Green technology innovation (GTI) is crucial for enhancing the resource utilization of construction and demolition waste (CDW). However, consumer resistance to products made from recycled CDW significantly constrains their advancement. Existing studies largely emphasize government policies and technological progress, while the pivotal influence of consumer innovation resistance remains underexplored. This study applies evolutionary game theory, grounded in innovation resistance theory, to examine the long-term interactive dynamics between consumers and building material manufacturers (BMMs). The results reveal that (1) both consumers’ stronger willingness to purchase green innovative products and BMMs’ higher initial intention to adopt GTI foster sustainable green development; and (2) the degree of consumer innovation resistance exerts heterogeneous effects on BMMs’ GTI decisions, whereas consumer green preferences consistently stimulate GTI adoption. Overall, this study elucidates the evolutionary mechanisms through which consumer innovation resistance and green preferences affect BMMs’ GTI behavior, addressing a key gap in the CDW domain. It further offers theoretical guidance for enterprises to mitigate innovation resistance, refine GTI strategies, and advance sustainable innovation in the construction industry.

With the rapid pace of global urbanization, the generation and environmental impact of construction and demolition waste (CDW), an unavoidable byproduct of infrastructure expansion, are steadily intensifying (Lyu et al., 2025; Sarkodie et al., 2020). The World Bank projects that the global CDW output will reach 3.4 billion tons annually by 2025, a substantial increase from 2.01 billion tons in 2018 (Gao et al., 2024). In several developed and developing nations, CDW growth rates have reached approximately 19% and 40%, respectively (Selvam et al., 2025). The situation is particularly concerning given the high proportion of CDW in total waste generation—for instance, CDW constitutes approximately 32% of total waste in the United Kingdom and between 50% and 70% in Brazil (Schmidt et al., 2025; Kravchenko et al., 2024). The massive accumulation of CDW not only occupies valuable land resources but also results in wasted energy and environmental degradation. Consequently, this escalating challenge amplifies the conflict between economic growth and ecological sustainability. In response, several countries have introduced targeted strategies to mitigate CDW-related issues. For example, Australia and the United States have developed waste flow networks to promote CDW recycling (Moschen-Schimek et al., 2023). Similarly, the European Union has integrated a 70% CDW recycling target into its Waste Framework Directive, emphasizing the recovery of energy from waste and the reduction of resource loss (Huang et al., 2021a). Despite these concerted efforts, global CDW recovery rates remain relatively low (Menegaki & Damigos, 2018). Therefore, enhancing the efficiency of CDW processing and resource utilization remains an urgent and ongoing global priority.

Past studies have categorized the management of CDW into two primary approaches: landfilling and recycling (Yazdani et al., 2021). Among these, recycling offers distinct advantages over landfilling, as it enables the production of recycled products through green technological innovation (GTI), thereby enhancing resource recovery and energy efficiency. This method simultaneously reduces resource conversion costs and conserves land for new construction projects (Bai & Wang, 2020; Tam, 2008). Consequently, building material manufacturers (BMMs) and related enterprises have increasingly adopted GTI to produce remanufactured CDW products that improve both economic performance and market competitiveness (Shao et al., 2023). For example, Ningbo Pinghai Building Materials Co., Ltd. has implemented GTI processes to convert solid construction waste into energy-efficient and environmentally friendly building materials. The resulting remanufactured products have been certified as green innovations, thereby expanding market demand (Department of Housing and Rural‒Urban Development of Zhejiang Province, 2024). This development not only strengthens resource utilization and GTI advancement but also aligns with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for industrial innovation. Therefore, investigating the GTI behavior of BMMs is crucial for improving CDW management and achieving sustainable industrial transformation.

The adoption of CDW recycling technologies is reshaping corporate production strategies while simultaneously influencing consumer behavior. Some consumers demonstrate green purchasing preferences, express positive attitudes toward the environmental value of eco-friendly products, and show a willingness to support GTI initiatives (He et al., 2019). However, drawing on innovation resistance theory, not all consumers readily accept innovative products (Datta et al., 2015). This reluctance is particularly evident in the CDW market, where consumer awareness of products remanufactured through GTI remains limited, generating concerns about product reliability and usability (Sitcharangsie et al., 2019). Furthermore, the high cost of CDW recycling undermines the price competitiveness of green remanufactured products, leaving them at a disadvantage compared with traditional alternatives (Guidice et al., 2025). Consequently, even consumers who prefer sustainable products may resist purchasing CDW-based goods produced via GTI due to cognitive biases and price differentials. Such consumer resistance leads to reduced market acceptance and constrains the profitability of building material manufacturers (BMMs), heightening the risk of unsold inventory (Holweg et al., 2016). This, in turn, weakens enterprises’ incentives for continued GTI adoption. Therefore, examining how consumer innovation resistance influences the GTI behavior of BMMs is essential for understanding the barriers to sustainable industrial transformation.

Moreover, BMMs are motivated to adopt GTI not only by government incentives but also by their own commitment to corporate environmental responsibility (Qian et al., 2023). As a key factor in CDW resource management, the government encourages BMMs to engage actively in GTI through policy guidance and targeted incentive programs aimed at advancing the sustainable use of environmental resources (Yan, 2025). Additionally, governments have developed dynamic and context-specific interventions to stimulate GTI behavior across different regulatory and industrial scenarios (Liu et al., 2023).

In summary, previous research has mainly examined the current state of CDW treatment and explored the roles of multiple factors, such as green technology application, consumer green preferences, and government subsidies, in promoting its recycling. However, most of these studies adopt factor-based or policy-oriented approaches, overlooking consumer innovation resistance as a critical variable. In fact, such resistance may weaken manufacturers’ long-term innovation capacity. How do different levels of consumer resistance affect the evolution of BMMs’ GTI behavior? Moreover, what role do consumer green preferences play in shaping the dynamic evolution of GTI among BMMs? To address these questions, this study applies evolutionary game theory to analyze how consumer innovation resistance influences the GTI decisions of BMMs in the CDW context.

The innovations of this study are as follows. First, although several studies have applied innovation resistance theory to explain consumer resistance to new technologies or products, most have concentrated on domains such as fintech (Verma et al., 2023; Uddin et al., 2025). Currently, no research has incorporated the perspective of consumer innovation resistance into the CDW field. This study introduces this perspective into the CDW remanufacturing context, analyzing consumer resistance behaviors toward such products and their impact mechanisms within the building materials supply chain. This approach not only enriches existing research on CDW recycling and consumer innovation resistance but also extends the theoretical boundaries of innovation resistance in the building materials sector. Second, previous studies have focused on the relationships among government subsidies (Han et al., 2024), consumer green preferences (Li et al., 2025), and corporate GTI behavior while neglecting the key role of consumer innovation resistance. Specifically, the conditions under which the degree of consumer resistance influences manufacturers’ GTI adoption decisions remain underexplored. Moreover, existing studies largely rely on traditional empirical approaches or static models of conventional government behavior. To date, no research has applied evolutionary game theory to examine the long-term interactions between consumer innovation resistance and green preferences in shaping the GTI behavior of BMMs. This study fills these gaps by incorporating consumer innovation resistance and green preferences as core variables, with government subsidies as a default variable, to construct an evolutionary game model involving consumers and BMMs. The model reflects consumers’ evolving innovation attitudes and offers BMMs valuable evidence for designing innovative products and formulating effective market strategies.

This study is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews the literature on CDW resource utilization, consumer innovation resistance, and GTI. Section 3 develops the model on the basis of innovation resistance theory (IRT) and the evolutionary game approach. Section 4 identifies the equilibrium points and analyzes their stability conditions. Section 5 conducts numerical simulations of key parameters to explore their effects on the game’s evolutionary trajectory. Section 6 summarizes the research findings and provides insights for promoting green innovation among BMMs.

Literature reviewThis section reviews three main themes: CDW resource utilization, consumer resistance to innovation, and GTI. This highlights the research gaps between this study and prior literature (Table 1) and explains how the present study addresses them.

The differences between prior studies and this study.

| Sources | Government subsidies | Consumer green preference | Consumer innovation resistance | CDW | GTI | Evolutionary game |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wang et al., 2024 | ˟ | ˟ | ˟ | ✓ | ˟ | ˟ |

| Zeng et al., 2025 | ✓ | ˟ | ˟ | ✓ | ˟ | ˟ |

| Barman et al., 2021 | ✓ | ✓ | ˟ | ˟ | ✓ | ˟ |

| Han et al., 2022 | ✓ | ✓ | ˟ | ✓ | ˟ | ˟ |

| Tang et al., 2025 | ˟ | ˟ | ✓ | ˟ | ˟ | ˟ |

| Goel et al., 2021 | ✓ | ˟ | ✓ | ˟ | ˟ | ˟ |

| Jalu et al., 2024 | ˟ | ✓ | ˟ | ˟ | ✓ | ˟ |

| Kautish et al., 2024 | ˟ | ✓ | ✓ | ˟ | ˟ | ˟ |

| Wang et al., 2025a | ˟ | ˟ | ˟ | ˟ | ✓ | ˟ |

| Han et al., 2024 | ✓ | ˟ | ˟ | ˟ | ✓ | ˟ |

| Khan et al., 2022 | ˟ | ˟ | ✓ | ˟ | ✓ | ˟ |

| Wu et al., 2025 | ✓ | ✓ | ˟ | ˟ | ✓ | ✓ |

| This study | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

CDW refers to the mixed waste generated during building construction and demolition activities. Accordingly, governance strategies and CDW processing methods have received increasing attention from scholars. Internationally, some countries focus on recycling systems and the economic drivers of CDW treatment (Lockrey et al., 2016; Di Maria et al., 2018), whereas others emphasize posttreatment reuse by converting CDW into recycled aggregates and construction materials (Kanda, 2022; Santolini et al., 2023). In many developing countries, CDW production is high, its growth is rapid, and treatment methods remain simple and outdated (Zhou et al., 2023). Therefore, optimizing CDW recycling can reduce landfill accumulation, mitigate ecological pressure, and significantly contribute to sustainable development (Kravchenko et al., 2024). However, immature recycling technologies (Wang et al., 2024), weak sales of remanufactured products (Werner-Lewandowska et al., 2025), inadequate waste classification implementation, and insufficient government incentives have reduced enterprise participation (Guo & Chen, 2022; Huang et al., 2025). Collectively, these challenges have constrained the expansion of the CDW recycling industry.

To increase enterprise resource utilization technology, governments have introduced incentive measures such as increasing subsidies, allocating GTI project funds, and implementing combined policy instruments (Han et al., 2024). The effects of these incentives vary according to subsidy types and target recipients. Studies show that government subsidies can indirectly shape consumer green preferences, thereby promoting corporate resource recovery. Barman et al. (2021) demonstrated that subsidies for green products can lower prices, stimulate demand for green consumption, and encourage enterprises to improve the performance of their own green products. Moreover, subsidies directed at manufacturers’ R&D costs positively affect CDW recycling (Zeng et al., 2025; Shao & Chen, 2022). Notably, compared with consumer subsidies, direct subsidies to manufacturers more effectively strengthen corporate GTI motivation and resource recovery outcomes (Safarzadeh & Rasti-Barzoki, 2019).

On the other hand, consumers’ perceived green value strongly influences their purchasing choices. They tend to focus on product functionality, preferring high-performance green products that offer greater value (Roh et al., 2022). Empirical evidence shows that growing environmental awareness among consumers positively promotes CDW recycling (Liu et al., 2020). Accordingly, such green consumption awareness clearly positively affects CDW recycling. Drawing on these insights, Han et al. (2022) examined closed-loop supply chain decisions that integrate consumer green preferences and government subsidies, clarifying their interaction. However, most existing studies operate under an optimistic assumption that consumers readily embrace innovation, while giving insufficient attention to the negative effects of consumer resistance to new products. This omission represents a significant research gap in CDW recycling.

In general, existing research has clarified the CDW treatment process and proposed strategies to enhance recycling, particularly emphasizing the effects of government subsidies and consumer awareness. However, these studies have not directly addressed the new challenges posed by consumer resistance in practice. A notable gap remains in examining how consumer innovation resistance affects CDW resource utilization, especially regarding manufacturers’ GTI behaviors within the building materials supply chain. Therefore, building on prior studies, this research explores the behavioral relationships among these factors and their influence on advancing CDW resource utilization.

Consumer innovation resistanceConsumer innovation resistance refers to individuals’ reluctance to adopt new products or ideas. This reluctance stems from changes in consumer satisfaction with the status quo or conflicts between innovations and existing belief structures (Heidenreich et al., 2022). Innovation resistance can take two forms: proactive or passive. Consumers display active resistance after evaluating the perceived attributes of innovation, whereas passive resistance emerges instinctively as an immediate, unexamined reaction to new ideas (Shankar et al., 2024). Specifically, consumer innovation resistance arises from factors related to functional use, value perception, and traditional barriers. These factors negatively influence innovation adoption (Huang et al., 2021b; Claudy et al., 2015). Scholars have conducted extensive research in the transportation sector to compare consumer resistance levels. For example, through questionnaire surveys, Tang et al. (2025) reported that higher performance barriers increase consumer resistance to secondhand electric vehicles. However, studies also show that government support can effectively reduce such resistance toward electric vehicles (Goel et al., 2021). The interaction of these factors underscores the complexity of consumer resistance. In green product contexts, this resistance is regarded as a major obstacle that can delay or hinder new technology adoption (Khan et al., 2022).

In addition, innovation resistance serves as an intermediary between consumer perceptions and purchase intentions toward innovative products. Perceived risk reduces purchase intention, whereas perceived value enhances it (Yoo, 2021). This demonstrates the dynamic link between innovation resistance, consumer perception, and purchasing behavior. Furthermore, consumer brand loyalty lessens external influences, enabling consumers to focus on their preferred brand’s features and thereby mitigating negative perceptions of innovative products (Sun et al., 2022). Empirical evidence shows that green brand innovation and perceived value are crucial to maintaining brand loyalty when aligned with consumer expectations (Jalu et al., 2024). Similarly, enhancing consumers’ sustainability awareness, including the promotion of green preferences, can help reduce innovation resistance and strengthen their purchase intention (Kautish et al., 2024).

Overall, while prior research on innovation resistance has examined its conceptualization, antecedents, consequences, and mitigation strategies, it remains underexplored in the CDW context. Government subsidies and consumer perceptions can shape consumer attitudes toward innovation resistance. However, few CDW studies have addressed the intrinsic link between consumers’ green preferences and innovation resistance, and the potential interaction between these factors and government subsidies has been largely neglected. Therefore, this study considers consumer innovation resistance and green preferences as key determinants in analyzing GTI behaviors among BMMs. Moreover, most research on innovation resistance has relied on conventional empirical analyses of influencing factors, with limited use of evolutionary game frameworks to explore stakeholder behavioral evolution. To fill this gap, this study applies evolutionary game theory to examine the dynamic relationship between consumer innovation resistance and green preferences. This approach not only overcomes the limitations of traditional empirical methods in capturing long-term interactive mechanisms but also better represents the complexity of innovation resistance behaviors in the CDW domain.

GTIGTI emphasizes resource conservation and environmental protection, serving as a key driver of sustainable development (Bi et al., 2024). Specifically, GTI involves implementing environmentally oriented measures in traditional process design and production under resource constraints. These initiatives seek to balance economic growth with ecological responsibility (Bi et al., 2024). Enterprise capability, as a crucial enabler of GTI (Wu et al., 2022), not only promotes GTI to reduce reliance on natural resources but also supports the design and production of eco-friendly products through innovation (Bai & Wang, 2020). This process enhances productivity and competitiveness while reducing environmental risk (Wang et al., 2025a).

Studies show that consumer needs strongly influence corporate GTI behavior (Li et al., 2022a). As consumers’ environmental awareness increases, market demand for green products also increases (Gong & Dai, 2022). However, GTI failure rates remain high, with consumer resistance to innovation identified as a key cause (Kumari & Kumar, 2023). When consumers perceive that an innovative product’s functions do not meet usage expectations or conflict with existing values, they exhibit innovation resistance, which consequently inhibits corporate innovation behavior (Khan et al., 2022).

Government subsidies and consumers’ green preferences drive companies to develop innovative products and advance GTI (Wang et al., 2023; Xu & Tan, 2025). On the one hand, studies show that government subsidies promote corporate green innovation and help overcome the barriers faced during innovation transitions (Guan et al., 2019). Subsidized firms tend to invest more in innovation, and sustained subsidies exert stronger performance effects (Liu & Xu, 2024). Research on urban green innovation zones also indicates that environmental protection laws and regulations show regional variation in fostering green innovation (Li et al., 2022b). In contrast, government subsidies consistently incentivize corporate green innovation regardless of regional differences (Han et al., 2024). On the other hand, consumers’ green preferences likewise influence the diffusion of corporate innovation. Higher consumer green preferences encourage firms to adopt green marketing and strengthen their brand reputation (Li et al., 2025). They also help stabilize price competition and raise the average market value of green products (Zou et al., 2024). Hence, government subsidies directly regulate GTI behavior through financial incentives, whereas consumer green preferences indirectly shape GTI strategies among building materials enterprises (Wu et al., 2025).

While prior studies have highlighted the vital role of enterprises in advancing GTI, most have focused on how government subsidies and consumer green preferences influence corporate technological innovation. However, based on government subsidy mechanisms, no research has yet clarified the effects of consumer innovation resistance and green preferences on BMMs’ GTI within the CDW recycling sector. Therefore, this study adopts an evolutionary game approach to reveal the dynamic mechanisms through which consumer innovation resistance and green preferences affect BMMs’ GTI adoption.

Model construction and analysisResearch methodsAs a mathematical approach to analyzing decision-making processes, evolutionary game theory identifies stable strategies that adapt to complex and dynamic environments through continuous trial, imitation, and learning (Zhou et al., 2022). It has been widely applied in engineering, economics, and related fields. This method effectively describes how individuals make decisions under bounded rationality, incomplete information, and environmental uncertainty and how such decisions evolve over time.

The rapid development of products within the CDW resource framework has created a limited understanding of GTI among building material manufacturers and consumers. Environmental uncertainty restricts information flow, making it difficult for participants to achieve perfect rationality (Roca et al., 2009). For example, consumers often lack complete information about the performance and attributes of recycled products, whereas manufacturers struggle to assess market demand accurately for GTI. Evolutionary game theory provides an appropriate framework for such contexts, enabling consumers and manufacturers to simulate the CDW market under incomplete information and extending the traditional “economic man” assumption (Song et al., 2019). Moreover, when BMMs adopt GTI, they consider consumers’ resistance to green innovative products, reflecting that innovators account for external decision-making factors when making green innovation choices (Fang et al., 2019). Although traditional cross-sectional studies can analyze decision-making relationships effectively (Liu et al., 2022), their retrospective nature limits systematic modeling of CDW dynamics in multiparticipant settings. Therefore, analyzing multiagent dynamic decision-making is more suitable for evolutionary game applications.

Furthermore, evolutionary game theory can simulate realistic decision-making through continuous trial-and-error and dynamic adjustments (Zhang et al., 2024). This gives it particular value in predicting long-term strategies, especially with respect to GTI and government policy formulation (Eghbali et al., 2024). It also captures mutual deduction among participants and evolving decision-making behaviors (Li et al., 2024). For example, BMMs’ and consumers’ decisions are influenced by factors such as innovation resistance, unsalable risk, and government incentives. BMMs may adjust strategies in response to unsalable risks and innovation resistance, whereas consumers may alter attitudes on the basis of government policies and market performance. The mutual feedback of innovation resistance behavior thus justifies the use of evolutionary game theory to analyze the GTI behavior of BMMs. In contrast, traditional empirical methods, which often rely on cross-sectional or short-term panel data (Tang et al., 2025), face challenges in capturing the long-term dynamic interactions between consumer behavior and manufacturer decision-making.

It is evident that although traditional empirical methods are valuable for analyzing variable correlations and predicting trends, they fail to capture the gradual adjustment of strategies over time and cannot reveal the evolutionary mechanisms underlying decision variables. Evolutionary game theory provides a deeper analytical framework, making it more effective for uncovering behavioral evolution among stakeholders. Accordingly, this study incorporates consumers and BMMs into an evolutionary game model to examine the dynamic evolution of BMMs’ GTI behavior from the perspective of innovation resistance.

Problem description and model assumptionsThis study considers BMMs that, driven by their development goals and government subsidies, adopt GTI to produce remanufactured products. However, because consumers differ in their acceptance of new products (Venkatesh et al., 2012), many remanufacturing methods remain in their early stages, and some consumers remain skeptical about product quality (Sitcharangsie et al., 2019), resulting in resistance to these products. Yang et al. (2021) noted that consumers’ valuations of remanufactured products are uncertain and prone to regret. Similarly, Sang et al. (2022) reported that consumers exhibiting innovation resistance are generally reluctant to purchase innovative products. Therefore, both consumer innovation resistance in the market and BMMs’ hesitation in GTI decision-making warrant attention. Accordingly, this study constructs a supply chain model composed of BMMs and consumers within the CDW remanufactured product market (Fig. 1).

The supply chain model shown in Fig. 1 involves the government, BMMs, and consumers. Its framework is described as follows:

The government shapes the external environment and encourages BMMs to make GTI decisions through subsidy policies.

BMMs determine their level of GTI investment on the basis of government subsidies and consumers’ innovation attitudes. Their strategic options include innovation (adopting GTI) and non-innovation (not adopting GTI).

Consumers purchase either remanufactured or conventional products produced by BMMs in the CDW market. However, owing to innovation resistance, some consumers exhibit resistance behavior, whereas others do not, reflecting internal differences in adoption attitudes.

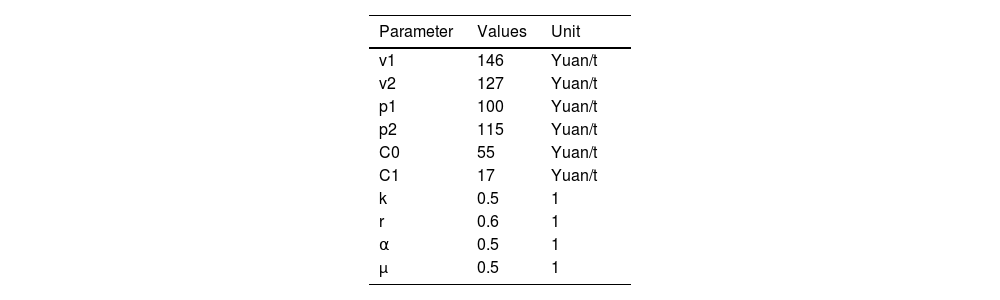

Based on the problem description, the parameters (Table 2) and underlying assumptions are defined as follows:

Parameter settings and related meanings.

| Parameter | Meaning of parameters | Source |

|---|---|---|

| v1 | The valuation of consumers who purchase green innovative products for their products;The valuation of traditional building materials products by consumers who do not purchase green innovative products | (Wang et al., 2025b) |

| v2 | The valuation of traditional building materials products by consumers who purchase green innovative products;The valuation of green innovative products by consumers who do not buy green innovative products(v1>v2) | (Wang et al., 2025b) |

| k | Consumer green preference level | (Mao et al., 2023) |

| r | BMMs unsalable loss coefficient | (Holweg et al., 2016) |

| α | The degree of consumer innovation resistance | (Sun et al., 2022; Heidenreich et al., 2022) |

| L | Profit increase or decrease due to consumer innovation resistance | (Sun et al., 2022) |

| pi | The price of traditional building materials products; the price of green innovative products | (He et al., 2023) |

| C0 | The basic cost of building materials for production units | (Li & He, 2024) |

| C1 | R&D costs of innovative products | (Jiang et al., 2021) |

| μ | The government's subsidy coefficient for BMMs conducting GTI | (Song et al., 2023) |

Assumption 1 A BMM in the market can choose GTI for CDW recycling. If enterprises adopt this technology, the renewable portion of CDW can be transformed into remanufactured products, which are defined as green innovative products. In contrast, products that do not use this technology are regarded as traditional building materials.

Assumption 2 In the CDW market, while consumers are shifting their preference toward green technology products, building material manufacturers continue to prioritize traditional product lines, overlooking actual market demand and resulting in the overstock of conventional items. Moreover, excessive investment in green innovation, without sufficient consideration of the market demand for traditional building materials, may also result in a surplus of innovative products. In such cases, BMMs face unsalable risks and corresponding losses, rdenoted by the unsalable loss coefficient (Holweg et al., 2016).

Assumption 3 Because consumers exhibit varying degrees of resistance toward green innovative products, this study uses α to represent the degree of consumer innovation resistance. Nevertheless, some consumers display positive attitudes toward green product functionality, possess green purchase preferences (He et al., 2019), and gain additional utility from such products (Xie & Guan, 2024). Consumer green preferences are modeled as a function of BMMs’ GTI R&D costs and represented by k, the consumer green preference coefficient.

Assumption 4 Owing to the coexistence of non-innovation resistance and green preference characteristics, consumers who prefer green innovative products value them more highly than traditional building materials do. In contrast, consumers with innovation resistance are reluctant to buy green innovative products, resulting in lower valuations than traditional materials (Xie & Guan, 2024). Among these consumers, those with stronger preferences demonstrate a greater willingness to pay premium prices, meaning they are prepared to bear additional costs. (Yang et al., 2023).

Assumption 5 The unit price of traditional building materials is assumed to be p1, and the price of innovative products is p2. BMMs need to pay a certain R&D cost C1 for GTI. To encourage GTI adoption, the government provides certain subsidies to BMMs when they carry out GTI, and the subsidy coefficient is μ (Song et al., 2023).

Assumption 6 Given that consumers have varying purchasing attitudes toward innovative products, the probability of purchasing green innovative products in the market is x, whereas the probability of not purchasing is (1−x) (Geng et al., 2022). Correspondingly, enterprises may also choose not to adopt GTI and instead produce traditional building materials by existing technologies. The probability of BMMs adopting GTI is assumed to be y, and the probability of non-innovation is (1−y).

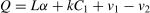

On the basis of these assumptions, this study constructs a payoff matrix for BMMs and consumers under different strategic choices (Table 3). In this game framework, the utility function is expressed as a profit function, where consumer profit corresponds to consumer surplus.

In Table 3, R11 and M11 denote the profits of BMMs’ GTI and the profits of consumers when purchasing green innovative products, respectively; M12 and R12 represent the profits of non-innovative BMMs and consumers purchasing green innovative products, respectively; M21 and R21 correspond to the profits of BMMs’ adopting GTI and consumers not purchasing green products, respectively; and M22 and R22 indicate the profits of non-innovative BMMs and consumers not purchasing green products, respectively.

Calculation of the stable pointThe payoff matrix shows that the expected returns of consumers and BMMs under different strategies are shown in (1), (2), (3), and (4).

The resulting replication dynamic equations are shown in (5) and (6).

Letting F(x)=0 and F(y)=0, five evolutionary stable strategies are identified, namely, (0,0), (1,0), (0,1), (1,1), and (x*,y*). Among them, x* and y* are shown in (7) and (8).

Evolutionary equilibrium stability analysisUsing Friedman’s (1998) proposed analytical approach, this study examines the evolutionary game's equilibrium stability. The Jacobi matrix J is shown in Formula (9).

K11, K12, K21 and K22 are expressed as (10), (11), (12), and (13), respectively.From det(J)>0 and tr(J)>0, the equilibrium point of the replicator dynamic equation satisfying this condition represents the system's evolutionary stable point.

Among them, H, Q, T, and N are specifically expressed as (14), (15), (16), and (17).

In Table 4, a11 and a22 at this point (x*,y*) are both 0, which does not meet the required condition; therefore, this point is not an evolutionary stable strategies (ESS). The stability conditions of the remaining four points (0,0), (1,0), (0,1), and (1,1) are analyzed next.

According to Assumption 4, v1>v2>p2>p1, H<0 and Q>0 can be inferred. On this basis, the stability conditions for the four equilibrium points are derived as follows:

Case 1: When T<0 and N>0, the ESS points are (0,0) and (1,1). In this case, consumers and BMMs form interdependent strategies in the market, with each side’s decision influencing the other. When consumers resist purchasing green innovative products, R&D expenses for such products increase while profit margins shrink, discouraging BMMs from pursuing GTI. Consequently, both parties’ strategies align as non-purchase and non-innovation. Conversely, when consumers show no resistance and display green preferences, the government’s subsidies encourage BMMs to invest in GTI. As profits from green innovative products increase and investment risks decrease, BMMs adopt the GTI strategy, resulting in purchase and innovation as the joint equilibrium.

Case 2: When T<0 and N<0, the ESS is (0,0). In this case, regardless of consumer resistance, the benefits of GTI for BMMs remain low, and government subsidies cannot offset their development losses. Consequently, BMMs do not adopt the GTI strategy. Moreover, consumers’ green preferences influence their degree of innovation resistance and thus alter their profit expectations, reflected in consumer surplus. A higher consumer surplus increases the acceptance of green innovative products, whereas a lower surplus leads consumers to favor traditional building materials. At this point, regardless of whether building material manufacturers adopt GTI, the revenue increase generated by consumer green preferences remains insufficient to offset the loss in consumer surplus caused by innovation resistance. Thus, consumers still opt to accept green innovation products.

Case 3: When T>0N>0, the ESS is (1,1). In this case, government subsidies significantly strengthen GTI adoption by BMMs and increase their innovation profit. Furthermore, the additional income from consumers’ green preferences offsets the decline in consumer surplus caused by innovation resistance, allowing consumers to gain greater utility from purchasing green innovative products. Consequently, consumers prefer green innovative products, and BMMs choose GTI.

ESS analysis indicates that the GTI behavior of BMMs is influenced by consumers’ attitudes toward green innovative products. To further examine the dynamic evolutionary interaction between consumers and BMMs, this study employs MATLAB 2020b to simulate and analyze key influencing factors.

On the basis of a literature review (Reach Construction Consulting, 2025; Glodon, 2025; China Cement Network, 2024; Si et al., 2024; Li & He, 2024) and expert interviews, the initial parameters are set as shown in Table 5. To enhance scientific rigor and objectivity, the selected experts represent leading building-material remanufacturing enterprises within China’s CDW industry.

This section examines the different initial willingness ratios of consumers to purchase green innovative products, denoted as x, and of BMMs to adopt GTI, denoted as y.

The assigned values are 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 0.7, and 0.9, whereas all other parameters remain constant throughout the study.

Fig. 2(a) illustrates that when x = 0.1, 0.3, and 0.5, the evolution trajectory converges toward 0, indicating that the BMMs do not adopt GTI, and the convergence rate decreases as x increases. However, when x increases to 0.7 and 0.9, the trajectory approaches 1, showing that BMMs shift from non-adoption to adoption, with an accelerated rate of GTI uptake. Thus, a greater initial willingness to purchase green innovative products enhances BMMs’ likelihood of adopting GTI.

Influence of initial willingness on system evolution (a) Effect of consumers’ initial willingness to purchase green innovative products on BMMs’ adoption of GTI. (b) Effect of BMMs’ initial willingness to adopt GTI on consumers’ purchase of green innovative products.

Note: In Fig. 2(a), x denotes consumers’ initial willingness to purchase green innovative products. The horizontal axis represents evolution time, and the vertical axis represents y, the BMMs willingness to adopt GTI. willingness. When time = 0, y = 0.5. As time progresses, higher x values correspond to stronger BMMs’ willingness to adopt GTI. In Fig. 2(b), y represents the initial willingness of BMMs to adopt GTI. The horizontal axis indicates evolution time, and the vertical axis indicates x, the consumers’ willingness to purchase green innovative products. When time = 0, x = 0.5. Compared with (a), y = 0.5, a peak appears around time = 0.06-0.07. A higher y value indicates stronger consumer willingness to purchase green innovative products.

Fig. 2(b) shows that as y increases, the evolution trend and convergence rate resemble those in Fig. 2(a). Specifically, when y = 0.1, 0.3, and 0.5, consumers resist innovation and prefer traditional building materials, whereas at y = 0.7 or higher, they gradually become willing to purchase green innovative products. This finding suggests that changes in BMMs’ GTI behavior influence consumer attitudes toward innovation, prompting a shift from non-purchase to purchase of green products. Therefore, consumers’ willingness to purchase green innovative products and BMMs’ willingness to adopt GTI exhibit a two-way feedback mechanism.

In addition, it is worth noting that when x = 0.5 in Fig. 2(a), the evolution trajectory does not exhibit a continuous downward trend over time but initially decelerates before accelerating. In Fig. 2(b), when y = 0.5, the trajectory displays a brief rise followed by a rapid decline. This pattern indicates that when both initial willingness levels are 0.5, the evolutionary trends of consumers and BMMs shift from smooth to fluctuating behavior.

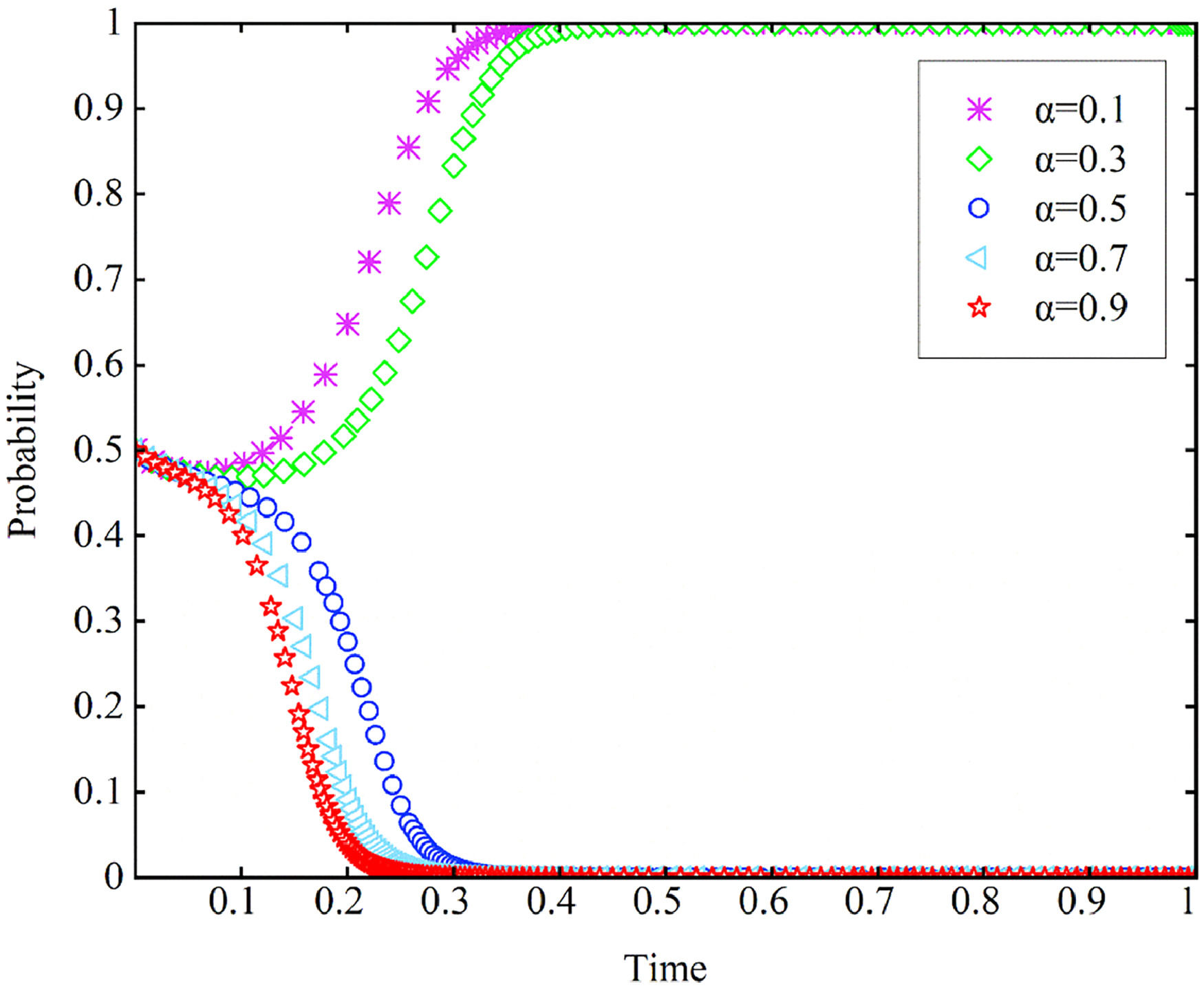

Sensitivity analysisInfluence of the degree of consumer innovation resistanceAs shown in Fig. 3, as the degree of innovation resistance (α) increases from 0.1 to 0.9, the BMMs’ strategy shifts from adopting GTI to non-adoption. When α is small (0.1, 0.3), the evolutionary trajectory of BMMs converges toward 1 and remains stable, indicating the sustained adoption of GTI. The rate of this tendency α decreases gradually as α increases. However, when α is large (0.5, 0.7, 0.9), the trajectory changes direction and stabilizes at 0, indicating non-adoption of GTI. The convergence rate in this case is opposite to that observed when α is small.

Influence of the degree of consumer innovation resistance on BMMs’ strategic evolution paths and outcomes.

Note: In the figure, α represents the degree of consumer innovation resistance. The horizontal axis denotes evolution time, and the vertical axis indicates BMMs’ willingness to adopt GTI(y). When time = 0, y = 0.5. As α changes, the y value becomes polarized. A larger α(≥0.5) corresponds to lower BMMs’ willingness to adopt GTI.

Fig. 4 shows that the evolutionary trajectory of BMMs gradually stabilizes at 1 as the consumer green preference level k increases from 0.1 to 0.9. Moreover, greater k values accelerate the evolutionary process. This finding indicates that changes in consumer green preference do not alter BMMs’ final strategy choice but affect the rate of adoption—higher k values lead to faster GTI adoption among BMMs.

The effect of consumer green preference levels on BMMs' Strategy Evolution Paths and Outcomes.

Note: In the figure, k denotes the level of consumer green preference. The horizontal axis represents evolution time, and the vertical axis represents BMMs’ willingness to adopt GTI(y). When time = 0, y = 0.5. A higher k corresponds to a faster increase in BMMs’ willingness to adopt GTI.

The simulation results show that the initial willingness of consumers to purchase green innovative products and BMMs’ willingness to adopt GTI exert different effects on the strategic decisions of both parties. At certain values, the strategic behaviors of both sides exhibit fluctuations.

Initially, consumers exhibit low willingness to purchase green innovative products(x≤0.5), and BMMs face little external pressure to pursue technological upgrades, resulting in market inertia. This occurs because GTI models typically require substantial R&D investment, and firms fear that limited consumer demand may fail to generate adequate returns, dampening their early motivation to innovate. However, as x exceeds 0.5, consumers’ recognition of green product performance strengthens, and market demand for GTI products becomes more robust, prompting BMMs to adopt innovation more actively and accelerating progress. Furthermore, as the penetration of green innovation products in the CDW market increases, consumer behavior gradually shifts from initial resistance to active acceptance. Interestingly, when both parties’ initial willingness reaches 0.5, BMMs and consumers display temporary caution or hesitation—a condition that dissipates over time. This may be due to random market factors such as consumer green preferences, the market share of traditional versus innovative products, and competitive dynamics, which cause fluctuations in BMM adoption decisions. BMMs remain uncertain about consumer purchasing intentions and cannot accurately predict CDW market trends, leading to a conservative approach. Similarly, limited promotion of GTI by building materials manufacturers reduces consumer awareness of product characteristics, temporarily heightening resistance.

Building on the discussion of consumer purchasing intentions and BMMs’ willingness to adopt innovation, the technological advancement and mutual benefits of the green building materials market can be realized only when consumers purchase innovative green products and manufacturers maintain strong innovation intent. For manufacturers, achieving product differentiation through GTI allows them to capture market demand and secure a first-mover advantage. This finding aligns with that of Khan et al. (2022), who demonstrated that reducing consumer resistance to green innovative products significantly enhances GTI practices among SMEs. Moreover, unlike traditional economic models employing quantitative approaches to analyze GTI, this study applies an evolutionary game framework to uncover the dynamic evolution of corporate GTI behavior, offering new methodological tools for advancing research in this domain. However, because of differences in theoretical foundations, the findings concerning consumer resistance and its negative influence on manufacturers’ GTI behavior diverge from those of Guo et al. (2023). Drawing on RDEU theory, they developed a model showing that manufacturers may still engage in GTI even when consumers exhibit strong resistance. This divergence likely arises because our study integrates IRT with consumer characteristics, emphasizing the incorporation of IRT into consumer purchase behavior relationships rather than contextual variations. Moreover, existing research suggests that disruptions caused by adverse random factors can lead manufacturers to hesitate in innovation decisions (Xu & Tan, 2025), potentially triggering “free-rider” behavior (consumers waiting for others to try first) or “herd effects” (firms responding to others’ decisions) within the supply chain (Raafat et al., 2009). These phenomena, which are consistent with the divergent initial willingness results explored here, underscore the crucial role of innovation resistance in shaping purchasing intention and provide a scientifically grounded dynamic evolutionary perspective for future research.

The degree of consumer innovation resistanceFig. 3 simulations indicate that the degree of consumer innovation resistance not only has a heterogeneous effect on BMMs’ GTI strategy choices but also causes notable shifts in their strategic behavior.

When consumer innovation resistance decreases, BMMs mitigate innovation risk, actively pursue technological innovation to gain market advantages, and adopt innovative strategies to advance their interests. Conversely, greater consumer innovation resistance leads consumers to reject green innovative products, prompting BMMs to forgo GTI to prevent profit losses from reduced product acceptance. Therefore, enhancing BMMs’ willingness to adopt new technologies requires improving consumers’ psychological acceptance of innovation.

Ye et al. (2024) provide empirical support for this conclusion, emphasizing that consumer resistance reduces the market share of innovative products and negatively influences firms’ innovation strategies. Similarly, Ruetgers et al. (2025) reported that increasing consumer acceptance of innovative business models encourages manufacturers to adopt them, explaining why lower consumer innovation resistance increases the likelihood of BMMs engaging in GTI behavior. However, Kesidou & Demirel (2012) hold a contrasting view, arguing that changes in consumer demand for green innovation do not necessarily stimulate greater corporate investment in innovation. This divergence likely arises from differences in research domains and methodologies. Specifically, although Kesidou and Demirel’s analysis of consumer influence on corporate eco-innovation spans multiple sectors (e.g., pollution prevention and green product design), it overlooks the unique features of the building materials industry, thereby limiting model accuracy. Moreover, the evolutionary game approach adopted here is more suitable than the traditional static Heckman model for examining the dynamic environmental challenges that consumers face in the CDW context. Consequently, this framework provides CDW-specific insights into corporate GTI behavior, enhancing the practical applicability of IRT.

Consumer green preference levelAs illustrated in Fig. 4, the level of consumer green preference accelerates BMMs’ adoption of GTI behaviors, although it does not alter their fundamental strategic choices. The promotional effect on GTI adoption strengthens as consumer green preferences intensify.

In the short term, consumer innovation resistance and green preferences may counterbalance one another. Nevertheless, green preferences can mitigate consumer resistance, offset BMMs’ innovation risk, and thus promote GTI adoption. Over time, manufacturers initially struggle to attract consumers due to persistent skepticism toward innovative products. However, this hesitation diminishes as consumer green preferences increase. In the CDW market, stronger green preferences heighten product expectations and expand consumer surplus. This positive feedback mechanism subtly enhances the profitability and competitiveness of BMMs, thereby accelerating their GTI engagement. Hence, cultivating consumer green preferences is crucial for enterprises seeking to advance GTI behavior.

However, this finding contrasts with the outcomes of Xing et al. (2020). Their results indicate that as consumers increasingly favor low-carbon products, manufacturers’ expected returns decline, thereby weakening their incentive to pursue innovation. This discrepancy stems from their incorporation of competition levels among third-party recyclers. This dynamic partly obscures the direct interaction between consumers and manufacturers. Conversely, this study provides a clearer depiction of how consumer green preferences influence firms’ GTI behavior. Moreover, our emphasis on “the critical role of consumer green preference in driving corporate GTI behavior” aligns with the findings of Zhou et al. (2025). Similarly, they contend that heightened green preferences expand the demand for eco-friendly products, encouraging firms to adopt GTI strategies to capture market share and increase profitability. Hence, this study contributes industry-specific insights from the building materials sector to the broader literature on consumer green preferences and corporate GTI.

Conclusion and implicationsConclusionDrawing on consumer IRT, this study constructs an evolutionary game model involving BMMs and consumers to explore how consumer purchasing psychology and BMMs’ GTI behavior evolve under varying conditions. The main conclusions are summarized as follows:

The varying initial willingness of consumers to purchase green innovative products and of BMMs to adopt GTI influences the strategic decisions of both parties and can produce fluctuations at specific critical points. When both sides’ initial willingness exceeds 0.5, consumers and BMMs tend to adopt strategies that favor GTI and the purchase of green products. Conversely, when willingness is below this threshold, their strategies are more likely to settle into a negative equilibrium characterized by resistance and non-purchase. Importantly, at the critical threshold of 0.5, information asymmetry and innovation resistance may trigger free-riding and herd effects.

There is heterogeneity in how the degree of consumer innovation resistance influences BMMs’ GTI strategy decisions. A higher degree of innovation resistance (x≥0.5) negatively affects BMMs’ willingness to adopt GTI, whereas lower resistance levels encourage adoption and strengthen innovation (x<0.5) motivation.

Although consumer green preferences do not alter manufacturers’ ultimate GTI strategy choices, they affect the rate of convergence. Specifically, higher levels of consumer green preference mitigate the decline in consumer surplus caused by innovation resistance, thereby accelerating BMMs’ engagement in GTI behavior.

Management implicationsDrawing on the above conclusions, this study provides the following targeted recommendations for BMMs and consumers.

(1) BMMs. BMMs should develop innovation strategies on the basis of both market realities and consumer behavior, ensuring that their technological choices align with consumer demand and long-term sustainability objectives.

First, BMMs should move beyond traditional environmental models by introducing transparent and accessible incentive policies to sustain consumer engagement. For example, establishing green consumption incentive mechanisms such as product feedback rewards can effectively encourage long-term participation. On the one hand, implementing a “waste building material recycling and exchange” system allows companies to launch “trade-in” programs or recycling point schemes. Consumers can accumulate points by returning waste materials (e.g., old tiles, scrap joists) to redeem discounts on new products or property-related services such as home maintenance visits. This approach not only enhances consumer participation but also supports the production and circulation of recycled goods. On the other hand, “green consumption vouchers” can be distributed within specific CDW markets or retail channels. Building material companies may collaborate with governments and retailers to provide targeted subsidies for green innovative products, thereby reducing purchasing barriers and strengthening consumers’ willingness to buy green products. Notable examples include China’s Meixin Group’s “trade-in” initiative (Sichuan Economic Daily, 2025) and the UK’s Pallet LOOP program (Wood & Panel, 2024), both of which use direct economic incentives and subsidies to increase recycling engagement while lowering production costs for recycled BMMs.

Second, BMMs should integrate product promotion with incentive models. They should consistently highlight the functionality and environmental benefits of green innovative products to build a positive brand image and strengthen consumers’ green preferences. In doing so, building material companies must avoid subjective bias, limit excessive technical detail, and design promotions that align with consumers’ lifestyles and innovative needs. For example, firms can use short videos, live demonstrations, and product experience events to visually present the performance advantages and environmental value of recycled products, reducing consumer skepticism. A notable example is GELAISI, which launched consumer-oriented slogans such as “Affordable Home Makeovers, Hassle-Free Delivery.” The company utilized Douyin (TikTok) short videos for promotion and paired them with authentic product experiences and services as part of its campaign (Jiuzheng Building Materials Network, 2025).

Third, alongside product promotion and incentive systems, manufacturers’ technological breakthroughs remain equally vital. BMMs should establish digital user feedback and data-driven production systems. By developing proprietary WeChat mini-programs or integrating them with industrial internet platforms (e.g., ERP or blockchain), they can monitor CDW green product market share, price sensitivity, and consumer feedback in real time. For example, a “scan-to-feedback-earn-points” feature within a mini-program can allow consumers to upload product photos and reviews in exchange for a 10-yuan discount coupon, effectively combining incentive mechanisms with active user participation. When fluctuations in purchasing intent are detected, building material companies should promptly adjust production plans and progressively expand GTI product supply to prevent free-riding behavior. A notable case is Oriental Yuhong’s “Rainbow Eye” AI data dashboard, which monitors recycled building material sales dynamics across regional markets in real time. Combined with solid-waste resource utilization technology, this system enhances cost efficiency, accelerates pricing responsiveness, and strengthens overall market competitiveness (China City Network, 2025).

Fourth, BMMs with strong comprehensive capabilities should actively align with government policies on industrial upgrading and green transformation by launching small-scale pilot projects for recycled products in regions with high green preferences. Pilot enterprises should systematically record sales performance and profitability data for recycled products. On the basis of monthly and annual financial analyses, they should optimize product portfolio strategies that balance consumer green demand with the economic interests of building material enterprises. For example, during its recycled aggregate concrete pilot project in the Shanghai Free Trade Zone, China Shanghai Construction Group regularly published environmental and economic comparison data, including carbon reduction assessment reports (Shanghai Construction Group, 2024). By leveraging a construction cloud platform to disseminate pilot results, the company effectively enhanced its trust in recycled materials across the entire supply chain.

(2) Consumers. Within the complex product market, consumer perceptions of CDW remanufactured products remain diverse. To address these challenges, consumers should enhance their understanding of CDW recycled products and actively purchase GTI products, thereby fostering mutual benefits between consumers and manufacturers. First, consumers should cultivate sustainable consumption habits, carefully assess the quality of recycled products, and provide timely feedback. They can use enterprise mini-programs (via QR codes), after-sales hotlines, or other service channels to inquire about product origins, share usage experiences, and offer improvement suggestions. Second, consumers should actively participate in trade-in and recycling initiatives. For instance, when new recycled products are purchased, they can proactively ask brand retailers whether old material recycling services are available. Finally, consumers with strong green preferences can share their experiences with recycled products and building material brands through online forums or social media, encouraging broader public engagement in sustainable consumption practices.

This study seeks to promote the development of green technologies among BMMs by establishing a virtuous cycle of green production and consumption.

Limitations and future workThis study has several limitations. First, the model design relies on simplifying assumptions, such as binary strategy choices, a fixed government subsidy rate, and homogeneous consumer behavior. Future research could incorporate multiple strategy options, dynamic subsidy mechanisms, or heterogeneous consumers to improve the model’s realism and explanatory power. Additionally, in practice, BMMs’ adoption of GTI is shaped not only by consumer behavior but also by the innovation activities of other stakeholders, including CDW recycling firms, distributors, and industry competitors. Future studies could therefore construct multi-agent game models involving recyclers or retailers to examine how multistakeholder interactions affect GTI behavior or employ empirical validation to test and refine the model’s predictions.

CRediT authorship contribution statementXingwei Li: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Guichuan Zhou: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Software, Formal analysis, Data curation. Beiyu Yi: Writing – review & editing.

The authors declare that they have no financial and personal relationships with other people or organizations that can inappropriately influence our work, there is no professional or other personal interest of any nature or kind in any product.

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 72204178), Sichuan Science and Technology Program, and Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan, China (grant number 2023NSFSC1053). We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Chuyue Zhou from the College of Architecture and Urban–Rural Planning at Sichuan Agricultural University for providing valuable technical advice on variable selection.