In the U.S., sepsis afflicts 1.7 million adults, causing 270,000 deaths each year. Early detection of sepsis could decrease the number of deaths by 92,000 annually and decrease hospital expenditures by 1.5 billion USD. Few prior studies and reviews have presented a holistic understanding of the relationship between machine learning and existing process improvement measures. This study, in addition to discussing machine learning and existing process improvements measures, elaborates on the disadvantages and the barriers to integrating machine learning into the clinic. This article synthesizes previous studies to educate healthcare professionals on effectively managing sepsis by leveraging the benefits of machine learning.

MethodsThis study used the PubMed database. Search terms include sepsis antibiotics, sepsis process improvement, sepsis machine learning. Our search criteria included previous studies published between January 1, 2017, and February 1, 2022.

Results/discussionAlthough machine learning algorithms have better predictive capabilities, their effectiveness in the clinical setting is limited as studies show mixed results because the medical staff often fails to intervene. To overcome poor interventional response, clinicians need to work with the facility's IT department to ensure integration into clinical workflow and minimize alert-fatigue. Algorithms should enhance the productivity of clinical teams, not attempt to replace them entirely.

ConclusionHospitals can employ process improvement measures that effectively utilize machine learning algorithms to ensure integration into clinical workflows. Healthcare professionals can utilize workflow tools in addition to the predictive capabilities of machine learning to enhance clinical decisions in sepsis.

Pocos estudios y revisiones anteriores han presentado una comprensión holística de la relación entre el aprendizaje automático y las medidas de mejora de procesos existentes. Este estudio, además de discutir el aprendizaje automático y las medidas de mejora de procesos existentes, profundiza en las desventajas y las barreras para integrar el aprendizaje automático en la clínica. Este artículo sintetiza estudios previos para educar a los profesionales de la salud sobre el manejo efectivo de la sepsis aprovechando los beneficios del aprendizaje automático.

MétodosNuestro estudio utilizó la base de datos PubMed. Los términos de búsqueda incluyen antibióticos para sepsis, mejora de procesos para sepsis, aprendizaje automático para sepsis.

Resultados/discusiónAunque los algoritmos de aprendizaje automático tienen mejores capacidades predictivas, su efectividad en el entorno clínico es limitada ya que los estudios muestran resultados mixtos porque el personal médico a menudo no interviene. Para superar una respuesta intervencionista deficiente, los médicos deben trabajar con el departamento de TI de la instalación para garantizar la integración en el flujo de trabajo clínico y minimizar la fatiga por alertas. Los algoritmos deben mejorar la productividad de los equipos clínicos, no intentar reemplazarlos por completo.

ConclusiónLos hospitales pueden emplear medidas de mejora de procesos que utilizan de manera efectiva algoritmos de aprendizaje automático para garantizar la integración en los flujos de trabajo clínicos. Los profesionales de la salud pueden utilizar herramientas de flujo de trabajo además de las capacidades predictivas del aprendizaje automático para mejorar las decisiones clínicas en sepsis.

Sepsis is characterized as an overactive inflammatory response by the host's immune system to an infection that can lead to multiple organ failures and death.1 In the U.S., sepsis afflicts 1.7 million adults, causing 270,000 deaths each year.2–4 Sepsis is implicated in approximately 30–50% of all hospital deaths,4 with yearly expenditures reaching $24 billion1 in the U.S. Early detection of sepsis could decrease the number of deaths by 92,000 annually and decrease hospital expenditures by 1.5 billion USD.5 Due to the high burden of disease, more research is needed to raise awareness for improving sepsis management.6

Previous research has explored improvements in sepsis management. Studies have focused on a specific area, such as the relationship between the timing of antibiotics and sepsis, implementation of standardized protocols, or the role of machine learning in sepsis detection. Few prior studies and reviews have presented a holistic understanding of the relationship between machine learning and existing process improvement measures.

This study, in addition to discussing machine learning and existing process improvements measures, elaborates on the disadvantages and the barriers to integrating machine learning into the clinic. This narrative review synthesizes previous studies to educate healthcare professionals on effectively managing sepsis by leveraging the benefits of machine learning. This study will educate healthcare professionals to improve compliance with quality measures created by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).7

MethodsSearch criteriaThis study used the PubMed database. Search terms include sepsis antibiotics, sepsis process improvement, sepsis machine learning. Our search criteria included previous studies published between January 1, 2017, and February 1, 2022. Additional articles were identified through manual searches in the references of articles found in the initial PubMed search. Articles that did not have the published text in English were excluded. Articles were excluded if they were too focused on a particular demographic (e.g. pediatric ICU), focused on quality improvement metrics with minimal clinical impact or discussion, or summarized previous studies without adding meaningful comparisons or discussion. Articles were also excluded if they did not focus on improvements or deteriorations in sepsis detection. References of high-impact studies were included if they provided substantial contribution to the study and helped supplement discussion.

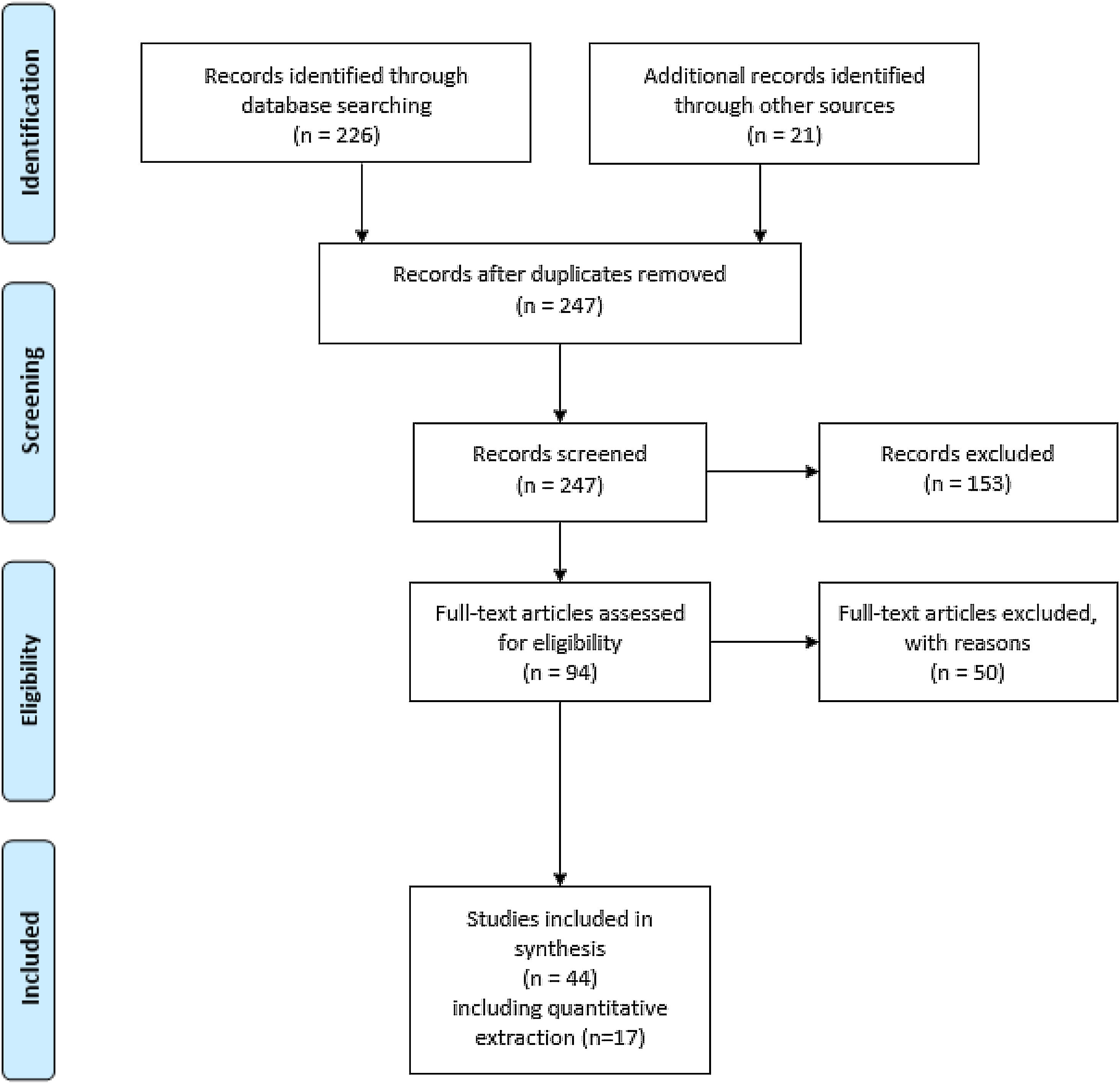

Fig. 1 shows the flow diagram for this search. Quantitative data was extracted from 17 studies, including outcomes, area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC), and time to antibiotic administration.

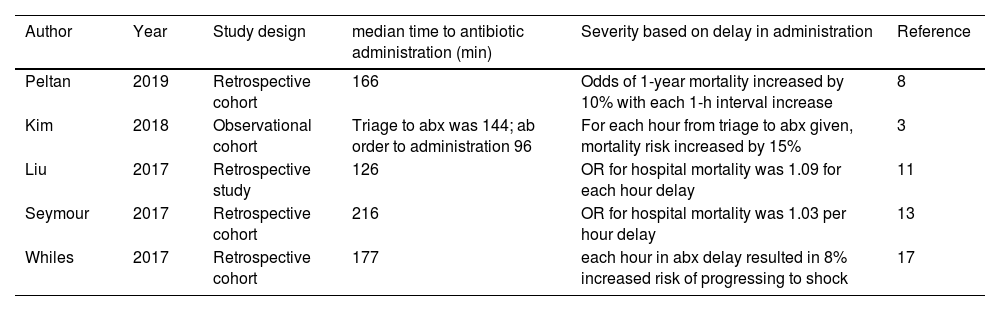

Results/discussionEarly antibiotic administration in the prevention of sepsisDespite the high burden of disease associated with sepsis,1–4 many sepsis-associated deaths are preventable. One in 8 sepsis-associated deaths were deemed preventable.4 Preventable sepsis deaths were caused by delays in recognition, antibiotic administration, and source control. Process improvement measures aim to decrease these preventable deaths by reducing the delay between recognition and antibiotic administration.4 Numerous studies have emphasized that the appropriate timing of antibiotics plays an integral role in preventing sepsis-associated deaths or subsequent morbidities.3,8–14 Except for previous studies conducted with a small sample size,15 recently published studies8,11,13,16,17 (see Table 1) found a positive association between delay in antibiotic administration and sepsis-associated deaths.

Summary of studies showing relationship between antibiotic administration and mortality associated with sepsis.

| Author | Year | Study design | median time to antibiotic administration (min) | Severity based on delay in administration | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peltan | 2019 | Retrospective cohort | 166 | Odds of 1-year mortality increased by 10% with each 1-h interval increase | 8 |

| Kim | 2018 | Observational cohort | Triage to abx was 144; ab order to administration 96 | For each hour from triage to abx given, mortality risk increased by 15% | 3 |

| Liu | 2017 | Retrospective study | 126 | OR for hospital mortality was 1.09 for each hour delay | 11 |

| Seymour | 2017 | Retrospective cohort | 216 | OR for hospital mortality was 1.03 per hour delay | 13 |

| Whiles | 2017 | Retrospective cohort | 177 | each hour in abx delay resulted in 8% increased risk of progressing to shock | 17 |

Previous studies underscore the importance of early antibiotic administration in improving clinical outcomes. A retrospective cohort study8 examining 10,811 emergency room patient encounters found that the mean door-to-antibiotic time was 166min and the 1-year mortality was 19%. Odds of 1-year mortality increased by 10% with each 1-h interval increase in door-to-antibiotic time. Delays in antibiotics have long-lasting effects on mortality; patients who survived 30 days with a delay in antibiotics still had an increased risk of mortality.8 A retrospective study with 48,934 hospital encounters found that the risk of mortality (OR – 1.03 per hour) increased for each hour of delay in antibiotic administration.13 An observational study3 conducted on 117 patients determined that for each hour delay in antibiotics ordered following triage, the mortality risk increased by 22%; for each hour delay in administering antibiotics following triage, the mortality risk increased by 15%. Furthermore, a retrospective study11 stratifying 35,000 patients based on the severity of sepsis (i.e. sepsis, severe sepsis, and septic shock) found that each hour delay increased the risk of absolute mortality, with odds of mortality increasing the most in the severe group – septic shock. After gathering the appropriate amount of data, quality improvement measures to improve detection of sepsis can facilitate timely administration of antibiotics and reduce sepsis-associated deaths.9,13

However, others have recommended a more nuanced approach to antibiotic administration in sepsis. While delaying antibiotics can increase the risk of mortality, an aggressive antibiotic treatment course can result in C. difficile infection, acute kidney injury, etc.9 Consequently, the administration of antibiotics should correlate with the severity and probability of sepsis for each patient. Management can be improved with technologies, such as machine learning, that enhance accuracy in diagnosis given the varied presentation of sepsis.9

Sepsis process improvementsAs part of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign, hospitals have adopted guidelines and checklists to improve sepsis management.18 Many studies16,19–21 implemented a multidisciplinary approach and process improvement measures, such as flagging, monitored bed allocation, checklist protocols, and education campaigns. Many process improvement measures have translated to better outcomes, including increased early detection of sepsis, leading to improved 30-day survival, and cost savings stemming from decreased length of stay (LOS).16,19–21 The paper-based protocol checklist – Emergency Room Nurse Sepsis Identification Tool (ERNSIT)5 – led to significant improvements in average bundle compliance time in sepsis mortality (decreased by 5.9%), and antibiotic administration. Nurse protocols have improved the collection of lactate and antibiotic administration compared to baseline.5,21,22 3-h sepsis bundle compliance metrics increased from 30% to 80%.21

However, existing process improvement measures do not always yield improvements in clinical outcomes and are often associated with increased costs. A prospective cluster trial23 analyzing multidisciplinary process improvements (quality improvement teams, audit, feedback, educational outreach, and reminders) found that the differences in mortality rate and time to antibiotic therapy between groups could not be attributed to a multifaceted intervention campaign, echoing the results of a study24 published in 2015. Additionally, many studies on sepsis improvement indicate that education is needed to maintain change, which adds additional cost to the hospital.5,19,22,23,25

Machine learning in sepsis detectionThe COVID-19 pandemic increased awareness of informational and communication technologies (ICTs) to leverage databases, platforms, etc. to deliver healthcare.26 Machine learning and algorithms hold great promise in supporting detection of sepsis early as clinicians may misdiagnose sepsis amidst a myriad of underlying conditions.27–29 When compared with traditional process improvement methods, one machine learning algorithm developed at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) showed better predictive capabilities than Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA), Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS) criteria, and Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS), allowing earlier detection of sepsis.30 A randomized control trial30 evaluating the UCSF algorithm connected to the electronic health record (EHR) to predict severe sepsis in 2 ICUs, incorporated multiple inputs (blood pressure, heart rate, temperature, respiratory rate, SpO2, age, posivitive labs, pH, WBC, glucose, etc.). Results showed improved outcomes following implementation: LOS decreased from 15.8 to 9.83 days and the in-hospital mortality rate decreased from 21.3% to 8.96%.30 Other prospective and implementation studies have stratified septic patients classified into low, medium, and high-risk groups, revealing a difference in LOS, 30-day mortality, and 30-day patient admission.31,32

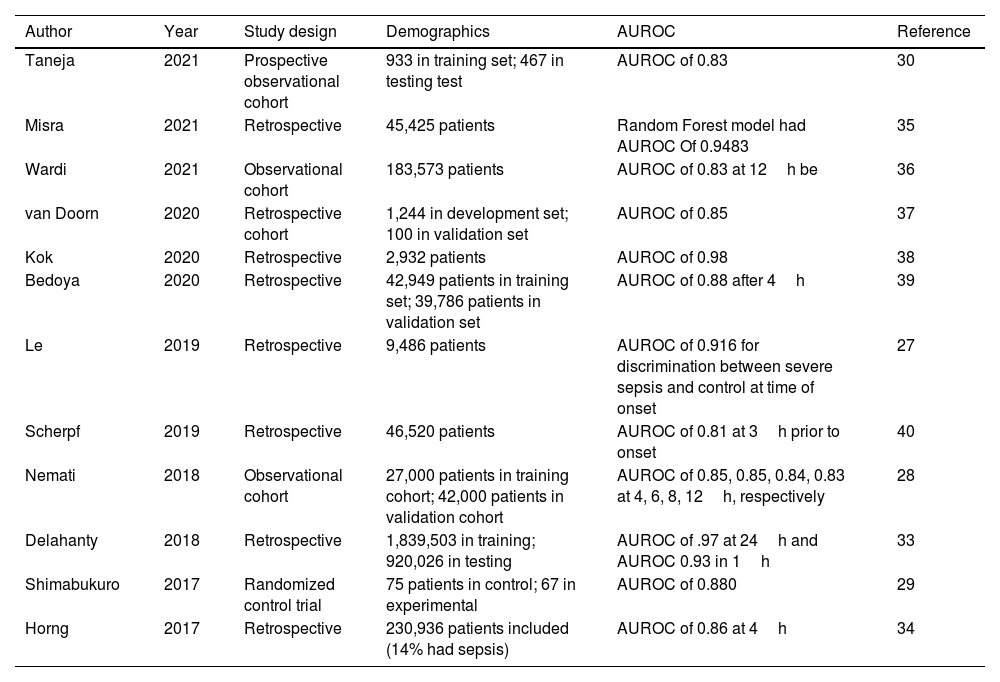

Most of the literature shows that machine learning has focused on retrospective detection of sepsis.33 For sepsis prediction, AUROC ranged from 0.68 to 0.99 in ICU; 0.96 to 0.98 in the hospital; 0.87 to 0.97 in the emergency room.33Table 2 summarizes the AUROC from recent studies.28–31,34–41 Although machine learning can outperform traditional clinical judgment in anticipating sepsis,34,38 more research must be conducted on evaluating interventional performance to improve gaps between sepsis alert notification and clinical response.29,33

Summary of recent studies using machine learning to detect sepsis.

| Author | Year | Study design | Demographics | AUROC | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taneja | 2021 | Prospective observational cohort | 933 in training set; 467 in testing test | AUROC of 0.83 | 30 |

| Misra | 2021 | Retrospective | 45,425 patients | Random Forest model had AUROC Of 0.9483 | 35 |

| Wardi | 2021 | Observational cohort | 183,573 patients | AUROC of 0.83 at 12h be | 36 |

| van Doorn | 2020 | Retrospective cohort | 1,244 in development set; 100 in validation set | AUROC of 0.85 | 37 |

| Kok | 2020 | Retrospective | 2,932 patients | AUROC of 0.98 | 38 |

| Bedoya | 2020 | Retrospective | 42,949 patients in training set; 39,786 patients in validation set | AUROC of 0.88 after 4h | 39 |

| Le | 2019 | Retrospective | 9,486 patients | AUROC of 0.916 for discrimination between severe sepsis and control at time of onset | 27 |

| Scherpf | 2019 | Retrospective | 46,520 patients | AUROC of 0.81 at 3h prior to onset | 40 |

| Nemati | 2018 | Observational cohort | 27,000 patients in training cohort; 42,000 patients in validation cohort | AUROC of 0.85, 0.85, 0.84, 0.83 at 4, 6, 8, 12h, respectively | 28 |

| Delahanty | 2018 | Retrospective | 1,839,503 in training; 920,026 in testing | AUROC of .97 at 24h and AUROC 0.93 in 1h | 33 |

| Shimabukuro | 2017 | Randomized control trial | 75 patients in control; 67 in experimental | AUROC of 0.880 | 29 |

| Horng | 2017 | Retrospective | 230,936 patients included (14% had sepsis) | AUROC of 0.86 at 4h | 34 |

Although machine learning algorithms can accurately predict sepsis, their effectiveness in the clinical setting is limited with studies showing mixed results.25,42–44 Some artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms are not programmed to detect all clinically relevant features seen by clinicians, and many providers do not always respond to the notifications.42 The University of Pennsylvania Health System deployed the Early Warning System (EWS) 2.0 in acute care hospitals. Despite the accurate prediction of sepsis, EWS 2.0 did not significantly improve clinical outcomes. Although machine learning can detect clinical events much earlier than traditional clinical judgment, the medical staff often fails to intervene (e.g. administer antibiotics). Low levels of intervention could stem from uncertainty on handling patients who have triggered an alert but show no signs of instability.43

This uncertainty and poor impression stems from a lack of interpretability in machine learning platforms.45,46 An observational study on EWS 2.0 implementation revealed that most healthcare providers had poor impressions of alerts and early morning monitoring; only 30% of nurses and 9% of physicians said that the alert system improved management.46 Clinicians were the group that found it least helpful in improving sepsis management. Clinicians may distrust machine learning if its algorithms supersede clinical judgment without proper explanation.46 Future usability necessitates clear communication and transparency between clinicians and developers to achieve buy-in.45 Without adequate explanation and education, clinicians continue to view machine learning platforms as “black box models” with limited clinical use despite high AUROC scores.46

Since usability is critical to the effectiveness of the monitoring systems, clinicians should be able to use the system without much difficulty.44 An add-on EHR may inevitably lead to lower customizability which could compromise optimal performance. Clinicians need to work with the facility's IT department to ensure the product meets clinical expectations.44 Improvements could use machine learning's customizable input features and no fixed set target (unsupervised) to identify patterns to determine patients with a high probability of sepsis.47 However, adjusting and customizing input features for each department might improve precision but conflict with interoperability.44,47

Designing a system to avoid alert fatigueMany providers fail to respond to electronically-based notifications due to alert fatigue.48,49 Instead of remaining with the traditional EHR, hospital systems should adopt a user-centered design (UCD).49 A UCD develops an interface that adapts to clinical practice and improves task efficiency. Intuitive design and human factors help improve user satisfaction and ensure prompt response to alerts. Ruminski et al. found that the rate of sepsis decreased significantly with the display of a visual monitor.50 Color coding and screen position in the user's visual field has also been shown to improve provider satisfaction.49 Studies that use a visual monitor to display predictive analytics reduced the rate of sepsis by more than 50%. Following the implementation of an LCD monitor that continuously displayed predictive analytics, the rate of sepsis in a surgical trauma ICU decreased by more than 50%.50

Clinicians and department end-users should play a significant role in the development of the visual interface.44,47,48 Adjusting and customizing input features for each department might improve precision but conflict with interoperability.47 An add-on EHR may inevitably lead to lower customizability.44 Clinicians need to work with the facility's IT department to ensure the product meets clinical expectations while remaining compatible with the system.44,47

Utilizing machine learning and interfaces to improve sepsis managementAlthough the field of AI shows tremendous benefit in predicting sepsis, solely relying on machine learning usually does not translate to improved outcomes in sepsis management.25,42–44 However, current evidence shows that machine learning capabilities have surpassed the predictive ability of clinical judgment in early identification of sepsis.27–29 Clinicians should aim to achieve a balance between relying solely on machine learning or remaining attached to traditional paper-based systems.

Proper sepsis management should combine streamlined workflow protocols with the predictive capabilities of algorithms. Algorithms should enhance the productivity of clinical teams, and not replace them. Algorithms and electronic interfaces should reinforce clinical decisions and maintain streamlined workflows. Electronic interfaces could improve pain points identified during process improvement. For example, written handoffs between shifts lead to inconsistencies while electronic printouts and displays reduce errors and increase consistency across shift changes.51 After implementation of the electronic handoff tool, accuracy user satisfaction increases, without the need for continued education.51

Change management includes defining protocol, educating staff, creating awareness and excitement.25 Change management can assist in sustaining improvement. Nurses receive real-time notifications from algorithms. Although most studies showed limited improvement in clinical outcomes, an interventional study25 incorporating change management decreased sepsis-associated death by 53% and the 30-day readmission rate decreased by 6%. Change management in sepsis-detection software can standardize handoffs by increasing clarity of responsibility between shifts, improving completeness, and lowering inaccuracies.51

Although the cost to design and implement could be a barrier to implementation in hospitals,44 the burden of disease for sepsis is too high to ignore. As mentioned earlier, in the US, sepsis causes 270,0002 deaths each year, with yearly expenditures reaching $24 billion.1 Since most of these deaths are preventable,4 hospital systems can save the lives of thousands of patients by implementing key changes to sepsis workflow processes.

LimitationsThis study examines content and data from articles in PubMed due to ease of retrievability. Most of the selected articles are retrospective observational studies because few prospective and randomized controlled trials have evaluated the efficacy of machine learning integration. Although the selection contains articles with retrospective and prospective studies, the large proportion of restrospective studies could bias results. This study only includes articles that have a medium that is publishable in English based on the language proficiency of the authors and difficulty acquiring non-English text.

ConclusionOur study brings attention to the high burden of disease in sepsis. A review of recently published studies show that sepsis-associated deaths are largely preventable. Although our study does not present novel findings, it provides a comprehensive review of the emerging trends in sepsis management. The current literature suggests that healthcare providers should aim to achieve a balance between dependency on machine learning algorithms and process improvement measures. Clinicians should utilize predictive analytics to enhance clinical decisions and help maintain sepsis workflow protocols.

The review of the literature helps shed light on a need to develop management systems that effectively detect sepsis while not compromising the clinical response. After evaluating multiple studies, this study also provides suggestions to improve clinical response to predictive alerts. Hospital systems and patient support groups can advocate for greater awareness in preventing sepsis-associated deaths and champion efforts that effectively reduce the associated burden of disease.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant funding from agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approvalIRB approval was not required for this study.

Conflict of interestSarma Velamuri, MD is the co-founder and CEO of Luminare, Inc., a company dedicated to saving patient lives by improving sepsis workflow. Liam Ferreira is a medical student holding an intern position at Luminare. Unlike Dr. Velamuri, David McCants, MD is not affiliated with Luminare, Inc. with no financial or proprietary conflicts of interests.