Rapid technological advancements, innovation, shifting job market demands, and organizational change have made continuous learning and skill development essential for leadership success. Higher education institutions (HEIs) are expected to play a critical role in preparing future leaders; however, many HEIs lack structured pathways for leadership upskilling within their curricula. Leadership education often remains largely theoretical, leaving graduates underprepared for real-world leadership challenges. This qualitative study explores how leadership upskilling is structured in U.S. HEIs by conducting interviews with 18 directors of leadership programs. The findings underscore the key strategies employed by HEIs, including adaptability training, real-world experiential learning, mentorship initiatives, and partnerships with external organizations. Despite increasing awareness of the need for leadership upskilling, empirical research on its implementation in HEIs remains limited. This study addresses that gap and offers targeted recommendations for faculty, administrators, and policymakers on embedding structured skill development into leadership education. By integrating more applied and collaborative upskilling approaches, HEIs can better equip students to navigate complex, rapidly changing professional environments and assume leadership roles in the 21st-century workforce.

The notion of “learn once, work forever” is becoming obsolete in today’s fast-paced job market. Acquiring knowledge early and relying on it throughout one’s career is no longer sufficient to meet the demands of a rapidly evolving, technology-driven economy. The acceleration of technological advancements, innovation, shifting job market requirements, and organizational restructuring have made lifelong learning and continuous skill development essential for success (World Economic Forum, 2025). In this context, employees must actively engage in lifelong learning to develop new skills and competencies needed to remain adaptable in a rapidly changing workplace (Mei et al., 2023; Oberl€ander et al., 2020).

Upskilling, defined as the process of acquiring new competencies or enhancing existing ones to meet changing industry demands, is an essential strategy for higher education institutions (HEIs) responsible for shaping the next generation of leaders (Daher-Armache & Armache, 2024). However, HEIs have traditionally focused on theoretical education and struggled to integrate structured leadership upskilling pathways fully into student development programs (McGunagle & Zizka, 2020). Although existing leadership programs lay the foundation for knowledge acquisition, they often lack the practical skill-building experience, adaptability training, and industry collaboration necessary to develop workforce-ready leaders (Li, 2024).

Global reports underscore an urgent need for HEIs to play a more proactive role in leadership upskilling. The Global Leadership Forecast 2023 emphasize a shortage of leaders equipped to navigate 21st-century challenges, signaling the necessity for HEIs to rethink leadership training models (Development Dimensions International, 2023). Similarly, the Future of Jobs Report 2025 predicts that 39 % of employees’ core skills will change by 2030, making continuous skill development and adaptability essential for student success in leadership roles (World Economic World Economic Forum, 2025). Furthermore, studies indicate that high-potential leaders frequently leave organizations due to a lack of career advancement and professional development opportunities, reinforcing the need for structured upskilling initiatives at the university level (Baranchenko et al., 2020).

The lack of comprehensive leadership, adaptability, and professional preparation programs in HEIs could result in graduates being ill-equipped to assume leadership responsibilities in an increasingly complex and dynamic work environment (Bok, 2020). The ability to navigate complex challenges, leverage technological advancements, and foster innovation requires leaders who are lifelong learners (World Economic Forum, 2025; Yukl & Gardner, 2020). Leadership today extends beyond technical expertise—it demands adaptability, critical thinking, resilience, and ethical decision-making (Daher-Armache & Armache, 2024).

Despite an increasing recognition of the need to equip students with leadership skills that match the demands of today’s rapidly changing workforce, limited empirical research remains on how HEIs integrate leadership upskilling effectively into both academic curricula and co-curricular programming (Ferreira Da Silva et al., 2023). While upskilling has become a prominent focus in workforce development discussions, much of the existing literature and practice have centered on corporate-led initiatives, where organizations design and deliver leadership training tailored to their specific industry needs. These studies provide valuable insights into employer expectations and training models, but often overlook the formative role that HEIs play in shaping students’ leadership competencies before they enter the workforce. As a result, there is a significant gap in the understanding of the strategies HEIs use to embed leadership development into undergraduate and postgraduate education. This includes not only formal coursework but also leadership training through student affairs, extracurricular programs, internships, and experiential learning. Without a clearer understanding of how these initiatives are designed, implemented, and assessed within academic environments, it is difficult to evaluate their effectiveness or ensure they align with the changing needs of the labor market. Addressing this gap is critical for advancing the role of higher education in preparing graduates to lead in complex, interdisciplinary, and digital-first professional environments. Additionally, the voices of leadership program directors who are mainly responsible for shaping and executing these initiatives remain largely absent from academic discourse. Their practical insights into the design, delivery, and challenges of leadership upskilling are essential to fully understand institutional efforts.

Building on this need, this study examines how leadership upskilling should be structured in HEIs to better prepare students for leadership roles in the twenty-first century and what strategies should be implemented to ensure they acquire the necessary leadership competencies for professional success. By analyzing the insights of leadership program directors, this study aims to provide workable recommendations for optimizing leadership upskilling initiatives in HEIs. By carrying out a qualitative investigation, this research identifies best practices and opportunities for embedding upskilling in leadership development programs. The study contributes to the growing literature on higher education leadership education and offers a framework for faculty, administrators, and policymakers to improve leadership training models.

The paper is structured as follows: Section 1 introduces the study. Section 2 presents the literature review and theoretical framework. Section 3 describes the research methodology. Section 4 provides the data analysis and findings. Section 5 discusses the results. Section 6 outlines the theoretical and practical implications. Section 7 discusses the study’s conclusion and limitations and proposes future lines of research.

Literature reviewOrganizations are increasingly driven to continuously generate and apply knowledge to maintain a competitive edge (Dedunu et al., 2025). The prevailing academic perspective suggests that effective knowledge management is crucial for sustaining competitiveness in today’s knowledge-driven environments (Dedunu et al., 2025; Sang, 2024). Education remains a key driver of knowledge acquisition and personal development, equipping individuals with critical thinking and problem-solving skills needed to navigate complex social and economic environments (Li et al., 2025). However, digital transformation in the labor market presents new challenges, particularly by widening inequalities in job access (Martindale & Lehdonvirta, 2023), reinforcing the importance of continuous skill development. Moreover, general knowledge and skills strongly support long-term career mobility (Gronning & Kriesi, 2022), while rapid shifts in labor demands and education policies require workers to consistently upgrade their competencies (Jephcote et al., 2021; Rauscher, 2015).

Innovation today demands collaboration among stakeholders, including partnerships between companies and HEIs (Li et al., 2023; Papa et al., 2020). Furthermore, HEIs are increasingly positioned at the forefront of digital transformation (Li et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2023), and a major challenge is preparing students to meet the evolving demands of the future workforce (Craps et al., 2022; Mei et al., 2023). Industry leaders and policymakers have emphasized the need for HEIs to nurture 21st-century skills essential for professional and personal success (Mei et al., 2023). Nevertheless, many employers report significant gaps in these skills, leading to calls for new educational policies that develop wide-ranging, transferable competencies (Mei et al., 2023). Despite playing a critical role in shaping future talent, many HEIs struggle to keep pace with constant change and innovation, lacking the creativity needed for modern classroom teaching (Lu, 2023). Consequently, finding effective ways to stimulate student motivation and innovative thinking remains a significant challenge (Lu, 2023). Further complicating the landscape, educational inflation, defined as the oversupply of academic degrees, has contributed to the devaluation of diplomas and widened social mobility gaps (Gruijters, 2022). Nonetheless, individuals with stronger skills and higher education credentials remain more proactive in career selection and experience greater professional success (Araki, 2023; Aver et al., 2021; Li et al., 2025; Trinidad et al., 2023).

Lifelong learning has become increasingly important. It represents a continuous, self-motivated pursuit of knowledge for personal and professional development throughout one’s lifetime (Zuo et al., 2025). This learning includes formal and informal pathways, emphasizing adaptability in an ever-changing economy (Zuo et al., 2025). Specifically, lifelong learning enhances employability and supports mobility toward more economically vibrant regions (Li et al., 2025). As higher education continues to expand, concerns grow about its declining impact and the over-reliance on academic credentials, prompting calls for new evaluation systems that prioritize practical skills, adaptability, and innovation (Li et al., 2025). Moreover, lifelong learning is pivotal to addressing the goals of Industry 5.0, fostering innovation, enhancing competitiveness, and promoting social inclusion as we approach 2030 (Rial-Gonzalez et al., 2024; Zuo et al., 2025).

In this context, HEIs must focus on both lifelong learning and leadership development. The traditional education model, where knowledge is acquired early and expected to last throughout one’s career, is no longer sufficient due to rapid technological advances and changing labor market needs (World Economic Forum, 2025). Research urges HEIs to adopt structured leadership training programs to build the competencies needed for success in dynamic environments (Daher-Armache & Armache, 2024). However, leadership education often leans heavily on theory, with insufficient practical application, leaving graduates unprepared for real-world leadership challenges (Bok, 2020).

Employers increasingly seek leaders who can solve complex problems, manage diverse teams, and adapt to constant change (Yukl & Gardner, 2020). Nevertheless, several HEIs still use outdated teaching models that fail to build these capabilities. A global leadership report found that organizations in all sectors struggle to find candidates with the necessary adaptability and problem-solving skills (Development Dimensions International [DDI], 2023). Without integrated leadership development, graduates risk lacking the readiness required for today’s fast-paced workforce (Li, 2024).

Despite their vital role, HEIs face serious challenges to delivering effective leadership education. One critical issue is the rigid academic structure that favors research output over hands-on learning (Bok, 2020). Faculty are often evaluated based on publishing outputs rather than mentoring the next generation of leaders (Rehbock, 2020). This focus results in leadership programs offering limited experiential training (Cavagnaro & Van der Zande, 2021). Furthermore, interdisciplinary collaboration, which is essential for leadership across complex sectors, is often absent from curricula (Friesen, 2020). Moreover, several institutions lack partnerships with industries, limiting students’ exposure to practical leadership experiences. Even though the literature stresses the importance of experiential learning, administrative barriers often prevent its widespread adoption (Balistreri et al., 2012; Bensimon et al., 1989; Rosche et al., 2023).

Human capital theory provides a valuable framework for understanding why leadership development is crucial. It argues that education and skills development increase individuals’ productivity and economic value (Becker, 1964). Thus, leadership competencies are viewed as essential forms of human capital, critical for both individual career success and wider organizational performance (Kouzes & Posner, 2019). Consequently, HEIs should view leadership education as a strategic investment in the future workforce. Without this focus, graduates may fall short in the essential skills for innovation, decision-making, and collaboration (Daher-Armache & Armache, 2024). With 39 % of core job skills predicted to change by 2030 (World Economic Forum, 2025), HEIs must embrace continuous education models to ensure that leadership development continues beyond traditional degrees (Kangas et al., 2023; Yukl & Gardner, 2020).

Another pressing concern is the lack of formal leadership training for faculty members. Professors who lack preparation in leadership education may struggle to mentor students effectively (Bok, 2020). Faculty development programs are, therefore, necessary to train educators in leadership principles, mentoring strategies, and cross-industry collaboration (Dennis & Bocarnea, 2005; Kyllonen, 2013). Zuo et al. (2025) underscored the role of lifelong learning in fostering a growth mindset among adult learners, highlighting the value of mentorship and flexible educational frameworks in supporting this development.

Professors must be equipped not only with subject expertise but also with the skills to nurture leadership growth. Many HEIs operate leadership programs in isolation, limiting the cross-disciplinary exposure that is critical for broader leadership competencies (Bensimon et al., 1989; Rosche et al., 2023).

Leadership development must extend beyond students to include faculty, support staff, and administrators. Research shows that strong leadership at all institutional levels fosters student success, faculty engagement, and organizational innovation (Kouzes & Posner, 2019; Yukl et al., 2002). Institutions that invest systematically in leadership cultivate vibrant, adaptable academic communities (Cacioppo et al., 1996). As organizations continue to report shortages of leadership-ready graduates (DDI, 2023), HEIs must take a proactive approach. Embedding leadership development in both curricular and extracurricular activities is essential to prepare students for complex professional environments (Friesen, 2020).

In conclusion, the current research highlights the urgent need for HEIs to rethink leadership education models. Effective leadership programs must balance theory with hands-on learning, underpinned by human capital theory. Although some progress has been made, more research is needed to understand how best to structure leadership development programs aligned with a dynamic, technology-driven workforce. Building on the existing literature and the objectives of this study, the research was guided by the following research questions: 1) How do leadership directors in HEIs define and perceive lifelong learning? 2) What strategies do leadership program directors consider the most effective in fostering lifelong learning, adaptability, and leadership readiness among individuals?

Theoretical frameworkThis study is built upon three interconnected theoretical perspectives: adult learning theory, transformational leadership theory, and experiential learning theory. Collectively, these frameworks inform the design, delivery, and expected outcomes of leadership development programs in higher education, particularly concerning the lifelong learning and upskilling of the modern workforce.

Adult learning theory, particularly as articulated by Knowles’ (1984) Andragogy, or adult education (Kearsley, 2010), posits that adult learners are self-directed and goal-oriented, and bring valuable experience to the learning process. Leadership development initiatives in higher education must, therefore, align with principles that support autonomy, relevance, and practical application. By acknowledging students as emerging professionals with diverse experiential backgrounds, programs can foster more effective engagement and support long-term retention of leadership competencies (Nakash, 2025). This framework also reinforces the study’s emphasis on lifelong learning—that professional growth is continuous, adaptive, and personalized.

Transformational leadership theory (Bass & Avolio, 1994; Burns, 1978; Ellen, 2016) serves as a guiding perspective on understanding how leadership development programs are designed to shape skill acquisition as well as values, vision, and social responsibility. This theory focuses on four key components, namely, idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration, all of which feature prominently in higher education leadership curricula (Rafique et al., 2022). The integration of transformational leadership theory into this study allows for a more nuanced understanding of how institutions aim to cultivate ethical, visionary, and adaptive leaders prepared for complex challenges.

(Kolb’s, 1984, 2015) experiential learning theory provides further grounding for how leadership development programs structure learning environments. It focuses on the cyclical process of concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation. Within the context of higher education, this translates into simulations, internships, service learning, and reflective practice, representing approaches commonly embedded in leadership education. Furthermore, ELT strengthens the study’s focus on upskilling by emphasizing how hands-on learning contributes to the development of real-world competencies.

Together, these three frameworks offer a cohesive lens through which to explore the strategies and practices of leadership development programs in U.S. higher education. Adult learning theory explains the learner’s needs and motivations, transformational leadership theory defines the leadership attributes and outcomes that programs strive to foster, and experiential learning theory provides insight into how programs facilitate growth and upskilling through structured experiences. By grounding this study in these interrelated theories, this study is better positioned to interpret the findings and identify implications that are pedagogically sound, leadership-oriented, and practically relevant to higher education and workforce development.

MethodologyA basic qualitative research study design was used to carry out this study. Merriam (2009, p. 24) described a basic qualitative research study as “(1) how people interpret their experiences, (2) how they construct their worlds, and (3) what meaning they attribute to their experiences.” This study examined the lived experiences of directors of leadership programs at HEIs in the U.S., focusing on how leadership upskilling is structured in HEIs to better equip students for leadership roles in the twenty-first century and the strategies used to ensure they develop the necessary competencies for professional success.

Sampling and recruitmentPurposive and snowball sampling were used to recruit participants for this study. Purposive sampling allowed for the recruitment of participants who would best provide in-depth information about this research topic (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). The study was limited to directors of leadership programs in the disciplines of leadership studies and/or organizational leadership at a U.S. HEI. Potential participants were initially identified using the International Leadership Association database. Programs were identified using the following search criteria: (a) having a graduate leadership program, (b) being located in the U.S., and (c) offering face-to-face or blended programming. The initial list was then narrowed down to institutions that were established at least 50 years ago. These criteria are important because such HEIs have a record of accomplishment in the educational arena due to their graduate and advanced study student preparation and output, institutional longevity, and involvement in leadership research. Snowball sampling, also known as chain referral sampling, was implemented as a means to verify, prioritize, and further solicit interviewees for the study (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). Potential participants were contacted via email by the primary researcher to request their participation. The study consent form was included, which also provided additional information about the study. A reminder email was sent after two weeks to those who did not respond. Those who agreed to participate signed and returned the consent form to the primary researcher, who then scheduled the interview.

Data collection and analysisVirtual interviews were conducted as the source of data for the study in 2023. Merriam (2009) explained that interviews provide the researcher with more information about participants’ opinions, experiences, knowledge, feelings, values, behaviors, and unique perspectives. The interviews were conducted synchronously via the web-based platform, Microsoft Teams. This provided “the researcher and respondent an experience similar to face-to-face interaction insofar as they provide a mechanism for a back-and-forth exchange of questions and answers in what is almost real time” (Lune & Berg, 2017, p. 80). The choice of virtual interviewing was appropriate because participants were dispersed across the U.S.

A researcher-created semi-structured interview protocol was developed based on the literature (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016). It contained 12 open-ended questions designed to obtain specific information from those interviewed (Creswell & Creswell, 2018) and support the interviewer in exploring more about their feelings, behaviors, rich descriptions, and interpretations (Merriam, 2009). Interviews lasted approximately 45 min. The interviews were recorded using the transcription feature of Microsoft Teams, in conjunction with interviewer field notes. The transcript was checked for accuracy by the interviewer and, during this check, any identifying information was removed to maintain participant confidentiality. After the individual transcripts had been reviewed for accuracy, member checks were conducted by sending them to the respective interviewees, requesting feedback regarding accuracy and allowing them to clarify and edit any responses. The video recordings were destroyed after the accuracy checks. Data collection was terminated when no new insights emerged from the data collection and analysis; that is, data saturation was reached (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). This process resulted in 18 final participants (N = 18), and each was randomly assigned a code (D1–D18) for reporting purposes. See Table 1 for select demographic information.

Demographic Characteristics for Participating Directors of Leadership (N = 18).

Note. Totals of percentages are not 100 for every characteristic because of rounding.

The participants’ responses were structurally coded and then analyzed using comparative methods to identify emergent themes. Structural coding “applies a content-based or conceptual phrase representing a topic of inquiry to a segment of data that relates to a specific research question used to frame the interview” (Saldaña, 2009, p. 67). This initial coding serves as “a starting point to provide the researcher with analytic leads for further exploration” (Saldaña, 2009, p. 81). Within these codes, comparative methods were used to further identify themes. As it relates to comparing and contrasting, Tesch (1990) stated that it is used for all “intellectual tasks during analysis.… The goal is to discern conceptual similarities, to refine the discriminative power of categories, and to discover patterns” (p. 96). This process gives meaning to the research questions (Merriam, 2009). Four themes emerged from the analysis, which were then compared to the extant literature to draw conclusions and make recommendations.

Trustworthiness and ethical practicesRigorous qualitative research is grounded in trustworthiness. This involves credibility, transferability, confirmability, and dependability (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Credibility—a study’s internal validity measure—was upheld through researcher and participant transcript accuracy checks and a peer review (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). A peer review of the data categorization was conducted within the research team to reduce individual biases and confirm themes. The use of multiple investigators to analyze the data provided a means of triangulation from multiple perspectives and understandings of the concept at hand (Patton, 2014). Furthermore, Lune and Berg (2017) detail that triangulation provides a “more substantive picture of reality; a richer, more complete array of symbols and theoretical concepts” (p. 14).

Transferability demonstrates the applicability of the findings to different contexts. Purposive sampling allowed the selection of a specific sample to provide the most information about the research topic. This further allowed the reader to make a judgment about its transferability to another context (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Moreover, by incorporating thick descriptions of the study context and detailed descriptions of the findings, “the results become more realistic and richer” (Creswell & Creswell, 2018, p. 200). Additionally, the incorporation of direct quotes from the participants supports credibility and transferability and gives them a voice as the creators of their own stories (Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

Dependability, the ability to determine that the process of inquiry was conducted correctly, was established by creating and maintaining an audit trail. Ethical considerations must be given to participants’ well-being when interviewing in qualitative research (Seidman, 2005). Institutional Review Board approval was obtained as evidence of conforming to the professional and ethical regulations for research and to protect the human participants’ welfare.

FindingsThis study aimed to explore the role of upskilling in leadership development programs at HEIs and how such initiatives are structured to equip the next generation of leaders. The research focused on the perspectives of directors of leadership programs and investigated strategies used to enhance leadership readiness through continuous skill development. The following sections present the emergent themes derived from the data analysis.

- 1.

Lifelong learning and continuous skill development

- 2.

Strategies for upskilling the next generation of leaders

- 3.

Industry partnerships for real-world leadership exposure

- 4.

Mentorship, coaching, and certification as upskilling tools

The findings indicate that continuous skill development is essential for leadership preparation. Directors emphasized that traditional models of education are insufficient to equip students with the leadership competencies necessary for the evolving workforce. This aligns with the Introduction section’s assertion that HEIs must prioritize adaptability training and workforce readiness (World Economic Daher-Armache & Armache, 2024; World Economic Forum, 2025). Table 2 outlines the theme and representative quotes that support the analysis.

Lifelong learning and continuous skill development: Representative quotes.

Note. This list represents quotes that guided the researchers in qualitative theming. It is not an inclusive list of quotes.

Participants strongly supported the idea that leadership education must extend beyond a one-time learning experience and instead become a lifelong process. Director 1 pointed out that HEIs must reposition themselves to continuously improve, stating, “we must be better than last time.” These findings confirm that higher education must shift toward embedding adaptability training into leadership programs, aligning with the predictions that 39 % of employees’ core skills will change by 2030 (World Economic Forum, 2025).

Strategies for upskilling the next generation of leadersDirectors identified multiple strategies for upskilling students, emphasizing the importance of experiential learning, real-world application, and adaptability training. Participants highlighted that leadership programs must develop from purely theoretical coursework into comprehensive skill-building experiences. Table 3 outlines the theme and representative quotes that support the analysis.

Strategies for Upskilling the Next Generation of Leaders: Representative Quotes.

Note. This list represents quotes that guided the researchers in qualitative theming. It is not an inclusive list of quotes.

Several directors underscored the need for structured leadership training programs that integrate practical learning opportunities. Director 13 stressed the importance of fostering inclusivity and community in leadership training, ensuring that students develop leadership styles that accommodate diverse perspectives. Experiential learning emerged as a key approach to leadership development. Director 2 advocated for job-shadowing opportunities. This strategy aligns with the Introduction’s emphasis on the need for HEIs to provide structured, applied leadership training (Daher-Armache & Armache, 2024). Directors also highlighted that leadership training should extend beyond students to include faculty development. Director 6 noted that faculty leadership training is essential for institutional sustainability, adding, “People are leaving the field for the private sector because they do not feel appreciated.” Ensuring that faculty receive continuous leadership training helps create a more effective learning environment for students and reinforces the role of HEIs as leadership incubators.

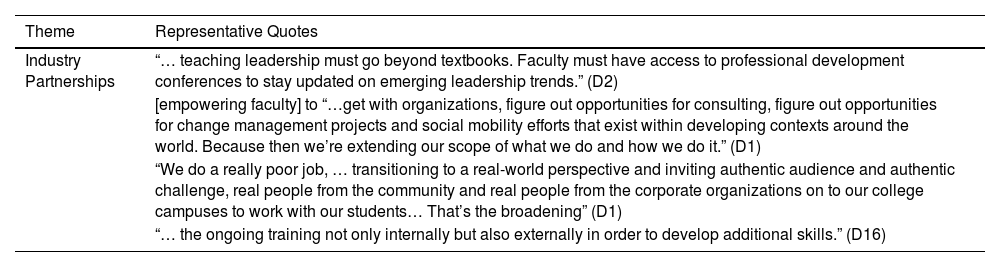

Industry partnerships for real-world leadership exposureDirectors maintained that academic training alone is insufficient and that collaborations with industry are essential for preparing students for leadership roles. HEIs must provide students with opportunities to apply their leadership skills in real-world environments, ensuring that graduates are workforce-ready. Table 4 outlines the theme and representative quotes that support the analysis.

Industry Partnerships for Real-World Leadership Exposure: Representative Quotes.

Note. This list represents quotes that guided the researchers in qualitative theming. It is not an inclusive list of quotes.

Director 1 stressed that HEIs should facilitate external consulting projects, leadership internships, and networking opportunities, allowing students to gain hands-on experience. Findings reveal that leadership programs should build relationships actively with external organizations to provide students with industry exposure. Director 12 pointed out that while student leadership programs are typically free, faculty development often requires financial investment, which limits participation. Expanding industry collaboration can help bridge the workforce readiness gap and better prepare students for leadership positions. The Introduction highlights a growing concern that without structured leadership training, HEIs risk producing graduates who lack the necessary competencies to thrive in dynamic professional environments (Bok, 2020).

Mentorship, coaching, and certification as upskilling toolsMentorship and structured certification were widely recognized as essential leadership development tools. Directors maintained that continuous professional development, beyond a traditional degree, is necessary for leadership success. Table 5 outlines the theme and representative quotes that support the analysis.

Mentorship, coaching, and certification as upskilling tools.

Note. This list represents quotes that guided the researchers in qualitative theming. It is not an inclusive list of quotes.

Mentorship emerged as a crucial component in upskilling leaders. Director 5 reinforced this perspective, highlighting the role of networking and informal mentorship in leadership development. The director explained that leadership programs should focus on “investing in students by offering networking opportunities and making sure they are at events where influential alumni are present.” This approach aligns with the finding that high-potential leaders frequently leave organizations due to a lack of career advancement opportunities (Baranchenko et al., 2020), making structured mentorship critical. Certifications and micro credentials were also identified as valuable leadership development tools. Director 9 added that micro credentials help students “stay ahead of industry trends and remain competitive in leadership roles.” These insights confirm the Introduction’s claim that HEIs must integrate structured upskilling pathways into leadership programs to better prepare students for evolving professional demands.

Overall, the findings confirm that HEIs must embed structured leadership upskilling into student and faculty development programs to ensure graduates are workforce-ready. Leadership education must prioritize adaptability, experiential learning, industry collaboration, and mentorship to equip students effectively for professional success. The study suggests several best practices, including integrating leadership training into both student and faculty development programs, fostering industry partnerships, implementing mentorship initiatives, and encouraging lifelong learning through certifications and micro credentials. By adopting a structured approach to leadership upskilling, HEIs can bridge the leadership skills gap and ensure that students develop the necessary competencies to thrive in dynamic professional environments. This study provides workable recommendations for faculty, administrators, and policymakers seeking to enhance leadership training models in higher education.

DiscussionThe findings of this study reinforce the need for continuous skill development and upskilling in leadership education, aligning with prior research that emphasizes lifelong learning as a key competency for future leaders (Daher-Armache & Armache, 2024; Li et al., 2025; World Economic Forum, 2025). This aligns with Mei et al. (2023), who underscore the importance of integrating future workforce competencies into HEI programs to meet changing leadership demands. This study highlights how HEIs must move beyond traditional, theoretical leadership training and adopt a more dynamic, skill-based approach that integrates experiential learning, adaptability training, and industry collaboration, a conclusion further supported by previous research (Li, 2024). Similarly, Lu (2023) highlights that innovation-driven, hands-on learning mechanisms are crucial to modern leadership education, supporting the call for experiential models. As leadership competencies evolve alongside technological advancements and changing workforce demands, HEIs must ensure that their programs cultivate leaders who are flexible, innovative, and prepared for real-world challenges.

Findings indicate that leadership education must extend beyond a single learning experience to become a lifelong process. This finding aligns with recent research by Zuo et al. (2025), who indicated that lifelong learning that includes formal and informal pathways is a lifetime process. Directors in this study emphasized that HEIs must prepare leaders who upskill continuously to remain relevant in a developing workforce. This aligns with previous research from the prevailing academic perspective, suggesting that effective knowledge management is crucial for sustaining competitiveness in today’s knowledge-driven environments (Dedunu et al., 2025; Sang, 2024). It further aligns with research suggesting that higher education must shift toward embedding adaptability training into leadership programs to address the 39 % change in core employee skills predicted by 2030 (World Economic Forum, 2025). Previous literature emphasizes that leadership development requires ongoing engagement in learning opportunities that focus on flexibility, critical thinking, and resilience (Kouzes & Posner, 2019). Directors emphasized that leadership is increasingly defined by the ability to navigate complexity and uncertainty rather than by technical expertise alone (e.g. Yukl & Gardner, 2020). Moreover, the directors underscored the importance of fostering adaptability, open-mindedness, and problem-solving skills, which are critical for future leaders. This finding is consistent with recent research by Zuo et al. (2025), who emphasized adaptability in an ever-changing economy.

The study further highlights the importance of experiential learning as a critical strategy for upskilling the next generation of leaders. Directors indicated that leadership programs should incorporate case-based learning, simulations, and job-shadowing to bridge the gap between theoretical knowledge and real-world application. This finding aligns with Lu (2023), who indicated that innovation-driven, hands-on learning mechanisms are crucial for modern leadership education, supporting the call for experiential models. Moreover, it aligns with research suggesting that experiential learning fosters problem-solving, decision-making, and adaptability, representing core leadership competencies required in modern workplaces (Bok, 2020). Structured leadership training programs that integrate formal and informal learning methods are essential to ensuring that students gain practical leadership experience. This finding aligns with recent research by Zuo et al. (2025), who stressed that lifelong learning includes formal and informal pathways. Previous research has demonstrated that apprenticeships and mentorship programs significantly enhance leadership capabilities (Daher-Armache & Armache, 2024; Li, 2024). Additionally, faculty leadership development was identified as a key factor in institutional sustainability. Directors noted that a lack of leadership training opportunities for faculty contributes to dissatisfaction and attrition in HEIs, aligning with research suggesting that faculty training in leadership development plays a crucial role in sustaining institutions and improving student learning outcomes (Rehbock, 2020).

Directors emphasized the importance of partnerships between HEIs and industry for real-world exposure of future leaders. This finding is consistent with Li et al. (2023), who suggested that innovation today demands collaboration among stakeholders, including partnerships between companies and HEIs. Furthermore, DDI (2023)’s study, which revealed that academic training alone is insufficient to prepare students for leadership roles, reinforcing prior research that calls for this closer collaboration. Moreover, directors underscored the importance of external consulting projects, internships, and professional networking in leadership development. They indicated that HEIs should facilitate external opportunities, extending their scope beyond traditional learning spaces to real-world contexts, which can bridge the workforce readiness gap and better prepare students for leadership positions. This finding aligns with recent research by Wang et al. (2023), who found that strong external industry collaboration is a key driver of successful digital and leadership transformation in HEIs, and McGunagle and Zizka (2020) who added that industry collaborations provide students with applied leadership experiences and prepare them for workforce demands. However, the findings highlight access barriers, particularly financial constraints that limit faculty participation in leadership training. Research suggests that HEIs should prioritize funding for faculty leadership training, as it has long-term benefits for student learning and institutional success (Daher-Armache & Armache, 2024). Expanding industry collaborations and securing external funding sources can provide additional support for both students and faculty.

Mentorship emerged as another essential component of leadership development, reinforcing previous research on the effectiveness of mentorship in professional growth (Day, 2000; Kouzes & Posner, 2019; Zuo et al., 2025). This finding is consistent with recent research by Li et al. (2023), who indicated that launching mentorship or coaching schemes strengthens the capacity and skills development of stakeholders and facilitates knowledge-sharing opportunities (Li et al., 2023). This finding also aligns with recent research by Zuo et al. (2025), who underscored the role of lifelong learning in fostering a growth mindset among adult learners, highlighting the value of mentorship and flexible educational frameworks in supporting this development. Directors pointed out that mentorship fosters career readiness, enhances leadership competencies, and increases retention rates. Networking was also identified as a key element of leadership training, and structured mentorship and networking opportunities have been shown to improve career progression and leadership development. This aligns with research by Ferreira Da Silva et al. (2023), who stress that mentorship and leadership engagement are crucial elements in agricultural graduate leadership programs, offering cross-sector applicability. Directors further noted that mentorship builds confidence in emerging leaders and helps them transition into leadership roles more effectively.

Certifications and micro credentials were identified as valuable tools for continuous leadership development. Directors stressed the importance of professional development beyond the traditional degree, emphasizing the role of continuous learning through journal articles, research, and industry engagement. This finding supports prior research showing that micro credentials help individuals remain competitive in evolving job markets by providing targeted skill development. It aligns with the research by Wang et al. (2023) who maintained that integrating flexible and continuous education models is critical for sustaining digital transformation and innovation in higher education. Directors noted that certification provides a structured approach to leadership upskilling, confirming that HEIs must integrate competency-based learning pathways into leadership programs to better prepare students for changing professional demands (Daher-Armache & Armache, 2024).

These findings highlight the urgent need for HEIs to prioritize lifelong learning, adaptability training, and experiential learning in leadership development programs. Consistent with previous research, the study confirms that HEIs must go beyond traditional theoretical education and integrate applied leadership training, industry partnerships, and structured mentorship programs to upskill students and faculty effectively (World Economic Forum, 2025; Yukl & Gardner, 2020). Moreover, recent findings by Li et al. (2024) on the challenges of digital innovation in HEIs underscore the importance of adapting educational models to foster agility, interdisciplinary skills, and leadership readiness for evolving professional environments. By enhancing leadership development initiatives, HEIs can better prepare future leaders to meet the demands of a dynamic workforce and drive meaningful contributions across industries.

Theoretical and practical implicationsThe findings of this study contribute to theoretical and practical understandings of leadership upskilling in HEIs. Theoretically, the study extends human capital theory by demonstrating how leadership upskilling serves as a strategic investment in developing individuals’ capabilities, enhancing institutional and economic outcomes, which accords with previous findings on the developing needs for innovation and human resource management in HEIs (Li et al., 2024; Papa et al., 2020). The study further supports lifelong learning theory, reinforcing the idea that leadership development is a continuous process rather than a finite educational experience. The perspectives of leadership program directors emphasize that HEIs must integrate leadership upskilling into formal academic curricula as well as through experiential learning, mentorship, and industry collaboration. This approach mirrors recent calls for competency-based education and innovation-focused training in HEIs to meet labor market demands (Mei et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2023).

From a human capital perspective, the study underscores HEIs’ critical role in equipping students with leadership competencies that enhance employability and career advancement. The findings suggest that to bridge the gap between academic leadership training and real-world application, HEIs must overcome structural challenges in digital transformation and educational innovation, as highlighted by Li, Sun, Ye and Mardani (2024). Traditional leadership education models, primarily focusing on theoretical instruction, fail to fully prepare students for the challenges of leadership in dynamic and uncertain professional environments (Li, 2024). The findings reinforce the argument that leadership training must be competency-based, incorporating adaptability, decision-making, and problem-solving skills, which employers increasingly recognize as essential (Yukl & Gardner, 2020).

In practical terms, the findings have significant implications for curriculum design, faculty development, and institutional leadership policies. First, the findings emphasize the importance of restructuring leadership programs to incorporate more hands-on learning opportunities. This is consistent with research by Mei et al. (2023), who stressed that future workforce competencies require immersive, experiential learning integrated into formal education systems. Moreover, leadership upskilling should not be confined to isolated coursework; it should be integrated into interdisciplinary programs, offering students opportunities to engage with complex leadership challenges in real-world contexts. The study highlights the need for HEIs to promote strong partnerships with industries, providing students with internships, leadership residencies, and project-based learning experiences that mirror professional leadership responsibilities. This need mirrors Lu’s (2023) findings on maker education, which is an innovation-driven, hands-on learning approach that enhances students’ training and leadership development. Without these opportunities, graduates risk entering the workforce unprepared for leadership roles that demand adaptability and innovation (Bok, 2020; Rosche et al., 2023).

Faculty development also emerges as a crucial area for institutional improvement. Many faculty members are not formally trained in leadership education, which limits their ability to mentor and guide students effectively in leadership development. The findings suggest that faculty training programs should include leadership coaching methodologies, interdisciplinary collaboration techniques, and industry engagement strategies to ensure that educators are equipped to cultivate leadership skills in students. Similarly, Li, Chen and Alrasheedi (2023) found that collaborative innovation systems in HEIs often fail due to insufficient faculty development and engagement with industry standards. Institutions that invest in faculty leadership training can enhance both student outcomes and institutional effectiveness (Rehbock, 2020). Moreover, the findings indicate that faculty should be encouraged to engage in continuous learning themselves, embracing upskilling through professional development programs, certifications, and leadership training workshops.

Another significant practical implication is the need for HEIs to create structured pathways for leadership upskilling that extend beyond degree programs. Wang et al. (2023) stressed that integrating flexible and continuous education models is critical for sustaining digital transformation and innovation in higher education. The study’s findings suggest that leadership competencies should be developed through micro credentialing, certification, and ongoing professional development initiatives. Universities that adopt flexible learning models such as online leadership training programs, leadership boot camps, and executive education courses can better support students and professionals in their continuous leadership development (World Economic Forum, 2025). Given the rapid pace of change in professional environments, leadership training should not end upon graduation but should be embedded in lifelong learning initiatives.

Institutional leadership policies must evolve to support the growing emphasis on leadership upskilling. University administrators must recognize the value of leadership education as a key component of future student success and workforce readiness. The findings suggest that HEIs should allocate funding and resources to leadership training programs, ensuring that students have access to mentorship, career coaching, and leadership networking opportunities. Similarly, Ferreira Da Silva et al. (2023) argue that leadership development in HEIs must be strategic and supported by institution-wide commitment to building future leaders. Furthermore, policies should encourage interdisciplinary collaboration among academic departments to embed leadership training across various fields of study, rather than limiting it to business or management programs. Considering the increasing complexity of leadership roles, students from diverse disciplines, including STEM, humanities, and social sciences, should be exposed to leadership development initiatives that enhance their problem-solving and strategic decision-making abilities (Friesen, 2020).

Additionally, this study highlights the importance of mentorship as a core strategy for leadership upskilling. The findings suggest that emerging leaders benefit significantly from mentorship relationships with experienced faculty, administrators, and industry professionals. Moreover, HEIs should develop formal mentorship programs that pair students with leadership practitioners, allowing for knowledge transfer, professional guidance, and real-world leadership exposure. These programs can raise students’ leadership confidence and prepare them for career progression in ways that traditional classroom instruction cannot achieve (Daher-Armache & Armache, 2024; Kouzes & Posner, 2019).

Finally, the findings underscore the broader societal implications of leadership upskilling in HEIs. As the workforce becomes increasingly knowledge-based, universities’ ability to develop adaptable, resilient leaders directly affect national and global competitiveness. Institutions that fail to prioritize leadership training risk producing graduates who are ill-equipped to lead in complex, dynamic environments. This is consistent with calls for HEIs to serve as hubs of innovation and resilience in the face of technological and societal changes (Li et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2023). By embedding leadership upskilling into higher education frameworks, HEIs can play a transformative role in shaping future leaders who are prepared to address societal challenges, drive innovation, and lead organizations effectively (DDI, 2023; World Economic Forum, 2025).

In conclusion, this study highlights the necessity for HEIs to adopt a structured, competency-driven approach to leadership upskilling. The theoretical contributions align with human capital and lifelong learning theories, reinforcing the idea that leadership development is a continuous process that requires sustained investment from universities. In practical terms, the findings emphasize the need for curriculum enhancements, faculty training, interdisciplinary leadership education, mentorship programs, and institutional policy reforms to better prepare students for leadership roles in the evolving workforce. Furthermore, as leadership demands continue to shift, HEIs must embrace innovation in leadership training to ensure that students, faculty, and institutional leaders are equipped for success in the 21st century.

Conclusion and future researchConclusionThis study highlights HEIs’ critical role in advancing leadership upskilling by embedding lifelong learning, experiential training, and interdisciplinary collaboration into leadership development programs. Drawing on the insights of leadership program directors, the findings demonstrate that traditional, theory-driven leadership education is no longer sufficient to meet the demands of a dynamic and increasingly complex workforce. Therefore, HEIs must prioritize competency-based education models that foster adaptability, critical thinking, innovation, and professional resilience. Grounded in human capital and lifelong learning theories, this study contributes to the changing understanding of leadership education as a continuous and strategic investment in future leaders. Although this study’s focus on U.S. HEIs provides valuable contextual insights, it underscores the importance of broader institutional transformations that can be adapted across diverse educational settings. By responding proactively to these challenges, HEIs can play a transformative role in preparing future leaders capable of navigating complexity, driving innovation, and contributing meaningfully to their organizations and societies.

Limitations and future lines of researchThe scope of this study centers on directors of leadership at U.S. HEIs, focusing on their perspectives on lifelong learning and leadership upskilling. Although this study follows a rigorous qualitative research design, its findings may not be entirely generalizable to other educational systems. Institutional approaches to lifelong learning vary across different regions, and the inclusion of a broader range of participants, such as faculty, students, and policymakers, could have yielded different insights. Moreover, selection bias may be present, as qualitative research relies on voluntary participation by individuals with direct expertise in the subject area (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Despite these limitations, this study contributes valuable insights into leadership development strategies within U.S. HEIs. To build on these findings, future research should expand the study scope by incorporating survey-based and quantitative methodologies, enhancing the generalizability of results. Comparative studies across multiple educational systems and international institutions could provide a more comprehensive view of lifelong learning implementation. Further exploration of the barriers to leadership upskilling and the evolving skill sets required for future leaders would add depth to the discussion. Investigating how artificial intelligence (AI) and digital learning tools can support leadership education may offer innovative solutions to current challenges. Moreover, long-term studies tracking the impact of lifelong learning initiatives on career advancement and employability would provide further evidence of their effectiveness. Future research should explore approaches to foster stronger collaboration between academia and industry, ensuring that leadership education aligns with workforce demands. Examining how emerging technologies, such as machine learning and AI, influence leadership training and decision-making processes would be beneficial. Expanding research to include community colleges and international universities would provide a more diverse perspective on leadership education. Moreover, further research is needed to explore how emerging technologies, such as AI and digital learning platforms, can enhance leadership development and to identify best practices that support global leadership readiness. Finally, analyzing best practices from institutions with well-established lifelong learning programs and assessing their adaptability to different educational contexts would offer actionable recommendations for improving leadership upskilling strategies globally.

Type of manuscriptResearch Paper.

Ethics declarationsNone.

Ethics approvalInstitutional Review Board approval was obtained as evidence of conforming to the professional and ethical regulations for research and to protect participant welfare.

Informed consentInformed consent was obtained from all individuals (Directors of Leadership) who participated in the study.

FundingNot applicable.

Competing interestsThe authors declare no competing interests.

CRediT authorship contribution statementGladys Daher-Armache: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Software, Resources, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Jalal Armache: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Resources, Formal analysis, Data curation. Hussein Nabil Ismail: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Software, Resources, Investigation, Formal analysis.