive mechanisms through which knowledge contributes to economic growth. Thus, the first aim of this article is to examine conceptualisations of the Knowledge Society and propose an unambiguous definition that outlines its main characteristics, evolution, driving factors, limitations, and challenges.

Another essential contribution of this work involves the revision of the current indicators that measure progress towards a true Knowledge Society based on a comprehensive review of the academic literature. UNESCO, in its report Towards Knowledge Societies (Bindé, 2005), proposes key dimensions, such as quality education for all, freedom of expression, universal access to information, and cultural diversity. Similarly, the World Bank Institute (Chen & Dahlman, 2006) developed the Knowledge Assessment Methodology (KAM) which assesses factors such as innovation systems, skilled workers, information technology infrastructure, and the institutional environment. An updated version of this metric was developed in the Knowledge Economy Index (European Bank for Reconstruction & Development, 2019). Thus, following the work of Oxley et al. (2008), which stresses the necessity for a sound theoretical backing and the proposal of indicators measuring the Knowledge Society, the second objective of this work is to assess the indicators proposed by the UNESCO, based on the definition of the Knowledge Society developed in this paper.

The third purpose of this study is to examine the role of knowledge as a central catalyst for economic development. Carlsson et al. (2009) investigated the connections between knowledge generation, entrepreneurship, and economic expansion in the United States over the last 150 years. Their research drew a clear distinction between general knowledge and knowledge with direct economic relevance, and analysed how these forms have evolved over time. These authors pointed out the applied orientation of research and development in the United States, and highlighted the continuous collaboration between universities and the business sector. They also assessed the substantial increase in R&D investment during and after the Second World War, and explained how these resources were gradually converted into economic activity, initially through established corporations and, in recent decades, increasingly through innovative new ventures.

After defining the Knowledge Society and its connection to the productive structure, this study examines the mechanisms that enable economic growth through transformations in the productive structure, while exploring ways to promote these mechanisms and evaluating their limitations.

Hence, this article seeks to address several key research questions that underpin the conceptual and analytical clarification of the Knowledge Society. The following research questions are posed in order to analyse the implications of knowledge and the Knowledge Society in the productive system, its evolution, and its limits, and to propose several metrics for its assessment:

- •

RQ1: What is knowledge from an economic perspective?

- •

RQ2: What is the Knowledge Society, and what are the characteristics that define it?

- •

RQ3: How can advances be made in the Knowledge Society and what are the metrics to measure them?

- •

RQ4: What are the limits of the Knowledge Society?

By addressing these questions, the article makes a threefold contribution. First, it offers a clear and comprehensive definition of the Knowledge Society, grounded in an extensive review of the existing literature. Second, it critically assesses the adequacy and relevance of current measurement frameworks, particularly those proposed by international organisations such as UNESCO and the World Bank. Third, it examines the mechanisms through which knowledge acts as a catalyst for structural economic transformation and growth.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows. Section 2 offers a comprehensive review of the literature, traces the evolution of the concept, and proposes a theoretically grounded definition. Section 3 develops a measurement framework based on key indicators of knowledge production and innovation. Section 4 presents empirical evidence to assess the progress of selected countries towards a Knowledge Society. Section 5 discusses the broader implications of these findings and reflects on the limitations and contradictions inherent in the concept. Lastly, Section 6 concludes with a synthesis of the main insights, and outlines directions for future research.

Literature reviewConceptualisations of the knowledge society in recent decadesThe concept of the Knowledge Society has been analysed from various perspectives since its early conceptualisation by Peter Drucker in the 1960s (Drucker, 1969). In the 1970s, Bell (1973) further refined this idea with his concept of the post-industrial society, and emphasised the shift from manufacturing to services and the increasing role of intellectual work. The perception that the structure of production has undergone profound changes in the last century has been highlighted in many articles and books, and has received various names. Piore and Sabel (1984) defined this change as “the second industrial revolution”, Tofller (1981) used the term “third wave”, while Drucker (1993) called it “post-capitalism”. The latter author introduced the idea of a post-industrial society where knowledge, rather than land, labour, and capital, would become the primary driver of economic growth and social development. This marked a departure from traditional economic paradigms, by positioning knowledge as both a productive asset and a source of competitive advantage. Previously and similarly, Machlup (1962) defined the term knowledge production, which, in the Knowledge Society, includes the combination of both production and distribution of knowledge. This author was the first to propose a measure for evaluating how advanced a country is in utilising knowledge as a production asset.

The Knowledge Society also extends to the social and cultural dimensions of knowledge. Hordern posits that knowledge is not merely an abstract concept but is deeply embedded in social practices and relationships (2021). This perspective highlights the importance of inclusive and participatory practices in knowledge creation, and ensures that knowledge is accessible and meaningful to all members of society. The emphasis on social constructionism further reinforces the idea that knowledge is shaped by the interactions and experiences of individuals within their cultural contexts (Burr, 2015).

In addition to the economic and social dimensions, the role of technology in shaping a Knowledge Society cannot be overstated. Castells (1996, 1998) provided a comprehensive framework with his network society thesis. Castells argued that the transformation of societies not only involved the rise of knowledge-based economies but also involved the way knowledge was structured, distributed, and leveraged through global digital infrastructures. His work highlighted the role of IT in reshaping economic, social, and political systems, with an emphasis on the growing importance of interconnected networks of knowledge.

Building on these earlier perspectives, Stehr (1994, 2001) introduced a more sociological and political interpretation of the Knowledge Society. Knowledge had become the most significant force shaping modern society, not only in economic terms but also in other spheres, such as culture and politics. He argued that the increasing role of scientific knowledge and expertise in governance and decision-making had led to a society where the production, dissemination, and application of knowledge determined power structures. Unlike Castells, who focused on the technological and structural aspects of knowledge diffusion, Stehr emphasised the epistemic dimensions and the implications of knowledge as a form of governance. However, the governance of knowledge within a society is a multifaceted issue that requires collaboration across various sectors. Clarke and Clarke (2009) emphasised the necessity for educational systems in this governance, where IT and global connectivity were seen as reshaping the landscape of learning and professional development.

Maasen and Winterhager (2001) argued that the interplay between science and society is critical in understanding the complexities of knowledge production in contemporary settings. This relationship necessitates ongoing reflection and engagement with the ethical dimensions of knowledge, especially regarding the challenges posed by globalisation and the rapid pace of technological change. Today, discussions on the Knowledge Society are increasingly linked to artificial intelligence, automation, and the ethics of knowledge production (Brynjolfsson & McAfee, 2014).

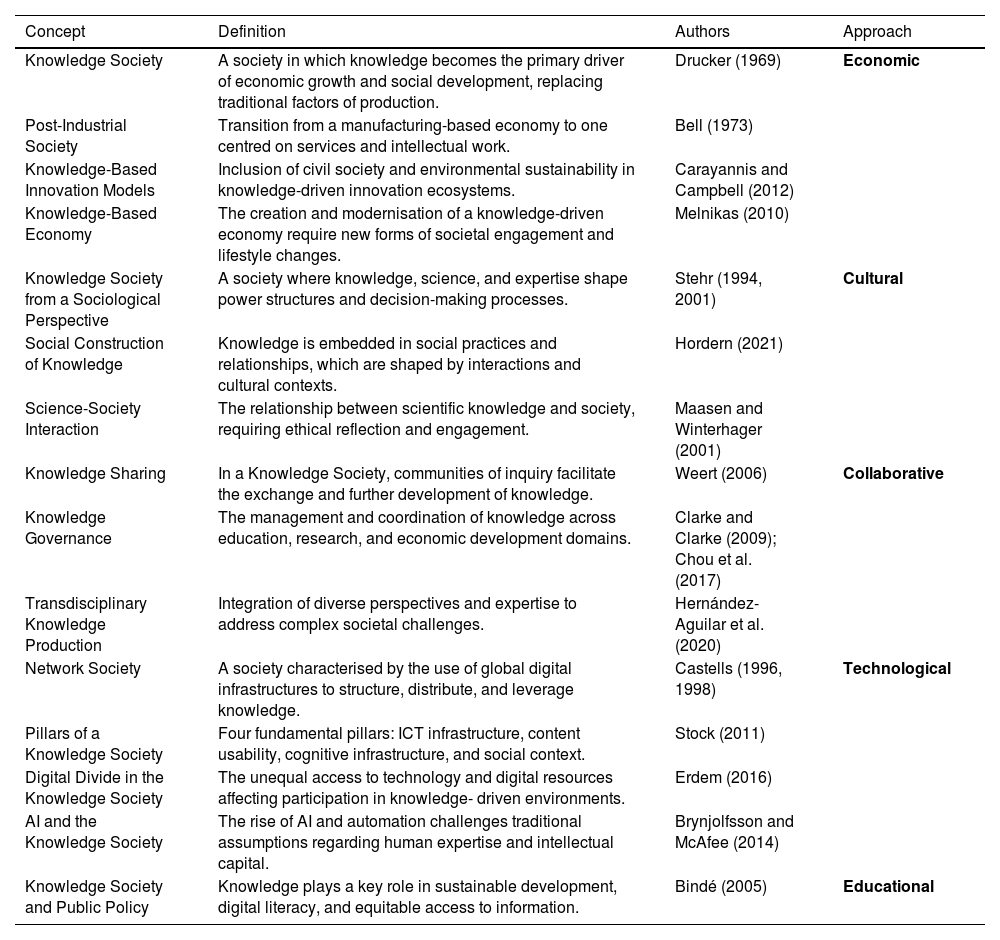

Therefore, the definition of the Knowledge Society encompasses a multifaceted understanding of the role of knowledge in shaping economic, cultural, technological, sociological, political, educational, and ethical landscapes (see Table 1).

Definitions of the Knowledge Society and related concepts.

| Concept | Definition | Authors | Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Society | A society in which knowledge becomes the primary driver of economic growth and social development, replacing traditional factors of production. | Drucker (1969) | Economic |

| Post-Industrial Society | Transition from a manufacturing-based economy to one centred on services and intellectual work. | Bell (1973) | |

| Knowledge-Based Innovation Models | Inclusion of civil society and environmental sustainability in knowledge-driven innovation ecosystems. | Carayannis and Campbell (2012) | |

| Knowledge-Based Economy | The creation and modernisation of a knowledge-driven economy require new forms of societal engagement and lifestyle changes. | Melnikas (2010) | |

| Knowledge Society from a Sociological Perspective | A society where knowledge, science, and expertise shape power structures and decision-making processes. | Stehr (1994, 2001) | Cultural |

| Social Construction of Knowledge | Knowledge is embedded in social practices and relationships, which are shaped by interactions and cultural contexts. | Hordern (2021) | |

| Science-Society Interaction | The relationship between scientific knowledge and society, requiring ethical reflection and engagement. | Maasen and Winterhager (2001) | |

| Knowledge Sharing | In a Knowledge Society, communities of inquiry facilitate the exchange and further development of knowledge. | Weert (2006) | Collaborative |

| Knowledge Governance | The management and coordination of knowledge across education, research, and economic development domains. | Clarke and Clarke (2009); Chou et al. (2017) | |

| Transdisciplinary Knowledge Production | Integration of diverse perspectives and expertise to address complex societal challenges. | Hernández- Aguilar et al. (2020) | |

| Network Society | A society characterised by the use of global digital infrastructures to structure, distribute, and leverage knowledge. | Castells (1996, 1998) | Technological |

| Pillars of a Knowledge Society | Four fundamental pillars: ICT infrastructure, content usability, cognitive infrastructure, and social context. | Stock (2011) | |

| Digital Divide in the Knowledge Society | The unequal access to technology and digital resources affecting participation in knowledge- driven environments. | Erdem (2016) | |

| AI and the Knowledge Society | The rise of AI and automation challenges traditional assumptions regarding human expertise and intellectual capital. | Brynjolfsson and McAfee (2014) | |

| Knowledge Society and Public Policy | Knowledge plays a key role in sustainable development, digital literacy, and equitable access to information. | Bindé (2005) | Educational |

Together, these approaches encompass a broad spectrum of theoretical and empirical perspectives, each contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of how knowledge shapes economic, social, and technological transformations.

In recent years, new contributions have revisited the concept of the Knowledge Society from a contemporary standpoint, by addressing the rise of digital competence, the role of intellectual capital, and the transformation of educational systems. Zhao et al. (2021) emphasise the importance of fostering such competences within universities to adapt teaching and learning to digital ecosystems. At the same time, Ibarra-Cisneros et al. (2023) reaffirm the strategic role of intellectual capital in organisational development and innovation, and it directly to the socio-economic dynamics of the Knowledge Society. These contributions highlight the need for renewed conceptual and methodological tools capable of capturing the complexity of knowledge production, circulation, and application in today’s digitally mediated and institutionally evolving landscape.

This dispersion of approaches certainly enriches the debate and provides a holistic vision of the problem with multiple details and ramifications. Nevertheless, Oxley et al. (2008) observed that the Knowledge Society appears to have as many definitions as there are authors included in its discussion. Thus, the first step involves defining the concept of knowledge from an exclusively economic perspective (the origin of the term Knowledge Society) and building the rest of the work upon this narrow definition.

Definition of knowledge from an economic perspectiveWith great insight, Drucker (1969) emphasised that the concept of knowledge before the industrial revolution focused on “self-knowledge, that is the intellectual, moral, and spiritual growth of the person” and that technical knowledge referred to named skills. It was after 1700 in the Western World that technology gained its place in the schools and universities as a combination of skills (techné) with logy, that is, as organised, systematic, purposeful knowledge. This constitutes the foundation of our study: the Knowledge Society is based on the development of technical knowledge and its application to productive systems. As early as 1973, Bell described “the post-industrial society as a Knowledge Society, since the sources of innovation are increasingly derivative from research and development (and more directly, there is a new relationship between science and technology due to the centrality of theoretical knowledge)” (Bell, 1973, p. 212).

The dichotomy between technical knowledge and ethical and moral knowledge must be addressed before the Knowledge Society can be studied in depth. People are acting beings (Mises, 1949), and acting presupposes ends and means. Human beings choose means logically to obtain specific objectives. This duality splits knowledge into two categories. One is directly related to the choice of ends (moral, ethical, religious, and even aesthetic fields), where logic is the dominant tool. The other category is related to the means (logical, technical, and scientific knowledge). The reduction of knowledge to exclusively scientific and technological knowledge forms the mainstream in the studies of the Knowledge Society, as pointed out by Stehr (1994, 97–103), who commented that the reason for the concept was specifically scientific knowledge. No disregard for non-technical knowledge is intended in this statement: quite the contrary. Ultimate ends (religious, ethical, and moral) are what determine the course of action of human beings, and they use technical knowledge to achieve those ends. However, the concept of the Knowledge Society is linked to the development of the resources available to human beings, for better or for worse. Despite a prevalence in society to consider scientific knowledge as the causal relationship in natural sciences, this scientific knowledge also encompasses the praxeological knowledge of social sciences (Hoppe, 2007), such as political science, economics, and jurisprudence.

Definition of knowledge societyThe conceptualisation of knowledge as presented above is found in the International Encyclopaedia of the Social Sciences that defines the Knowledge Society as one where “knowledge assets (also called intellectual capital) are the most powerful producer of wealth, sidelining the importance of land, the volume of labour, and physical or financial capital" (Vesely, 2008, p. 283). As in our proposal of knowledge, this definition considers knowledge as linked to producers (knowledge assets) and wealth. The basic characteristics are present in this definition, but it has problems in establishing the frontier. With this definition, the threshold of when a specific society can be considered a Knowledge Society cannot be established. First, across the ages, knowledge has provided the basis for production and improvement. Without knowledge on navigation, mining, livestock, agriculture, medicine, etc., no civilization would have arisen. Second, better knowledge can enable activities to be performed with fewer resources (e.g., productivity of land in agriculture with better crop varieties, insecticides and fertilisers), although the importance of land, capital goods, and labour does not diminish. The resources can differ or be in varying proportions and quantities, but resources are always available.

A second relevant definition for this study is that of UNESCO's World Report (Bindé, 2005) that describes Knowledge Societies as those that generate, share, and make knowledge that may be used to improve the human condition available to all members of the society.. In this definition, the aim is also the improvement of human condition, but the focus is on the generation of knowledge. Again, the problem is a matter of establishing a threshold, but the speed of knowledge generation in a society can be taken as the measurable main characteristic of a Knowledge Society. Therefore, we conceptualise the Knowledge Society as a society that invests a considerable portion of its material and human resources in the generation of scientific knowledge in order to increase the innovative capacity of both the productive system and social structures to improve human life.

Despite the inclusion of the innovations in social structures in our definition, in the rest of the paper our focus is exclusively on innovations in the productive system. This rejection is not a pragmatic decision nor one that facilitates the measurement of the Knowledge Society, but rather stems from deeper causes. In very complex systems such as social structures, only the evolutionary advances based on trial and error (acceptance and rejection) of a multitude of innovations made by individuals (spontaneous orders) are prone to success. In fields such as economics, jurisprudence and political sciences, the creation of knowledge is slow and painstaking, based on logic deductions on the resulting systems. As Hayek (1989, 102) postulates, “the operation of the money and credit structure has, however, with language and morals, been one of the spontaneous orders most resistant to efforts at adequate theoretical explanation, and it remains the object of serious disagreement among specialists”. The breakthroughs in knowledge in these fields remain very scarce and difficult to attain and, as Mises (1949, 869) points out for economics, “there never lived at the same time more than a score of men whose work contributed anything essential to economics”. In the natural sciences and technology, specialisation and incremental discoveries are much more frequent and usual, and the validity of the discovery can be more easily contrasted.

Another major question is also included in UNESCO's definition of the Knowledge Society (Bindé, 2005) and it refers to the idea that not only should knowledge creation be considered, but also its exchange, storage, and retrieval. In our definition, the emphasis is on knowledge creation, but this knowledge must be made available. The development of IT with its ability to store, process, and communicate data has been of great help to the scientific community and to the creation of knowledge, but IT alone has brought about the apparition of the Information Society (Webster, 2014). The Knowledge Society and Information Society influence each other and overlap, but they are clearly different phenomena. Information technology deals with data instead of knowledge. Knowledge is a mental model of how the world works, often expressed in terms of formulae and rules. Knowledge establishes which data is relevant for the resolution of a specific problem and how to process such data in order to attain the information required for the decision to be made. Thus, knowledge defines what information is, and not the other way around. This is a major conclusion for this work since although IT is a fundamental tool for knowledge diffusion, for its creation the main actors are humans, and the role of IT is relevant but always subordinated and dependent on the researchers’ direction and vision. The focus of our definition is on knowledge creation, its crystallisation in innovations, and the technology frontier. This approach differs considerably from that of Machlup (1962), who considers not only creation but also diffusion.

In our definition, knowledge is first and foremost an asset for productive agents: a unique, non-rival resource that does not depreciate and whose value increases through use and sharing. From this perspective, the Knowledge Society is the result not only of macro-level developments, such as digital infrastructures and national innovation policies, but also of the specific ways in which knowledge is generated, organised, and applied within organisations. It is precisely at this micro level where knowledge becomes actionable: where it informs strategic decisions, supports innovation, and creates value. Firms play a central role in this dynamic, since they provide the environments in which knowledge is continuously produced, refined, and operationalised. Understanding how this occurs requires a closer look at the mechanisms, practices, and conditions that govern knowledge flows within organisations. These questions lie at the core of what is commonly known as Knowledge Management (KM): a field whose role within the broader context of the Knowledge Society deserves closer examination.

The role of knowledge management in the knowledge societyDrucker's definition, "A society in which knowledge becomes the primary driver of economic growth and social development, replacing traditional factors of production", highlights a trend in production systems but also poses a limitation in measuring the evolution towards the Knowledge Society. First, in every era and production system, knowledge plays a fundamental role and remains key to growth. Growth due to the invention of the plough may have been more significant than growth due to many of today's more sophisticated systems. What is evident, however, is the accumulation of knowledge throughout history, which requires a combination of highly qualified and specialised personnel to create, operate, and improve most current systems. Two relevant phenomena emerge for companies. First, the velocity of knowledge creation forces companies to absorb and integrate new knowledge within their specific field of activities. Second, the vast amount of knowledge in any field necessitates the specialisation of knowledge workers in specific areas and the creation of multidisciplinary teams to manage innovations. Together, these two phenomena have fostered the boom of KM.

Knowledge Management is the process that enables the optimisation of a company’s intangible assets. For Wiig (1997), knowledge creation lies at the core of organisational learning, since it serves as the mechanism through which employees acquire knowledge and are motivated to generate new insights, thereby ultimately enhancing a company’s competitiveness (Curado, 2008; Andreeva & Kianto, 2011; Bushra et al., 2017).

Before the rise of KM in the 1990s as a formalised field, knowledge in organisations was primarily tacit and passed along through personal experience and informal networks. Companies relied on individual expertise, and there was little formal strategy for capturing or managing knowledge. The management of knowledge was often isolated, and there was no widespread understanding of its strategic value. During the 1990s, however, KM became recognised as a critical component for organisational success. Knowledge began to be recognised not as an individual asset but as an organisational resource. Companies began to establish formal KM strategies and infrastructure, which focused on knowledge capture, storage, and dissemination. This period saw the development of systems for managing both tacit (informal, experiential) and explicit (documented, codified) knowledge. Technologies such as databases, intranets, and document management systems were introduced to aid in the formalisation of knowledge processes.

In the 2000s, KM became central to fostering innovation, since it enabled teams to collaborate more effectively and to harness collective knowledge for problem-solving. Innovations, such as open-source software and crowdsourcing, also contributed to this shift, and led to models for innovation of a more decentralised and collaborative nature. In recent years, KM has evolved towards a more strategic and dynamic process. The focus has shifted towards the creation of a knowledge-centric culture where continuous learning, adaptability, and cross-functional collaboration are key factors. The aim is to develop a firm's internal knowledge management capabilities as a disruptive factor in its innovation potential (Santoro et al., 2018). Several studies focus on knowledge collaborations between firms, giving rise to a distinct research strand on KM and open innovation, as highlighted by Randhawa et al. (2017) and Simeone et al. (2017).

This increasing interest in KM by firms shows the increment of the rate of creation of knowledge by society (not only by companies, but also by other institutions, such as universities and public research centres). The crux of the matter now involves how to measure the speed of creation of productive knowledge and its variation over recent decades, and to ascertain what impact it exerts on growth. This internal view of knowledge creation within firms is paramount in the Knowledge Society. The understanding of a relationship between knowledge creation and innovation performance, and the assessment of such a relationship is essential in the Knowledge Society (Cabrilo et al., 2024). Furthermore, there are other research areas profoundly linked to the Knowledge Society, such as the collaboration between firms to integrate the knowledge needed for complex innovations (Shan et al., 2023) and the emergence of knowledge ecosystems derived from the trend towards specialisation (Chen et al., 2024).

Measuring the knowledge societyDespite the growing importance of the Knowledge Society as a framework for understanding contemporary social, economic, and educational transformations, there is still no consensus on the key parameters that define it. While it is widely admitted that a Knowledge Society is characterised by the central role of knowledge as a fundamental resource, with its production, dissemination, and application being essential to societal functioning and development, there is no agreement on how to precisely identify these elements, nor on the most appropriate methods for quantifying this concept in practical contexts.

Today, the most relevant set of indicators to measure the Knowledge Society include the Global Innovation Index (GII), Global Knowledge Index (GKI), European Innovation Scoreboard (EIS), and the Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI). After having analysed these indicators, Katuščáková et al. (2023) concluded that there is significant variability in how the Knowledge Society is measured. Nevertheless, they managed to identify the key pillars that can be considered the foundation of the KS. These include factors such as IT levels, R&D, human resources, innovation, patents, and education. Previously, in a theoretical work, Stock (2011) had identified four pillars that underpin a Knowledge Society: IT infrastructure, content usability, cognitive infrastructure, and the social context in which knowledge is produced and consumed. Furthermore, Carter (2009) revealed that measuring knowledge-based economy performance requires comprehensive indicators that reflect innovation, human capital, and technological infrastructure.

Following these approaches, the Knowledge Assessment Methodology (a framework designed to evaluate the state of knowledge within an organisation or a country, particularly in terms of its capacity to generate, distribute, and apply knowledge for economic and social development) focuses on key areas such as human capital, innovation systems, information and communication technologies, and education.

In our conceptualisation of the Knowledge Society, several of the aforementioned dimensions do indeed fit. First, education is clearly a service provided to a final consumer, and it implies no kind of knowledge creation. Certainly, in a highly specialised society, knowledge creation implies years of formation, and the number of PhD students can provide an indirect proxy to measure the percentage of the population dedicated to research. In a highly specialised society, however, a high percentage of human resources in any sector (primary, secondary, and tertiary) must also have higher studies. Second, IT, as mentioned in Section 2.3., supports the development of knowledge, and serves primarily as a tool for researchers, who constitute the main actors of the Knowledge Society. IT plays a major role in the diffusion and access to knowledge, but the presence of a robust IT infrastructure does not necessarily indicate the development of the quaternary sector, since IT is intensively used in other sectors of the economy as well. For this reason, IT infrastructure presents an indirect unreliable proxy for measuring the Knowledge Society. Therefore, our indicators are drawn exclusively from human capital dedicated to research activities and the development level of innovation and research systems. Nevertheless, the dissemination of knowledge remains a key element in the Knowledge Society, and interesting initiatives to measure the dissemination of knowledge would help to gauge the whole cycle of knowledge (Cen et al., 2023).

We propose two types of indicators: those based on results, and those based on the key factors of knowledge creation. For the innovation and research output, two measurement indicators are proposed: the number of high-impact papers published in scientific journals as a metric for knowledge creation (considering both the frequency of publications in peer-reviewed journals and the citations they receive); and the number of patent applications as an innovation metric.

For the key factors of knowledge creation, two indicators are proposed: the number of knowledge workers and professionals in terms of the proportion of the workforce engaged in knowledge- intensive jobs, such as research and technology development; and R&D expenditure as a percentage of GDP, whereby high levels of research and development investment are indicative of a Knowledge Society.

Data samplesPatent application data per country was retrieved from the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO), from the WIPO IP Statistics Data Center (WIPO, n.d.) covering the period from 2001 to 2021. To allow for cross-country comparisons, the number of patent applications was normalised regarding population size: the count was divided by the respective national population. This normalisation generated a standardised estimate of recent patent activity across countries.

The population size per country was obtained from the United Nations (UN) and the World Bank for the time period 1981 to 2023.

Data on personnel dedicated to R&D was retrieved from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) through the OECD Data Explorer (OECD, n.d.). The OECD sourced the original data from the UN; however, direct access to sector-specific R&D personnel data was only available through the OECD. The dataset includes full-time equivalent (FTE) figures: for instance, if a university lecturer allocates 30 % of their time to research, this is counted as 0.3 FTE. The data covered the year 2019 and was collected in accordance with the Frascati manual (UNESCO, 2014), which provides international guidelines for R&D statistics.

Information was disaggregated into sectors of performance, which included the business sector, government sector, higher education sector, and private non-profit sector.

For the aforementioned normalisations based on population, data corresponding to a single year was obtained from the UN Population Division Data Portal (UN, n.d.), specifically using population figures as of July 2019. All indicators were retrieved for the year 2019, with the exception of academic publication data, which was collected for the year 2020, in acknowledgement to the typical delay in the publication process. The year 2019 was selected as the reference point since it represents the most recent period prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, thereby minimising potential distortions associated with the global health crisis.

For analyses covering longer time periods, data was retrieved from the World Bank’s Open Data Portal, since this source provides information for earlier years of a more consistent and reliable nature.

Data pertaining to the gross expenditure on R&D (GERD) was obtained from the OECD through the OECD Data Explorer (OECD, n.d.). The dataset included GERD as a percentage of GDP and, where available, included the average expenditure spanning the years 1981 to 2023 (e.g., data for China was available only from 1991 onwards). Expenditure data was also disaggregated into the same four research sectors previously identified for R&D personnel, and was accessible through the same OECD Data Explorer platform.

Several limitations were identified in the dataset. As previously noted, data was missing for certain years and countries, resulting in uneven temporal coverage. Furthermore, although the information was sourced from reputable institutions such as the OECD and the World Bank, the methods of data collection and reporting vary significantly across countries and, in certain cases, even across regions within the same country. These differences may reflect divergent statistical capacities, definitions, and/or institutional practices. Furthermore, for several countries and years, figures were not based on direct measurements but rather on estimates or modelled data. As such, caution is warranted when interpreting cross-national comparisons and long-term trends, particularly in cases where data reliability and consistency may be compromised.

A query was constructed within the Web of Science (WoS) platform to retrieve relevant scientific publications. The search was conducted across all available records and subsequently refined using the following criteria: publications had to be included in the WoS Core Collection, classified by WoS as “highly cited,” and published in the year 2020. The resulting dataset was exported to the Bibliometrix package within the R statistical environment for further analysis. For each publication, the affiliation of the corresponding author was employed to determine the country of origin. The total number of highly cited publications was then aggregated per country and normalised using the respective population figures for the year 2019.

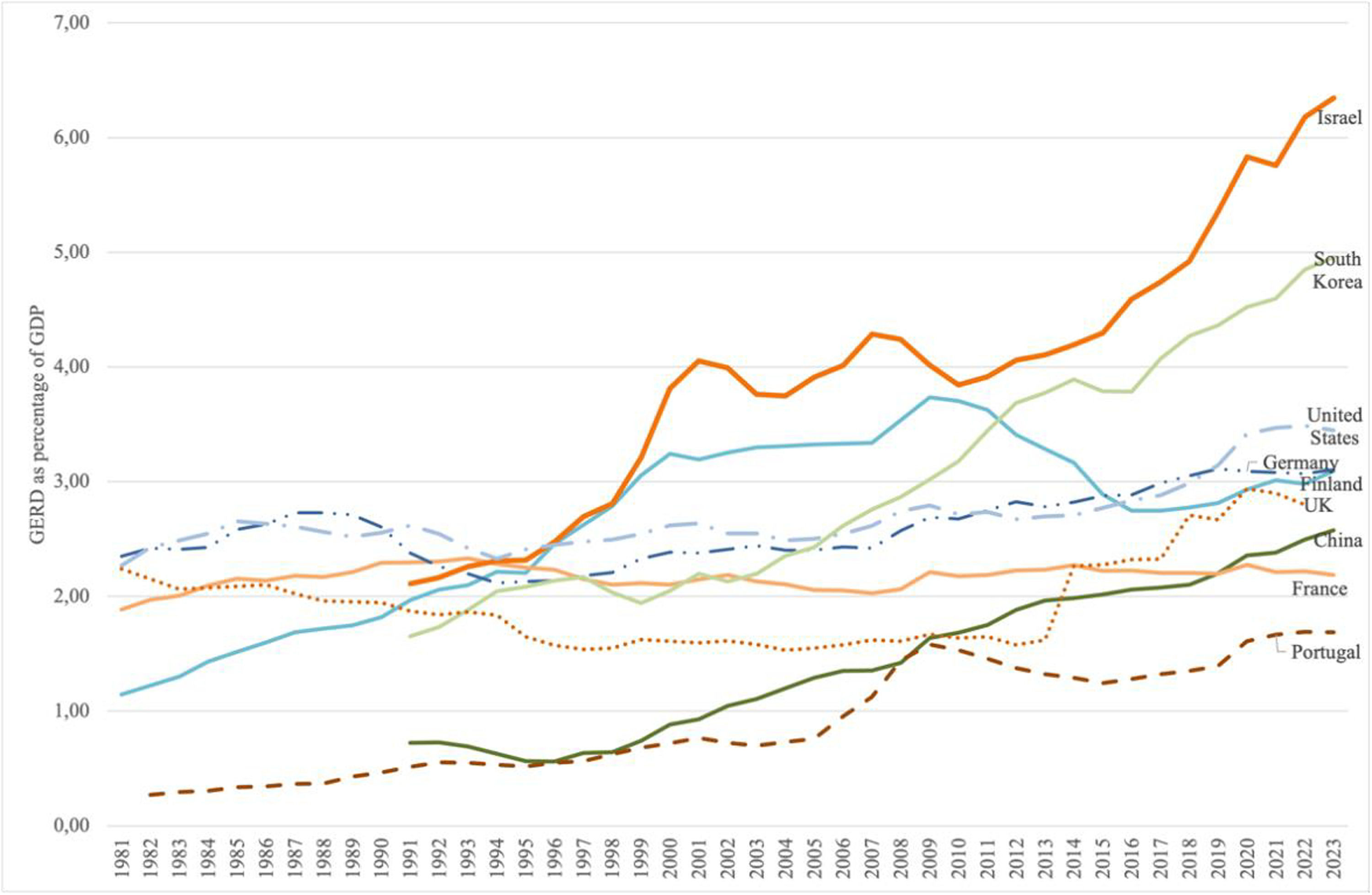

Evolution and situation of the knowledge societyInvestment in R&D has grown in most countries in recent decades. Fig. 1 shows GERD as a percentage of each country’s GDP. Information is shown for the period 1981 until 2023, and, in order to prevent cluttering, only nine of the most developed countries are shown in the figure. Israel is the country with the highest GERD/GDP, followed by others such as South Korea and the United States of America. Portugal and France can be observed in the lower part of Fig. 1, despite having improved their GERD spending over the years.

The United States of America is the country with the highest absolute GERD, though smaller countries such as Israel and South Korea achieve a higher relative value when GERD is divided by GDP. China also has a high GERD absolute value, which has grown steadily over the last thirty years, up to the current value of 2.5 % GERD/GDP.

An interesting result of the graphic is the slow but steady increase in investment in R&D per capita. Nevertheless, this is not a given tendency for all countries. Several countries, such as Israel, South Korea, and China, have been able to grow considerably in the last three decades. Conversely, a number of countries have experienced negative fluctuations, as in Finland, where a steep decline occurred in the aftermath of the 2008 global economic crisis. This pattern is also apparent in other countries, which typically have lower GERD/GDP ratios.

Countries lacking data for the majority of key variables were excluded from the analysis. To be considered eligible, a country was required to have data available for at least three of the following variables: gross expenditure on R&D (GERD), GDP per capita, number of patent applications, full-time equivalent researchers in total, and full-time equivalent researchers in the business sector.

Following this initial filtering, Luxembourg was excluded due to its small population size and exceptionally high GDP per capita, which significantly distorted comparative analyses. Moreover, data from Israel was excluded for patent comparison, since recent changes in the country’s patenting strategy have led to a marked decline in patent applications in recent years, thereby limiting its comparability with other countries.

Fig. 2 shows the relationship between R&D full-time employees and number of patent applications per country. It is interesting to note that the distribution of the relationship suggests a non-linear relationship (e.g., the higher the number of R&D employees, the higher the number of patents). However, above a certain threshold number of personnel dedicated to R&D, the number of applications for patents stalls. Japan, South Korea, and Switzerland are among the countries that dedicate most personnel to R&D. However, the number of patents is very similar to that of Germany, Denmark, and others that have approximately half the people dedicated to R&D . The number of employees relative to the population appears in Fig. 3 in a stacked distribution of their R&D personnel across the Business enterprise sector (blue bar), the Government sector (red bar), the Higher education sector (green bar), and the Private non-profit sector (purple bar). As can be observed, the countries with the highest number of full-time equivalent R&D personnel relative to the population are Denmark, Israel, Finland, and Switzerland. Interestingly, China has a low full-time employee rate.

Finland could be selected as a success case across all data. With a balanced GERD/GDP ratio and a ratio of R&D full-time employees only slightly higher than that of the USA, Finland has one of the highest patent applications rates. Both the GERD/GDP and the relationship with patent applications are shown in Fig. 4.

The importance of the quaternary sector (the knowledge-creating sector) in any society can be measured in terms of money and in terms of human resources. It is therefore important to consider the evolution of R&D personnel as a percentage of the total population. Fig. 2 shows this evolution per country. The number of R&D personnel was gathered as the full-time equivalent from the OECD Data Explorer. R&D personnel for each country and year was then normalised by the corresponding population (per thousand). Population data was obtained from the World Bank database (World Bank, n.d.), based on the de facto definition, which counts all residents regardless of legal status or citizenship 1and uses midyear estimates. Fig. 2 shows clear growth in R&D personnel in developed countries, with a more abrupt growth trend than that observed in the GERD/GDP ratio. The country distribution is similar in Figs. 1 and 2, although for certain countries (e.g., China), the percentage of R&D personnel clearly lags behind its GERD/GDP ratio.

One important issue to study involves the resources provided by government and private initiatives. For the GERD/GDP ratio, no data is available. In the case of personnel, Fig. 3 shows the distribution of R&D personnel in business, government, higher education, and private non-profit sectors. Fig. 3 illustrates a clear dominance of the private sector in knowledge creation efforts, except in certain countries, such as Greece, Russia, Lithuania, Latvia, the Slovak Republic, and Argentina (taking into account that the majority of universities in these countries are public).

Efficiency of knowledge creationIt is clear that the allocated resources to knowledge creation (R&D) per country have consistently grown, both in public and private spheres. But how is this effort reflected in knowledge creation? The first objective measure of knowledge creation proposed (patents) is dominated by private initiatives. Fig. 4 shows the effect of GERD/GDP on patents per country. The relationship exhibits a sigmoid shape, with exponential growth in results for countries with a GERD/GDP ratio between 2 % and 4 %. This rapid growth appears to stabilise at approximately 5 % GERD/GDP.

When only the patents registered by higher education institutions (universities) per country are considered, as shown in Fig. 5, the results exhibit moderate and linear growth. Higher university expenditure translates into a higher number of patents per capita. Nevertheless, several cases show a clear positive differentiated behaviour (Japan, Switzerland, and South Korea), which highlights the role of national policies on the funding and organisation of universities in explaining these differences.

Regarding the relationship between patents and R&D personnel (per thousand capita) per country, as shown in Fig. 6, the results also exhibit exponential growth, with notable exceptions, such as Switzerland and Japan. These two countries show impressive results in patents, an effect that is also evident in Fig. 5. The effective functioning of universities in these countries largely accounts for this difference.

The second measure proposed for measuring the results of the Knowledge Society is that of academic production per country, as indicated by the papers of the WoS Core Collection classified as “highly cited” in the year 2020. When comparing this academic production with the GERD/GDP ratio, the results show no clear pattern. This is because academic production is closely linked to research conducted by higher education institutions. For R&D investment and personnel that are split between public and private sectors, Figs. 7 and 8 clearly show the dominance of universities in academic production, with a generally linear relationship for most countries. The outstanding results of Switzerland could be explained to a great extent by the effect of it being the country with the highest concentration of the most relevant journals.

On the other hand, private R&D expenditure fails to reveal a clear pattern in academic results, as shown in Fig. 9.

DiscussionAlthough the concept of a Knowledge Society is widely acknowledged for its significance in shaping modern economies and education systems, there remains a lack of consensus on how to define and measure this concept. This reflects the complexity and multidimensional nature of knowledge as both a resource and a social construct. Thus, there is no single metric or universal definition capable of capturing its full scope. As Erdem (2016) notes, a Knowledge Society necessitates a shift in educational paradigms that leads to a more personalised and continuous learning experience, which is essential for individuals to thrive in such an environment.

While GERD is often considered a central indicator of a country’s commitment to innovation and technological advancement, its role as a proxy for the Knowledge Society demands a more nuanced discussion. At first glance, sustained increases in GERD (such as those observed in Israel and South Korea, see Fig. 1) suggest a linear progression toward a knowledge-creating society. However, the interpretation of this indicator in isolation risks overlooking the qualitative dimensions of how knowledge is produced, diffused, and integrated into the broader societal fabric.

Nevertheless, the temporal consistency of GERD levels in countries such as the United States, Germany, and the UK further illustrates that a sustained and increasing investment in knowledge creation by developed countries remains a clear trend. An interesting result emerges when Fig. 1 (investment in R&D) is compared to Fig. 2 (investment in knowledge-creating personnel). Although the upward trends over the last four decades are similar, the significant investment made by China is not reflected in the number of full-time personnel, which indicates that the formation of researchers depends not only on economic effort but also on the culture and broader economic conditions of the country.

Another widely used proxy for assessing the advancement of Knowledge Societies is that of patent activity. Yet, as with GERD, interpreting patent data in isolation presents major limitations. Patents offer standardised and comparable information, but they only partially capture innovation dynamics. The findings shown in Fig. 4 indicate that, in certain cases, patent intensity does not align closely with GERD levels, which highlights the need to consider additional indicators when assessing knowledge intensity. As Petralia et al. (2017) argue, countries move up the technological ladder through varied paths, many of which are not captured by patent metrics.

The representation of GERD/GDP versus patents per capita (Fig. 4) shows a clear exponential relationship and establishes the threshold of 2 % GERD/GDP as the critical point for investment returns to be obtained in terms of patent numbers. Nevertheless, as with nearly all natural or social phenomena, knowledge creation tends to stabilise beyond a certain point (law of diminishing marginal returns), producing the sigmoid curve observed. An exceptional case in Fig. 4 is presented by Israel. The low patents-to-GERD rate can be explained by the fact that most of Israel’s R&D effort is driven by the defence and high-tech sectors, with little interest in making the technology public through patents. Other countries, such as Spain or Italy, with relatively large public R&D sectors, show weaker patenting outcomes, often due to an academic bias more oriented toward publications than commercialisation.

The representation of patents versus R&D personnel, both per capita per country (Fig. 6), also shows an exponential relationship, although there are exceptions with outstanding performance, such as Switzerland and Japan, which reflect the need for a complex ecosystem in knowledge creation.

On the other hand, high-impact academic production, in terms of papers published, is only correlated with public effort, both in investment and personnel. The lack of any relationship between academic production and private-sector effort may be attributed to the limited incentives for private firms to publicise research results. Nevertheless, the role of academic production should not be underestimated. Weert (2006) underscores that knowledge sharing is a fundamental characteristic of such societies, where communities of inquiry facilitate the exchange and further development of knowledge. In this regard, higher education institutions are not only centres of knowledge dissemination but also key actors in co-creating knowledge with societal relevance. Their contributions, through scientific publications, collaboration with industry, and knowledge transfer mechanisms, should be fully integrated into any framework assessing the advancement of a Knowledge Society (Queirós et al., 2022).

High levels of R&D investment or of patent output may reflect technological dynamism, with evident productivity growth and better products and service when they materialise in investments in the industry. However, these improvements do not necessarily imply economic growth or improvements in sustainability when certain other factors are not present. The advances in technology may be offset by a loss of net capital or by massive bad investment by entrepreneurs, thereby producing a net low growth. At the same time, the capacity of investment in R&D depends on the GDP per capita, and not on growth. This double relationship implies that there is no clear pattern between R&D investment, number of patents or academic production, and economic growth (figures not shown).

ConclusionsSince the early 2000s, UNESCO (Bindé, 2005) has emphasised the role of knowledge in fostering sustainable development, and in advocating inclusivity, digital literacy, and equitable access to information. Recent models, such as the quadruple and quintuple helix frameworks (Carayannis & Campbell, 2012), highlight the importance of integrating civil society and environmental sustainability into innovation ecosystems. This paper seeks to explore several key questions regarding the definition, measurement, and limitations of the Knowledge Society.

The first contribution lies in the clarification of what is meant by knowledge from an economic perspective. Drawing on both classical economic theory and more recent developments, we argue that knowledge is not merely an abstract or philosophical construct, but a tangible asset with productive capacity. This economic framing enables a more precise understanding of the augmentation of the knowledge-creating sector, with its strong effects within innovation systems, labour markets, and value-creation processes. Moreover, the study distinguishes between the symbolic and utilitarian dimensions of knowledge and emphasises its role in shaping technological progress and institutional competitiveness. In doing so, the paper provides a comprehensive and analytically grounded answer to the first research question.

The second main question, concerning the definition and essential characteristics of the Knowledge Society, is addressed through a broad economic lens. Rather than viewing it solely as an outcome of digitalisation or economic modernisation, the Knowledge Society is presented as a socio-technical configuration in which more and more resources are diverted from direct production to knowledge creation. This paper synthesises various theoretical approaches to underline its complexity, and comments on the elements closely linked to the Knowledge Society, such as lifelong learning, interdisciplinary collaboration, civic engagement, and institutional adaptability. This enriched framework enables a more nuanced understanding of the drivers and barriers to knowledge-based development. Furthermore, it reflects the evolution of the concept over time, from early policy discourse to contemporary interpretations that recognise the roles of environmental sustainability and societal inclusivity. As such, the second research question is thoroughly explored and clarified.

The third research question, which is focused on how to advance towards a Knowledge Society and how to measure such progress, is approached through a resource analysis of the quaternary or knowledge-creating sector. The analysis of common proxies, such as GERD and R&D human resources, reveals the clear trend of steadily increasing resources dedicated to knowledge creation, while highlighting the risk of over-reliance on single quantitative indicators that may obscure qualitative dimensions. This analysis presents empirical examples to show how high investment levels do not necessarily correlate with knowledge outputs such as patents and academic research. While both indicators offer valuable insights into a country’s innovation capacity, neither is sufficient in its own right to capture the full complexity of knowledge production. Taken together, the analysis underscores the need for a more comprehensive and context-sensitive approach to measuring progress towards the Knowledge Society.

The paper acknowledges the complexity of a theoretical framework capable of explaining exceptions to the general trend. Countries can be affected by multiple factors, including culture, economic policy, demographics, and the characteristics of dominant industries. Even country-level measurement is somewhat arbitrary, since although many factors, such as legal and political structures, may be similar within a country (and differences exist between regions or states with different legal status), regional disparities in development and income can be significant. Thus, despite considerable progress, the question remains open, particularly regarding the development and validation of integrated and adaptable measurement tools. A multidimensional framework that incorporates institutional quality, education systems, openness, collaboration networks, and digital infrastructures is therefore essential in order to move beyond narrow proxies and to achieve a more holistic understanding of how knowledge underpins social and economic transformation. The governance of knowledge is not straightforward: it involves navigating the complexities of policy coordination across multiple domains, including education, research, and economic development (Chou et al., 2017). This interconnectedness underscores the need for a holistic approach to knowledge management that considers the diverse factors influencing knowledge production and absorption. The emergence of transdisciplinary approaches to research and knowledge production, as highlighted by Hernández-Aguilar et al. (2020), emphasises the need for contextualised solutions to complex problems (Chui, 2023).

The fourth question addresses the limits of the Knowledge Society, a topic explored through critical reflection and future-oriented inquiry. This paper highlights structural inequalities between countries. One relevant issue concerns the limitation posed by human resources dedicated to knowledge creation (Fig. 2, with the example of China). Governments can implement policies to increase R&D investment, but highly qualified personnel require a long period of training and, above all, must have vocation and a low time preference, that is, the will to sacrifice early career years with little or no income for the prospect of an uncertain higher income in the future.

Furthermore, if there is high demand from the productive system for highly qualified personnel (a trend exacerbated by the accumulation of knowledge and the speed of its creation, essential characteristics of the Knowledge Society), the economic incentive to engage in R&D activities will diminish. Moreover, not everyone has the capacity to engage in research creatively or, at least, productively. This clearly limits the human resources available to the Knowledge Society and constrains its growth. Another limiting factor is a society's capacity to invest in R&D, which, although linked to a country's wealth, is also influenced by cultural factors (e.g., time preference) and, above all, political considerations.

However, the very capacity of human beings to generate knowledge can constantly push the limits of the Knowledge Society, understood as the proportion of resources dedicated to knowledge generation, thereby creating a permanent vicious circle. For instance, the emergence of new technologies such as robotics and generative AI, exemplifies how R&D may both enable and disrupt societies, which forces a reconsideration of intellectual capital and human agency. Many activities performed by highly skilled personnel are repetitive and do not require creativity. Since AI can help these skilled human resources become much more productive, thereby freeing up invaluable personnel capable of and willing to acquire specialised knowledge, they can then be leveraged to create new knowledge. The constant development of technologies that multiply the productivity of workers is a constant feature of human history; the only difference today is the speed of development that makes the adjustment of the human resources to the new necessities of the productive structure a greater challenge.. New technologies have always been perceived as a threat by those workers that would have to move forward to new jobs (AlQershi et al., 2023). While the scope of this paper does not include the provision of definitive answers to all these concerns, it does succeed in framing them as essential components of the debate. This research question, therefore, remains partially answered, and invites continued interdisciplinary engagement to better understand the ethical, social, and ecological implications of knowledge-driven development.

Overall, this study provides solid and well-supported answers to the more conceptual and definitional questions raised herein, it advances crucial arguments regarding measurement and progress, and it opens valuable lines of critical inquiry regarding the boundaries and consequences of the Knowledge Society. These findings contribute not only to academic understanding but also to ongoing policy discussions regarding how to foster knowledge ecosystems of a more inclusive, adaptive, and sustainable nature.

Future research could explore the development of highly comprehensive and nuanced indicators to assess the evolution of Knowledge Societies. These might include, for instance, the proportion of the population actively engaged in knowledge creation beyond formal R&D roles, the sectoral dynamics that shape research activity, and metrics of a more granular nature: not only investments and outcomes per region, but also individual patent uses and royalties and their impact on productivity. The proposal regarding indicators that help measure the integration of the innovation system with the productive system is a major issue (Hu & Zhang, 2023). Moreover, special attention should be paid to the design and analysis of institutional frameworks that facilitate effective knowledge creation, interdisciplinary collaboration, and the co-creation of socially relevant innovation. Advancing in these directions would contribute towards building a more holistic, inclusive, and policy-relevant understanding of how knowledge functions as a driver of societal transformation.

Understanding the limitations of quantitative indicators inevitably leads to a broader reflection on the institutional, educational, and societal dimensions that shape knowledge ecosystems. Rather than being confined to measurable outputs, the Knowledge Society should also be examined through the lenses of governance structures, learning environments, and civic participation.

CRediT authorship contribution statementRoberto Cervelló-Royo: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Carlos Devece: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. José Luis Galdón: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Juan J. Lull: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.