Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI) is common after pancreatic surgery. In patients with chronic pancreatitis, our previous results supported the use of fecal elastase-1 (FE-1) over the 13C-mixed triglyceride breath test (13C-MTBT) for the diagnosis of EPI. However, it is poorly established how the performance of these two tests compares to the diagnosis of EPI after pancreatic surgery.

Patients and methodsFE-1 and 13C-MTBT were compared with the gold standard coefficient of fat absorption (CFA). Area under ROC curve (AUC) and best cutoffs were used to assess presence of EPI. Patient characteristics were evaluated by extent of pancreatic resection.

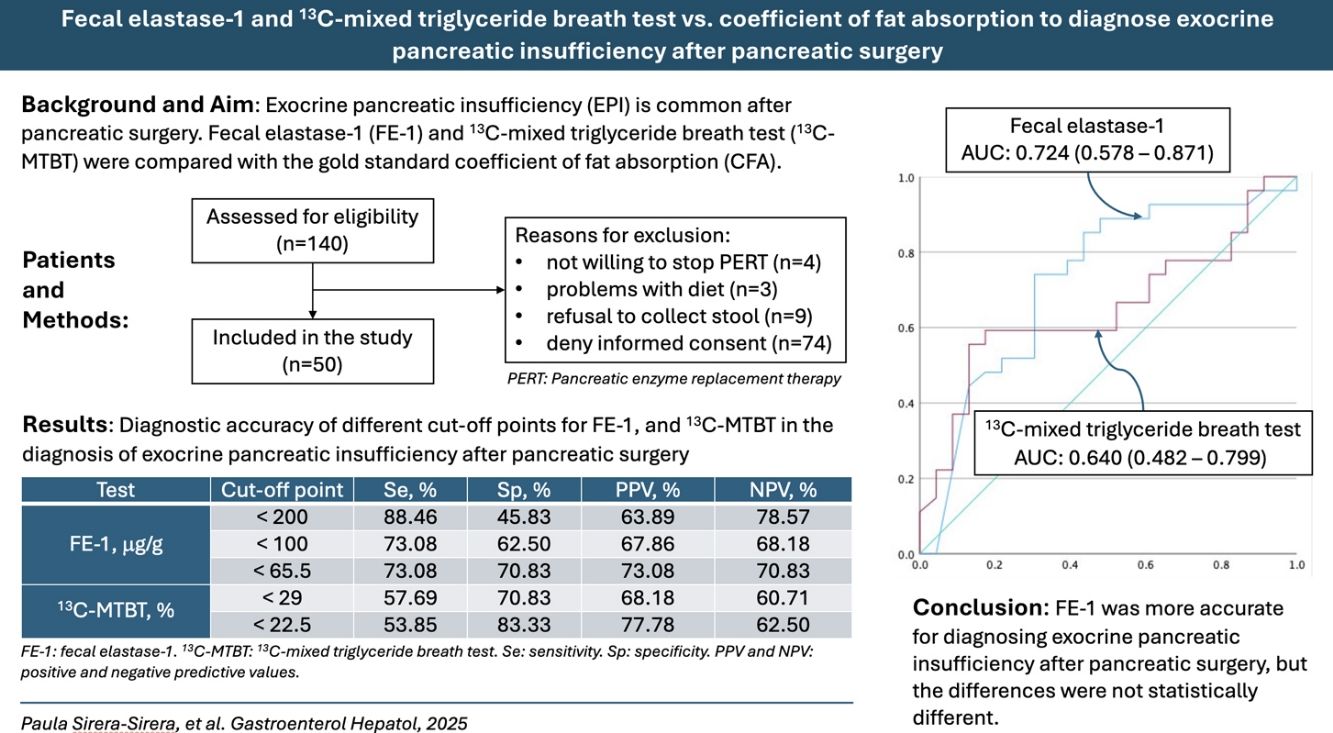

ResultsThe AUC (95% confidence interval) was 0.724 (0.578–0.871) for FE-1 and 0.640 (0.482–0.799) for 13C-MTBT in the diagnosis of EPI. A pairwise comparison of the FE-1 and 13C-MTBT AUCs showed no statistically significant difference (P=.20). The best cut-off point was 65.5μg/g for FE-1 and 22.5% for 13C-MTBT. According to contingency analysis, both the FE-1 threshold of 65.5μg/g (P=.005) and the 13C-MTBT threshold of 22.5% (P=.015) showed statistical significance for diagnosing EPI.

ConclusionFE-1 was more accurate for diagnosing EPI after pancreatic surgery, but the differences were not statistically different.

La insuficiencia pancreática exocrina (EPI) es común después de cirugía pancreática. En pacientes con pancreatitis crónica, nuestros datos favorecen el uso de elastasa fecal-1 (FE-1) sobre la prueba de aliento con 13C-triglicéridos mixtos (13C-MTBT). Sin embargo, es necesario comparar estas dos técnicas en el diagnóstico de EPI después de cirugía pancreática.

Pacientes y métodosFE-1 y 13C-MTBT se compararon con el coeficiente de absorción de grasa (CFA). La detección de EPI se hizo mediante el área bajo la curva (AUC) ROC y los mejores puntos de corte. Las características de los pacientes se compararon en función de la amplitud de resección pancreática.

ResultadosEl AUC (95% intervalo de confianza) fue 0,724 (0,578 – 0,871) para FE-1 y 0,640 (0,482 – 0,799) para 13C-MTBT en el diagnóstico de EPI. No hubo diferencia estadística (P=0,20) al comparar los AUC de FE-1 y 13C-MTBT. El mejor nivel de corte fue 65,5μg/g para FE-1 y 22,5% para 13C-MTBT. Mediante análisis de contingencia, tanto el umbral de 65,5μg/g para FE-1 (P=0,005) como el umbral de 22,5% para 13C-MTBT (P=0,015) mostraron diferencias significativas en el diagnóstico de EPI.

ConclusiónFE-1 fue más precisa que 13C-MTBT en el diagnóstico de EPI después de cirugía pancreática, pero estas diferencias no fueron estadísticamente significativas.

Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI) is a frequent complication of pancreatic diseases. Steatorrhea, defined as more than 7g of fat per day in the stool, appears when the secretion of pancreatic enzymes drops below 10%.1 EPI is common after pancreatic surgery (25–90%),2 resulting from the interplay of several factors. Heterogeneity of underlying pancreatic disease, the extent of surgical resection, postoperative anatomical changes, alteration of neurohormonal mechanisms regulating pancreatic secretion, and modification of gastric emptying may contribute.3

Fecal fat excretion and particularly the coefficient of fat absorption (CFA) are currently the gold standard for diagnosing EPI, but they are difficult to perform and uncomfortable for the patient. In a previous comparative study in patients with chronic pancreatitis, our results supported using fecal elastase-1 (FE-1) over 13C-mixed triglyceride breath test (13C-MTBT) to diagnose EPI.4 Both tests offered similar diagnostic performance, but FE-1 is more cost-effective, requires less time and resources, and is less burdensome for the patient. How the performance of these two tests compares in diagnosing EPI after pancreatic surgery is poorly established.3

Some studies have attempted to validate the performance of these tests in patients after pancreatic surgery. An early study concluded that the performance of FE-1, at 200μg/g stool as a cut-off point, was poor after partial pancreatic resection in cancer patients.5 Shortly thereafter, another study concluded that FE-1 was not useful for detecting steatorrhea after pancreato-duodenectomy for various underlying pancreatic diseases. This study found steatorrhea even in the presence of a mild decrease in FE-1.6 A third study observed a correlation between 13C-MTBT and FE-1 in patients who underwent pancreatic surgery but used clinical steatorrhea as the gold standard instead of quantifying stool fat.7 Studies validating these tests using an adequate gold standard in patients after pancreatic surgery are still needed.8

In the present study, we sought to determine the diagnostic accuracy of FE-1 and 13C-MTBT to identify EPI, using CFA as the gold standard, in a cohort of patients who underwent pancreatic resection. In addition, we assessed their nutritional status.

Patients and methodsStudy designThis was a prospective, observational, descriptive, cross-sectional study of patients who underwent pancreatic surgery between February 2016 and September 2023 at Hospital Dr. Balmis and Hospital Cruces, two public centers in Spain. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Hospital Dr. Balmis (PI 2016-08). Informed consent for participating in this study was obtained from all patients. Planning and analysis were carried out according to the STROBE guidelines.9

Patients and surgical proceduresAdult patients who underwent pancreatic surgery during the study period were included after informed consent was obtained. Patients who underwent ileal resection were excluded from the study. In addition, we excluded patients with severe lung disease requiring oxygen, short bowel syndrome, celiac disease, Crohn's disease, chronic diarrhea of non-pancreatic origin, advanced liver cirrhosis (Child C), biliary obstruction and diabetic gastroparesis. The methodology of the three exocrine pancreatic function tests was explained to the patients in detail, including pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy (PERT) cessation prior to the tests, the need to follow a specific diet for several days, and stool collection according to certain requirements. FE-1 measurement can be performed even if the patient takes PERT medication.2 Patients were analyzed as a whole, and subgroup analysis was performed according to the extent of pancreatic resection: (1) major (i.e., pancreato-duodenectomy); (2) intermediate (i.e., distal pancreatic resection); and (3) minor (i.e., insulinoma enucleation).

Exocrine pancreatic function testsCoefficient of fat absorptionPatients taking PERT were required to discontinue this treatment at least seven days before starting the diet. The dietician provided the patients with a daily diet containing 100g of fat. Patients had to follow the diet for five days and collect stool from the last three days. Daily fecal fat excretion was measured in homogenized stool samples using near-infrared reflectance analysis. The CFA (%) was calculated as follows: 100×[(mean daily fat intake−mean daily stool fat)/mean daily fat intake].10 EPI was defined as CFA less than 93%.

Fecal elastase-1Methodological validation was carried out beforehand. The weighing method was compared with a new extraction protocol. Briefly, 32 samples of liquid or semi-liquid stool, frozen at −20°C, were selected and submitted for fecal elastase testing. All samples were processed in duplicate for both methods. For the weighing method, the manufacturer's recommendations were followed. For the new extraction protocol, 15μL of liquid sample was added to 6mL of buffer contained in the extraction device. The mixture was vortexed for 30min and processed on the Liaison XL® autoanalyzer. Comparability was assessed by Passing–Bablok correlation and linear regression. The coefficients of variation were 9.47% for the weighing method and 14.52% for the new extraction method (both less than 15%), which are acceptable values for a heterogeneous sample such as feces. The test was performed on a random sample of a semi-solid or solid stool specimen. In the liquid stool samples, 16μL were analyzed. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (ScheBo®, BioTech AG, Giessen, Germany) was used. An FE-1 value<100μg/g feces is considered severe EPI, while a level of 100–200μg/g is usually considered mild EPI.10

13C-mixed triglyceride breath testThe 13C-MTBT measures lipase activity in the intestinal lumen by detecting the labeled carbon released by the digestion and absorption of fat.11,12 After an overnight fast, 13C-triglycerides (250mg) were given orally mixed with a standard solid test meal containing butter spread on two slices of toasted white bread (16g fat, 40g bread, 200mL water).8 Breath samples were collected before ingestion of the test meal and at 30-minute intervals for 6h and stored in tubes. The 13CO2/12CO2 ratio was measured with mass spectrophotometry in each breath sample (Pancreo-kit®, Isomed Pharma, Madrid, Spain). The test result was the cumulative recovery rate of 13CO2 over the 6h. A cut-off value of 29% is usually used.10,13

Nutritional status assessmentWe used CONUT, a simple tool based on readily available laboratory data (serum albumin, total cholesterol, and lymphocyte count) to assess nutritional status, which correlates well with a more comprehensive nutritional assessment test.14 It has been used to objectively quantify nutritional status in patients with various benign and malignant conditions and to predict the risk of postoperative pancreatic fistula after pancreatoduodenectomy.15

AnalysisDescriptive statistics were used for demographic and baseline characteristics of patients. Quantitative variables are reported as median and interquartile range (IQR), categorical variables as absolute and relative frequencies. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Differences between groups of patients were compared using the Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test for categorical data, the Student's t-test for quantitative parametric data, and the Mann–Whitney U test for quantitative non-parametric data. For multiple comparisons of nonparametric data, the Kruskal–Wallis's test was used. Diagnostic performance for FE-1 and 13C-MTBT was calculated using CFA as the gold standard. Goodness-of-fit was assessed by the Hosmer–Lemeshow test,16 and discriminatory power by the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC). Pairwise comparison of AUC was performed according to Hanley and McNeil.17 Optimal cut-off values were selected based on the Youden method. The dependence relationship between tests was further examined by contingency analysis. Sensitivity (Se), specificity (Sp), positive (PPV) and negative (NPV) predictive value for FE-1 and 13C-MTBT, was calculated. P values of less than .05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using RStudio, version 1.2.5001 (Integrated Development for R. RStudio, Inc., Boston, MA, USA).

ResultsA total of 140 patients who underwent pancreatic surgery during the study period were contacted. Of these, 90 patients were excluded. Reasons for exclusion were not willing to stop PERT (n=4), problems with diet (n=3), refusal to collect stool (n=9), and denying informed consent (n=74). Finally, 50 patients were included in the study.

Demographic and clinical characteristics according to the coefficient of fat absorptionDemographic and clinical characteristics according to CFA are displayed in Table 1. EPI was detected in 26 (52%) patients. Age, sex, body mass index (BMI), diagnosis, type of surgical procedure, and extent of pancreatic resection were similar in both groups. Patients with EPI presented lower FE-1 in stool (P=.006) and higher fecal fat excretion (P<.001). As expected, 13C-MTBT was lower in patients with EPI, but the difference was not statistically significant. Of note, plasma vitamin D concentration was lower in patients with EPI (P=.004). There were no differences in the other nutritional parameters examined.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients ranked by the malabsorption-defining coefficient of fat absorption.

| Coefficient of fat absorption≥93%n=24 | Coefficient of fat absorption<93%n=26 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 63.5 (54.0–69.2) | 62.0 (56.0–68.8) | .98 |

| Sex, n (%) | .74 | ||

| Male | 15 (62.5) | 14 (53.8) | |

| Female | 9 (37.5) | 12 (46.2) | |

| BMI, kg/m2, median (IQR) | 25.0 (22.4–27.5) | 23.6 (22.2–25.4) | .30 |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | .20 | ||

| Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma | 5 (20.8) | 10 (38.5) | |

| Periampullary cancer | 0 | 2 (7.7) | |

| Neuroendocrine tumor | 4 (16.7) | 6 (23.1) | |

| Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasia | 3 (12.5) | 3 (11.5) | |

| Mucinous cystic adenoma | 0 | 1 (3.8) | |

| Serous cystic adenoma | 1 (4.2) | 0 | |

| Chronic pancreatitis | 8 (33.3) | 2 (7.7) | |

| Acute pancreatitis | 3 (12.5) | 2 (7.7) | |

| Surgical procedure, n (%) | .25 | ||

| Pancreatoduodenectomy | 12 (50.0) | 17 (65.4) | |

| Distal pancreatectomy | 5 (20.8) | 5 (19.2) | |

| Necrosectomy | 3 (12.5) | 0 | |

| Lateral pancreatojejunostomy | 2 (8.3) | 2 (7.7) | |

| Cysto-gastrostomy | 0 | 2 (7.7) | |

| Enucleation | 1 (4.2) | 0 | |

| Other | 1 (4.2) | 0 | |

| Extent of pancreatic resection, n (%) | .45 | ||

| Major | 12 (50.0) | 17 (65.4) | |

| Intermediate | 5 (20.8) | 5 (19.2) | |

| Minor | 7 (29.2) | 4 (15.4) | |

| Pancreatic function test, median (IQR) | |||

| Fecal elastase-1, μg/g | 169.0 (36.5–343.0) | 15.5 (10.0–103.2) | .006 |

| Mean fecal fat excretion, g | 4.0 (2.8–5.6) | 21.5 (13.0–30.4) | <.001 |

| 13C-mixed triglyceride breath test, % | 34.5 (26.0–40.0) | 21.5 (3.2–38.5) | .09 |

| Laboratory data, median (IQR) | |||

| Cholesterol, mg/dL | 160 (131–179) | 165 (128–184) | .95 |

| Albumin, mg/dL | 4.2 (4.0–4.4) | 4.0 (3.7–4.3) | .19 |

| Pre-albumin, mg/dL | 22.5 (19.9–27.2) | 20.0 (17.5–25.0) | .16 |

| Vitamin D, ng/mL | 23.6 (19.6–32.8) | 17.3 (10.2–21.6) | .004 |

| Vitamin A, ng/mL | 0.5 (0.4–0.6) | 0.4 (0.3–0.5) | .26 |

| Vitamin E, ng/mL | 12.6 (10.5–14.9) | 11.1 (9.6–13.7) | .29 |

| Vitamin B12, pg/mL | 441 (315–601) | 358 (296–445) | .08 |

| Folic acid, ng/mL | 9.4 (7.5–13.3) | 9.0 (7.2–11.7) | .73 |

| Lymphocytes, n, ×103 | 2.0 (1.8–2.5) | 1.9 (1.5–2.5) | .39 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 13.2 (12.3–14.2) | 13.5 (12.6–14.4) | .97 |

| CONUT score, n (%) | .76 | ||

| 0 | 5 (20.8) | 6 (23.1) | |

| 1 | 12 (50.0) | 10 (38.5) | |

| 2 | 5 (20.8) | 4 (15.4) | |

| 3 | 1 (4.2) | 2 (7.7) | |

| 4 | 1 (4.2) | 3 (11.5) | |

| 5 | 0 | 1 (3.8) | |

Values of P<.05 are in bold.

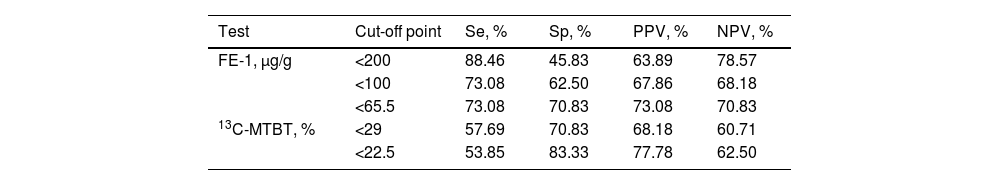

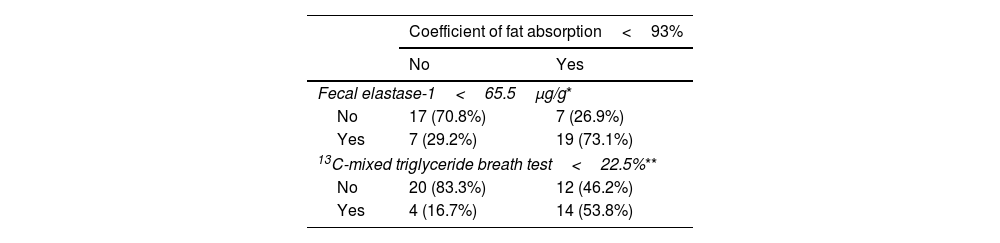

The AUC (95% CI) was 0.724 (0.578–0.871) for FE-1, and 0.640 (0.482–0.799) for 13C-MTBT in the diagnosis of EPI (Fig. 1). Pairwise comparison of the FE-1 and 13C-MTBT AUCs according to the Hanley and McNeil method showed no statistically significant difference (P=.20). Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values for the different cut-off points of FE-1 and 13C-MTBT are shown in Table 2. The best cut-off point was 65.5μg/g for FE-1, and 22.5% for 13C-MTBT. According to contingency analysis, both FE-1 threshold of 65.5μg/g (P=.005) and 13C-MTBT threshold of 22.5% (P=.015) showed statistical significance for the diagnosis of EPI (Table 3).

Area under the receiving operating characteristics curve (AUC) of fecal elastase-1 (left panel) and 13C-mixed triglyceride breath test (right panel) in the diagnosis of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, defined according to a coefficient of fat absorption<93%, in patients after pancreatic surgery.

Diagnostic accuracy of different cut-off points for fecal elastase-1, and 13C-mixed triglyceride breath test in the diagnosis of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency after pancreatic surgery.

| Test | Cut-off point | Se, % | Sp, % | PPV, % | NPV, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FE-1, μg/g | <200 | 88.46 | 45.83 | 63.89 | 78.57 |

| <100 | 73.08 | 62.50 | 67.86 | 68.18 | |

| <65.5 | 73.08 | 70.83 | 73.08 | 70.83 | |

| 13C-MTBT, % | <29 | 57.69 | 70.83 | 68.18 | 60.71 |

| <22.5 | 53.85 | 83.33 | 77.78 | 62.50 |

FE-1: fecal elastase-1. 13C-MTBT: 13C-mixed triglyceride breath test. Se: sensitivity. Sp: specificity. PPV and NPV: positive and negative predictive values.

Contingency table including patients diagnosed with exocrine pancreatic insufficiency according to coefficient of fat absorption<93%, fecal elastase-1 (<65.5μg/g, and 13C-mixed triglyceride breath test<22.5%.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients ranked by the FE-1 best cut-off point are shown in Table 4. More patients undergoing pancreatoduodenectomy (P=.001) and thus major pancreatic resection (P<.001) were found among those with FE-1<65.5μg/g. In addition, patients with FE-1<65.5μg/g had more fecal fat (P=.002) and lower CFA (P=.001), and they also showed lower 13C-MTBT values (P<.001). Notably, serum vitamin E levels were lower in patients with FE-1<65.5μg/g (P=.009).

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients ranked by the fecal elastase-1 best cut-off point.

| Fecal elastase-1≥65.5μg/gn=24 | Fecal elastase-1<65.5μg/gn=26 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 63.5 (54.0–67.8) | 62.0 (55.2–69.0) | .98 |

| Sex, n (%) | .81 | ||

| Male | 13 (54.2) | 16 (61.5) | |

| Female | 11 (45.8) | 10 (38.5) | |

| BMI, kg/m2, median (IQR) | 25.6 (22.8–27.8) | 23.4 (22.2–25.2) | .08 |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | .33 | ||

| Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma | 4 (16.7) | 11 (42.3) | |

| Periampullary cancer | 1 (4.2) | 1 (3.8) | |

| Neuroendocrine tumor | 7 (29.2) | 3 (11.5) | |

| Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasia | 2 (8.3) | 4 (15.4) | |

| Mucinous cystic adenoma | 0 | 1 (3.8) | |

| Serous cystic adenoma | 1 (4.2) | 0 | |

| Chronic pancreatitis | 6 (25.0) | 4 (15.4) | |

| Acute pancreatitis | 3 (12.5) | 2 (7.7) | |

| Surgical procedure, n (%) | .001 | ||

| Pancreatoduodenectomy | 7 (29.2) | 22 (84.6) | |

| Distal pancreatectomy | 9 (37.5) | 1 (3.8) | |

| Necrosectomy | 3 (12.5) | 0 | |

| Lateral pancreatojejunostomy | 3 (12.5) | 1 (3.8) | |

| Cysto-gastrostomy | 0 | 2 (7.7) | |

| Enucleation | 1 (4.2) | 0 | |

| Other | 1 (4.2) | 0 | |

| Extent of pancreatic resection, n (%) | <.001 | ||

| Major | 7 (29.2) | 22 (84.6) | |

| Intermediate | 9 (37.5) | 1 (3.8) | |

| Minor | 8 (33.3) | 3 (11.5) | |

| Pancreatic function test, median (IQR) | |||

| Fecal elastase-1, μg/g | 264.5 (143.0–402.0) | 10.0 (10.0–29.0) | <.001 |

| Mean fecal fat excretion, g | 6.0 (3.0–11.6) | 18.3 (6.3–26.7) | .002 |

| Coefficient of fat absorption, % | 94.0 (88.0–97.0) | 82.0 (73.5–93.8) | .001 |

| 13C-mixed triglyceride breath test, % | 40.0 (32.8–42.0) | 10.0 (3.0–34.0) | <.001 |

| Laboratory data, median (IQR) | |||

| Cholesterol, mg/dL | 171 (130–188) | 159 (130–175) | .28 |

| Albumin, mg/dL | 4.2 (3.8–4.2) | 4.2 (3.9–4.4) | .68 |

| Pre-albumin, mg/dL | 22.5 (20.0–26.2) | 20.0 (16.2–25.0) | .07 |

| Vitamin D, ng/mL | 22.4 (17.8–31.4) | 18.4 (10.4–23.0) | .09 |

| Vitamin A, ng/mL | 0.5 (0.4–0.6) | 0.4 (0.3–0.5) | .07 |

| Vitamin E, ng/mL | 13.6 (11.8–15.0) | 10.6 (9.1–13.0) | .009 |

| Vitamin B12, pg/mL | 440 (315–601) | 358 (296–467) | .11 |

| Folic acid, ng/mL | 8.7 (7.5–11.1) | 9.4 (6.2–14.6) | .95 |

| Lymphocytes, n, ×103 | 2.0 (1.6–2.3) | 2.1 (1.7–2.5) | .53 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 13.2 (12.9–14.2) | 13.5 (12.0–14.4) | .59 |

| CONUT score, n (%) | .28 | ||

| 0 | 8 (33.3) | 3 (11.5) | |

| 1 | 8 (33.3) | 14 (53.8) | |

| 2 | 5 (20.8) | 4 (15.4) | |

| 3 | 1 (4.2) | 2 (7.7) | |

| 4 | 1 (4.2) | 3 (11.5) | |

| 5 | 1 (4.2) | 0 | |

Values of P<.05 are in bold.

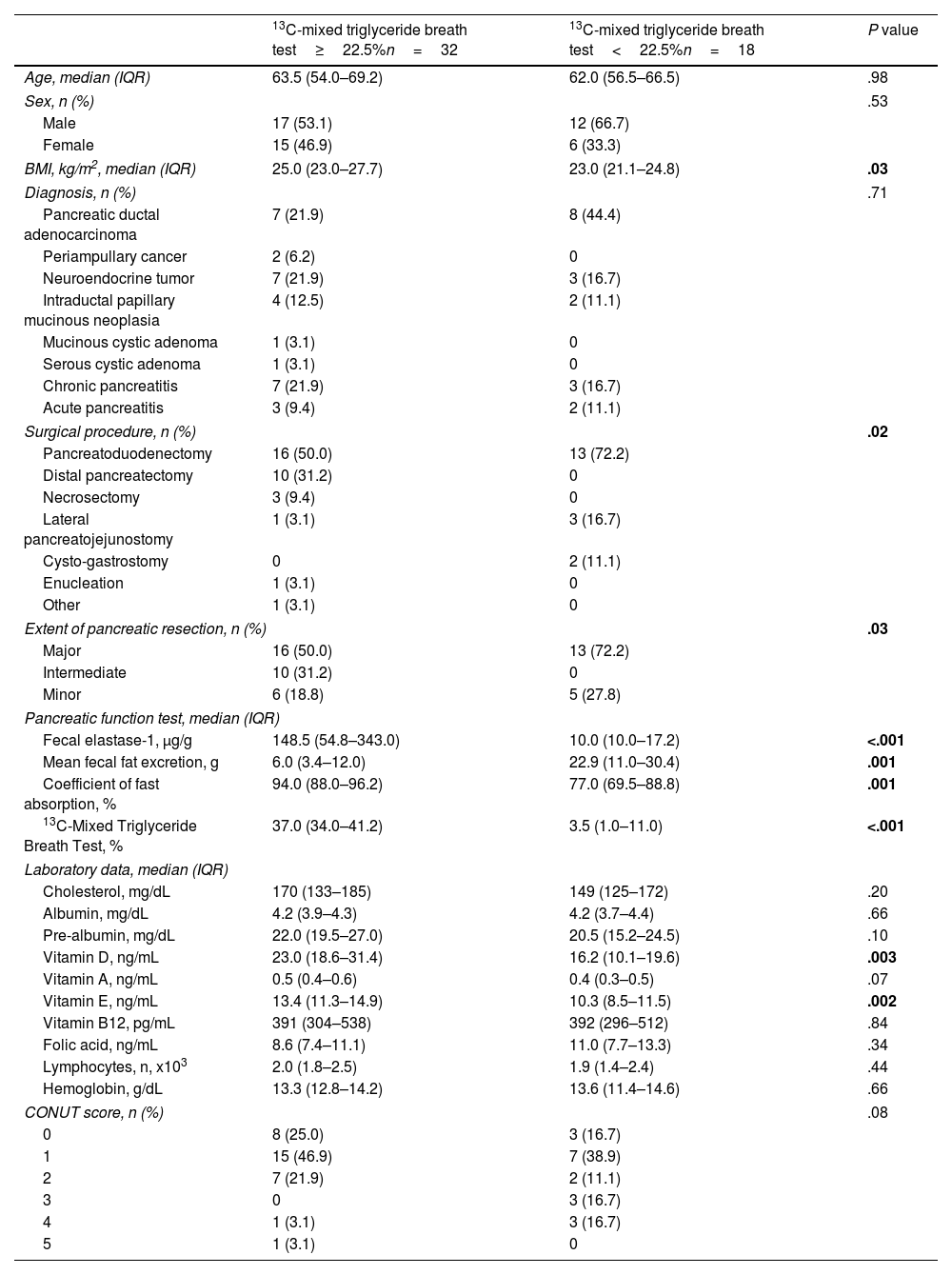

Characteristics of patients ranked by 13C-MTBT best cut-off point are depicted in Table 5. Categorization using the best cut-off point for 13C-MTBT (22.5%) for detection of EPI placed more patients above (n=32) than below (n=18) the cut-off point. BMI was lower in patients with 13C-MTBT<22.5% (P=.03). More patients undergoing major pancreatic resection (P=.03) were found among those with 13C-MTBT<22.5%. As expected, FE-1 was lower (P<.001) and fecal fat excretion was higher (P=.001) in patients with 13C-MTBT<22.5%. Likewise, vitamin D (P=.003) and vitamin E (P=.002) levels were lower in patients with 13C-MTBT<22.5%.

Characteristics of patients ranked by 13C-mixed triglyceride breath test best cut-off point.

| 13C-mixed triglyceride breath test≥22.5%n=32 | 13C-mixed triglyceride breath test<22.5%n=18 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 63.5 (54.0–69.2) | 62.0 (56.5–66.5) | .98 |

| Sex, n (%) | .53 | ||

| Male | 17 (53.1) | 12 (66.7) | |

| Female | 15 (46.9) | 6 (33.3) | |

| BMI, kg/m2, median (IQR) | 25.0 (23.0–27.7) | 23.0 (21.1–24.8) | .03 |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | .71 | ||

| Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma | 7 (21.9) | 8 (44.4) | |

| Periampullary cancer | 2 (6.2) | 0 | |

| Neuroendocrine tumor | 7 (21.9) | 3 (16.7) | |

| Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasia | 4 (12.5) | 2 (11.1) | |

| Mucinous cystic adenoma | 1 (3.1) | 0 | |

| Serous cystic adenoma | 1 (3.1) | 0 | |

| Chronic pancreatitis | 7 (21.9) | 3 (16.7) | |

| Acute pancreatitis | 3 (9.4) | 2 (11.1) | |

| Surgical procedure, n (%) | .02 | ||

| Pancreatoduodenectomy | 16 (50.0) | 13 (72.2) | |

| Distal pancreatectomy | 10 (31.2) | 0 | |

| Necrosectomy | 3 (9.4) | 0 | |

| Lateral pancreatojejunostomy | 1 (3.1) | 3 (16.7) | |

| Cysto-gastrostomy | 0 | 2 (11.1) | |

| Enucleation | 1 (3.1) | 0 | |

| Other | 1 (3.1) | 0 | |

| Extent of pancreatic resection, n (%) | .03 | ||

| Major | 16 (50.0) | 13 (72.2) | |

| Intermediate | 10 (31.2) | 0 | |

| Minor | 6 (18.8) | 5 (27.8) | |

| Pancreatic function test, median (IQR) | |||

| Fecal elastase-1, μg/g | 148.5 (54.8–343.0) | 10.0 (10.0–17.2) | <.001 |

| Mean fecal fat excretion, g | 6.0 (3.4–12.0) | 22.9 (11.0–30.4) | .001 |

| Coefficient of fast absorption, % | 94.0 (88.0–96.2) | 77.0 (69.5–88.8) | .001 |

| 13C-Mixed Triglyceride Breath Test, % | 37.0 (34.0–41.2) | 3.5 (1.0–11.0) | <.001 |

| Laboratory data, median (IQR) | |||

| Cholesterol, mg/dL | 170 (133–185) | 149 (125–172) | .20 |

| Albumin, mg/dL | 4.2 (3.9–4.3) | 4.2 (3.7–4.4) | .66 |

| Pre-albumin, mg/dL | 22.0 (19.5–27.0) | 20.5 (15.2–24.5) | .10 |

| Vitamin D, ng/mL | 23.0 (18.6–31.4) | 16.2 (10.1–19.6) | .003 |

| Vitamin A, ng/mL | 0.5 (0.4–0.6) | 0.4 (0.3–0.5) | .07 |

| Vitamin E, ng/mL | 13.4 (11.3–14.9) | 10.3 (8.5–11.5) | .002 |

| Vitamin B12, pg/mL | 391 (304–538) | 392 (296–512) | .84 |

| Folic acid, ng/mL | 8.6 (7.4–11.1) | 11.0 (7.7–13.3) | .34 |

| Lymphocytes, n, x103 | 2.0 (1.8–2.5) | 1.9 (1.4–2.4) | .44 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 13.3 (12.8–14.2) | 13.6 (11.4–14.6) | .66 |

| CONUT score, n (%) | .08 | ||

| 0 | 8 (25.0) | 3 (16.7) | |

| 1 | 15 (46.9) | 7 (38.9) | |

| 2 | 7 (21.9) | 2 (11.1) | |

| 3 | 0 | 3 (16.7) | |

| 4 | 1 (3.1) | 3 (16.7) | |

| 5 | 1 (3.1) | 0 | |

Values of P<.05 are in bold.

The distribution of diagnoses according to the extent of pancreatic resection was unequal (P=.003) (Table 6). As expected, patients with major pancreatic resection had a lower concentration of FE-1 in stool (P<.001) and a lower proportion of expired 13C (P=.01). According to CFA, the ratio of patients with EPI was similar regardless of the extent of pancreatic resection. However, the ratio of patients with EPI was unequal according to FE-1 (P<.001) or 13C-MTBT (P=.03) best cut-off points, respectively.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients ranked by extent of pancreatic resection.

| Majorn=29 | Intermediaten=10 | Minorn=11 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 62.0 (55.0–68.0) | 67.5 (52.0–71.8) | 61.0 (55.5–67.0) | .78 |

| Sex,n(%) | .19 | |||

| Male | 15 (51.7) | 5 (50.0) | 9 (81.8) | |

| Female | 14 (48.3) | 5 (50.0) | 2 (18.2) | |

| BMI, kg/m2, median (IQR) | 24.4 (22.8–26.4) | 24.5 (22.8–26.9) | 22.1 (21.2–27.9) | .68 |

| Diagnosis,n(%) | .003 | |||

| Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma | 11 (37.9) | 3 (30.0) | 1 (9.1) | |

| Periampullary cancer | 2 (6.9) | 0 | 0 | |

| Neuroendocrine tumor | 4 (13.8) | 5 (50.0) | 1 (9.1) | |

| Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasia | 5 (17.2) | 1 (10.0) | 0 | |

| Mucinous cystic adenoma | 1 (3.4) | 0 | 0 | |

| Serous cystic adenoma | 1 (3.4) | 0 | 0 | |

| Chronic pancreatitis | 5 (17.2) | 1 (10.0) | 4 (36.4) | |

| Acute pancreatitis | 0 | 0 | 5 (45.5) | |

| Pancreatic function test, median (IQR) | ||||

| Fecal elastase-1, μg/g stool | 18 (10–62) | 306 (153.2–480) | 283 (39.5–344) | <.001 |

| Mean fecal fat excretion, g | 12.7 (4.9–21.6) | 8.9 (5.0–11.8) | 6.5 (3.0–25.5) | .60 |

| Coefficient of fat absorption, % | 87.0 (78.0–95.0) | 91.0 (88.0–94.8) | 93.0 (74.5–97.0) | .73 |

| 13C-mixed triglyceride breath test, % | 23.0 (3.0–36.0) | 40.5 (36.2–41.0) | 31.0 (17.0–39.0) | .01 |

| Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency,n(%) | ||||

| Coefficient of fat absorption | .45 | |||

| ≥93% | 12 (41.4) | 5 (50.0) | 7 (63.6) | |

| <93% | 17 (58.6) | 5 (50.0) | 4 (36.4) | |

| Fecal elastase 1 | <.001 | |||

| ≥65.5μg/g | 7 (24.1) | 9 (90.0) | 8 (72.7) | |

| <65.5μg/g | 22 (75.9) | 1 (10.0) | 3 (27.3) | |

| 13C-mixed triglyceride breath test | .03 | |||

| ≥22.5% | 16 (55.2) | 10 (100.0) | 6 (54.5) | |

| <22.5% | 13 (44.8) | 0 | 5 (45.5) | |

Values of P<.05 are in bold.

In summary, our study compared two pancreatic function tests with the coefficient of fat absorption as the gold standard in patients after three degrees of pancreatic resection owing to various underlying pancreatic diseases. We first calculated the area under the ROC curve and estimated the best cut-off point for each test to assess the presence of EPI after surgery. Next, we examined the characteristics of patients ranked according to the best cut-off point for each test, and according to the extent of pancreatic resection as well.

Studies examining EPI after pancreatic resection surgery by quantifying FE-1 in stool usually rely on pre-established cut-off points for this enzyme in previous literature without testing it against the hard-to-measure actual fat excretion in their patients.18 Based on a cut-off point of 200μg/g stool, Stern et al.19 found EPI in 86% of patients after pancreatic head resection for underlying malignant or benign disease and in 33% of patients after distal pancreatectomy. In our study, comparing FE-1 values with actual fat excretion, 75.9% of patients had FE-1 values below the best cut-off point (65.5μg/g stool) after major pancreatic resection, 10% after intermediate resection, and 27.3% after minor pancreatic resection. This suggests that the lack of a gold standard may hinder the interpretation of results leading to a diagnosis of EPI.

Looking specifically at patients after pancreatoduodenectomy for cancer, Kumar et al.20 found 33% of patients with FE-1 between 200μg/g and 100μg/g, while this percentage rose to 67% if the FE-1 threshold was lowered to <100μg/g. The median FE-1 was 74.6μg/g in Kumar's study, while it decreased to 18 (10–62) μg/g in our patients after pancreatoduodenectomy. In fact, the article by Kumar et al.20 reviewed several studies in which the mean or median FE-1 values after pancreatoduodenectomy ranged from 12 to 104μg/g. It seems clear that there is a large variability, possibly due partly to study design, which makes it difficult to define the FE-1 level consistent with EPI. These data emphasize the need to correlate pancreatic function test findings with actual fat loss in patients after pancreatic surgery.

Regarding minor pancreatic resection, Nøjgaard et al.21 found FE-1 values<100μg/g and <200 in 25% and 59% of patients, respectively, after an episode of complicated walled-off pancreatic necrosis. However, only 24% of these patients required PERT, a figure close to the 27.3% of our patients with minor pancreatic resection and EF-1 below the best cut-off point. Care should be exercised in the diagnosis of EPI after pancreatic surgery as it would lead to the initiation of PERT.1

According to several authors, a 13C-MTBT<23% is diagnostic of EPI and is, therefore, an indication for PERT. Notably, our study found 22.5% as the best cut-off point, a figure almost identical to the above. Using this <23% threshold, Hartman et al.22 diagnosed EPI in 68% of patients after pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Similarly, in our study, 44.8% of patients undergoing major pancreatic resection had a 13C-MTBT<22.5%. On the other hand, only a minority of patients undergoing distal pancreatectomy in the study by Hartman et al.22 had 13C-MTBT<23%. Similarly, none of our patients undergoing intermediate pancreatic resection had 13C-MTBT<22.5%. However, 45.5% of our patients undergoing minor pancreatic resection had 13C-MTBT<22.5%, although it should be noted that in our study there were patients with chronic pancreatitis among those undergoing minor pancreatic resection. Therefore, in addition to the extent of resection, factors such as underlying pancreatic disease may influence fat malabsorption after pancreatic surgery.

Vitamin D deficiency may be present in patients with fat malabsorption.23 Our study found a significantly decrease of vitamin D level in patients with fat malabsorption after pancreatic resection. Of note, this depletion was detected by both CFA and 13C-MTBT in our study. In addition, early studies reported vitamin E deficiency in patients with EPI.24 In our study, both FE-1 and 13C-MTBT detected depletion of vit E. These data alert to the need for supplementation in patients at risk of vitamin deficiency.

There are limitations to our study. We have not provided data on signs and/or symptoms suggestive of EPI/malabsorption – such as diarrhea, abdominal distension, low weight or sarcopenia – as these variables were not included in the ethics committee-approved study protocol. Our cohort's diversity of diagnoses and procedures hampers the establishment of precise cut-off points applicable to specific patients. However, the usual clinical scenario is often subject to stress due to several factors acting simultaneously. Our study did not assess the consistency of the remaining pancreas, of great importance in the reserve of exocrine pancreatic function. Neither the diameter of the Wirsung duct nor the histological characteristics of the remnant pancreas were examined. Adjuvant and/or neoadjuvant treatments administered to patients with malignancies may also have influenced the results. As well as the length of time between surgery and the performance of pancreatic function tests. Unfortunately, no further conclusions could be drawn due to variability in the time interval between surgery and the performance of pancreatic function tests. Certainly, other variables may have influenced our results. In any case, our study highlights the need for further prospective studies.

ConclusionIn conclusion, FE-1 was more accurate for diagnosing EPI after pancreatic surgery, but the differences were not statistically different.

Author contributionPaula Sirera-Sirera: Conception and design, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting the article, Revising the article. Núria Lluís: Analysis and interpretation of data, Revising the article. Fèlix Lluís: Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting the article, Revising the article. Pedro Zapater: Analysis and interpretation of data, Revising the article. Pablo López-Guillén: Acquisition of data, Revising the article. José M. Ramia-Ángel: Acquisition of data, Revising the article. Rahma Amrani: Acquisition of data, Revising the article. Trinidad Castillo-García: Acquisition of data, Revising the article. José Andreu-Viseras: Acquisition of data, Revising the article. Karina Cárdenas-Jaén: Conception and design, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Revising the article. Lucía Guilabert: Acquisition of data, Revising the article. Sara Pérez-Brotons: Acquisition of data, Revising the article. Emma Martínez-Moneo: Acquisition of data, Revising the article. Nerea Gendive-Martin: Acquisition of data, Revising the article. Iván González Hermoso: Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Revising the article. Enrique de-Madaria: Conception and design, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting the article, Revising the article. María José Ferri: Conception and design, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting the article, Revising the article.

Ethical considerationsThe work was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Hospital Dr. Balmis (PI 2016-08). Informed consent for participating in this study was obtained from all patients.

Source of fundingViatris Inc. funded this study. Viatris was not involved in its design, execution, or manuscript drafting.

Conflict of interestEnrique de-Madaria has received grants from Viatris Inc. and Abbott, and has participated in symposia funded by Janssen, Abbie, Viatris Inc. and Abbott.

We are grateful to Viatris Inc. for funding the study and particularly to Maria Luisa Orera, Global Medical Lead Gastroenterology, for her support.