Edited by: Em. Professor Gualberto Buela-Casal

(University of Granada, Granada, Spain)

Dr. Katie Almondes

(Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, NATAL, Brazil)

Dr. Alejandro Guillén Riquelme

(Valencian International University, Valencia, Spain)

Last update: December 2025

More infoSleep disturbances have been linked to later suicidality among adolescents. This study assessed the associations between sleep disturbances experienced at age 11 and the subsequent occurrence of suicide thoughts and suicide attempt measured at age 18.

MethodsSelf-reported data on sleep disturbances measured at age 11 was obtained from the Danish National Birth Cohort and linked to information on suicidality at age 18 based on self-reports and register-based data on hospital contacts for suicide attempt. Relative risk ratios(RRR) with corresponding 95 % confidence intervals were estimated using multivariable multinomial logistic regressions adjusting for sex, sociodemographic characteristics, psychiatric history, and child risk behaviors and procedures of inverse probability weighting were applied .

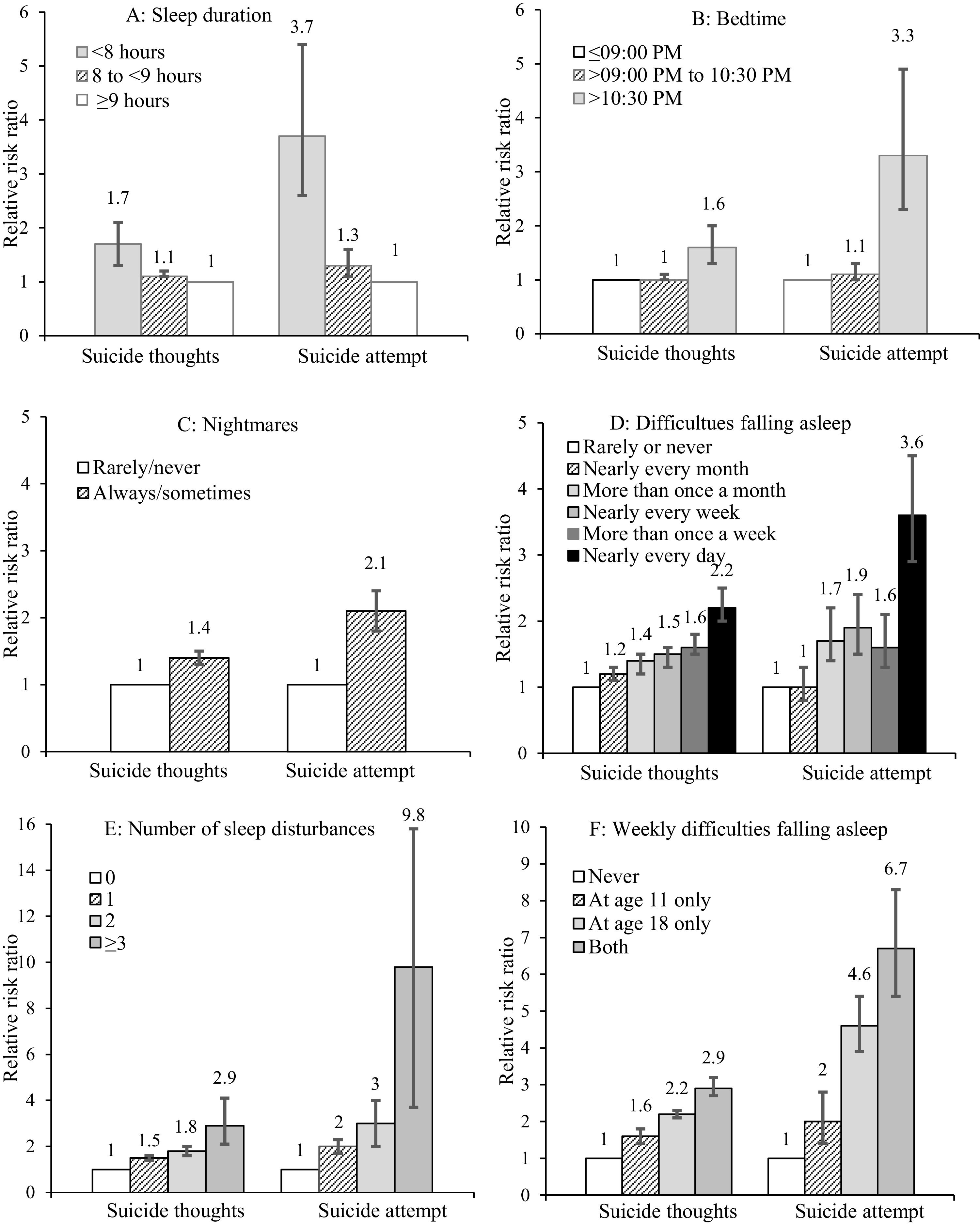

ResultsA total of 28,251 participants were included, of whom 8894 (32.0 %) reported suicide thoughts and 743 (3.3 %) attempted suicide at age 18. Adolescents who at age 11 reported sleeping <8 hours per night had elevated risk of suicide thoughts (aRRR, 1.7; 95 % CI, 1.3–2.1) and suicide attempt (aRRR, 3.7; 95 % CI, 2.6–5.4) when compared with those sleeping ≥9 hours. Going to bed after 10:30PM versus before 9:00PM on weekdays was associated with higher risks of suicide thoughts (aRRR, 1.6; 95 % CI, 1.3–2.0) and suicide attempt (aRRR, 3.3; 95 % CI, 2.3–4.9). Dose-response relationships documented that experiencing difficulties falling asleep more often was associated with higher risks of suicide thoughts and suicide attempts. Adjusting for child psychiatric co-morbidity attenuated results, however associations still showed statistical significance.

ConclusionSleep disturbances were associated with later suicidality among adolescents. Significant associations suggested that adequate hours of sleep and earlier bedtimes might protect against suicidality in children and adolescents.

Increasing rates of suicide attempts have been reported among adolescent over recent decades (Griffin et al., 2018; Morgan et al., 2017; Morthorst et al., 2016) This is concerning because suicide attempt is one of the strongest predictors for repeat suicide attempts and death by suicide (Large et al., 2021). Ideation-to-action theories argue that predictors may differ and that addressing both suicide thoughts and the progression to suicide attempt as two separate and distinct phenomena is vital (Klonsky et al., 2016). Among adolescents, suicidality (here defined as suicide thoughts and suicide attempt) has been linked to a broad range of sleep disturbances. Children and adolescents experience profound changes in sleep patterns and their circadian timing system (Carskadon, 2011; Crowley et al., 2018). Emotional and psychosocial factors may also impact their sleep quality. It is, therefore, highly relevant to examine the association between sleep disturbances and suicidality among adolescents. A recent meta-analysis showed that individuals with sleep disturbances had respectively 2.3- and 3.0-fold higher odds of suicide thoughts and suicide attempt compared with controls (Baldini et al., 2024). Further, disturbed sleep at age 10 had been associated with preadolescent suicide thoughts and suicidal behavior (Gowin et al., 2024). More specifically, suicidality has been associated with low sleep duration (Chiu et al., 2018; Gong et al., 2020; Guo et al., 2021), late bedtime (Gangwisch et al., 2010; Jeong et al., 2019), nightmares (Liu et al., 2019, 2021) and insomnia symptoms (Chen et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2019; Wong & Brower, 2012). Further, experiences of sleep disturbances during adolescence have been associated with psychiatric morbidity (Armstrong et al., 2014; McCurry et al., 2024) and emotional dysregulation (Palmer et al., 2024), which have been linked to suicide attempt (Hawton et al., 2012). Survey data has revealed that 29 % of 11-year-old Danish children had sleep durations, which were below the recommended 9 hours (Hirshkowitz et al., 2015; Ottosen et al., 2022), thus indicating that many adolescents potentially may be at risk. This is concerning because sleep disturbances are likely to persist until late teenage years for up to one in every third child with sleep disturbances earlier in life (Sivertsen et al., 2017). The existing body of evidence has mainly been confined to small sample sizes, which limits options of adjusting for potential confounders and cross-sectional data, which precludes assessment of temporal relationships, e.g. whether sleep disturbances existed before suicidality or vice versa. So far, relatively few measures of sleep disturbances have been examined in relation to suicidal behavior. To obtain a nuanced understanding, there is need for investigating the associations between different measures of sleep disturbances and suicide thoughts and attempt using a large sample.

Thus, utilizing a large national cohort, our objective was to assess whether sleep disturbances, i.e., low sleep duration, late bedtimes, nightmares, difficulties falling asleep, and cumulative number of different sleep disturbances, reported by adolescents at age 11 were associated with higher risk of suicide thoughts and suicide attempt at age 18.

MethodsStudy designWe applied a cohort design to longitudinal data from the Danish National Birth Cohort (2025), a birth cohort consisting of about 30 % of all children born in Denmark between 1996 through 2003 (https://www.dnbc.dk; Olsen et al., 2001). Women were invited to participate in the study by their general practitioner during their first pregnancy visit. Women who did not speak Danish well enough to take part in the telephone interviews and women who did not wish to carry their pregnancy to term were excluded. Follow-ups of their adolescent children were conducted at age 11 (DNBC-11) during July 2010 to August 2014 and at age 18 (DNBC-18) during April 2016 to January 2022. A total of 90 986 adolescents living in Denmark were invited to the DNBC-11 of which 49 956 (55 %) responded. Among the 89 377 who were invited to DNBC-18, 49 963 (56 %) responded. Data was collected via web-based questionnaires. Using the unique personal identification number assigned to all residents and listed in the Civil Registration System (CPR), an individual-level data linkage provided additional information on the adolescent and their parents from national registers.

ParticipantsIndividuals who had responded to all questions regarding sleep exposures in the DNBC-11 and all questions regarding suicide thoughts and suicide attempt in the DNBC-18 were included (Fig. 1). The final sample consisted of 28 251 adolescents (59.8 % females). At time of DNBC-11 follow-up, 84 % of participants were 11 years and 16 % were 12 years of age.

ExposureSleep duration was based on following questions: “At what time do you usually go to sleep on weekdays? and “When do you get wakened/waken on weekdays? (eTable 1 in Supplement) and calculated as the sum of hours between time going to bed and time waking up, classified as: <8 hours, 8 to <9 hours, and ≥9 hours. For children between 6 and 12 years of age, <9 hours of sleep is considered as insufficient (Crowley et al., 2018; Paruthi et al., 2016). Less than 8 hours was used as a lower cutoff to facilitate comparison with previous evidence which was also previously recommended by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and American Academy of Sleep Medicine (Baiden et al., 2020; Gong et al., 2020; Gunderson et al., 2023). Bedtime on weekdays was categorized as going to bed at: ≤9:00PM, >9:00PM to 10:30PM, and >10:30PM. We opted to use three categories to assess for a dose-response association between late bedtime and suicidality. Further, preliminary analyses revealed that most pre-teens (56.9 %) reported going to sleep before 9:00PM. Exposure to nightmares was identified using the question: “Do you have nightmares?” and categorized as always/sometimes and rarely/never. Information on difficulties falling asleep was derived from the question: “Look back over the latest 6 months. How often have you had difficulties falling asleep?” and categorized as: nearly every day, more than once a week, nearly every week, more than once a month, nearly every month and rarely or never. To account for several forms of sleep disturbances, number of sleep disturbances was defined by combining affirmative answers to each of the above listed four measures where a binary covariate (0/1) indicated exposure to a sleep disturbance, i.e., 1) sleeping <9 hours, 2) going to bed at >10:30PM, 3) always/sometimes having nightmares and 4) having weekly difficulties falling asleep. The summarized aggregate measure was categorized as 0, 1, 2, and ≥3. Further, information on weekly difficulties falling asleep measured at age 11 and age 18 derived from answers to two questions in the DNBC-11 and DNBC-18: “Look back over the latest 6 months. How often have you had difficulties falling asleep?” and “How often do you have trouble falling asleep?” and categorized as: never, at age 11 only, at age 18 only, and both. Participants who did not answer both questions were excluded (n = 124, 0.4 %).

OutcomeThe primary outcomes of suicide thoughts and suicide attempt were identified in DNBC-18. Suicide thoughts were based on the question: “Have you ever thought about taking your own life (even though you would not do it)?” and suicide attempt were based on the question: “Have you ever tried to kill yourself?” (eTable 2 in Supplement). Response options were no, yes and do not know. Adolescents who answered, ‘do not know' (4.4 %) were classified as having answered ‘no’. Data on suicide attempts was supplemented with information from hospital-records on probable suicide attempts registered before the date of completing the DNBC-18 and based on diagnostic codes from the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) (Lynge et al., 2011; Mors et al., 2011). Given that the majority of recorded deliberate self-harm episodes among infants, toddlers, and young children were evaluated to be accidents (Morthorst et al., 2016) we opted to only include incidents among persons aged 10 years or older. Self-reported and hospital-recorded data were combined into the following mutually exclusive categories: 1) no suicidality (i.e., no suicide thoughts and no suicide attempt); 2) suicide thoughts (and no suicide attempt); and 3) suicide attempt (self-reported or hospital-recorded).

Other measuresThe following covariates were included in the analyses: sex (male; female), parental educational level (elementary school; vocational education; high school; bachelor or higher), parental income (1st quartile to 4th quartile), parental occupational status (working/studying; not working) and living situation (living with both parents; not living with both parents), parental psychiatric disorders (no; yes), child psychiatric disorders (no; yes), level of stress (no stress; medium stress; high stress), quality of life (good; poor), self-harm (no; yes) and physical activity (very active; moderately active; a little active; not active). Psychiatric disorders were identified as any recorded diagnosis of a mental disorder (ICD-10: F00-F99; ICD-8: 290–315). Information on level of stress was captured through the 21 items Stress in Children Scale (SiC) questionnaire, which captured physical and emotional aspects of perceived stress (Emmanouil et al., 2020). Information on quality of life was obtained using Cantril’s ladder where general quality of life was measured on a scale from 0 to 10 (Cantril H (1965)). Lastly, self-harm was identified using the question “Have you ever tried to harm or hurt yourself?” with the response options no or yes. Participants who had not answered this question (n = 51) were categorized as having responded no. All covariates were measured in the DNBC-11 questionnaire or in the calendar year where the child reached age 11 if register-based. In eTable 3, each covariate is described with their data sources, operational definition and documentation for association with both exposure and outcome.

Statistical analysesInverse probability weighting was applied to account for any selection bias in the DNBC sample (Hernán et al., 2004; Nohr & Liew, 2018). A weight was assigned to each participant in the DNBC-11 to make the data sample representative for all individuals who were born in Denmark during 1996 through 2003 and alive on their 18th birthday (n = 449 228) with respect to sex, maternal birth age, parity of mother, parental educational level, parental income level, parental occupational status, living situation and psychiatric disorders (Table 1). The association between sleep disturbances (sleep duration; bedtime; nightmares; difficulties falling asleep; and number of sleep disturbances) and suicide thoughts and suicide attempts was examined using multinomial logistic regression analyses (Hilbe M, 2009). A significance level of 0.05 was used and adjusted relative risk ratios (aRRR) with corresponding 95 % confidence intervals (CI) were estimated. The basic model was adjusted for sex, while the fully adjusted model, in addition, was adjusted for parental educational level, parental income level, parental occupational status, living situation, and parental psychiatric disorders. Weights were applied to the regression estimates but not to the absolute numbers. In sensitivity analyses, the robustness of the associations was assessed by additionally adjusting for child psychiatric disorders, level of stress, quality of life, self-harm, and physical activity. In additional, separate models, we excluded: 1) children at age 11 who had reported self-harm at age 11 (n = 1666), 2) participants who answered ‘do not know’ to items about suicidality (n = 1233), and 3) participants registered with psychiatric diagnoses at any point before age 18 (n = 2562). This was done to account for potential confounding or mediation of severe psychiatric illness in the association between sleep disturbances and suicidality. Data management and analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4.

Characteristics at age 11 of the unweighted DNBC study population, background population, and the weighted DNBC study population.

An anonymized data set was used for the analyses, and the project was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (P-2020–305).

ResultsA total of 28 251 adolescents were included. Of these, 8894 (32.0 %; 57.4 % females) and 743 (3.3 %; 72.3 % females) had experienced suicide thoughts and attempted suicide, respectively. Adolescents who slept <8 hours more frequently had parents with lower educational level, lower income, psychiatric disorders, separate partners, low quality of life, higher levels of stress, and more self-harm (Table 2).

Characteristics of the weighted DNBC study population by sleep duration.

a All estimates, except absolute numbers, represent weighted estimates.

Adolescents who reported sleeping <8 hours at age 11 had higher risk of reporting suicide thoughts (aRRR, 1.7; 95 % CI, 1.3–2.01) and suicide attempt (aRRR, 3.7; 95 % CI, 2.6–5.4) at age 18 when compared with adolescents sleeping ≥9 hours in adjusted analyses (Fig. 2 and eTable 4 in Supplement). Those who slept 8 to <9 hours also had higher risk of suicide thoughts (aRRR, 1.1; 95 % CI, 1.1–1.2) and suicide attempt (aRRR, 1.3; 95 % CI: 1.1–1.6). Late bedtime, i.e. at >10:30PM, was associated with a 1.6 (95 % CI, 1.3–2.0) and 3.3 (95 % CI, 2.3–4.9) times higher risks of suicide thoughts and suicide attempt, respectively, versus going to bed at ≤9:00PM. Experiencing frequent nightmares was associated with risks of suicide thoughts of 1.4 (95 % CI, 1.3–1.5) for suicide thoughts and 2.1 (95 % CI, 1.8–2.4) for suicide attempt when compared with rarely or never experiencing nightmares.

A dose-response association was observed with respect to frequency of difficulties falling asleep. When compared to rarely or never having difficulties falling asleep, having weekly and daily difficulties were linked to aRRRs for suicide thoughts of 1.6 (95 % CI, 1.5–1.8) and 2.2 (95 % CI, 2.0–2.5), respectively. The corresponding values for suicide attempt were 1.6 (95 % CI, 1.3–2.1) for weekly and 3.6 (95 % CI, 2.9–4.5) for daily difficulties (eTable 4). A higher number of sleep disturbances was associated with elevated risks. For example, adolescents with ≥3 sleep disturbances had an aRRR of 2.9 (95 % CI, 2.1–4.1) and 9.8 (95 % CI, 6.1–15.8) for suicide thoughts and suicide attempt, respectively, when compared to those with none. Those who reported experiencing weekly difficulties with falling asleep both at age 11 and 18 had 2.9-fold (95 % CI, 2.7–3.2) and 6.7-fold (95 % CI, 5.4–8.3) higher risks of suicide thoughts and suicide attempt, respectively, versus those reporting none at either follow-up.

When adjusting for physical and mental well-being in sensitivity analysis, adolescents who slept <8 hours kept having significantly elevated risks of suicide thoughts (aRRR, 1.3; 95 % CI: 1.0–1.6) and suicide attempt (aRRR, 2.0; 95 % CI: 1.4–3.0) (Table 3). Also, adolescents who reported going to bed >10:30PM had higher risks of suicide attempt (aRRR, 1.8; 95 % CI, 1.2–2.7) than those going to bed at ≤9:00PM. When compared to adolescents who rarely or never experienced difficulties falling asleep, those with daily difficulties falling asleep were found to have an elevated risk of suicide attempt (aRRR, 1.7; 95 % CI, 1.3–2.1). Having ≥3 sleep disturbances, versus none, was significantly associated with for suicide attempt (aRRR, 2.1; 95 % CI, 1.4–3.2). In sensitivity analyses, excluding those with self-harm at baseline did not alter findings regarding suicide attempt (going to bed >10:30PM: aRRR, 1.9; 95 % CI, 1.1–3.3; ≥3 sleep disturbances: aRRR, 4.5; 95 % CI, 2.2–9.5) (eTable 5 Supplement). Further, excluding those who responded ‘do not know’ to the questions regarding suicide thoughts and suicide attempt or participants with psychiatric disorders before age 18 years did not alter most of the associations (eTable 6 Supplement and eTable 7 Supplement).

Relative risk ratiosa of suicide thoughts and suicide attempt by measures of sleep disturbances adjusted for physical and mental well-being (sensitivity analyses).

| Adjusted modelb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | No. of cases SI/SA | Suicide thoughts RRR (95 % CI) | Suicide attempt RRR (95 % CI) | |

| Sleep duration at age 11 | ||||

| <8 hours | 303 | 133/31 | 1.3 (1.0–1.6) | 2.0 (1.4–3.0) |

| 8 to <9 hours | 2768 | 974/102 | 1.0 (0.9–1.1) | 1.1 (0.9–1.3) |

| ≥9 hours | 25 180 | 7787/610 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Bedtime at age 11 | ||||

| ≤09:00PM | 16 063 | 4955/378 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| >09:00PM to 10:30PM | 11 827 | 3782/336 | 1.0 (0.9–1.0) | 1.0 (0.9–1.2) |

| >10:30PM | 361 | 157/29 | 1.2 (0.9–1.5) | 1.8 (1.2–2.7) |

| Nightmares at age 11 | ||||

| Rarely/never | 23 446 | 7053/519 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Always/sometimes | 4805 | 1841/224 | 1.2 (1.1–1.3) | 1.5 (1.2–1.7) |

| Difficulties falling asleep at age 11 | ||||

| Rarely or never | 14 561 | 3994/306 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Nearly every month | 4420 | 1422/100 | 1.1 (1.1–1.2) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) |

| More than once a month | 2785 | 929/88 | 1.2 (1.1–1.3) | 1.3 (1.1–1.7) |

| Nearly every week | 2437 | 871/76 | 1.2 (1.1–1.3) | 1.2 (0.9–1.6) |

| More than once a week | 2101 | 797/64 | 1.3 (1.1–1.4) | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) |

| Nearly every day | 1947 | 881/109 | 1.6 (1.4–1.8) | 1.7 (1.3–2.1) |

| Number of sleep disturbances at age 11 | ||||

| 0 | 20 421 | 5846/410 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| 1 | 6337 | 2394/234 | 1.1 (1.1–1.2) | 1.3 (1.1–1.6) |

| 2 | 1335 | 568/77 | 1.4 (1.2–1.5) | 1.5 (1.1–1.8) |

| ≥3 | 158 | 86/22 | 1.4 (1.2–1.8) | 2.1 (1.4–3.2) |

| Weekly difficulties falling asleep at age 11 and age 18 | ||||

| Never | 16 378 | 4079/206 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| At age 11 only | 1906 | 660/45 | 1.2 (1.1–1.4) | 1.2 (0.9–1.7) |

| At age 18 only | 7721 | 3117/359 | 2.1 (2.0–2.2) | 4.2 (3.5–5.0) |

| Both | 2122 | 1010/126 | 2.2 (2.0–2.5) | 3.7 (2.9–4.7) |

SI=suicide thoughts, SA=suicide attempt, RRR=relative risk ratio.

Based on a large cohort sample with self-reported and register-recorded measures, different sleep disturbances, i.e., low sleep duration, late bedtime, frequent nightmares, difficulties falling asleep, and cumulative number of different sleep disturbances, were associated with elevated risks of suicidality. Dose-response associations were found for adolescents who more often experienced difficulties falling asleep and those who experienced numerous forms of sleep disturbances. Increased risk of suicidality was also found among those experiencing weekly difficulties with falling asleep both at age 11 and 18. Even after adjusting for potential confounders i.e., physical, and mental well-being and excluding those with earlier psychiatric morbidity, sleep disturbances were associated with suicidal risk.

Our findings regarding a link between short sleep duration and late bedtime and suicidality adds support to existing evidence, which often has been based on Asian samples (Gong et al., 2020; Guo et al., 2021; Jeong et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2015). The measure of sleep duration was related to the time of bedtime as it was calculated from questions regarding times of going to sleep and waking up. Effect sizes for suicide thoughts and suicide attempt of respectively 1.5 and 2.4 have been reported for those sleeping <7 hours based on longitudinal data (Guo et al., 2021). Respective effect sizes between 1.7 and 1. 9 were found for those who slept <8 hours in a separate longitudinal study (Gong et al., 2020). We found similar results for suicide thoughts, but higher risk estimates for suicide attempts. Those differences might be explained by different sample sizes and study populations as well as adjusting for different covariates. Despite having a large sample size, we were unable to examine for a possible nonlinear relationship between sleep duration and the outcomes studied because there were too few observations of participants reporting sleeping <7 hours and >11 hours and experiencing suicide thoughts and suicide attempt. A systematic review and meta-analysis suggested a non-linear dose-response association between sleep duration and suicidality, indicating 8 to 9 hours as the optimal sleep duration (Chiu et al., 2018) while another review suggested that 9 hours to 9.25 hours of sleep is needed for cognitive function and emotional regulation (Crowley et al., 2018). Just a single item was used to identify nightmares. Still, the association between frequent nightmares and suicidality has previously been identified using validated scales (Liu et al., 2021; Russell et al., 2018). Experiencing difficulties falling asleep has been linked to suicide thoughts and suicide attempt among adolescents (Russell et al., 2018; Wong et al., 2016; Wong & Brower, 2012). Having self-reported data on sleep disturbances allowed us to capture the perceived experience of sleep disturbances. Nevertheless, objective measures of sleep disturbances might have improved precision and avoided risks of recall bias. Still, the existing evidence has been restricted by small samples sizes and to clinical samples of adolescents (Goetz et al., 2001; Rao et al., 1996). Among the few studies based on objective measures, the variability in sleep onsets (measured by actigraphy) was associated with an increased risk of suicide thoughts.

If sleep disturbances impair individuals’ ability to cope with negative emotions, it may play a part in developing psychiatric morbidity enhancing the risk for suicidality at a later stage. One potential mechanism connecting sleep disturbances with suicidality is that short, disturbed, and late sleep may, during sleep phases, interfere with emotional regulation (Cooper et al., 2023; Dutil et al., 2018) which in turn could increase risks of suicidality (Colmenero-Navarrete et al., 2022; Neacsiu et al., 2018). It has also been suggested that adolescents experiencing nightmares and insomnia may have higher risks of feelings of defeat and entrapment (Russell et al., 2018), which are feelings often linked to the development of suicide thoughts (O’Connor & Kirtley, 2018). Among adults, strong link between sleep disturbances, such as chronic insomnia and circadian disturbances, and major psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia and depression, have been shown (Benson, 2006; Nutt et al., 2008). This is concerning as sleep disturbances have been linked to suicidality among individuals with major psychiatric disorders (Wang et al., 2019). Our finding indicate that psychiatric comorbidity among adolescents with sleep disturbances is likely one of the driving causes for the suicidal risk such as observed in adults (Høier et al., 2022). Lastly, sleep disturbances are related to impaired cognitive functioning among children (Guerlich et al., 2024; Yang et al., 2022) and, also, individuals who tend to have late bedtimes (evening chronotypes) has been associated with impulsivity although the direction of the association is unclear (McCarthy et al., 2023). Both impaired cognitive functioning and impulsivity may contribute to an elevated risk of suicidality (Hawton et al., 2012). Still, we cannot make affirmative statements regarding a causal association.

The documented associations between sleep disturbances and suicidality underscores the need for early identification of mental health problems among adolescents who struggle with sleep. Attention towards good sleep hygiene seems indicated for young adolescents. This could, for instance, be achieved by setting up rules regarding pre-sleep screen, as use of screens during evenings has been linked to later bedtimes and shorter sleep duration (Hale et al., 2018). Implementing later meeting time in schools could be another strategy for achieving longer sleep duration and less social jetlag (Evanger et al., 2023). The Danish Health Authority has recently released new guidelines regarding sleep duration and sleep hygiene. These recommend sleep durations of 9–11 hours per day for children aged 6 to 13 years. In addition, the guidelines list eight recommendations to increase sleep duration and sleep quality. Although these recommendations were not formulated with the aim of preventing suicidality, our findings suggest that these guidelines may also have a beneficial effect on suicide thoughts and -behaviors. Cognitive behavioral therapy has also been suggested to reduce problems of insomnia in children, but it is unclear if this works on long-term (Åslund et al., 2018; Lecuelle et al., 2024; Ma et al., 2018). In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, only modest effects of sleep interventions among adults were demonstrated (Mournet & Kleiman, 2024). There is, therefore, a need for well-designed sleep interventions assessed in large and diverse samples to measure an effect with regard to suicide thoughts and suicide attempts. There is thus a significant unmet need for more evidence to ensure effective treatment for children and young people with sleep disturbances.

Strength and limitationsStrength of this study includes a large national prospective cohort. By applying inverse probability weighting, we were able to reduce selection bias. Secondly, bias by potential confounders was minimized by adjusting for a comprehensive list of register based and self-reported measures. Finally, analyzing a range of sleep disturbance measures enabled us to conduct a comprehensive and detailed assessment of the studied associations.

However, limitations also apply to this study. Firstly, objective measures of sleep disturbances, such as actigraphy for assessment of sleep duration or polysomnography for assessment of sleep patterns, were not available, still, self-reported measures offer other advantages. Secondly, suicide thoughts and suicide attempt were identified using single questions rather than validated scales, which could have either under- or overestimated associations although increased risks were documented for both outcomes. Thirdly, data on sleep measures and covariates was collected at the same time, and no data was collected during the 7 years of follow-up, thus precluding assessment of temporal relationships. Fourthly, we used the same cutoffs for bedtime and sleep duration as previously suggested (Baiden et al., 2020; Gong et al., 2020; Gunderson et al., 2023), still, other cutoffs might have resulted in different estimates. Fifthly, our measures of sleep duration and bedtime may be slightly imprecise as adolescents, for example spend time on their phones before falling asleep or experience sleep procrastination. Lastly, information on validated sleep scales, ethnicity, parental alcoholic misuse, and screen use before bedtime would have been preferred but was not available.

ConclusionIn this study, a wide range of sleep disturbances were associated with elevated risks of suicide thoughts and suicide attempt among adolescents when adjusting for a range of relevant confounders. Our findings suggested that adequate hours of sleep and earlier bedtimes might protect against suicidality in children and adolescents. Significant dose-response associations were demonstrated between difficulties falling asleep and having a higher number of sleep disturbances and suicidality, thus, emphasizing the importance of early detection and treatment of sleep disturbances among early adolescents.

Author contributionAll authors conceived and designed the study. MEM, AE, and TM were involved in the data management of the DNBC data and Danish register data. MEM conducted the analyses, supervised by TM. MEM drafted the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the analytical approach and interpretation of the data, revisions of the manuscript, and approved the final version of manuscript before submission. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted and is the guarantor of the manuscript.

Data availabilityThe data that support the findings of this study are available from Statistics Denmark and from Statens Serum Institut. Data access requires the completion of a detailed application form from the Danish Data Protection Agency, the Danish Health Data Authority and Statistics Denmark and from Statens Serum Institut. For more information on accessing the data, see https://www.dst.dk/en and https://www.dnbc.dk.

EthicsThe DNBC cohort is approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency and the Committee on Health Research Ethics under case no (KF) 01–471/94. Data handling in the DNBC has been approved by Statens Serum Institut (SSI) under ref. no 18/04,608 and is covered by the general approval (Fællesanmeldelse) given to SSI. The 11-year follow-up was approved under ref. no 2009–41–3339 and the 18-year follow-up was approved under ref. no 2015–41–3961. The DNBC participants were enrolled by informed consent. Data approval for analyses carried out in this study where DNBC data were linked with register data and accessed at Statistics Denmark’s server was obtained from Region Capital (P-2020–305).

We declare no competing interests.

The DNBC was established with a significant grant from the Danish National Research Foundation. Additional support was obtained from the Danish Regional Committees, the Pharmacy Foundation, the Egmont Foundation, the March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation, the Health Foundation and other minor grants. The follow-up of mothers and children has been supported by the Danish Medical Research Council (SSVF 0646, 271–08–0839/06–066023, O602–01042B, 0602–02738B), the Lundbeck Foundation (195/04, R100-A9193), the Innovation Fund Denmark 0603–00294B (09–067124), the Nordea Foundation (02–2013–2014), Aarhus Ideas (AU R9-A959–13-S804), a University of Copenhagen Strategic Grant (IFSV 2012) and the Danish Council for Independent Research (DFF-4183–00594 and DFF-4183–00152). The 18-year follow-up was funded by the Danish Council for Independent Research (DFF-4183–00594B; Close to Adult: 17-year follow-up of the Danish National Birth Cohort). Salary for MEM and T.M. and purchase of data for this project was granted by the Lundbeck Foundation (R344–2020–1019). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.