Edited by: Em. Professor Gualberto Buela-Casal

(University of Granada, Granada, Spain)

Dr. Katie Almondes

(Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, NATAL, Brazil)

Dr. Alejandro Guillén Riquelme

(Valencian International University, Valencia, Spain)

Last update: December 2025

More infoWar profoundly impacts various aspects of human life. The effects of war on sleep have been mainly studied among military personnel who are directly exposed to combat. The present work studies changes in sleep patterns of the civilian population following a war, assessing sleep before and during the 2023-2024 Israel–Hamas war.

MethodsStudy 1 compared the national prevalence of insomnia before and during the war by analyzing data from the 2023 Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics survey (N = 6,474). Studies 2 and 3 comprehensively assessed reports on sleep before the war and 2-3 months into the war through validated tools, and also measured psychological distress and demographics. These studies included two independent samples (N = 1,706), one of which was representative of the Israeli population. Study 4 re-surveyed the representative sample of Study 3 six months into the war (N = 273).

ResultsIn Study 1, the incidence of insomnia symptoms rose markedly during the war. In Studies 2 and 3, participants reported a 19-22 % increase in the prevalence of short sleep (< 6 hours/night), a 16-19 % increase in clinical insomnia, and a 4-5 % increase in sleep medication usage compared to before the war. In Study 4, 6 months into the war, the majority of sleep impairments persisted despite reduced psychological distress. Across studies, women and individuals with greater exposure to trauma were more strongly affected.

ConclusionsThe findings of four studies demonstrate the detrimental effects of warfare on civilians’ sleep, indicating that these effects are likely long-lasting. The findings identify precursors for sleep problems and underscore the relationships between sleep, trauma, and psychological distress.

Brief Summary

Current knowledgeWar is an event of profound magnitude that alters the lives of many. The effects of war on people’s sleep have been mainly studied among combat-exposed military personnel. How does war impact the sleep patterns of the civilian population?

Study ImpactThis comprehensive population-based study, conducted in 2023-2024 before and during the Israel–Hamas war, found that the Israeli civilian population experienced increased clinical insomnia, a significant reduction in sleep duration, and greater use of sleep medications, accompanied by high levels of psychological distress. The effects on sleep persisted 6 months into the war. The sleep of women and individuals with greater exposure to trauma was particularly affected. These findings call for sleep-targeted interventions in the context of war-related trauma and psychological distress.

Sleep is essential for the proper function of the body and mind. Inadequate sleep raises the risk for numerous health conditions, including heart attacks, diabetes, obesity, and cancer (Chung et al., 2024; Lloyd-Jones et al., 2022; Nock et al., 2009; Ramar et al., 2021). Inadequate sleep is also associated with an increased likelihood of developing mental disorders, such as anxiety, depression, and suicidal tendencies (Palagini et al., 2022; Perlis et al., 2016). Further, it carries psychological costs, broadly impairing cognitive and emotional functioning (Alhola & Polo-Kantola, 2007; Ben Simon et al., 2020; Brownlow et al., 2020; Choshen-Hillel et al., 2021). For example, it has been shown that interrupted sleep impairs memory and executive function, intensifies feelings of loneliness, and reduces empathy for the pain of others (Ben Simon et al., 2020; Ben-Simon & Walker, 2018; Choshen-Hillel et al., 2022; Choshen-Hillel & Gileles-Hillel, 2021; Gordon et al., 2021; Gordon-Hecker et al., 2025). On a societal level, sleep problems increase car and work-related accidents, reduce work productivity, and hinder prosocial behavior (Barnes & Wagner, 2009; Barnes & Watson, 2019; Bioulac et al., 2017; Holbein et al., 2019; Ishibashi & Shimura, 2020).

In the present work, we investigate the effects of prolonged exposure to war on the sleep of the civilian population. Research to date on war-related sleep disturbances, such as insomnia and nightmares, has mainly explored combat-exposed military personnel and first responders. The studies focused on combat-related factors and individual characteristics predisposing soldiers to the development of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and the associated sleep disturbances (Dow et al., 1996; Saguin et al., 2021). Studies examining the aftermath of natural and man-made disasters have found an increased prevalence of insomnia among those directly exposed to the traumatic event. For instance, the responders to the World Trade Center terror attacks in the United States experienced increased PTSD-related insomnia symptoms (Slavish et al., 2023). Similarly, the Fukushima nuclear disaster in Japan resulted in elevated rates of insomnia and nightmares among the plant workers (Ikeda et al., 2019).

Less is known about the impact of war on the civilian population. Notably, the civilian population is a large and diverse group, and the impact on this population is of significant importance from a public health standpoint. On average, civilians are exposed to war less directly than military personnel, but nevertheless, they, too, may endure significant suffering over extended periods. Anecdotal reports from World War II pointed to sleep disturbances among civilians exposed to bombings and air raids (Jones et al., 2004). These disturbances were often the direct result of spending a sleepless night in a bomb shelter. More recent studies provide some initial clues into the effects of war on civilian sleep, most of them involving samples of limited size and examining a single indicator of immediate changes in sleep, with no clear baseline for comparison. During the Gulf War in 1991, which affected Israel for around a month, high levels of acute insomnia were reported among a sample of 200 Israeli civilians (Lavie et al., 1991). In an analysis of US national data one month following the World Trade Center terror attacks, a 10–12 % increase in the prescription of new sleeping aid medications was found (Lamberg, 2001). Investigations of small samples of refugees escaping from conflict zones, such as Ukraine and Iraq, have found an increased prevalence of insomnia (Boiko et al., 2024; Lies et al., 2021). Finally, a 2022 cross-sectional report from the Gaza Strip found a high prevalence of sleep disturbances among a sample of the Palestinian population (Msaad et al., 2023), who live in a constant state of conflict.

The present study aims to fill some notable gaps in the scientific understanding of how exposure to war affects sleep. Our first goal was to provide a comprehensive description of war-related changes in the sleep of the civilian population by examining multiple aspects of sleep quantity and quality. We assessed changes in sleep health, a multi-dimensional construct important for physical and mental well-being (Lim et al., 2023; Ramar et al., 2021; Smith & Lee, 2022), as well as the emergence of sleep disturbances following the onset of the war. In particular, we assessed sleep satisfaction and sleep duration, insomnia symptoms, and the use of sleep medications. Sleep is known to be susceptible to changes following stressful life events such as the loss of a loved one, divorce, or living through a pandemic (Hisler & Twenge, 2021; Kalmbach et al., 2018; Mandelkorn et al., 2021; Yap et al., 2020). We hypothesized that immediately following the war, civilians would experience difficulties in falling asleep, maintaining uninterrupted sleep throughout the night, or sleeping long enough to feel rested during the day and would use more sleeping pills.

Our second goal was to follow changes in sleep patterns longitudinally, testing whether acute sleep disturbances in the immediate term (2-3 months into the war) develop into chronic sleep disturbances over time (6 months into the war). This goal is of importance given the findings that individuals with more severe symptoms of acute insomnia (i.e., clinical insomnia disorder) are at risk of developing chronic persistent insomnia or experiencing relapse after the initial remission of insomnia (Morin et al., 2009; Walker et al., 2022).

Our third goal was to identify factors that render the sleep of certain individuals more vulnerable or resilient in the face of war and to identify factors predisposing to the development of chronic sleep disturbances. Generally speaking, the susceptibility to disruptions of sleep following stressful events varies between individuals. Women, as well as individuals who are exposed to more stress and individuals with pre-existing medical and mental health conditions, tend to be more vulnerable to sleep disruptions than others (Morin et al., 2015; Morin & Buysse, 2024). Based on this literature, we hypothesized that women and those with greater exposure to traumatic events might be more susceptible to sleep disturbances.

We tested the effects of war on Israeli civilians’ sleep in the context of the Israel-Hamas war. The war, which started on October 7th, 2023, following a massive terror attack on Israeli civilians, interrupted the daily routines of the Israeli populace, with many civilians being exposed to daily rocket and missile attacks and violent news reports. Many had friends or relatives who were injured, kidnapped, or killed, and some were evacuated from their homes (Feingold et al., 2024). A recent study estimates that around 5 % of the Israeli population may develop PTSD as a result of the October 7th war (Katsoty et al., 2024; Levi-Belz et al., 2024). The war has also impacted and threatened civilians’ livelihoods, with many losing their businesses and incomes.

Our research includes four studies, see Fig. 1 for a timeline. In Study 1, we examined how frequently Israelis reported experiencing symptoms of insomnia before or during the war. We analyzed data (N = 6,474) from a large nationally representative sample conducted by the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) in 2023 during the 9 months before the war (i.e., before October 7th) and the first 3 months of the war. In Studies 2 and 3, we expanded the assessment of sleep problems and sleep health. Participants were asked to complete several comprehensive questionnaires on their sleep before and during the war, as well as a questionnaire on psychological distress and trauma exposure. The sample of Study 2 was recruited through social networks, and that of Study 3 was surveyed to represent the adult Israeli population; both studies were conducted 2-3 months into the war and included the same measures. In Study 4, we re-surveyed the participants from the representative sample of Study 3, six months into the war, assessing the potential long-term, chronic effects of the war.

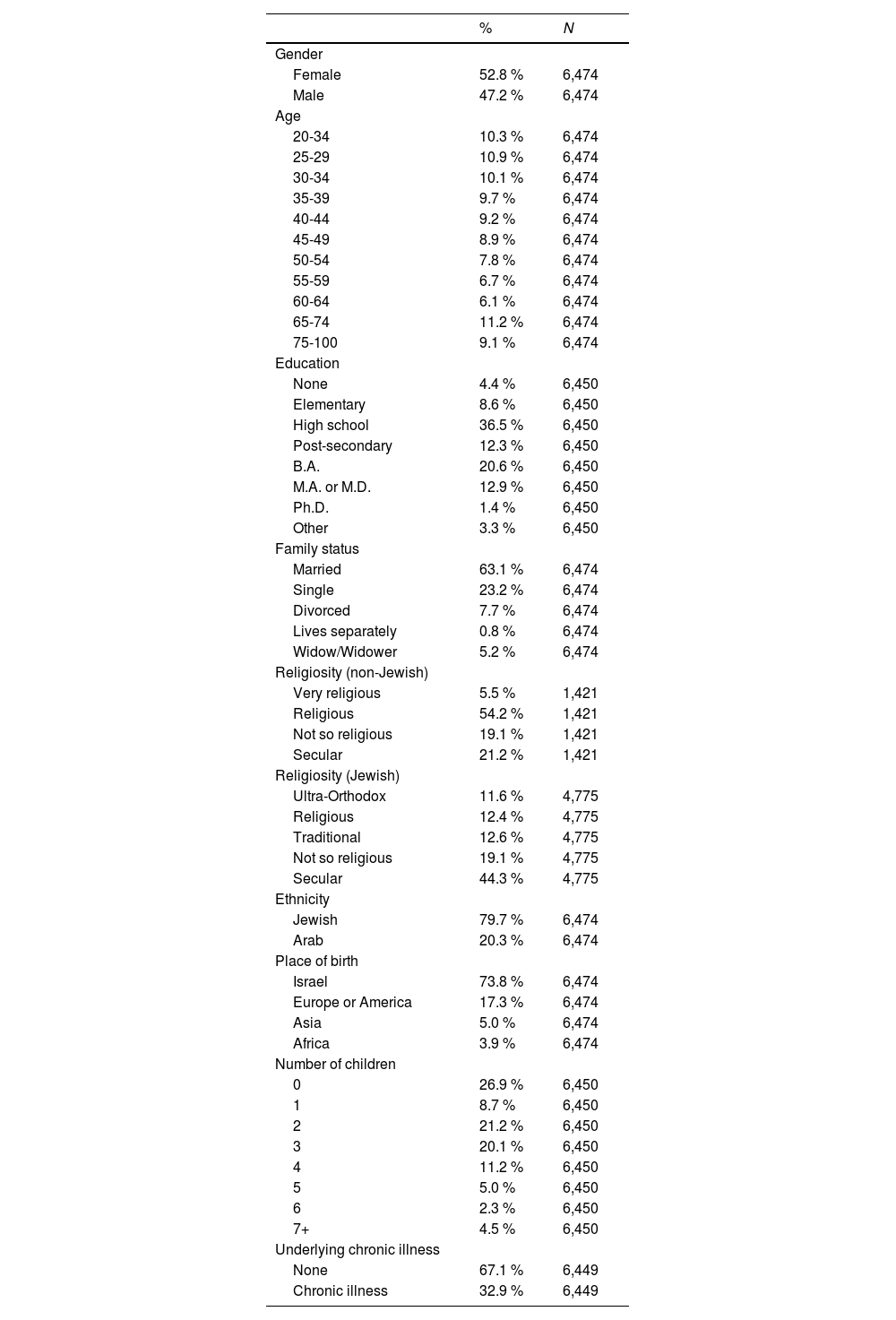

MethodsStudy 1Participants and procedureThe data for Study 1 were collected by the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) as part of the National Social Survey. The purpose of the National Social Survey is to provide up-to-date information on the welfare and living conditions of the adult population in Israel. The 2023 survey sample size was designed to achieve 7,500 participants, serving as a nationally representative sample of persons aged 20 or over. Out of 9,608 people approached, 6,474 responded (67.3 % response rate). The participants’ sociodemographic characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the nationally representative sample collected by the Israeli CBS in Study 1.

The survey questionnaire is made up of two main parts: a permanent core containing about 200 fixed questions on a variety of areas such as health, housing, employment, and financial status; and a variable module, which focuses on one or two topics each year that are investigated in-depth. The focus of the 2023 survey was Health and Way of Life. For a detailed description of the Israeli CBS survey methodology, see (Central Bureau of Statistics, n.d.).

The Israeli CBS does not disclose the specific dates of interviews, but in 2023, it added an indication of whether each interview was conducted before the war (i.e., between January 1, 2023, and October 6, 2023; 68 % of participants; N = 4,406) or during the war (between October 7, 2023, and December 31, 2023; 32 %; N = 2,068).

MeasuresThe 2023 Social Survey included a question about current insomnia symptoms. Participants were asked: “In the past three months, did you experience insomnia – having difficulties falling asleep, sleeping continuously throughout the night, or sleeping until the planned time in the morning?” Participants had to choose one of the following response options: “Never or less than once a month,” “More than once a month but less than once a week,” “1-2 times a week,” and “3 times a week or more.” The instructions for the interviewer defined “difficulty” as a problem lasting at least half an hour. Two additional questions about sleep duration were presented to participants, but they referred to “typical times,” making them irrelevant for assessing potential changes in sleep patterns related to the war.

Statistical analysisWe compared the frequencies of participants reporting each of the four levels of insomnia before and during the war, employing chi-squared tests. We also defined symptoms consistent with insomnia disorder (i.e., insomnia symptoms experienced three or more times a week in the past three months; Sateia, 2014) and compared the proportions of participants reporting such symptoms before and during the war, employing two-sample tests of proportions.

Studies 2 and 3ParticipantsStudy 2. Adult Israeli civilians (18 years or older) were invited to complete a study on the effects of the war on their daily routines. Invitations were circulated through social platforms and personal communications. The advertised goal of the study was to study changes in lifestyle following the war, and sleep was never mentioned. Participation was voluntary, and no compensation was offered. A total of 1,211 participants completed the study (78.7 % females; age: M = 45.40 years, SD = 15.52, range = 18–88). The participants’ sociodemographic characteristics are presented in Table 2.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the samples of the Israeli adult civilian population, Studies 2 and 3.

Study 3. Participants were recruited through iPanel, an online Israeli research panel. As in Study 2, sleep was not mentioned in the recruitment process. Invitations were sent to 1,817 individuals, aiming to reach a predetermined representative quota of 500 participants. The invitations were available for three days, after which a total of 495 civilians were sampled to match the Israeli adult population on four dimensions: ethnicity (80 % Jewish; 20 % Arab), gender (50 % female; 50 % male), age (for Jews, 50 % aged 18–40 and 50 % aged 41–70; for Arabs, 50 % aged 18–35 and 50 % aged 36–70), and religiosity/religion (for Jews, 50 % secular, 30 % traditional, and 20 % religious; for Arabs, 80 % Muslim, 12 % Druze, and 8 % Christian). Sociodemographic characteristics are presented in Table 2. Participants received gift cards for their participation, according to iPanel’s protocol (worth 5 NIS, which was approximately 1.35 USD).

ProcedureStudies 2 and 3 (and also Study 4, see below) were distributed online using Qualtrics software (Qualtrics, Provo, UT). The studies were distributed in Hebrew. An English-translated version can be found online at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/D69CE. Studies 2 and 3 were conducted two to three months into the war, during December 2-31, 2023, and December 24-26, 2023, respectively. Participants were informed that their data would be kept anonymous and that they were allowed to skip any study questions. The studies were approved by the Hebrew University Business School’s Institutional Review Board, #032_11_2023.

MeasuresStudies 2 and 3 included measures of sociodemographic characteristics, changes in daily routine since the war, exposure to trauma since the war, sleep measures before the war, sleep measures since the war, and psychological distress. Below, we report in more detail the measures used in the studies. All questions, in the order they appeared in the questionnaire, are available online at the OSF link above. The only difference between the questionnaires of Studies 2 and 3 was that some sociodemographic questions asked at the end of Study 2 were asked at the beginning of Study 3 to allow the selection of a representative sample.

Sociodemographic characteristics. Participants were asked to report their sociodemographic characteristics, including gender, age, education, family status, religiosity, ethnicity, country of birth, number of children, and the age of their youngest child. They were also asked to indicate whether they had previously been diagnosed with any chronic illness.

Changes in daily routine since the war. Participants were asked to report potential changes in their routine since the war, including changes in livelihood, physical activity, volunteering, relocation, and alcohol consumption.

Exposure to trauma since the war. Participants were asked four questions gauging their personal relationships with individuals affected by the war. In particular, they were asked to indicate whether or not they personally knew individuals who, during the war, were (a) hurt, (b) taken captive or missing, (c) killed, or (d) whose family members were killed, taken captive, or missing. The answers to these four questions were aggregated into an exposure to trauma scale ranging from 0 to 4 (no coded as 0; yes as 1).

Sleep measures. Sleep health and sleep disturbances were measured using several validated self-report tools, aiming to study different sleep domains. Participants were first asked to complete all sleep measures regarding their sleep before the war. Then they were asked to complete the same measures, now regarding the period since the beginning of the war. Each measure was calculated separately for reports before the war and during the war. Self-reported sleep duration was categorized into 6 hours of sleep or more (coded as 0) or less than 6 hours of sleep (coded as 1) (Shockey & Wheaton, 2017). Sleep health was measured using a five-item RU-SATED scale (Buysse, 2014), with an overall score ranging from 0 (poor sleep health) to 10 (good sleep health).1 Poor sleep health was defined as a RU-SATED score ≤ 5 for a binary measure. Insomnia symptoms were assessed using the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI; (Bastien et al., 2001)), where scores ranged from 0 to 28, and were categorized into four insomnia severity levels: non-clinical (0–7), subthreshold (8–14), moderate (15–21), and severe (22–28). Each participant reported the ISI scores both for the two weeks before the war and the last two weeks. Clinical insomnia was defined as an ISI score > 14, i.e., moderate or severe (Bastien et al., 2001). Participants were next asked to report whether or not they suffered from any sleep problems and whether or not they used any sleeping pills (no coded as 0; yes as 1). Specific medication types or dosages were not recorded. Finally, participants were asked whether or not they had experienced a change in their dream patterns since the war. Those who answered they did, were asked to describe the change in an open-ended question. Their responses were categorized into dreams with negative content (e.g., “nightmares”) or non-negative content. See the Appendix for a description of the categorization process.

Psychological distress. The six-question Kessler scale (K6) was used to measure psychological distress levels (Kessler et al., 2003). The questionnaire asked participants to relate to their feelings during the 30 days preceding participation in the study. The distress score ranged from 0 to 24, with 0-12 categorized as no significant psychological distress and 13–24 as significant psychological distress (Kessler et al., 2003).

Statistical analysisFor each study separately (2 and 3), we first compared each participant’s sleep measures before and during the war, using paired t-tests and two-sample tests of proportions. Second, to examine how specific sociodemographic variables, daily routine changes, and exposure to trauma were associated with changes in sleep health and disturbances, we used linear regression analyses. For participant i, the model was:

where Changei, the dependent variable, reflects participant i’s change in sleep between before and during the war (using one measure in each regression). The vector Sociodemographicsi includes a set of indicators for female gender, age group, having a child under six years old, education, family status, religiosity, whether the participant was born in Israel, ethnicity, number of children, and having an underlying chronic illness. The vector Routinechangesi includes another set of indicators for self-reporting an adverse (versus no) effect on livelihood, being more or less (versus similarly) physically active, devoting more or less (versus the same) time to volunteering, number of times relocated due to the war, having access to a bomb shelter or residential secure space, and consuming alcohol more or less frequently (versus as frequently as before). The variable Exposurei relates to the level of exposure to trauma. Finally, the error term, εi, is heteroskedasticity-robust.Study 4Participants and procedureStudy 4 was distributed about six months into the war, from April 1-14, 2024. In particular, the Jewish participants of Study 3 (78.0 % of participants; N = 386) were invited to participate in a follow-up study. Arab participants were not invited to participate again due to the Ramadan month that occurred at that time, which likely affected their daily routines and sleep (Roky et al., 2003).

A total of 273 participants completed Study 4 (70.7 % response rate, which is iPanel’s average response rate for follow-up studies). Of the participants, 59.4 % were females; age: M = 41.67 years, SD = 11.33, range = 18–70. Participants received gift cards for their participation (worth 2 NIS, which was approximately 0.55 USD).

MeasuresParticipants in Study 4 were presented with the same sleep and distress measures as in Studies 2 and 3, and asked to report only on their current sleep and distress. No additional measures were collected.

Statistical analysisFor each participant, we compared their reports on sleep and distress in Study 4 to their reports in Study 3 on (a) their sleep and distress (about three months before Study 4) and (b) their sleep before the war. We used paired t-tests and two-sample tests of proportions.

ResultsStudy 1Participants who were interviewed during the war reported different frequencies of experiencing insomnia than those who were interviewed before the war (χ² (3, N = 6,410) = 88.86, p < 0.001, Cramér's V = 0.118, see Fig. 2). Notably, more participants reported severe symptoms consistent with insomnia disorder during the war (22.0 %) than before the war (16.7 %, p < 0.001).

Frequency of insomnia in a national sample of the adult Israeli population, collected throughout 2023 by the Israeli CBS, Study 1 (N = 6,474 participants). Proportions are depicted with 95 % confidence intervals for each category, calculated based on the entire sample without using sampling weights (which were not designed to account for comparisons between before and during the war).

Women who were interviewed during the war reported different frequencies of insomnia than women who were interviewed before the war (χ² (3, N = 3,378) = 70.53, p < 0.001, Cramér's V = 0.145). Similarly, men who were interviewed during the war reported different frequency of insomnia than men who were interviewed before the war (χ² (3, N = 3,032) = 27.68, p < 0.001, Cramér's V = 0.096). Note that the effect size was larger among women. Moreover, women who were interviewed during the war were significantly more likely to report symptoms of an insomnia disorder (27.8 %) than women interviewed before the war (19.1 %, p < 0.001). For men, this difference was not significant (15.3 % during the war and 14.1 % before the war, p = 0.41).

Studies 2 and 3Descriptive statisticsDescriptive statistics of all measures for Studies 2 and 3 are presented in Table 2 (sociodemographic characteristics), Table 3 (sleep measures), and Table 4 (changes in daily routine, exposure to trauma, and psychological distress). Because participants could skip questions, different measures have slightly different numbers of observations. Of note, 33.8 % of participants in Study 2 and 37.9 % in Study 3 indicated they personally knew individuals who were killed during the war. Moreover, 31.6 % of participants in Study 2 and 32.5 % in Study 3 were categorized as suffering from significant psychological distress. Among participants describing changes in their dream patterns, 52.0 % of changes in Study 2 and 62.3 % in Study 3 were categorized as negative.

Sleep measures in the samples of Studies 2 and 3.

Significance levels. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001

Notes. The confidence level (CI) was calculated using (a) paired t-tests for RU-SATED, ISI, and sleep duration and (b) two-sample tests of proportions for the dichotomous measures. Two-tailed p-value categories are indicated accordingly.

Changes in daily routine, exposure to trauma, and psychological distress in the samples of Studies 2 and 3.

Correlations. The correlations between reports of sleep measures (regarding the period before and during the war), exposure to trauma (during the war), and psychological distress (during the war) are reported in Table 5. Overall, these correlations suggest that trauma exposure and psychological distress are associated with sleep health and sleep disorders. As expected, these correlations were more pronounced after the onset of the war. Correlations between reports regarding the period before the war and during the war for each of the sleep measures are provided in Table S2 in the appendix.

Correlations between reports of sleep measures (regarding the period before and during the war), exposure to trauma (during the war), and psychological distress (during the war) in Studies 2 and 3.

Significance levels. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

Notes. Correlations were calculated using listwise/casewise deletion of missing values, omitting observations that involved a missing value for any of the included measures.

Study 2. On average, participants who were recruited 2-3 months into the war, reported that they slept ∼30 minutes less per night during the war (M = 6.41 hours) than before the war (M = 6.86 hours, p < 0.001). More participants reported sleeping less than 6 hours per night during the war (31.3 %) than before the war (12.8 %, p < 0.001). The average sleep health measured by RU-SATED during the war (M = 6.32) was worse than before the war (M = 7.62, p < 0.001), and the proportion of RU-SATED ≤ 5 increased from 15.0 % to 38.0 % during the war (p < 0.001). Average Insomnia Severity Index increased from 4.50 to 8.35 during the war (p < 0.001), and clinical insomnia (ISI > 14) increased from 4.0 % to 20.2 % during the war (p < 0.001). This pattern of worse sleep during the war was also reflected in participants’ indications of having a sleep problem, which went up from 18.3 % to 47.7 % during the war (p < 0.001) and by the increased use of sleeping pills, that went up from 8.1 % to 13.3 % during the war (p < 0.001). Formal analyses are presented in Table 3, and proportions are depicted in Fig. 3a.

Sleep measures in the samples of Study 2 (panel a; N = 1,211 participants) and Study 3 (panel b; N = 495 participants). Proportions are depicted with 95 % confidence intervals. Differences between before the war and 2-3 months into the war were statistically significant (see also Table 3).

Study 3. Changes in reported sleep since the war among participants in Study 3 closely resembled those reported in Study 2, despite apparent variations in sample characteristics (see Table 2). The results are presented in Table 3 and Fig. 3b.

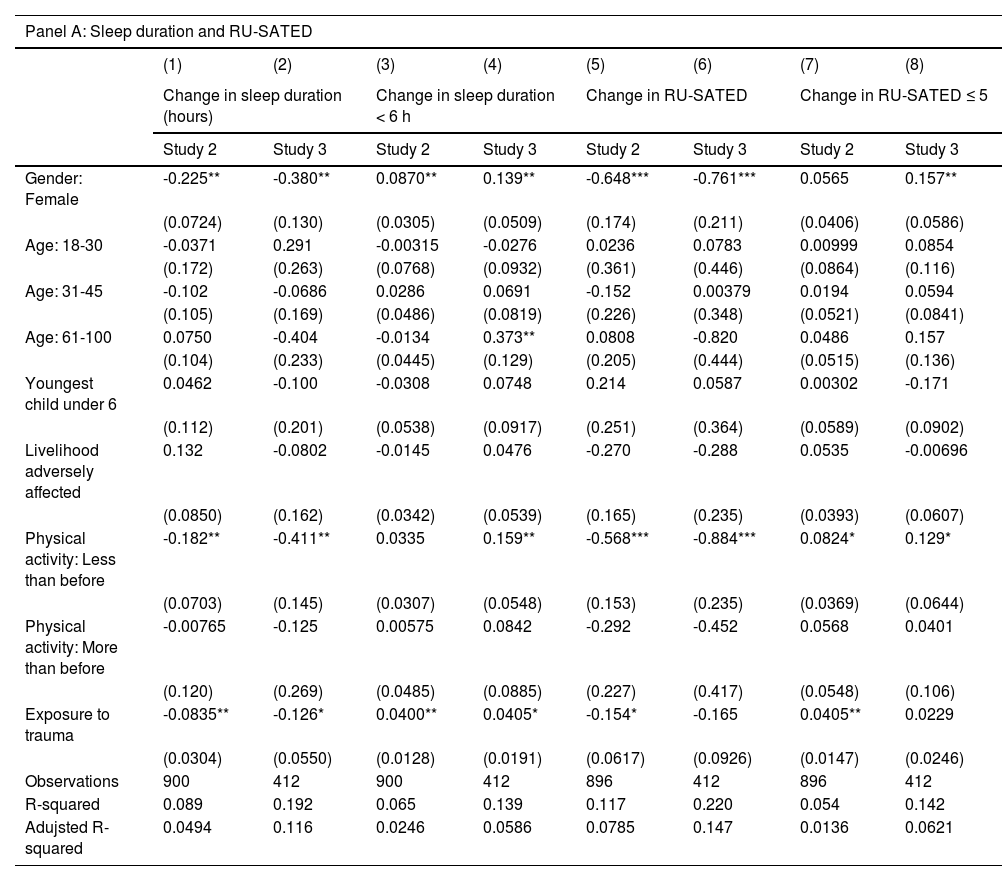

Predictors of worsening sleepStudy 2. Regression analyses indicated that all else being equal, women were significantly more susceptible to negative changes in sleep since the war than men. This included a greater reduction in reported sleep duration, a greater increase in reporting sleeping less than 6 hours per night, a greater decrease in RU-SATED scores, a greater increase in ISI scores and ISI scores indicating clinical insomnia, and a greater increase in reporting a sleep problem. For example, a female participant was 12.9 percentage points more likely to report a negative change in having a sleep problem since the war than a male participant with similar characteristics (Column 5 of Table 6, Panel b). No association was found between the female gender and a change in the proportion of RU-SATED ≤ 5 or the use of sleeping pills.

Multivariate regression analyses predicting changes in sleep measures following the war, Studies 2 and 3.

Significance levels. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001

Notes. Heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors are presented in parentheses.

All of the models were estimated by ordinary least squares.

Additional controls were included, as described in the data analysis section.

Exposure to trauma was also significantly associated with worsening sleep since the war. All else being equal, participants with higher exposure to trauma reported a greater reduction in sleep duration, a greater increase in sleeping less than 6 hours per night, a greater decrease in RU-SATED scores, a greater increase in RU-SATED ≤ 5, a greater increase in ISI scores and ISI scores indicating clinical insomnia and a greater increase in sleep problems. For example, greater exposure to trauma was associated with an increased likelihood (3.0 percentage points) of reporting a negative change in having a sleep problem (Column 5, Table 6 Panel b). Exposure to trauma was not associated with a change in the use of sleeping pills.

Study 3. Once again, the patterns observed in Study 3 were highly similar to those observed in Study 2 (see Table 6).

Study 4In Study 4, we followed up on the sleep patterns of most participants from Study 3, six months into the war. Participants reported a decrease in the prevalence of significant psychological distress (from 32.0 % to 20.6 %, p = 0.004). Sleep measures for these participants span over three periods: before the war (Study 3), 2-3 months into the war (Study 3), and six months into the war (Study 4). Participants reported they were still sleeping fewer hours per night (M = 6.20) on average than they used to sleep before the war (M = 6.94 hours, p < 0.001), similar to their reports 2-3 months into the war (M = 6.22 hours, p = 0.827). Correspondingly, more participants reported sleeping less than 6 hours per night (35.7 %) than before the war (12.8 %, p < 0.001), similar to reports 2-3 months into the war (38.0 %, p = 0.584). The average sleep health measured by RU-SATED six months into the war (M = 6.32) was worse than before the war (M = 7.62, p < 0.001). Still, it was better than 2-3 months into the war (M = 5.67, p < 0.001). Also, the rate of scores indicating RU-SATED ≤ 5 was higher six months into the war (36.8 %) than before the war (10.9 %, p < 0.001) and lower than 2-3 months into the war (48.4 %, p = 0.008).

The same pattern was observed in the average scores of the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI). Average insomnia scores six months into the war (M = 8.52) were higher than before the war (M = 4.74, p < 0.001) but lower than 2-3 months into the war (M = 9.64, p = 0.002). More participants indicated clinical insomnia six months into the war (23.0 %) than before the war (5.4 %, p < 0.001), similar to 2-3 months into the war (26.1 %, p = 0.412). The rate of indicating a sleep problem was higher six months into the war (42.7 %) than before the war (15.7 %, p < 0.001) and similar to the rate 2-3 months into the war (48.6 %, p = 0.182). Finally, participants reported about the same use of sleeping pills six months into the war (5.0 %) as before the war (5.8 %, p = 0.698) and marginally less use compared to 2-3 months into the war (9.2 %, p = 0.061). Formal analyses are presented in Table 7, and proportions are depicted in Fig. 4.

Sleep measures of participants in Study 4 (6 months into the war), vs. the same participants in Study 3 (2-3 months into the war, and before the war).

Significance levels. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001

Notes. The confidence level (CI) was calculated using (a) paired t-tests for RU-SATED, ISI, and sleep duration and (b) two-sample tests of proportions for the dichotomous measures. Two-tailed p-value categories are indicated accordingly.

The present research examined the changes in sleep patterns in the Israeli civilian population following the Israel-Hamas war. Study 1, conducted before and during the war as part of the National Social Survey by the Israeli CBS, documented an increased report of insomnia symptoms in the adult Israeli population during the war. In Studies 2 and 3, conducted two to three months into the war, participants reported a marked deterioration in their sleep health and multiple other sleep-related measures, compared to the period before the war. Participants reported a 16-19 % increase in clinical insomnia, a 19-22 % increase in the prevalence of short sleep (< 6 hours per night), and a 4-5 % increase in sleep medication usage compared to before the war. Women, as well as people with greater exposure to trauma, suffered more pronounced disruptions to their sleep following the war. Around a third of the participants reported significant psychological distress. The impairment in different sleep health measures emerged both in Study 2’s sample and in Study 3’s representative sample of the adult Israeli population. Study 4 re-evaluated most of the participants from the representative sample of Study 3, six months into the war. The majority of sleep disturbances persisted, including increased insomnia, reduced sleep duration, and reduced sleep health. Interestingly, some participants showed remission in some of their sleep problems, most notably in the RU-SATED measure. This suggests that not all sleep problems follow the same temporal trajectory and highlights a degree of adjustment in some individuals, as reflected in improved sleep satisfaction. Relatedly, there seemed to be some psychological adjustment marked by a decrease in the prevalence of significant psychological distress, although the levels of psychological distress remained higher than what is generally considered a population average in other settings (Mewton et al., 2016).

The results of our four present studies underscore the perils of war in the domain of sleep, with dire implications for public health. Firstly, we observe the development of chronic sleep disturbances, marked by the persistence of many complaints at the six-month evaluation. The increased prevalence of severe insomnia symptoms, consistent with an insomnia disorder, further heightens the risk of future chronic complaints (Morin et al., 2009). It is known that some individuals continue to suffer from insomnia even a decade after a stressful event (Morin & Benca, 2012). Additionally, the high prevalence of participants reporting short sleep duration in our studies, especially those sleeping less than six hours, is concerning due to its detrimental effects on both physical and mental health (Watson et al., 2015). The increased consumption of sleep medications at the beginning of the war is also worrisome due to their highly addictive nature and significant adverse effects (Besag et al., 2019; Bushnell et al., 2022). It is somewhat reassuring that medication usage returned to baseline despite the persistence of sleep disturbances. However, the high prevalence of significant psychological distress observed at 2-3 and 6 months is particularly concerning, as it is generally a strong predictor of serious mental illness (Kessler et al., 2003).

Across our studies, women reported, on average, greater impairment in their sleep health following the war than men. This finding is in line with previous findings on women’s greater vulnerability to developing insomnia (Morin et al., 2015), which has been related to hormonal and psychosocial differences, gender differences in circadian rhythms (Boivin et al., 2016; Lok et al., 2024; Morin et al., 2015), and differences in response to a potentially traumatic event (Milanak et al., 2019). Women are also more prone to suffer from anxiety and mood disorders, which are closely linked to insomnia (Ben-Simon et al., 2020; Goldstein-Piekarski et al., 2018). Women’s greater sleep impairment following the Israel-Hamas war is also in line with the findings of a recent study showing that Israeli women were more likely than men to report substance abuse in the first month of the Israel-Hamas war, even though men are typically more prone to substance abuse (Eliashar et al., 2024).

The current results also reveal that individual levels of exposure to traumatic events (such as having a 1st-degree relative injured or killed on October 7th) led to increased risk for experiencing sleep disturbances even when adjusted for individual and sociodemographic factors. This finding aligns with the existing literature documenting an association between exposure to trauma and subsequent sleep disturbances. Notably, the association between sleep disturbances and trauma is bidirectional. It has been shown that sleep disturbances can exacerbate post-traumatic symptoms and even increase the risk of PTSD development (Lies et al., 2021; Mysliwiec et al., 2018; Slavish et al., 2023). In our samples, sleep disturbances in the period before the war were associated with the degree of psychological distress during the war, further strengthening the bi-directional association between sleep and psychological trauma. Future longitudinal studies should examine whether individuals with increased sleep disturbances following war are at an increased risk for developing PTSD.

A key contribution of the findings presented here is in bringing to awareness the dramatic effect of war on civilians’ sleep. Such awareness should lead to policy recommendations and the adoption of public health strategies (Neria et al., 2025). Healthcare providers, mental health specialists, and community workers in conflict-affected areas should be educated about sleep problems in times of war. These efforts may include expanding resources for sleep clinics, incorporating sleep health assessments into routine care during extended periods of conflict, and adjusting workplace or educational policies to accommodate the sleep and fatigue issues prevalent among civilian populations affected by war. Public health authorities should consider implementing awareness campaigns focused on educating the population about healthy sleep practices, appropriate use of sleep medications, and when to seek professional help. On a broader policy level, our data underscore the need for incorporating sleep into the mental health support systems in times of crisis.

Strengths and limitationsThe present work has some notable methodological strengths. First, to the best of our knowledge, it is the largest and most comprehensive study exploring the effect of war on civilians’ sleep. The multi-faceted assessment of sleep, performed using several validated tools, provides a comprehensive picture of the impact of war on sleep health and sleep disturbances in the population. In contrast to most prior studies in the field, which focused on a single sleep domain—typically insomnia—the current approach takes a broader perspective (Boiko et al., 2024; Lavie et al., 1991). Second, the studies surveyed several representative samples of the Israeli population, including both Jewish and Arab citizens. Third, by following a subset of participants up to six months into the war, we were able to record the long-term effects that extend beyond those of the initial phase of the beginning of the war, specifically beyond 3 months, fulfilling the definitions of a chronic disorder (Morin et al., 2015).

Despite these strengths, the study is not without limitations. First, Studies 2-4 rely on participants’ self-reports on their sleep before and during the war. Whereas self-reported sleep quality has been strongly associated with psychological well-being and daytime function (Muzni et al., 2021), the reports on sleep before the war could have been biased because they were made retrospectively during the war. The data from Study 1, which was collected before and also during the war, provides some validation, although it only includes one item on insomnia symptoms. Another, more detailed validation for the self reports on sleep before the war in Studies 2-3 can be found in data from the 2017 national survey of the Israeli CBS (N = 7,230) (The Social Survey 2017, 2019), which included several items on sleep. In 2017, 17 % of the Israeli adult population reported sleeping less than 6 hours a night, similar to 13-14 % reported in the present Studies 2 and 3. In 2017, 15 % complained of persistent difficulties falling and staying asleep, which is similar to the 16-18 % reporting a sleep problem in Studies 2 and 3. Finally, in 2017, 7 % reported using sleeping medications, which is similar to the 6-8 % reported in Studies 2 and 3. The 2017 pre-war baseline thus validates participants’ self-reports on their sleep before the war, further instantiating the dramatic changes in sleep during the war.

Another potential limitation in Studies 2-4 may be the selection bias towards participants with sleep problems due to their greater interest in this topic. Study 1, being a national social survey, is not subject to this problem because it is conducted yearly, was unaffected by the war, and includes a wide range of topics. To counter this possibility in Studies 2-4, the advertisement described general behaviors and did not mention sleep in particular. An additional limitation relates to the fact that we did not collect information on the specific types of sleep medications used (e.g., Z-drugs, benzodiazepines, melatonin). This level of granularity would be important for future public health efforts aimed at understanding and potentially reducing sleep medication use. Finally, it should be noted that all of our studies have examined the civilian population in a certain conflict area under particular war circumstances. The effects of war on the civilian population may depend on the local characteristics of war, somewhat limiting the generalizability of the present findings.

ConclusionsOur research documents the dramatic impact of the Israel-Hamas war on the sleep of Israeli civilians. Sleep impairment remained at significant levels six months into the conflict, suggesting chronic effects. Chronic sleep problems have profound implications for physical and mental health, as well as cognitive functioning. A recent line of research further highlights the detrimental effects of sleep problems on affective functioning and interpersonal behavior. Poor sleep has been shown to reduce prosocial behavior, decrease empathy for the pain of others, and increase feelings of loneliness (Ben-Simon & Walker, 2018; Choshen-Hillel et al., 2022; Holbein et al., 2019). In times of war, these effects may lead to greater frustration and escalation. Our findings highlight the need to address sleep as a component of mental and public health in conflict areas (Morin & Buysse, 2024).

Data availability statementThe data and code underlying this article are available at: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/D69CE

FundingAGH and SCH thank The Israel National Institute for Health Policy Research and also the United States-Israel Binational Science Foundation (grant #2022114) for funding. SCH thanks the Recanati Fund at the Hebrew University Business School at the Hebrew University.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing processDuring the preparation of this work, the authors used Chat GPT4 in order to improve the writing style. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the published article.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Alex Gileles-Hillel reports financial support was provided by The Israel National Institute for Health Policy Research. Alex Gileles-Hillel reports financial support was provided by United States-Israel Binational Science Foundation. If there are other authors, they declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

We thank Ms. Hani Sharabi and Mr. Avishai Cohen (Central Bureau of Statistics, Israel) and Mr. Ariel Karlinsky (Economics Department, Hebrew University of Jerusalem) for their valuable advice.

Equal first authorship.

The acronym SATED refers to Satisfaction with sleep, Alertness during waking hours, Timing of sleep, sleep Efficiency, and sleep Duration (Buysse, 2014); the correlations between these dimensions are reported in Table S1 in the Appendix.