We map the intellectual structure of teamwork in project management (PM) using a triangulated bibliometric design to interrogate 16,320 Scopus records (1966–November 2023). Three complementary lenses—keyword co-occurrence (topical cohesion), bibliographic coupling (research front), and co-citation (conceptual foundations)—are interpreted through an IMOI team-effectiveness lens that organizes mediators (affective, behavioral, cognitive) by phase (forming, functioning, finishing). We also overlay AI-related terms and treat AI as a socio-technical mediator—a cognitive augmenter, a coordination infrastructure, and a learning/retention aid—rather than as a standalone topic. To enhance rigor, we document analytic choices in an Assumption & Parameter Log, apply anchor-based labeling rules (Interpretive Propositions), and assess robustness to threshold and resolution choices.

The results reveal three consolidated domains—project success, agile methodologies, and knowledge management—and two emergent domains—virtual/distributed teams and leadership—concentrated in construction and software contexts, where ERP and product development are increasingly prevalent. Across the maps produced, three mediators recur: coordination under uncertainty (behavioral), shared mental models/transactive memory (cognitive), and trust/psychological safety (affective). AI is most visible at topical and research-front layers (decision support, BIM analytics, context-aware allocation) and less embedded in the field’s foundational canon. We contribute a mediator-first account of PM teamwork that clarifies where AI lands in team processes, offer phase-specific guidance for matching AI affordances to mediators, and demonstrate a reproducible mapping protocol for exploratory bibliometrics. Limitations (single database, concept-measure gaps for AI) suggest the desirability of phase-aware, mechanism-level studies and cross-sector comparisons.

Teams are the primary vehicle through which contemporary organizations deliver complex projects. In project management (PM), effective teamwork determines whether dispersed expertise can be coordinated under uncertainty, deadlines, and interdependencies. Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI)—from BIM-enabled analytics (Hartmann & Levitt, 2010) and risk forecasting to context-aware task allocation and generative assistants (Tian et al. 2025)—are reshaping how teams share knowledge, coordinate work, and learn from experience (Strnad & Guid, 2010; Hsu et al., 2020). Yet adoption is irreducibly socio-technical: the same tools that enhance awareness, speed, and reuse can also erode interaction quality or trust if embedded without attention to team processes and leadership (Shaikh & Cruz, 2019).

Despite decades of scholarship on teamwork, project success, and digitalization, the intellectual landscape at the intersection of teamwork and PM remains fragmented across topics, sectors, and methods, and the role of AI is often treated as a list of tools rather than as part of an explanatory framework (Kanski & Pizon, 2023). What the field lacks is a synthesized, longitudinal map that distinguishes consolidated domains from emergent ones, links topical patterns to mediators—how affective, behavioral, and cognitive processes unfold across project phases—and shows where AI actually intervenes.

We combine three complementary lenses: keyword co-occurrence (what we talk about; topical cohesion), bibliographic coupling (who is working on what now; the research front), and document co-citation (why we think that way; conceptual foundations). We do not interpret clusters by labels alone: we read them through the IPO and IMOI frameworks tradition of team effectiveness (Inputs → Process/Mediators → Outcomes → Inputs), organizing mediators (affective, behavioral, cognitive) by phase (forming, functioning, finishing). Table 1 illustrates this matrix. It will serve, after it has been enriched with AI-affordances through the literature review (Table 2), as the basis on which to interpret clusters in the results. This analysis makes the IMOI feedback loop explicit, and we use it as the lens for interpreting the maps.

Teamwork framework. Adapted from (Ilgen et al., 2005).

Phase × Mediator matrix for teamwork in projects (adapted from IMOI; Ilgen et al., 2005), with illustrative AI-affordances and an Outputs→next-cycle Inputs row making episodic feedback explicit.

The central stance of the paper is to theorize AI as a mediator, not a standalone “topic”; we operationalize this through an AI overlay on each map.

Methodologically, we make the interpretative step explicit and reproducible. The selection of the database, document selection criteria, thresholds, counting/normalization, clustering choices, and Interpretive Propositions (IP1–IP5) govern how clusters are labeled (anchor-based), checked for coherence/distinctiveness, triangulated across lenses, and mapped to mediators. We also record the robustness of threshold and resolution choices, showing that core structures are stable while differences concentrate at the periphery.

We pose three research questions:

RQ1. Which clusters are relevant in the PM field when exploring teamwork?

RQ2. What notable findings cut across teamwork in PM?

RQ3. In what ways does AI reshape collaborative practices and decision-making in complex project systems?

This study advances theory by shifting from topical labels to mediators, showing how AI operates as a mediator within the IPO and IMOI framework. It integrates different bibliometric lenses to build a multi-level account of teamwork that connects foundations, mediators, and outcomes. Methodologically, it contributes a transparent triangulated mapping strategy that enhances interpretability and reproducibility. Overall, it clarifies how AI affordances shape coordination, trust, and leadership in project contexts.

The paper proceeds as follows. In Section 2, we present the literature review. Section 3 sets out the theoretical basis and the IMOI matrix used to interpret team mediators (Table 2). Then we present details of the methodological basis of the research and the robustness plan (Section 4). Section 5 presents the results across co-occurrence (Fig. 1–2), bibliographic coupling (Fig. 3), and co-citation (Fig. 4), applying the AI overlay and mediator mapping. These results are discussed from different perspectives in Section 6, considering implications for theory, practice, and method. Finally, in Section 7, we present conclusions, limitations, and avenues for future research.

Literature reviewTeams are social systems of interdependent individuals working toward shared goals, with performance shaped by cognitive, affective, and behavioral processes (Cohen & Bailey, 1997; Mathieu et al., 2017). Definitions of “teamwork” vary across psychology, sociology, and management; meta‑reviews note substantial heterogeneity and a proliferation of models, underlining the need for integrative lenses (Salas et al., 2007; Taveira, 2008). In the current work, AI‑enabled systems are treated as socio‑technical artifacts that can augment—or in some cases reshape—these processes. Automating routine tasks, providing feedback, and mediating communication may strengthen cohesion and coordination, yet excessive automation can also reduce interaction quality and erode trust if poorly integrated (Almutairi et al., 2025; Shaikh & Cruz, 2019).

From inputs to processes and mediators: team‑effectiveness frameworksClassic IPO models (McGrath, 1964; Hackman & Morris, 1975) evolved into IMOI frameworks that emphasize mediators (affective, behavioral, cognitive) across forming, functioning, and finishing phases (Ilgen et al., 2005). The coordination infrastructures highlighted by empirical work are trust and psychological safety (forming), managing diversity and adaptation (functioning), and shared mental models/transactive memory (Edmondson, 1999; Jehn et al., 1999; Marks et al., 2001; Kozlowski & Ilgen, 2006).

AI applications naturally map onto these mediators and phases. (i) Forming: recommendation or fuzzy‑genetic systems can support team composition and role clarity (Strnad & Guid, 2010); (ii) functioning: group‑awareness and decision‑support tools (e.g., BIM analytics, ML‑based risk flags) scaffold coordination and adaptation; (iii) learning/finishing: generative systems and feedback agents can reinforce reflective learning and knowledge capture, contingent on psychological safety (Hartmann & Levitt, 2010; Hsu et al., 2020; Almutairi et al., 2025). These mappings position AI as a mediator that can enhance (or, if misused, hinder) team processes.

Project success and critical success factors (CSFs)Beyond the iron triangle, contemporary views of success incorporate benefits realization, stakeholder perceptions, timing, and sustainability (Atkinson, 1999; Ika & Pinto, 2022). People‑centric CSFs—communication, commitment, and leadership—remain prominent across industries, including construction, ERP, and agile (De Wit, 1988; Fortune & White, 2006; Chan & Chan, 2004; Fui‑Hoon Nah et al., 2001; Serrador & Turner, 2014; Dikert et al., 2016). Systematic reviews of AI in PM report contributions to planning, risk detection, monitoring, and knowledge reuse. They also caution, however, that empirical validation and theoretical grounding remain limited, calling for stronger constructs connecting AI mechanisms to success criteria (Bento et al., 2022; Taboada et al., 2023; Müller et al., 2024). In sectors such as construction, AI‑enabled risk analytics are becoming visible and practically relevant (Tian et al., 2025).

Teamwork within project management and AIPM structures teamwork at scale, yet capability gaps in teamwork remain salient (Chen et al., 2013; Lacerenza et al., 2018; Weiss & Hoegl, 2015). Professional competency frameworks (APM, 2015;AIPM, 2010a, 2010b;IPMA, 2015;PMI, 2007) explicitly include teamwork and the formation of cohesive teams as core competencies. In the context of Industry 4.0, PM is increasingly data‑driven; AI literacy and human‑AI collaboration are emerging as part of the PM competence set. Recent guidance from PMI frames AI as both an efficiency lever and a strategic capability (e.g., organizational AI transformation and AI for sustainability), reinforcing the socio‑technical nature of adoption (Kanski & Pizon, 2023; PMI, 2025a, 2025b).

When considering AI, some emerging themes have been highlighted by several authors at the teamwork-PM interface:

- •

Virtual and distributed teams. Foundational studies document trust, communication, temporal coordination, and cultural dispersion challenges (Jarvenpaa & Leidner, 1999; Lipnack & Stamps, 1997; Maznevski & Chudoba, 2000; Massey et al., 2003). AI can mitigate distance and temporal issues via context‑aware allocation, group‑awareness dashboards, and real‑time feedback, but can also introduce new dependency and trust concerns; the balance hinges on transparent use, error‑handling, and alignment with team routines (Lin, 2013; Lin et al., 2014; Gutwin et al., 2004; Almutairi et al., 2025).

- •

Agile teamwork. Agile emphasizes communication, responsiveness to change, and frequent delivery; teamwork quality correlates with success (Chow & Cao, 2008; Lindsjørn et al., 2016; Dingsøyr et al., 2018; Pikkarainen et al., 2008; Lee & Xia, 2010). Empirical work shows that AI can support backlog triage, task allocation, and requirements refinement, while adoption outcomes depend on innovation mindset and appropriation patterns, highlighting the human side of AI in agile teams (Lin, 2013; Lin et al., 2014; Felicetti et al., 2024).

- •

Knowledge management in projects. Research on knowledge creation, transfer, and retention (Nonaka, 1994; Davenport & Prusak, 2000; Grant, 1996; Szulanski, 1996; Lewis, 2004) frames how teams encode and access expertise. AI operationalizes aspects of transactive memory and boundary objects: knowledge‑based systems in BIM resolve design clashes and reduce cognitive misalignment; analytics can reveal tacit–explicit links and preserve project memory across handovers (Hsu et al., 2020; Hartmann & Levitt, 2010). In multi‑agent settings, cooperative AI underscores distributed decision‑making as a socio‑technical phenomenon (Zweigle et al., 2006).

The effects of AI depend on how tools are embedded within team phases and mediators (trust, safety, shared mental models) and on leadership that cultivates suitable appropriation (Edmondson, 1999; Müller & Turner, 2010; Zwikael & Meredith, 2021). This explains why similar tools yield divergent outcomes across projects and supports a contingency view of AI in teamwork.

Theoretical basisConceptual stance: multi‑perspective mapping of teamwork in PMWe view the teamwork–project management (PM) domain through two complementary lenses. First, team-effectiveness theory, often described through the Input–Process–Output (IPO) model and its extension to the Input–Mediator–Output–Input (IMOI) framework, organizes how inputs operate through mediators (affective, behavioral, cognitive) across the forming, functioning, and finishing phases to shape outcomes (Tables 1 and 2). This provides the mediator grid we use to interpret clusters in the results (Table 2).

Second, science‑mapping offers structural evidence at scale: co‑occurrence approximates topical cohesion, bibliographic coupling the research front, and co‑citation the conceptual foundations. Reading the maps through IMOI lets us translate network structure into phase‑specific mediators rather than labels alone.

Following Ilgen et al. (2005), we treat mediators as emergent states/processes with episodic feedback; outcomes in one episode become inputs to the next (IMOI). Accordingly, Table 2 includes an Outputs→Inputs row, and the right-hand column contains the AI-affordances to show where tools act on mediators.

We use Table 2 to locate where AI affordances are most likely to act (e.g., allocation dashboards on behavioral–functioning, BIM knowledge systems on cognitive–forming/functioning, and generative reviews on cognitive–finishing). This analysis addresses research question 2.

In the results, cluster labels and anchors are mapped to phase–mediator cells in Table 8 to identify whether AI acts primarily on affective (trust/safety), behavioral (coordination/adaptation), or cognitive (SMM/TMS) mediators.

Prior work highlights the following as the cognitive infrastructures that enable performance: trust/psychological safety in forming and managing diversity, adaptation, coordination in functioning, and shared mental models/transactive memory. We therefore expect clusters whose anchors and keywords align with (i) affective mediators (trust, safety), (ii) behavioral mediators (communication, coordination, conflict management, learning‑in‑action), and (iii) cognitive mediators (shared mental models, knowledge structures). Tables 2 and 8 (adapted from IMOI) summarize these elements and guide our interpretations.

Knowledge and coordination foundationsWe draw on the knowledge‑based view and adjacent theories to explain how teams encode and coordinate expertise: tacit vs. explicit knowledge and its conversion, working knowledge and reuse (Davenport & Prusak, 2000), transactive memory systems (TMS; who knows what?) as a cognitive scaffold (Lewis 2004), and boundary objects (Carlile, 2002) that allow heterogeneous actors to collaborate without full consensus. Information‑processing and media‑richness views further explain why different communication forms carry different loads under uncertainty (Daft & Lengel, 1986; Galbraith, 1973; Thompson, 1967). These perspectives help explain why some clusters knit diverse actors together (via shared representations) while others remain siloed.

AI can improve coordination and learning, but may also erode interaction quality and trust if introduced without attention to team processes and leadership. Empirical illustrations already present in the corpus include AI‑enabled BIM and knowledge systems in construction (Hsu et al., 2020), context‑aware task allocation in agile teams (Lin, 2013; Lin et al., 2014), decision‑support for team formation (Strnad & Guid, 2010), and appropriation of generative assistants by project managers (Felicetti et al., 2024), together with group‑awareness for distributed work (Gutwin et al., 2004). These cases anchor the AI‑as‑mediator stance we apply when reading clusters.

Assumptions (A) that connect networks to theoryTo keep interpretations disciplined, we make explicit the assumptions linking network patterns to constructs:

- •

A1 (Co‑citation ⇒ conceptual affinity): frequently co‑cited works indicate shared concepts.

- •

A2 (Bibliographic coupling ⇒ research‑front proximity): shared references signal similar current problems/methods.

- •

A3 (Co‑occurrence ⇒ topical cohesion): term co‑occurrence indicates a stable topic/construct.

- •

A4 (Co‑authorship/affiliation overlays ⇒ social structure): collaboration patterns can explain cognitive convergence.

- •

A5 (Temporal slicing): the 1966–2023 window captures the domain’s evolution.

- •

A6 (Granularity): topic‑level resolution targets meso‑topics (not macro disciplines or micro methods).

- •

A7 (Counting/normalization): fractional counting approximates participation while mitigating size bias.

- •

A8 (Ontology): clusters are interpretive constructs, not latent classes; we avoid causal claims.

This theoretical basis lets us map clusters to mediators: e.g., a “virtual teams” cluster that bundles trust, communication, and awareness terms will be read as affective and behavioral mediators in the functioning phase, with AI primarily acting as coordination infrastructure. A “knowledge management/BIM” cluster will be read as cognitive mediators (TMS/boundary objects) spanning forming, functioning, and finishing. We use this interpretive bridge consistently across co‑occurrence, coupling, and co‑citation maps.

Methodological basisResearch design and theoretical positioningThis study uses multi-technique science mapping to synthesize the intellectual structure at the intersection of teamwork (TW) and project management (PM).

We selected a combination of co-occurrence, bibliographic coupling, and co-citation analyses because each technique highlights a different dimension of the field. Co-occurrence reveals topical cohesion through keywords, bibliographic coupling captures the research front by linking documents with shared references, and co-citation identifies the conceptual foundations of the field by tracing how key works are cited together. Applying these methods in parallel enables triangulation between structural and conceptual perspectives, strengthening validity and allowing us to distinguish between consolidated and emerging domains. Moreover, the longitudinal design makes it possible to trace the evolution of teamwork and project management research over time, thus providing a comprehensive view of the field’s intellectual structure.

Our interpretive lens builds on the IMOI framework (Inputs-Process/mediators-Outcomes-Inputs): clusters are read through phase-specific mediators—affective, behavioral, and cognitive—during forming, functioning, and finishing phases (Table 2).

We treat AI affordances (e.g., allocation/awareness tools, BIM/knowledge systems, risk analytics, generative feedback) as potential mediators during the project phase, thereby linking the maps to theory rather than to labels alone.

Data source, scope, and retrievalWe followed recommended steps for bibliometric reviews (Rodrigo et al., 2024). The study covers 1966 to November 2023 and queries Scopus using: Title/Abstract/Keywords: "Project Manage*" AND ("Team*" OR "Team Work*" OR "Workgroup*"). The final sample comprises 16,320 documents (articles, books/chapters, and reviews).

Records exported from Scopus were inspected to reduce duplication and standardize fields (authors, sources, keywords). Network construction and normalization used VOSviewer (association strength; total link strength for reporting), which is suited to building and visualizing large bibliometric networks.

Network constructions and parametersKeyword co-occurrence (topical cohesion).

We analyzed 49,798 keywords from the Scopus sample and set a minimum co-occurrence threshold of 30 for inclusion in the map. The resulting structure yields 7 clusters (Fig. 1). For tabular listings (Annex 1), we additionally applied a high Total Link Strength filter (TLS> 100) to highlight the most connected terms.

Bibliographic coupling of documents (research front).

We constructed a coupling network for the 16,320 documents and identified eight clusters (Fig. 3). For interpretability in the narrative review, we highlight the 193 most-cited nodes (≥ 125 citations)—all of which are interconnected—while keeping analyses anchored in the whole network.

Document co-citation (conceptual foundations).

From 294,171 cited references, we applied a co-citation threshold of 20; 162 connected references formed five clusters (Fig. 4). This threshold balances coverage and coherence for identifying conceptual anchors.

Bibliographic coupling is more responsive to recent literature, while co-citation emphasizes foundational works; co-occurrence captures topical language. Reading these side-by-side supports convergent validation of themes.

AI overlay and IPO/IMOI mappingTo make the role of AI explicit, we created an AI affordances lexicon (e.g., BIM/knowledge-based systems, ML-based risk analytics, context-aware allocation/awareness, generative assistants). We overlay-tagged nodes and terms in each map and then mapped clusters to Table 2’s phase-mediator cells (affective/behavioral/cognitive × forming/functioning/finishing). This identifies whether AI in a given cluster primarily acts as a cognitive augmenter (shared mental models/TMS), a coordination infrastructure (awareness, allocation, risk signaling), or a learning/retention aid (after-action reviews, knowledge reuse).

Finally, we tagged AI terms and mapped them into Table 2’s phase–mediator cells, using the AI-affordances column as exemplars (e.g., BIM/KB as cognitive mediator, awareness/allocation as behavioral mediator, and generative AAR as cognitive mediator in the finishing phase).

Single-database decision and replicabilityTo ensure rigor and reproducibility, our methodological pipeline comprised four stages. First, we defined the scope and retrieved data from Scopus using carefully constructed search strings targeting teamwork and project management. Second, we cleaned and normalized the dataset, consolidating author names, keywords, and references to reduce duplication. Third, we applied multiple bibliometric techniques—co-occurrence, bibliographic coupling, and co-citation—using fractional counting with explicit thresholds for inclusion. Finally, we validated the robustness of the results by comparing across techniques and conducting longitudinal analyses. This stepwise approach is consistent with the comprehensive framework described by Rodrigo et al. (2024), but here it is tailored to the intersection of teamwork and project management.

As mentioned, analyses were performed on Scopus. Using one curated source maximizes replicability and metadata consistency across techniques. Integrating multiple databases would require a bespoke deduplication/disambiguation pipeline (DOI, author variants, reference parsing) not supported natively by the tools used, potentially introducing new degrees of freedom. We state this explicitly and mitigate coverage concerns through triangulation across techniques and longitudinal mapping.

The next section reports: (i) the co-occurrence map (seven topical clusters; Fig. 1 and longitudinal view in Fig. 2), (ii) bibliographic coupling (eight clusters; Fig. 3), and (iii) co-citation (five clusters; Fig. 4). Where relevant, we show how AI tags distribute across clusters and interpret them in Table 5 to identify whether AI primarily engages affective, behavioral, or cognitive mediators in each thematic area. Table 6 presents the analysis of clusters under the lens of Table 2.

ResultsThis section presents the results from the tasks outlined in the methodology, contrasting information from different units of analysis and indicators. We indicate below the most relevant documents and themes for the community, based on similarity indicators, along with a brief description of each research object, to identify the issues addressed by the mapped clusters.

The study covers 16,320 documents (1966–Nov 2023). We report three complementary maps: keyword co-occurrence (topical cohesion), bibliographic coupling (research front), and document co-citation (conceptual foundations).

Rather than re-stating topics, we interpret each cluster as indicating mediators (through what states/processes), and we report where AI appears to act on those mediators. For example, in the knowledge-management cluster, the proposed knowledge-externalization is observed through cognitive mediators (shared mental models/transactive memory), with AI affordances (BIM/KB systems) reinforcing those mediators.

Most cited documentsWe have included the results of an analysis of the most cited articles so that this ranking can be compared with the results that appear in the analyses indicated. Table 3 lists the top ten most-cited documents during the analysis period, highlighting their significance in management. The VOS algorithm maps 269 articles with over 125 citations, 203 of which are interconnected, and 82 have a high total link strength (TLS > 5). Notably, papers with the highest link values focus on product development projects (Edmondson, 2009; Lawson et al., 2009; Mishra & Shah, 2009), and knowledge management in construction (Oraee et al., 2017; 2019). When considering the most cited article authors, Browning (2001) introduces the widely used Design Structure Matrix (DSM). Researchers are keen to delve into project success factors (Belassi & Tukel, 1996) across various contexts, including IT (Wixom & Watson, 2001) and ERP implementation projects (Fui‐Hoon Nah et al., 2001).

Most cited documents.

| Authors | Title | Source title | Journal class | Cited by | Link Strength | Type document |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Browning, 2001) | Applying the design structure matrix to system decomposition and integration problems: A review and new directions | IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management | B | 1405 | 2 | Review |

| (Wixom and Watson, 2001) | An empirical investigation of the factors affecting data warehousing success | MIS Quarterly: Management Information Systems | A | 1074 | 1 | Article |

| (Geidl et al., 2007) | Energy hubs for the future | IEEE Power and Energy Magazine | - | 1056 | 0 | Review |

| (Fui‐Hoon Nah et al., 2001). | Critical factors for successful implementation of enterprise systems | Business Process Management Journal | C | 941 | 4 | Review |

| (Hertel et al., 2003) | Motivation of software developers in open source projects: An Internet-based survey of contributors to the Linux kernel | Research Policy | A | 865 | 4 | Article |

| (Heroux et al., 2005) | An overview of the Trilinos project | ACM Transactions on Mathematical Software | _ | 738 | 0 | Review |

| (Belassi and Tukel, 1996) | A new framework for determining critical success/failure factors in projects | International Journal of Project Management | B | 687 | 4 | Article |

| (Von Krogh et al., 2003) | Community, joining, and specialization in open source software innovation: A case study | Research Policy | A | 684 | 3 | Article |

| (Turner and Müller, 2003) | On the nature of the project as a temporary organization | International Journal of Project Management | B | 648 | 5 | Article |

| (Pich et al., 2002) | On uncertainty, ambiguity, and complexity in project management | Management Science | A | 607 | 11 | Article |

Table 3 also includes a column with a classification of the journals (Journal class) in which the articles were published. To determine a paper's impact, one method is to evaluate the quality of the journal where it was published. The papers are categorized based on a composite index derived from several journal rankings, including those from the French agency CNRS, the French National Foundation for Education FNEGE, ABS, and VHB. This index then classifies the journals using the conversion criteria detailed by Rodrigo et al. (2024)(see Table 1).

The “most-cited” list (Table 3) highlights canonical items; note, however, that link strength is a better indication of current centrality. Pich et al. (2002) show the highest link strength despite ranking 10th by citations, underscoring the difference between popularity and structural relevance.

Keyword co-occurrence (topical structure)We processed 49,798 keywords and set a minimum occurrence of 30, yielding seven clusters (Fig. 1). For readability in Annex 1, we highlighted terms with high total link strength (TLS > 100). We interpret each cluster via phase-specific mediators (Table 2) and indicate AI touchpoints observed in the corpus.

Below, we present the results of the clustering, accompanied by the interpretation of the resulting map (Fig. 1) and the proposed labels. Finally, we highlight some of the most noteworthy research, according to the indicators indicated in the methodology. Several categories emerge with regard to the content of each of the seven clusters identified.

- •

CO1 – Risk, Planning, & Construction/Industrial Management (Red, 123 items).

This cluster concentrates on project control work—planning, risk assessment, scheduling, contract management, and life‑cycle governance—with a strong construction emphasis. Through the IMOI lens, the dominant mediators are behavioral mediators in the functioning phase (coordination, scheduling, partnering, risk response) supported by cognitive artifacts (work breakdowns, risk registers) that help teams cope with uncertainty. Canonical risk definitions (likelihood × severity) and debates around objective vs. perceived risk (Zhang, 2011; Taroun, 2015) frame how teams interpret hazards during planning and delivery. The sectoral tilt to construction is consistent with this corpus and receives more attention than others, like oil, energy, and gas.

In this cluster, AI appears mainly as coordination/decision support: BIM knowledge-based systems that reduce clashes and bridge designer–constructor cognition (Hsu et al., 2020), and risk-analytics that flag schedule/cost exposure in real time (Tian et al., 2025). These tools bolster behavioral (coordination) and cognitive (shared models) mediators.

The findings suggest that the dominant mediators at play are behavioral, particularly during the functioning phase of projects. These include coordination among team members, scheduling activities, and handling risks. Cognitive elements emerge mainly when risks are codified and formally integrated into decision-making processes.

The role of AI is increasingly associated with Building Information Modeling (BIM) analytics and risk prediction tools, which support teams in anticipating challenges and adapting more effectively to uncertainties.

This pattern is especially evident in the construction industry, where reliance on BIM and risk-oriented practices makes the connection between behavioral and cognitive mediators, and their reinforcement through AI, particularly salient.

- •

CO2 – Technology & Decision-Making (Green, 95 items).

This cluster focuses on computer science, software development, and information technology, with a growing interest in teamwork performance. Data analysis, AI, robotics, and digital innovation are gaining attention. Making decisions is crucial to the management of projects (Stingl & Geraldi, 2017).

(Hsu et al., 2020) introduce a machine learning-based knowledge system that resolves design clashes in BIM (Building Information Modeling). This approach reflects how AI can integrate diverse expertise and bridge knowledge gaps between designers and constructors, reducing time and cognitive differences during construction.

(Strnad & Guid, 2010) showcase fuzzy-genetic models for team formation in project management, demonstrating how AI integrates subjective human factors like skillsets and dynamics with objective constraints like cost and deadlines. This fusion highlights the knowledge-driven adaptability of AI systems.

Timo and Levitt Raymond (2010) analyze how project teams adopt and adapt AI tools, emphasizing the interplay between technical possibilities and user perceptions. This sense-making approach highlights the grassroots innovation fostered by AI in local settings.

The use of heuristic techniques (e.g., genetic algorithms, simulated annealing) in AI-driven optimization, as explored by Hsu et al. (2020), indicates how AI solutions evolve dynamically with continuous feedback from real-world systems.

In this cluster, both behavioral and cognitive mediators play a central role, particularly in decision support and the development of team awareness. These mediators enable teams to interpret information, coordinate effectively, and adapt their strategies as projects evolve.

AI is explicitly embedded in this space, with strong connections to robotics and broader digital innovations. Illustrative examples include knowledge-based BIM clash resolution and heuristic or machine learning-driven optimization. Importantly, the adoption and integration of these tools are shaped by processes of team sense-making, as members collectively interpret and leverage technological outputs.

This cluster represents the densest AI-related cluster in the topical map, highlighting its centrality to current debates on digital transformation and the future of teamwork in project contexts.

- •

CO3 – HR Management & Performance (Blue, 78 items).

This cluster emphasizes communication, stakeholder, and program management, with organizational theories, strategy, and change highlighted by Artto et al. (2009). Management studies are most prevalent in the USA, UK, and China. The impact of leadership on team performance has been heavily researched, as has the role of organizational behavior in team development. Quality is a key concern, especially in healthcare. Additionally, project assessment and the role of teamwork in project implementation are explored, with studies on the Input-Mediator-Output (IMO) model being notable (Marks et al., 2001). The healthcare sector occupies a prominent position within this cluster.

This cluster emphasizes the role of affective mediators, such as trust and psychological safety, alongside behavioral mediators like leadership and coordination. These factors are crucial for fostering open communication, reducing interpersonal barriers, and ensuring smooth collaboration across teams.

Healthcare emerges as a particularly salient context in this area, where the interplay of trust, safety, and coordinated leadership is essential to achieving high-quality outcomes under conditions of uncertainty and pressure.

- •

CO4 – Knowledge Management (Yellow, 69 items).

This cluster closely links with Cluster 2, emphasizing software design, development, and knowledge management. Tools like case studies, literature reviews, and empirical research are central. Project managers, teams, and their impact on success, as studied by (De Wit, 1988), are key themes. The focus also includes distributed teams, virtual teams (Lee-Kelley & Sankey, 2008), team dynamics, and critical success factors in project performance.

In this cluster, cognitive mediators take a primary role, including shared mental models, transactive memory systems, and knowledge capture processes. These mediators are particularly relevant for distributed or virtual teams, where coordination and mutual understanding rely heavily on cognitive alignment rather than co-located interaction.

Regarding AI, knowledge-based systems and repositories naturally align with this setting, supporting the storage, retrieval, and dissemination of critical information across geographically dispersed team members, thereby enhancing collective cognition and decision-making.

- •

CO5 – Education (Purple, 51 items).

This is the area most isolated from the rest of the clusters and furthest from the center of the map. Curriculum development is particularly significant within the engineering field. Teaching strategies often incorporate project-based learning to investigate teams' behavior and their influence on project outcomes. Among learning methods, problem-solving emerges as the node with the highest link. It is a set predominantly focused on the fields of electrical and mechanical engineering.

Means et al. (2013) discuss the integration of AI in educational technologies. The Edison Project exemplifies how intuitive and iterative learning processes supported by AI can bridge gaps in non-technical teams. It emphasizes knowledge-sharing for project success, beyond rigid formal methodologies.

This cluster highlights the interplay of cognitive and behavioral mediators, particularly in learning and problem-solving processes. These mediators enable teams and individuals to acquire new knowledge, adapt strategies, and collaboratively address challenges effectively.

The integration of educational technologies is especially relevant here, with AI-supported learning tools providing personalized guidance, feedback, and scaffolding that enhance both individual and collective learning outcomes.

- •

CO6 – Person, Society, Institutions & Culture (Light blue, 25 items).

This cluster brings together people‑ and organization‑level levers that shape teamwork in project settings, most visibly personnel/HR concerns, product‑development practices, quality, and process improvement. Viewed through the IPO/IMOI lens, the emphasis lies on affective and behavioral mediators during the functioning phase (trust, communication, coordination, adaptation) and on cognitive supports that stabilize collaboration (shared mental models, transactive memory) when teams tackle complex, cross‑functional work.

Cluster 6 connects to the product‑development stream highlighted in the coupling map (e.g., knowledge sharing and collaboration effects on performance), where team cognition and interorganizational socialization are central mediators (e.g., Edmondson, 2009; Lawson et al., 2009; Mishra & Shah, 2009; Marsh & Stock, 2006). It also aligns with coordination under expertise differentiation: a recurring theme in software/product teams (e.g., Faraj & Sproull, 2000; Cataldo et al., 2006) that appears in the cross‑tables for product development (Table 7). Conceptually, Cluster 6 sits near the knowledge‑management tradition (tacit/explicit conversion, TMS, boundary objects) that forms a co‑citation backbone in the field, explaining why “quality/process” terms frequently occur together with “learning/retention” in project contexts.

This cluster involves a mix of mediators, with affective and behavioral factors being particularly prominent during the functioning phase. Key elements include the establishment of team norms, maintaining quality standards, and fostering continuous improvement. These mediators are closely linked to product development processes, where collaboration and adherence to standards are critical for successful outcomes.

- •

CO7 – Aerospace Engineering (orange 14 items).

This cluster is a small, method‑dense engineering island focused on systems engineering and spacecraft topics. We read it as a domain‑anchored, method‑centric cluster in which teamwork operates under high complexity and uncertainty. Through the IMOI lens, the emphasis is on behavioral mediators during functioning (coordination across tightly coupled subsystems and suppliers) supported by cognitive artifacts (architectures, interface contracts, system models) that enable decomposition and reintegration. This interpretation corresponds with the “most‑cited”/coupling anchors that are canonical for decomposition/integration and learning under uncertainty (e.g., Browning’s DSM (Browning, 2001); Pich et al. (2002) on ambiguity/complexity; Sommer & Loch (2004) on selectionism, and with views of projects as temporary organizations that must assemble specialized knowledge quickly (Turner & Müller, 2003). In other words, although the topical labels are aerospace‑specific, the teamwork mediators it foregrounds (coordination across interdependent components, iterative learning) are generalizable to other high‑reliability engineering contexts.

This cluster is more method- and engineering-oriented, with a narrower focus on teamwork per se but strong relevance in systems engineering contexts. Behavioral mediators, particularly during the functioning phase, play a key role in coordinating tasks, ensuring process adherence, and facilitating collaboration within technical teams.

The strong link between Clusters 6 and 7 reflects how people/process capabilities (Cluster 6) are co‑required with systems‑engineering representations (Cluster 7) when teams tackle complex product architectures: socio‑cognitive work (trust, coordination, learning) must be scaffolded by artifacts (DSM, interface models) to keep interdependencies tractable. These co-requirements appear as a bridge between team‑level mediators (affective/behavioral/cognitive) and engineering constraints, explaining the observed proximity despite the small size of Cluster 7.

Different types of mediators—behavioral, cognitive, and affective—shape team processes and outcomes, with AI supporting coordination, learning, risk management, and knowledge sharing. Behavioral mediators dominate during functioning, cognitive ones support distributed teams and problem-solving, and affective mediators foster trust and safety in high-stakes contexts like healthcare. AI applications range from BIM analytics and knowledge-based systems to robotics and AI-supported learning, with their adoption shaped by team sense-making and context-specific demands.

Longitudinal view. The evolution map (Fig. 2) shows Clusters 3 and 4 (HR/leadership and Knowledge Management) moving into newer territory, whereas Clusters 1, 2, 5, and 7 carry more established terms. This supports the emergence of leadership and knowledge-retention concerns within teamwork/PM.

Bibliographic coupling (research front)We built the coupling network on 16,320 documents and summarized eight clusters (Fig. 3). For narrative clarity, we refer to the 193 most-cited (those with 125+ citations (all interconnected)), while our analysis remains anchored in the full network.

The identified clusters correspond to the following themes:

BB 1 – Agile in Software Development; Complexity & Uncertainty (red, 37 items).

On the one hand, the most relevant documents found in this set are linked with agile project management methodologies applied in software development projects, such as the articles by (Lee & Xia, 2010; Maruping et al., 2009). On the other hand, papers like the ones developed by Pich et al. (2002) or Sommer and Loch (2004) explore the importance of complexity in project management performance. The complexity of projects can be measured according to the proposed taxonomy of Geraldi et al. (2011), in five dimensions: structural, uncertainty, dynamic, rhythm, and socio-political complexity.

This cluster highlights both behavioral and cognitive mediators. Behavioral mediators support coordination under changing conditions, while cognitive processes enable sense-making in situations of uncertainty, helping teams adapt and respond effectively.

AI is present indirectly, mainly through automation and analytics tools that facilitate agile workflows and support rapid decision-making.

BB 2 – Product Development Projects; Team Knowledge (green, 30 items) is focused on product development projects. The most relevant documents present their results about team knowledge management when developing this type of project (Edmondson, 2009; Lawson et al., 2009; Marsh & Stock, 2006). The set highlights also the importance of collaboration and its effect on team performance, as shown in the article by Mishra and Shah (2009).

This cluster emphasizes cognitive mediators, particularly knowledge sharing and transactive memory systems (TMS), which, together with behavioral collaboration, enhance team performance.

AI supports these processes by enabling the capture, storage, and reuse of knowledge across team and organizational boundaries, enhancing collective learning and efficiency.

BB 3 – Construction Projects; Partnering & BIM (blue, 29 items) focuses on construction projects, emphasizing the importance of partnering for success (Bayliss et al., 2004; Chan et al., 2004). BIM application in construction is highlighted in recent studies (Oraee et al., 2017, 2019), while Baiden et al. (2006) argue that fully integrated teams are not essential for effective delivery. Xue et al. (2020) map stakeholder-focused areas like sustainability and decision-making. Construction is notably distinct from other topics in the map.

This cluster involves both behavioral and cognitive mediators. Behavioral mediators focus on partnering and coordination, while cognitive mediators center on the development and use of shared mental models to align team understanding and actions.

AI is primarily reflected through BIM-centric knowledge and coordination tools, which support information sharing, task alignment, and collaborative decision-making.

BB 4 – Multicultural/Virtual/Distributed Teams (yellow, 23 items). Levina and Vaast (2008) found that country-context differences hinder collaboration, while organizational context differences are mediated through group practices. Vlaar et al. (2008) explore distributed teams' socio-cognitive acts and communication. Gutwin et al.´s (2004) emphasize the need for mutual awareness, and Sapsed and Salter (2004) discuss the limitations of project management tools in global teams. Kayworth & Leidner (2000) study virtual teams and coordination tools, while Karlsson & Ahlström (1996), identify factors affecting lean product development.

This cluster highlights affective mediators, which focus on building trust across boundaries, and behavioral mediators, which support communication and coordination to maintain effective collaboration.

AI is reflected in awareness dashboards and coordination tools, which can help mitigate the challenges of distance. However, their use also raises important questions regarding trust, ownership, and appropriation of information.

BB 5 – High-Performance Teams; Trust & Communication (purple, 21 items). The most relevant documents analyze the importance of trust in project teams (Diallo & Thuillier, 2005; Kadefors, 2004; McDaniel & McDaniel, 2004; J. K. Pinto et al., 2009), especially how to strengthen trust in virtual teams (Iacono & Weisband, 1997).

This cluster emphasizes affective and behavioral mediators, particularly trust and interpersonal processes, which are essential for sustaining effective team interactions.

AI carries the risk of over-automation, which can undermine these interactions if it is not carefully integrated and aligned with team dynamics.

BB 6 – ERP Implementation Projects (light blue, 20 items). This cluster has a wide dispersion of nodes, as can be seen in the map. The most cited document in this cluster is the investigation by Browning (2001), which considers the design structure matrix (DSM) a crucial tool for innovative solutions to decomposition and integration problems in this type of research. Critical factors for success in ERP implementation projects are another key topic (Ali & Miller, 2017; Amid et al., 2012; Fui‐Hoon Nah et al., 2001; Kumar et al., 2003; R. Malhotra & Temponi, 2010; Nah et al., 2003; Nah & Delgado, 2006; Ngai et al., 2008).

This cluster highlights both behavioral and cognitive mediators. Behavioral mediators support coordination across functions, while cognitive mediators involve the use and sharing of process knowledge to enhance team integration.

AI contributes through decision support systems and tools that enable knowledge capture and reuse, facilitating process integration and continuous improvement.

BB 7 – Leadership & Project Success (orange, 20 items). The key document (Scott-Young and Samson, 2008) links project management teams to success. Research includes critical success factors during project life cycles (Pinto and Slevin, 1988) and stakeholder perceptions of success (Davis, 2014). Aga et al. (2016) and Yang et al. (2011) examine how leadership styles affect teamwork and success. They propose a five-dimensional model emphasizing organizational context, team design, leadership, processes, and outcomes. (Belassi & Tukel, 1996) present a framework classifying critical factors affecting project performance.

In an interesting contribution, Zweigle et al. (2006) present a cooperative robotics framework where AI facilitates distributed decision-making in multi-agent systems. This underscores AI's potential in creating decentralized, collaborative systems where human-like interaction and adaptive strategies play central roles.

This cluster emphasizes affective and behavioral mediators, particularly transformational leadership and intentional team design, which connect effective teamwork to overall success.

AI influences leadership by shifting its focus toward sense-making and coaching, supporting leaders rather than replacing them, and enhancing their capacity to guide teams effectively.

BB 8 – Mixed / Bridging Topics (pink, 13 items) cluster. Centrally located and connected to other clusters, such as knowledge management, this cluster covers diverse topics, including knowledge management Lewis (2004), product development projects (Hoegl et al., 2004; J. B. Schmidt et al., 2001), trust in virtual teams (Jarvenpaa et al. (2004) virtual teams trust, coordination (Massey et al. 2003), and communications (Daim et al. 2012; Lowry et al. 2006). The most influential paper is by Hoegl and Proserpio (2004), highlighting that team members' proximity significantly impacts teamwork quality. There are also connections with ERP implementation and leadership clusters.

This cluster functions as a “connective tissue,” with behavioral and affective mediators—coordination, trust, and communication—linking knowledge management, ERP systems, and leadership practices.

AI manifests through cooperative agents in distributed settings, supporting multi-agent decision-making and enhancing collaboration across organizational boundaries.

To summarize, across these clusters, team mediators (behavioral, cognitive, and affective) span reflecting coordination, sense-making, trust, leadership, and knowledge processes in diverse contexts. AI supports these mediators in multiple ways: through automation, analytics, decision support, knowledge capture and reuse, awareness dashboards, BIM-centric tools, and cooperative agents for distributed decision-making. While AI enhances coordination, learning, and integration, its adoption requires careful embedding to avoid over-automation, erosion of trust, and the undermining of interpersonal interactions. Overall, AI complements rather than replaces human mediators, shifting leadership and collaboration toward sense-making, coaching, and adaptive coordination in complex and distributed work environments.

Document co-citation (conceptual foundations)From 294,171 references, a co-citation threshold of 20 yielded 162 connected references in five clusters (Fig. 4).

The following are the conceptual anchors that structure how the field reasons.

CC-1 – Project Success & Construction (red). The reference with the highest link strength is PMI (2013). Project success has emerged as a topic of considerable focus for researchers within this cluster. Notable papers in this cluster include works related to project success, such as studies by Atkinson (1999), Belassi & Tukel (1996), Belout & Gauvreau (2004), De Wit (1988), Fortune & White (2006), Ika (2009), Jugdev & Müller (2005), Mir & Pinnington (2014), J. K. Pinto & Slevin (1988, Serrador & Rodney Turner (2014), Shenhar et al. (2001). Research focusing on the leadership competencies of the project managers is also present, through articles like those by Aga et al. (2016), Müller & Turner (2007b, 2010), Turner & Müller (2005). It is worth mentioning that research within the construction field is also a core subset within this cluster, whose main documents are those by Baiden et al. (2006), Bruzelius et al. (2003), Egan (1998), Flyvbjerg (2014), Koskela (2000) and Sambasivan and Soon (2007).

This cluster links teamwork to outcomes through clearly defined success criteria and critical success factors (CSFs). Behavioral and affective mediators, particularly leadership and communication, play a central role in ensuring that teams meet these targets.

The construction industry emerges as a core context, where structured coordination and effective leadership are essential for achieving project objectives.

CC-2 – Methods & Organization Theory (green) (measurement, modeling, org design). Psychometric theory stands out as the major reference in the field, as claimed by Nunnally (1978), with the highest number of citations and the highest link strength. Organization theory is another core theory within this set; it has a substantial impact as it encompasses noteworthy papers in the field (Daft & Lengel, 1986; Galbraith, 1973; Podsakoff & Organ, 1986; Thompson, 1967). Regarding teamwork, the cluster includes behavioral research by Baron & Kenny (1986), Cohen (1988), and Podsakoff et al. (2003). Finally, the topics of team effectiveness and team processes are represented by the investigations of Cohen and Bailey (1997) and Marks et al. (2001), respectively.

This cluster also features papers focusing on a range of research methodologies. Structural equation modeling is explored in works by Anderson & Gerbing (1988), Fornell & Larcker (1981), and other statistical tools, such as multiple regression, are addressed by Aiken & West (1991), while multivariate data analysis is discussed in research such as that by Hair (1998).

This cluster provides the measurement and information-processing backbone for analyzing team mediators. It emphasizes methodological tools such as structural equation modeling (SEM) and regression techniques, alongside frameworks like media richness and information-processing theories, which support rigorous evaluation of behavioral, cognitive, and affective mediators.

CC-3 – Software Development & Teamwork (blue). The main references in this cluster, which is associated with teamwork in software development projects, are Boehm (1981), Carmel (1999), Carmel & Agarwal (2001), Herbsleb & D. Moitra (2001), Humphrey (1989), and Schmidt et al. (2001). The research methodologies more commonly employed for this topic are case study, whose main reference is Yin (2003), and qualitative data analysis (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Knafl, 1991; Miles & Huberman, 1994; Patton, 2002; Strauss & Corbin, 1990).

This cluster highlights behavioral and cognitive mediators operating under conditions of high uncertainty. These mediators are foundational for agile teamwork, enabling teams to adapt rapidly, coordinate effectively, and make informed decisions in dynamic environments.

CC-4 – Knowledge Management & Learning. The main focus of this cluster is knowledge management, whose main references are the research developed by Davenport and Prusak (2000); Grant (1996); Nonaka (1994); Schön (1983), and Wenger (1998). There is also an emphasis on learning themes, with important contributions by Kolb (1984), Lave and Wenger (1991), March (1991), and Senge (1990). One noteworthy pole is research dedicated to preserving knowledge, a topic intricately linked with teamwork (Edmondson, 1999).

This cluster emphasizes cognitive mediators, including tacit and explicit knowledge, transactive memory systems (TMS), and learning processes. It serves as the conceptual foundation for clusters related to knowledge retention and transfer, highlighting how teams capture, store, and disseminate critical knowledge to support ongoing performance.

CC-5 – Agile Methodologies. This cluster primarily revolves around agile methodologies, with a focus on papers that have already demonstrated significant impact in the field, such as those by Boehm and Turner (2005), K. Beck (1999), Beck et al. (2001), Cockburn (2002), Highsmith (2002), Poppendieck and Poppendieck (2003), and Schwaber (2004). Notably, these papers have been published more recently than those in other clusters, yet they have swiftly gained substantial influence in the knowledge area. This mirrors the increasing focus on agile methodologies within the research field.

Articles like Lin (2013) highlight how AI-driven, context-aware systems assist in agile task allocation, balancing quality and timeliness in distributed team setups. These systems address variability in team capabilities and task complexities, demonstrating AI’s ability to optimize dynamic and collaborative workflows (Lin et al., 2014).

This cluster emphasizes behavioral mediators, particularly iterative coordination, complemented by cognitive elements, such as the development of shared understanding.

AI appears primarily in recent publications, for example, through context-aware task allocation, reflecting the fact that it has been integrated since the publication of the foundational agile teamwork literature.

To summarize, team mediators—behavioral, cognitive, and affective—link teamwork to outcomes through leadership, communication, coordination, and knowledge processes. Methodological tools like SEM and media richness theory support their analysis. Cognitive mediators enable knowledge retention and transfer, while behavioral and cognitive ones underpin agile teamwork under uncertainty. AI is emerging in recent applications, such as context-aware task allocation, complementing foundational team mediators and enhancing adaptive performance.

RobustnessWe probed threshold and resolution sensitivity around baselines (co-occurrence 10–60, co-citation 15–25, citation cutoffs 100–125, and topic-level resolution corridor). The core cluster structures and anchors remained stable; observed differences affected peripheral nodes and cluster sizes rather than labels or anchor sets.

Across structural (coupling/co-citation) and semantic (co-occurrence) lenses, the backbone of the field is project success, agile, and knowledge management, with virtual teams and leadership consolidating as emergent themes. AI is present but uneven: strongest at the topical/research-front level (technology/decision-making; BIM; agile practices) and less embedded in the deepest conceptual anchors, consistent with the suggestion that industry adoption is outpacing theory and measurement.

DiscussionThe three maps, taken together (and summarized in Table 4), reveal three consolidated dimensions (D)—Project success (D1), Agile methodologies (D2), and Knowledge management (D3)—and two emergent ones—Virtual teams (D4) and Leadership (D5). AI references are concentrated in Technology/Decision-making, Knowledge management/BIM, and Agile, while Leadership and Virtual teams show AI as socio-technical mediators rather than standalone topics (e.g., awareness tools support trust), while generative feedback facilitates learning. The Construction and Software industries anchor most of the activity, with ERP and Product development emerging as distinct project types.

Summary results: co-occurrence, bibliographic coupling, and co-citation analysis.

D1 Project success (consolidated). Given the high rate of project failure (Chan and Chan, 2004; Hoegl and Gemuenden, 2001; Nah et al., 2003; Pinto and Slevin, 1988), this topic has attracted significant attention for many years across all sectors and industries. Identifying critical success factors remains a top priority. Teamwork emerges as a critical success factor to be considered, highlighting its significant impact on project outcomes (Cluster 7BB and 1CC). Recent research reinforces this result (Ika & Pinto, 2022).

Co-citation anchors (success criteria, CSFs) connect tightly to leadership/communication processes observed in coupling/co-occurrence. AI’s role appears in: forecasting, monitoring, and knowledge reuse. Conceptual integration is, however, still maturing.

D2 Agile methodologies (consolidated). These methodologies play a significant role in project management research, emphasizing the importance of teamwork. It is interesting to note that, despite being relatively young (introduced in 2001), they have already become a priority in the field of project management (Dikert et al., 2016; Serrador and Turner, 2014) (Clusters 2CO, 1BB, 3CC, and 5CC). Recent research reinforces these results (Marnewick & Marnewick, 2022). This discipline appears strong across all maps; AI's role in these methodologies reinforces task allocation, triage, and coordination under change.

D3 Knowledge management (consolidated). Given that project teams do not always work together (usually, a team is dispersed once the project is closed), there is a significant challenge and concern around how to retain knowledge, especially tacit knowledge. For many years, companies have sought tools to preserve the necessary knowledge, and it has proven to be a persistent and difficult endeavour (Clusters 4CC, 2BB, and 4CO). Hartmann & Levitt, 2010 present examples of various categories of knowledge, ranging from tacit to explicit. They propose a technique to enhance knowledge management and assert that it is possible to improve project management by managing knowledge more effectively. Cognitive backbone is considered a means of integrating tacit and explicit knowledge and as the mediator of the TMS; AI’s role is detected through BIM/KB systems and repositories.

D4 Virtual teams (emergent). The increasing prevalence of distributed and virtual teams has created the need to understand how to manage these work structures more effectively. The existing tools and methodologies seem insufficient, leading to the proposal of new ones. How to strengthen trust in virtual teams (Piccoli & Ives, 2003) and commitment (Daniel et al., 2017) emerges as a topic of high interest for researchers (Cluster 4BB and 6CO). In this dimension, affective and behavioral mediators (trust, communication) appear with AI awareness/coordination tools as complementary mediators.

D5 Leadership (emergent). Competences such as trust, communication, collaboration, and coordination are crucial for project success (Cluster 5BB). The literature has often focused on centralized power in project management, typically vested in a single individual, the project manager (e.g., Aga et al. (2016), Müller & Turner (2007a), Zhang et al. (2018). Research by Scott-Young et al. (2019) emphasizes shared leadership in project teams, highlighting numerous research opportunities in various contexts. Recent studies further support these findings (Zwikael & Meredith, 2021). We have discovered the importance of affective/behavioral mediators as pathways to success; AI’s role shifts leadership tasks toward sense-making/coaching (not replacement).

Complementing these insights, Ali Soomro et al. (2024) highlight the role of shared leadership in promoting team innovation in construction projects. Their study shows that knowledge-sharing mediates this effect, with open-minded team norms strengthening the link. This underscores the importance of leadership and knowledge management for enhancing innovation and project performance in construction.

The dimensions presented in this analysis directly address our first research question (RQ1).

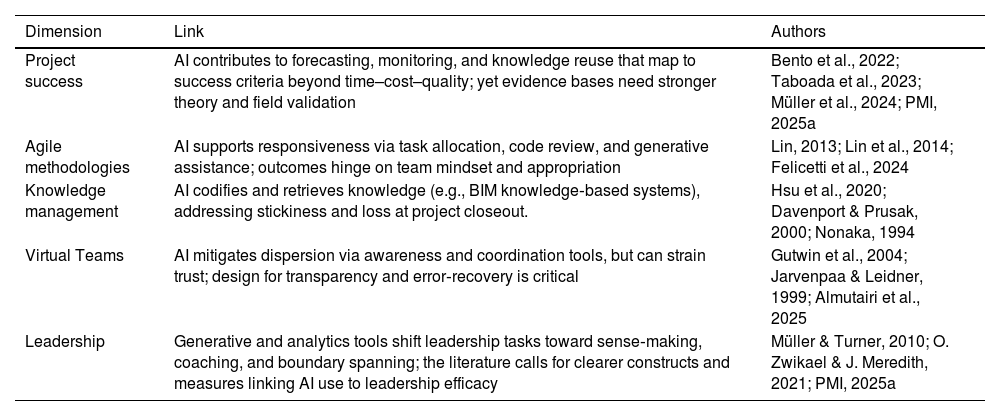

Table 5 presents a summary of links between AI and the five dimensions presented previously.

Summary of links between AI roles and the dimensions identified in this study.

| Dimension | Link | Authors |

|---|---|---|

| Project success | AI contributes to forecasting, monitoring, and knowledge reuse that map to success criteria beyond time–cost–quality; yet evidence bases need stronger theory and field validation | Bento et al., 2022; Taboada et al., 2023; Müller et al., 2024; PMI, 2025a |

| Agile methodologies | AI supports responsiveness via task allocation, code review, and generative assistance; outcomes hinge on team mindset and appropriation | Lin, 2013; Lin et al., 2014; Felicetti et al., 2024 |

| Knowledge management | AI codifies and retrieves knowledge (e.g., BIM knowledge‑based systems), addressing stickiness and loss at project closeout. | Hsu et al., 2020; Davenport & Prusak, 2000; Nonaka, 1994 |

| Virtual Teams | AI mitigates dispersion via awareness and coordination tools, but can strain trust; design for transparency and error‑recovery is critical | Gutwin et al., 2004; Jarvenpaa & Leidner, 1999; Almutairi et al., 2025 |

| Leadership | Generative and analytics tools shift leadership tasks toward sense‑making, coaching, and boundary spanning; the literature calls for clearer constructs and measures linking AI use to leadership efficacy | Müller & Turner, 2010; O. Zwikael & J. Meredith, 2021; PMI, 2025a |

The main industries where this research was conducted are software development (Clusters 2CO, 1BB, and 3CC) and construction (Clusters 1CO and 1CC), both of which have been extensively analyzed in efforts to improve project management practices. In construction, there is a notable focus on megaproject management (MPM) evolution, with Denicol et al. (2020) and Li et al. (2018) identifying key features through bibliometric analysis. They link MPM to five management theories: Institutional Theory, Organizational Effectiveness Theory, Stakeholder Theory, Top Management Team Theory, and Resource Dependence Theory. The authors conclude that it is premature to establish classic texts or a systematic theory for megaprojects, indicating that it remains an emerging field (Li et al., 2018).

These results align with recent findings by Slavinski et al. (2023), who highlight the significance of project management research in the construction industry. They express concerns about the high uncertainty associated with successfully managing construction projects, linking it to risk management.

The bibliographic coupling analysis indicates growing interest in two emerging project types: product development projects (Cluster 2BB) and ERP implementation projects (Cluster 6BB). While ERP research focuses on successful implementations, studies on product development also explore knowledge management, virtual teams, and leadership styles, emphasizing cooperation and collaboration (see Table 6). This is consistent with the results of Idrees et al. (2023), who show that, for product development projects, knowledge management is a key strategic asset that enhances efficiency, innovation, and performance. By systematically managing knowledge, high-tech firms can improve project outcomes and align new product development efforts with broader organizational goals, strengthening their competitive advantage.

Mediators’ matrix for teamwork (affective, behavioral, and cognitive) in projects, with results of co-ocurrence (CO), bibliometric (B), and co-citation (CC) analysis. Illustrative mediators of AI affordances have been included.

Overlaying AI-related terms and exemplars from the corpus reveals three typical mediator pathways (see Table 5). First, cognitive augmenters (e.g., BIM knowledge-based systems or lessons-learned retrieval tools) contribute to the development of shared mental models and transactive memory systems, spanning the process from the forming phase through functioning to finishing. Second, coordination infrastructure (e.g., context-aware allocation, awareness dashboards, and risk signals) supports adaptation and temporal coordination, particularly within the functioning phase. Finally, learning and retention aids (e.g., generative feedback for after-action reviews) foster reflection and knowledge capture during the finishing phase. This clarifies how AI appears inside clusters: as a mediator acting on affective/behavioral/cognitive mediators, contingent on appropriation and leadership (Table 6). This analysis addresses research question 3.

We will now analyse the sensitive aspects of the sector—construction and software—and the boom in the ERP and product development branches (see Tables 7 and 8).

Connections between established and emerging clusters with identified industries.

Relationship between dimensions.

Table 7 illustrates connections (through publications) between established and emerging clusters, identified industries, and the predominant use of agile methodologies in software development. In contrast, virtual teams appear less common in the construction industry. Several of the analysed documents do not target any particular industry.

Table 8 explains the relationships between various dimensions by referencing specific documents that dig into topics within each dimension. A couple of examples are the studies by Lipnack and Stamps (1997) and Maznevski and Chudoba (2000), which explore behaviours and dynamics in virtual teams. Other interesting interlinkages between dimensions can be found in the studies by Koskinen et al. (2003), which demonstrate, for instance, how language usage, mutual trust, and proximity influence the utilization of tacit knowledge in project work, highlighting the connection between knowledge management and interpersonal competencies.

Finally, the boxes in Tables 7 and 8 without associated references indicate a lack of relevant studies at the confluence of different disciplines or between disciplines and the industries indicated, suggesting the potential avenues for future research indicated in our conclusions.

ConclusionsIn this paper, we present the results of our research mapping the intellectual structure of teamwork in project management (PM) using a triangulated bibliometric design over 16,320 Scopus records (1966–November 2023). Three complementary lenses—keyword co-occurrence (topical cohesion), bibliographic coupling (research front), and co-citation (conceptual foundations)—are interpreted through an IMOI team-effectiveness lens that organizes mediators by phase (forming, functioning, finishing) and type (affective, behavioral, cognitive). We also overlay AI-related terms and treat AI as a socio-technical mediator—a cognitive augmenter, a coordination infrastructure, and a learning/retention aid—rather than as a standalone topic.

These maps collectively show the answer to our research questions. Across lenses, the backbone of the field comprises three consolidated domains—project success, agile methodologies, and knowledge management—and two emergent domains: virtual/distributed teams and leadership. Industry concentration is strongest in construction and software, with ERP and product development as project types where teamwork mediators are probed explicitly (Figures 1–4).

Three mediators recur regardless of sector (Table 2): (i) coordination under uncertainty (behavioral mediators in the functioning phase), (ii) shared mental models and transactive memory (cognitive mediators) that stabilize collaboration, and (iii) trust/psychological safety (affective mediators), especially for virtual and multicultural settings. The research-front (coupling) sharpens how these are achieved (partnering, iterative coordination, knowledge scaffolds), while the co-citation map clarifies why they matter (success criteria, information-processing, KM/learning theory) (Tables 5 and 6).

AI appears most visibly at the topical/research-front level (co-occurrence and coupling) and is less embedded in the deepest conceptual anchors (co-citation). By making the Outputs→Inputs feedback explicit in Table 2, we frame AI effects as episode-to-episode changes in mediators (e.g., learning captured at finishing becomes an input for forming).

The analysis shows that AI mediates teamwork by augmenting cognition, enabling coordination, and supporting learning, with its impact shaped by appropriation and leadership (Table 6).

Theoretical contributionsFirst, the analysis moves from labels to mediators: by reading clusters through the IPO→IMOI framework, it goes beyond topical labels to identify phase-specific mediators. In this view, themes such as virtual teams and leadership are not merely ‘topics’ but rather affective and behavioral pathways that explain how project success is achieved across contexts. Second, it conceptualizes AI as a mediator: treating AI as a set of affordances acting on mediators helps to clarify the mixed results reported in the literature, since tools that enhance awareness or knowledge access can strengthen coordination and shared cognition—or undermine trust—depending on team climate and leadership. Finally, it highlights convergence across lenses: the alignment between coupling (research front) and co-occurrence (topical), together with the links to KM/learning and success/measurement in co-citation, supports a multi-level account of teamwork that connects conceptual foundations, measurable mediators, and project outcomes.

Practical implicationsThis paper has practical implications for project management and competency development. Practitioners should map AI tools to specific mediators and project phases, selecting supports according to the mediators they target, such as onboarding/coaching (in the forming phase, trust and role clarity are key), awareness/re-prioritization (in the functioning phase, coordination and adaptation enable teams to align efforts), and generative after-action review or lessons-learned retrieval (in the finishing phase, learning and retention ensure that knowledge and lessons are captured for future use).

Transparency and recovery should be designed into AI systems, making recommendations and uncertainties visible while pairing automation with explicit error-handling routines to protect trust. Cognitive scaffolds should be strengthened by investing in shared representations (e.g., BIM, checklists, repositories) and maintaining them as boundary objects across contractors and suppliers. Leadership development should focus on AI literacy, training leaders in human-AI teaming, communication of analytics limits, and coaching teams in AI appropriation. Finally, sector-specific tailoring is advised: for construction, AI and BIM analytics should be coupled with partnering; for software and agile contexts, AI can support triage and coordination under change; and in ERP, retrieval and checklist tools can reduce rework at interfaces.

Methodological contributionThe study contributes methodologically through several avenues. Triangulated science mapping—combining co-occurrence, coupling, and co-citation—provides convergent validation of thematic structures and mitigates over-interpretation from any single lens. Explicit interpretive rules, such as the Assumption & Parameter Log and Interpretive Propositions (IP1–IP5), enhance transparency and reproducibility in cluster labeling, addressing a common critique in exploratory bibliometrics. The overlay of AI with the IMOI mapping strategy demonstrates where AI concepts reside within the structure of the field (topical/research-front versus conceptual core), enabling a mediator-level discussion rather than a mere list of tools.

The paper proposes several testable propositions for future research. First, regarding cognitive augmentation (P1) in knowledge-intensive projects: AI that externalizes and retrieves shared representations (e.g., BIM, knowledge-base repositories) is expected to enhance shared mental models and transactive memory systems, thereby mediating improvements in coordination quality.

Second, coordination infrastructure (P2) suggests that in high-uncertainty settings, AI’s contribution of real-time awareness and task re-allocation can reduce coordination losses, conditional on transparent use and established error-recovery norms.

Third, the trust boundary (P3) indicates that the positive effects of AI on performance are contingent on trust and psychological safety; without these conditions, monitoring and feedback tools may impair interaction quality and learning behaviors.

Finally, leadership shift (P4) highlights that AI repositions project leadership toward sense-making, coaching, and boundary spanning rather than direct substitution, with leadership style moderating AI’s impact on mediators.

Two limitations of this study are its use of a single database and the fact that AI is conceptually under-specified in co-citation analyses. Future research should validate these findings with multiple databases, develop measures linking AI functions to mediators and outcomes, test phase-specific and trust-boundary effects through field experiments or panel designs, explore cross-sector generalizability, and examine multi-team systems to understand how team-level mediators scale to organizational outcomes.

Taken together, the maps portray a field anchored in project success, agile, and knowledge management, with virtual teams and leadership consolidating as emergent domains. AI is present but uneven—most active at the research front and topical layers, less so in the foundational canon—consistent with a socio-technical view where tools alter mediators rather than replace human collaboration. Grounding future studies in mediator-first models and phase-aware designs will help convert today’s adoption patterns into cumulative theory and reliable practice.

Ultimately, teamwork remains the critical success factor in project management; AI will matter not as a substitute for collaboration but as a mediator that—when properly embedded—enhances trust, coordination, and shared knowledge in complex project environments.

CRediT authorship contribution statementIsabel Ortiz-Marcos: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Laura Rodrigo: Writing – review & editing, Software, Methodology, Investigation. Miguel Palacios: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Supervision. Rocio Rodriguez-Rivero: Writing – review & editing, Visualization.