There is uncertainty regarding Wilson's disease (WD) management.

ObjectivesTo assess, in a multicenter Spanish retrospective cohort study, whether the approach to WD is homogeneous among centers.

MethodsData on WD patients followed at 32 Spanish hospitals were collected.

Results153 cases, 58% men, 20.6 years at diagnosis, 69.1% hepatic presentation, were followed for 15.5 years. Discordant results in non-invasive laboratory parameters were present in 39.8%. Intrahepatic copper concentration was pathologic in 82.4%. Genetic testing was only done in 56.6% with positive results in 83.9%. A definite WD diagnosis (Leipzig score ≥4) was retrospectively confirmed in 92.5% of cases. Chelating agents were standard initial therapy (75.2%) with frequent modifications (57%), particularly to maintenance zinc. Enzyme normalization was not achieved by one third, most commonly in the setting of poor compliance, lack of genetic mutations and/or presence of cardiometabolic risk factors. Although not statistically significant, there were trends for sex differences in number of diagnosed cases, age at diagnosis and biochemical response.

ConclusionsSignificant heterogeneity in diagnosis and management of WD patients emerges from this multicenter study that includes both small and large reference centers. The incorporation of genetic testing will likely improve diagnosis. Sex differences need to be further explored.

Existe incertidumbre con respecto al manejo de la enfermedad de Wilson (EW).

ObjetivosEvaluar, en un estudio de cohorte retrospectivo español multicéntrico, si el abordaje de la EW es homogéneo entre los centros.

MétodosSe recogieron datos sobre pacientes con EW seguidos en 32 hospitales españoles.

ResultadosUn total de 153 casos, 58% hombres, 20,6 años al diagnóstico, 69,1% presentación hepática, fueron seguidos durante 15,5 años. Se objetivaron resultados discordantes en parámetros de laboratorio no invasivos en el 39,8%. La concentración intrahepática de cobre fue patológica en el 82,4%. Las pruebas genéticas solo se realizaron en el 56,6% con resultados positivos en el 83,9%. Un diagnóstico definitivo de EW (puntuación de Leipzig ≥4) se confirmó retrospectivamente en el 92,5% de los casos. Los agentes quelantes fueron la terapia inicial estándar (75,2%) con modificaciones frecuentes (57%), particularmente hacia zinc de mantenimiento. La normalización enzimática no se logró en un tercio, más comúnmente en el contexto de un cumplimiento deficiente, ausencia de mutaciones genéticas y/o presencia de factores de riesgo cardiometabólicos. Aunque sin alcanzar significación estadística, observamos diferencias entre hombres y mujeres en el número de casos, edad en el momento del diagnóstico y la respuesta bioquímica.

ConclusionesDe este estudio multicéntrico que incluye centros de referencia pequeños y grandes se desprende una heterogeneidad significativa en el diagnóstico y manejo de los pacientes con EW. La incorporación de pruebas genéticas ha mejorado el diagnóstico. Las diferencias de sexo deben explorarse más a fondo en estudios futuros.

Wilson's disease (WD) is a genetic disease caused by a mutation of the ATP7B protein that induces an inability to eliminate copper in the bile, with the consequent retention of copper in the liver, and eventually in the nervous system and other organs.1 Without treatment, liver disease evolves from simple steatosis to cirrhosis, and during this evolution neurological lesions may appear.1,2 Two different types of therapy are available, copper chelators, such as penicillamine and trientine, and zinc salts, which administered orally prevent the absorption of copper from the diet. If the treatment is administered at early stages of the disease, it prevents its progression and allows the life expectancy of treated patients to be like that of the general population of the same age and sex.3,4

While major advances have occurred in recent years, including genetic testing for diagnosis using novel, simpler and less expensive techniques, there are still areas of uncertainty regarding diagnostic tools and therapeutic strategies in patients diagnosed with WD.1,3,5–8 These include for instance a clear understanding of the prevalence and incidence of the disease as well as the distribution of genetic mutations, the establishment of a phenotype–genotype correlation – if present, reliable tools to assess treatment adherence, and better or more oriented therapies. Indeed, based on next-generation sequencing data, the genetic prevalence of Wilson disease may be greater than previous estimates, at about 15.4 per 100,000 (95% CI: 14.4–16.5), or 1 per 6494 which would suggest underestimation of previous estimates.9–12 In fact, the wide range of phenotypic manifestations of WD with overlapping ages of presentation and multisystem involvement makes the underdiagnosis highly possible.13 Furthermore, while there does not appear to be a clear correlation between the type of genetic mutation and the clinical expression of the disease,4,14 the data are inconclusive.6,7 Finally, a potential differential efficacy of the treatments according to the pattern of presentation is also a relevant aspect. Previous studies describe a poorer liver response when treatment is based on zinc15,16 while some experts argue against D-penicillamine therapy in those with neurological presentation.1,7,8

In 2017, within GEMHEP (Spanish Group of Women Hepatologists), we started a multicenter collaboration in Spain to study patients with WD, diagnosed and followed both in large reference hepatology Units as well as in smaller digestive disease units. The main objective was to establish a map of Wilson's disease in our country. The secondary objectives were to: (i) determine the reliability of the different diagnostic tools; (ii) clarify the most used therapeutic strategies in our environment; and (iii) determine the efficacy and tolerability of zinc treatment in patients with a liver presentation pattern.

Material and methodsObservational, retrospective, descriptive study in which clinical and laboratory data on WD patients followed at 32 Spanish hospitals were collected. Clinical data included sex, age at diagnosis, type of presentation (liver, neurological, asymptomatic), presence of cirrhosis based on histological and/or clinical-imaging data, presence of Keyser-Fleischer (KF) ring, tools to reach the diagnosis (laboratory, liver biopsy, genetic studies) as well as first and second-line therapies (including penicillamine, trientine, zinc, tetrathiomolibdate ammonium or others). Pathological laboratory results included a serum ceruloplasmin <20mg/dl, 24-h urine copper (>100mcg/24h or >1.6μmol/24h in adults and >40mcg/24h or 0.64μmol/24h in children), and a liver concentration of copper >250mcg or 4μmol. Reasons to switch therapies included adverse events, lack of efficacy (defined by lack of complete normalization of liver enzymes and/or lack of clinical improvement) or modification in the setting of maintenance therapy. Laboratory data included serum transaminases, creatinine, ceruloplasmin, 24-h cupruria and serum copper recorded at different time points. Efficacy to treatment was assessed through normalization of liver enzymes in case of liver involvement (based on normality range in the different centers), neurologic improvement, and disappearance of KF ring for those with KF ring present at diagnosis. Treatment adherence was measured through chart review and was based on 24h urine copper and zinc excretion as well as patient reported information throughout the follow up and not in a single clinical visit. Hard outcome measures such as death or need for liver transplantation, were also recorded. The study was approved by the Ethic Committee of each hospital and the Spanish Agency of Medication (AEMS). Data were expressed as median and interquartile range for continuous variables while categorical variables were expressed by absolute and relative frequencies. Continuous variables with Gaussian distributions were compared by Student's unpaired t-test. Categorical variables were compared by the χ2 test. Continuous variables with a non-Gaussian distribution were compared by Wilcoxon rank-sum. Distribution was assessed by normality plots and Shapiro–Wilk test. A p value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

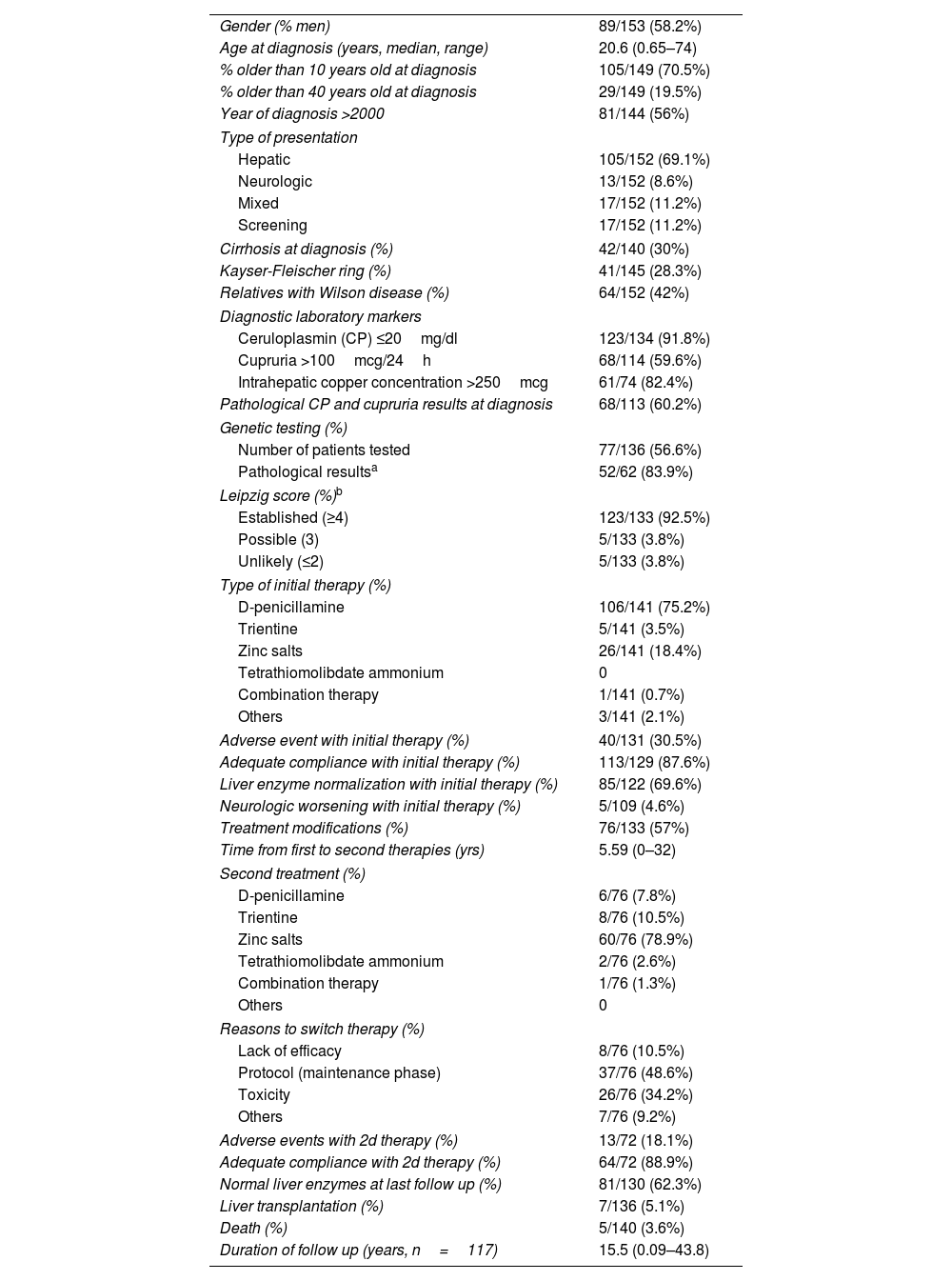

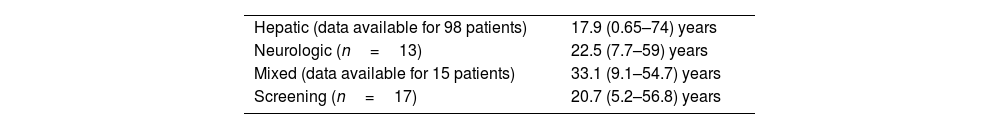

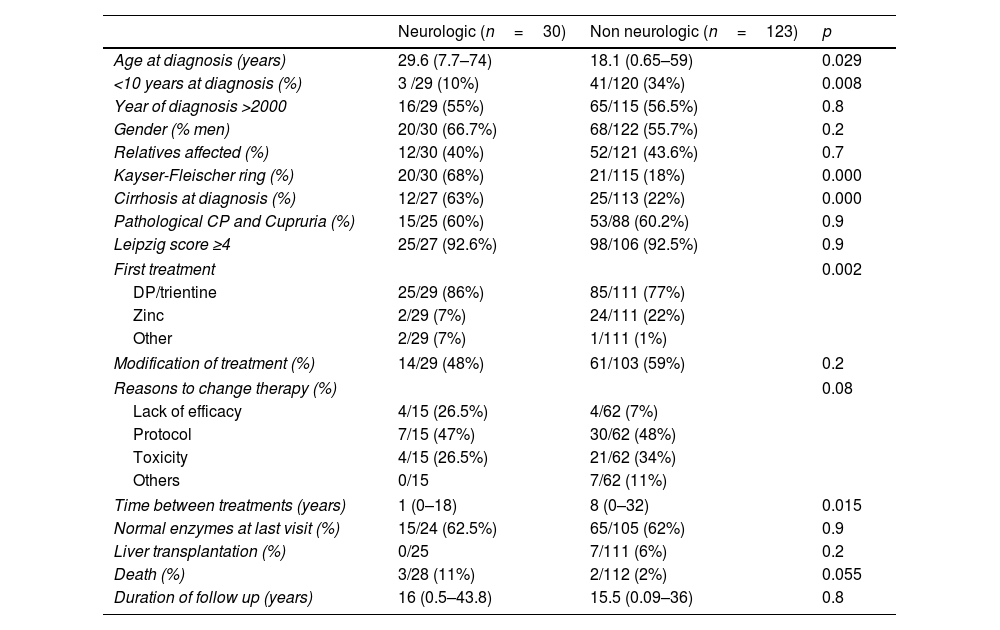

ResultsStudy population (Table 1)The study population included 153 patients followed at 32 different centers, with a significant variability in the number of patients per center, from 1 to 34, recruited in the Comunidad Valenciana (n=48), Madrid (n=24), País Vasco (n=14), Cataluña (n=12), Andalucía (n=12), Castilla y León (n=11), Galicia (n=8), Castilla La Mancha (n=9), Aragón (n=8), La Rioja (n=4) and Islas Baleares (n=3). Most patients were men (58%) with a median age at diagnosis of 20.6 years old (range: 0.65–74) and a median follow-up (FU) since diagnosis of 15.5 years (range: 0.09–43.8). The most frequent form of presentation was hepatic (69.1%) followed by mixed (11.2%) and neurological (8.6%). In the remainder 11.2%, the diagnosis was done through family screening. Median age at diagnosis was lower in the hepatic cases (17.9 years) compared to those with neurological presentation (25.5 years) or mixed cases (33.1 years) without reaching statistical significance (p=0.187) (Table 2). Interestingly those diagnosed in the setting of family screening were diagnosed at a median age of 20.7 years, not different from clinical driven diagnoses. Those diagnosed at ages 10 or below had predominantly a hepatic presentation (79.5%) and only 6.8% had neurological symptoms. KF ring and cirrhosis were present at diagnosis in one third of the cases, respectively. KF rings were found in a significantly higher proportion of those with neurologic presentation than in pure hepatic forms (53.8% of those with neurologic presentation, 76.5% of those with mixed presentation and 20.4% of those with hepatic presentation, p=0.0001) (Table 3). Furthermore, there was also an association with presence of cirrhosis so that KF rings were present in 54.8% of those with cirrhosis at diagnosis as compared to 14.3% of those without (p=0.0001).

Baseline features, treatment, and outcome of the study population (n=153).

| Gender (% men) | 89/153 (58.2%) |

| Age at diagnosis (years, median, range) | 20.6 (0.65–74) |

| % older than 10 years old at diagnosis | 105/149 (70.5%) |

| % older than 40 years old at diagnosis | 29/149 (19.5%) |

| Year of diagnosis >2000 | 81/144 (56%) |

| Type of presentation | |

| Hepatic | 105/152 (69.1%) |

| Neurologic | 13/152 (8.6%) |

| Mixed | 17/152 (11.2%) |

| Screening | 17/152 (11.2%) |

| Cirrhosis at diagnosis (%) | 42/140 (30%) |

| Kayser-Fleischer ring (%) | 41/145 (28.3%) |

| Relatives with Wilson disease (%) | 64/152 (42%) |

| Diagnostic laboratory markers | |

| Ceruloplasmin (CP) ≤20mg/dl | 123/134 (91.8%) |

| Cupruria >100mcg/24h | 68/114 (59.6%) |

| Intrahepatic copper concentration >250mcg | 61/74 (82.4%) |

| Pathological CP and cupruria results at diagnosis | 68/113 (60.2%) |

| Genetic testing (%) | |

| Number of patients tested | 77/136 (56.6%) |

| Pathological resultsa | 52/62 (83.9%) |

| Leipzig score (%)b | |

| Established (≥4) | 123/133 (92.5%) |

| Possible (3) | 5/133 (3.8%) |

| Unlikely (≤2) | 5/133 (3.8%) |

| Type of initial therapy (%) | |

| D-penicillamine | 106/141 (75.2%) |

| Trientine | 5/141 (3.5%) |

| Zinc salts | 26/141 (18.4%) |

| Tetrathiomolibdate ammonium | 0 |

| Combination therapy | 1/141 (0.7%) |

| Others | 3/141 (2.1%) |

| Adverse event with initial therapy (%) | 40/131 (30.5%) |

| Adequate compliance with initial therapy (%) | 113/129 (87.6%) |

| Liver enzyme normalization with initial therapy (%) | 85/122 (69.6%) |

| Neurologic worsening with initial therapy (%) | 5/109 (4.6%) |

| Treatment modifications (%) | 76/133 (57%) |

| Time from first to second therapies (yrs) | 5.59 (0–32) |

| Second treatment (%) | |

| D-penicillamine | 6/76 (7.8%) |

| Trientine | 8/76 (10.5%) |

| Zinc salts | 60/76 (78.9%) |

| Tetrathiomolibdate ammonium | 2/76 (2.6%) |

| Combination therapy | 1/76 (1.3%) |

| Others | 0 |

| Reasons to switch therapy (%) | |

| Lack of efficacy | 8/76 (10.5%) |

| Protocol (maintenance phase) | 37/76 (48.6%) |

| Toxicity | 26/76 (34.2%) |

| Others | 7/76 (9.2%) |

| Adverse events with 2d therapy (%) | 13/72 (18.1%) |

| Adequate compliance with 2d therapy (%) | 64/72 (88.9%) |

| Normal liver enzymes at last follow up (%) | 81/130 (62.3%) |

| Liver transplantation (%) | 7/136 (5.1%) |

| Death (%) | 5/140 (3.6%) |

| Duration of follow up (years, n=117) | 15.5 (0.09–43.8) |

Note: data was not available for all the variables.

Age at diagnosis based on the type of presentation.

| Hepatic (data available for 98 patients) | 17.9 (0.65–74) years |

| Neurologic (n=13) | 22.5 (7.7–59) years |

| Mixed (data available for 15 patients) | 33.1 (9.1–54.7) years |

| Screening (n=17) | 20.7 (5.2–56.8) years |

p=0.187 (Note: data missing in 9 patients).

Differences between neurologic and non-neurologic presentations.

| Neurologic (n=30) | Non neurologic (n=123) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 29.6 (7.7–74) | 18.1 (0.65–59) | 0.029 |

| <10 years at diagnosis (%) | 3 /29 (10%) | 41/120 (34%) | 0.008 |

| Year of diagnosis >2000 | 16/29 (55%) | 65/115 (56.5%) | 0.8 |

| Gender (% men) | 20/30 (66.7%) | 68/122 (55.7%) | 0.2 |

| Relatives affected (%) | 12/30 (40%) | 52/121 (43.6%) | 0.7 |

| Kayser-Fleischer ring (%) | 20/30 (68%) | 21/115 (18%) | 0.000 |

| Cirrhosis at diagnosis (%) | 12/27 (63%) | 25/113 (22%) | 0.000 |

| Pathological CP and Cupruria (%) | 15/25 (60%) | 53/88 (60.2%) | 0.9 |

| Leipzig score ≥4 | 25/27 (92.6%) | 98/106 (92.5%) | 0.9 |

| First treatment | 0.002 | ||

| DP/trientine | 25/29 (86%) | 85/111 (77%) | |

| Zinc | 2/29 (7%) | 24/111 (22%) | |

| Other | 2/29 (7%) | 1/111 (1%) | |

| Modification of treatment (%) | 14/29 (48%) | 61/103 (59%) | 0.2 |

| Reasons to change therapy (%) | 0.08 | ||

| Lack of efficacy | 4/15 (26.5%) | 4/62 (7%) | |

| Protocol | 7/15 (47%) | 30/62 (48%) | |

| Toxicity | 4/15 (26.5%) | 21/62 (34%) | |

| Others | 0/15 | 7/62 (11%) | |

| Time between treatments (years) | 1 (0–18) | 8 (0–32) | 0.015 |

| Normal enzymes at last visit (%) | 15/24 (62.5%) | 65/105 (62%) | 0.9 |

| Liver transplantation (%) | 0/25 | 7/111 (6%) | 0.2 |

| Death (%) | 3/28 (11%) | 2/112 (2%) | 0.055 |

| Duration of follow up (years) | 16 (0.5–43.8) | 15.5 (0.09–36) | 0.8 |

Note: data was not available for all the variables.

CP: ceruloplasmin; DP: D-penicillamine.

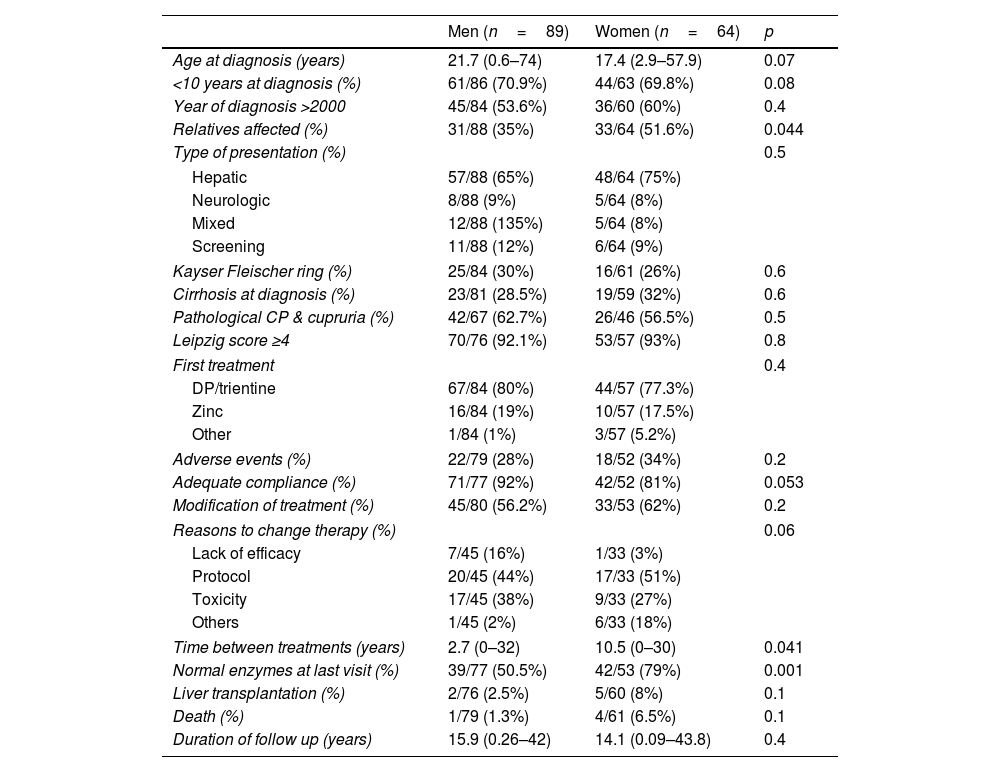

No association was found between sex and the type of presentation, the presence of cirrhosis at diagnosis or the presence of neurological manifestations at diagnosis. Women tended to be slightly younger at diagnosis (17.5yrs vs 21.7yrs, respectively, p=0.07) (Table 4).

Clinical presentation and outcome in men and women.

| Men (n=89) | Women (n=64) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 21.7 (0.6–74) | 17.4 (2.9–57.9) | 0.07 |

| <10 years at diagnosis (%) | 61/86 (70.9%) | 44/63 (69.8%) | 0.08 |

| Year of diagnosis >2000 | 45/84 (53.6%) | 36/60 (60%) | 0.4 |

| Relatives affected (%) | 31/88 (35%) | 33/64 (51.6%) | 0.044 |

| Type of presentation (%) | 0.5 | ||

| Hepatic | 57/88 (65%) | 48/64 (75%) | |

| Neurologic | 8/88 (9%) | 5/64 (8%) | |

| Mixed | 12/88 (135%) | 5/64 (8%) | |

| Screening | 11/88 (12%) | 6/64 (9%) | |

| Kayser Fleischer ring (%) | 25/84 (30%) | 16/61 (26%) | 0.6 |

| Cirrhosis at diagnosis (%) | 23/81 (28.5%) | 19/59 (32%) | 0.6 |

| Pathological CP & cupruria (%) | 42/67 (62.7%) | 26/46 (56.5%) | 0.5 |

| Leipzig score ≥4 | 70/76 (92.1%) | 53/57 (93%) | 0.8 |

| First treatment | 0.4 | ||

| DP/trientine | 67/84 (80%) | 44/57 (77.3%) | |

| Zinc | 16/84 (19%) | 10/57 (17.5%) | |

| Other | 1/84 (1%) | 3/57 (5.2%) | |

| Adverse events (%) | 22/79 (28%) | 18/52 (34%) | 0.2 |

| Adequate compliance (%) | 71/77 (92%) | 42/52 (81%) | 0.053 |

| Modification of treatment (%) | 45/80 (56.2%) | 33/53 (62%) | 0.2 |

| Reasons to change therapy (%) | 0.06 | ||

| Lack of efficacy | 7/45 (16%) | 1/33 (3%) | |

| Protocol | 20/45 (44%) | 17/33 (51%) | |

| Toxicity | 17/45 (38%) | 9/33 (27%) | |

| Others | 1/45 (2%) | 6/33 (18%) | |

| Time between treatments (years) | 2.7 (0–32) | 10.5 (0–30) | 0.041 |

| Normal enzymes at last visit (%) | 39/77 (50.5%) | 42/53 (79%) | 0.001 |

| Liver transplantation (%) | 2/76 (2.5%) | 5/60 (8%) | 0.1 |

| Death (%) | 1/79 (1.3%) | 4/61 (6.5%) | 0.1 |

| Duration of follow up (years) | 15.9 (0.26–42) | 14.1 (0.09–43.8) | 0.4 |

Note: data was not available for all the variables.

CP: ceruloplasmin; DP: D-penicillamine,

Five patients (3.6%) died during the follow up, one due to neurological complications from WD, one from metastatic cholangiocarcinoma, one due to pneumonia, one due to decompensated liver disease and one of unknown cause. Furthermore, 7 additional patients required liver transplantation (Table 1). Of these 2 were done at the time of diagnosis due to fulminant presentation whereas 4 were done in the setting of decompensated cirrhosis (2 very soon after the diagnosis and 2 in the long-term) and one in the setting of paradoxical neurological worsening following inadequate therapeutic compliance.

Diagnostic toolsDiscordant results were observed regarding diagnostic non-invasive laboratory parameters in 39.8% of cases. While ceruloplasmin (CP) levels were decreased in 91.8% of cases, 24h cupruria was greater than 100mcg (40mcg in children)/24h in only 59.6% of patients at diagnosis. Most patients had intrahepatic copper concentration performed with results compatible with WD in 82.4% of cases. In those in whom a biopsy was not performed (16%), the diagnosis was reached through the sum of other results, including genetic evaluation, but diagnostic information was missing in 20 patients in whom a Leipzig score could not be ascertained. An association was found between biopsy performance and date of diagnosis, so that 93.3% of those diagnosed before the year 2000 had a biopsy done for copper quantification compared to 80.3% of those diagnosed in more recent years (p=0.029). For those in whom the information was provided, genetic testing was done in only half of the patients (56.6%) with mutations compatible with WD found in the majority (83.9%). Overall, 92.5% of patients had a Leipzig score of 4 or greater. In 3.8% additional cases (n=5), the Leipzig score was 3 but data on some relevant variables (either urinary copper or intrahepatic copper concentration) were missing. Four of these cases had been diagnosed at an early age and had moved as adults to different Spanish regions. The fifth case corresponded to a patient diagnosed as adult with no genetic testing nor 24 urinary copper results but positive liver copper quantitation and a CP level between 0.1 and 0.2g/dl. The five remaining cases had a Leipzig score (calculated based on information sent to the registry) below 3. These were 5 adults with CP levels between 0.1 and 0.2g/dl, negative cupruria and either lack of additional information (n=2), intrahepatic copper between 0.8 and 4μmol/g but no genetic testing (n=1) or mutation analysis in only 1 chromosome but no data on intrahepatic copper (n=2).

No association was found between sex nor type of presentation and the presence of discordant non-invasive diagnostic tests (Tables 3 and 4).

TherapiesD-penicillamine (DP) and zinc salts (Zn) were the most common initial therapies, used as single agents in 75.2% and 18.4% of patients, respectively. Trientine was used as single initial agent in only 3.5%. Only 0.7% started combined chelator/zinc therapy (Table 1). Zinc salts were used in monotherapy more frequently in pure hepatic presentations (22%) as opposed to neurological or mixed presentations (7%) (Table 3). Yet, when cirrhosis was present zinc monotherapy was seldom used (6% vs 24% if no cirrhosis, p=0.025). Adverse events were reported by 45% of those on zinc salts on monotherapy compared to 29% of those under cupruretic treatments (pNS). Treatment was modified during FU in half of the patients (57%) at a median of 5.59 years (0–32 yrs), mostly due to switch to maintenance therapy (47.4% at a median of 8.4 years, range: 0.06–24.1) or toxicity (33.3%, at a median of 2.29 years, range: 2.3–20). A paradoxical neurological worsening was observed in 4.6% of cases, all under chelators, one in the setting of re-initiation of therapy following compliance issues. Toxicity was the cause of switching therapy in 33% of those started on zinc salts compared to 40% of those started on DP or trientine (pNS). Lack of efficacy was responsible for modification of initial medications in only 10.3% of cases. Second line therapies were mostly based on zinc salts (77.9%), D-penicillamine (7.8%), trientine (10.4%) or tetraothiomolibdate ammonium (2.6%). Despite good adherence referred in most patients both with first- and second-line therapies, up to one third of patients (37.7%) had abnormal liver enzymes at last FU visit after a median of 15.5 (0.09–43.8) years (Table 1). Men had more frequently altered liver enzymes at last follow up than women (49.5% vs 21%, p=0.001) (Table 4), yet lack of compliance was more frequently reported in women (p=0.053). Of note, modification of therapy due to lack of efficacy was more common in men (16% vs 3%, p=0.06). In addition, the absence of mutations in genetic testing was also more frequent among non-biochemical responders (23.8% vs 6.7%, p=0.09). None of the remaining variables analysed including type of therapy, age at diagnosis, type of presentation, presence of KF ring or cirrhosis at diagnosis were associated with liver enzymes profile at last time-point. Overweight and hypertension were more frequently present in non-responder patients yet not reaching statistical significance (p=0.1 and 0.2).

DiscussionThe implementation of national multicenter studies allows the recruitment of an adequate number of patients with rare diseases, such as WD, for which no updated data is available in our country. Particularly, there are no reliable data on its incidence, prevalence, genetic profile, most frequent type of clinical presentation, or type, efficacy, and toxicity of the treatments used.8

Our overall aim was to assess, in a large multicenter WD Spanish study, whether the approach to WD diagnosis and management is homogeneous among centers. The main findings can be summarized as follows: (1) despite strong recommendation from the EU Committee of Experts on Rare Diseases (EUCERD), data collection and registration were found to be clearly insufficient using a retrospective database highlighting the need to create effective prospective registries. In fact, the Spanish Association for the Study of Liver Diseases just approved in 2021 the creation of such registry under its supervision. (2) The phenotype described in our WD population is like that described elsewhere with a slight predominance of men and a younger age at diagnosis in hepatic vs neurological forms1,2; in contrast to recently published data, we did not find an association between sex and the type of presentation14 nor the positivity/negativity of diagnostic non-invasive tools. Whether this is related to the lack of data reported for several patients is still unknown but clearly points to the need to further investigate these potential associations. (3) Classical diagnostic tools are similarly used among centers but there is a significant heterogeneity in the use of genetic tests, only available in 56.6% of the studied population. This may relate to the relatively heterogeneous population in terms of era of diagnosis; indeed, some patients had been diagnosed only one year before inclusion in the database while others had been followed for at least 40 years, with a reduction of invasive liver biopsies performed in recent years, indirectly reflecting a better access to other non-invasive tools including genetic testing. (4) The reliability of current non-invasive tests is suboptimal as previously described1,2,12,17,18 in particular, 24h cupruria was found to be positive in only 59.6% of patients at time of diagnosis. Importantly, the Leipzig score had not been used for diagnosis (i.e. not reported in chart review) in a significant number of cases but based on the data provided (which unfortunately was not always complete), 92.5% of patients had a score considered as “established diagnosis”.18 Enhancing the knowledge of these rare diseases requires a continuous effort given than some physicians may only see one patient in their lifetime. Furthermore, the creation of reference centers for these rare diseases should also be considered by the Spanish authorities. (5) Although genetic testing was done in only half of cases, it was diagnostic in the majority highlighting its usefulness in current algorithms and the recommendation to do it prior to liver copper quantitation in cases of doubts.19 Of note, genetic results should not be used alone as they may not always suffice to diagnose WD in asymptomatic patients.19,20 Unfortunately, we could not assess whether there was a phenotype genotype correlation since the database did not incorporate the type of mutation and only included whether the mutation was present and whether it was detected in both or only one chromosome. (6) Chelating agents, particularly D-penicillamine, were the most common agents used for induction following diagnosis, a finding consistent with the fact that our patients are long-term followed-up patients, recruited in hepatology units and with a greater prevalence of hepatic presentations.1–3 (7) In the long-term though, modification of therapy was frequent, particularly a switch to zinc salt therapy in the context of maintenance phase. Importantly and as previously reported by other authors,15,16 up to one third of patients did not reach absolute normal transaminase values during the maintenance phase despite good “reported” adherence to therapy. We would like to highlight that understanding “adherence” through this type of registries is very difficult. Indeed, it is surprising that 87% were considered as “adherent” to medication by the attending physician, different to what is described for lifetime chronic diseases. There are certainly difficulties in interpreting the results of monitoring tools, particularly for rare diseases in small centers. Self-reporting adherence is in addition known to be a suboptimal method, adding more limitations for interpretation. As such, whether the lack of complete biochemical normalization relates to insufficient activity of zinc as previously suggested in a large European study,15 whether it reflects the difficulty in assessing compliance to therapy or whether it is due to comorbidities such as obesity, dyslipidemia, or diabetes, increasingly present in our WD population, yet still with low rates, is unknown at this time. As expected, compliance was lower in those not reaching a complete biochemical response. Information on additional liver biopsies performed in these patients to understand the lack of complete biochemical response was unfortunately not available in the registry. We did not collect either information on subsequent elastographies. Of note, 3 patients without cirrhosis at baseline have developed decompensated cirrhosis during follow up (2 awaiting LT, one being transplanted). (8) Although not statistically significant, sex differences were present in this study, including lower number and lower age at diagnosis in women and, interestingly greater frequency of altered liver enzymes at last follow despite better “compliance” to therapy in men. As stated before, interpretation of compliance requires finer assessments and while comorbidities (particularly dyslipidemia, data not shown) were more frequently detected in men, these were not significantly associated with biochemical non-response. In essence, we could not find reasons for these trends which should be explored in future studies.

Our study is limited by the retrospective design with missing data in several variables. This was particularly important when trying to calculate retrospectively the Leipzig score. On the other hand, most patients had a hepatic presentation, as the study was performed by a group of hepatologists. The heterogeneous recruitment of cases from 32 different centers may also explain some findings, but due to the high number of centers with variable number of cases per center, an adequate analysis of center effect was not carried out.

ConclusionOur study highlights discordant results regarding standard tests for WD diagnosis, frequent in our multicenter Spanish cohort. This variability may be due to inherent known limitations of the tests and/or lack of reproducibility between laboratories, or alternatively the fact that many diagnoses were made many years before, forcing to carry out invasive techniques in a substantial number of patients. In the current era of genetic testing,17–20 diagnostic in most cases, the role of an invasive biopsy for diagnosis requires re-evaluation. Whether it is still needed to assess the degree of liver damage or whether we can rely on non-invasive methods, such as elastography is still a matter of debate.20,21 Although most patients start treatment with DP, switching to zinc salts due to either maintenance protocol and/or toxicity is very common. In one third of cases, a complete normalization of liver enzymes was not reached, perhaps due to unrelated causes. Sex differences need to be further explored.

Ethical approvalThe study was approved by the Ethic Committee of each hospital and the Spanish Agency of Medication (AEMS). The study was reviewed and approved for publication by our Scientific Committee.

FundingCiberehd is partially funded by the IIS Carlos III. There was no financial support for the conduct of this research and/or preparation of the article.

Conflict of interestMB has consulted for Orphalan and Deep genomic. MV, MC and EM have consulted for Orphalan.