Prehypertension and high normal blood pressure (HNBP) are important risk factors for the development of hypertension and cardiovascular diseases. However, their prevalence in Latin America has not been systematically evaluated.

ObjectivesTo determine the prevalence of prehypertension and HNBP in Latin America through a systematic review and meta-analysis.

MethodsA systematic search was conducted in electronic databases until September 24, 2024. Observational studies with probabilistic sampling that reported the prevalence of prehypertension or HNBP in adult Latin American populations were included. Random-effects models were used for the meta-analysis, and subgroup analyses and meta-regression were performed.

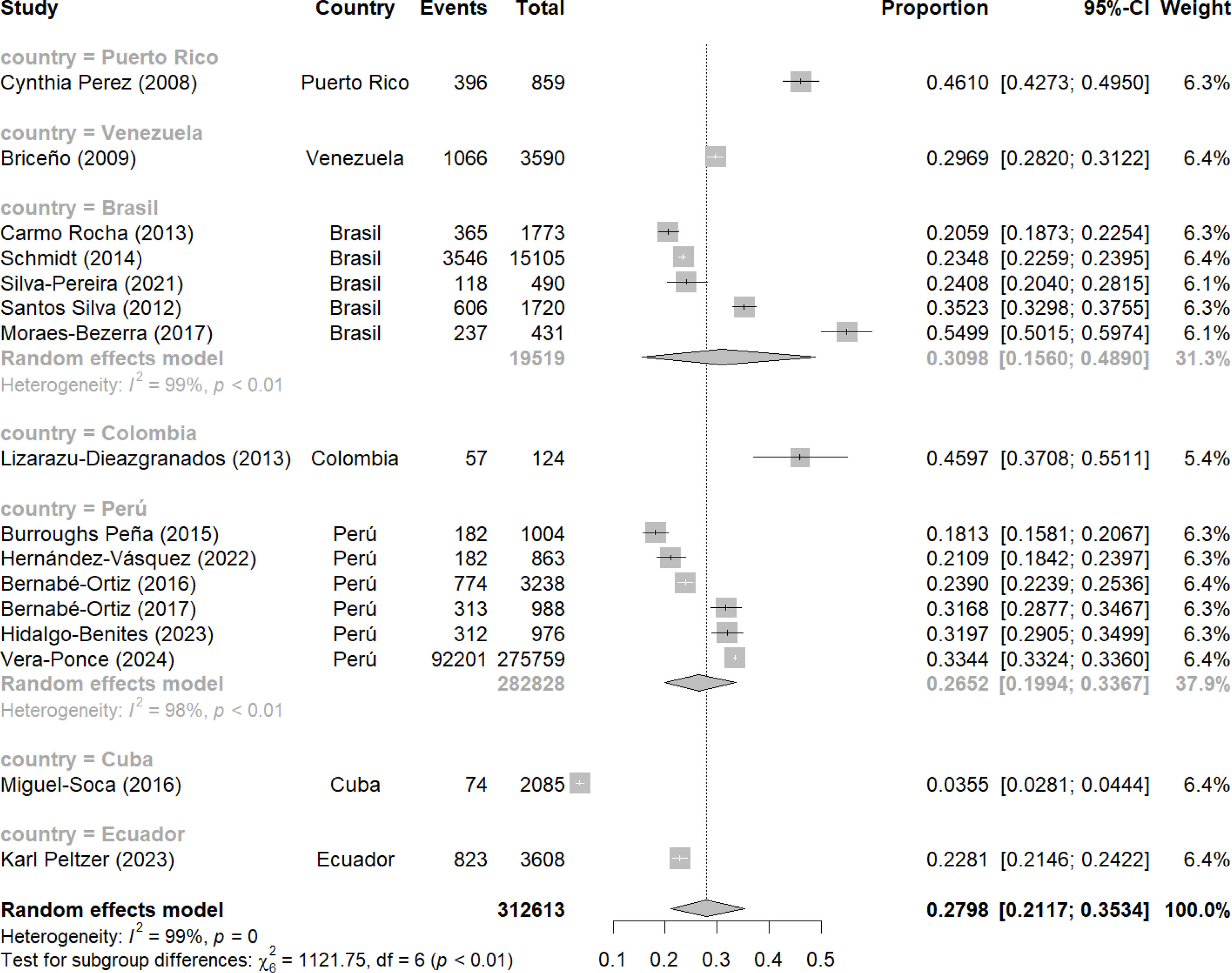

ResultsA total of 17 studies (n=227,741) from 7 countries were included. The pooled prevalence of prehypertension was 27.98% (95% CI: 21.17–35.34%), with significant heterogeneity (I2=100%, p<0.01). The prevalence of HNBP was 19.23% (95% CI: 11.43–28.49%). Considerable variations were observed between countries, with prehypertension prevalence ranging from 3.55% in Cuba to 46.10% in Puerto Rico. Meta-regression analyses identified a slight decreasing trend in prehypertension prevalence over time and with increasing sample size.

ConclusionThis study reveals a high prevalence of prehypertension and HNBP in Latin America, with significant variations between countries. These findings underscore the need for tailored public health strategies to prevent and manage these prehypertensive states early in the region.

La prehipertensión y la presión arterial normal elevada (PAHA) son factores de riesgo importantes para el desarrollo de hipertensión y enfermedades cardiovasculares. Sin embargo, su prevalencia en América Latina no ha sido evaluada sistemáticamente.

ObjetivosDeterminar la prevalencia de prehipertensión y PAHA en América Latina mediante una revisión sistemática y metaanálisis.

MétodosSe realizó una búsqueda sistemática en bases de datos electrónicas hasta el 24 de septiembre de 2024. Se incluyeron estudios observacionales con muestreo probabilístico que reportaran la prevalencia de prehipertensión o PAHA en poblaciones adultas latinoamericanas. Para el metaanálisis se utilizaron modelos de efectos aleatorios y se realizaron análisis de subgrupos y metarregresión.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 17 estudios (n=227.741) de 7 países. La prevalencia combinada de prehipertensión fue del 27,98% (IC 95%: 21,17%-35,34%), con heterogeneidad significativa (I2=100%, p<0,01). La prevalencia de PAHA fue del 19,23% (IC 95%: 11,43%-28,49%). Se observaron variaciones considerables entre países, con una prevalencia de prehipertensión que osciló entre el 3,55% en Cuba y el 46,10% en Puerto Rico. Los análisis de metarregresión identificaron una ligera tendencia decreciente en la prevalencia de prehipertensión a lo largo del tiempo y con el aumento del tamaño de la muestra.

ConclusiónEste estudio revela una alta prevalencia de prehipertensión y PAHA en América Latina, con variaciones significativas entre países. Estos hallazgos subrayan la necesidad de estrategias de salud pública personalizadas para prevenir y controlar estos estados prehipertensivos de forma temprana en la región.

Arterial hypertension is a global public health concern, considered one of the main modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular diseases. In recent decades, particular attention has been paid to the stages preceding hypertension development, known as prehypertension and high-normal blood pressure (HNBP). These conditions are associated with an increased risk of progression to hypertension and elevated cardiovascular morbidity.1

While the concept of prehypertension was introduced by the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee 7 (JNC 7),2 and guidelines subsequently proposed the term high-normal blood pressure,3,4 it is crucial to recognize that the relationship between blood pressure and cardiovascular risk is continuous. Epidemiological studies have demonstrated that the risk of developing cardiovascular disease begins to increase from blood pressure levels as low as 120/80mmHg.5 For instance, the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) demonstrated benefits in reducing cardiovascular events with more intensive blood pressure control, even in individuals without established hypertension.6 These findings underscore the importance of considering the complete spectrum of blood pressure, including levels previously considered “normal,” in cardiovascular risk assessment and prevention strategies.

In Latin America, the burden of cardiovascular diseases has increased significantly in recent decades, partly due to epidemiological transition and lifestyle changes. However, the prevalence of prehypertension and high-normal blood pressure in this region has not been systematically evaluated, hindering the implementation of effective prevention strategies.7 Furthermore, although individual studies have suggested a considerable prevalence of prehypertension and HNBP in Latin American countries, studies evaluating the overall prevalence in the region are scarce.8–11 This lack of comprehensive regional data is further complicated by methodological heterogeneity among existing studies. Variations include differences in the definition used (prehypertension vs. high-normal blood pressure), blood pressure measurement methods (e.g., office measurements vs. ambulatory monitoring), and characteristics of the studied populations. Additionally, it remains unclear whether available studies focus more on which of the two pre-hypertension definitions, making it difficult to compare and obtain a coherent view of the situation in the region.

Given the importance of understanding the magnitude of this problem in the region, the present study sought to conduct a systematic review (SR) with meta-analysis synthesizing the available evidence on the prevalence of prehypertension and HNBP in Latin America. This information is fundamental for informing public health policies, designing prevention strategies, and promoting early detection and appropriate management of these cardiovascular risk states in the Latin American population.

MethodsStudy designThis research was conducted as an SR with meta-analysis, focusing on cross-sectional studies carried out in Latin America. The methodology strictly adhered to the guidelines established by the PRISMA statement (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement,12 with necessary adaptations for a systematic review centered on prevalence studies. This approach ensures a rigorous and transparent synthesis of available evidence on the prevalence of prehypertension and high-normal blood pressure in the Latin American region.

Search strategyA comprehensive search was conducted across four academic databases: Scopus, Web of Science, Embase, and PubMed/Medline until September 24, 2024. Key search terms included: “prevalence,” “prehypertension,” “pre-hypertension,” “high normal blood pressure,” “elevated blood pressure,” and “Latin America” or specific Latin American country names. The detailed search strategy for each database is provided in Supplementary Material 1.

Each strategy was meticulously adapted for each database, employing controlled vocabulary (such as MeSH terms in PubMed) when available, in combination with free-text searching. Publications in English, Spanish, and Portuguese were included, with no restrictions on publication year to ensure complete coverage of relevant literature.

To complement the electronic search, manual searches were conducted in the reference lists of included articles and relevant previous systematic reviews. This approach allowed for the identification of additional studies that might have been overlooked in the initial electronic search.

Selection criteriaStudies were considered eligible for inclusion if they met the following specific criteria: (1) cross-sectional observational studies published as full articles, focusing on evaluating the prevalence of prehypertension and/or high-normal blood pressure; (2) studies had to include adult participants (≥18 years) of both sexes, residing in Latin American countries; (3) studies had to assess prevalence using systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) measurements. The definition of prehypertension had to follow JNC 7 criteria (SBP of 120–139mmHg or DBP of 80–89mmHg),2 while HNBP had to conform to European guidelines (SBP of 130–139mmHg and/or DBP of 85–89mmHg); (4) probabilistic sampling methods were required, including simple random, stratified, cluster, or multistage sampling; (5) studies had to provide sufficient data to calculate the prevalence of prehypertension and/or high-normal blood pressure, or directly report these measures with their respective confidence intervals; and (6) studies published in English, Spanish, or Portuguese were considered.

Conversely, the following were excluded: (1) narrative reviews, editorials, letters to the editor, commentaries, and case studies; (2) studies using non-probabilistic sampling methods; (3) research focused exclusively on populations with specific medical conditions, such as hospitalized patients or individuals with pre-existing cardiovascular diseases; (4) studies not providing original data, such as predictive models based on secondary data; and (5) preclinical or animal studies.

Study selection processRayyan software (https://rayyan.qcri.org) was used to manage and store articles identified in the databases. This tool facilitated the organization and tracking of studies throughout the selection process.

Study selection was conducted in two phases. First, two independent reviewers examined the titles and abstracts of identified manuscripts. This phase was conducted blindly to minimize bias. Studies that both reviewers considered to meet inclusion criteria were selected for detailed review. In case of disagreement, a third reviewer intervened as arbitrator to resolve the discrepancy. Subsequently, full-text review was conducted, where a comprehensive evaluation of the complete text of all preselected articles was performed. Two reviewers carried out this process independently, following the same protocol as the initial phase. An Excel spreadsheet was used to record inclusion or exclusion decisions, along with specific reasons for exclusion when applicable. Discrepancies at this stage were resolved through discussion between reviewers, and in cases of lack of consensus, a fourth reviewer was consulted for the final decision.

To ensure comprehensive selection, an additional manual search was conducted in the reference lists of included articles and previous systematic reviews on related topics. Studies identified through this method underwent the same selection process described above.

In cases of multiple publications based on the same study population, the most recent article or the one providing more complete information on the prevalence of prehypertension and/or high-normal blood pressure was included.

The entire selection process was meticulously documented, including the number of studies identified, screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the review, along with reasons for exclusion at each stage.

Data extraction and qualitative analysisData extraction was performed using a Microsoft Excel 2023 template specifically designed for this systematic review. Two independent reviewers conducted this process to ensure accuracy and comprehensiveness of extracted data. The template was piloted with a sample of included studies to ensure its suitability before complete extraction.

Extracted data encompassed detailed information about study characteristics and their results, including: author(s) and publication year, Latin American country(ies) involved, study design and data collection period, sample size and demographic characteristics (age, sex), probabilistic sampling method used, diagnostic criteria employed for prehypertension and/or high-normal blood pressure, blood pressure measurement method (device, number of measurements), reported prevalence of prehypertension and/or HNBP.

Discrepancies in data extraction or qualitative interpretation between the two reviewers were resolved through discussion and consensus. In cases of persistent disagreement, a third reviewer was consulted for the final decision.

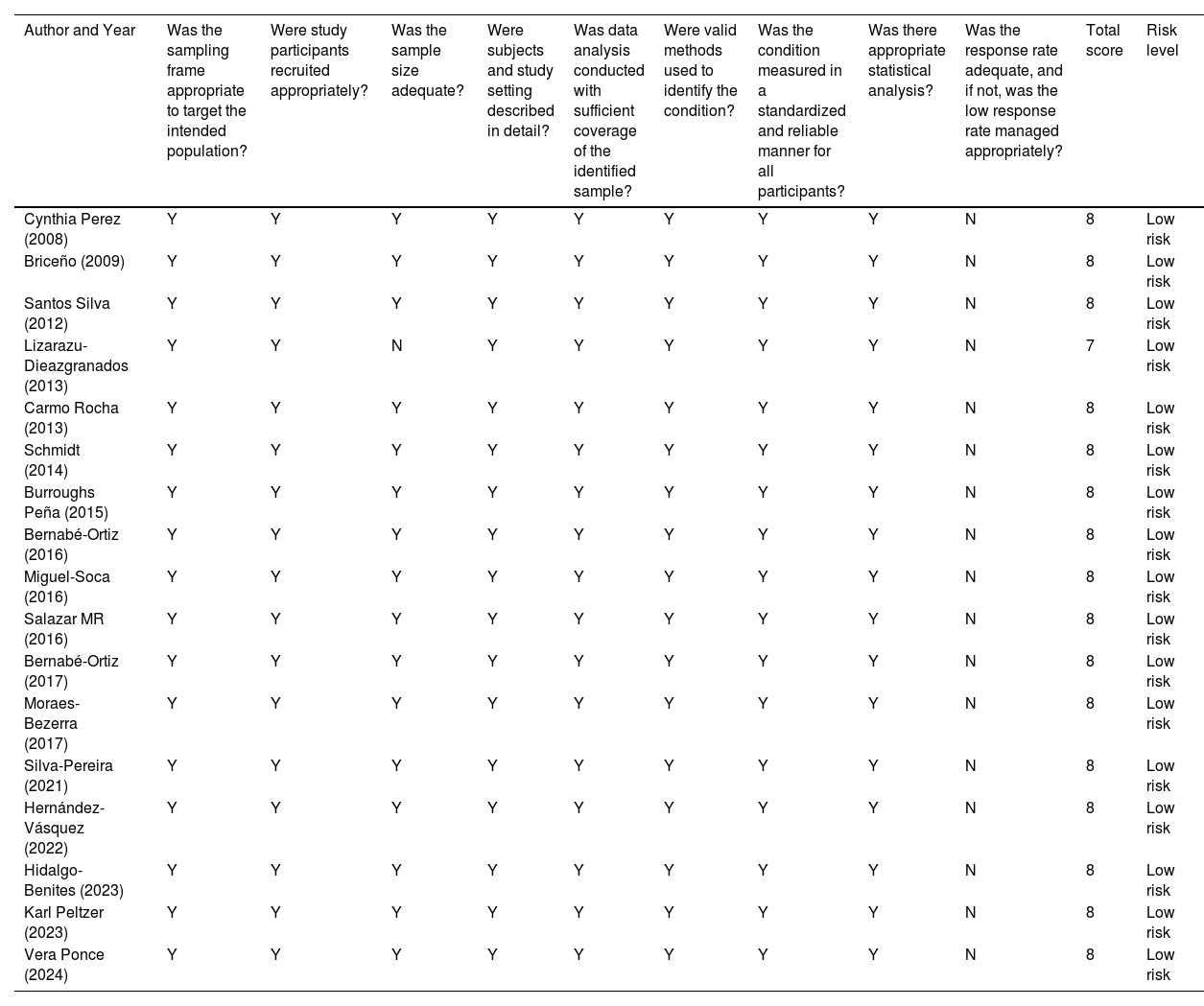

Risk of bias assessmentRisk of bias assessment was conducted independently by two investigators for all studies included in the systematic review. For this purpose, Munn et al.’s risk of bias assessment tool,13 specifically designed for prevalence studies, was used. This tool was selected due to its suitability for evaluating the methodological quality of prevalence studies and its wide acceptance in the field of systematic reviews.

The assessment was based on ten specific criteria covering key aspects of prevalence study methodology. These criteria include sample representativeness of the target population, appropriateness of the sampling frame, random selection process of participants, minimization of non-response bias, data collection directly from subjects, case definition acceptability, study instrument reliability and validity, consistency in data collection mode, appropriateness of shortest prevalence period length, and appropriateness of the denominator.

For each criterion, reviewers assigned a response of “Low risk,” “High risk,” or “Unclear.” A total score was calculated for each study, awarding one point for each “Low risk” response. The level of risk of bias was categorized as follows: studies with 0–3 points were considered high risk, 4–6 points medium risk, and 7–10 points low risk of bias.

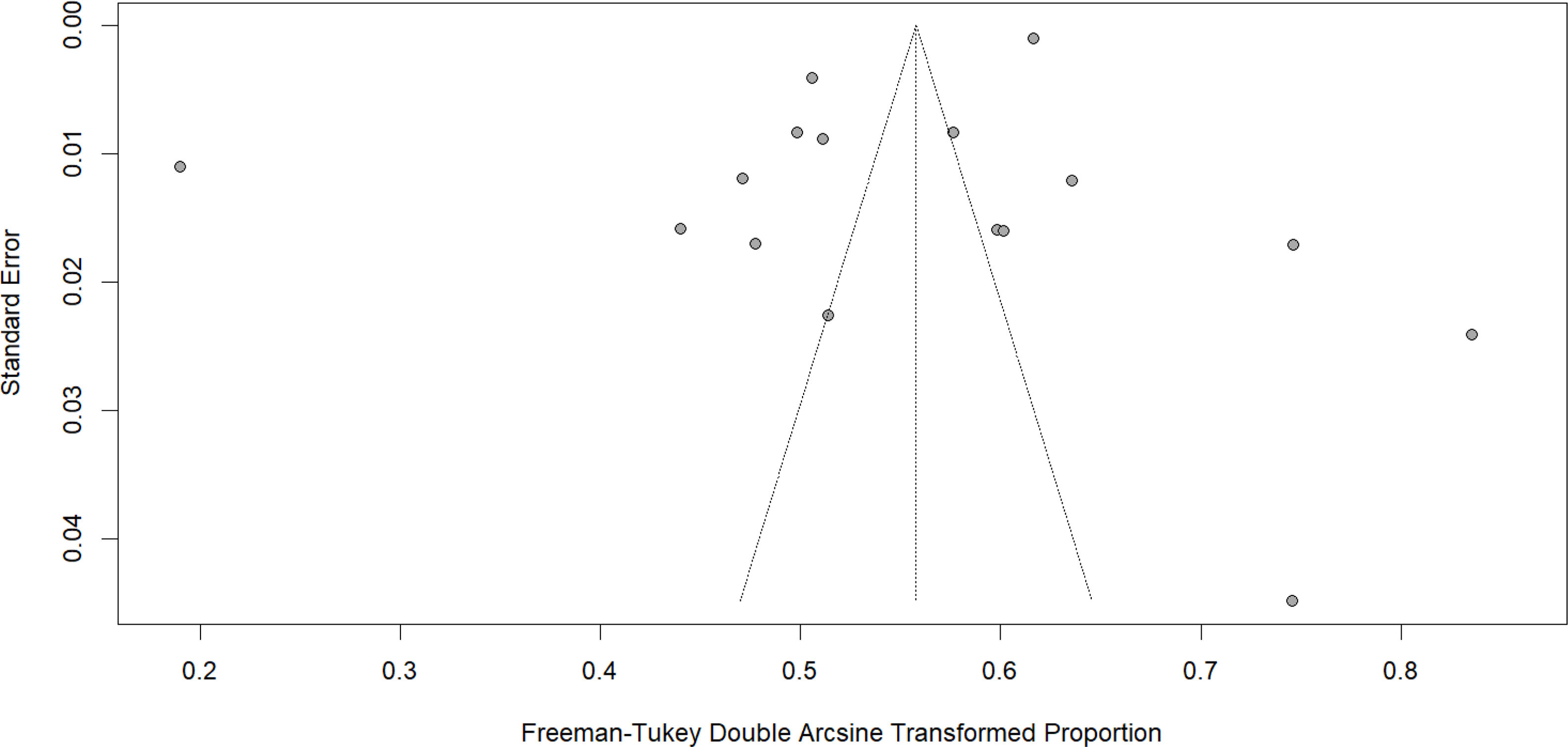

Additionally, publication bias was assessed through visual inspection of funnel plots and application of Egger's test, when appropriate. These assessments were conducted to determine if there was evidence of bias in the literature included in the systematic review.

Statistical analysisAll quantitative analyses were performed using R statistical software version 4.2.2. For the meta-analysis, all studies providing data on the prevalence of prehypertension and/or HNBP, assessed through systolic and diastolic blood pressure measurements, were included. Both total sample size (n) and number of cases (r) were extracted for each study.

The meta-analysis was conducted using the ‘metaprop’ function from the ‘meta’ package. The Freeman–Tukey double arcsine transformation method (sm=“PFT”) was employed for proportion transformation. Confidence intervals were calculated using the Clopper–Pearson method (method.ci=“CP”), which provides exact confidence intervals for proportions.

Given the expectation of significant variability due to differences in study populations, blood pressure measurement methods, and other contextual factors across Latin American countries, a random-effects model with the DerSimonian and Laird method (method.tau=“DL”) was used to estimate between-study heterogeneity. The Hartung–Knapp correction (hakn=TRUE) was applied to adjust standard errors. Additionally, heterogeneity between studies was assessed using the I2 statistic and Cochran's Q test, which are automatically calculated in the ‘metaprop’ function. Thus, meta-analysis results were presented with their respective 95% confidence intervals and visualized through forest plots using the ‘forest’ function from the ‘meta’ package.

Additionally, meta-regressions were conducted to examine the influence of continuous variables on prevalence estimates, specifically publication year and sample size. The weighted least squares method was used, with weights inversely proportional to each study's variance. For each meta-regression, a mixed-effects model was fitted using the “rma” function from the “metafor” package in R. To visualize the results, bubble plots were generated where the size of each bubble is proportional to the study's weight in the analysis.

Ethical considerationsThis systematic review and meta-analysis was based exclusively on the analysis of aggregated data from previously published studies on the prevalence of prehypertension and HNBP in the region. This methodological approach did not involve the collection of individual participant data or the conduct of new interventions or experiments. Consequently, specific ethical approval was not required for the execution of this synthesis study.

ResultsEligible studiesA total of 1108 publications were found. After removing duplicates (760), 348 manuscripts were analyzed based on title and abstract. After excluding 322 studies, 26 full articles were obtained. Finally, after applying the selection criteria, 17 articles were selected.8,10,14–28 The process can be visualized in Fig. 1.

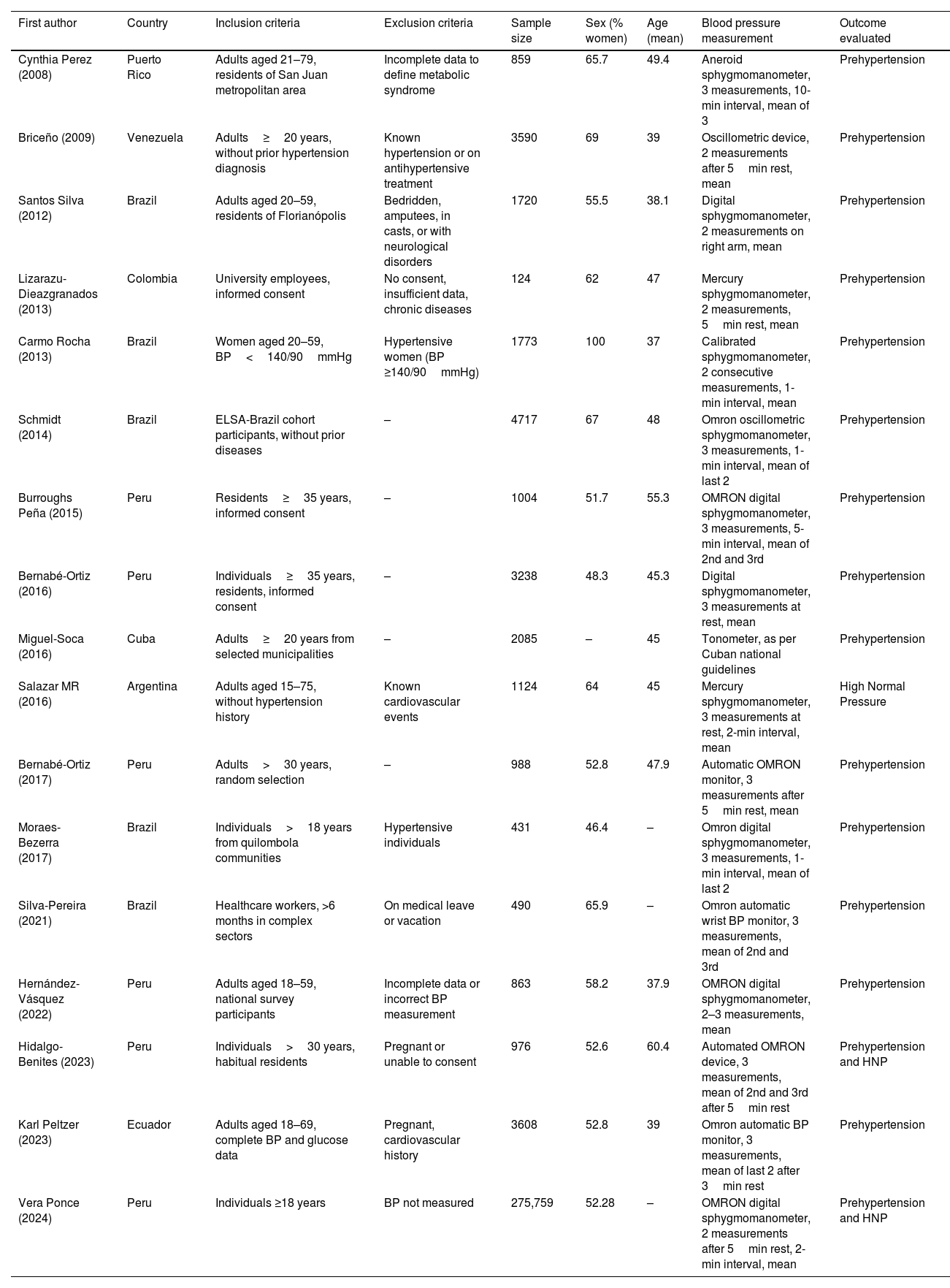

Study characteristicsTable 1 presents a summary of the characteristics of studies included in this SR. Of these, 15 studies focused on evaluating prehypertension, one focused exclusively on HNBP, and one study addressed both conditions. This distribution underscores the predominant interest of the scientific community in prehypertension within the Latin American context.

Characteristics of the selected studies.

| First author | Country | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | Sample size | Sex (% women) | Age (mean) | Blood pressure measurement | Outcome evaluated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cynthia Perez (2008) | Puerto Rico | Adults aged 21–79, residents of San Juan metropolitan area | Incomplete data to define metabolic syndrome | 859 | 65.7 | 49.4 | Aneroid sphygmomanometer, 3 measurements, 10-min interval, mean of 3 | Prehypertension |

| Briceño (2009) | Venezuela | Adults≥20 years, without prior hypertension diagnosis | Known hypertension or on antihypertensive treatment | 3590 | 69 | 39 | Oscillometric device, 2 measurements after 5min rest, mean | Prehypertension |

| Santos Silva (2012) | Brazil | Adults aged 20–59, residents of Florianópolis | Bedridden, amputees, in casts, or with neurological disorders | 1720 | 55.5 | 38.1 | Digital sphygmomanometer, 2 measurements on right arm, mean | Prehypertension |

| Lizarazu-Dieazgranados (2013) | Colombia | University employees, informed consent | No consent, insufficient data, chronic diseases | 124 | 62 | 47 | Mercury sphygmomanometer, 2 measurements, 5min rest, mean | Prehypertension |

| Carmo Rocha (2013) | Brazil | Women aged 20–59, BP<140/90mmHg | Hypertensive women (BP ≥140/90mmHg) | 1773 | 100 | 37 | Calibrated sphygmomanometer, 2 consecutive measurements, 1-min interval, mean | Prehypertension |

| Schmidt (2014) | Brazil | ELSA-Brazil cohort participants, without prior diseases | – | 4717 | 67 | 48 | Omron oscillometric sphygmomanometer, 3 measurements, 1-min interval, mean of last 2 | Prehypertension |

| Burroughs Peña (2015) | Peru | Residents≥35 years, informed consent | – | 1004 | 51.7 | 55.3 | OMRON digital sphygmomanometer, 3 measurements, 5-min interval, mean of 2nd and 3rd | Prehypertension |

| Bernabé-Ortiz (2016) | Peru | Individuals≥35 years, residents, informed consent | – | 3238 | 48.3 | 45.3 | Digital sphygmomanometer, 3 measurements at rest, mean | Prehypertension |

| Miguel-Soca (2016) | Cuba | Adults≥20 years from selected municipalities | – | 2085 | – | 45 | Tonometer, as per Cuban national guidelines | Prehypertension |

| Salazar MR (2016) | Argentina | Adults aged 15–75, without hypertension history | Known cardiovascular events | 1124 | 64 | 45 | Mercury sphygmomanometer, 3 measurements at rest, 2-min interval, mean | High Normal Pressure |

| Bernabé-Ortiz (2017) | Peru | Adults>30 years, random selection | – | 988 | 52.8 | 47.9 | Automatic OMRON monitor, 3 measurements after 5min rest, mean | Prehypertension |

| Moraes-Bezerra (2017) | Brazil | Individuals>18 years from quilombola communities | Hypertensive individuals | 431 | 46.4 | – | Omron digital sphygmomanometer, 3 measurements, 1-min interval, mean of last 2 | Prehypertension |

| Silva-Pereira (2021) | Brazil | Healthcare workers, >6 months in complex sectors | On medical leave or vacation | 490 | 65.9 | – | Omron automatic wrist BP monitor, 3 measurements, mean of 2nd and 3rd | Prehypertension |

| Hernández-Vásquez (2022) | Peru | Adults aged 18–59, national survey participants | Incomplete data or incorrect BP measurement | 863 | 58.2 | 37.9 | OMRON digital sphygmomanometer, 2–3 measurements, mean | Prehypertension |

| Hidalgo-Benites (2023) | Peru | Individuals>30 years, habitual residents | Pregnant or unable to consent | 976 | 52.6 | 60.4 | Automated OMRON device, 3 measurements, mean of 2nd and 3rd after 5min rest | Prehypertension and HNP |

| Karl Peltzer (2023) | Ecuador | Adults aged 18–69, complete BP and glucose data | Pregnant, cardiovascular history | 3608 | 52.8 | 39 | Omron automatic BP monitor, 3 measurements, mean of last 2 after 3min rest | Prehypertension |

| Vera Ponce (2024) | Peru | Individuals ≥18 years | BP not measured | 275,759 | 52.28 | – | OMRON digital sphygmomanometer, 2 measurements after 5min rest, 2-min interval, mean | Prehypertension and HNP |

The temporal spectrum of analyzed studies spans more than a decade and a half of research, providing a valuable longitudinal view of the field. The oldest study, conducted by Cynthia Pérez14 in 2008 in Puerto Rico, marks the beginning of this research period. At the most recent end, we find several studies conducted in 2023, including those by Hidalgo-Benites,26 and Karl Peltzer,27 along with a study by Vera-Ponce dated 2024.28

Regarding sample sizes, considerable variability is observed, reflecting different research approaches and resources. The most extensive study, conducted by Vera-Ponce in 2024 in Peru, included a sample of 275,759 participants.28 At the other end of the spectrum, Lizarazu-Dieazgranados's 2013 study in Colombia worked with a sample of 124 participants.17

Gender representation in the studies shows variations. While most studies included both men and women, Carmo Rocha's 2013 study18 in Brazil stands out for focusing exclusively on women, with a 100% female sample. In contrast, Moraes-Bezerra's 2017 study23 in Brazil presented the lowest proportion of women, at 46.4%.

In terms of geographical distribution, Peru is the most represented country in this review, with six studies,8,22,25,26,28 followed closely by Brazil with five.16,18,19,23,24 In contrast, countries such as Cuba, Puerto Rico, Argentina, Venezuela, and Ecuador are represented by only one study each.

The selection criteria of the studies show some notable similarities. Most focused on adult populations, generally defined as individuals over 18 years, although Salazar MR's study included participants from age 15.10 At the other extreme, Hidalgo-Benites's 2023 study in Peru focused on an older population, with an average age of 60.4 years.26 Additionally, a common exclusion criterion among selected studies was the presence of previously diagnosed hypertension or use of antihypertensive medications, allowing a more precise focus on prehypertension and HNBP. Several studies also excluded individuals with pre-existing cardiovascular diseases or conditions that could affect blood pressure measurements.

Finally, regarding blood pressure measurement methods, general consistency is observed in the use of automatic digital devices, with a notable preference for OMRON brand equipment. Most studies performed multiple measurements, typically two or three, and used their average for analyses, increasing measurement reliability. However, some variations in specific protocols were noted. Some studies, such as those by Cynthia Perez14 and Salazar MR,10 opted for mercury or aneroid sphygmomanometers, possibly reflecting more traditional clinical practices or resource limitations. There were differences in rest times before measurements (varying from 5 to 15min) and in intervals between measurements (from 1 to 10min).

Regarding bias analysis, evaluated in Table 2, of the 17 studies evaluated, all obtained scores of 8, except for Lizarazu-Dieazgranados's study (2013),17 due to the small sample size presented. Thus, all were classified in the low risk of bias category.

Bias analysis of the selected studies.

| Author and Year | Was the sampling frame appropriate to target the intended population? | Were study participants recruited appropriately? | Was the sample size adequate? | Were subjects and study setting described in detail? | Was data analysis conducted with sufficient coverage of the identified sample? | Were valid methods used to identify the condition? | Was the condition measured in a standardized and reliable manner for all participants? | Was there appropriate statistical analysis? | Was the response rate adequate, and if not, was the low response rate managed appropriately? | Total score | Risk level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cynthia Perez (2008) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 8 | Low risk |

| Briceño (2009) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 8 | Low risk |

| Santos Silva (2012) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 8 | Low risk |

| Lizarazu-Dieazgranados (2013) | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 7 | Low risk |

| Carmo Rocha (2013) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 8 | Low risk |

| Schmidt (2014) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 8 | Low risk |

| Burroughs Peña (2015) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 8 | Low risk |

| Bernabé-Ortiz (2016) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 8 | Low risk |

| Miguel-Soca (2016) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 8 | Low risk |

| Salazar MR (2016) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 8 | Low risk |

| Bernabé-Ortiz (2017) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 8 | Low risk |

| Moraes-Bezerra (2017) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 8 | Low risk |

| Silva-Pereira (2021) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 8 | Low risk |

| Hernández-Vásquez (2022) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 8 | Low risk |

| Hidalgo-Benites (2023) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 8 | Low risk |

| Karl Peltzer (2023) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 8 | Low risk |

| Vera Ponce (2024) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 8 | Low risk |

Y=yes; N=no; U=unclear.

According to the random-effects model, the combined prevalence of prehypertension in Latin America is estimated at 27.98% (95% CI: 21.17–35.34%). However, heterogeneity was very high (I2=100%, p<0.01).

When examining results by country, different patterns are observed. Brazil, for example, shows a wide range of estimates, oscillating between 20.59% and 54.99%, with a combined estimate of 30.72% (95% CI: 15.16–48.96%). Peru presents a similar panorama, with prevalences ranging from 18.13% to 33.44%, and a combined estimate of 28.39% (95% CI: 18.64–39.29%).

Some countries stand out for their extreme values. Puerto Rico, represented by Cynthia Perez's study (2008),14 shows the highest individual prevalence at 46.10% (95% CI: 42.73–49.50%). At the other extreme, Cuba, with Miguel-Soca's study (2016),21 presents the lowest prevalence at 3.55% (95% CI: 2.81–4.44%). Meanwhile, the other countries included in the analysis, Venezuela, Colombia, and Ecuador show prevalences of 29.69%, 45.97%, and 22.81% respectively.

Meta-analysis of high-normal blood pressure prevalenceAccording to the random-effects model, the combined prevalence of HNBP in these countries is estimated at 19.23% (95% CI: 11.43–28.49%). Individually, Salazar MR's study (2016)10 in Argentina shows the highest HNBP prevalence at 23.47% (95% CI: 21.02–26.06%). Meanwhile, in Peru, two studies are included. Hidalgo-Benites's study (2023)26 shows a prevalence of 16.70% (95% CI: 14.41–19.19%), while Vera-Ponce's study (2024)28 indicates a slightly higher prevalence of 17.96% (95% CI: 17.81–18.10%). However, heterogeneity between studies is considerable (I2=91%, p<0.01).

Funnel plot analysisThe distribution of points in the plot exhibits noticeable asymmetry, deviating from the ideal inverted funnel shape that would be expected in the absence of bias. This asymmetry, along with the considerable dispersion of points, especially at the lower part of the plot, suggests the presence of significant heterogeneity among the studies included. The existence of some points clearly separated from the main cluster, particularly on the right side, indicates the presence of studies with unusual or extreme results that warrant special attention. Furthermore, the clustering of several studies at the top of the plot suggests that some high-precision studies, likely with large sample sizes, yield similar effect estimates (Figs. 2 and 3).

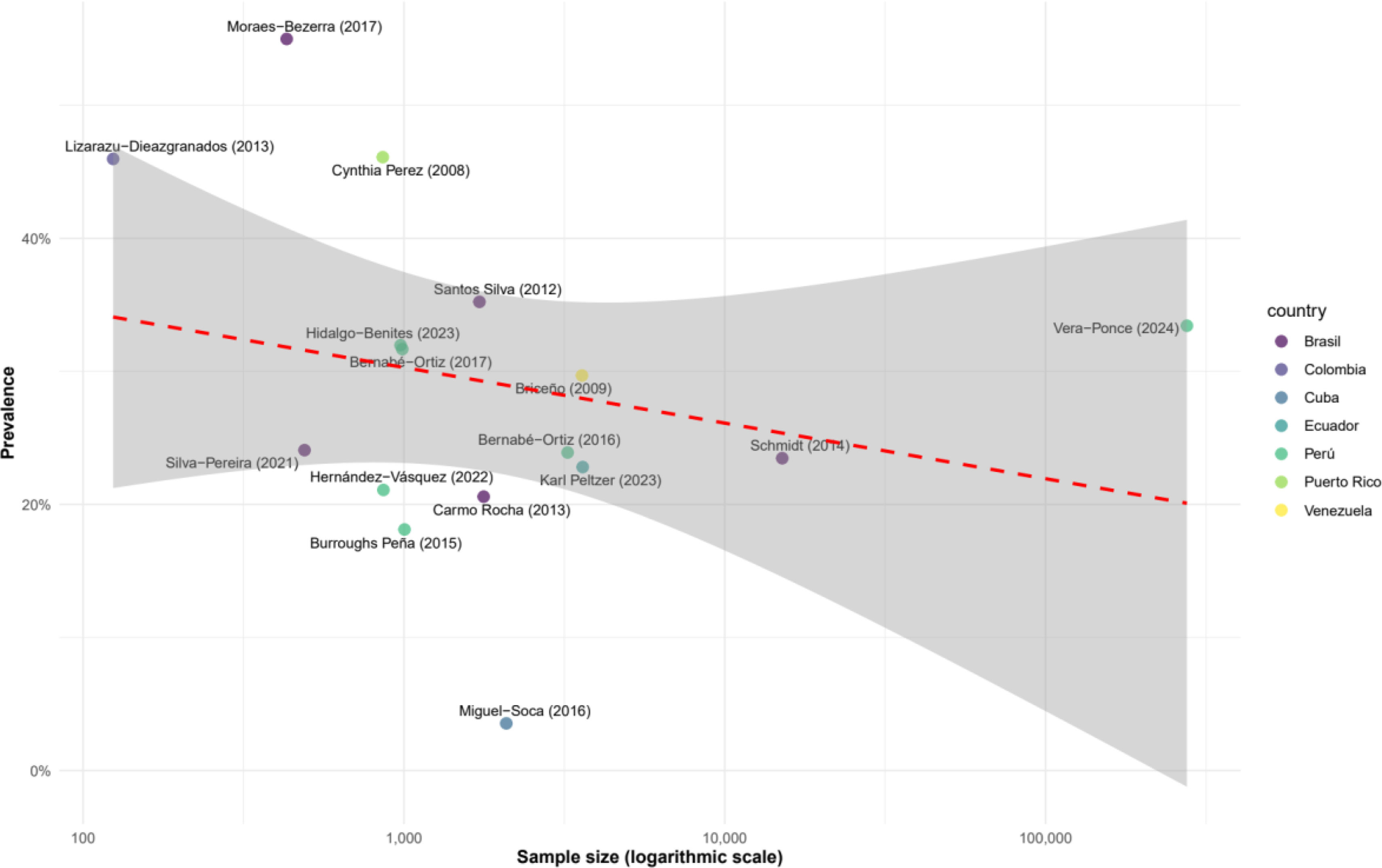

Meta-regression analysis of prehypertensionFig. 4 illustrates the relationship between the year of publication and the prevalence of prehypertension across various studies conducted in Latin American countries. This bubble plot shows a slightly decreasing trend in prehypertension prevalence over time, as indicated by the red dashed regression line. However, the wide gray band surrounding this line suggests considerable uncertainty in this trend. The studies are represented by circles whose size reflects the sample size, and the colors indicate different countries. A large variability in the reported prevalence is observed, ranging from less than 10% to over 50%.

Fig. 5 illustrates the relationship between sample size (on a logarithmic scale) and the prevalence of prehypertension across various studies conducted in Latin American countries. The red dashed line represents the overall trend, showing a slight decrease in prevalence as sample size increases. However, the wide shaded gray area around this line indicates considerable uncertainty in this trend. The studies are represented by points of different colors based on the country, allowing for easy comparison between nations.

DiscussionMain findingsIn this meta-analysis of Latin American studies, we found a combined prevalence of prehypertension of 27.98% (95% CI: 21.17–35.34%), indicating that more than a quarter of the adult population in the region might be at elevated risk of developing hypertension. The prevalence of HNBP was estimated at 19.23% (95% CI: 11.43–28.49%), although this estimate is based on a more limited number of studies. We observed considerable heterogeneity among countries, with prehypertension prevalences ranging from 3.55% in Cuba to 46.10% in Puerto Rico. Meta-regression analyses suggested a slight decreasing trend in prehypertension prevalence over time and with increasing sample size, although these trends were accompanied by substantial uncertainty. These findings underscore the significant magnitude of prehypertension and HNBP in Latin America while revealing important variations between countries that warrant further investigation.

Interpretation of our resultsIn interpreting our results, it is crucial to contextualize our findings with existing literature on prehypertension and HNBP at global and regional levels. Our combined prevalence estimates of 28.76% for prehypertension in the region is comparable with findings from other international studies. For instance, a global meta-analysis conducted by Guo et al. found a worldwide prehypertension prevalence of 36% (95% CI: 31.0–41.2%).29 Our results suggest that prevalence in Latin America might be slightly lower than these global averages, although the heterogeneity observed between countries indicates that some nations in the region may be close to or even exceed these figures.

The significant variability we found among Latin American countries is consistent with findings from previous studies that have examined regional differences in cardiovascular risk factors. For example, Chow et al.’s PURE study highlighted important differences in hypertension prevalence among low- and middle-income countries, with ranges from 32.5% to 40.8% across different regions.30 Our findings of prehypertension prevalences ranging from 3.55% in Cuba to 46.10% in Puerto Rico reflect even greater variability, underscoring the importance of considering country-specific factors when interpreting these data.

Regarding HNBP, our estimate of 19.23% aligns with findings from European studies, although it is important to note that literature on HNBP is less abundant than that on prehypertension. Additionally, it is noteworthy that more studies with probabilistic sampling have been conducted on prehypertension than on HNBP, likely because the definition of the latter is recent.3 Mancia et al. reported an HNBP prevalence of 13.5% in an Italian cohort,31 while the PAMELA study found a prevalence of 11.6% in another Italian population.32 Our results suggest that HNBP prevalence in Latin America might be slightly higher than these European estimates, although the limited number of studies included in our HNBP analysis indicates the need for more research in this specific area in the Latin American context.

The slightly decreasing trend in prehypertension prevalence over time observed in our meta-regression analysis is an interesting finding that deserves further exploration. This trend might reflect improvements in public health strategies and increased awareness about the importance of blood pressure control in the region. However, it contrasts with findings from some longitudinal studies such as Vasan et al., who observed an increase in hypertension incidence over time in individuals with prehypertension.33 This apparent discrepancy might be due to differences in study designs, examined populations, or time periods considered.

The variations observed in prehypertension and HNBP prevalence among Latin American countries can be attributed to a series of complex and interrelated factors. First, differences in lifestyles and dietary habits play a crucial role. A study by Carrillo-Larco and Bernabe-Ortiz34 reported that salt consumption in Latin America was more than double that recommended by the World Health Organization. Similarly, Bernabé-Ortiz et al.8 reported in Peru that excessive alcohol consumption and physical inactivity, especially in urban areas, were important risk factors for prehypertension or HNBP.

Socioeconomic disparities may also explain part of the observed variability. Chambergo-Michilot et al. demonstrated in Mexico that hypertension prevalence was lower in higher socioeconomic groups.35 This pattern might be extrapolated to other countries in the region, where economic inequalities are pronounced. Furthermore, access to health services and their quality vary significantly between and within Latin American countries, as pointed out by Atun et al. in their analysis of the region's health systems.36

Genetic and ethnic factors may also contribute to the observed differences. A study by Quaresma et al. in Brazil found variations in prehypertension prevalence among different ethnic groups, with higher rates in Afro-descendant populations.37 These genetic differences may interact with environmental factors, resulting in variations in susceptibility to prehypertension and HNBP.

Urbanization and associated changes in physical activity patterns may also explain part of the variability. Miranda et al. observed in Peru that migration from rural to urban areas was associated with an increase in cardiovascular risk factors, which may include prehypertension.38 This phenomenon might be occurring to different degrees across countries in the region.

Finally, methodological differences between studies, such as sample selection criteria, blood pressure measurement methods, and operational definitions of prehypertension and HNBP, may contribute to the observed variability. For instance, Hernández-Vásquez et al. noted that the choice of measurement device and protocol followed can significantly influence prevalence estimates.39

Public health implicationsFirst, the combined high prevalence of prehypertension (28.76%) suggests that a substantial proportion of the Latin American population is at elevated risk of developing hypertension and its associated complications. This aligns with projections by Olsen et al., who anticipated a significant increase in the cardiovascular disease burden in the region over the coming decades.40 Therefore, it is imperative that public health systems in Latin America implement primary prevention strategies focused on individuals with prehypertension and HNBP.

Early identification of these pre-hypertensive states is crucial. As noted by Egan and Stevens-Fabry, prehypertension not only increases the risk of progression to hypertension but is also associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular events even before the development of frank hypertension.41 This underscores the need for broader and more effective screening programs in primary care, such as those proposed by Rubinstein et al. in their study on cost-effective interventions for non-communicable diseases in Latin America.42

The observed variability among countries in the prevalence of prehypertension and HNBP indicates that public health strategies must be adapted to specific national and local contexts. Thus, interventions should consider the cultural, socioeconomic, and health system particularities of each country. This could range from culturally adapted public education campaigns to nation-specific food regulation policies.

Moreover, it is essential to address the modifiable risk factors associated with prehypertension and HNBP. Lifestyle interventions, such as promoting healthy diet and increasing physical activity, have proven effective in preventing progression to hypertension. The ENCORE study by Blumenthal et al. demonstrated that these interventions can be particularly effective in individuals with prehypertension.43 Therefore, public policies that facilitate healthy lifestyle choices should be considered, such as improving public spaces for physical activity or regulating the advertising of unhealthy foods.

Finally, it is crucial to enhance public awareness about the significance of prehypertension and HNBP. Studies, such as that by Chow et al., found that hypertension awareness in Latin America was suboptimal,30 and awareness of pre-hypertensive states is likely even lower. Thus, public health campaigns should educate the population about the importance of regular blood pressure monitoring and adopting healthy lifestyles from an early age.

Strengths and limitationsOur study presents several strengths and limitations that warrant consideration. Among the strengths, the breadth of our systematic review stands out, encompassing multiple Latin American countries over an extended period, thus providing a comprehensive view of both pre-hypertensive states in the region. Furthermore, the inclusion of many participants increases the precision of our estimates. Additionally, the use of robust statistical methods, including random-effects models and meta-regression analyses, allowed us to address inter-study heterogeneity and explore potential factors influencing prevalence.

However, our study also has limitations. The significant heterogeneity observed among studies suggests that results should be interpreted with caution. This heterogeneity could be attributed to differences in blood pressure measurement methods, diagnostic criteria, and characteristics of the studied populations. Moreover, the uneven representation of Latin American countries, with some countries being overrepresented (such as Peru and Brazil) and others underrepresented or absent, limits the generalizability of our findings across the entire region. Additionally, the scarcity of studies on HNBP compared to prehypertension also restricts our conclusions regarding this condition.

Conclusions and recommendationsIn conclusion, our meta-analysis reveals a considerable prevalence of prehypertension (27.98%) and HNBP (19.23%) in the region, underscoring the magnitude of this public health problem. The significant variability observed among countries highlights the need for context-specific approaches tailored to each national setting. These findings have important implications for public health and clinical practice in Latin America.

In light of these findings, we recommend implementing broader and more effective screening programs in primary care for early detection of these pre-hypertensive states. Furthermore, it is crucial to develop and implement culturally appropriate lifestyle interventions focused on modifying risk factors such as diet, physical activity, and alcohol consumption. Moreover, it is necessary to enhance public awareness about the significance of prehypertension and HNBP through effective educational campaigns. Additionally, it is essential to expand research to Latin American countries currently underrepresented in the literature to obtain a more complete picture of the situation across the region, as well as conduct future research focused on better understanding the progression of these states to frank hypertension in our region. Indeed, attention to these pre-hypertensive states represents a crucial opportunity for primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases in Latin America.

Authors’ contributionVíctor Juan Vera-Ponce: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing-Original Draft, Writing-Review & Editing.

Joan A. Loayza-Castro: Methodology, Software, Data Curation, Formal analysis, Writing-Review & Editing.

Fiorella E. Zuzunaga-Montoya: Investigation, Project administration, Writing-Original Draft, Writing-Review & Editing.

Luisa Erika Milagros Vásquez-Romero: Investigation, Project administration, Writing-Original Draft, Writing-Review & Editing.

Nataly Mayely Sanchez-Tamay: Investigation, Methodology, Writing-Original Draft, Writing-Review & Editing.

Juan Carlos Bustamante-Rodríguez: Validation, Visualization, Supervision, Writing-Original Draft, Writing-Review & Editing.

Enrique Vigil-Ventura: Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing-Original Draft, Writing-Review & Editing.

Carmen Inés Gutierrez De Carrillo: Methodology, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing-Review & Editing.

Informed consentThis study is a systematic review, therefore informed consent is not required.

Financial disclosureThis study was financed by Vicerectorado de Investigación de la Universidad Nacional Toribio Rodríguez de Mendoza de Amazonas.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data availabilityData are available upon request to the corresponding author.

A special thanks to the members of Universidad Nacional Toribio Rodríguez de Mendoza de Amazonas (UNTRM), Amazonas, Peru for their support and contributions throughout the completion of this research.