Non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS) is the latest pathology incorporated into the group of gluten-related disorders. This review addresses the evidence on its etiology, differential diagnosis and symptomatology. Although NCGS is defined by a reaction to gluten, other possible etiopathogenic mechanisms have been described, such as an inadequate response to other components of wheat or to FODMAPs, with the term non-celiac sensitivity to wheat recently being extended. There are contradictory results on the validity of the diagnostic protocol of the Salerno experts. Evidence on diagnostic biomarkers for NCGS is scarce, although some studies indicate the following: antigliadin antibodies, zonulin, ALCAT test, micro-RNA, incRNA and certain cytokines. In NCGS, abdominal pain and fatigue are the most common symptoms. In addition, altered nutritional status is common. In conclusion, more research on NCGS is needed to improve understanding of its etiopathogenesis and clinical features.

La sensibilidad al gluten no celiaca (SGNC) es la última patología incorporada al grupo de trastornos relacionados con el gluten. Esta revisión aborda la evidencia sobre su etiología, diagnóstico diferencial y sintomatología. Aunque la SGNC se define por una reacción al gluten, se han descrito otros posibles mecanismos etiopatogénicos, como una respuesta inadecuada a otros componentes del trigo o a los FODMAP, extendiéndose últimamente el término sensibilidad al trigo no celiaca. Existen resultados contradictorios sobre la validez del protocolo diagnóstico de los expertos de Salerno. La evidencia sobre biomarcadores diagnóstico para la SGNC escasea, aunque algunos estudios señalan los siguientes: anticuerpos antigliadina, zonulina, prueba ALCAT, micro-ARN, incARN y ciertas citoquinas. En la SGNC, el dolor abdominal y la fatiga son los síntomas más comunes. Además, es frecuente la alteración del estado nutricional. En conclusión, se necesita más investigación sobre la SGNC, para mejorar nuestro conocimiento de su etiopatogenia y clínica.

Gluten-related disorders (GRD) are a growing and significant health problem. These disorders can be classified into three groups: 1) allergic responses; 2) autoimmune diseases, such as dermatitis herpetiformis, gluten ataxia and coeliac disease (CD); and 3) non-coeliac gluten sensitivity (NCGS), the most recently reported GRD.

NCGS is characterised by a reaction to gluten, both intestinal and extraintestinal, in patients who improve clinically on a gluten-free diet (GFD).1–3 The prevalence of this disorder is not well defined, but one study determined that up to 13% of the population had a self-diagnosed sensitivity to gluten, and that it is more common in women.4 Although the concept of NCGS was first coined more than 40 years ago,5 there is still no clear consensus on the aetiopathogenesis, diagnosis or treatment of this disorder. The variety of symptoms, their impact on quality of life and the estimated high prevalence all point to the need for study. Although there is one relatively recent review on this disorder,6 it is not exhaustive in: 1) the description of the symptoms, not including an analysis of their prevalence; 2) the differential diagnosis with other related diseases; and 3) the review of biomarkers with diagnostic utility. Our aim with this paper was therefore to critically summarise the currently available clinical information on NCGS.

Literature search methodologyThe search was carried out in three different databases: MEDLINE (through the PubMed search engine), Scopus and Web of Science, and the same search criteria were followed throughout. In the Scopus and Web of Science databases, the default search is carried out in title, abstract and keywords; while in PubMed it is done in all fields. Therefore, to unite criteria, in PubMed we selected the option to perform the search in title and abstract fields. The search was performed using the following algorithm: “non-celiac gluten sensitivity” OR “non-celiac wheat sensitivity”. The search was carried out on 22 February 2021.

Studies published in Spanish and English were included, but articles based on unusual cases or focused exclusively on other gluten-related diseases were excluded.

Results and discussionAetiology of non-coeliac gluten sensitivityAlthough by definition NCGS consists of an abnormal reaction to gluten ingestion in non-CD patients, some studies have shown that a certain number of patients diagnosed with NCGS can tolerate gluten. Moleski et al looked at the effects of low (0.2g/day) and high (2g/day) gluten intake in patients with NCGS, and found no significant worsening of the patients compared to the healthy control group. However, the results of this study are strongly limited by the gluten doses in both intervention groups, which were very low compared to the recommendations of the Salerno experts (8g/day).7

With a similar aim, Roncoroni et al analysed the symptomatic response of 24 patients with NCGS to increasing doses of gluten: first week: 3.4–4g/day; second week: 6.7–8g/day; and third week: 10–13g/day. A subgroup responded immediately and adversely to low doses, reporting a deterioration in their general well-being and quality of life. However, other patients were able to cope with higher doses with no adverse effects.8 In fact, current evidence leads us to think that patients with NCGS can follow a less strict diet, in which some of them may consider a certain gluten intake without developing symptoms.9 These results would seem to demonstrate the aetiological theory of NCGS, and open the door to other possible causes of this disorder.

Role of FODMAPsFODMAPs (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols) are indigestible carbohydrates10 found in a wide variety of commonly eaten foods such as fruits, vegetables, legumes, cereals, dairy products and derivatives, sweeteners and honey.10,11 The evidence reported by some studies suggests that FODMAPs, rather than, or in addition to, gluten may be the stimulus that develops the abnormal response in individuals with NCGS. The gastrointestinal symptoms of some patients with NCGS seem to improve when following a diet low in FODMAPs.12,13 At the same time, sensitivity to FODMAPs could explain the worsening of symptoms reported after eating gluten-free flour in almost half of the subjects with NCGS in the double-blind cross-over trial by Zanini et al.14 Furthermore, in a study comparing the effect of gluten intake with that of fructans (a type of FODMAP) in patients with self-diagnosed NCGS, it was found that the severity of the symptoms reported after the intake of fructans (Gastrointestinal Symptoms Rating Scale [GSRS] score=38.6±12.3) was higher than after gluten intake (33±13.1), the difference being statistically significant.15 In fact, a GFD involves a partial reduction of FODMAPs,16 as some foods containing them, such as wheat or rye, are excluded,11 which could explain the improvement in symptoms in patients with NCGS when following a GFD without gluten necessarily being the origin of the disorder.

Alternatively, a recent study has suggested that NCGS has a multifactorial aetiology, involving an immune response to gluten, an alteration in the microbiota and an effect triggered by FODMAPs.16 Dieterich et al concluded that when NCGS patients reduce their intake of FODMAPs, the severity of the gastrointestinal symptoms reduces significantly, resulting in a general improvement and better psychological well-being, which further increases if gluten is also excluded from the diet.16 Lastly, another possible hypothesis put forward for the aetiology of NCGS by Biesiekierski et al is that gluten induces symptoms only in the presence of FODMAPs.12

Diagnosis of non-coeliac gluten sensitivityThere are no specific clinical manifestations or biomarkers defined at present for the diagnosis of NCGS.17–19 Consequently, diagnosis is based on exclusion criteria and on the assessment of symptomatic responses,17 so there is a need to seek alternatives that provide a clear, objective and definitive diagnosis.19,20 In spite of everything, the most accepted criteria today for the diagnosis of NCGS are those set out in the Salerno experts’ protocol.19 Although this protocol cannot be used in clinical practice due to its enormous complexity, it is nonetheless valuable given the high heterogeneity of NCGS, as it allows the homogeneous selection of patients for clinical trials or observational studies.

Salerno experts’ protocolThe first step consists of putting a patient who has been on a gluten-containing diet (GCD) for at least six weeks on a GFD for another six weeks. The clinical response to this new diet is assessed weekly through questionnaires where the patient records the Gastrointestinal Symptoms Rating Scale (GSRS) score (with a modified scale) for one or up to three main symptoms, comparing the baseline symptoms, prior to the GFD, to those that appear during the GFD. A patient is considered a responder when there is a reduction of at least 30% in the severity of one to three main symptoms compared to the baseline value or in at least one symptom without a worsening in the other symptoms, for at least three of the six weeks of follow-up.19

Next, to confirm the diagnosis of NCGS in patients who respond to the GFD, a double-blind placebo-controlled trial (DBPCT) with gluten intake is conducted. The trial consists of ingesting 8g of gluten per day for one week while following a GFD, followed by a washout week maintaining the GFD, and then crossover with placebo combined with the GFD. Instead of being weekly as in the first step, the assessment of symptoms is daily in this trial. As in step one, to identify the patient as NCGS (responder), there should be a difference in symptom severity of at least 30% between the week in which gluten is administered and the week in which placebo is administered.19

Limitations of the Salerno protocolAlthough this seems to be the best diagnostic option to date for NCGS in a research context, it is not without its limitations,19 as the results of some studies have led to questions about its reliability.14,20,21 Elli et al showed that the majority of patients (75.5%) who suffered from recurrent gastrointestinal symptoms, ate a GCD and had previously had CD and wheat allergy ruled out, responded well to a GFD; while only a minority (14% of the cohort) responded to the DBPCT trial and were finally diagnosed with NCGS.20 These results are in line with those of Di Stefano et al.21 and Zanini et al published in 201514 where, in patients who met the Salerno criteria for the diagnosis of NCGS and were considered GFD responders, only 34%14 and 52%,21 respectively, of the participants were finally diagnosed with NCGS after the blind gluten challenge test. The sample sizes in these last two studies may have been small, but they are supported by the findings of the Kabbani et al study of 238 patients with gastrointestinal symptoms who responded to a GFD; when challenged with the gluten test, only 52.5% were diagnosed with NCGS.9 One possible explanation for the individuals who respond to a GFD without really having NCGS (as they do not respond to gluten intake) is that the actual medical follow-up established for participating in the study was responsible for the clinical improvement in patients with a non-gluten-related functional gastrointestinal disorder.

Another limitation observed in the diagnosis of NCGS following the Salerno protocol is the "nocebo" effect, according to which patients could anticipate the possible consequences of the blind gluten test and show symptoms in response to placebo.11,12,15,20,21 In a similar vein, in the study carried out by Zanini et al in 2015,14 with NCGS subjects who were on a GFD because they thought they responded to it, 16% of the sample did not react to any of the blind, placebo or gluten intakes, suggesting that the day-to-day symptoms when ingesting gluten may be the result of psychological anticipation.14

These results, together with the growing evidence of a possible role of FODMAPs in the aetiology of the disorder (as previously mentioned), have weakened the use of the term NCGS1,12,14,16 and meant that more and more researchers tend to call this disorder non-coeliac wheat sensitivity17,20,22,23.

Clinical and diagnostic differentiation with other diseases

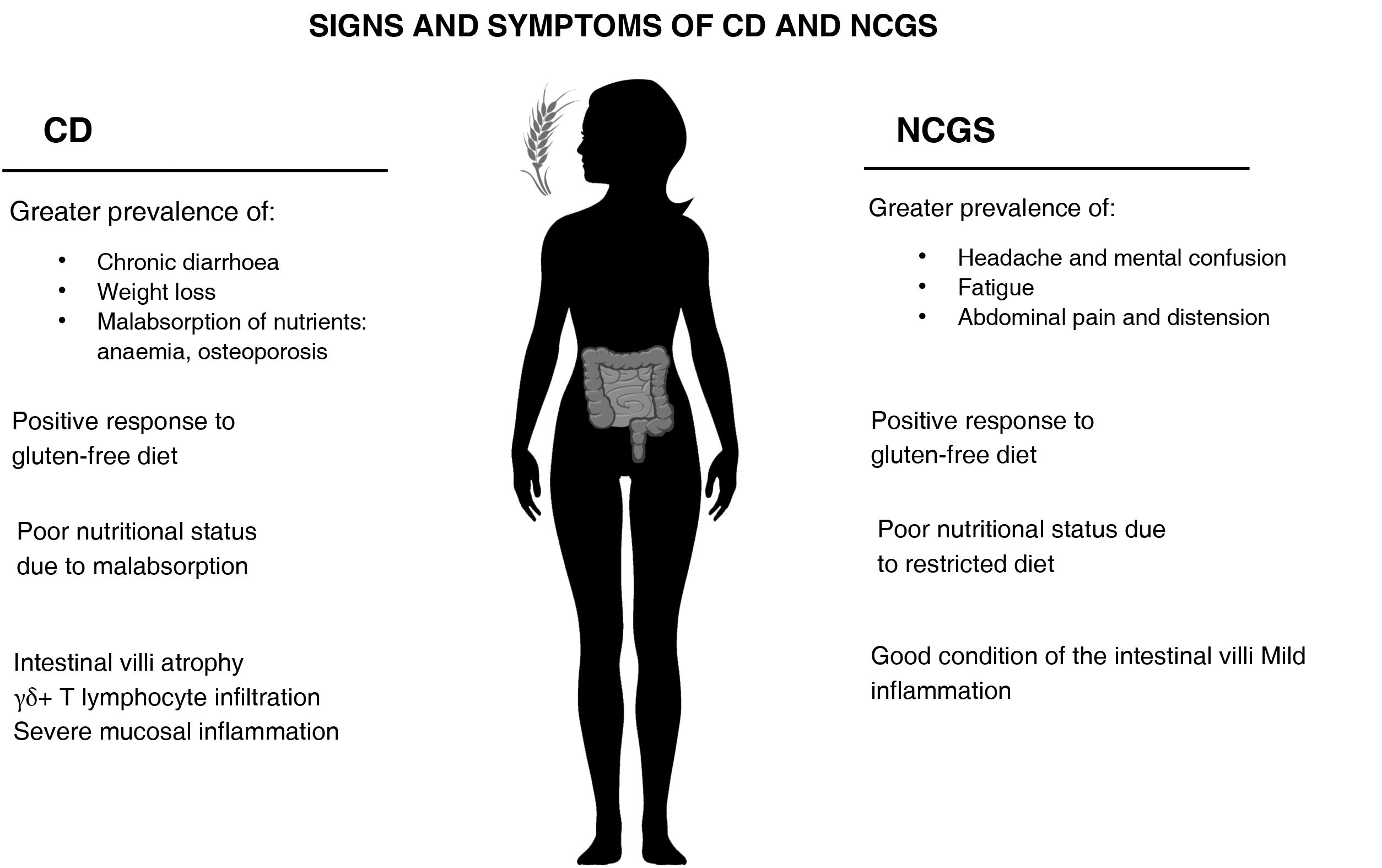

Non-coeliac gluten sensitivity and coeliac diseaseFrom a clinical standpoint, as the manifestations of CD and NCGS are similar, the differential diagnosis can be challenging in certain circumstances7,11 and lead to patients with NCGS being misdiagnosed with CD.9 A positive response to a GFD is common in both CD and NCGS.9,24 However, in the initial diagnosis, differences have been found in the prevalence of intestinal and extraintestinal symptoms (Fig. 1); NCGS had a higher prevalence of episodes of abdominal pain and distension, as well as fatigue, headache and mental confusion1; meanwhile, in CD there is a greater prevalence of nutritional deficiencies associated with nutrient malabsorption, such as anaemia and osteoporosis, as well as chronic diarrhoea and weight loss.1,9,25 Moreover, when gluten was reintroduced into the diet of NCGS patients, they developed more severe musculoskeletal, cardiovascular and gastrointestinal symptoms than the CD patients or healthy controls.26 However, that study should be interpreted with caution, as it only included CD patients who did not have severe symptoms and the NCGS subjects did not have a confirmed diagnosis.

In terms of genetic factors, an association between the HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8genotypes and the risk of suffering CD is widely accepted,9,15,27 being present in 95% of CD patients. However, such an association with the detection of NCGS is not clear. On the one hand, a prevalence of HLA-DQ2 and DQ8 has been detected in NCGS subjects ranging from 32%11 to 53%,9 and some studies suggest the detection of HLA-DQ2 and DQ8 as a possible marker for NCGS.22,27 Other studies, however, have proposed the absence of this genotype as a diagnostic factor in patients with NCGS,9,11 based on the fact that the prevalence of this type of genotype in the general population (30–40%) is similar to, or only slightly lower than, that found in patients with NCGS. The somewhat higher values in patients with NCGS could be due to a selection bias, as 12% to 25% of patients with NCGS have first- or second-degree relatives with CD, and so with HLA-DQ2 and DQ8 genotype,9,11,15,28 and that could mean they are more likely to consult a doctor and more likely to be diagnosed.

Another of the big differences between CD and NCGS is the state of the intestinal villi. In the case of NCGS patients, the villi are usually in good condition. In fact, there is broad consensus in the literature that they are normal in more than half the patients.11,15,29,30 In a very recent study, no differences were found in the serum levels of markers of epithelial damage (occludin, claudin-1, lipopolysaccharide-binding protein, intestinal fatty acid-binding protein, peptides of the zonulin family) between patients with NCGS and healthy controls.31 One possible explanation is the lesser degree of inflammation found in patients with NCGS compared to those with CD. Immunohistochemical studies of the intestinal mucosa showed that patients with NCGS had greater production of some cytokines than controls, but less than patients with CD.32,33 Similarly, a recent study carried out with transmission electron microscopy did report a certain degree of damage to the intestinal barrier in patients with NCGS compared to healthy controls,34 but to a lesser degree than in patients with untreated CD. As far as the authors of this review have been able to ascertain, only one study has shown similar levels of intestinal permeability between patients with NCGS and active CD, with both being greater than those of healthy controls.35 In any event, it should be stressed that this was an ex vivo study with a small sample size (n=6 for each arm) performed with duodenal biopsy explants in which intestinal permeability was measured after incubation with gliadin.

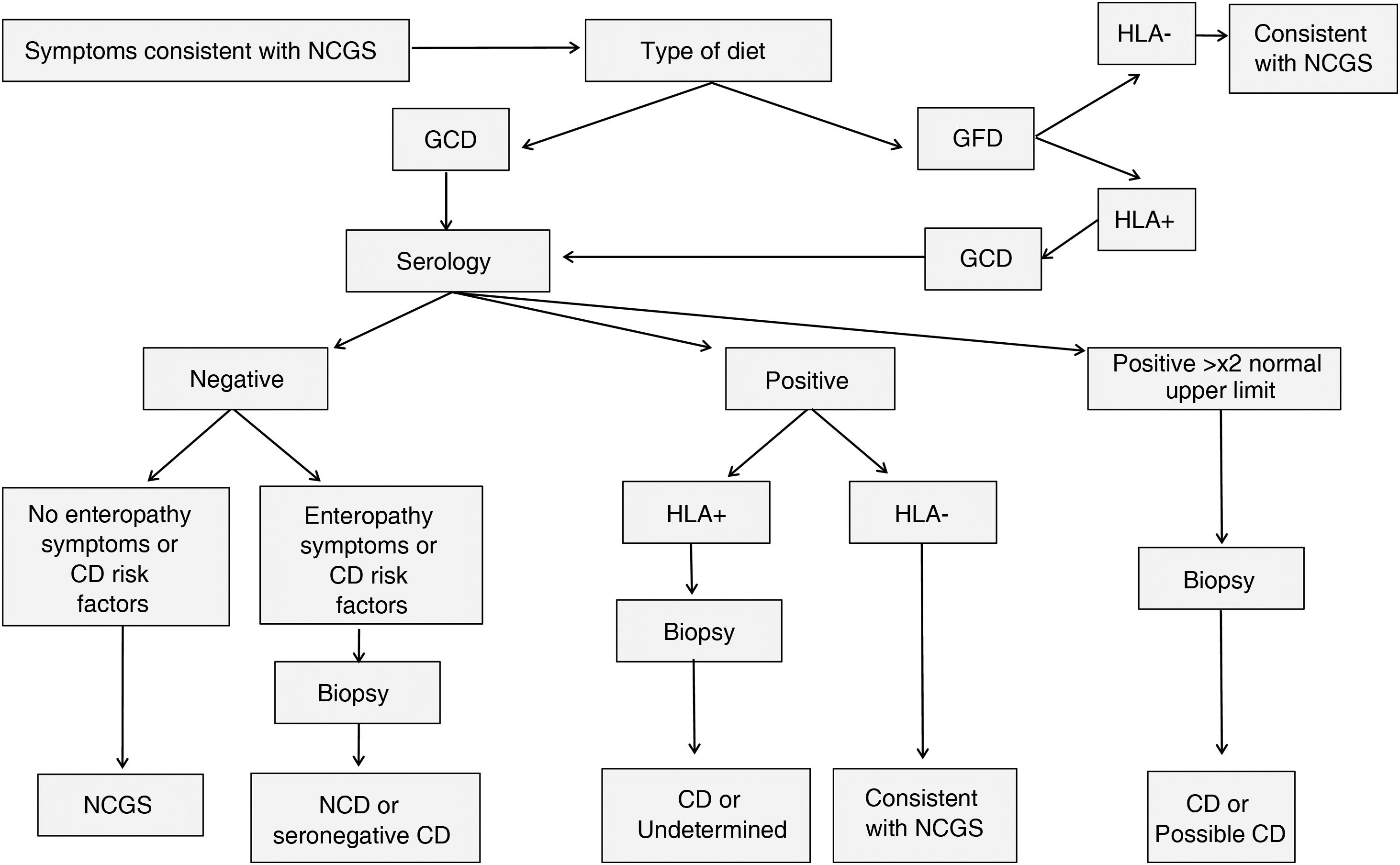

A summary of a proposed model for the differential diagnosis of CD and NCGS, which attempts to minimise the number of invasive tests, is shown in Fig. 2 and Table 1, adapted from that proposed by Kabbani et al.9 The protocol varies according to the patient’s diet. If they are not yet following a GFD, diagnosis begins with a CD serological test, which detects anti-tissue transglutaminase IgA antibodies or anti-deamidated gliadin peptide IgA/IgG antibodies. It is estimated that in the region of 2-15% of CD patients have negative serology.36 Negative serology for anti-tissue transglutaminase IgA antibodies and variable results for anti-deamidated gliadin peptide IgA/IgG antibodies have been reported in NCGS (reviewed in Elli et al.37 and detailed in the Histology section associated with NCGS). Depending on the result, three diagnostic strategies are followed; values which are twice the upper normal range are considered consistent with CD and a biopsy is performed to confirm the diagnosis. With positive serology, but not as high as twice the normal range, the HLA-DQ2 and DQ8 genotypes are tested for and are consistent with NCGS if not detected. Patients with negative serology and the absence of CD risk factors, plus no symptoms consistent with enteropathy, are diagnosed as NCGS with a diagnostic specificity of 100% and a positive likelihood ratio of 80.9%. Lastly, if the patient had already started on a GFD, an analysis of the genotype associated with CD is performed, with absence of HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8 pointing to a diagnosis consistent with NCGS. Following this model, the authors found a high specificity in the diagnosis, which in certain cases avoided the need for an endoscopy in diagnosing NCGS.

Flow chart of diagnostic tests to differentiate NCGS from CD.

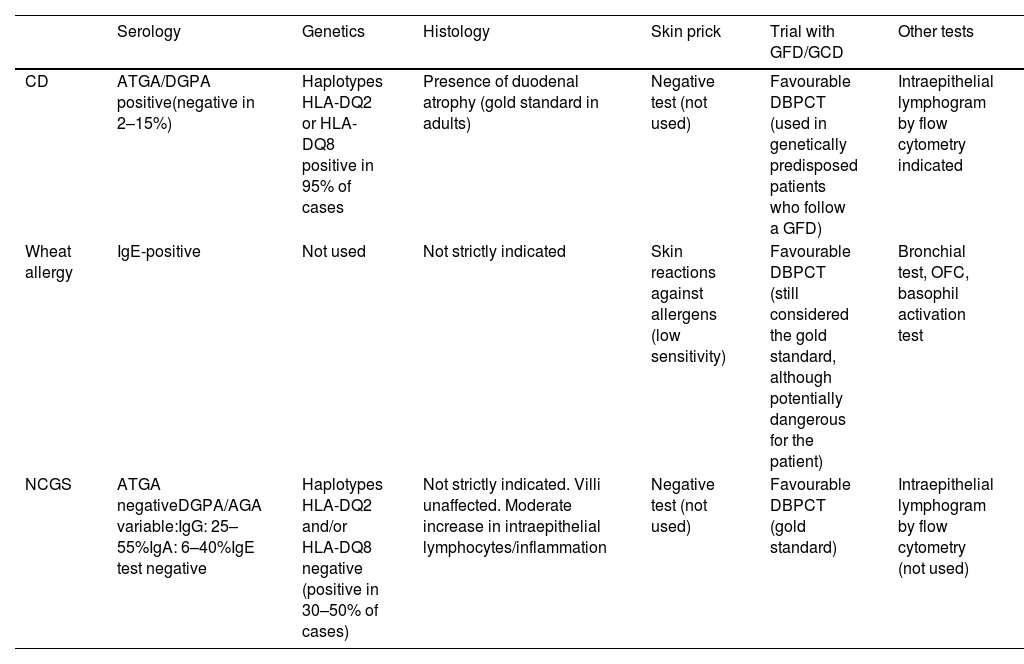

Diagnostic tests for gluten-related disorders.

| Serology | Genetics | Histology | Skin prick | Trial with GFD/GCD | Other tests | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD | ATGA/DGPA positive(negative in 2–15%) | Haplotypes HLA-DQ2 or HLA-DQ8 positive in 95% of cases | Presence of duodenal atrophy (gold standard in adults) | Negative test (not used) | Favourable DBPCT (used in genetically predisposed patients who follow a GFD) | Intraepithelial lymphogram by flow cytometry indicated |

| Wheat allergy | IgE-positive | Not used | Not strictly indicated | Skin reactions against allergens (low sensitivity) | Favourable DBPCT (still considered the gold standard, although potentially dangerous for the patient) | Bronchial test, OFC, basophil activation test |

| NCGS | ATGA negativeDGPA/AGA variable:IgG: 25–55%IgA: 6–40%IgE test negative | Haplotypes HLA-DQ2 and/or HLA-DQ8 negative (positive in 30–50% of cases) | Not strictly indicated. Villi unaffected. Moderate increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes/inflammation | Negative test (not used) | Favourable DBPCT (gold standard) | Intraepithelial lymphogram by flow cytometry (not used) |

AGA: anti-gliadin IgA antibodies; ATGA: anti-transglutaminase IgA antibodies; CD: coeliac disease; DBPCT: double-blind placebo-controlled trial; DGPA: anti-deamidated gliadin peptide IgA/IgG antibodies; GFD: gluten-free diet; NCGS: non-coeliac gluten sensitivity; OFC: oral food challenge.

Other gluten-related disorders that have to be excluded for the differential diagnosis of NCGS are wheat allergy and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Wheat allergy represents another type of adverse immune reaction to the ingestion of proteins found in wheat and other cereals. IgE mediate the inflammatory response to different allergenic proteins (alpha-amylase/trypsin inhibitor, non-specific lipid transfer protein, high molecular weight gliadins and glutenins).37,38 Diagnosis of this disease is usually based on a skin prick test, an IgE antibody test, and functional tests, such as the baker's bronchial asthma test, double-blind placebo-controlled trial or oral food challenge. However, none of them is without its drawbacks. The first two have an unsatisfactory diagnostic predictability. Meanwhile, the functional tests have a risk of severe reactions, as well as the difficulty in using them in daily clinical practice.37 The basophil activation test by flow cytometry has emerged as an alternative; this is a functional in vitro technique increasingly used for diagnosing food allergies.37,39

The symptoms of NCGS also overlap with those of IBS,23,40 a complex, multifactorial condition that is sometimes difficult to diagnose, as it can be confused with atypical or attenuated forms of inflammatory bowel disease or CD.28 IBS is characterised by recurrent abdominal pain associated with a change in bowel habits, frequent abdominal distension and bloating, with the onset of symptoms at least six months before diagnosis.41–43 The Rome IV criteria are currently used for diagnosing IBS,43 and include recurrent abdominal pain at least one day a week in the last three months, with two or more of the following characteristics: 1) Associated with defecation; 2) Related to a change in stool frequency; and 3) Related to a change in stool consistency.

Histology associated with non-coeliac gluten sensitivityThere is, as yet, no rigorous histological indicator for the diagnosis of NCGS. Duodenal biopsy is considered useful to confirm seronegative CD, but not for diagnosing NCGS because, as previously mentioned, the intestinal architecture is intact in most patients. It has also been reported that an immunohistochemical study of the mucosa may facilitate the detection of more cases of CD,44 but not of NCGS.45 However, the immunohistochemical findings in NCGS are much disputed, as there have been studies showing certain immune activation in the mucosa of these patients.30,32,33,46 It may be that the immune activation is lineage-specific and depending on the markers analysed in the study, it is either detected or not. For example, no differences have been found in the mucosal expression of IL-17A47, IL-6, IL-8, IL-2 and IFN-©32,33 between patients with NCGS and controls, but differences were found in the expression of TNF, IL-1®, IL-12 and IL-15.32 It is interesting to note, however, that after gluten intake, patients with NCGS do respond with greater expression of IFN-© in the rectal mucosa.33,48 This highlights the importance of selecting patients with a proper diagnosis and who are in the same condition in terms of gluten intake.

Regarding the infiltration of intraepithelial lymphocytes, results in the scientific literature are contradictory, with some studies showing that there are no differences32 in the lymphocyte count between patients with NCGS and healthy controls and other that there are.33 This suggests that, although flow cytometry of duodenal biopsy49 appears to be very useful in confirming the diagnosis of CD,36,50 as there is a profile in these patients with a predominance of T lymphocytes with γδ+ receptor,51 more studies are required to confirm its utility in the diagnosis of NCGS; especially considering that these techniques are not cost-effective for differential diagnosis in the case of patients with a negative genetic test, as CD is practically ruled out.36

Lastly, in the histological assessment during investigation of a patient with suspected NCGS, it is also essential to rule out other possible causes of increased intraepithelial lymphocytes without alteration of the villi, such as infection caused by Helicobacter pylori, Giardia lamblia or Cryptosporidium (reviewed in Brown et al.52).

Biomarkers for non-coeliac gluten sensitivityThe lack of full understanding of the pathophysiology and aetiology of NCGS,53 the limitations of the Salerno protocol for diagnosing the condition,19 and the clinical similarities with other disorders with which the diagnosis can be confused, make it essential to search for specific and discriminative biomarkers for NCGS.27

Anti-gliadin antibodiesGliadin, one of the proteins that makes up gluten,54 is recognised as a trigger for CD and NCGS symptoms. However, there are conflicting results as to how useful anti-gliadin antibodies (AGA) are in the diagnosis of NCGS. On the one hand, subjects diagnosed with NCGS have been found to be positive for these antibodies, with prevalences in the range of 6-40% for AGA-IgA and 25-55% for AGA-IgG.12,23 The positivity rate among patients with NCGS has also been found to be higher than among others with non-gluten-related microscopic enteritis.55 On the other hand, however, differences found when comparing the positivity of these antibodies in patients with NCGS to healthy controls were not significant (17.9% vs 12.5%).24 Similarly, low sensitivity (59.3% AGA-IgA; 83.1% AGA-IgG) and specificity (61.8% AGA-IgA; 42.6% AGA-IgG) were found for AGA as a diagnostic marker for NCGS.27

There may be several reasons for the lack of consistency in these results, including different sample size, the inclusion and exclusion criteria used by the researchers and varying degrees of adherence to the Salerno protocol for diagnosis.11 For example, in the multicentre study by Volta et al with 486 participants, a low prevalence of positive anti-AGA antibodies was found, but many of the patients were already on a GFD.11 Furthermore, Caio et al studied the effect of a six-month GFD in 44 patients with NCGS, with positive baseline levels for AGA-IgG. After follow-up, only three of them (6.8% of the cohort) still had positive AGA-IgG levels, correlating with their poor adherence to the diet.56 However, in the CD group, AGA-IgG levels were maintained after the GFD period, regardless of adherence or clinical response.

ZonulinGliadin is responsible for the release of zonulin, a single-chain protein that acts on epithelial cells, increasing intestinal permeability.29 Elevated zonulin levels were found in patients with NCGS and CD, compared to asymptomatic controls and patients with irritable bowel syndrome.29 The effect of abstaining from gluten on zonulin levels was also studied, but the reduction was not significant.29 In the same study, a positive correlation was found between zonulin serum levels and symptoms of abdominal pain, severity and frequency of abdominal distension and anxiety, and an inverse correlation with quality of life. In addition, its validity as a diagnostic marker was high, with an area under the curve of 0.865, with a specificity of 88% for a maximum serum concentration of 10.3–10.7pg/ml.29

ALCAT testALCAT 5 is an in vitro test in which neutrophils are exposed to extracts of gluten-containing cereals (wheat, rye, barley and oats) in order to measure their toxic effect on the cells. When the size, volume or shape of the neutrophils change from baseline, the test is considered positive. This test was carried out on 25 subjects with abdominal symptoms, 13 of whom were diagnosed with NCGS following the Salerno protocol. The ALCAT 5 test had a sensitivity of 81% and a specificity of 22.2%, with a positive predictive value of 65% and a negative predictive value of 40%. These results show the value of this test as a complement when NCGS is suspected clinically, but the study was severely limited by the lack of a healthy control group.21

Micro-RNAMicro-RNA (miRNA) are short RNA sequences involved in the regulation of gene expression and in the control of cell functions. Clemente et al.17 recently identified seven differential miRNA in duodenal biopsies whose expression in patients with NCGS is greater than that found in those with CD. Of these, hsa-miR-19b-3p and hsa-miR-30e-5p had the highest predictive value. Using only the first marker, 70.4% of the patients were reclassified into the NCGS group. In turn, hsa-miR-30e-5p was the most predictive in the differential diagnosis of NCGS and CD as, based on its expression, 74.1% of the patients were included in the NCGS group.

Impaired immune tolerance has been suggested as a cause of NCGS, due to an increased inflammatory response mediated by miRNA.17 Continuing with this hypothesis, other studies have also linked autoimmune diseases with NCGS, finding coexistence of both in 14% of patients.11

Long noncoding RNA (LncRNA)With the aim of expanding the biomarkers for the diagnosis of NCGS, Efthymakis et al.18 identified 300 RNA sequences differentially expressed in the intestinal mucosa of patients with NCGS compared to controls. Most of these sequences corresponded to LncRNA and to a lesser extent to protein-encoding RNA. The functions of LncRNA are not yet fully understood; the authors suggest that they may be involved in both inflammatory responses and in the modulation of the immune system, so their expression may be altered in autoimmune diseases. This study gives further strength to the role of the immune system in NCGS.18

Differential cytokines in non-coeliac gluten sensitivityMasaebi et al.57 propose using the cytokines measured in serum as biomarkers in the diagnosis of CD and NCGS. They found IL-8 to be the cytokine with the highest positive predictive value in distinguishing CD from NCGS. This is consistent with other studies that showed that, of the multiple cytokines analysed, IL-8 was the only one with a higher concentration in patients with CD than in those with NCGS,58 with no differences in serum levels of this cytokine between patients with NCGS and healthy controls.31 Furthermore, another immunohistochemical study found the same result for the analysis of IL-8 expression in mucosa.33

Another inflammatory cytokine possibly associated with NCGS is CXL10. The in vitro study by Valerii et al.,59 which peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with NCGS were cultured with protein extracts from different cereals, found an increase in CXL10 secretion. However, the data from this study were not homogeneous, either in terms of patients with NCGS or in controls, and only this cytokine was analysed.

Signs and symptoms in patients with non-coeliac gluten sensitivityGastrointestinal symptomsPatients diagnosed with NCGS suffer from intestinal symptoms, with more than half suffering from two or more; abdominal pain is the most common, affecting 33% to 84.1% of patients.1,11,16,24,30 Other common gastrointestinal symptoms are abdominal distension, diarrhoea, constipation, gas or flatulence and epigastric pain.16,23,24,30

With regard to which symptoms are perceived as more severe by patients, Elli et al found that the most severe (on a scale of 1 to 10) were abdominal distension (8.2±2.8), postprandial fullness (6.6±3.0), early satiety (6.4±2.8) and abdominal pain (5.4±2.4).20 A cross-over double-blind trial of GCD/GFD in patients diagnosed with NCGS conducted by Zanini et al found that those who correctly identified the gluten-containing diet based on their symptoms described their symptom severity (measured with the GSRS, from 1 to 7) as follows: indigestion, 3.2±1.1; diarrhoea, 2.9±1.5; constipation, 2.9±1.3; pain, 2.6±1.0; and reflux, 2.2±0.9.14

Extraintestinal symptomsThese are common in patients diagnosed with NCGS, with reported rates of 76%15 up to 100%.1 The most common are fatigue, mental confusion and headache.1,11,24,29 General malaise, anxiety/depression and joint pain have also been reported1,7,11,16,30 and it is believed that psychological or psychosomatic factors such as anxiety or depressive symptoms could also affect the intestinal symptoms.26

Time of onset of symptoms after gluten intakeVolta et al reported that in more than half of patients with NCGS, the symptoms occurred within six hours of gluten intake; in approximately 40%, between six and 24h after; and in less than 10%, 24h after.11 These data are consistent with the study by Croall et al in which the symptoms appeared during the first 12h after gluten intake in 87% of the patients.24

Nutritional statusThe nutritional status of patients with NCGS can be affected. In patients with suspected NCGS, low levels of ferritin, folic acid and vitamin D have been found in 23%, 5% and 11%, respectively, while 24% of patients had anaemia, in the majority of cases caused by iron deficiency.11 In another study, 18.4% of the patients with NCGS had some type of nutrient deficiency.9 In addition to this, 35% of patients with NCGS were estimated to have weight loss.22 It is important to highlight that the frequent weight loss and some of the nutritional deficiencies that occur in patients with NCGS are caused by the restricted diet and exclusion of foods they subject themselves to, as in NCGS there is no malabsorption of nutrients, because the architecture of the intestinal epithelium is maintained. These dietary treatments should therefore be prescribed and monitored by healthcare professionals.22,23

ConclusionsPatients with NCGS are a heterogeneous group in which interindividual differences have been observed, but in which abdominal pain and fatigue are the most common symptoms. The heterogeneity in the response to a GFD also raises the suspicion of other possible aetiopathogenic mechanisms, including a possible response to other components of wheat, such that the term "non-coeliac wheat sensitivity" is beginning to replace NCGS. The protocol for the diagnosis of NCGS standardised by the Salerno experts has shown contradictory results in various studies, especially in the blind response to gluten. Nevertheless, it remains the best diagnostic criterion to date, even though given its complexity it can only be implemented in research and not in clinical practice. Of all the biomarkers analysed in various studies, there is a broad consensus that elevated IL-8 values can distinguish patients with CD from those with NCGS. However, at present there are no serological or genetic clinical laboratory procedures for the diagnosis of NCGS, and it remains limited to a diagnosis of exclusion. New studies are needed to learn more about this disease, its diagnosis and its treatment, in order to improve the quality of life of these patients.

Ethical responsibilitiesThis study has no ethical considerations as it is a review.

FundingThe study was conducted without any funding.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.