The Request for Proposal (RFP) process, which is used extensively by industry and all levels of government for the procurement of products and services, is generated independently of later project execution. This paper examines the impact of RFP project requirements risk on project performance. Furthermore, utilizing Transactive Memory Systems (TMS) theory, we identify “proposal overlap” between the RFP team and the final project execution team as a key moderator of this relationship. The results support our hypotheses that proposal overlap mitigates the impact of requirements risk on project performance. We discuss implications for project management and develop future research avenues.

Projects improve the competitive position of an organization and contribute to company growth through increased earnings and cost reductions (e.g., Verner et al., 2014; Rodríguez-Rivero et al., 2020; Malherbe, 2022). Although over time companies have grown more heavily dependent on the successful delivery of projects for strategic and operational purposes (Project Management Institute, 2018; Crawford et al., 2022), project implementation is often accompanied by great risk (e.g., Smith et al., 2014); that is; any unforeseen event or condition that may jeopardize the project’s objectives, thereby impacting its successful completion (Boehm, 1991; Nidumolu, 1995; Project Management Institute, 2017; Wallace & Keil, 2004).

Previous research has primarily concentrated on the inherent risks associated with projects, with extensive studies at the organizational level that encompass both the challenges encountered during project execution and throughout the entire project lifecycle (Sundara et al., 2021; Ropponen & Lyytinen, 1997; Wallace & Keil, 2004; Zhang et al., 2018). The literature has shown that a multitude of risks negatively affect project performance and that managing these risks is positively correlated with successful performance (Barki et al., 2001; De Bakker et al., 2010).

However, with the constant change of organizational forms, especially the frequent occurrence of management processes on reengineering and outsourcing, organizations are constantly interacting with other organizations (Bodrozic & Adler, 2018; Gao, 2024), especially in the form of the Request for Proposal (RFP), which is ubiquitous in industrial and platform enterprises and at all levels of government (e.g., Gransberg & Barton, 2007). As the individuals involved in the RFP are not necessarily the same individuals who execute the proposal, uncertainty and information asymmetry can thus increase project risks. Although previous studies have highlighted the risks associated with projects, they have ignored the associated incongruencies between those proposing and those carrying out the project. Indeed, some RFP teams are formed for specific projects and then dissolved while others can carry over, at least partly, to final project completion (Payne, 1995). Accordingly, we focus on the overlap between the RFP team and the individuals who eventually execute the proposal.

Transactive Memory Systems (TMS) is defined as learning, storing, and remembering the expertise of each member of the project team; that is, knowing in detail “who knows what” and “who does what” (Antunes & Pinheiro, 2020; Ode & Ayavoo, 2020; Guo et al., 2022; Argote & Ren, 2012; Lewis, 2003; Lewis & Herndon, 2011; Wang et al., 2018; Wegner, 1985). Utilizing TMS, we argue that the higher overlap of memories, associated knowledge, and information between the RFP team and the team executing the project, hereafter referred to as “proposal overlap,” will mitigate project risk and facilitate final project execution. In situations of higher proposal overlap, team members will be more motivated to rectify their differences since the team is not temporary (Johnson & Johnson, 2005).

We argue that the degree of proposal overlap is of central importance for reducing risk and for successful project completion. Specifically, we investigate if the relationship between project risk, particularly requirements risk, defined as requirements arising from interactions with stakeholders (e.g., users), such as constantly changing underidentified, incorrect, or unclear requirements (Wallace & Keil, 2004), and performance is affected by the overlap of proposal development and project execution team members. Drawing on a sample of 503 project managers, we found support for our hypotheses that the negative impact of project risk on project performance can be mitigated by proposal overlap.

Our research responds to the call in the literature for more empirical evidence regarding the relationship between project risk and performance (Liu, 2016). There is currently a paucity of empirical data on this relationship (Bakker et al., 2010; Liu & Wang, 2014; Verner et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2018), which we fill with a large-scale empirical study. We enhance project management risk theory by highlighting and integrating the concept of interdependencies between RFP and project execution into the risk-performance equation utilizing the theory of TMS to address the lack of research focus on risks posed by the RFP. Indeed, we are the first empirical study to stress and highlight the importance of the RFP process and the associated risks. By providing a theoretical foundation with TMS and showing the importance of proposal overlap, we offer a practical, usable tool that is easy to implement and effective in practice (Bakker et al., 2010; Bannerman, 2008; Taylor et al., 2012). Practitioners are encouraged to design participation in the RFP process to ensure sufficient overlap between the RFP team and the final execution team to realize the performance benefits provided by TMS. Finally, we suggest detailed future research on the RFP and call for a process perspective.

Theoretical backgroundFrom request for proposal to project executionA project is a temporary endeavor undertaken to create a unique product, service, or result (Kerzner, 1987; Project Management Institute, 2017) that relies on a project manager and technical, financial, legal, and manufacturing specialists, as needed, for successful project completion (Prahalad & Ramaswamy, 2004).

Projects often begin with an RFP, which generally proposes undertaking a study to analyze a problem or to provide a service or product to meet a need of the buyer (Freed & Roberts, 1989). The RFP defines the budget, scope, planning or schedule, and management of the project (Elonen & Artto, 2003), it specifies execution methods, objectives, expectations, benefits, and team member qualifications (Freed & Roberts, 1989). However, the RFP procurement process has received scant attention in the literature (Mandell, 1986), with few papers dealing with this process.

The proposal development process requires attention to detail and a complete understanding of the buyer’s requirements (White & Bales, 2018). The primary purpose of the RFP is to transmit the buyer’s needs to possible sellers (Porter-Roth, 2002; Sutterfield et al., 2006). Once submitted, the customer evaluates the seller’s proposal and, based on this evaluation, will accept or reject the proposal. If accepted, project execution begins using the performance parameters as defined in the proposal (Sedano, 2016).

The RFP and submitted proposal build the foundation for clear and accurate communication between the contractor and the customer (Porter-Roth, 2002). The proposal as agreed to is then incorporated into the contract, obligating the supplier to comply with what is in the proposal. Thus, both parties operate using the same agreed-upon requirements, schedules, costs, and so on (Cobb & Divine, 2016). The agreed-upon project plan and schedule in the proposal becomes the primary method for organizing and controlling project execution, detailing how the project is to be implemented, what the first steps are, and how performance will be measured (Cobb & Divine, 2016; Porter-Roth, 2002). Fig. 1 summarizes the sequence of events that occur during the RFP procurement process.

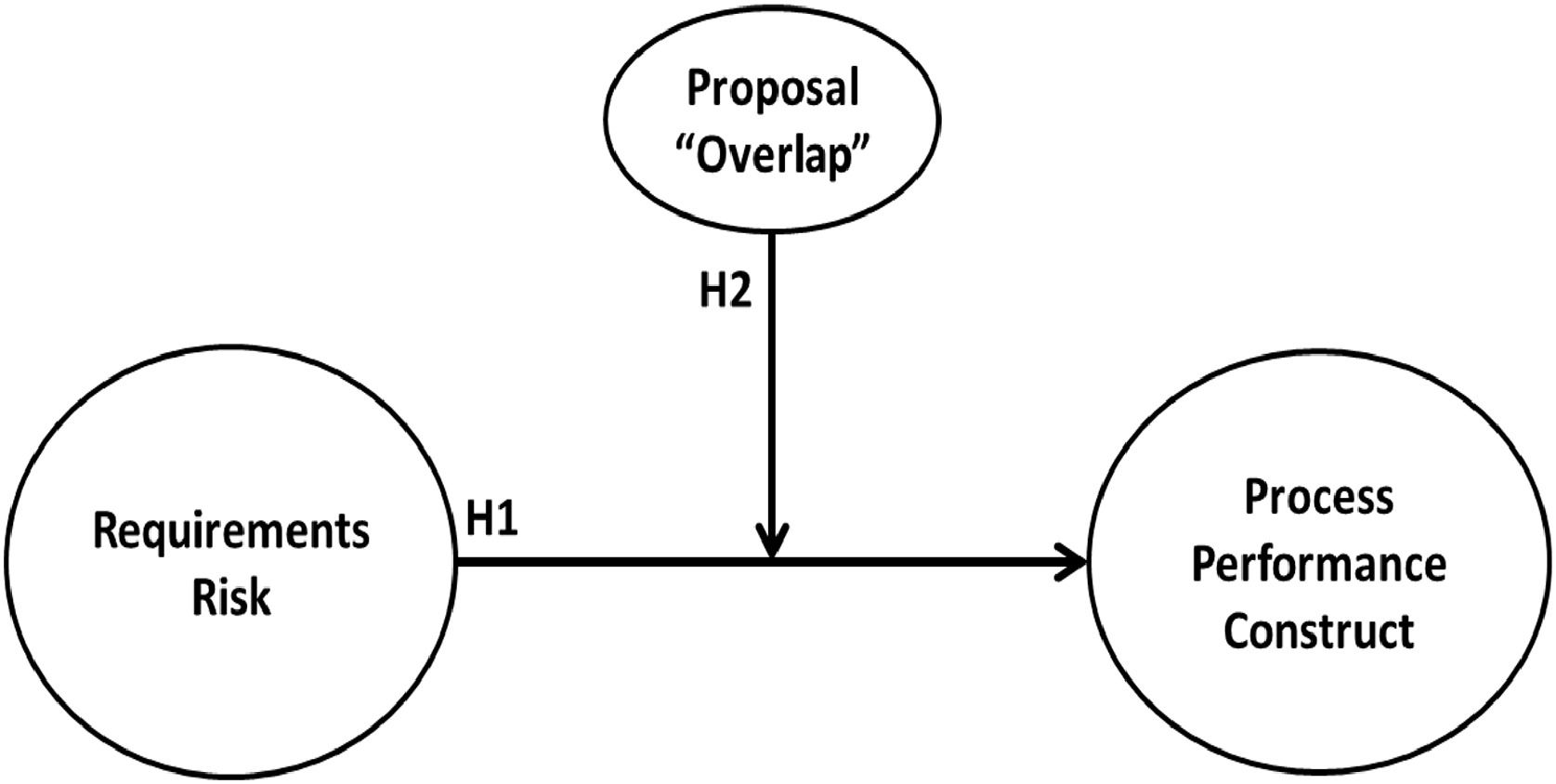

To generate a response to the RFP, a proposal development team is formed by the seller. Once the buyer approves the submitted proposal (with or without changes), the final project is executed by the seller’s project team. The project execution team may consist of members of the proposal development team or may have no overlap. As shown in Fig. 2, we propose that the main effect on project performance is moderated by project overlap.

HypothesesProject risk and performance“There are few topics in the field of project management that are so frequently discussed and yet so rarely agreed upon as the notion of project success” (Pinto & Slevin, 1988, p. 67), a clear definition of which remains elusive (De Bakker et al., 2010; Dvir et al., 2003). Historically, the literature has focused on specific measures of time, cost, and quality, the “iron triangle” (Atkinson, 1999), considered as traditional project success criteria (Aloini et al., 2007; Atkinson, 1999). Typically, the project manager’s goal is to bring a project to completion within budget, stay on schedule, and meet product performance goals (Dvir et al., 2003). For example, according to the Federal Acquisition Regulations (FAR), it is the responsibility of the issuing agency to ensure that the government gets what it paid for in terms of cost, schedule, and quality. Loss of control of any of these constraints poses a threat to the project’s success (Chen et al., 2009).

While a good proposal is persuasive, accurate and complete, most proposals do not provide these qualities (Sant, 2012). Various definitions for project success other than the traditional criteria have been used (Bakker et al., 2010; DeLone & McLean, 1992, 2003; Savolainen et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2018). A project may be considered successful if it met the traditional constraints but may not have met user, customer, or other stakeholders’ requirements (Baker et al., 1997). A comprehensive definition of project success must therefore reflect the different interests and views of all stakeholders, which leads to a multidimensional definition (Dvir et al., 2003; Pinto & Mantel, 1990).

Wallace and Keil (2004) used two constructs adapted from Rai and Al-Hindi (2000) and Nidumolu (1996) to measure project performance: product performance and process performance (Wallace & Keil, 2004). Due to the potential heterogeneity in our respondents, our study focuses on the process performance measure, which assesses if the project was delivered by the project team within the estimated schedule and cost (Nidumolu, 1996; Rai & Al-Hindi, 2000). However, in the post-hoc section of our paper, we also provide a test of product performance (Wallace & Keil, 2004).

On the way to project completion, project execution is subject to unpredictable risks; of these, requirements risk is considered particularly important (Boehm, 1991). The success of an RFP depends not only on its own efforts, but also on the requirements risks produced by interactions with stakeholders (e.g., misunderstandings and changes of intentions or information asymmetry) (e.g., Tabassum et al., 2024; Chu et al., 2022). Requirements risk is defined by three factors: (1) lack of frozen requirements: as the needs of users change, requirements change, thus causing delays; (2) misunderstanding the requirements: not thoroughly defining and/or not understanding the true work effort, skill sets, and technology required to complete the project; and (3) new or unfamiliar subject matter for both users and developers: lack of domain knowledge leads to poor requirements definition (Wallace & Keil, 2004).

Many studies that have examined the relationship between risk and performance (Han & Huang, 2007; Jiang & Klein, 2000; Keil et al., 2013; Liu, 2016; Liu & Wang, 2014; Nidumolu, 1995, 1996; Wallace et al., 2004a; Zhang et al., 2018) show that the risk factors of a project should be identified and managed in order for projects to achieve their objectives. Thus, the identification and management of risk factors play a crucial role in project success and performance (Menezes et al., 2019). In a meta-analysis of project success factors, requirements were the top cited factor of project risk (Bakker et al., 2010) and have been shown to have a negative relationship with project performance (Nidumolu, 1995, 1996; Keil et al., 2013). Accordingly, we propose this main effect as our baseline hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 Requirements risk will be negatively associated with project performance.

When discussing the benefits of proposal overlap, we draw on TMS, a system of cognitive interdependence conceived of by Wegner (1987), who observed that members of long-tenured groups tended to rely on each other to obtain, process, and communicate information from different knowledge domains (Brandon & Hollingshead, 2004). Transactive memory exists among individuals of a project team as a function of their individual memories (Lewis, 2003; Hsu et al., 2012; Carmeli et al., 2021). According to TMS, individuals who are interdependent can identify, locate, and leverage the expertise of others to complement their own knowledge, thereby mitigating knowledge redundancy, expanding differentiated collective intelligence, and utilizing this knowledge to formulate integrated solutions to problems (Lewis, 2003; Wegner, 1987; Moh’d et al., 2021). TMS relies on each member’s knowledge of “who knows what” and “who does what,” as well as methods for learning, remembering, and communicating this information (Argote & Ren, 2012; Lewis, 2003; Wegner, 1987; Wegner et al., 1985).

Teams with a more developed TMS are likely to perform at higher levels than teams with a less developed TMS (Lewis & Herndon, 2011; Jarvenpaa & Keating, 2011). TMS makes it easy and quick to access specialized knowledge, allowing more expertise to be effectively applied to project tasks. Research has shown that TMS significantly and positively impacts task performance and facilitates the use of expertise and learning (Akgün et al., 2005; DeChurch & Mesmer-Magnus, 2010; Hollingshead, 1998a, 1998b; Wang et al., 2018).

Studies have also shown that TMS can help organizational teams perform well and may provide benefits across a variety of team contexts (Lewis, 2003, 2004; Lewis et al., 2007). For example, as information search is faster, members can apply knowledge more quickly and adapt more quickly to project risks (Lynn et al., 2000). Important information for tasks is less likely to be forgotten or missed because it can be effectively assigned to appropriate team members. Relying on teammates for specific areas of expertise boosts the knowledge available to the team, which in turn enhances overall performance (Bachrach et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2014; Lewis & Herndon, 2011). TMS enables team members both to anticipate one another’s actions and to fully utilize the expertise that is essential to team performance (DeChurch & Mesmer-Magnus, 2010).

TMS theory is predicated on the expectation that individuals in close relationships accomplish collective tasks by dividing responsibility for learning, remembering, and communicating different but complementary information (Wegner, 1987; Wegner et al., 1985). Team members rely on one another to be responsible for specific expertise such that, collectively, they possess all of the information needed for their tasks. Mutual reliance frees individual members to develop deeper expertise in specialty areas, while still ensuring access to others’ information, so that a greater amount of expertise can efficiently be brought to bear on project tasks (Lewis, 2003). Information needed during task processing can be collected from team members as appropriate, thus increasing the amount and quality of information available to teams and increasing performance on information-intensive tasks (Bachrach et al., 2019; Moreland, 1999).

As projects are multifaceted (Akgün et al., 2004), interpretation of buyer requirements as stated in the RFP is performed by the proposal team members according to their functional areas of expertise. For example, a specialist in software design would interpret the software requirements while a hardware specialist would interpret the hardware requirements; working together, they will develop a competitive solution for the buyer. Each specialist is responsible for their area of the proposal as well as the combined integrated solution. Trade-off decisions involving cost, schedule, and quality in order to remain competitive are made by the proposal development team.

In related research, the benefits of TMS have been stressed for product development teams (Akgün et al., 2005). Here, not only are information access, storage, and integration important, TMS can serve as a means of educating new members of the team (Koufteros et al., 2002; Paul et al., 2004). The latter is of particular importance; when people roll off from the RFP, new members of the final project execution team can be better brought up to speed and ambiguity and information asymmetry can be minimized.

Studies have shown that memory overlap can facilitate enterprise development (Wu et al., 2023; Giacosa et al., 2023). If the proposal development team remains intact during project execution, there is minimal TMS disruption and requirements risk is reduced. Continuation of the structure allows the team to know who does what and who is good at their specialty. But, due to the dynamic allocation of personnel to available projects, there is no guarantee that the proposal development team will be assigned to the project execution team once the buyer has approved the proposal (Lewis, 2004; Lewis et al., 2007). Losing a team member disrupts TMS and reduces team productivity (Lewis et al., 2007), thus increasing project risk and reducing performance, as the TMS structure of the final team must now be rebuilt. The higher the proposal overlap, the lower the disturbance and the smoother the process. Accordingly, a disrupted TMS structure increases requirements risk and negatively affects process performance, which leads to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2 As the number of team members that work on both the proposal development team and the project execution team increases (proposal overlap), the negative relationship between the project’s requirements risk and process performance is reduced.

To ensure that enough data for analysis would be available, we used four methods of data collection. In the first method, we acquired survey data using Qualtrics (www.qualtrics.com), an organization that not only provides survey tools but also will distribute the survey at a cost. The surveys distributed by Qualtrics (160) were restricted to only project managers. In the second method, we surveyed project managers within a division of a high-tech company. We sent three emails approximately every two weeks to 255 project managers (56 surveys were started, 36 were successfully completed). For the third method, we contacted existing or retired project managers who had been in the network of the author (18 surveys were started, 12 were successfully completed).

In the fourth method, we utilized 149 local chapters of the Project Management Institute (PMI) located within the United States. The board of directors of 27 local chapters were contacted by email and with a follow-up letter regarding distribution of the survey to their membership (six chapters responded; other chapters may have distributed the survey without notifying the author). To distribute the survey, an email was sent to chapter members and links were included in the PMI monthly chapter newsletter, on their website, and on their LinkedIn or Facebook page.

In addition to the board contact, every local chapter was contacted regarding allowing a link to be placed on their LinkedIn page. Sixty-seven chapters agreed to this request; some links were placed twice depending on the date of the chapter’s approval. A LinkedIn connection with the author was requested of the board members, directors, and volunteers of the chapter whose name appeared on the website. Once that connection was established, a request to complete the survey was issued via a LinkedIn message. Approximately 1450 LinkedIn connections were established and survey requests generated (317 surveys were started, 295 were successfully completed).

We controlled for the respondent’s source to mitigate any potential biases. The sample consisted of multifunctional members of project teams including project managers, financial controllers, procurement staff, sub-contractors, and developers; however, the study primarily focused on current and former project managers. Furthermore, respondents were asked to evaluate the last project that they completed (Keil et al., 2013; Wallace et al., 2004a). Prior to deployment, we asked multiple respondents from different project functions to review the survey to ensure that the questions were being interpreted correctly. No concerns were noted and the full survey was then deployed.

MeasurementDependent Variable. The dependent constructs of interest are based on the project performance scales developed by Nidumolu (1995) and used by Wallace et al. (2004a). Project performance consists of two reflective constructs: process performance and product performance. We utilized process performance, which refers to the extent the project was completed within the estimated budget and schedule, as it is more universally applicable and relates more directly to requirements risk. The process performance construct consists of two items measured using a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 7 = Strongly Agree). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.775. All items of our multi-item constructs are listed in the Appendix; all were utilized in creating the constructs and calculating the alphas.

Independent Variable. The independent construct of interest was based on the project risk scales developed by Wallace et al. (2004a), which consist of six reflective constructs: requirements risk, project complexity risk, user risk, organizational risk, planning and control risk, and team risk. This study concentrated on requirements risk, which consists of four items measured using a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = Strongly Disagree = 1 to 7 = Strongly Agree). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.832.

Moderator.Proposal overlap is defined as the percentage of team members who worked on both the proposal team and the execution team. This percentage includes subcontractors, consultants, customers, and users. Sample values ranged from 0 % (no overlap) to 100 % (the complete proposal development team was also part of the project execution team). The mean was 30.49 with a standard deviation of 30.83.

Controls. Controls were based upon previous studies as well as additional controls deemed relevant for this study. Eleven dummy variables represented the primary industry receiving the project service, deliverable, or outcome, as each industry may have different norms that may affect the perception dependent variable. Industry was defined as follows: Manufacturing, Finance, Education, Retail, Media, Government – non-Defense, Government - Defense, Utilities, Healthcare, Construction, and Transportation. Respondents’ primary functions were grouped as follows: project management (Func PM), executive management (Func EM), and “other (Func Other).” As the function variable was dummy-coded, EM served as the omitted group.

We further controlled for the source of the survey data in order to avoid any bias stemming from the source of data collection. Table 1 contains the characteristics of the survey data. As the size of the project team could affect project risk and performance, the percentage of individuals external to the division or organization (e.g., consultants, subcontractors) has been shown to be an important control variable (Rai & Al-Hindi, 2000; Zhang et al., 2018), hereafter referred to as subcontractor percentage. We further controlled for the elapsed time between project proposal and execution. Longer duration leads to higher project risk, as client requirements tend to be highly fluid and any shifts over time may have significant impact on the perceived outcome (Yeow & Chua, 2012).

In addition, we controlled for four demographic variables common to project management studies. The first two are age and gender and experience (in years) in that role (Keil et al., 2013; Wallace et al., 2004a; Wang et al., 2008). We also controlled for type of project, which consisted of three dummy variables: ProjServ (Service), ProjRD (R&D), ProjProd (Product or application). Last, we controlled for project duration, an important reflection of the overall complexity of a project. A summary of all variables is listed in Table 2.

Summary of all variables.

| Variable | Category | Definition | Abbreviations of Variables used inTable 2and3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | Industry | Primary industry receiving the project service, deliverable, or outcome | Industry1 (Manufacturing) |

| Industry2 (Finance) | |||

| Industry3 (Education) | |||

| Industry4 (Wholesale / Retail) | |||

| Industry5 (Media, Entertainment) | |||

| Industry6 (Gov. – non-defense) | |||

| Industry7 (Gov. – defense) | |||

| Industry8 (Utilities) | |||

| Industry9 (Health Care) | |||

| Industry10 (Construction) | |||

| Industry11 (Transportation) | |||

| Function | Respondents’ primary function | Func PM | |

| Func Other | |||

| Func EM | |||

| Size | Size of the project | Size | |

| Gender | Gender of the respondents | Gender | |

| Source | Dummy variables from different sources of the sample | Source - PMI | |

| Source - High Tech | |||

| Source - Other | |||

| Age | Age of the respondents | Age | |

| Experience | Experience of the respondents | Experience | |

| Education | Education of the respondents | Education | |

| Type | Types of project | Proj Service (Service) | |

| Proj R&D (R&D) | |||

| Proj Prod (Product / Application) | |||

| Duration | The duration of the project | Proj Duration | |

| Subcontractor | Percentage of individuals external to the division or organization | SubC percent | |

| Independent Variable | Requirement Risk | Requirements risk of the project | Requirement Risk |

| Moderator | Proposal Overlap | Percentage of team members who worked on both the proposal team and the execution team | Proposal Overlap |

| Dependent Variable | Project Performance | The extent the project was completed within the estimated budget and schedule | Project Performance |

The survey was designed so that a respondent must answer a question before continuing with the next question. A survey was considered incomplete if all of the questions were not answered. Only fully completed surveys were used in the data analysis. All analysis was performed using SPSS. A reliability analysis was performed to evaluate the multi-item scale by assessing scale reliability as measured by the coefficient alpha. Alpha values ranged from 0.0 to 1.0, with unacceptable values less than 0.70 (Peterson & Kim, 2013). All alphas were above the threshold and considered satisfactory. The descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations between the variables are provided in Table 3; regression results are portrayed in Table 4.

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations1.

| Variables | Mean | Std | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Industry1 (Manufacturing) | 0.13 | 0.34 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Industry2 (Finance) | 0.13 | 0.33 | −0.150⁎⁎ | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | Industry3 (Education) | 0.06 | 0.23 | −0.095* | −0.093* | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | Industry4 (Wholesale / Retail) | 0.06 | 0.28 | −0.099* | −0.096* | −0.061 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | Industry5 (Media, Entertainment) | 0.38 | 0.19 | −0.078 | −0.076 | −0.048 | −0.050 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | Industry6 (Gov. – non-defense) | 0.06 | 0.23 | −0.097* | −0.094* | −0.060 | −0.062 | −0.049 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | Industry7 (Gov. – defense) | 0.10 | 0.30 | −0.130⁎⁎ | −0.127⁎⁎ | −0.081 | −0.084 | −0.066 | −0.082 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | Industry8 (Utilities) | 0.08 | 0.27 | −0.112* | −0.109* | −0.069 | −0.072 | −0.057 | −0.071 | −0.095* | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 | Industry9 (Health Care) | 0.13 | 0.34 | −0.154⁎⁎ | −0.150⁎⁎ | −0.095* | −0.099* | −0.078 | −0.097* | −0.130⁎⁎ | −0.112* | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 | Industry10 (Construction) | 0.05 | 0.23 | −0.093* | −0.091* | −0.058 | −0.060 | −0.047 | −0.059 | −0.079 | −0.068 | −0.093* | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 11 | Industry11 (Transportation) | 0.28 | 0.16 | −0.066 | −0.065 | −0.041 | −0.043 | −0.034 | −0.042 | −0.056 | −0.048 | −0.066 | −0.040 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | Func PM | 0.77 | 0.42 | 0.004 | 0.023 | −0.012 | 0.017 | 0.058 | −0.008 | 0.054 | −0.203⁎⁎ | 0.032 | 0.088* | 0.063 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 13 | Func Other | 0.15 | 0.36 | 0.028 | −0.063 | −0.031 | −0.014 | −0.026 | −0.034 | −0.031 | 0.192⁎⁎ | −0.020 | −0.077 | −0.072 | −0.781⁎⁎ | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| 14 | Func EM | 0.45 | 1.59 | −0.046 | 0.049 | 0.062 | −0.008 | −0.057 | 0.058 | −0.045 | 0.061 | −0.024 | −0.035 | −0.003 | −0.525⁎⁎ | 0.122⁎⁎ | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 15 | Size | 93.48 | 288.41 | −0.028 | −0.039 | −0.038 | −0.003 | −0.026 | 0.042 | 0.035 | −0.051 | 0.008 | 0.047 | 0.010 | −0.052 | 0.034 | 0.037 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| 16 | Gender | 1.45 | 0.56 | 0.096* | −0.086 | −0.067 | −0.016 | 0.069 | 0.011 | 0.064 | 0.099* | −0.163⁎⁎ | 0.085 | −0.022 | −0.087 | 0.006 | 0.130⁎⁎ | −0.004 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 17 | Source - PMI | 0.59 | 0.49 | 0.056 | 0.030 | −0.025 | −0.044 | −0.045 | 0.000 | −0.031 | 0.011 | 0.056 | −0.212⁎⁎ | −0.005 | −0.198⁎⁎ | 0.155⁎⁎ | 0.103* | −0.043 | −0.005 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 18 | Source - High Tech | 0.07 | 0.26 | −0.086 | −0.083 | −0.067 | −0.070 | −0.055 | 0.097* | 0.088* | 0.329⁎⁎ | −0.086 | −0.066 | −0.047 | −0.179⁎⁎ | 0.182⁎⁎ | 0.037 | 0.061 | 0.119⁎⁎ | −0.331⁎⁎ | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 19 | Source - Other | 0.24 | 0.15 | −0.023 | 0.058 | −0.038 | 0.016 | −0.031 | −0.039 | 0.079 | −0.045 | 0.015 | 0.021 | −0.026 | −0.194⁎⁎ | 0.078 | 0.202⁎⁎ | 0.019 | 0.058 | −0.186⁎⁎ | −0.043 | 1 | |||||||||||

| 20 | Age | 48.62 | 11.40 | −0.032 | 0.030 | −0.044 | −0.037 | −0.033 | 0.065 | 0.127⁎⁎ | 0.017 | 0.009 | −0.073 | 0.010 | −0.109* | 0.113* | 0.019 | 0.031 | 0.151⁎⁎ | 0.219⁎⁎ | 0.006 | 0.041 | 1 | ||||||||||

| 21 | Experience | 15.22 | 9.18 | 0.016 | 0.056 | −0.003 | −0.028 | 0.085 | 0.065 | 0.066 | −0.010 | −0.089* | −0.002 | −0.032 | −0.020 | 0.073 | −0.068 | 0.126⁎⁎ | 0.181⁎⁎ | 0.052 | −0.003 | 0.043 | 0.583⁎⁎ | 1 | |||||||||

| 22 | Education | 5.91 | 1.45 | −0.040 | 0.106* | 0.063 | −0.141⁎⁎ | −0.088* | 0.021 | 0.030 | 0.101* | 0.008 | −0.180⁎⁎ | −0.040 | −0.187⁎⁎ | 0.110* | 0.147⁎⁎ | 0.010 | 0.015 | 0.282⁎⁎ | 0.044 | 0.073 | 0.188⁎⁎ | 0.062 | 1 | ||||||||

| 23 | Proj Service (Service) | 0.34 | 0.48 | −0.062 | −0.038 | −0.030 | −0.041 | 0.010 | 0.018 | −0.017 | −0.017 | 0.024 | 0.032 | 0.005 | −0.004 | −0.006 | 0.015 | 0.012 | 0.036 | −0.114* | −0.022 | 0.079 | −0.014 | −0.006 | −0.111* | 1 | |||||||

| 24 | Proj R&D (R&D) | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0.119⁎⁎ | −0.023 | 0.010 | 0.005 | −0.051 | −0.028 | 0.025 | −0.042 | 0.021 | −0.061 | 0.007 | 0.061 | −0.063 | −0.011 | 0.026 | −0.058 | −0.121⁎⁎ | −0.007 | −0.040 | −0.033 | 0.042 | 0.056 | −0.186⁎⁎ | 1 | ||||||

| 25 | Proj Prod (Product / Application) | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.039 | 0.034 | 0.033 | 0.066 | 0.009 | 0.041 | 0.025 | 0.028 | −0.043 | 0.007 | −0.049 | 0.027 | −0.041 | 0.013 | −0.079 | 0.041 | 0.102* | −0.017 | −0.053 | −0.020 | −0.033 | 0.032 | −0.728⁎⁎ | −0.258⁎⁎ | 1 | |||||

| 26 | Proj Duration | 14.67 | 15.79 | −0.018 | −0.061 | −0.048 | −0.093* | −0.025 | 0.104* | 0.122⁎⁎ | 0.105* | −0.033 | −0.057 | 0.143⁎⁎ | −0.077 | 0.001 | 0.121⁎⁎ | 0.301⁎⁎ | 0.085 | 0.125⁎⁎ | 0.156* | −0.028 | 0.188⁎⁎ | 0.067 | 0.131⁎⁎ | −0.004 | 0.014 | −0.023 | 1 | ||||

| 27 | SubC percent | 31.45 | 31.30 | −0.032 | 0.047 | −0.079 | 0.072 | −0.091* | 0.048 | −0.037 | 0.060 | −0.067 | 0.110* | −0.012 | −0.033 | 0.045 | −0.008 | 0.218⁎⁎ | 0.015 | 0.075 | −0.082 | 0.018 | 0.089* | 0.071 | 0.044 | −0.029 | −0.024 | 0.022 | 0.095* | 1 | |||

| 28 | Requirement Risk | 4.15 | 1.47 | −0.003 | 0.023 | −0.041 | 0.016 | −0.058 | −0.030 | 0.061 | −0.031 | −0.033 | 0.011 | 0.090* | −0.058 | 0.002 | 0.082 | 0.080 | 0.007 | 0.094* | −0.026 | 0.079 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.070 | −0.015 | −0.079 | 0.063 | 0.100* | 0.151⁎⁎ | 1 | ||

| 29 | Proposal Overlap | 30.49 | 30.83 | −0.060 | −0.010 | −0.078 | 0.054 | 0.038 | −0.015 | 0.072 | −0.028 | −0.053 | 0.132⁎⁎ | −0.019 | 0.114* | −0.080 | −0.083 | −0.007 | −0.028 | −0.301⁎⁎ | −0.100* | −0.024 | −0.083 | −0.040 | −0.047 | 0.054 | 0.114* | −0.031 | −0.039 | 0.166⁎⁎ | −0.054 | 1 | |

| 30 | Project Performance | 2.94 | 1.65 | −0.048 | −0.021 | 0.065 | −0.017 | 0.050 | −0.012 | −0.010 | −0.063 | 0.071 | 0.096* | 0.005 | 0.158⁎⁎ | −0.141⁎⁎ | −0.058 | −0.079 | −0.005 | −0.284⁎⁎ | 0.044 | −0.002 | −0.060 | −0.023 | −0.075 | 0.132⁎⁎ | 0.011 | −0.092* | −0.125⁎⁎ | −0.157⁎⁎ | −0.357⁎⁎ | 0.181⁎⁎ | 1 |

N = 503.

Regression analysis.

| Dependent Variable: Project Performance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Variables1 | β | β | β | β |

| Controls | ||||

| Industry1 (Manufacturing) | .014 | .016 | .017 | .015 |

| Industry2 (Finance) | .025 | .027 | .024 | .022 |

| Industry3 (Education) | .069 | .059 | .050 | .055 |

| Industry4 (Wholesale / Retail) | .014 | .019 | .014 | .023 |

| Industry5 (Media, Entertainment) | .044 | .033 | .027 | .027 |

| Industry6 (Gov. – non-defense) | .023 | .007 | .005 | .007 |

| Industry7 (Gov. – defense) | .021 | .038 | .025 | .018 |

| Industry8 (Utilities) | -0.003 | -0.020 | -0.026 | -0.031 |

| Industry9 (Health Care) | .103 | .096 | .096 | .099 |

| Industry10 (Construction) | .075 | .081 | .074 | .073 |

| Industry11 (Transportation) | .025 | .055 | .055 | .056 |

| Func PM | .051 | .023 | .022 | .023 |

| Func Other | -0.044 | -0.068 | -0.073 | -0.072 |

| Size | -0.042 | -0.031 | -0.026 | -0.020 |

| Gender | .012 | .006 | .007 | .003 |

| Source - PMI | -0.256⁎⁎⁎ | -0.225⁎⁎⁎ | -0.180⁎⁎⁎ | -0.176⁎⁎ |

| Source - High Tech | .000 | .010 | .037 | .038 |

| Source - Other | -0.050 | -0.026 | -0.013 | -0.005 |

| Age | .031 | .007 | .008 | .017 |

| Experience | -0.005 | .006 | .010 | .014 |

| Education | .049 | .064 | .054 | .059 |

| Proj Service (Service) | .102 | .123 | .109 | .104 |

| Proj R&D (R&D) | -0.009 | -0.021 | -0.034 | -0.027 |

| Proj Prod (Product / Application) | -0.006 | .027 | .016 | .022 |

| Proj Duration | -0.072 | -0.054 | -0.058 | -0.058 |

| SubC percent | -0.113* | -0.054 | -0.092* | -0.091* |

| Independent Variable | ||||

| Requirement Risk | -0.321⁎⁎⁎ | -0.317⁎⁎⁎ | -0.311⁎⁎⁎ | |

| Moderator | ||||

| Proposal Overlap | .119⁎⁎ | .118⁎⁎ | ||

| Interaction | ||||

| Requirement Risk * Proposal Overlap | .114⁎⁎ | |||

| R2 | .145 | .240 | .249 | .262 |

| Adjusted R2 | .098 | .197 | .205 | .216 |

| Delta R2 | .145 | .095 | .009 | .012 |

| F | 3.097⁎⁎⁎ | 59.591⁎⁎⁎ | 5.911⁎⁎ | 7.906⁎⁎ |

N = 503.

In order to test our two hypotheses, we used multiple regression analysis with four models (Table 4). In Model 1, control variables were entered. In Model 2, the main effect was entered. The moderator, overlap, was entered in Model 3; in Model 4, the respective interaction was entered. The VIF and Condition index values were below the recommended guidelines for all variables (Hair et al., 2010). In Model 1, subcontractor percentage was significantly and negatively related to project performance (β=−.113, p<.05). Control for the responses submitted by members of the local PMI chapters, IDDummy1 (PMI), was significantly and negatively related to project performance (β=−.256, p<.001). The model was significant (p<.001), with an adjusted R2 of 0.098.

To test Hypothesis 1, Model 2 included the independent variable, requirements risk. Hypothesis 1 proposed that as requirements risk increased, project performance would be negatively impacted. Requirements risk was significantly and negatively related to project performance (β=−.321, p<.001). The model was significant (p<.001); the adjusted R2 of 0.197 suggests that as requirements risk increased, project performance decreased, supporting Hypothesis 1. Model 3 included the moderator, overlap. Overlap was significantly and positively related to project performance (β=0.119, p<.01). The model was significant (p<.01), with an adjusted R2 of 0.205.

To test Hypothesis 2, the interaction between the moderator, overlap, and the independent variable, requirements risk, was included in Model 4. Hypothesis 2 proposed that as overlap increased, requirements risk would decrease and project performance would increase. The interaction was significantly and positively related to project performance (β=0.114, p<.01). The model was significant (p<.01), with an adjusted R2 of 0.216 and a delta R2 of 0.012. The interaction is plotted in Fig. 3, which shows that at higher risk, process performance decreased. This effect was mitigated when a high overlap between project proposal and execution team members occurred, supporting Hypothesis 2.

Post-hoc and bias testIn our main analysis, we focused only on requirements risk; we did not include organizational environment, user, project complexity, planning and control, or team risk (additional risk types identified by Wallace & Keil (2004). We did so in order to avoid potential multicollinearity. However, as different types of risk often work in concert, focusing on one type of risk may overestimate its effects. Accordingly, we reran our analysis and included the remaining five risk types as additional control variables. Requirements risk remained marginally significant (β=−.112, p<.10) in Model 2. Only planning and control risk was significant (β=−.291, p<.001). In Model 4, the interaction effect remained significant at 0.108 (p <0.01), thus stressing the importance of our chosen moderator. In a further step, we then linked our moderator with all risk types. Only the interaction with requirements risk was marginally significant (β=0.114, p<.10), again showing the particular importance of this moderator.

In a second step, we reran the model with product performance as a dependent variable (alpha = 0.832). We ran this twice, first as a replication of the main models reported in our analysis. Here, requirements risk was significant in Model 2 (β=−.356, p<.001) and the interaction was significant in Model 4 (β=0.103, p<.05). In the second rerun, we included the other five risk types. Here, planning and control risk was significant in Model 2 (β=−.295, p<.001) and team risk was marginally significant (β=−.107, p<.10). Although requirements risk became insignificant as the main effect, the interaction effect remained highly significant (β=0.121, p<.01), again stressing the power of the moderator.

Researchers agree that common method variance (CMV) is a potential problem in behavioral research, as it is attributable to the methods of measurement rather than the constructs the measures represent (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Using a survey to collect data can generate CMV bias based on 1) collection of data at a single point in time, 2) single respondents of a project, 3) self-evaluation of performance, and 4) respondent recall. Yet, a survey is often the preferred way to collect and analyze large-sample data for testing hypotheses due to the potential cost and time limitations of other data collection methods (Nidumolu, 1996).

To determine if CMV was present, we used the Harmon single-factor test. All of the items for the independent, moderator, control, and dependent variables were entered into a factor analysis. There were 16 factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.0, which accounted for 71.99 % of the variance; the highest variance was 8.94 %. Since no single factor accounted for the majority of variance, common method bias was unlikely to occur (Podsakoff et al., 2012).

DiscussionThrough our large-scale empirical analysis, we found support for Hypothesis 1, which proposed that requirements risk will have a negative impact on project performance. We further found support for Hypothesis 2, which proposed that as the number of members that work on both the proposal and execution teams increases, the negative relationship between requirements risk and process performance would decrease. Our post-hoc test showed support for this relationship when product performance was utilized as a dependent variable, suggesting consistent relationships across different dependent variables.

Our findings stress the risk-mitigating effects of proposal overlap, highlighting the power of TMS (Antunes & Pinheiro, 2020; Ode & Ayavoo, 2020; Guo et al., 2022; Argote & Guo, 2016; Lewis, 2003; Lewis & Herndon, 2011; Wang et al., 2018; Wegner, 1987). We argued for and received strong empirical support that knowledge stored through transactive memory can be accessed in cases of overlapping members between the RFP and execution team, as the flow and transfer of knowledge is less interrupted by team member turnover. Thus, our findings demonstrate the usefulness of TMS in the execution of projects involving multi-agent interaction and provide a governance-level solution to risk mitigation problems in the RFP process.

ConclusionThe proposal procurement process is used worldwide by industry and all levels of government (Meier, 2008; Searcy, 2009). Despite their ubiquity, projects are rarely developed on schedule, within budget, or meet user expectations, with only a 29 % chance of successful completion (Abdullah & Verner, 2012). We have shown that increasing the overlap between the proposal development and project execution team members can reduce the negative relationship between project requirements risk and process performance, thus improving project performance. As we are one of few studies to empirically analyze the linkage between RFP and project execution, we hope that our findings encourage researchers to examine the linkages between RFP and project performance and help practitioners realize more successful execution.

Managerial implicationsThis study provides additional empirical evidence for the relationship between risk and performance, answering the call in the literature for more research on project risk (Liu, 2016). We show that requirements risk is a major contributor to decreasing process and, based on the post-hoc test, product performance. Few studies have investigated the link between project risk and project performance (for exceptions see Bakker et al., 2010; Bannerman, 2008; Liu et al., 2009; Taylor et al., 2012; Wallace et al., 2004b). Our focus on the RFP process using a large-scale sample of 503 respondents has broken new ground in the literature.

We furthermore expand project management risk theory. Not only did we show the interdependence between RFPs and project execution, by incorporating TMS (Argote & Ren, 2012; Lewis, 2003; Wegner, 1987; Wegner et al., 1985), we provide a solid theoretical foundation for future research that can build on our findings related to proposal overlap. Our study shows that a holistic process that spans from RFP to project execution is necessary to fully understand project (product) performance, mitigate risk, and enhance knowledge transfer and flow across stages of the proposal process.

Practical implicationsOur research focuses on project management practices. As the link between RFP and project execution and, ultimately, project performance is still not well understood, practical, easily manageable tools are necessary for practitioners to enhance performance. Because requirements can significantly and negatively affect performance, the project team must ensure that requirements are adequately identified, clearly defined, all accounted for, and correct. As required for PMI training and certification, requirements should be defined during the early phases of a project (Project Management Institute, 2018). Otherwise, the cost of redoing completed portions of the project to meet these requirements can be substantial; they are the hardest to fix or resolve after the fact (Boehm, 1991).

Moreover, as the number of subcontractors and consultants increases, project risk escalates, adversely impacting project performance. Consequently, it is advisable to prioritize the utilization of in-house employees over external consultants and subcontractors. As our findings show, fostering overlap between members of the project proposal and execution teams should be encouraged to mitigate the detrimental effects of requirements-related risks on overall performance. Proposal overlap can thus be a salient and usable tool that is easy to implement and effective in practice (Bakker et al., 2010; Bannerman, 2008; Taylor et al., 2012).

Limitations and future researchWe relied on self-reported data and a single respondent design, necessitating that our findings need to be interpreted cautiously and that future studies replicate them. Indeed, our findings may have been subject to recall bias as the survey required respondents to reconstruct their project experience (Akgün & Lynn, 2002; Avolio et al., 1991; Gupta & Beehr, 1982). This bias was reduced, to some extent, by collecting data on the most recently completed project (Keil, 2013; Nidumolu, 1996). While the use of single respondents is prevalent in academic research, it would have been more advantageous to include multiple respondents from each RFP team and collect objective data for our outcome variable. In addition, as the study was cross-sectional in nature, we also checked for common method bias, which did not show any cause for concern (Podsakoff et al., 2003).

Second, the majority of respondents were managers, which may have resulted in a one-sided evaluation (Barki, 2001). Even though the distribution of the variables measured were neither skewed nor centered near the top of the range, which could be indicative of bias, this potential should be recognized (Jiang, 2001). To help reduce bias, studies should include project team members with different functional expertise (e.g., financial, technical, quality assurance). Furthermore, our measure of proposal overlap does not take the quality aspects of team member involvement or their specific roles in both phases into account. While such information would potentially require complex study designs, such research could benefit from network theory related insights (e.g., Burt, 2004. Levin et al., 2011; Manteli et al., 2014). Alternatively, a scale development effort that captures the quality of overlap interactions could also be highly desirable.

Developing a proposal requires trade-offs to be made between cost, schedule, and requirements by the proposal development team (Chen, 2009; Nidumolu, 1996). The empirical investigation of whether these trade-offs exacerbate risks associated with the proposal and impact project performance is essential. While we focused on requirements risk, our post-hoc analysis showed that our findings also hold for product performance. Accordingly, proposal overlap is an important moderator in the relationship between requirements risk and both commonly used performance variables (i.e., Wallace et al., 2004a). Yet, our post-hoc analysis also showed that only a few of the risk dimensions had performance-related outcomes (i.e., planning and control risk). Thus, while project risk is multidimensional, the measures are still broad; failure to establish more significance may be related to conceptualization. Researchers may want to develop more fine-grained measures for each of the risk types identified by Wallace et al. (2004a).

Exploring the mechanism of proposal overlap in the view of different risks may further help us to discover different boundary conditions of TMS theory in enterprise project management. Complementing TMS with insights from agency theory, particularly the lens of multi-agent interactions (e.g., Fleckinger et al., 2024), may be a fruitful avenue.

Furthermore, additional risk factors need to be taken into account. For example, research could include political involvement in projects, where decisions are frequently made for reasons unrelated to successful project execution. For instance, requirements may be added without corresponding increases in cost or schedule, or there may be attempts to shorten the project timeline. Therefore, examining the impact of changes in the external institutional context and the market context on the mechanism of proposal overlap may be worthwhile.

Prioritizing customer satisfaction to secure future business opportunities for the supplier is a common practice in the RFP process that can lead to a decline in process performance. Accordingly, the type of dependent variable utilized needs to be carefully considered, with even a balanced scorecard approach being utilized (e.g., Kaplan & Norton, 1996).

In addition, while the examination of project risk and performance has predominantly concentrated on individual projects, it is essential to also investigate the interconnections between multiple projects (Teller, 2013; Tikkanen et al., 2007); for example, the process of knowledge transfer that encompasses the relationships between projects within the organization as well as those between projects operating under the new management framework and processes. While portfolio theory has concentrated on the distribution of the firm’s scarce resources to projects within a portfolio, there has been a lack of investigation of how risk factors affect linkages between projects (Tikkanen et al., 2007). Examining these linkages might improve the amount of scarce resources available within a firm since risk may be reduced and project performance improved.

For each RFP, there is a winner and one or more losers. As some firms have a very successful record when competing in the procurement process, the factors that contribute to successful procurement could be investigated. Another aspect of procurement is the re-compete process (Smith et al., 2022), which occurs when a contract is up for renewal and the incumbent is competing with other firms to win the contract. Does the incumbent have the advantage? What factors make for a successful defense of contract re-compete? We also encourage investigation of the procurement process when a contract is designated for only small businesses. Do contracts designated for a specified group actually support that group? Such examinations would be a great benefit to industries that must compete in the procurement process.

FundingThe research is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China Key Program Project (72532008).

CRediT authorship contribution statementXin Gao: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. Lawrence Haynes: Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Franz W. Kellermanns: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

1All items are utilized in calculating the Alpha