Colonoscopy (CS) is an invasive diagnostic and therapeutic technique, allowing the study of the colon. It is a safe and well tolerated procedure. However, CS is associated with an increased risk of adverse events, insufficient preparation and incomplete examinations in the elderly or frail patient (PEA/F). The objective of this position paper was to develop a set of recommendations on risk assessment, indications and special care required for CS in the PEA/F. It was drafted by a group of experts appointed by the SCD, SCGiG and CAMFiC that agreed on eight statements and recommendations, between them to recommend against performing CS in patients with advanced frailty, to indicate CS only if the benefits clearly outweigh the risks in moderate frailty and to avoid repeating CS in patients with a previous normal procedure. We also recommended against performing screening CS in patients with moderate or advanced frailty.

La colonoscopia (CS) es una técnica invasiva, fundamental para el estudio del colon. Es un procedimiento seguro y bien tolerado. Sin embargo, en personas de edad avanzada o con fragilidad (PEA/F) aumenta el riesgo de acontecimientos adversos, preparación insuficiente o exploraciones incompletas. El objetivo de este documento de posicionamiento fue consensuar recomendaciones sobre valoración del riesgo, indicaciones y cuidados especiales necesarios para la CS en PEA/F. El documento fue redactado por un grupo de expertos designados por la SCD, la SCGiG y la CAMFiC entre 2020 y 2022. Se consensuaron 8 afirmaciones y recomendaciones, entre ellas: no realizar CS a los pacientes con fragilidad avanzada, indicar CS solo si los beneficios son claramente superiores a los riesgos en fragilidad moderada, no repetir CS en PEA/F que tienen una CS completa previa sin lesiones y no indicar CS de cribado en pacientes con fragilidad moderada o avanzada.

Colonoscopy (CS) is an invasive diagnostic and therapeutic technique, essential for the study of the colon and terminal ileum. It is a relatively safe and generally well-tolerated procedure. However, in elderly and/or frail people (E/F P), colonoscopy is associated with an increased risk of adverse events, insufficient preparation and incomplete examinations.1–7

The prevalence of diseases affecting the colon is higher in E/F P. Often, however, detection of the condition does not improve quality of life and does not affect survival.3 As an example, it takes a minimum of 10–15 years for colorectal polyps to progress to symptomatic colorectal cancer (CRC). This period of time is generally much longer than the life expectancy of an E/F P. In addition, post-polypectomy perforation or haemorrhage can have devastating consequences in E/F P. Therefore, the risk-benefit ratio of CS can be discernibly negative in E/F P.

Age in itself is not a contraindication for CS. In contrast, extreme frailty would fully contraindicate CS, as well as any other aggressive procedure. However, in moderate degrees of frailty, CS can facilitate diagnosis and direct treatment in order to improve the patient’s quality of life and/or functionality. In these cases, the risk-benefit ratio of the technique must be assessed on an individual basis.8

Finally, the indication for any invasive procedure – such as CS – should be based on shared decision-making by tailoring diagnostic and therapeutic options to the preferences of each individual.8–10

In summary, ethical obligations to do no harm and to respect the autonomy of the individual require careful and individualised assessment of the indication for invasive examinations such as CS.

The aim of this position paper is to set out recommendations on risk assessment, indications and special care needed for CS in E/F P.

MethodsThis consensus document was produced by a group of experts appointed by the SCD, the SCGiG and the CAMFiC between 2020 and 2022.

Each section was drafted by a multidisciplinary team that included a geriatrician, a family doctor and a gastroenterologist. The experts conducted a non-systematic review of the evidence and used the references retrieved and their bibliographic databases to write each section. Finally, the different sections were brought together in a single document. The controversial issues were discussed during several teleconferences over the course of 2021 and 2022. With the results of the discussions, the final document was drafted and was revised again by each of the experts. The final version of the document was approved at a final consensus meeting and subsequently approved by the boards of the respective societies.

ResultsTable 1 shows the main conclusions and recommendations of the working group.

Main conclusions and recommendations.

| The risk of serious CS complications in elderly and/or frail patients can vary from five serious complications per 100 CS to three serious complications per 1000 CS, depending on patient characteristics. The mortality rate is approximately one patient per 1000 CS |

| 2. Advanced frailty increases the risk of complications |

| 3. It is not recommended to perform CS in patients with advanced frailty (Frail-VIG > 0.5 or CFS ≥ 7). CS shall only be indicated in exceptional cases and after a specific and careful assessment of the case |

| In patients with moderate frailty, the risk-benefit ratio should be assessed individually and CS should be indicated only if the benefits clearly outweigh the risks |

| A prior negative CS or low-risk lesions markedly decrease the risk of relevant disease and especially neoplasia. Repeat testing, especially for suspected malignancy, is not recommended for frail or elderly people who have a recent (within the last 10 years) complete CS with adequate preparation without high-risk lesions |

| Screening CS, both population and follow-up polyp screening, is discouraged in patients with moderate or advanced frailty |

| Other than in exceptional cases, in patients without frailty, it is recommended to discontinue population-based CRC screening at no later than age 75 years |

| In patients without frailty and a history of colorectal polyps, other than in exceptional cases, it is recommended to discontinue screening at no later than age 80 years |

Limitations and complications in E/F P need to be taken into account when indicating a CS. In general, the literature does not refer to frailty, but only takes age-related complications into account. This probably leads to an underestimation of the real risk, as CS is preferentially indicated in individuals with a lower degree of frailty. Even so, it is well known that CS in elderly patients is associated with an approximately two-fold increased risk of perforation and other complications and an almost four-fold increased risk of hospitalisation. The absolute risk of complications remains generally low.1–7 However, at very old ages the absolute risk is also very high. In a retrospective observational study evaluating CS in very elderly patients, four out of 74 patients over 90 years of age had a major complication: myocardial infarction, symptomatic bradycardia and tachycardia, and severe post-polypectomy haemorrhage. No deaths occurred.4

Completed colonoscopy rates are also lower in elderly patients and range from 60% to 90% depending on the study. Meta-analyses show that approximately 80% (four out of five colonoscopies) can be completed up to the caecum. We do not have any reliable data on how many of these patients had inadequate preparation, preventing a detailed evaluation of the colonic mucosa. Studies suggest that rates of inadequate preparation in E/F P are between 10% and 40%.2–4

A reasonable estimate would be that one in five colonoscopies in E/F P cannot be completed up to the caecum and that between one and four in 10 will have suboptimal preparation.

Age is an unreliable predictor of the risk of complications.8 Despite evidence that frailty significantly increases the risk of complications in different clinical settings,11,12 there is virtually no data in the literature concerning CS. We have identified only one study that assessed the relationship between frailty and complications in CS.13 In this study, frailty was determined based on a test of muscle strength and coordination. Fifty out of 99 patients over the age of 50 were denoted frail or pre-frail. Three patients (6%, one in 15) in this group had major complications (one perforation, one haemorrhage and one acute myocardial infarction [AMI] during the test) compared to no major complications in the non-frail patients. The rate of complications was 74% (three out of four patients) in the pre-frail/frail group versus 40% (two out of five) in the non-frail group.

We should therefore consider that the majority of E/F P will have at least one (usually minor) complication of colonoscopy and one in 15 will have a severe complication. The expected benefits should therefore outweigh this level of risk of complications.

Complications can arise both in relation to the preparation (falls, fluid and electrolyte disorders, vomiting and aspiration) and in relation to the sedation (aspiration and respiratory arrest) or the CS itself (haemorrhage, perforation, cardiovascular and respiratory complications). The frequency and severity of these complications are clearly related to age and associated comorbidities.

We do not have an adequate estimate of complications secondary to preparation because, as they occur prior to the procedure, the patient often does not attend the endoscopy and they are not always recorded. The UK surveillance system reported 218 adverse events in 2009 over a five-year period. Most were mild, but there were 13 moderate or severe events, including one death.14 In response to these data, the British Society of Gastroenterology published recommendations on the prescription and administration of oral bowel preparation.15

Data on the complications of sedation and colonoscopy are shown in Table 2.2

Risk of complications per 1000 endoscopies based on the meta-analysis by Day et al.2

| Age (years) | >65 | >80 |

| Total adverse effects (% [95% CI]) | 26 (25–27) | 35 (32–38) |

| Perforation (% [95% CI]) | 1 (0.9–1.5) | 1.5 (1.1–1.9) |

| Bleeding (% [95% CI]) | 6.3 (5.7–7.0) | 2.4 (1.1–4.6) |

| Cardiovascular complications (% [95 CI]) | 19.1 (18–20) | 28.9 (26–32) |

| Serious cardiovascular complications (% [95% CI]) | 12.1 (11–13) | 0.5 (0.06–1.9) |

| Mortality (% [95% CI]) | 1.0 (0.7–2.2) | 0.5 (0.06–1.9) |

Therefore, we can estimate that three out of 100 to three out of 1000 E/F P will have a serious complication of colonoscopy, depending on the degree of frailty. The range published in the literature is extremely wide due to the marked heterogeneity with respect to age, comorbidity and, above all, degree of frailty. The expected mortality rate of the test is one in 1000 patients.

Indications for colonoscopy according to degree of frailtyAccording to our working group’s previous position paper,8 it is recommended that the Clinical Frailty Score (CFS) and the Frail-VIG frailty index (FI) be used to assess the degree of frailty. Both have been shown to be highly reliable predictors of prognosis and are available as online calculators.12,16–21

Indications in advanced Frailty (Frail-VIG FI > 0.5 or Clinical Frailty Score ≥ 7)In E/F P with advanced frailty with Frail-VIG FI > 0.5 or CFS ≥ 7, diagnostic-therapeutic goals are usually aimed at ensuring well-being and symptomatic control. They are usually not amenable to invasive measures —including CS— due to shorter life expectancy, a higher prevalence of comorbidities and geriatric syndromes and a very high risk of complications.8,16

Endoscopic exploration could only be considered in exceptional cases where geriatric or palliative care assessment considers that there may be symptomatic benefit (such as decompression of a volvulus, colostomy or placement of a stent).

Indications in mild-moderate frailty (Frail-VIG FI 0.2–0.5 or CFS 5–6)In E/F P with mild–moderate frailty, diagnostic and therapeutic goals focus on promoting and maintaining autonomy. Therefore, CS would be indicated only if the outcome can improve the patient’s functionality and/or quality of life.8,16

No frailty or pre-frailty (Frail-VIG FI < 0.2 or CFS 1–4)In E/F P with no frailty or pre-frailty —Frail-VIG FI < 0.2 or CFS 1–4— the diagnostic-therapeutic goals are similar to those of the general population, and preventive measures to improve survival should also be considered.8,16

Who should have a colonoscopy depending on the indication?As discussed above, in moderately frail E/F P, preservation of function will prevail over survival. In more advanced cases, the therapeutic goal will be the patient’s well-being. For this reason, the appropriateness of the indication for CS has to be based on both the patient’s clinical signs and symptoms and degree of frailty.

Diverticulosis, haemorrhoids, constipation or incontinence become more common with age. CRC is also much more common in symptomatic elderly patients. However, a non-invasive diagnosis (e.g. by CT scan for diverticula) may be sufficient to guide further treatment in E/F P. On the other hand, a diagnosis of CRC may be of no benefit—or even have negative consequences—if the patient is not amenable to active treatment.

The results of previous colonoscopies should always be considered. As an example, a previous CS can provide guidance on the origin of rectorrhagia. It will also often allow us to rule out large lesions such as advanced neoplasia, even if CS preparation has not been optimal.

In addition, a previous normal CS or non-advanced polyps in the previous 10 years reduces the risk of CRC to less than five per 1000 patients.22–24 Given the aforementioned risks and the low likelihood of significant disease, the general recommendation is not to repeat colonoscopy in E/F P with a complete CS and recent adequate preparation, understood as endoscopy performed within the last 10 years. Therefore, CS should be repeated only in exceptional cases and always assessing the specific situation and the individual risk-benefit ratio.

Careful consideration should also be given to the reasons why a previous CS could not be conducted or was incomplete or ill-prepared, in order to take measures to avoid a repeating the same mistake. A previous CS that is incomplete or ill-prepared for reasons that cannot be resolved or prevented will contraindicate the CS and make it necessary to consider alternative examinations.

RectorrhagiaThe incidence of CRC identified in CS is higher in elderly patients than in the general population. In this sense, the presence of rectorrhagia is the main risk factor for neoplasia among the elderly. This risk may be even higher in E/F P aged >90 years compared to younger E/F P.4 However, the most common cause of rectorrhagia in these patients is still benign disease.

In mild rectorrhagia it is recommended to initially assess for symptoms or signs of high risk for CRC and previous episodes and known causes of rectorrhagia (haemorrhoids, diverticula, risk factors and previous episodes of ischaemic colitis, prostate or endometrial radiotherapy) or previous endoscopic studies. If CRC is not highly suspected —or if it would not be treatable— or if there is already a known cause of rectorrhagia, in moderate to severe frailty, CS is not routinely recommended in the initial episode.

As such, in mild episodes, screening would only be indicated for patients in good functional states who are amenable to measures to increase survival and who do not have a recent complete CS.

However, in severe or recurrent bleeding with significant clinical impact, CS may be indicated to assess the aetiology and attempt endoscopic treatment, even in E/F P with moderate frailty.

Finally, in patients with very advanced frailty, CS would not be indicated and symptomatic treatment and comfort measures should be considered as an initial strategy.

In any of these scenarios, a previous CS without lesions markedly decreases the diagnostic yield of the test and reinforces the recommendation not to perform a CS. In addition, it is recommended to always consider the option of using less invasive examinations such as abdominal CT prior to the indication for CS.

In moderate/severe haemorrhage that requires emergency department evaluation, previous studies and known causes of bleeding must be evaluated. If there is haemodynamic instability and there is no therapeutic limitation to palliative treatment, initial study by CT angiography is recommended. Early haemodynamic stabilisation is essential to prevent the onset of accelerated deterioration of the E/F P. In the event of stability, CS will be indicated to diagnose the cause (such as angiodysplasias, diverticula or ulcers) and, if possible, treat bleeding or potential causes of recurrence according to the previous assessment of the degree of frailty.

Alternative examinations: an abdominal CT scan prior to CS should be considered, especially in case of suspected diverticular bleeding or ischaemic colitis.

AnaemiaAnaemia is a common finding in old age and the causes can be highly varied. Before colonoscopy is indicated, a complete blood test including iron metabolism should be performed to confirm that the disease is iron deficiency anaemia and not anaemia of chronic disease.

In case of iron deficiency anaemia, CS is indicated if the information it provides could be useful for the management of the patient, e.g. by local treatment of angiodysplasia or for the prognostic information it could provide. Although in a British study the most frequent warning symptom in patients >85 years with CRC was anaemia (53%),25 the most frequent cause of iron deficiency anaemia in frail patients is not CRC, but intestinal angiodysplasia and the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Geriatric assessment is essential, because if the patient is not a candidate for active treatment due to his or her underlying disease, the risk-benefit ratio of CS would be unfavourable and it would not be indicated.

It must be ruled out that it is not a long-standing and stable anaemia or that there is no previously known cause. If the patient has a recent (under 10 years ago) previous negative CS without neoplasia, repeat endoscopy is not recommended.

In patients with long-standing cardiovascular disease and on antiplatelet and/or anticoagulant therapy, iron deficiency secondary to chronic occult bleeding due to intestinal angiodysplasia is very common, which may also justify a positive faecal occult blood (FOB) test. CS can detect bleeding angiodysplasia and therefore facilitate endoscopic treatment. However, angiodysplasias respond poorly to endoscopic treatment. The probability of recurrence after the first bleeding episode is 50%, mainly because the large number and diffuse location of the lesions makes detection and treatment difficult.

Performing an immunological FOB test may decrease the number of CS without findings. Its negative predictive value —and therefore its ability to predict that there will be no significant lesions in CS— is very high. Therefore, if the patient is considered to be a candidate for study, it is recommended to perform a FOB test prior to the indication for CS and to consider other examinations such as gastroscopy beforehand if the FOB is negative.

Alternative tests: there are currently no alternative tests to CS for the study of FOB-positive iron deficiency anaemia. In the future, it is possible that colon capsule endoscopy may play a role in this indication.

DiarrhoeaCS is not recommended for acute diarrhoea. Chronic diarrhoea is defined as decreased stool consistency, stools that cause urgency or abdominal discomfort, or an increase in stool frequency, every day and lasting more than four to six weeks. In these cases, CS assessment may be indicated once the most common causes (drugs, especially metformin, parasites, malabsorption, etc.) have been ruled out, or if signs of organicity or severity are present (Table 3).

Organic diarrhoea/warning signs criteria.

| Blood in the faeces |

| Fever |

| Recent weight loss > 5 kg (without depressive syndrome) |

| Recent onset of symptoms (or change in symptom characteristics) |

| Family history of CRC or colorectal polyps |

| Nocturnal diarrhoea |

| Diarrhoea persisting during fasting |

| Steatorrheic or very abundant stools |

| Abnormal physical examination, abdominal masses, rectal mass, etc. |

| Anaemia, hypoalbuminaemia, elevation of acute phase reactants |

| Positive faecal occult blood test |

Severe diarrhoea with incontinence can be very limiting. Even in E/F P with relatively advanced frailty, the diagnosis of a treatable disease, such as microscopic colitis, and its appropriate treatment could improve quality of life. Therefore, in these cases the threshold for indicating a CS may be low if all other examinations have been negative. Again, it is important to assess whether recent CS and/or colon biopsies are available and to bear in mind that in advanced frailty, empirical symptomatic treatment is preferable.

ConstipationConstipation is very common in E/F P, caused by many factors, including drugs, decreased mobility and dehydration. In general, CS should not be indicated unless it is associated with clear warning signs (Table 2), always assessing the risk-benefit ratio and whether a previous CS has been performed. Worsening constipation due to justified causes (immobilisation, drugs, etc.) should not be considered a warning symptom.

In patients with reduced mobility, faecalomas may manifest as constipation or subocclusive conditions. Intensive laxative treatment with clinical follow-up is recommended before considering CS in these cases.

Alternative tests: digital rectal examination should always be carried out beforehand. There are no alternative examinations for the study of constipation, although an abdominal CT scan may diagnose CRC and rule out other complications such as faecalomas.

Abdominal painIsolated abdominal pain, without other symptoms, should not be an indication for CS as an initial test. Symptoms, signs of organicity and physical examination should be carefully assessed to establish a guided diagnostic suspicion (Table 2) and blood work-up and non-invasive examinations should be prioritised. A positive FOB test may indicate disease of the colon. On the other hand, a negative result has a very high negative predictive value for ruling out significant lesions in the colon. If previous colonoscopies are available without significant abnormalities, it is strongly recommended not to repeat the examination.

Alternative tests: an abdominal ultrasound or an abdominal CT scan may be considered. If disease of the colon is suspected after these examinations, CS may be indicated depending on the risk-benefit ratio.

IncontinenceIncontinence is more common in E/F P due to weakness of the anorectal musculature. Neurological disorders or cognitive impairment and pelvic floor dysfunction also foster incontinence. CS is not recommended for incontinence study if there are no other associated symptoms or signs of risk (Table 2). In incontinence, a digital rectal examination should always be performed first. It should also be borne in mind that the therapeutic options for E/F P are limited and generally poorly tolerated.26 If there is no previous CS and if, after evaluation by the coloproctologist, it is considered necessary, CS can be indicated, provided that frailty is assessed in advance.

ScreeningPopulation screening: screening for any condition should be stopped when the benefits do not clearly outweigh the risks. CRC screening in the general population aged 50-75 years is associated with a decrease in CRC mortality of approximately 1 in 100 patients at 10, 20 and 30 years, with no reduction in overall mortality observed.27 In addition, the benefit of screening on survival is evident after at least five years. Moreover, the time to develop CRC from “normal” mucosa is between seven and 12 years and survival for untreated CRC is around three years.

Given the limited efficacy of screening, the increased risk of CS complications and the fact that it takes up to 10 years for the effects on survival to become apparent, most publications consider that the risk of screening outweighs the benefit from the age of 75 years in individuals without comorbidity.28 Above this age it is debated whether screening can be considered on an individual basis. As such, the American guidelines establish an area of uncertainty between 76 and 85 years of age. Some guidelines even recommend CS between 76 and 85 years of age, especially if it has not been done before, always in individuals without comorbidity.29

In conclusion, it is recommended to discontinue CRC screening at 75 years of age in the general population. In younger individuals, screening should be stopped if life expectancy is less than 10 years and if there is significant comorbidity or moderate to severe frailty, with a CFS of four or more and a Frail-VIG FI of approximately 0.3.

Screening in patients with polyps: when to stop, differences according to grade?The literature is very sparse, but non-advanced adenomas (less than 1 cm) are considered to have no prognostic implication. Therefore, screening should be discontinued if the adenomas on previous CS were non-advanced and the patient is 80 years of age or older. Further screening would also not be indicated in patients with a life expectancy of less than 10 years.30 On the other hand, some experts recommend colonoscopies every one to three years as long as advanced lesions are detected until life expectancy is less than five years. This would be at approximately 90 years of age in patients without comorbidity and is equivalent to a CFS of 5 or Frail-VIG FI of 0.35.29

Which polyps should and should not be resectedIn general, in patients over the age of 80–85 years without comorbidity, the risks of resection of non-advanced polyps probably outweigh the benefits. This age may be even lower in patients with CFS above 4 or a Frail-VIG FI above 0.35.

An elderly or frail patient in whom an advanced, large lesion and/or high-grade dysplasia or carcinoma in situ is detected constitutes a special situation. In these patients the surgical risk is high. Postoperative mortality in patients operated on for CRC is 3.7% at 70–79 years, 9.8% at 80–89 years and over 12.9% at 90 years.30 It is difficult to recommend surgery with a mortality of 10%–13% in patients with an average life expectancy of six years. However, the likelihood of a tumour with the described characteristics affecting general condition and/or quality of life is high. Therefore, it is reasonable to offer an attempt at endoscopic treatment to patients in their 90 s without comorbidity and to all patients whose life expectancy exceeds five years.31,32

Utility of faecal occult blood testing in elderly and/or frail peopleIf CRC screening has been discontinued, it is not recommended to do sporadic FOB testing for opportunistic screening. The FOB test has a very high false positive rate and a very low specificity in E/F P, such that if it is negative it reasonably rules out disease but, conversely, a positive test does not necessarily imply clinically relevant disease. The number of false positives is especially high in patients on antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy and/or those with advanced respiratory, cardiovascular or renal disease. Kistler et al.33 evaluated a series of 212 people over 70 years of age who had a positive FOB test in the context of abdominal symptoms. Grouping patients according to life expectancy, they found that the benefit-complication balance was unfavourable in 87% of patients with the worst life expectancy and 65% of patients with the best prognosis. Consequently, evidence on the use of FOB in E/F P with symptoms is limited. The data suggest that only patients without underlying disease —and only to a limited extent— benefited from FOB testing.

In any case, if already determined, a negative FOB test has a very high negative predictive value for ruling out advanced polyps and neoplasia. A negative FOB test is therefore an important argument against subjecting E/F P to the risk of CS.

Therefore, a faecal occult blood test alone or as screening for non-specific symptoms is not recommended in E/F P, especially in those with cardiovascular disease and receiving antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy. It is also not recommended that a CS based on FOB be performed in those patients with a previous colonoscopy indicated by positive FOB test without significant findings.

Again, the indication for CS has to be assessed taking into account the risk-benefit ratio of both screening and potential treatments in the event advanced neoplasia is detected.

Technical considerationsRecommendations for colonoscopy preparationThe quality of preparation is a critical factor in the performance and safety of CS. There are limited data on the safety and efficacy of CS preparation in E/F P. Age over 65 years has not consistently been shown to be a risk factor for poor preparation. However, most of the risk factors for poor preparation are associated with comorbidity.34,35 Moreover, functional impairment, advanced heart and renal failure and chronic electrolyte disorders are a challenge when it comes to achieving correct preparation safely.

Choosing the evacuating solutionIn choosing the evacuating solution, the patient’s ability to take the preparation and their comorbidity must be considered. It is not possible to offer a single guideline that covers all scenarios. Osmotically neutral solutions, generally of high volume, are preferred for their safety profile in this type of patient. However, they require the ingestion of up to four litres of liquid and therefore are poorly tolerated. In contrast, hyperosmolar solutions are generally better tolerated, but have a poorer safety profile. There are different evacuating solutions containing different active ingredients. The main ones available in Spain are: polyethylene glycol (PEG) (Bohm's Solution®, MoviPrep® and Pleinvue®), sodium phosphate (Fosfosoda®) and sodium picosulfate combined with citric acid and magnesium oxide (Citrafleet® and Picoprep®). Due to its safety profile, Fosfosoda® is not recommended for use in E/F P.34,36,37

It should be noted that Citrafleet® is a hyperosmolar solution and is contraindicated in patients with congestive heart failure, severe renal failure, hypermagnesaemia, a history of rhabdomyolysis and gastrointestinal ulcers. It should be used with caution in patients on a low sodium diet or who are taking medications that may alter electrolyte balance. Low quality data are available associating hyperosmolar preparations with an increased risk of admission for hyponatraemia in patients over 65 years of age.37

PEG is the substance with the best safety profile.15,34,36,38–40 It should be noted that there are different formulations, balanced or otherwise, with or without sulphate and of varying volume. The safest and most tested formulation is known as Bohm’s solution. It has the characteristic that it is practically not absorbed and maintains a neutral ionic balance.41,42 However, some cases of fluid overload have been reported in patients with severe ventricular dysfunction, renal impairment and treatment with potassium-sparing drugs.41–43 Particular caution should be exercised in patients with heart failure and severe NYHA functional class iii or iv or severe renal impairment with glomerular filtration rate <30 ml/min. In high-risk or decompensated patients, if CS cannot be postponed, in-patient preparation is recommended to ensure proper support and monitoring.

In cases of good functional status and no comorbidity, a reduced-volume solution containing PEG (Moviprep® or Pleinvue®) or containing sodium picosulfate and magnesium citrate (Citrafleet® or Picoprep®) can be considered. While it may be feasible to use some of these low-volume products in E/F P, the available safety data in these patients are limited and their use is therefore not currently recommended.

General measures to be taken into account for successful preparationIt is essential that the patient or, where appropriate, the caregiver understands the preparation guidelines. To this end, it is useful to schedule a specific consultation agenda dedicated to explaining the preparation and answering questions, either in the hospital or in primary care.44

In general, it is recommended to split the preparation into two parts, both for morning and afternoon preparations. For morning colonoscopies, preparation can be split between the day before the colonoscopy and the day of the colonoscopy. For afternoon colonoscopies, preparation can be done in the same way or alternatively in two parts, on the morning of the colonoscopy. Split preparation improves tolerance, adherence to the evacuating solution and ultimately the quality of the examination.45,46 A meta-analysis has demonstrated the impact of completing preparation two to five hours before the colonoscopy, which has been termed the “golden five hours”.46 It is important to convey the importance of following the established times so that the examination can be performed, reducing the risk of aspiration and achieving quality preparation.38

It should be noted that the second part of the preparation must often be taken in the early hours of the morning, and this may be associated with an increased risk of confusional states or falls. Therefore, precautions must be taken and the caregiver must pay special attention and accompany the patient in the process. If the patient is at risk and resources are not available, a scheduled admission for preparation may be considered.

In case of risk of poor preparation, defined as previous poor preparation, constipated habit or a high score on risk scales,35 adjuvants can be added in addition to reinforcing the above measures. There is no quality evidence available to give a concrete recommendation,47 but a common and reasonable practice is to add low doses of bisacodyl 5 mg every 12 h for three days prior to colonoscopy.

Anti-coagulant or antiplatelet therapy pre-colonoscopy managementThe recommendations are based on the European guidelines on anticoagulation and endoscopy.48CS should always be considered a high-risk examination for bleeding, because there is always the possibility of finding lesions that require treatment. The patient should be prepared in case treatment is necessary and repeat colonoscopies should be avoided whenever possible.

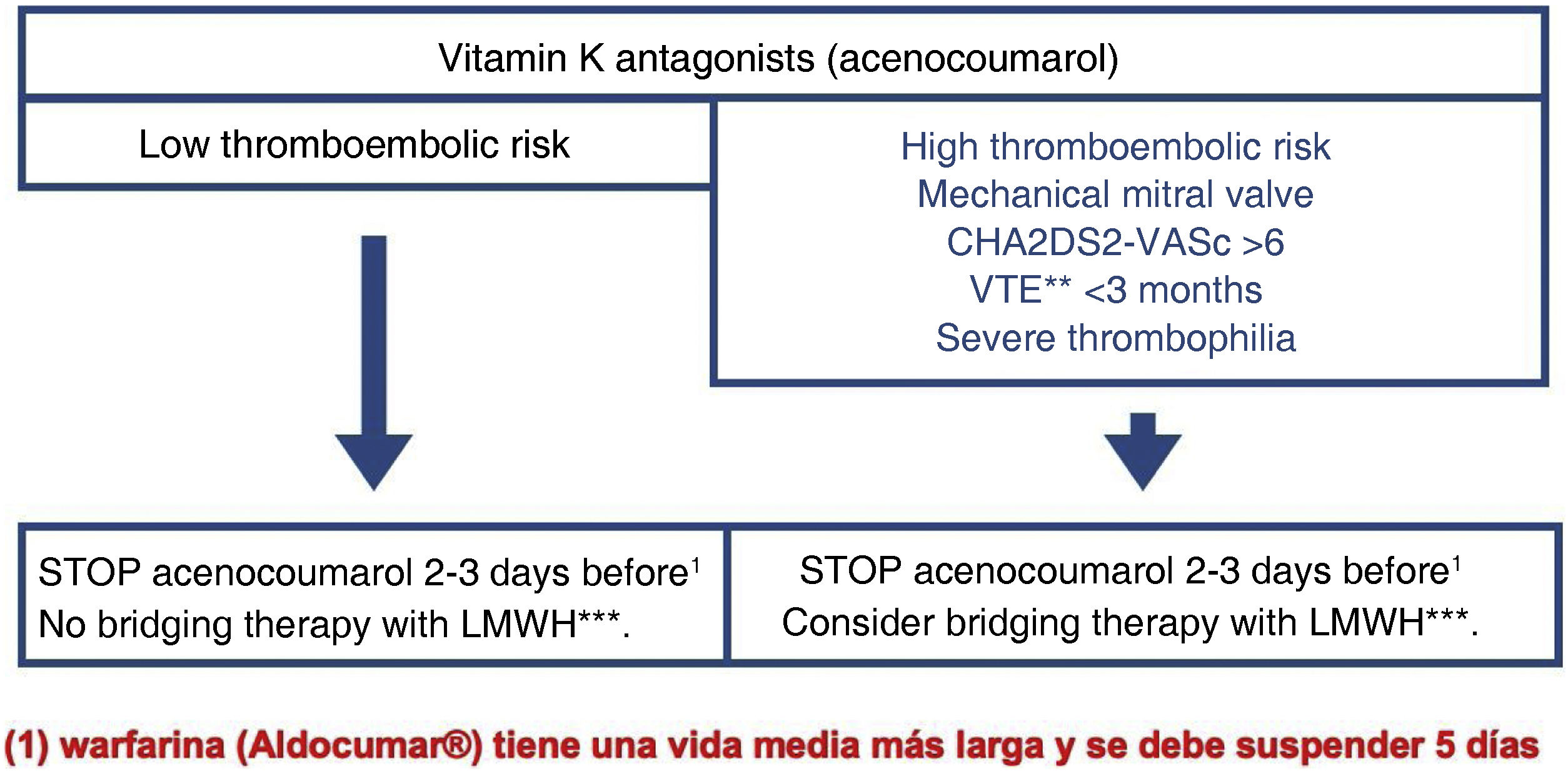

Antiplatelet therapy: the patient must be classified according to his/her thrombotic risk into high and low risk (Fig. 1).

For patients with simple antiplatelet therapy, maintaining acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) at low doses (100 mg/day) is recommended. If the patient comes to the procedure with higher doses, e.g. 300 mg, postponing the colonoscopy is neither necessary nor justified. In cases where monotherapy is with a P2Y1 inhibitor, discontinuation of the drug is recommended. The recommended timings are: ticagrelor five days beforehand, clopidogrel five days, prasugrel seven days. They should be substituted with ASA 100 mg whenever possible. If the patient is being treated with NSAIDs, the procedure can be performed, regardless of the dose and type of NSAID.

For patients requiring dual antiplatelet therapy, the need for colonoscopy should be assessed while the thrombotic risk is high. If colonoscopy can be delayed, it should be postponed until the patient’s thrombotic risk is considered low. It is generally recommended to discontinue the P2Y inhibitor and maintain ASA whenever possible.

Anticoagulant therapy: anticoagulant therapy must be discontinued for the CS to be performed. It is generally recommended to discontinue acenocoumarol two to three days beforehand and warfarin five days beforehand (Figs. 2 and 3).

Management of anticoagulation with acenocoumarol in E/F P requiring CS. CS should always be considered a high bleeding risk examination because of the possibility of finding lesions susceptible to treatment, thereby avoiding further examinations.

LMWH, low molecular weight heparin; TE, thromboembolic; VTE, venous thromboembolic.

This recommendation only applies to patients with stable INR. For patients with labile INR, it may be necessary to assess INR before the examination.

For DOACs, since their pharmacokinetics are predictable and dependent on renal function, the time at which to discontinue them is based on creatinine clearance (Fig. 3).

Bridging therapy with low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) is not indicated as it increases the risk of bleeding without decreasing the risk of a thromboembolic event. Only in cases of very high thromboembolic risk can it be indicated in bridging therapy with LMWH and only in patients on antivitamin K therapy.

Restarting anticoagulant therapy: there are few studies that provide data on the optimal time to restart antithrombotic therapy48 if it is discontinued after elective endoscopic therapy. The individual risk of bleeding versus the risk of thrombosis must always be taken into account. Remember that the onset of action of DOACs is within a few hours, while the onset of action of antivitamin K is >12–24 h. The PAUSE study therefore recommends starting DOACs 24–48 h after the procedure (Fig. 3). A recent prospective cohort study49 found that starting DOACs immediately after polypectomy, rather than a delay of 24–48 h (as suggested by guidelines), doubled the risk of late bleeding without a reduction in thrombosis, although it did not reach statistical significance (14.3% vs 6.6%, p = 0.27). For procedures with a very high risk of bleeding, such as endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), an even later restart is recommended.50 The risk of bleeding following ESD was not significantly increased if antithrombotic therapy was started seven days after ESD, whereas starting immediately ≤1 week after ESD was significantly associated with increased delayed bleeding. Finally, it should be remembered that bridging therapy with LMWH is not indicated, as it increases the risk of bleeding without reducing the risk of thrombosis.

Conflicts of interestXavier Calvet reports no conflicts of interest related to this document. Other conflicts of interest: grants or contracts from AbbVie, Janssen, Kern, Takeda. Payment or fees for conferences, presentations, speakers’ bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from AbbVie, Janssen, Takeda, Galapagos and Kern. Support to attend meetings and/or travel for Ferring, Janssen, Abbvie and Sandoz.

Salvador Machlab reports no conflicts of interest related to this document. Other conflicts of interest: payment or fees for conferences, presentations, speakers’ bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events from Norgine. Support to attend courses, congresses or meetings: Ferring, Norgine, Casen Recordati and Boston Scientific.

The other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.