The degradation of aquatic ecosystems is one of the most pressing environmental challenges of the 21st century. Pollution, biodiversity loss, and ineffective governance all threaten the sustainability of these vital ecosystems. This study adopts a holistic approach to the study of aquatic ecosystem protection. This approach integrates citizen engagement, technological innovations, governance frameworks, and sustainable practices within the theoretical context of knowledge dynamics. The study extends Bratianu’s knowledge dynamics framework by introducing the concept of holistic evolutionary knowledge. The study thus examines the interplay between rational, emotional, and spiritual dimensions of knowledge in driving ecological stewardship. Data were collected from respondents from Romania and Greece. These two countries were chosen for their distinct ecological and socioeconomic contexts to provide a comparative perspective on citizen engagement and sustainable practices. A structured questionnaire was distributed to gather data from 374 participants. Analysis of these data was conducted using three methods. The XGBoost machine learning algorithm enabled predictive modeling. Kruskal–Wallis tests were used to assess statistically significant differences between countries. Finally, correlation analysis was performed to identify linear relationships between variables. The findings reveal citizen engagement and emotional knowledge as the strongest predictors of sustainable behavior, with multidimensional knowledge positively linked to ecological practices, thereby advancing SDG 6 and informing citizen science, policy, and environmental action.

Protecting aquatic ecosystems is a major challenge of the 21st century. In total, 80 % of global wastewater is untreated and pollutes the aquatic environment (Tariq & Mushtaq, 2023). Aquatic biodiversity is also in decline. Between 1970 and 2020, marine populations decreased by 56 %, and freshwater populations fell by 85 % (WWF, 2024). Citizen science has emerged as a way to monitor and manage water resources, collect ecological data, raise awareness, and influence policy (Walker et al., 2021). However, a holistic framework that integrates all types of knowledge in this context is lacking.

This study extends knowledge dynamics theory (Bratianu, 2016) by introducing the concept of holistic evolutionary knowledge. This concept integrates rational, emotional, and spiritual dimensions within a dynamic framework that reflects the complex relationships between people, knowledge, and the environment. By emphasizing these multidimensional interactions, holistic evolutionary knowledge provides a stronger foundation for citizen science initiatives addressing water-related goals, in alignment with the priorities of the SDG 6 Global Acceleration Framework.

Data were collected from respondents in Romania and Greece. Collecting data from two countries enabled the comparison of citizen engagement and sustainable practices in different sociocultural and ecological contexts. Romania has abundant freshwater resources, whereas Greece relies on marine ecosystems and tourism. This two-country study thus provides a unique opportunity to identify common challenges and context-specific solutions for aquatic ecosystem protection. Previous studies have shown the benefits of citizen science in water conservation (Conrad & Hilchey, 2011). However, gaps remain. For instance, there is no conceptual model integrating evolutionary knowledge in participatory frameworks, no recognition of emotional and spiritual knowledge in ecological behavior, and no comprehensive framework linking knowledge dynamics to aquatic ecosystem sustainability.

In sum, the study seeks to address the following research question: What are the key predictors of citizen engagement in aquatic ecosystem protection across different socioeconomic and ecological contexts? By integrating the knowledge dynamics framework with citizen engagement theory, this research provides a comprehensive, data-driven perspective on the factors influencing sustainable behavior oriented toward aquatic ecosystem preservation.

Literature review and theoretical backgroundCitizen engagement in environmental conservationCitizen science involves the active participation of nonexperts in scientific research. It has proven effective in fostering community involvement and generating valuable environmental data (Giardullo, 2023). According to Lupoae et al. (2025), citizen science initiatives have considerable potential to increase public awareness, empower local communities, and influence environmental policies. Citizen science initiatives such as Plastic Pirates have been effective in increasing public awareness of biodiversity loss and plastic pollution (Sinha et al., 2024). However, their impact often remains localized and short-term, with limited evidence of sustained behavioral change or integration into long-term policy frameworks.

There are notable gaps in the integration of citizen engagement with multidimensional frameworks of knowledge because the inherently subjective nature of citizen engagement means that it varies greatly depending on local conditions and the unique needs of each community (Zarei & Nik-Bakht, 2021). By actively participating in environmental practices, citizens can contribute to the health of aquatic ecosystems by providing data and fostering collective accountability (Dominguez-Rendón et al., 2024). This relationship forms the basis for the first hypothesis:

H1: Citizens who actively participate in environmental initiatives are more likely to adopt sustainable practices that contribute to measurable improvements in aquatic ecosystem health.

Through their engagement, citizens disseminate both scientific and experiential knowledge, enabling informed decision-making and behavioral change (Silva et al., 2021). Citizen engagement provides a foundation for addressing ecological challenges (Dickinson et al., 2012). However, its impact is greater when complemented by technological advancements. Such advancements can strengthen emotional knowledge by making ecological issues more tangible through real-time monitoring tools, immersive visualizations, or gamified participation platforms.

Technology and AI for ecosystem healthTechnological advancements have become a cornerstone of efforts to monitor and protect aquatic ecosystems (Bhambri & Kautish, 2024). Remote sensing, artificial intelligence (AI), and the internet of things (IoT) have transformed how environmental data are collected, analyzed, and used (Fuentes-Peñailillo et al., 2024). For example, AI-powered models can now predict water pollution patterns, thereby enabling faster and more targeted interventions (Ashoka et al., 2024). However, their accuracy depends heavily on data quality and coverage, and algorithmic biases can lead to misinterpretation of ecological risks, particularly in under-monitored regions.

In the context of citizen science, technology plays two roles. First, it enhances the accuracy and efficiency of data collection, enabling citizen scientists to contribute more effectively to environmental monitoring (Shivaraju et al., 2024). Second, access to user-friendly technological tools increase participation, particularly in underrepresented communities (Sheard et al., 2024). This impact of technology forms the basis for the following hypothesis:

H2: Accessible and user-friendly technological tools enhance the positive relationship between citizen engagement and the adoption of sustainable practices for aquatic ecosystem health.

Furthermore, the health of an aquatic ecosystem is intricately linked to the sociocultural and ecological characteristics of the local region or regions (Yose et al., 2023). Given the complexities involved, the relationship between sociocultural and ecological contexts and aquatic ecosystem health requires further exploration. Therefore, the following hypothesis is presented:

H3: Citizens’ perceptions of aquatic ecosystem health vary across sociocultural and ecological contexts, influencing the effectiveness of community- and national-level environmental governance strategies.

Technology addresses key barriers to citizen engagement. However, without supportive policies and governance structures (Miao & Nduneseokwu, 2025), its long-term ecological impact remains weak. Chien et al. (2023) reported that participatory frameworks combining technological tools with culturally relevant communication channels significantly enhance both data quality and long-term community commitment.

Governance and policy frameworks for sustainable practices in aquatic ecosystem healthEffective governance includes the creation of inclusive policies that encourage citizen participation, enforce regulations, and allocate resources efficiently (Kimutai & Aluvi, 2018). Weak enforcement mechanisms and fragmented implementation reduce policy effectiveness (Liu et al., 2018). There is still opposition to citizen-generated data, meaning that government support and laws to encourage it are required (Dominguez-Rendón et al., 2024). Governance frameworks enhance the relationship between sustainable practices and aquatic ecosystem health by reinforcing the impact of community actions (Wiek & Larson, 2012). This relationship forms the basis for the following hypothesis:

H4: Effective environmental governance at the community and national levels is associated with measurable improvements in aquatic ecosystem health.

Sustainable practices are at the heart of maintaining aquatic ecosystem health. These practices focus on long-term strategies to reduce environmental impact and restore ecological balance (Lu et al., 2015). Practices such as reducing plastic waste, conserving water, and promoting habitat restoration have had measurable benefits in improving water quality and biodiversity (Ogidi & Akpan, 2022). Citizen engagement supports these efforts by encouraging active participation in conservation practices and environmental stewardship (Sorcaru et al., 2024).

The adoption of sustainable practices by citizens not only contributes directly to the health of aquatic ecosystems but also sets a precedent for collective action (Buchan et al., 2023). By engaging in sustainable behaviors, individuals influence broader social norms, creating a ripple effect that reinforces ecological stewardship (Everard et al., 2016). Research has shown that sociocultural factors, such as education level, cultural attitudes toward the environment, and economic dependencies, such as reliance on fisheries, agriculture, or tourism, significantly influence pro-environmental behaviors and policy effectiveness (Miller et al., 2022). This dynamic relationship forms the basis for the following hypothesis:

H5: A higher level of environmental education among citizens increases the adoption of sustainable practices that improve aquatic ecosystem health.

Efforts to enhance interpersonal skills and to foster civic and public engagement require a balance of emotional, intellectual, and spiritual knowledge (Cegarra-Navarro et al., 2023). Although much of the focus has been on the rational utility of technology, its potential to engage the emotional and spiritual dimensions of knowledge remains underexplored (Fernandez‐Borsot, 2023).

Knowledge dynamics: A multidimensional framework for aquatic ecosystem healthResearch has shown that globalization drives knowledge spillovers and technological convergence. It thus accelerates the adoption of digital tools for environmental monitoring and policy implementation (Skare & Soriano, 2021). The concept of knowledge dynamics was introduced by Bratianu (2016). It emphasizes the dynamic and interconnected nature of knowledge, encompassing rational, emotional, and spiritual dimensions. The rational dimension focuses on logic and empirical evidence (Melé & Cantón, 2014). The emotional dimension centers on feelings and values (Candiotto, 2019). The spiritual dimension refers to deeper connections and moral obligations toward nature (Rechberger, 2024). In the context of environmental conservation, these dimensions together provide a comprehensive framework for understanding how knowledge evolves and influences individual and collective actions (Bratianu & Bejinaru, 2020).

Historical shifts in ecological thought illustrate the need for an integrated view. The contrasting perspectives of Darwin and Humboldt underscore an evolution in ecological thought (Montgomery, 2025). The theory of competition and resource optimization expounded by Darwin (1859)) provides a foundation for rational, data-driven analysis of the survival of species. In contrast, the holistic vision described by Humboldt (1860) sees humans as integral components of complex ecological systems. In the face of modern environmental crises, Humboldt’s vision is aligned with the holistic evolutionary knowledge perspective, which integrates scientific reasoning with lived experiences, ethical values, and empathy for all life forms.

In the context of aquatic ecosystems, knowledge dynamics can enhance both citizen engagement and the adoption of sustainable practices by fostering a holistic understanding of the interdependencies between humans and the environment (Bodin & Chen, 2023). This idea leads to the following hypothesis:

H6: The balanced integration of rational, emotional, and spiritual knowledge (knowledge dynamics) increases citizens’ engagement and adoption of sustainable practices, thereby enhancing aquatic ecosystem health.

To test the hypotheses and address the highlighted research gaps, a methodological strategy was designed. The following section details the data collection procedure, analytical tools, and techniques used to understand tailored strategies in sustainable ecosystem management.

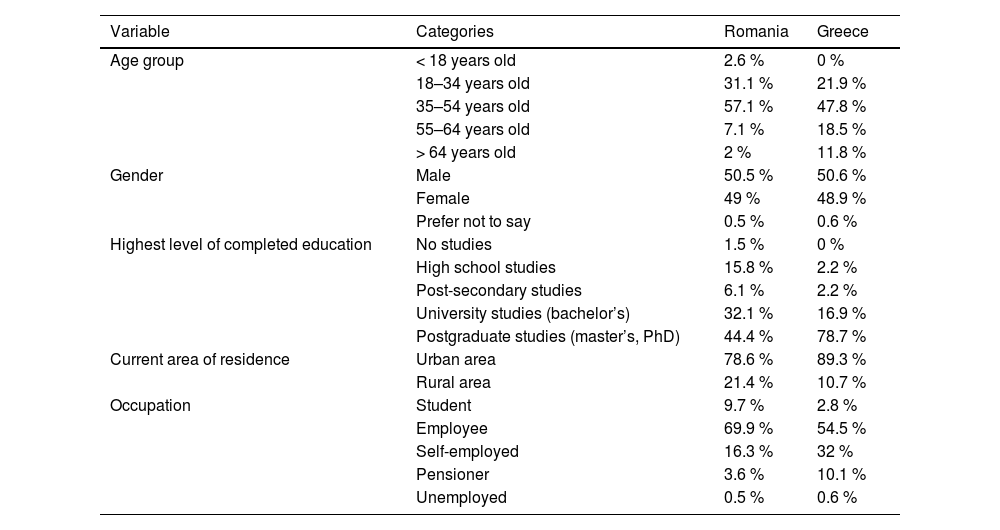

Research methodologyData collectionData for this study were collected from respondents in two countries: Romania and Greece. Gathering data from two countries provided a comparative perspective on citizen engagement, knowledge dynamics, and sustainable practices. With ecosystems such as the Danube and the Black Sea, Romania faces the challenges of agricultural runoff, inadequate wastewater treatment, and low public awareness (Kovacs & Zavadsky, 2021). In contrast, with its reliance on marine ecosystems and tourism, Greece has stronger cultural and economic ties to conservation (Gkargkavouzi et al., 2020). Meanwhile, governance in the two countries is shaped by their different sociocultural contexts (Wiener, 2007). Data were collected through an online questionnaire distributed via social media, nongovernmental organization (NGO) networks, academic institutions, and community groups. This procedure yielded 374 responses (196 for Romania and 178 for Greece) from participants involved in local environmental associations. The data collection period spanned three months and targeted individuals with varying demographic profiles to ensure a representative sample. Demographic data appear in Table 1.

Demographic data.

Notes. Data gathered from an online survey.

XGBoost is a supervised machine learning algorithm that is widely recognized for its speed and accuracy in regression, classification, and ranking (Zhang et al., 2022). As an ensemble boosting method, it combines decision trees to capture complex relationships, optimizes the loss function via second-order Taylor expansion, and uses regularization to control overfitting and handle missing values (Pan, 2018). Applications of XGBoost in water research include predicting water quality (Farzana et al., 2023; Feigl et al., 2021), modeling water scarcity (Yin et al., 2017), and analyzing inequality in access to drinking water (Oskam et al., 2021). Performance depends on the tuning of hyperparameters such as learning rate, tree depth, and subsampling ratios. Tuning is optimized using Bayesian or genetic algorithms (Barkiah & Sari, 2023). Comparative studies have shown that XGBoost often outperforms random forests and support-vector machines (SVM) when working with high-dimensional and imbalanced data (Atsauri et al., 2023). However, extensive tuning increases computational costs.

The kruskal–wallis testThe Kruskal–Wallis test is a nonparametric method for detecting significant differences between two or more independent groups when the assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance are not met (Bilan et al., 2019). If the p value is below the significance level (usually 0.05), then at least one group is significantly different. It ranks all observations, sums group ranks, and derives a chi-squared statistic to test whether groups share the same distribution. It is suitable for ordinal or nonnormal data and has been widely applied in environmental and sociological studies, including analyses of water consumption, quality, and governance (Giao et al., 2021; Heinrichs & Rojas, 2022; Kalbusch et al., 2020; Lopes et al., 2025; Olanrewaju et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2021). In this study, the Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare ordinal responses from participants from Romania and Greece. Differences in age and education reflect the real composition of the engaged populations, aligning with the study’s aim of capturing authentic cross-country variations in perceptions and sustainable practices.

Correlation analysisThe Pearson correlation coefficient measures the linear relationship between two continuous variables by calculating their covariance divided by the product of their standard deviations. The value of this coefficient ranges from –1 to +1 (Deng et al., 2021). Correlation may be considered weak (0.1–0.3), moderate (0.3–0.5), strong (0.5–0.7), or very strong (0.7–1.0) depending on the value of the coefficient (El-Hashash & Shiekh, 2022). Significance is usually set at p < 0.05 (Heu et al., 2022). Limitations include sensitivity to outliers (Armstrong, 2019), an inability to detect nonlinear relationships (Moltchanova et al., 2017), and the fact that correlation does not imply causation. The Pearson correlation coefficient has been used in environmental studies to measure public attitudes towards water conservation under stress (Gholson et al., 2019), the impact of outreach (Busse et al., 2015), community participation in conservation (Indrawati et al., 2022), and the role of trust in information sources (Eanes et al., 2017). Socioeconomic and political factors also influence engagement (Owens & Lamm, 2017). The study of behavioral science approaches such as personalized conservation programs (Moglia et al., 2018) has shown the existence of strong correlations between attitudes and actual conservation behavior.

FindingsCorrelation analysisThis study examined the correlations between six latent constructs measuring environmental perception and behavior. These constructs are described in Table 2.

Description of constructs.

Notes. Compiled by the authors.

These constructs were derived from averaged Likert-scale responses. They captured distinct dimensions of environmental engagement and awareness. Through correlation analysis, the study investigated the strength and direction of linear relationships between these constructs across two distinct sociocultural contexts: Romania (Fig. 1) and Greece (Fig. 2).

The correlation analysis showed that CitizenEngagement and SustainablePractices were most strongly linked in both countries. Respondents from Greece reported a slightly stronger practice-based connection than those from Romania. TechnologicalSupport was moderately correlated with CitizenEngagement and KnowledgeDynamics, especially among respondents from Romania. This result suggests a knowledge-oriented perspective. EcoSystemHealth perceptions were weakly related to other constructs. PolicyGovernance had weak-to-moderate associations that were stronger for the Romanian sample. Overall, the Romanian sample displayed stronger correlations among knowledge-related constructs, whereas the Greek sample displayed stronger practice-oriented links. These results reflect different cultural framings of environmental engagement. These findings, which are based entirely on self-reported perceptions and attitudes, provide insights for understanding how individuals in different cultural contexts view the relationships between various aspects of environmental engagement.

Kruskal–Wallis analysisTo investigate possible significant differences between respondents from Romania and Greece in terms of various environmental perceptions and behaviors, a Kruskal–Wallis test was conducted. The test covered 29 parameters related to water quality, ecosystem protection, citizen engagement, and sustainability practices. Statistically significant results are shown in Table 3.

Kruskal–Wallis analysis.

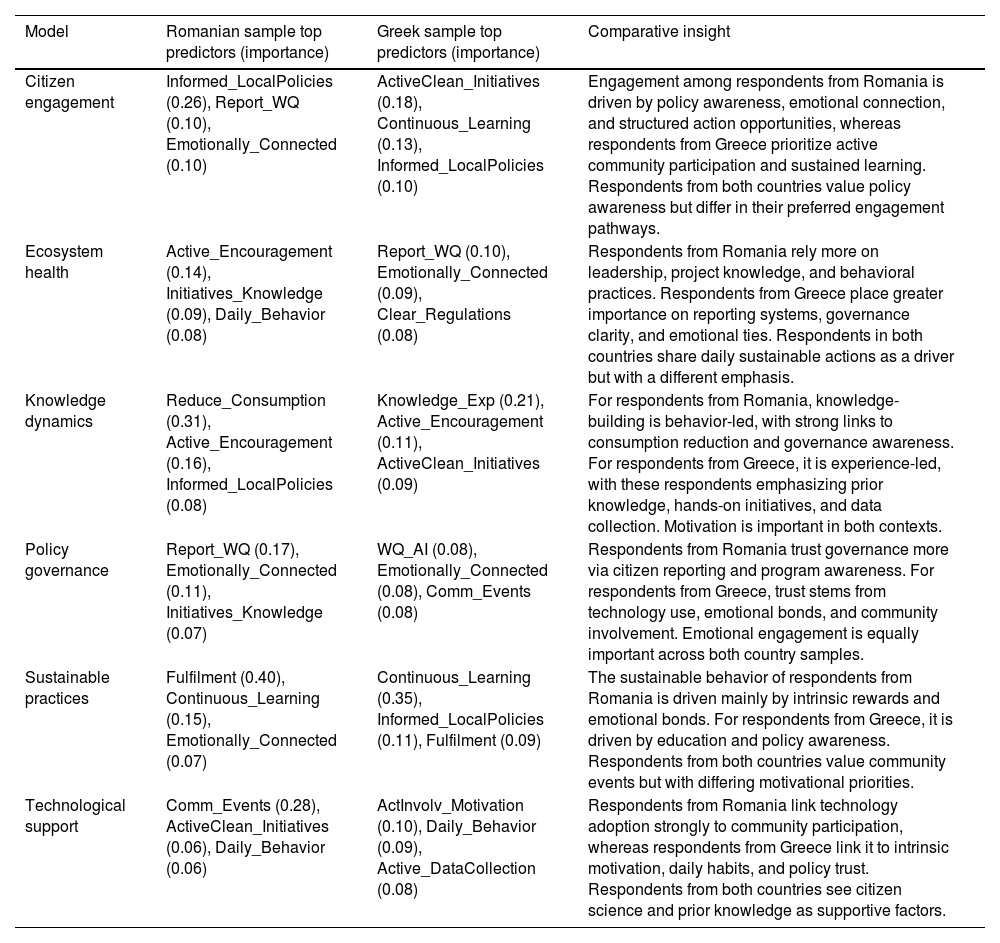

The XGBoost analysis modeled each latent variable as a dependent construct, excluding its component items to prevent data leakage. The analysis thereby identified how other factors shape public attitudes and behaviors. Separate models for the Romanian and Greek samples captured context-specific predictors. XGBoost’s ability to handle nonlinear ordinal data revealed nuanced cross-construct dynamics. Table 4 presents model performance metrics (RMSE, MAPE, R², and adjusted R²) across six latent variables: citizen engagement, ecosystem health, knowledge dynamics, policy governance, sustainable practices, and technological support.

XGBoost performance metrics.

Notes. Compiled by the authors. RMSE = root mean squared error; MAPE = mean absolute percentage error.

The performance metrics highlight cross-country differences in model accuracy. Overall, XGBoost achieved high predictive power, with most R² values above 0.90. For respondents from Greece, knowledge dynamics (R² = 0.9606) and citizen engagement (R² = 0.9579) were the strongest models, whereas ecosystem health had the weakest accuracy (R² = 0.9111). For respondents from Romania, sustainable practices were the strongest model (R² = 0.9727, RMSE = 0.11, MAPE = 2.09 %), whereas technological support had the weakest accuracy (R² = 0.9019, RMSE = 0.22). The models for the Romanian sample generally outperformed the models for the Greek sample. These differences reflect regional data patterns. The heat map in Fig. 3 visually illustrates the most influential predictors across all constructs, complementing the numerical results.

Table 5 shows details of the XGBoost results for each for each country sample. It presents the most influential predictors of Likert-scale attitudes across the six thematic models for the Romanian and Greek samples. Certain predictors, such as emotional connection, sustainable behaviors, and community participation, were consistent across both national contexts. Others were country-specific. These results thereby underscore the role of cultural, governance, and participatory dynamics in shaping attitudinal patterns.

Models and key predictors for each country sample.

The findings of this study provide strong empirical support to conclude that citizen engagement, governance, technological support, and knowledge dynamics play a role in shaping the sustainability of aquatic ecosystems. Consistent with Gautam et al. (2024), public participation was observed to be a catalyst for improved conservation outcomes, with the results of the current study revealing significant cross-country variations (H1). Ye et al. (2023) demonstrated that the success of energy efficiency hinges on active user participation. The current study confirms that citizen engagement is a decisive driver of sustainability in aquatic contexts. In Romania, engagement is rooted in grassroots activism (Nae et al., 2019), whereas, in Greece, it is primarily policy-driven (Triantafyllidou et al., 2024).

A key finding is the strong link between knowledge dynamics and citizen engagement. This finding echoes those of Rechberger (2024) and Candiotto (2019) on the role of emotional and ethical values that foster ties to nature in shaping pro-environmental behavior. While these values enhance engagement, their translation into sustained action depends on contextual enablers such as governance and technology (H2). Like the research of Haklay (2013) and Bonney et al. (2009), who emphasized the role of citizen science technologies in enhancing environmental monitoring, the current study highlights the differences in the adoption of such tools across country contexts. Dabbous et al. (2024) employed fsQCA to uncover cross-country configurations of sustainability drivers. In contrast, the current study used the XGBoost algorithm, responding to recent calls for advanced AI methods to improve predictive accuracy in citizen science and sustainability contexts (Blankesteijn et al., 2024). This approach has been shown to outperform traditional regression or structural equation modeling (SEM) by capturing complex, nonlinear relationships in data on environmental behavior. Respondents from Romania reported greater use of digital applications for citizen-driven monitoring, whereas respondents from Greece reported relying more on centralized government initiatives. These differences indicate that cultural familiarity with technology shapes adoption rates. This finding suggests the need for policy frameworks that promote accessible, community-driven technological and sustainable solutions. In this sense, recent studies have shown that gamification not only facilitates knowledge retention but also strengthens social interactions, increasing motivation for long-term environmental participation (Capatina et al., 2024).

The present findings confirm that aquatic ecosystem health is a dynamic outcome of sociocultural and ecological interactions, requiring adaptive strategies attuned to regional contexts (H3). Zhu et al. (2023) likewise noted that the sharing economy’s impact on energy efficiency primarily materializes under favorable socioeconomic and technological conditions, underscoring the importance of context-specific enablers. The comparison between the Romanian and Greek samples shows that, although certain conservation principles are universal, their operationalization demands flexibility and contextual sensitivity. This finding echoes those of Ioppolo et al. (2016) on the need for governance models that adapt to local socioeconomic and ecological realities.

Lin and Zhai (2023) reported that technology adoption in the sharing economy consistently promotes energy efficiency and pro-environmental behaviors. In contrast, the current findings indicate that, in the context of aquatic ecosystem protection, such outcomes depend strongly on governance support and sociocultural acceptance, with technology alone insufficient to drive sustained engagement. Similarly, Skare et al. (2024) showed that sustainability and sustainable competitiveness are the result of a complex interplay among digitalization, eco-innovation, financial development, and crowdfunding.

Governance played a moderate role in the model. This finding diverges from those of previous studies, which have shown stronger impacts of participatory governance models in Europe and the Global South (Bodin, 2017). In the present study, respondents from Romania valued transparency and local enforcement, whereas respondents from Greece valued public–private partnerships and incentives (H4). These contrasting perspectives highlight the need for context-sensitive governance models that balance top-down regulatory approaches. Research by Kiss et al. (2022) similarly showed that decentralized governance models foster stronger community participation, provided there is adequate policy coherence and institutional accountability. Jin et al. (2023) argued that hybrid governance models combining centralized oversight with participatory, technology-mediated systems strengthen community trust and accelerate sustainability transitions. This idea reinforces the current study’s finding that effective aquatic ecosystem protection depends on governance frameworks that integrate institutional coordination with citizen-driven technological engagement.

Education also emerged as a significant factor influencing sustainable behavior (H5). This finding supports research indicating that higher education levels are strongly associated with pro-environmental practices (Gifford & Nilsson, 2014). The current study reveals nuanced differences. Greek respondents, who had a higher percentage of postgraduate education, exhibited stronger knowledge-sharing behaviors, whereas Romanian respondents were more action-oriented in regard to local environmental initiatives. Interestingly, the correlation between perceived ecosystem health and sustainable behaviors was relatively weak. This finding supports earlier evidence (Kollmuss & Agyeman, 2002) that awareness of degradation does not automatically lead to behavioral change, particularly when economic or infrastructural barriers exist. It is also aligned with global observations that conservation action is more likely when supported by enabling conditions rather than perception alone (Brittain et al., 2025).

This study extends knowledge dynamics theory (Bratianu, 2016) by introducing the concept of holistic evolutionary knowledge, which emphasizes adaptive learning, the interdependence of ecological systems, and the dynamic interaction among rational, emotional, and spiritual dimensions of knowledge. Inspired by Humboldt’s vision (Zimmerer, 2006), it frames sustainability as an outcome that is co-created by citizen participation, institutional adaptation, and technological mediation. Aquatic ecosystem health emerges as a dynamic socioecological property, requiring regionally tailored, adaptive strategies (Ioppolo et al., 2016). The current study thus bridges the divides between cognitive science, environmental psychology, and ecological philosophy, creating a more comprehensive framework for understanding environmental knowledge transfer and sustainability adoption (H6).

In addressing its central research question, the study indicates that the most influential drivers are technological support, effective governance structures, and the interplay of rational, emotional, and spiritual knowledge dynamics. These factors operate interdependently, and their impact is shaped by the unique sociocultural and ecological features of each context. By integrating these predictors into participatory strategies, policymakers can design more adaptive and impactful approaches to sustaining aquatic ecosystems.

Practical and theoretical insightsThis study extends knowledge dynamics theory by integrating a holistic, evolutionary perspective, combining Humboldt’s approach with contemporary frameworks. It demonstrates that environmental awareness and conservation are embedded in cultural and emotional contexts, advancing the understanding of how communities internalize and act upon environmental knowledge.

Practically, the findings suggest that governance frameworks should incorporate emotional and spiritual dimensions into environmental communication, moving beyond purely rational appeals. Citizen engagement must be tailored to the sociocultural context and should be supported by capacity-building that combines technical monitoring skills with activities that foster empathy for nature. Digital tools, such as real-time monitoring platforms, immersive visualizations, and gamified citizen science, should be made accessible, culturally relevant, and emotionally engaging to maximize participation.

Limitations, future research suggestions, and conclusionsThis study advances the concept of holistic evolutionary knowledge, showing that sustainable aquatic ecosystem conservation is best promoted through the interplay of rational understanding, emotional connection, and spiritual values. Methodologically, applying the XGBoost machine learning model to predict environmental behaviors offers a novel tool for policymakers to design targeted interventions. The comparative analysis of Romanian and Greek samples underscores the need to tailor conservation strategies to the sociocultural and ecological context, showing that citizen engagement is shaped by governance structures, policy frameworks, and technological access. The study shows that AI and digital tools are key enablers, bridging knowledge gaps, enhancing transparency, and improving predictive capabilities for proactive conservation.

Despite these contributions, the study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. The study’s absence of sociodemographic controls, cross-sectional design, and restricted geographic scope invite further exploration. Although the Kruskal–Wallis test enabled valid cross-country comparison, sociodemographic differences (such as the higher proportion of older and postgraduate respondents from Greece) could act as confounding factors. Future research should adopt longitudinal approaches, broaden the chosen comparative contexts, and deepen the analysis of AI’s role in environmental governance. Nonetheless, by integrating participatory engagement, advanced analytics, and culturally attuned strategies, this research lays the groundwork for more adaptive, inclusive, and impactful pathways toward aquatic ecosystem sustainability.

CRediT authorship contribution statementDragos Sebastian CRISTEA: Supervision, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation. Oana-Daniela LUPOAE: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. Ștefan Mihai PETREA: Validation, Resources, Investigation. Ira-Adeline SIMIONOV: Visualization, Resources, Data curation. Dan MUNTEANU: Software, Methodology, Conceptualization. Catalina ITICESCU: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision.

The work was supported and co-funded from the ProCleanLakes project (ProCleanLakes.eu), which has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme, under the Grant Agreement No. 101157886. This research was also supported by The Romanian Ministry of Education and Research, grant number PNRR-III-C9-2022-I5-18, ResPonSE Project, No. 760010/2022 (specific project no.1 - Decision Support Solutions based on mathematical modeling, for complex ecological systems - CESMoSS and ResPonSE Feasibility Study).