This study investigates the determinants of restaurant managers’ behavioural intention (BI) to adopt customer relationship management (CRM)-driven service robots within the Iraqi hospitality sector. In this developing market, digital transformation remains at an early stage. Drawing on the extended Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology 3 (UTAUT3), the model incorporates performance expectancy (PE), effort expectancy (EE), social influence (SI), facilitating conditions (FC), hedonic motivation (HM), price value (PV), habit (HA), and personal innovativeness (PI). Data were collected from 283 managers employed in four-star and higher-rated Iraqi restaurants using a mixed-methods survey design and analysed using the partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) in SmartPLS v3.9. The results demonstrate that all hypothesised relationships were significant, with PI, HA, and PV emerging as the strongest predictors of adoption intention, followed by HM and PE. EE, FC, and SI exerted weaker yet meaningful effects. These findings underscore the importance of individual traits, economic considerations, and experiential motivations in shaping technology acceptance, in contrast to global studies that emphasise PE and SI. The research advances the UTAUT2 framework by integrating PI and offers theoretical insights into adoption in emerging markets. Practical implications are highlighted for vendors, managers, and policymakers in the restaurant industry who are seeking to foster service innovation under resource constraints.

In the digital age, the use of artificial intelligence (AI) has expanded beyond the IT industry into various sectors, most notably in service robots for restaurants, healthcare, and banking (Xu et al., 2025). The global hospitality industry is experiencing a technological transformation, with customer relationship management CRM)- driven service robots increasingly being deployed in restaurants to enhance operational efficiency, improve customer experiences, and address labour shortages. (Milohnić & Kapeš, 2024; Tuomi et al., 2021). These technologies possess remarkable capabilities for self-learning, communication, adaptation, and interaction with humans and other technologies. (Dang et al., 2025). The high efficiency and accuracy of AI-powered service robots, combined with machine learning, have prompted rapid adoption in the restaurant industry, as they are flexible and adaptable to changes in service delivery procedures (Kao & Huang, 2023). Service robots have become helpful in restaurants in efforts to cut down on expenses, increase productivity and profitability, and implement creative managerial ideas. The restaurant service robots perform various functions, including greeting guests, cooking, serving beverages, and accepting payments (Pancer et al., 2025). Nevertheless, the operational effectiveness of these technologies is closely linked to managerial decisions and the factors that determine their acceptance by organisations.

One of the most extensive and lively economic sectors in Iraq is the restaurant and tourism sector (Almasooudi, 2024; Belanche et al., 2020). UNESCO through Filimonau et al. (2023) It is recorded that 23,717 restaurants in Iraq were formally registered in 2018, accounting for about 65 % of the national foodservice industry. Moreover, the value of Iraq’s food imports rose from USD 10.9 billion in 2018 to USD 14.7 billion in 2023, reflecting an annual growth rate of 6.2 %, driven by expanding foodservice penetration in urban centres such as Baghdad. These figures are in line with wider regional trends - the MENA foodservice market with a 9.44 % CAGR - signalling strong growth of the sector that is likely to benefit Iraq as a segment of the regional foodservice ecosystem.

The hospitality industry in Iraq has started to undergo digital transformation and implementation of new technologies after 2021, which followed the end of the COVID-19 pandemic. It has been found recently that over 30 % of respondents in tourism and hospitality organisations claim that interaction possibilities have increased thanks to AI-based technologies (Abdul-Ridha & Al-Moussawi, 2025). This sector has also started gradually adopting the use of AI technologies, where 70 % of tourism managers in Baghdad, Najaf and Erbil expressed their full readiness to adopt modern technology and AI despite achieving actual use of this technology in the hospitality sector to about 30 % (Al-Obaidi & Jawad, 2024). Recently, the Iraqi restaurants are undergoing technological transformation, and most of the restaurants are investing in AI, with automation mechanisms to serve customers (Khan, 2024). Some restaurants, like White Fox in Mosul, have introduced service robots and interactive electronic tables, which can greet customers, deliver food and germ-free the surfaces (SNA, 2021). Similarly, RoboChef located in Karbala has used robots for food delivery and floor cleaning and also increased customer interaction with the use of interactive tables (Aljazeera, 2020). The Middle East, specifically Iraq, is an unexplored market for the adoption of service robots in the hospitality industry. However, these Iraqi restaurants also face difficulties that are related to their growth, such as limitations related to infrastructure, workforce and economy, which might affect the decisions related to using technological solutions (Chuah et al., 2021; Jiang et al., 2025).

The Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology 3 (UTAUT3) is a very detailed model that permits to discuss the technology adoption from a managerial perspective (Chaudhry et al., 2023). By making a further elaboration of the original model of UTAUT, UTAUT3 includes constructs that are particularly relevant to the organisational environment. These are: Performance Expectancy (PE)- the degree to which managers believe that CRM-driven service robots can positively impact restaurant operations; Effort Expectancy (EE)- the perceived ease of implementing and managing CRM-driven service robot systems; Social Influence (SI)- the role played by stakeholders, competitors and industry trends on adoption decisions and Facilitating Conditions (FC)- organisational and infrastructural support that is available in implementing CRM-driven service robots (Venkatesh et al., 2003). Also, UTAUT3 will include: Hedonic Motivation (HM)- the pleasure or satisfaction that managers get when using innovative technologies; Price Value (PV)- the perceived trade-off between the expenses and the benefits of investing in CRM-based service robots; and Habit (HA)- the propensity to regularly consider technological solutions when solving operational problems. (Venkatesh et al., 2012). These constructs are moderated by age, gender, and experience. In addition, Farooq et al. (2017) Extended UTAUT2 by introducing Personal Innovativeness (PI) - an individual’s psychological predisposition to embrace and adopt new ideas, technologies, and products, often independent of others’ experiences.

AI has been widely adopted in the tourism and hospitality industries due to its operational and service efficiencies and the facilitation of technology-supported functions. AI-powered service robots are now used in theme parks, restaurants, and hotels; however, restaurants have become the most prominent settings for research and practical applications (Wang & Papastathopoulos, 2023). The implementation of robotics technology has become an irreversible trend in hospitality and restaurants. A comprehensive understanding of robotics technology and how to foster human-robot relationships is essential to enhance sustainable development and advance robotics technology in the hospitality and tourism industries (Sun et al., 2024). Managers and researchers need to recognise that technological progress paves the way for new problem-solving models that address challenges faced by both customers and managers. Restaurants may adopt new solutions for various reasons, including safety considerations, particularly following the COVID-19 pandemic (Santiago et al., 2024). Future challenges await marketers, as younger generations of customers are more technologically savvy and exhibit significantly different behaviours towards AI, especially service robots, necessitating broader research on attitudes towards service robots. This research field holds promising potential across the restaurant and hospitality sectors (Abdalla, 2025).

Although there has been rapid advancement in research on service-robot adoption worldwide, a significant conceptual and contextual gap remains regarding the determinants of restaurant managers’ decisions to adopt in developing and Middle Eastern countries, especially Iraq. Several common deficiencies are evident in the literature review. First, the managerial perspective is still marginalised. For example, Milohnić and Kapeš (2024) Found managerial knowledge gaps as a key factor that hinders the implementation of robots in hotels in Croatia, and Wei and Simay (2023) and Skubis (2024) Underscored the fact that most studies have relied on executive opinions from Europe or East Asia, so developing contexts are not covered. Pande and Gupta (2022) Also noted that factors of adoption that showed support in India (may vary substantially across developing economies), emphasising the importance of manager-focused empirical research in new geographic settings. These results collectively suggest that managerial decision-making in developing markets (where organisational, cultural, and infrastructural conditions differ starkly from Western contexts) remains inadequately explored. Second, existing studies are characterised by a strong customer focus. Ghazali et al. (2025), Figueiredo et al. (2025), and Huang and Lo (2025) Focused on post-adoption experiences and consumer responses to service failures, and provided limited evidence about the strategic or operational rationale of managers in CRM-robots adoption decisions. Since managers serve as gatekeepers in translating the technology’s potential into an actual transformation of the service, this imbalance needs to be addressed. Third, the geographical concentration of extant work constrains external validity. In Marghany et al. (2025), Moliner-Tena et al. (2025), and Seo and Lee (2025) (UK, Spain, and Korea), The authors provide important insights into innovation in the hospitality industry, but warn that their results may not apply to emerging markets. Thus, expanding into the Middle East, particularly Iraq, where sociocultural norms, digital preparedness, and hospitality traditions differ, fills a clear empirical gap. Fourth, the theoretical scope of the existing models needs to be broadened. Though TAM and UTAUT/UTAUT2 have been the most used frameworks (Han et al., 2024; Kao & Huang, 2023; Rosman et al., 2023). The UTAUT3 framework, which incorporates HM, PV, HA, and PI, has not yet been confirmed in the hospitality or restaurant management context in developing economies. Therefore, testing UTAUT3 among Iraqi restaurant managers provides new theoretical validation and contextualisation. This research problem leads to the following central question: To what extent do PE, EE, SI, FC, HM, PV, HA, and PI shape Iraqi restaurant managers’ intentions to adopt service robots within a CRM-driven context?

The current study aims to understand and explore managers’ perspectives on the adoption of CRM-driven service robots in Iraqi restaurants, using the UTAUT3 framework and its constructs: PE, EE, SI, PV, HM, HA, and PI. This research is anticipated to make several important contributions: the validation and potential extension of UTAUT3 within a new cultural setting, thereby offering insights into cross-cultural patterns of technology adoption; the first comprehensive investigation of service robot adoption from the perspective of Iraqi restaurant managers, addressing a significant geographical and contextual gap in the literature; the development of culturally appropriate measurement instruments and methodological approaches for technology adoption studies in Middle Eastern contexts; and the provision of actionable recommendations for stakeholders engaged in the implementation of service robots within the Iraqi restaurant industry. This paper is divided into seven parts: introduction section, theoretical background, methodology, result, discussion, theoretical and practical implications, and lastly, conclusions and future research.

Literature reviewCRM-driven service robots in restaurantsThe unprecedented technological advancements experienced in recent times has caused an extraordinary change across sectors, notably robotics, and fundamentally transforming human interactions and influencing the future (van Doorn et al., 2025). Robots, as programmed entities which can perform many different tasks at the same time, are predicted to displace some 75 million jobs while creating 133 million new ones by 2025 (Mukherjee et al., 2021). Initially developed to perform repetitive, monotonous tasks with a remarkable speed and precision, robots are now being asked to replace human beings even in the analytical and emotional fields, thanks to the mixture of AI and sensor technologies (Leung, 2022). The substitution of human labour with robotics is still accelerating, with more than 100,000 robots now working in Amazon’s warehouses all over the world preparing packages to be delivered (Belanche et al., 2020). Major corporations such as Lowe’s have substituted the "LoweBot" to assist customers within stores instead of having human employees. In contrast, robots like Nao assist clients in opening bank accounts at banks like Tokyo Bank (Sabir et al., 2023). A robot can be conceptualised as an artificially intelligent and programmable machine created to do a variety of tasks in a variety of environments (Mohammed, 2021; Shymaa, 2021). These include intelligent systems, like software applications, chatbots, virtual assistants and self-driving cars (Begum et al., 2025). The service sector increasingly uses innovative technologies to improve customer service with many organisations using robots to cater to customer needs better (Bartoli et al., 2025). The boom in service robots is attributed to their falling costs, changes in service demand, a move towards sustainable operations, and to prevent the spread of infectious diseases (Cabrilo et al., 2024).

Customer service robots have revolutionised the way organisations communicate with their customers and have particularly excelled in the tourism, hospital, financial and healthcare industries (Du et al., 2024). By handling large volumes of information at high speed, AI is better than humans at meeting customer needs, a phenomenon enabled by robotics (Frank & Otterbring, 2023). Service robots constitute a sub-domain of AI in the form of interactive, socially engaging physical objects that can move, communicate, and deliver services independently or semi-autonomously (Begum et al., 2025). Their form makes them sociable and forms a shared value with human beings through their functional and social purposes (Pitardi et al., 2021). Service robots make interaction and service provision easier and more efficient, enabling managers to focus on other services, such as customer relationship management (Ferhataj et al., 2025). These robots are part of overarching service systems and use cameras, audio sensors, and detection technologies to tap into the information stored in various sources, including organisational knowledge bases and CRM systems, so that they can use the records of customers, their preferences, and transactional data to draw on the history of customers (Wirtz, 2020).

The recent literature has put emphasis on the diversity of applications of service robots in the restaurant industry and their capacity to enhance customer interaction and provide pleasant experiences (Zhao et al., 2025). The defining feature that makes CRM-driven robots different from other technologies is their ability to interact with customers in an automatic manner. It is, however, different in how it integrates such autonomous service tools into the hospitality industry, especially in restaurants, where personal interactions have always been considered critical (Chuah & Soeiro, 2025). Such robots can be used in the hospitality industry to meet visitors, cook meals, handle reservations, and act as a new labour force providing 24/7 service (Becker et al., 2022). AI-powered robotics have been adopted within the restaurant industry for their efficiency and accuracy in operations as well as their capability to adjust to new methods for service delivery (Söderlund, 2023). A great leap in intelligence has also been achieved in smart restaurants without workers that can provide hard services (Gupta et al., 2024). In such environments, robots enabled by CRM will deal with guest cheque-ins and service requests with minimal human intervention as in the case of human-free restaurants operated by Marriott International (Madhan et al., 2023). The main challenge for restaurants is to deliver the personalised customer experience and every guest must be connected with the restaurant. In this case, CRM-based robots are important for personalising services such as food ordering, ordering additional services, taxi booking, and reading messages (Huo et al., 2025). Chatbots can access customer information and make personalised suggestions based on past activity (El-Said & Al Hajri, 2022).

CRM-based robots are a new form of AI in the hospitality industry that utilise the Internet of Things (IoT) to facilitate numerous functions, such as controlling room lights, managing reservation systems, or facilitating guest check-in Santiago et al. (2024). These robots make the operation more efficient, cost-effective to labour, offer immediate service and experience to users who prioritise speed and convenience, and, simultaneously, improve worker satisfaction (Lu et al., 2024). Restaurants have begun deploying and using them which reduces costs, increases efficiency, and improves the customer experience. But there are also robots such as BellaBot, which are used for cooking, flipping burgers, preparing salads, baking pizza, or making coffee, which reduce human contact with food and therefore reduce the transmission of diseases (El-Said & Al Hajri, 2022). Robots such as the Servi waiter robot also decrease the workload of employees by automating the process of order taking and service interaction (Peng et al., 2024). Service robots are also used in restaurants to perform crucial tasks like table cleaning, bulk sanitisation of dishes, floor cleaning, etc., which help in reducing operational costs significantly (Qian & Wan, 2024). Most notably, they’re being used for food deliveries to tables and more and more in home deliveries, as Domino’s Pizza has been doing in Texas with robocars (Zibarzani et al., 2024). Examples of robotic applications in restaurants: Botlr robot server at Starwood Hotels, food delivery robots of Pudu Robotics, robotic chefs with human like arms and Theresa robot server on Chinese restaurants (Byrd et al., 2024), fully physical VECTOR robot for interaction and service delivery, Pepper robot to welcome guests and introduce the offerings of the restaurant (Pancer et al., 2025).

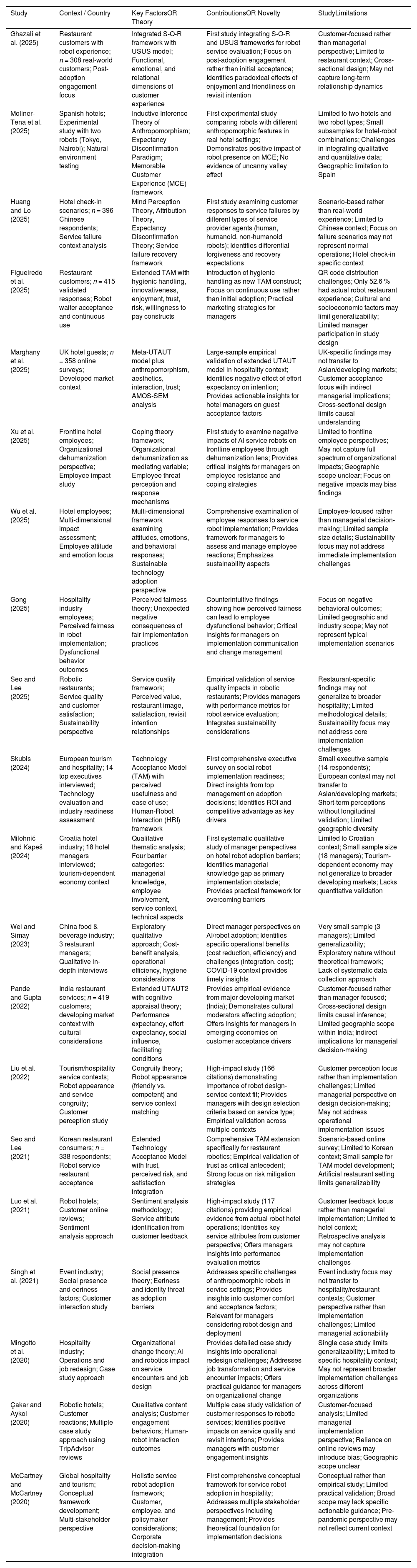

The UTAUT3 perspective and hypotheses developmentAs shown in the Appendix 1Table A1, the literature review shows that there has been a notable development in service robot adoption research, whereby stakeholder perspectives are taking a more comprehensive approach to the subject area. The findings indicate that the implementation process needs to pay particular attention to technology acceptance factors beyond the traditional ones. For managers of Asian and developing markets, the new evidence suggests the need for extensive pre-implementation planning that covers these issues. The literature reflects a progression from simplicity studies of technology acceptance to complexity, multi-stakeholder, models that are reflective of organisational robot deployment. However, there are still major gaps in the validation of new models of acceptance of new technologies and on the empirical research for managers, which suggests the need for research that contributes directly to managerial practise for a wide range of market contexts, especially developing countries.

One of the most significant factors affecting organisational development throughout the recent decades is the ability of organisations to adapt and implement technological advancements. Researchers have presented a number of theoretical frameworks to analyse the integration of technological evolution and its application in the context of organisations, among them, the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and the UTAUT are prominent (Antonio et al., 2025). The progressive history of the UTAUT3 should be viewed as the extrapolation of decades of technology acceptance research. The journey starts with the TAM which identified the process of perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use as key predictors of technology adoption and framed these as parsimonious cognitive beliefs that have validated scales that have consistently explained the intention and usage of technologies across contexts (Davis, 1989). Nevertheless, with the passage of time, research developments resulted to better knowledge of the shortcomings of TAM which focused only on individual cognition, which lead to the development of UTAUT (Van Schaik, 2009). The original UTAUT, advanced by Venkatesh et al. (2003), was a synthesis of eight previous models of acceptance used to explain technology adoption based on four core constructs: PE, EE, SI, and FC, and it exhibited high predictive validity. Venkatesh et al. (2012) introduced UTAUT2, which adds three new constructs (HM, PV, and HA) to the framework to extend the study to consumer settings. Thereafter, UTAUT2 was also referred to as UTAUT3, particularly in educational technology research. These models often integrated constructs such as trust, PI, usability, or contextual factors relevant to e‑learning and AI tools (Or, 2025). Formally, Farooq et al. (2017) as a first scholar, proposed a UTAUT3 variant by explicitly adding PI in IT to the existing UTAUT2 constructs - resulting in a model with eight predictors (PE, EE, SI, FC, HM, PV, HA, and PI) - and reported that it explained approximately 66 % of variance in acceptance and use.

As presented in Appendix 1, Table A2, the literature finds solid support in the literature for the application of the TAM in relation to the service robot adoption in the hospitality sector and the evidence supporting the relevance of perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and perceived trust. However, UTAUT / UTAUT2 / UTAUT3 applications, survey studies, and behavioural validation are still in big gaps. Future research should focus on these areas while increasing the sample size of managers and increasing the rigour of the methodology. In conclusion, it is evident from matrix that despite the foundation laid, there is a need for a deeper theoretical application as well as methodological sophistication if we are to understand the intricate dynamics of service robot adoption in the hospitality domain, in this case, restaurants.

The major reason for choosing UTAUT3 is that it has a greater explanatory power because it incorporates these predictors. This renders it much broader than TAM, UTAUT or UTAUT2 that either limit the scope of adoption determinants to a small range of utilitarian beliefs or neglect the psychological and relational dimensions that are important when it comes to acceptance of autonomous technologies (Venkatesh et al., 2012). In the case of service robots, where the adoption decision (especially by managers) depends not only on performance results but also on other perceptions, simpler models are not enough. The pros and cons of relying on the PI construct The empirical evidence has been consistently positive in demonstrating that the incorporation of the PI construct greatly improves the predictive power of the model for emerging technologies (Farooq et al., 2017; García-Sánchez et al., 2020). By overcoming these limitations, UTAUT3 offers a holistic and context-sensitive framework, especially suited to measuring managers’ adoption of CRM-driven service robots, that considers not only utilitarian and hedonic factors but also the important PI dimension that governs managerial decision-making in organisational adoption. While UTAUT and UTAUT2 have been used widely in AI-based organisational systems (Doven et al., 2025; Jain et al., 2022; Nguyen et al., 2022; Shah et al., 2024), the application of UTAUT3 in a range of contexts, such as restaurant service robots, hotel robots, and collaborative robots, is an emerging research opportunity. The theory gives a strong theoretical basis on which to investigate the major drivers behind the adoption of AI tools and robotics in organisations. UTAUT3 brings together a number of models to investigate how human actors and robots dynamically interact in organisational settings (Engesser et al., 2023). In particular, the UTAUT3 framework covers eight key constructs that are related to the adoption and usage of emerging technologies, such as CRM-driven service robots:

Performance expectancyPerformance Expectancy (PE) is the user's perception that technology will enhance his or her performance of the job. It summarises the person's perception about the utility of a given technology (Della Corte et al., 2023). Specifically it is the belief that by using a given technology will directly lead to a better performance in one's task. The magic of better performance is a major incentive to develop user demand for new technologies (Bellet & Banet, 2023). In the context of robotics in the organisational setting, PE is about the user's perception of the robot's capacity to improve work outcomes and focuses on attributes such as accuracy, consistency and reliability (Antonio et al., 2025). It is the degree of the faith that people possess in utilising the technological systems to perform better in their work (Abdalla, 2025). Within the restaurant sector, the performance that robotics is expected to perform in dealing with customer relationships play a large role in influencing managers' BI to adopt such technologies (Bhatnagr & Rajesh, 2023). The physical benefits of robotics in the restaurant industry - including greater efficiency, improved ability to be creative in the delivery of service, and higher guest satisfaction - underscore this expectation (Carretta et al., 2024). Service quality is a basic feature in the hospitality industry. Restaurant management knows how effective robots are at tasks in the day-to-day running of the business, thus freeing up the human employees to focus on more complex customer interactions (Ngusie et al., 2024). PE in restaurant robotics are also associated with market segmentation and the identification of customer preferences and requirements. Through advanced analyses and predictive capabilities in CRM systems, robots can customise their responses to align with customer expectations Aideed et al. (2025). Furthermore, the perceived performance of robotics in restaurants is strongly linked to trust. Restaurant managers know that robots can build positive relationships with their customers, creating a performance advantage that drives customer loyalty and satisfaction (Oltra et al., 2025). Gajić et al. (2024) show that managers consider service robots based on their expected operational value, such as efficiency gains, lower labour costs, and improved service speed, while Lin et al. (2025) showed that managers consider functional value and expected ROI when deciding to adopt robots for continuous operational use. Considering the above, we suggest the following:

H1 PE has a positive impact on the BI of Iraqi restaurant managers’ adoption of CRM-driven service robots.

Effort Expectancy (EE) refers to the user’s belief that technology will enhance their work performance and their perception of how easy it is to use the technology. (Engesser et al., 2023). It is the effort expected to understand and use the technology and is indicative of the user’s perception of ease of use. In other words, it assesses whether the technology is user-friendly, reduces cognitive load, and simplifies complex tasks. The more capable the technology is in these aspects, the more likely it is to be adopted (Lin et al., 2025). EE captures the degree of effort an individual perceives is necessary to use the system, or the extent to which it requires minimal effort (Gupta et al., 2022). In the restaurant sector, managers are inclined to adopt CRM-driven robots when they perceive these robots as easy to use and requiring minimal effort to learn and operate. The expectation is for these robots to streamline and efficiently perform the tasks such as cooking, sanitising and delivery, thus enhancing work performance due to ease of use and user-friendly interfaces (Bhatnagr & Rajesh, 2023). Restaurant managers expect that CRM-driven robots will help automate the routine activities like sanitisation and delivery, which will make the job less cumbersome for employees and they can focus on higher value activities. This automation is viewed as a way to improve work performance by improving efficiency and reducing errors (Deshmukh & Mehta, 2024). Ding et al. (2023) Demonstrate that managers takes into consideration some complexities in implementation, technical interoperability and operational overhead considerations when assessing service robots and research from Aliyu and Beyioku (2025) Reveal perceived ease of integration and maintenance requirements appear to have a significant implication on managerial adoption decisions. In light of the aforementioned, we propose the following:

H2 EE has a positive impact on the BI of Iraqi restaurant managers’ adoption of CRM-driven service robots.

Social influence (SI) refers to the extent to which an individual perceives that their social environment supports or necessitates the adoption of technology. It serves as a key motivator for initial intentions to adopt technology, driven by external pressures such as peer or supervisor influence (Della Corte et al., 2023). SI is the perceived value or acceptance of technology use in an individual’s social network. This includes the perception that family, colleagues or other influential people support the use of technology (Lin et al., 2025). It can also be viewed as the pressure by others on an individual to make an organisation in a new technology or system. This view is affected by a person's social network, these are family members, their friends, their peers, and this influences their inclination to adopt AI tools (Aideed et al., 2025). Managers are likely influenced by the attitudes of their colleagues to new technologies. When peers demonstrate a positive approach towards CRM-driven robots, this will help to create an environment for others to adopt similar technologies in a positive manner. Peer influence is therefore a critical factor in the promotion of collective acceptance of technology in the workplace (Tiwari et al., 2021). This SI happens through many channels, including social norms, trust for technology, and an organisational culture that promotes creativity and encourages technology adoption. Collectively, these factors make the integration of CRM-driven robots into customer relationship management in the workplace (Carretta et al., 2024). Kervenoael et al. (2020) Show managers consider customer perceptions, stakeholder expectations, industry trends as social pressures which affect adoption decisions, and Ivkov et al. (2020) Research revealed that managerial decision was guided by competitive positioning and guest experience expectations in hospitality environments. Taking into consideration the above we suggest the following:

H3 SI has a positive impact on the BI of Iraqi restaurant managers’ adoption of CRM-driven service robots.

Facilitating conditions (FC) are defined as the user’s perception that support or services are available to assist the user in adopting a technology, including infrastructure and technical support, and they affect the user’s intention to use it. It captures the extent to which the individual feels there is organisational support including the availability of organisational and technical infrastructure that makes it easy to use the systems (Wu et al., 2025). FC is a measure of the perception of available resources needed for promoting the adoption and use of technology. Such conditions reflect the extent to which organisational and technical resources (e.g. tools, technical support, training and infrastructure) are available to enable the practical use of the system (Taneja & Bharti, 2021). In the restaurant sector, FC has a strong influence on managers’ willingness to adopt AI-driven service robots through the environment and tools it provides to support efficient adoption. FC presupposes the availability of resources such as training programmes, essential equipment, and technical support (Engesser et al., 2023). Technological infrastructure, such as software systems, internet connectivity, and maintenance, is crucial for ensuring the smooth integration of service robots into restaurant operations and thus augmenting managerial capability to adopt CRM-driven service robots (Deshmukh & Mehta, 2024). When managers feel their organisation supports technological efforts through incentives for adopting new technologies and have a positive attitude towards it, they will tend to develop a favourable attitude towards the adoption of CRM-driven robots (Oltra et al., 2025). Ding et al. (2023) show that managers explicitly mention availability of technical solutions, training capacity, maintenance support, and organisational readiness as critical FC. In contrast, Gajić et al. (2024) demonstrate that inadequate change management resources and "Wild West" implementation approaches create barriers to successful adoption. Building on the above literature, we hypothesize the following:

H4 FC has a positive impact on the BI of Iraqi restaurant managers’ adoption of CRM-driven service robots.

Price value (PV) is the correlation between the financial cost of a technology and the perceived value of its use. It encapsulates the degree to which technology is reasonably priced and affordable, which, in turn, affects its adoption (Bellet & Banet, 2023). PV is an important factor in a user’s choice to accept or reject a technology. When managers perceive the benefits outweigh the expected costs, they tend to persist with the use and adoption of the technology. On the other hand, if costs of an innovation are perceived to be greater than the expected benefits, the adoption will be discouraged. PV includes not only financial costs of devices and equipment, but network associated costs, as well as non-monetary costs such as the potential effort and time required (Khanfar et al., 2024). PV is an important predictor of user behaviour, which influences BI restaurant managers to use CRM-driven service robots. It is a complex problem that includes the understanding of the perceived benefits of the technology (Hu et al., 2025). The perceived value and benefit of the CRM-based service robots is a significant factor in deciding the intention of managers to implement these technologies. When managers perceive that technology makes their task performance better and also the service offered to their customers, they will be more likely to believe that it is applicable, thus increasing their willingness to adopt service robots in restaurants (Menon & Shilpa, 2023). The implementation of CRM-driven service robots is a cost benefit analysis by managers. Notwithstanding, if the perceived benefits, such as the decrease in workload and improved quality of service, are more extensive than the costs connected with the technology, managers are more probable to be supportive of, and adopt, these technologies (Graham et al., 2025). Aliyu and Beyioku (2025) found that cash flow, return on investment, and cost-benefit analyses are key economic factors that directly impact managerial adoption, whereas Lin et al. (2025) found that initial setup costs, ongoing maintenance costs, and uncertain life-cycle costs significantly affect managerial adoption intention. With the above in mind, we offer the following:

H5 PV has a positive impact on the BI of Iraqi restaurant managers’ adoption of CRM-driven service robots.

Hedonic motivation (HM), it is grounded in the pleasure derived from using technology. It is a key element of a user’s intention to use new technologies: the degree to which their use is perceived as enjoyable, for example, in the case of electronic games and mobile applications. (Tiwari et al., 2021). HM is a key factor in the acceptance of technology - the extent of fun and enjoyment gained from its application. It emphasises the emotional aspect of technology use, suggesting that technology is not only functional but also fun (Gupta et al., 2022). HM captures the manager’s pleasure derived from interacting with technology, where the adoption is coupled with excitement and satisfaction, beyond the functional benefits (Taneja & Bharti, 2021). The hedonic value of utilising technology positively influences the BI’s decision to adopt it. Managers are more likely to embrace CRM-driven service robots if they see these systems as fun and engaging, offering an immersive, pleasant experience that significantly impacts their willingness to adopt the technology in their restaurants (Proulx et al., 2023). Kervenoael et al. (2020) Argues that managers take into consideration guest enjoyment, novelty value, and marketing benefits as hedonic aspects of service robot adoption, whereas Lin et al. (2025) Found that managers are differentiating between trial adoption (where novelty is important) and operational use in their decision-making processes. Based on the preceding, we put forward the following:

H6 HM has a positive impact on the BI of Iraqi restaurant managers’ adoption of CRM-driven service robots.

Habit (HA) is a person’s routine or instinctive behaviour, informed by previous exposure to products or technology. HA pushes people towards certain behaviours and can prevent them from changing. It is expected that HAs affect the users’ intentions to adopt technology (Wu et al., 2025). HA reflects the user’s tendency to engage in behaviour related to technology use based on their prior learning and experience; i.e., technology becomes part of individuals’ habits and is used across their daily activities (Abdalla, 2025). As people share their experiences with others, the widespread use of technology is accelerated, easing the transfer of technology and problem-solving (Bellet & Banet, 2023). The repetitive nature of tasks and the familiarity that can be attained through the use of technology over time encourage managers to use CRM-driven service robots in their daily operations (Proulx et al., 2023). HA, as a psychological construct, plays an important role in shaping restaurant managers’ BI towards the adoption of new technologies, such as CRM-driven service robots (Graham et al., 2025). HA has a positive impact on BI by shaping managers’ attitudes towards service robots, driven by past experiences and interactions with technology. Managers who are accustomed to technology tend to view new technologies as user-friendly and beneficial (Menon & Shilpa, 2023). Gajić et al. (2024) and Ivkov et al. (2020) suggest that managers with prior technology implementation experience and established innovation practices demonstrate different patterns of technology adoption, and Ding et al. (2023) suggest that organisational HA related to technology adoption and change management shapes the managerial decision-making process. With consideration of the above, we recommend the following:

H7 HA has a positive impact on the BI of Iraqi restaurant managers’ adoption of CRM-driven service robots.

Personal innovativeness (PI) is a trait that urges some people to use new technologies (Farooq et al., 2017). It reflects the capability of an individual to interact with the technology to be adopted (Khanfar et al., 2024). PI is the ability of an individual to do things using devices and technologies, including communicating with devices that use AI (Gupta et al., 2024). It is the propensity of people to accept new technologies, to utilise them, to adapt to its developments, to adopt and spread them (Hu et al., 2025). The level of PI of managers for intention to adopt technology has a positive effect. Such managers are more likely to embrace new technologies, for example, CRM-based service robots (Lai et al., 2024). Those with PI have much less resistance to change which is important in the adoption of new technologies such as robotics in organisations. Such managers show greater acceptance of CRM-driven service robots in restaurants and a stronger ability to adapt to and implement these technologies (Ngusie et al., 2024). Gajić et al. (2024) Showed that managers consider the strategic fit with company vision and mission as an innovation driver for service robots, and that. Kervenoael et al. (2020) Identified collaborative capabilities and technological development of the robot as factors for competitive positioning and adoption decision-making. In light of the above, we suggest the following:

H8 PI has a positive impact on the BI of Iraqi restaurant managers’ adoption of CRM-driven service robots.

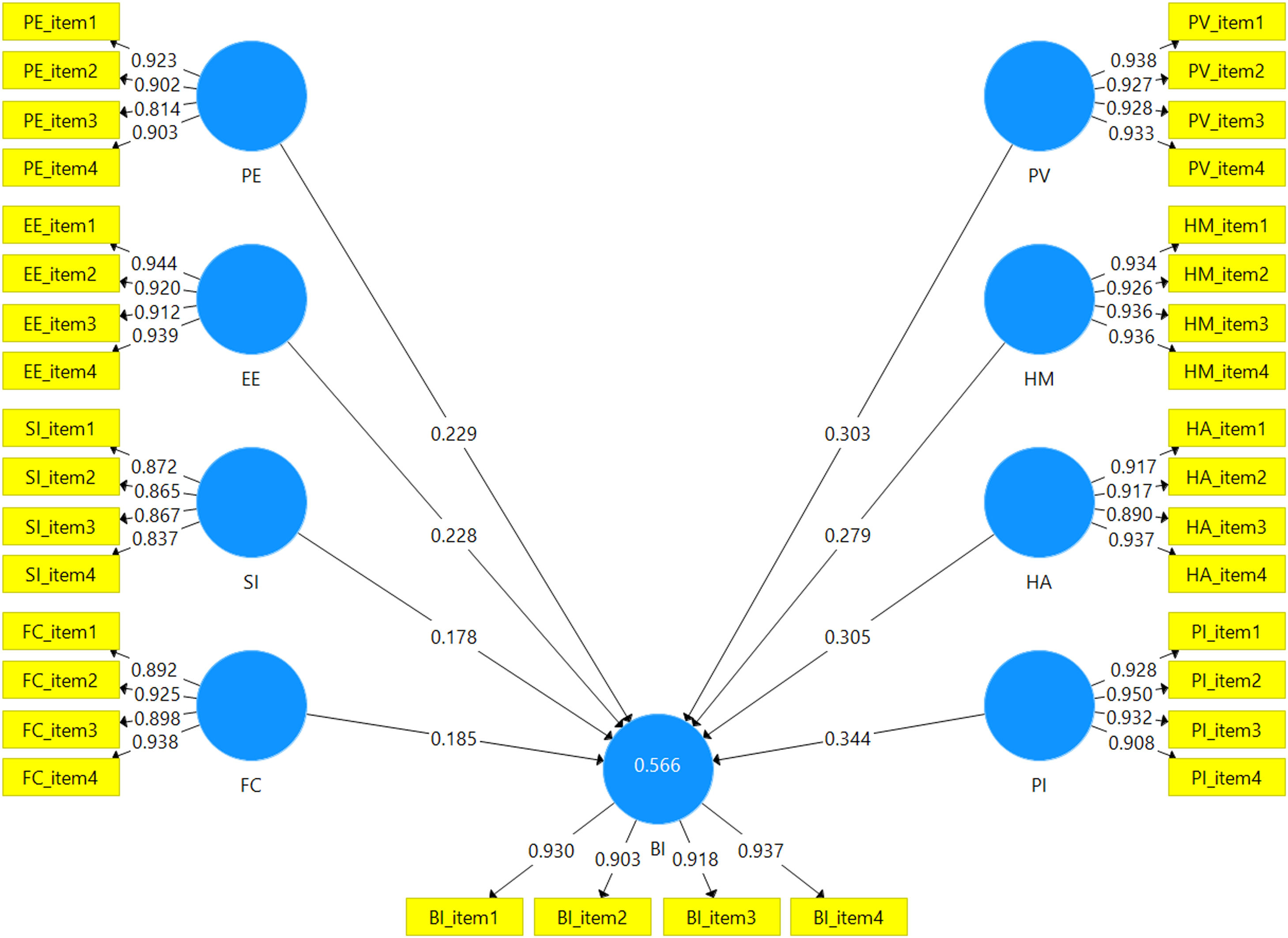

This study focuses on BI in the context of the adoption of CRM-driven service robots in restaurants, based on UTAUT3 (see Fig. 1). Accounts of current or planned advanced technology use are presented through the views of restaurant managers who are currently implementing or plan to implement new technologies in the foreseeable future. The focus is specifically on the Iraqi restaurant sector, more specifically on establishments rated four stars and above, as these are more proactive in continuously incorporating robot services and making greater use of automation than other restaurants. The moderating variables, such as gender, age, and experience, as suggested by Venkatesh et al. (2003) They were excluded from the current study to reduce its complexity.

To evaluate our research model, we used partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) with SmartPLS v.3.9. PLS-SEM is ideal for this study because it supports exploratory research with complex models and works well with small or non-normally distributed samples (Churi et al., 2021; Hair et al., 2022). It accommodates both formative and reflective constructs and is widely used in technology adoption research, like UTAUT3 (Abdulmuhsin, Owain et al., 2025; Farooq et al., 2017; Salifu et al., 2025). This makes it suitable for predicting the adoption of CRM-driven service robots in emerging contexts such as Iraqi restaurants.

Variables measurementThe questionnaire consisted of two sections. The first section included a series of preliminary screening questions (i.e., respondents’ willingness to participate voluntarily in the survey, as well as their prior knowledge about robots used in restaurants) and demographic characteristics of the respondents (i.e., gender, age, education, and experience). The second section contained questions (measured on a five-point Likert scale) related to the study variables, based on previously established scales from relevant studies on UTAUT, UTAUT2, and UTAUT3, preferred for their demonstrated reliability and validity. To measure the study’s variables, we adapted the scales used by Agarwal and Prasad (1998), (Dodds et al., 1991), Farooq et al. (2017), Gupta and Priyanka (2025), Venkatesh et al. (2003), Venkatesh et al. (2003), Venkatesh et al. (2012), Wu et al. (2025), and Zeithaml (1988). The questions were adapted to the context of this study for measuring acceptance behaviour towards the CRM-driven service robot in the restaurant sector. After making a pool of relevant items from the literature review, a total of 36 items were selected, which are presented in Appendix 2.

Data collection and sampleThe authors obtained an updated list of five- and four-star Iraqi restaurants, including their names and contact information (cell phone numbers and/or email addresses), from the Food Safety Department of the Iraqi Ministry of Health. These establishments accounted for 1.1 % of all five-star restaurants and 4.6 % of all four-star restaurants among the 24,000 restaurants registered in Iraq in 2024. To achieve comprehensive representation across different groups, a systematic random sampling approach was used; every fourth restaurant on the list was contacted via WhatsApp or email between March and July 2024. In total, 342 restaurants were contacted, and 283 managers completed the survey (either on paper or electronically), yielding a final response rate of 82.75 %. According to Hair et al. (2010), a minimum of 5 to 10 times the number of survey items should be the appropriate size for the sample. Given that there are 36 items in the survey of this study, the minimum sample size needed would be 180 subjects. The final sample size reached in this study fulfils this requirement, thus increasing credibility of findings and providing adequate statistical power for analysis.

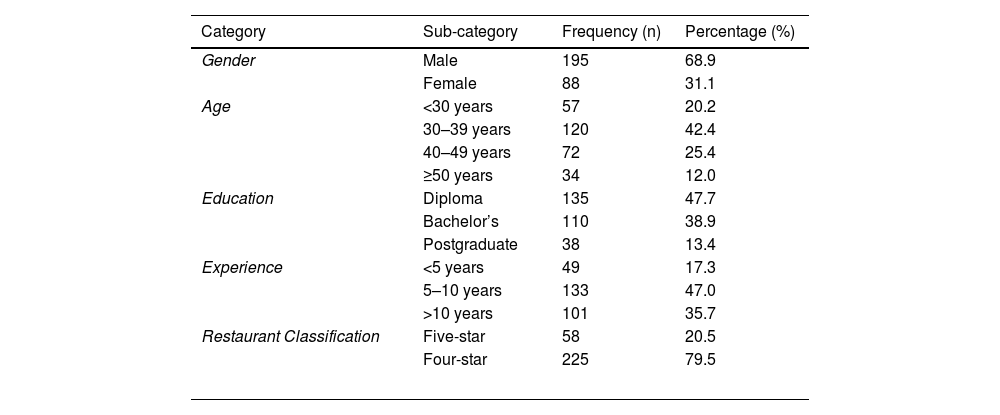

Iraq is characterised by a unique combination of Middle Eastern cultures in the context of a developing country such as the Arabic, Kurdish and Turkish. Therefore, it is expected that findings obtained from this study can be generalised to other developing countries with similar socio-cultural values and backgrounds. The labour shortage and high turnover rate in the restaurant industry make service robots a workable solution for routine job tasks (Wen et al., 2025). Robots increase efficiency, ease cost pressures and improve service quality, speed and safety - important factors when it comes to customer satisfaction (Jung et al., 2023). Adoption is shaped by perceived usefulness, trust, and risk, especially post-pandemic, when contactless service became vital (Seo & Lee, 2021). Studying this sector helps us understand the balance of technology in terms of innovation and evolving customer expectations. Restaurant managers play a central role in making decisions for innovation in the restaurant operation, such as the use of service robots. Their views represent organisational readiness and intention to implement new technologies (Wen et al., 2025). Managerial perspectives on competitive advantage, complexity and leadership support are a powerful influence on adoption decisions (Jung et al., 2023). They are aware of staff and customer dynamics and so their insights are important (Ruo et al., 2025). Managers can fully analyse the benefits, challenges, and effects of integrating CRM driven service robots. In addition, no significant differences were found in demographic characteristics of respondents. The demographic characteristics of the sample respondents are shown in Table 1.

Demographics of Study Sample.

N=283.

Source: Authors’ own work.

As presented in Table 1, 283 restaurant managers participated in this study. Of these, 68.9 % were male and 31.1 % were female. The majority were aged (“30–39″ years) (42.4 %), followed by (“40–49″ years) (25.4 %), under (30 years) (20.2 %), and (50 years) or older (12.0 %). In terms of education, 38.9 % held a “bachelor’s degree”, 47.7 % had a “diploma”, and 13.4 % possessed a postgraduate qualification. Regarding professional experience, 47.0 % had (“5–10″ years), 35.7 % had more than (10 years), and 17.3 % had less than (5 years). Additionally, 20.5 % of respondents managed “five-star” restaurants, while 79.5 % were from “four-star” establishments. These characteristics of the demographic characteristics provide evidence of an unbiased data collection process, which decreases the lack of sanctity and generalizability of the results of this study.

ResultsPreliminary screening with the use of statistical software package (SPSS v26) confirmed that there was no missing data or multivariate outliers (Mahalanobis D2 p > 0.001). Normality statistics (Skewness/ Kurtosis) were within acceptable limits (±2) – see Appendix 1Table A3. The analysis of the data was performed with PLS-SEM in SmartPLS v3.9. The analysis included two sequential but integrated stages, which were also performed within the framework of PLS-SEM: In the first stage, we evaluated the measurement model in terms of the reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity of all constructs. This included analysing the factor loadings, Composite Reliability (CR), Cronbach's alpha, Average Variance Extracted (AVE), Cross-Loadings analysis, Fornell's Larcker criterion and HTMT ratio, as per the guidelines of Hair et al. (2022). Second, we tested the hypothesised causal relationships among the dimensions of the UTAUT3 framework and BI using a structural model. This included assessing path coefficients, significance level (using bootstrapping), effect sizes (f2), coefficient of determination (R2), and predictive relevance (Q²).

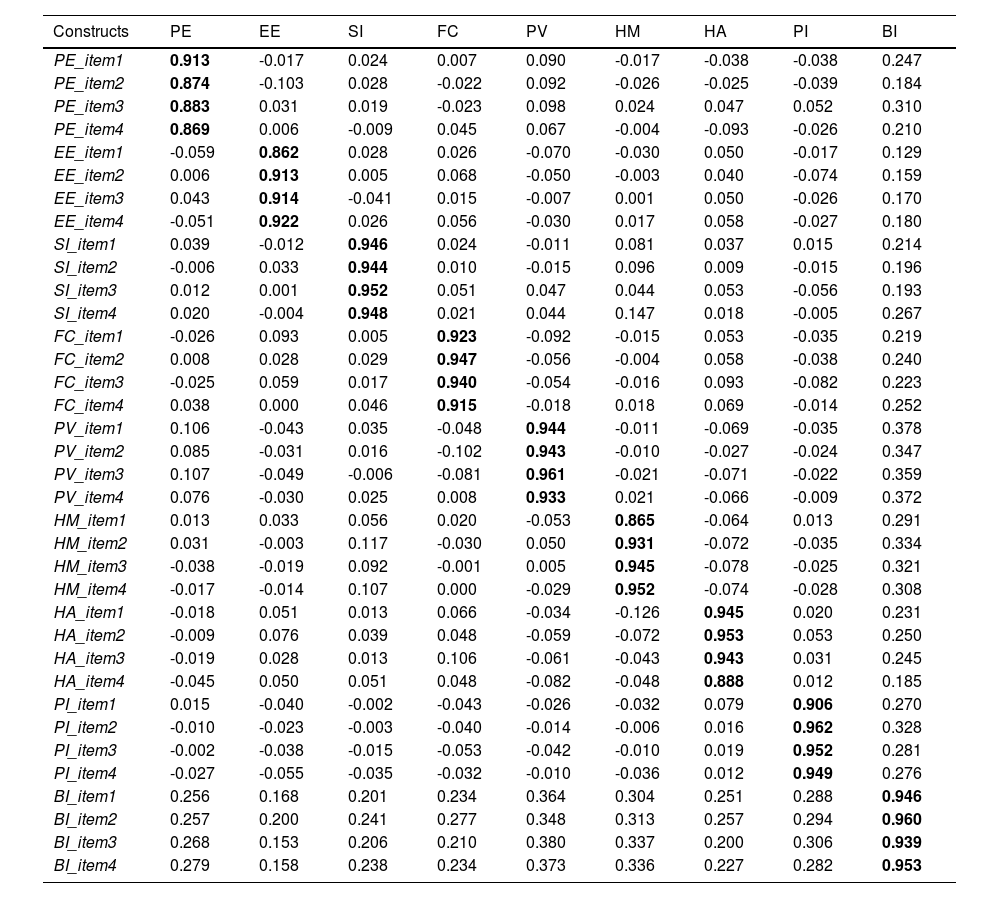

Measurement modelThe measurement model (known as the outer model) was evaluated for indicator reliability (reflective factor loadings > 0.7), convergent validity (assessed using AVE > 0.5), internal consistency (assessed using Cronbach’s alpha > 0.7 and CR > 0.7), and discriminant validity (assessed using Cross-Loadings analysis, Fornell-Larcker criterion, and HTMT ratio) according to Hair et al. (2022). Table 2 presents the items loadings (0.862–0.962 > 0.7), Cronbach’s alpha (0.909–0.963 > 0.7), CR (0.935–0.973 > 0.7), and AVE (0.783–0.901 > 0.5) for each latent construct (i.e., PE, EE, SI, FC, PV, HM, HA, PI, and BI). The results confirmed the reliability of measurement models (constructs and items). Therefore, no construct items were removed, ensuring the reliability of indicators and convergent validity (Borghi & Mariani, 2022; Fornell & Larcker, 1981). These findings are also in line with the values reported by other studies (e.g., (Abdulmuhsin, Dbesan, et al., 2025; Farooq et al., 2017; Venkatesh et al., 2012).

Items Reliability and Convergent Validity.

Source: Authors’ own work.

In terms of discriminant validity, the Fornell-Larcker criterion (requires that the square root of AVE values should be higher than the maximum value of constructs’ correlations with any other construct involved in the theoretical model) and the HTMT matrix (requires that all values within this matrix should be <0.85) in Table 3 indicate discriminant validity among the nine study variables (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Hair et al., 2022; Henseler et al., 2014). Additionally, the cross-loading in Appendix 1, Table A4, confirms the discriminant validity of all constructs. This analysis shows that each item has a higher loading with its own underlying construct, which fulfils the criterion described by Hair et al. (2022) and Rehman et al. (2025). Thus, there is no issue of discriminant validity.

Constructs’ Discriminant validity.

Notes: Bold number= √AVE, Italic number=HTMT.

Source: Authors’ own work.

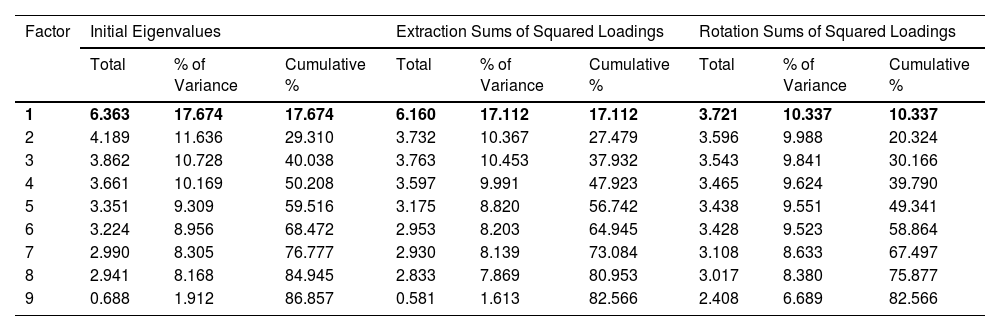

The results of the multicollinearity diagnostics confirm that multicollinearity is not a concern in this study. Specifically, all Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values for the predictor variables are well below the commonly accepted threshold of 5, according to O’brien (2007), with the highest Inner VIF and Outer VIF observed at 1.019 and 2.609, respectively. Additionally, the Tolerance values for all predictors are above 0.2 - see Appendix 1, Table A3 - further supporting the absence of problematic collinearity (Kutner et al., 2004; Menard, 2002). As shown in the Appendix 1Table A5, the single-factor analysis further corroborates this finding, as the majority of the variance is not attributable to a single underlying factor; this is indicated by the fact that the largest eigenvalue accounts for less than 50 % of the total variance, and no single factor dominates the explanatory power among the predictors (Hair et al., 2010). Taken together, these results show clear evidence that multicollinearity is not a problem, and hence we can confidently interpret the regression coefficients.

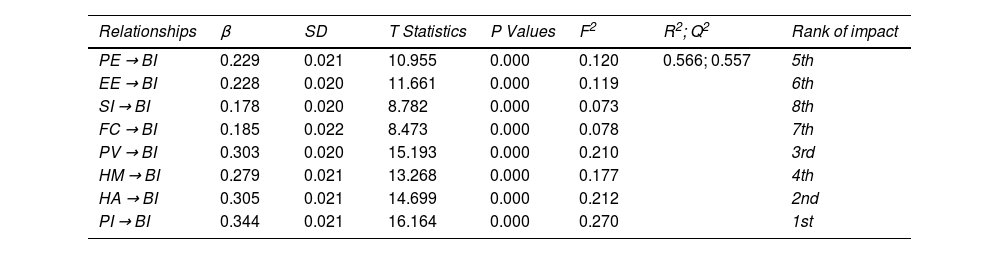

Structural model and hypothesis testingAfter validation of the measurement model, the structural model was estimated to see how the latent variables are related. Fig. 2 presents the structural model, showing the values of the beta-coefficients for the dependent variables and outer loadings and the R2-coefficients. The goodness-of-fit of the model estimated is presented in Table 4. Finally, a bootstrapping analysis was performed on a subsample of 5000 resamples to measure the direct effects of all relationships. Table 4 also summarises the results of hypothesis testing which showed that all the relationships relating to the adoption of CRM-driven service robots were supported. The path coefficients, t-values and p-values lend great support for the proposed hypotheses.

The path analysis of study model.

Note: β = Standard regression, SD = Standard Deviation.

NFI = 0.947, SRMR = 0.022.

Source: Authors’ own work.

PI emerged as the strongest predictor of BI (“PI → BI”, β = 0.344, f² = 0.270). This highlights the pivotal role of Iraqi restaurant managers’ individual characteristics in determining the adoption of CRM-driven robots. HA was the second most influential factor (“HA → BI”, β = 0.305, f² = 0.212), suggesting that previous routines involving similar digital tools or automated systems encourage future use of CRM-driven robots. PV had a substantial impact on adoption intention (“PV → BI”, β = 0.303, f² = 0.210), highlighting those managers’ perception that CRM-driven robots offer considerable benefits relative to their cost or effort. HM exerted a substantial effect on intention (“HM → BI”, β = 0.279, f² = 0.177), suggesting that the enjoyment and emotional satisfaction derived from using CRM-driven robots positively influence the restaurant managers’ adoption behaviour. PE significantly influenced BI (“PE → BI”; β = 0.229, f² = 0.120), confirming that managers value the productivity and efficiency benefits of CRM-driven robots. EE had a moderate positive impact (“EE → BI”, β = 0.228, f² = 0.119), indicating that ease of use remains a significant concern, especially in the early stages of adoption. The availability of resources and organisational support also had a notable effect on BI (“FC → BI”, β = 0.185, f² = 0.078). Finally, although SI was the weakest predictor (“SI → BI”, β = 0.178, f² = 0.073), it remained statistically significant.

The current study model was found to have excellent fit indices with NFI = 0.947 that significantly surpassed the commonly accepted threshold of 0.90 and is close to the excellent fit criterion of 0.95 recommended in PLS-SEM literature (Hair et al., 2022). The SRMR value of 0.022 suggests that there is an outstanding absolute fit, as this is well below the high requirement of 0.05 for perfect fit, and well above the acceptable requirement of 0.08 (Abdulmuhsin et al., 2024; Niaz et al., 2021). These fit statistics collectively show that the proposed model of UTAUT3 is capable of faithfully reproducing the observed correlation matrix and it has superior incremental fit as compared to the null model, providing strong credibility in method usage for the study analysis. The model used in the present study has a considerable explanatory power as the R2 value is equal to 0.566, which means that the eight constructs of the UTAUT3, explain 56.6 % of the variance in BI in the case of Iraqi restaurant managers. According to the established guidelines for the use of PLS-SEM, this ranks as a moderate-to-substantial level of explained variance that lies between the 0.50 threshold of moderate explanatory power and the threshold of 0.75 for substantial explanation (Asad et al., 2022; Hair et al., 2010). The high predictive relevance, as measured by Q2, is 0.557, which increases the usefulness of the model to predict BI, and is significantly larger than the null hypothesis of zero, indicating a good in-sample predictive relevance (Alshaher et al., 2022).

DiscussionThis paper explores the attitude of restaurant managers to the adoption of Customer Relationship Management (CRM)-driven service robot in Iraq using UTAUT3 in the food service setting. The results suggest an interesting interaction among the factors of technology adoption in Iraqi restaurant industry and PI is the most power predictor followed by HA, PV and the other constructs under the framework of UTAUT3.

The results of this study demonstrate both similarities and differences with findings from research worldwide and in the region of study (the restaurant and hospitality sector) on technology adoption. A meta-analysis on the impact of PI on technology adoption in hospitality and tourism sectors has found that there is a significant positive effect of PI, indicating the effect size was 0.38 (Ciftci et al., 2021). This means that high PI individuals are more likely to adopt new technologies, which supports the current study finding, in which PI was the best predictor of BI. In contrast, certain international studies have identified PE as the major determinant of technology adoption intention on consistent basis. For instance, Jeon et al. (2020) An Investigation into restaurant self-service technology acceptance discovered that PE was the most significant acceptance intention driver, followed by EE and SI. Likewise, ÖZekİCİ (2022) A Study on humanoid robots in restaurants (n = 363) showed that FC was the best predictor of BI followed by PE and SI, which is less similar to the current study results showing that FC was among the last predictors. Moreover, PI has few direct comparisons in the literature in the region as most of the research in the Middle East has concentrated on traditional UTAUT constructs as opposed to individual difference variables. However, Bulgiba et al. (2015) Research in Saudi Arabian private hospitals using UTAUT showed that individual characteristics and organizational readiness were crucial factors in technology adoption. However, they did not specifically examine PI as a construct. The prominence of PI in this study supports Rogers (2003) Diffusion of Innovation Theory which emphasises the power of innovativeness during the early stages of adoption. Iraqi managers with higher PI are far more likely to embrace CRM-driven service robots, even when there are not strong organisational or social drivers. These findings indicate that the hospitality industry is still in an early stage of adoption, and have practical implications for hospitality vendors, training programmes, and recruitment strategies that seek and cultivate innovative managerial profiles. This has resonated with Gajić et al. (2024), who determined that how managers evaluate robots is based on how well they align with organisational vision and innovation strategy. Likewise, Kervenoael et al. (2020) Supported this by stating that perceived technological advancement and collaborative capabilities improve competitive positioning. Iraqi managers' innovation-oriented outlook is therefore part of a worldwide phenomenon in which perceived innovativeness tends to produce a momentum of initial adoption.

The finding of HA emerging as the second strongest predictor is a unique result relative to other world studies where HA is generally a weaker influence (Du & Haith, 2023). Its large effect shows the importance of past digital experience in determining technology adoption, supporting the idea of 'technology readiness'. This effect also speaks to the notion that the use of technology can become automatic over time and will become less of a cognitive effort for decision-making (Venkatesh et al., 2003). Iraqi restaurant managers who are savvy with digital tools - e.g. POS systems or online ordering platforms - seem to be more open to CRM driven service robots. There is an implication that this sector has been slowly digitalising so that the managers become comfortable using technology. The prominence of HA suggests that the cumulative exposure to digital solutions, both in restaurants but also in society in general, supports higher levels of openness to innovation. Similar evidence was presented by Gajić et al. (2024) and Ivkov et al. (2020) who showed that the previous technology experience and established innovation practises have an influence on managerial adoption behaviour. Ding et al. (2023) Went further to say that organisational routines surrounding technology change influence the decision-making process. These are the parallels observed in order to reveal the cumulative digitalisation exposure of Iraqi managers that can powerfully catalyse a HA-related openness to robotic solutions. However, the marked role played by PV in the Iraqi context is consistent with evidence in other developing economies. However, it is different from what has been found in developed countries where economic factors are less important (Verma et al., 2024). Similar to the research by Pande and Gupta (2022), which took place in India, this case brings up the importance of considering the costs and benefits of adoption choices. The substantial effect size of PV can be explained by financial realities of the Iraqi restaurant industry where investment decision is well considered and financed by a strong financial mentality. Iraq Restaurant Managers Seem Extremely Profitable to the Economic Value Proposition of CRM Driven Service Robots Adoption by Iraqi Restaurant Managers looks like a strategic investment, not a standard business operation decision. These findings agree with the findings of Aliyu and Beyioku (2025) who identified cash flow management, return on investment as the most important criteria for managers when assessing robotic technologies. Lin et al. (2025) Also named installation and maintenance costs as important obstacles. For this reason, the Iraqi case can be located within a wider managerial logic according to which the adoption of technologies in cost-sensitive sectors is governed by economic rationality.

The high impact of HM in the present work is consistent with global trends and helps to highlight the role of emotional and experiential factors in technology adoption. Findings are consistent with the work of Ozturk et al. (2023), who implemented a work conducted in several countries, which emphasised the influence of perceived enjoyment in combination with value as it related to function. In the Iraqi context, the HM's prominence indicates that service robots are not only viewed as operational tools, but they are also considered as means of professional pride and satisfaction in accordance with Guan et al. (2021) research on using robots in restaurants. Ranked fourth out of the strongest predictors, HM suggests that although emotional satisfaction is important it is a complement and not a replacement for rational economic considerations. Kervenoael et al. (2020) Found that hedonic factors such as guest enjoyment, novelty and marketing potential bring higher managerial interest in adopting. Lin et al. (2025) identified that managers draw a line between trial adoption for novelty and operational value. Similarly, Iraqi managers appear to view hedonic worth not in terms of entertainment but in terms of pride in the profession and customer attraction. The reasonable nature of PE influence in the present study is in contrast to findings worldwide for which PE is often the best predictor of adoption (Khechine et al., 2016; Rybizki et al., 2022). While international research, such as Guan et al. (2021) on robot restaurants and Awwad and Al-Jaafreh (2015) on the MENA region, emphasise performance as central, Iraqi managers seem to consider the efficiency gains, among other factors. The medium effect size suggests that although improvements in productivity and service are appreciated, these are not decisive factors in terms of adoption. This suggests that performance improvements, while required, need to be clearly shown and supported by other drivers of motivation. This is in contrast to the results of Gajić et al. (2024)who demonstrated that managers initially consider service robots in view of expected operational benefits (e.g., efficiency, cost reduction). Similarly, Lin et al. (2025) concluded that ROI expectations and functional value appraisals are very important in long term adoption. In comparison, Iraqi managers appear to value such performance benefits and balance them with hedonic and economic ones.

The similar effects of EE found in this study are consistent with findings from researchers across the world, where ease of use has been consistently found to be a salient factor, especially during the early stages of adoption (Khechine et al., 2016). Research on robotic process automation likewise shows that EE has a significant influence on acceptance intentions, and is a reflection of individual preferences for technologies that are simple to learn and operate (Kim et al., 2022; Kim & Hong, 2024). The moderate positive influence of EE points to persistent usability issues. Its medium effect size indicates that the Iraqi restaurant managers still don't trust much in service robots as they consider usability just as significant as functionality. This is consistent with Ding et al. (2023) who found that managerial adoption decisions are affected by perceived implementation complexity and technical interoperability. Similarly, Aliyu and Beyioku (2025) found that managerial behavioural intention is significantly influenced by ease of integration and maintenance requirements and the same was echoed by Iraqi managers when considering CRM-driven robots. Regional research highlights the importance of FC and organisational support, although the extent to which they affect this varies (Buyan et al., 2023). In this study, FC had moderate effect which means that while organisational readiness factors such as infrastructure, training and ongoing support is important, it is not decisive in Iraqi context. This might be an indication of the early phase of CRM driven service robot adoption, where decision-making is carried out individually rather than institutionally. Organisational capacity is one facet of adoption that managers take into consideration when assessing the adoption of a technology based on the small to medium effect size, however, FC works more as an enabling condition than primary driver, whose commitment goes beyond the initial investment. A study by Ding et al. (2023) similarly identifies technical infrastructure, training capacity, and maintenance support as key enabling factors. Gajić et al. (2024) Go on to say that failure to change management and fragmented implementation can result in failure. This comparison would point out that while Iraqi managers know about these conditions, they operate in a resource constraint condition that limits what can be done/implemented under FC. Finally, the low influence of SI in the current study has been contrasted with expectations influenced by Middle Eastern cultural contexts where collective norms and peer pressure are usually more prominent. Awwad and Al-Jaafreh (2015) Research in MENA region also showed that SI was not significant, which supports current findings. International evidence, however, is mixed; for example, Tomić et al. (2022) found that SI is a good determinant of Serbian electronic tool adoption. The small but significant impact here indicates that Iraqi restaurant managers are more focused on individual and economic considerations than social expectations, although SI may be more important as the adoption of SI develops. In other settings, Kervenoael et al. (2020) stated that managers are exposed to high social pressures such as expectations from guests, influence from stakeholders, and trends in the industry. Ivkov et al. (2020) Also found that competitive position and guest experience expectations affect adoption in hospitality industries. The lesser impact on Iraq points to the lesser institutionalisation or relevance of SI processes in early stage markets.

Theoretical and practical implicationsThis study has made a number of theoretical contributions to the technology adoption literature. First, it extends the UTAUT3 framework by showing an important role of PI in the Iraqi restaurant sector. The dominance of PI challenges the assumption that traditional UTAUT constructs, such as (PE and SI) universally drive adoption. Instead, in emerging markets and situations of early adoption, individual characteristics may be more important than organisational or social influences. Second, the results underscore the importance of HA formation and HM via emotional and experiential factors as part of the adoption decision, in keeping with changing attitudes in adoption theory. Third, the influence of PV is strong, reinforcing the importance of economic rationality for economic development in developing economies, suggesting that economic reasoning is a key determinant in which resource constraints are apparent. Collectively, these results suggest that technology adoption models need to be adapted culturally, and that they need to be adapted contextually, especially when applied in developing markets and new industries.

From a managerial and industry perspective, the findings have a number of practical implications. For technology vendors, marketing strategies should be focused on innovative managers as early adopters, and should promote the functional and hedonic benefits with some form of convincing evidence that it is a good return on investment. Flexible pricing models and living case studies may help to overcome financial barriers. For restaurant owners and managers, adoption strategies should focus on taking advantage of existing digital habits, strong training, and a visionary, fit for purpose, implementation linked to organisational readiness. It is emphasised that clean, enjoyable and rewarding user experiences will further promote acceptance. For policymakers and industry associations, the findings suggest the need to increase the technological infrastructure, create an innovation culture, and provide financial incentives to address cost issues. Platforms for knowledge exchange and sharing of best practices could lead to increased speed of adoption. Together, these measures create a multiple dimensional approach in the advancement of integration of service robots in the Iraqi restaurant industry.

Conclusion, limitations, and future researchThis study aimed to investigate the intentions of Iraqi restaurant managers to adopt the CRM approach to use service robots with the UTAUT3 framework to uncover a complex interplay among the factors at individual level, economic level, and organisational level. PI was found to be the most important predictor of adoption, followed by HA, PV and HM, PE, EE, FC and SI were comparatively moderate and weak predictors, respectively. These results highlight a distinctive style of adoption, based on individual characteristics and financial and experience-related motivations, providing new knowledge on technology acceptance in the emerging economies. The study adds to both the theory and the practice of vendor, practitioner and policymaker.

The study has its limitations despite its contributions. First, the design is cross sectional, which hinders the capability to measure change in adoption behaviour over time. Second, there is the risk of biases because of using self-reported data (social desirability and standard-method variance). Third, the generalisability of the findings is reduced by the targeting of CRM-driven robots since there are various types of automation that can have different drivers of adoption. Lastly, the sample, which comprised managers of four-star restaurants and above, is not a representative sample of the restaurants in the whole country of Iraq, especially smaller or less digitally advanced restaurants.

These limitations may be overcome in future studies in a number of ways. It would be useful to conduct longitudinal studies to trace changes in BI and real usage over time, especially as the adoption of the service robots continues to reach an early and late phase. Comparative analysis between different economies in the Middle East and developing countries could reveal some common and divergent patterns in adoption that would enhance the situational knowledge. Also, a study of moderating variables - restaurant size, ownership structure, or the level of technological preparedness, to name a few - would help identify under what circumstances particular predictors are more or less significant. Lastly, the model can be further improved by adding barriers and inhibitors like perceived risks, ethical issues, or job-displacement fears, which would present a more comprehensive explanation of the adoption processes.

CRediT authorship contribution statementMustafa Obay Saeed: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Amir A. Abdulmuhsin: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Software, Resources, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Dima M. Dajani: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Conceptualization.

Literature Review on Service Robot Adoption (2020–2025).

| Study | Context / Country | Key FactorsOR Theory | ContributionsOR Novelty | StudyLimitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ghazali et al. (2025) | Restaurant customers with robot experience; n = 308 real-world customers; Post-adoption engagement focus | Integrated S-O-R framework with USUS model; Functional, emotional, and relational dimensions of customer experience | First study integrating S-O-R and USUS frameworks for robot service evaluation; Focus on post-adoption engagement rather than initial acceptance; Identifies paradoxical effects of enjoyment and friendliness on revisit intention | Customer-focused rather than managerial perspective; Limited to restaurant context; Cross-sectional design; May not capture long-term relationship dynamics |

| Moliner-Tena et al. (2025) | Spanish hotels; Experimental study with two robots (Tokyo, Nairobi); Natural environment testing | Inductive Inference Theory of Anthropomorphism; Expectancy Disconfirmation Paradigm; Memorable Customer Experience (MCE) framework | First experimental study comparing robots with different anthropomorphic features in real hotel settings; Demonstrates positive impact of robot presence on MCE; No evidence of uncanny valley effect | Limited to two hotels and two robot types; Small subsamples for hotel-robot combinations; Challenges in integrating qualitative and quantitative data; Geographic limitation to Spain |

| Huang and Lo (2025) | Hotel check-in scenarios; n = 396 Chinese respondents; Service failure context analysis | Mind Perception Theory, Attribution Theory, Expectancy Disconfirmation Theory; Service failure recovery framework | First study examining customer responses to service failures by different types of service provider agents (human, humanoid, non-humanoid robots); Identifies differential forgiveness and recovery expectations | Scenario-based rather than real-world experience; Limited to Chinese context; Focus on failure scenarios may not represent normal operations; Hotel check-in specific context |

| Figueiredo et al. (2025) | Restaurant customers; n = 415 validated responses; Robot waiter acceptance and continuous use | Extended TAM with hygienic handling, innovativeness, enjoyment, trust, risk, willingness to pay constructs | Introduction of hygienic handling as new TAM construct; Focus on continuous use rather than initial adoption; Practical marketing strategies for managers | QR code distribution challenges; Only 52.6 % had actual robot restaurant experience; Cultural and socioeconomic factors may limit generalizability; Limited manager participation in study design |

| Marghany et al. (2025) | UK hotel guests; n = 358 online surveys; Developed market context | Meta-UTAUT model plus anthropomorphism, aesthetics, interaction, trust; AMOS-SEM analysis | Large-sample empirical validation of extended UTAUT model in hospitality context; Identifies negative effect of effort expectancy on intention; Provides actionable insights for hotel managers on guest acceptance factors | UK-specific findings may not transfer to Asian/developing markets; Customer acceptance focus with indirect managerial implications; Cross-sectional design limits causal understanding |

| Xu et al. (2025) | Frontline hotel employees; Organizational dehumanization perspective; Employee impact study | Coping theory framework; Organizational dehumanization as mediating variable; Employee threat perception and response mechanisms | First study to examine negative impacts of AI service robots on frontline employees through dehumanization lens; Provides critical insights for managers on employee resistance and coping strategies | Limited to frontline employee perspectives; May not capture full spectrum of organizational impacts; Geographic scope unclear; Focus on negative impacts may bias findings |

| Wu et al. (2025) | Hotel employees; Multi-dimensional impact assessment; Employee attitude and emotion focus | Multi-dimensional framework examining attitudes, emotions, and behavioral responses; Sustainable technology adoption perspective | Comprehensive examination of employee responses to service robot implementation; Provides framework for managers to assess and manage employee reactions; Emphasizes sustainability aspects | Employee-focused rather than managerial decision-making; Limited sample size details; Sustainability focus may not address immediate implementation challenges |

| Gong (2025) | Hospitality industry employees; Perceived fairness in robot implementation; Dysfunctional behavior outcomes | Perceived fairness theory; Unexpected negative consequences of fair implementation practices | Counterintuitive findings showing how perceived fairness can lead to employee dysfunctional behavior; Critical insights for managers on implementation communication and change management | Focus on negative behavioral outcomes; Limited geographic and industry scope; May not represent typical implementation scenarios |

| Seo and Lee (2025) | Robotic restaurants; Service quality and customer satisfaction; Sustainability perspective | Service quality framework; Perceived value, restaurant image, satisfaction, revisit intention relationships | Empirical validation of service quality impacts in robotic restaurants; Provides managers with performance metrics for robot service evaluation; Integrates sustainability considerations | Restaurant-specific findings may not generalize to broader hospitality; Limited methodological details; Sustainability focus may not address core implementation challenges |