Despite novel medical therapies, colectomy has a role in the management of patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) and inflammatory bowel disease unclassified (IBDU). This study aimed to determine the incidence of unplanned surgery and initiation of immunomodulatory or biologic therapy (IMBT) after colectomy in patients with UC or IBDU, and identify associated factors.

MethodsData of patients with preoperative diagnosis of UC or IBDU who underwent colectomy and were followed up at a single tertiary centre was retrospectively collected. The primary outcome was the risk of unplanned surgery and initiation of IMBT during follow-up after colectomy. Secondary outcomes were development of Crohn's disease-like (CDL) complications and failure of reconstructive techniques.

Results68 patients were included. After a median follow-up of 9.9 years, 32.4% of patients underwent unplanned surgery and IMBT was started in 38.2%. Unplanned surgery-free survival was 85% (95% confidence interval [CI] 73.8–91.6%) at 1 year, 76% (95% CI 63.2–84.9%) at 5 years and 69.1% (95% CI 55–79.6%) at 10 years. IMBT-free survival was 96.9% (95% CI 88.2–99.2%) at 1 year, 77.6% (95% CI 64.5–86.3%) at 5 years and 63.3% (95% CI 48.8–74.7%) at 10 years. 29.4% of patients met criteria for CDL complications. CDL complications were significantly associated to IMBT (hazard ratio 4.5, 95% CI 2–10.1).

ConclusionIn a retrospective study, we found a high incidence of unplanned surgery and IMBT therapy initiation after colectomy among patients with UC or IBDU. These results further question the historical concept of surgery as a “definitive” treatment.

La colectomía continúa teniendo un rol terapéutico en pacientes con colitis ulcerosa (CU) y enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal no clasificada (EII-noC). El objetivo de este estudio fue determinar la incidencia de cirugía no planificada e inicio de terapias inmunomoduladoras/biológicas (TIMB) tras colectomía en pacientes con CU o EII-noC, e identificar factores de riesgo.

MétodosSe analizaron retrospectivamente los datos de pacientes con CU o EII-noC y colectomía seguidos en un centro terciario. El objetivo primario fue evaluar el riesgo de reintervención e inicio de TIMB. Los objetivos secundarios fueron analizar la incidencia de Crohn “de novo” y el fracaso de las técnicas reconstructivas.

Resultados68 pacientes fueron incluidos. Tras una mediana de seguimiento de 9.9 años, el 32.4% de los pacientes fueron reintervenidos y el 38.2% inició TIMB. La supervivencia libre de reintervención fue 85% (intervalo confianza 95% [IC] 73.8-91.6%) al año, 76% (IC 95% 63.2-84.9%) a los 5 años y 69.1% (IC 95% 55-79.6%) a los 10 años. La supervivencia libre de TIMB fue 96.9% (IC 95% 88.2-99.2%) al año, 77.6% (IC 95% 64.5-86.3%) a los 5 años y 63.3% (IC 95% 48.8-74.7%) a los 10 años. 29.4% de los pacientes cumplieron criterios de Crohn “de novo”. Crohn “de novo” fue factor de riesgo para inicio de TIMB (Hazard ratio 4.5%, IC 95% 2-10.1).

ConclusiónEn una cohorte retrospectiva, encontramos una alta incidencia de cirugía e inicio de TIMB tras colectomía en CU o EII-noC. Estos resultados cuestionan el concepto clásico de colectomía como tratamiento definitivo.

In recent decades, the risk of colectomy in patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) has decreased, probably as a result of the introduction of novel medical therapies.1 A recent systematic review reported a pooled rate of colectomy of 10% at 5 years of diagnosis.2 However, surgery still has a role in the management of patients refractory to medical treatment, and may be an appropriate strategy in those at risk of neoplastic transformation. On the other hand, disease complications such as toxic megacolon, perforation or severe haemorrhage are indications for urgent surgery.3

According to patient characteristics and indication for surgery, different surgical procedures may be performed. Total proctocolectomy (TPC), either with ileostomy or intestinal restoration with an ileal pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA), has historically been considered as the surgical procedure of choice, and has even been hailed as the cure of UC.4,5 Good outcomes in terms of quality of life have been reported in both cases.6 Subtotal colectomy (STC) with ileorectal anastomosis (IRA) can be an alternative in selected patients with mild rectal activity.7

However, regardless of the type of surgery, we have addressed in our clinical practice as gastroenterologists a need for relevant medical interventions, such as immunomodulatory and/or biologic therapy or new unplanned surgical procedures, during post-colectomy follow-up in a number of patients. This fact leads to reconsideration of the concept of proctocolectomy as a “definitive” treatment in UC.

Immunomodulators and/or biologics may be necessary in case of refractory chronic pouchitis or severe proctitis among patients with IPAA or IRA, respectively.8,9 Moreover, up to 25% of patients may develop Crohn's disease-like (CDL, as defined below) complications after colectomy, and the threshold to initiate immunomodulators or biologics is low.10 Although this entity is better characterized in the subgroup of patients with an ileal pouch,11,12 it has also been described among those with TPC and terminal primary ileostomy.13

Regarding need for unplanned surgery, approximately 25% of patients present with small bowel obstruction after diverting loop ileostomy. Failure to conservative treatment occurs in 25% of those, leading to surgery.14 On the other hand, pouch failure resulting in permanent ileostomy or pouch excision affects 10–20% of patients at 10 years,15,16 while failure of IRA has been reported to occur in up to 24% of patients at 10 years, mainly due to refractory proctitis.9

The aim of this study is to describe the incidence of major events, such as surgical reintervention or initiation of immunomodulatory or biologic therapy (IMBT), after colectomy in a cohort of patients with preoperative diagnosis of UC or inflammatory bowel disease unclassified (IBDU), and to identify associated factors.

Materials and methodsStudy design and patient populationWe performed a retrospective, observational, cohort study in a single Spanish tertiary centre with an Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) Unit certified by Bureau Veritas and by the Spanish IBD Study Group (GETECCU) and with an Advanced Colorectal Surgery Unit, accredited by the Spanish Colorectal Surgery Society (AECP). Patients were included if they met the following criteria: (1) Preoperative diagnosis of UC or IBDU according to the “European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation” criteria.17 (2) Colectomy (TPC+permanent ileostomy, TPC+IPAA, STC+ileostomy, STC+IRA) due to disease activity or its complications. (3) Follow-up after surgery at the IBD Unit associated to the Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology in Ramón y Cajal University Hospital.

Patients were excluded if the follow-up after colectomy was<3 months.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee at Ramón y Cajal University Hospital (Madrid, Spain) on April 25th, 2019. Informed consent was waived by the Ethics Committee.

Outcomes and definitionsThe primary outcome was the proportion of patients with major events after colectomy, including initiation of IMBT and unplanned surgery (which specifically excluded surgery to complete proctectomy as a step to bowel restoration or to primarily restore intestinal continuity, ileostomy closure, abdominal surgery not associated to IBD or colectomy and perianal surgery). Secondary outcomes were: (1) Assessment of patients with CDL complications, defined as non-anastomotic stricture, non-anastomotic fistula diagnosed>3 months after surgery or prepouch ileitis during post-colectomy follow-up, and without Crohn histology in colectomy specimen. (2) Proportion of patients with failure of intestinal continuity restoration (deconstruction of IRA, pouch excision, permanent ileostomy). (3) Identification of factors independently associated to major events.

Data collectionPatients with a diagnosis of UC/IBDU who underwent colectomy between July 1984 and March 2020 were identified. Follow-up started at the time of colectomy and ended June 2020, if there were no events. Data were retrospectively extracted from the medical records. Baseline data included age, sex, type of IBD, date of diagnosis, location of the disease and medical therapy before colectomy. The date of colectomy, type of surgery, post-operative complications, type of intestinal restoration, Crohn histology in colectomy specimen, post-operative fistulae, strictures or prepouch ileitis, and data on surgical reinterventions and medical therapy during the post-colectomy follow-up were recorded.

Statistical analysisDescriptive data were presented as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) and proportions. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to assess cumulative unplanned surgery-free and IMBT-free survival separately. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis were performed to identify factors associated with major events, expressed as hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Variables for the univariate analysis were chosen a priori based on previous knowledge and pathophysiological backgrounds (age, sex, previous thiopurines, previous biologic therapy, urgency for colectomy, initial ileostomy, pouch and CDL complications). We considered variables with a p value<0.1 for multivariate selection modelling via backward stepwise regression. The proportion hazards assumptions was tested by Schoenfeld residuals. The analyses were carried out using Stata version 14. p<0.05 was considered significant.

ResultsPatient characteristicsSixty-nine patients with a diagnosis of UC or IBDU underwent colectomy and fulfilled the inclusion criteria. One patient died in the early post-colectomy period due to surgical complications and 68 patients were finally included.

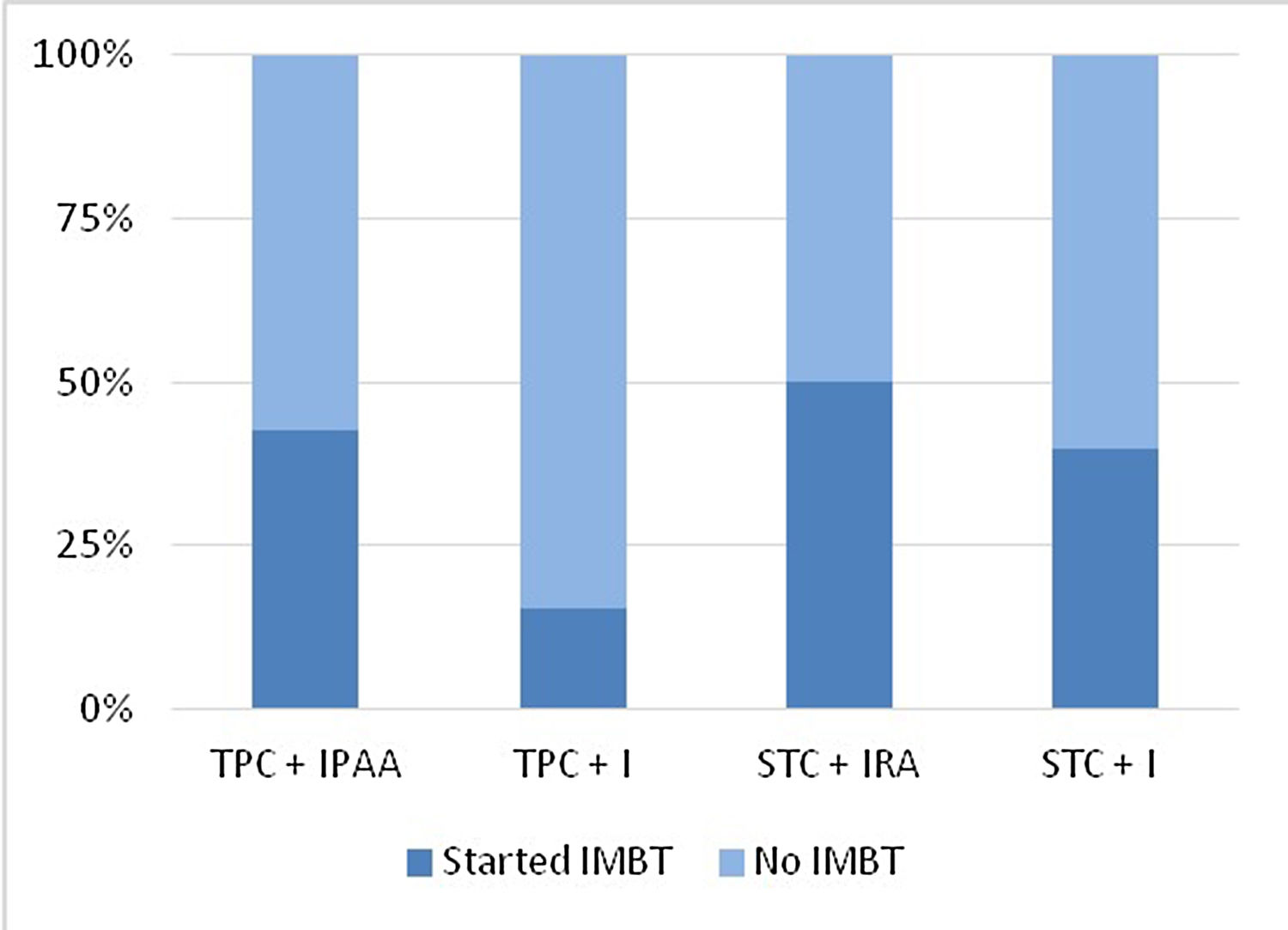

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the total series are summarized in Table 1. Thirty-seven patients (54.4%) were male and the median age at diagnosis was 37 years (interquartile range [IQR]: 26.7–46). Sixty-five patients (95.6%) were initially diagnosed with UC and 49 (72%) had pancolitis. Five patients (7.4%) had perianal disease. Twenty-nine patients (42.6%) had received thiopurines, 28 (41.2%) had been treated with anti-tumour necrosis factor (anti-TNF), 7 (10.3%) with vedolizumab and 5 (7.4%) with tofacitinib prior to colectomy. Among patients who received biologic therapy, 20 (29.4%) received one agent, one (1.5%) received two and 7 (10.3%) received more than two biologic agents. Median age at colectomy was 41 years (IQR: 32–50) and median time from diagnosis of IBD to colectomy was 40.5 months (IQR: 7–84). Colectomy was due to medical therapy-refractory disease in 45 patients (66.2%) and to perforation, toxic megacolon, dysplasia/colorectal cancer (CRC), stenosis and haemorrhage in 12 (17.6%), 4 (5.9%), 3 (4.4%), 2 (2.9%) and 2 (2.9%) patients, respectively. Colectomy was performed in an urgent setting in 29 patients (42.6%). A TPC+IPAA was performed in 40 patients (58.8%) as the initial surgical option, a TPC+permanent ileostomy in 13 (19.1%), a STC+IRA in 10 (14.7%) and a STC+ileostomy in 5 (7.4%). Fifty-four (91.5%) patients had an ileostomy constructed at the time of colectomy. Sixteen (23.5%) patients had early post-colectomy complications.

Baseline characteristics of patients with UC or IBDU and colectomy.

| N=68 | |

|---|---|

| Gender (male) | 37 (54.4%) |

| Initial diagnosis | |

| UC | 65 (95.6%) |

| IBDU | 3 (4.4%) |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 37 (26.7–46) |

| Extent of disease | |

| Pancolitis (E3) | 49 (72%) |

| Left-sided colitis (E2) | 18 (26.5%) |

| Proctitis (E1) | 1 (1.5%) |

| Perianal disease | 5 (7.4%) |

| Previous medical therapy | |

| Thiopurines | 29 (42.6%) |

| Anti-TNF | 28 (41.2%) |

| Vedolizumab | 7 (10.3%) |

| Tofacitinib | 5 (7.4%) |

| Number of biologic agents received | |

| 0 | 40 (58.9%) |

| 1 | 20 (29.4%) |

| 2 | 1 (1.5%) |

| >2 | 7 (10.3%) |

| Age at colectomy (years) | 41 (32–50) |

| Time diagnosis-colectomy (months) | 40.5 (7–84) |

| Indication for colectomy | |

| Refractoriness to medical treatment | 45 (66.2%) |

| Perforation | 12 (17.6%) |

| Toxic megacolon | 4 (5.9%) |

| Dysplasia or CRC | 3 (4.4%) |

| Stenosis | 2 (2.9%) |

| Haemorrhage | 2 (2.9%) |

| Urgent colectomy | 29 (42.6%) |

| Type of initial surgery | |

| TPC+IPAA | 40 (58.8%) |

| TPC+PI | 13 (19.1%) |

| STC+IRA | 10 (14.7%) |

| STC+I | 5 (7.4%) |

| Initial ileostomy | 54 (91.5%) |

| Early post-operative complications | 16 (23.5%) |

UC: ulcerative colitis, IBDU: inflammatory bowel disease unclassified, CRC: colorectal cancer, TPC+IPAA: total proctocolectomy+ileal pouch-anal anastomosis, TPC+PI: total proctocolectomy+permanent ileostomy, STC+IRA: subtotal colectomy+ileorectal anastomosis, STC+I: subtotal colectomy+ileostomy.

Median follow-up after colectomy was 9.9 years (5.4–19.6).

Major events after colectomy- •

Unplanned surgical reintervention

Unplanned surgery was performed in 22 patients (32.4%). According to type of colectomy-related surgery, 30% of TPC+IPAA, 30.7% of TPC+permanent ileostomy, 40% of STC+IRA and 40% of STC+ileostomy patients were reoperated at some time after colectomy (Fig. 1). Surgical reintervention-free survival after colectomy was 85% (95% CI 73.8–91.6%) at 1 year, 76% (95% CI 63.2–84.9%) at 5 years and 69.1% (95% CI 55–79.6%) at 10 years for the whole cohort (Fig. 2). Nine of 22 reoperated patients (40.9%) required more than one reintervention. Indication for surgery was stricture or obstruction in 9 patients (40.9%), fistula or abscess in 8 (36.4%), eventration in 4 (18.2%), failure of medical treatment in 4 (18.2%), perforation in 2 (9%), haemorrhage in 2 (9%) and dysplasia or CRC in 1 patient (4.5%). Among the four patients with failure to medical treatment, three had an ileal pouch and were diagnosed with refractory chronic pouchitis and one had an IRA.

- •

Immunomodulatory or biologic therapy

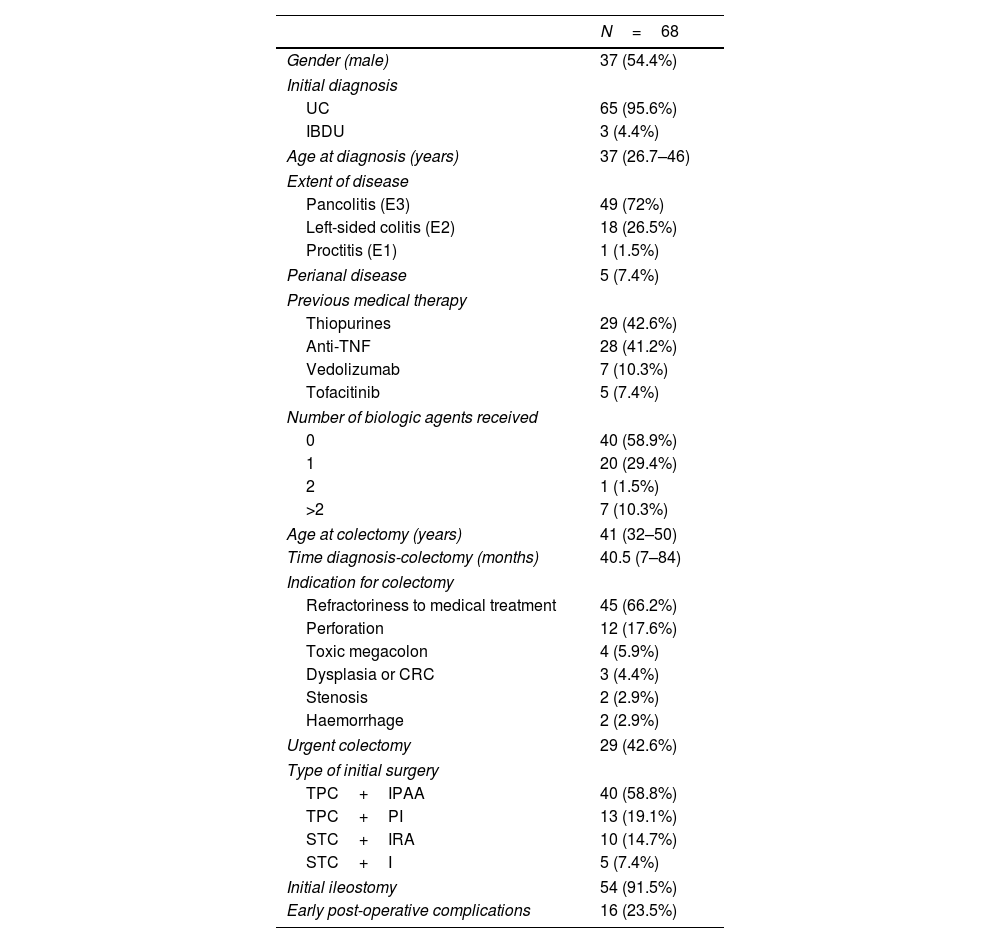

IMBT was started in 26 patients (38.2%). According to type of colectomy-related surgery, 42.5% of PCT+IPAA, 15.4% of TPC+permanent ileostomy, 50% of STC+IRA and 40% of STC+ileostomy patients started IMBT at some time after colectomy (Fig. 3). IMBT-free survival after colectomy was 96.9% (95% CI 88.2–99.2%) at 1 year, 77.6% (95% CI 64.5–86.3%) at 5 years and 63.3% (95% CI 48.8–74.7%) at 10 years for the whole cohort (Fig. 4). Eighteen patients (26.5%) started thiopurines, and 16 (23.5%), 3 (4.4%), and 2 (2.9%) started anti-TNF, methotrexate and ustekinumab, respectively.

Incidence of IMBT initiation according to type of colectomy-related surgery. IMBT: immunomodulatory and/or biologic therapy, TPC+IPAA: total proctocolectomy+ileal pouch-anal anastomosis, TPC+PI: total proctocolectomy+permanent ileostomy, STC+IRA: subtotal colectomy+ileorectal anastomosis, STC+I: subtotal colectomy+ileostomy.

Twenty patients (29.4%) met criteria for CDL complications (15 had TPC+IPAA, 75%; 4 STC+IRA, 20%; 1 TPC+permanent ileostomy, 5%). Postoperative anastomotic dehiscence occurred in one patient with IPAA (2.5%). This patient developed early peri-pouch fistulae and was reoperated twice before pouch excision and performance of permanent ileostomy. Crohn histology was found in 4 patients (5.9%) in the colectomy specimen, 3 of whom had an initial diagnosis of UC. Eight patients with CDL complications (40%) were operated and 17 (85%) started IMBT during follow-up (12 started thiopurines, 60%; 10 biologics, 50%). Among patients with IPAA and CDL complications, 3 patients (20%) had pouch failure.

Failure of intestinal continuity restorationPouch failure and failure of IRA occurred in 6 (15%) and 3 (30%) patients, respectively. Pouch excision was performed in 5 patients (12.5%). Three of 5 patients (60%) with pouch failure and 2 of 3 patients (66.7%) with failure of IRA met criteria for CDL complications, respectively.

Factors associated to major events- •

Unplanned surgical reintervention

No factors, including age, gender, previous thiopurines, urgency for colectomy, initial ileostomy, pouch and CDL complications, were significantly associated to surgical unplanned reintervention after colectomy in univariate analysis. Use of biologics prior to colectomy was not tested, as some patients underwent colectomy before their introduction in clinical practice.

- •

Immunomodulatory therapy

Results of univariate and multivariate analysis are summarized in Table 2. In multivariate analysis, only CDL complications was selected as an independent predictor of IMBT (HR 4.5, 95% CI 2–10.1, p<0.001). Additionally, we tested the role of CDL complications as a predictor of IMBT after adjusting by age and gender. The association remained significant in this analysis (HR 4.12, 95% CI 1.78–9.54, p=0.001).

Factors associated with IMBT after colectomy.

| Variable | Univariate hazard ratio (HR) | p | Age-gender adjusted HR (95% CI) | Age-gender adjusted p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.98 (0.95–1.01) | 0.26 | ||

| Male gender | 1.53 (0.70–3.34) | 0.29 | ||

| Previous thiopurines | 0.73 (0.32–1.68) | 0.46 | ||

| Pouch | 0.97 (0.43–2.18) | 0.94 | ||

| Crohn's disease-like complications | 4.50 (2.00–10.14) | <0.001 | 4.12 (1.78–9.54) | 0.001 |

The aim of this study was to ascertain the outcome after colectomy in terms of initiation of IMBT and unplanned surgery. It reports the experience in a tertiary centre with expertise in the management of IBD, after a median follow-up of nearly 10 years. During post-colectomy follow-up, nearly one third of patients required unplanned reoperation and 38.2% started IMBT based on medical criteria. Importantly, 29.4% of patients were found to have CDL complications. Failure of intestinal continuity restoration occurred in more than 10% of patients with IPAA and in 30% of patients with IRA. Need for IMBT after colectomy was significantly associated to CDL complications.

This study confirms the need for major events such as unplanned surgical reintervention or IMBT in a high proportion of patients after colectomy. A likely improvement in health-related quality of life (QoL) has previously been reported in patients with active UC after surgery.18 However, unplanned surgery or immunomodulatory therapy may negatively impact QoL but are not directly assessed in QoL questionnaires.

Unlike previous reports, this analysis includes patients with different types of transit reconstruction after colectomy. In this cohort, there was a trend towards a higher need for unplanned surgery in patients with rectum left in situ (40% for STC+IRA, 40% for STC+ileostomy) than in those with TPC (30% for IPAA, 30.7% for permanent ileostomy). Not surprisingly, the main indication for reintervention in the whole cohort was bowel obstruction, which represents one of the most common complications after both major abdominal surgery19 and ileostomy,14 which was frequently performed in this cohort.

IMBT tended to be started less frequently in patients with a TPC+permanent ileostomy (15.4%) than in those with other types of colectomy-related surgery (40%-50%). The only patient with TPC+permanent ileostomy started on IMBT was initially diagnosed of UC with perianal disease. The patient underwent colectomy due to refractoriness to medical treatment. The colectomy specimen was suggestive of UC. However, recurrent perianal disease led to a change in diagnosis to Crohn's disease and initiation of biologic therapy. As a main finding, although more patients needed IMBT than unplanned surgery during follow-up, nearly half of the patients who were reoperated underwent surgery within the first year after colectomy, which suggests a higher risk of unplanned reintervention during the “early” post-colectomy period.

Pouch failure rates were similar to other series,20 and the trend towards a higher risk of failure of IRA than IPAA in our cohort is in line with other studies.21 Surprisingly, the frequency of CDL complications was higher in our cohort than reported in previous studies.22,23 Differences in classification of CDL complications may account for some of the differences between studies. Using similar diagnostic criteria, Zaghiyan et al.24 reported a frequency of de novo Crohn's disease of 19% after a follow-up period of 76 months, without significant differences between patients with a prior diagnosis of UC or IBDU. Our longer follow-up period may partially explain the gap.

Not surprisingly, CDL complications was identified as a risk factor for post-colectomy IMBT. CDL complications are amongst the most impactful after colectomy and, in pouch carriers, may ultimately lead to pouch failure. Therefore, aggressive medical treatment with a low threshold for immunomodulators and biologics has been advocated and is common practice in this scenario.

We readily acknowledge several limitations to our study. Owing to its retrospective design, control over data collection was limited. The relatively small sample size precluded comparative analysis of results among groups of patients with different transit reconstructions after colectomy, as well as testing of relevant variables such as indication for colectomy in multivariate analysis. However, we believe this is useful initial data to inform design of larger, multi-centre studies which allow for subgroup comparisons.

In conclusion, we found a relatively high incidence of unplanned surgery and IMBT initiation after colectomy among patients with UC/IBDU, which further questions the historical concept of surgery as a “definitive” treatment in UC. The role of colectomy in the management of patients with UC and IBDU remaining key, patients need to be informed about post-colectomy outcomes in order to harbour realistic expectations, considering not only the results of studies assessing QoL but also the risk for major medical interventions such as unplanned surgery and need for immunomodulators or biologics.

Authors’ contributionLaura Núñez participated in conception and design of the analysis, collection of data and paper writing.

Francisco Mesonero participated in conception of the analysis and paper writing.

Enrique Rodríguez de Santiago performed the analysis of data.

Javier Die contributed data.

Agustín Albillos participated in conception of the analysis.

Antonio López-Sanromán participated in conception and design of the analysis and supervised paper writing.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.