To investigate the mucoadhesive strength and barrier effect of Esophacare® (Atika Pharma SL, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria) in an ex vivo model of gastro-oesophageal reflux.

MethodsAn ex vivo evaluation through the Falling Liquide Film Technique with porcine esophagi was performed, compared to a positive control (Ziverel®; Norgine, Amsterdam), after different washing periods with saline, acidified saline (pH 1.2) and acidified saline with pepsin (2000U/mL).

ResultsThe adhesive mean strength on the oesophageal mucosa of Esophacare was 94.7 (6.0)%, compared to 27.6 (19.1)% of the positive control (p<0.05). These results were homogeneous across the different washes and throughout the tissue. The area covered by 1mL of Esophacare, and its respective persistence after washing was also assessed, yielding a mean global persistence of 74.29 (19.7)% vs. 18.9 (12.3)% for the control (p<0.05). In addition, after 30min exposure to acidified saline with pepsin, Esophacare shows a protective effect on the oesophageal mucosa, detectable histologically: preserved integrity and structure of the apical layers was observed, as well as reduced permeability to the washing solution.

ConclusionsEsophacare shows an adhesive strength close to 100%, irrespective of the washing solution applied or the oesophageal region studied. Histologically, it reduces the abrasive effects of the acidic solution on the oesophageal epithelium, reducing permeability to the washing solution. The results in this ex vivo model of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GERD) support its therapeutic potential.

Investigar la fuerza mucoadhesiva y el efecto barrera de Esophacare® (Atika Pharma SL, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria) en un modelo ex vivo con reflujo gastroesofágico.

MétodosSe realizó una evaluación ex vivo mediante la técnica falling liquide film con esófagos porcinos, en comparación con un control positivo (Ziverel®, Norgine, Ámsterdam, Países Bajos), después de diferentes periodos de lavado con solución salina, solución salina acidificada (pH 1,2) y solución salina acidificada con pepsina (2.000 U/mL).

ResultadosLa fuerza media de adhesión en la mucosa esofágica de Esophacare fue del 94,7% (6,0%), en comparación con el 27,6% (19,1%) del control positivo (p < 0,05). Estos resultados fueron homogéneos en los diferentes lavados y en todo el tejido. También se evaluó el área cubierta por 1mL de Esophacare y su respectiva persistencia tras el lavado: se obtuvo una persistencia global media del 74,29% (19,7%) frente al 18,9% (12,3)% del control (p < 0,05). Además, tras 30 minutos de exposición a una solución salina acidificada con pepsina, Esophacare muestra un efecto protector sobre la mucosa esofágica, detectable histológicamente, con la conservación de la integridad y la estructura de las capas apicales, así como con reducción de la permeabilidad a la solución de lavado.

ConclusionesEsophacare muestra una fuerza adhesiva cercana al 100%, independientemente de la solución de lavado aplicada o de la región esofágica estudiada. Histológicamente, reduce los efectos abrasivos de la solución ácida sobre el epitelio esofágico y reduce la permeabilidad a la solución de lavado. Los resultados en este modelo ex vivo de enfermedad de reflujo gastroesofágico apoyan su potencial terapéutico.

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a frequent clinical problem, associated with a negative impact on quality of life.1,2 GERD is defined as gastro-esophageal reflux that results in disturbing symptoms, like pyrosis or regurgitation, or complications like esophagitis.3,4 The symptoms of GERD are common, and its growing prevalence can reach 30% according to some reports, and the presence of esophagitis, erosion or ulceration is detected in at least one-third of the patients suffering from this condition.3–6

Among the different pharmacological treatments for GERD, surface agents act by protecting the mucosal surface of the stomach and oesophagus from the acidic environment and can be indicated for the alleviation of symptoms.2

Esophacare (Atika Pharma SL) is a drinkable liquid formula designed to exert a protective and restorative action in patients with esophagitis. Esophacare is composed by water, aloe vera gel (AVG) (Aloe barbandesis, Miller), hyaluronic acid (HA), chondroitin sulfate (CS), vitamin C and arabic gum. AVG has shown anti-inflammatory and wound healing activities7 and appropriate physical properties.8–10 HA is effective against oral ulcers,11 and with CS, are natural glycosaminoglycans involved in wound healing.12–15 Vitamin C (l-ascorbic acid) stimulates collagen synthesis and enhances the production of barrier lipids against physical abrasion in vitro.16

The ex vivo model Falling Liquide Film Technique (FLFT) on animal esophagi, is an accepted model of GERD that allows the mucoadhesion and the barrier effect evaluations, with similar tissue damaging characteristics.12–18 Therefore, we evaluated Esophacare following the FLFT in porcine esophagi.

The aim of this study was to assess the efficacy of Esophacare in an ex vivo model of esophagitis.

Material and methodsTested formulationsThe studied formulations were Esophacare® (E), Ziverel® (Z) as positive control, and distilled water (C) as negative control. Z was bought in a local pharmacy; E was provided by the manufacturer. Ziverel® is an oral treatment solution for GERD, developed by Norgine B.V., and mainly composed by HA, CS and poloxamer 407, a thickener. To overcome their lack of colour, products were stained with methylene blue for macroscopic evaluation (5mg:2g) (Panreac-Applichem).12–18

Tissue specimensPorcine esophagi were obtained from freshly sacrificed pigs (Landrace, 20–30kg) and transported on ice in a humidity chamber. Some were used directly and the rest frozen (−20°C).19 These latter were defrosted overnight (4°C). The mucous layer was briefly clean with refrigerated saline (Fisiovet; B-Braun-VetCare) of gross materials (rest of food and blood) and were examined for injuries that could interfere in the evaluations. The muscular part and annexes were dissected. The mucous was briefly rinsed with refrigerated saline.12–18 For each experimental replicate, three adjacent specimens from the same oesophagus (1–1.5cm×15–25cm) were included, one per treatment.

Falling Liquide Film Technique experimentsResearch conditionsTreatments (E, Z, C) were distributed over specimens and simultaneously washed in triplicate (one experiment: three triplicates) (Table 1). Specimens were set in cranio-caudal orientation, at 35° above the horizontal, 37°C, 90% RH and 100rpm.12–25 Products were washed (2mL/min) for 30 or 60min, depending on the procedure, with saline (Fisiovet; B-Braun-VetCare), acid-solution (HCl) (acidified saline 0.1M HCl,pH = 1.2-1.5; HCl 35–38%, LabKem-Labbox) or acid-solution with pepsin (HCl+pepsin) (acidified saline with pepsin 2000U/mL; 0.7FIP-U/mg; Panreac-Applichem).12–18 After optimization, 1μL was established as optimal to evaluate the adhesive strength and 1mL to measure the persistence area and barrier effect.

Falling Liquide Film Technique procedures.

| FLFT | Washing solutions | Replicates |

|---|---|---|

| A (adhesive strength)B (persistence area) | Saline | 3×C |

| 3×Z | ||

| 3×E | ||

| HCl | 3×C | |

| 3×Z | ||

| 3×E | ||

| HCl+pepsin | 3×C | |

| 3×Z | ||

| 3×E | ||

| C (barrier effect) | HCl+pepsin | 3×C |

| 3×Z | ||

| 3×E | ||

Falling Liquid Film Technique (FLFT) procedures, products, washing solutions and replicates. Washing solutions: Saline (NaCl 0.9%); HCl: acidified saline; HCl+pepsin: acidified saline with pepsin. Products: C=control (distilled water); Z=Ziverel; E=Esophacare.

FLFT procedures A and B: 27 specimens were used, in 9 triplicates. FLFT procedure C: 9 specimens were used, in three triplicates.

Twenty-five product samples (1μL) were arranged over the mucosa (25=N0). After washing, the remaining samples were counted (Ns). The mucoadhesive strength (%) was calculated: N0/Ns×100.18–22

Procedure B: persistence area quantificationAfter each product application (1mL), the covered area was photographed before (initial area=A0) and after washing (final area=AF). Images were analyzed (FIJI extension, ImageJ software)26 and areas were confronted (A0−AF, cm2; 100−AF, %).17

Procedure C: barrier effect estimationAfter HCl+pepsin washing (30min), the specimens were fixed (buffered-formalin, 4%, Applichem-Panreac) maintaining their orientation. The samples were assessed in the Veterinary Pathology Service (ULPGC). Two tissue fractions were collected from each sample (cranial/caudal), paraffin embedded and haematoxylin-eosin stained.27

Once processed, the histological sections were randomly chosen and blindly evaluated, by an experienced pathologist (MJC). Initially, the area of interest was defined (cranial or caudal) to determine the barrier effect. Secondly, the severity and the extension of the injuries were estimated, and images were acquired (5× magnification; BX51, Olympus-Corp.).

Statistical analysisResults were presented as mean (SD) or median [min-max], depending on whether normal or non-normal distribution. Student's-t or Mann–Whitney's U tests were used for comparisons (two tailed p<0.05 considered significant) (IBM-SPSS Statistics 20, SPSS Inc.).

ResultsSixty-three tissue specimens were evaluated, 27 per procedures A and B, and 9 in procedure C.

Procedure A: mucoadhesive adhesive strengthE shows an overall adhesive strength of 94.7% (Table 2). The global strength of E did not differ between both acid solutions (p=0.37), but was higher after saline washing, reaching 100% of adhesive strength (p=0.046). No statistical differences were found for the strength between cranial and caudal oesophagus (p=0.69).

Adhesive strength values.

| Washing solutions | Saline (%) | HCl (%) | HCl+pepsin (%) | Global (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Esophacare® | 100 (0)a,b | 89.3 (4.6) | 94.7 (6.1) | 94.7 (6.0) |

| Ziverel® | 41.3 (22.0)* | 14.7 (4.6)* | 26.7 (20.5)* | 27.6 (19.1)* |

| Oesophageal region | Cranial (%) | Caudal (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Esophacare® | 94.52 (6.46) | 95.33 (7.34) |

| Ziverel® | 20.29 (22.10)* | 27.97 (17.59)* |

Adhesive strength (percentage [mean (SD)]), by product, washing solutions and region. Washing solutions: saline (NaCl 0.9%); HCl: acidified saline (saline with HCl); HCl+pepsin: acidified saline with pepsin. Comparisons: *=p<0.05, for Ziverel vs. Esophacare; a,b=p<0.05 comparisons among washing solutions within each product, a=saline vs. HCl, and b=saline vs. HCl+pepsin.

In contrast, Z shows a lower global adhesive strength of 27.6% (p<0.001), for all the washings and oesophageal regions (p<0.05), compared to E (Table 2).

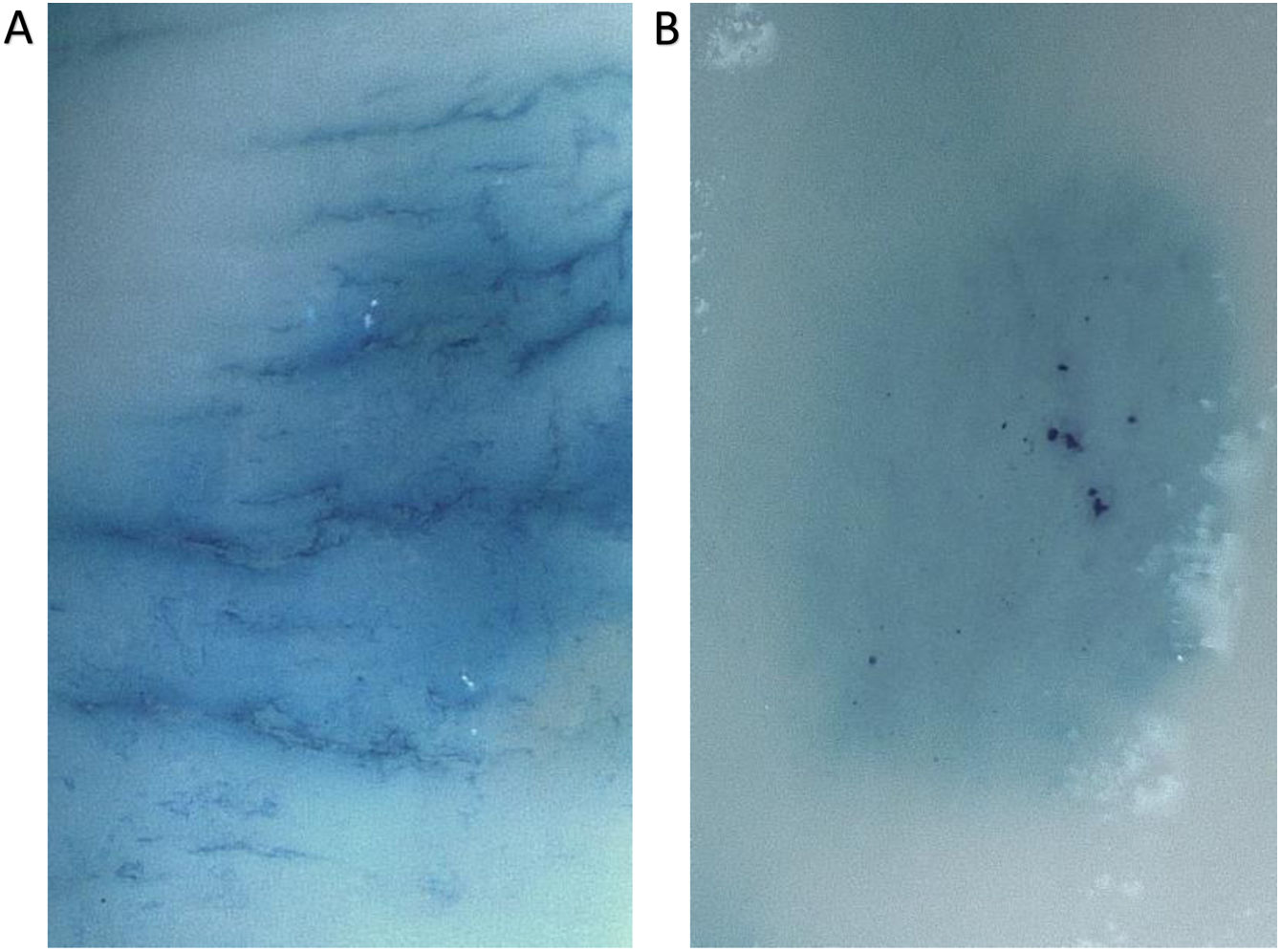

Regarding the negative control, instead of reflecting adherence, it stained the mucosa. This control was included in agreement to previous authors’ methodology.17 However, to avoid misinterpretation, it was excluded from the analysis (procedures A and B). Besides, a specific evaluation was performed to clarify this, where a staining of the tissue (not adherence) by the negative control was confirmed (Fig. 1).

Macroscopic evaluation during adhesive strength determination. (5×; saline washing, 30min). (A) Mucosa stained. After 1μL application of control solution (distilled water with methylene blue), dye diffused between the application spots and margins are lost. (B) Esophacare adherence. A defined oval is seen, apparently protruding from the surface, with undissolved methylene blue crystals. Its location shows the area of application.

No differences were found among the initial surface covered by any of the products (p>0.96). Globally, E shows higher persistence than Z, under all conditions (Table 3).

Persistence area measurements.

| Initial area | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Product | Esophacare® | Ziverel® | Control |

| Area (cm2) | 12.37±1.98 | 12.15±2.19 | 13.02±2.73 |

| Persistence area (%) after washing | Global (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saline | HCl | HCl+pepsin | ||

| Esophacare® | 93.1 [85.3–94.3] | 69.3 (21.4) | 62.6 (20.5) | 74.3 (19.7) |

| Ziverel® | 15.1 [14.4–38.1]* | 20.5 (15.6)* | 13.6 (10.8)* | 18.9 (12.3)* |

| Persistence area (cm2) after washing | Global (cm2) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saline | HCl | HCl+pepsin | ||

| Esophacare® | 11.9 (1.4) | 8.7 (2.5) | 7.64 (5.0) | 9.4 (3.5) |

| Ziverel® | 3.05 (2.0)* | 2.64 (1.9)* | 1.37 (1.0)* | 2.3 (1.6)* |

Persistence area by product after the washing solutions (percentage or cm2, mean (SD) or median [min–max]): Saline (NaCl 0.9%); HCl: acidified saline (saline with hydrochloric acid); HCl+pepsin: acidified saline with pepsin. Comparisons: *=p<0.05, for Ziverel vs Esophacare; a,b=p<0.05 for washings within each product, a=saline vs. HCl, and b=saline vs. HCl+pepsin.

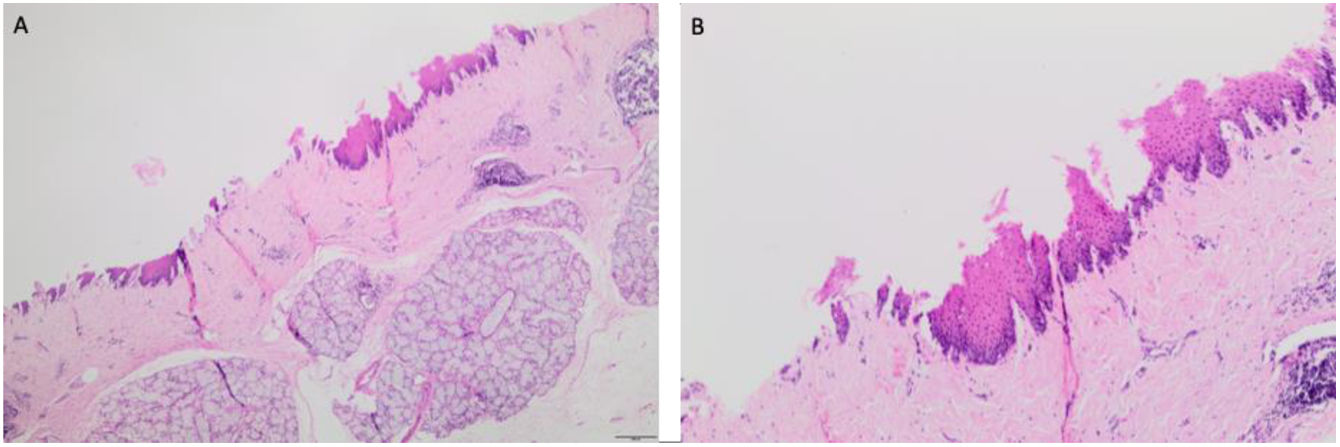

Initially when the area of interest was defined, two very divergent histological scenarios between the cranial and caudal sections were observed. The first, exposed to the initial fall of the washing (HCl+pepsin) showed multifocal areas with disappeared epithelium (Fig. 2). In the caudal region, the epithelium was more preserved but nonetheless showed injuries (Fig. 3): detachment of the epithelium, separated apical layers of epidermis, disintegration of the epithelium outer layers, and thickness of epithelium. Besides, focal cavitated areas and loss of epithelial cell cohesion is observed in lower layers of mucosa. This could be attributed to varied degree of a permeabilization. A descriptive evaluation of severity and extension of the lesions was performed, and representative images of the histological sections were obtained (Fig. 3).

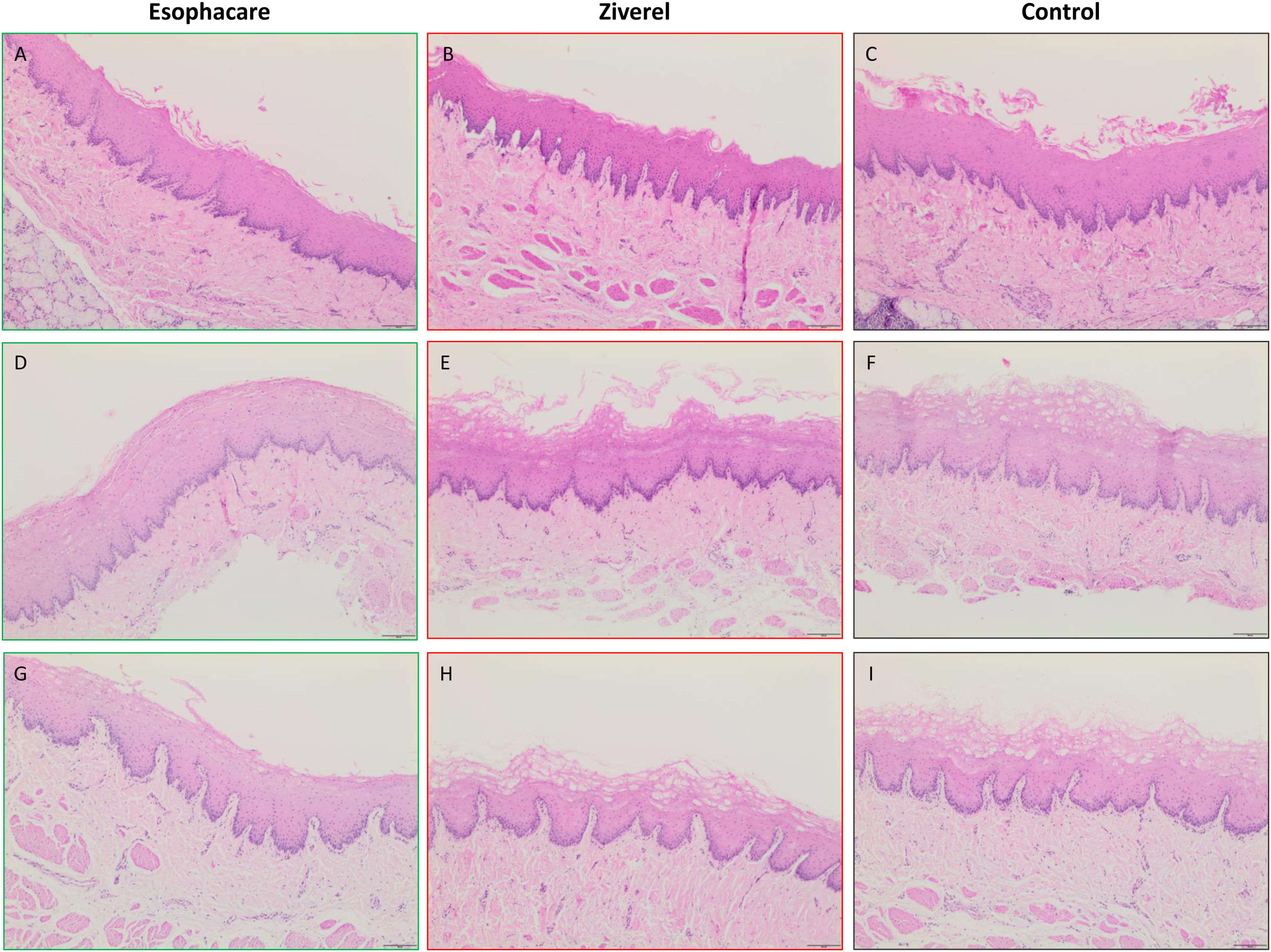

Histological evaluation for the barrier effect estimation ex vivo. Haematoxylin–eosin staining of the oesophageal mucosa after 30min washing with acidified solution and pepsin (10× magnification). Columns 1–3: Esophacare, Ziverel, Control (distilled water). Rows A–H, (experimental replicates): A–C, D–F, G–H. Cell damage in the apical layers of the epithelium was observed with varying affection degrees, as consequence of the abrasive process. The most evident lesion was the disintegration and disorganization of the apical and intermediate epithelial layers (detached layers forming convolutions, losing their dense longitudinal structure) present in B, C, F, H and I, (Ziverel, Control) with complete or partial detachment in some cases (C and E), injury that may decrease the thickness of epithelium (E and H). In contrast, the less affected tissues are A, D, G, (Esophacare), with more preserved architecture and compact appearance at superficial layers. Another remarkable lesion is the cavitated areas due to the epithelial cell cohesion loss (spaces within the flat keratinized stratified epithelium), of variable depth, extent and frequency. In this sense, this lesion was more evident in E, F, H, I, (Ziverel, Control) and slightly evident in D and G (Esophacare). The depth of this lesion is also greater in the same cases, reaching the germinative strata in E, F, H and I, where it seems that this phenomenon spreads linearly, causing group detachments of the upper strata.

The disintegration of the outer layer of the epithelium was the greatest injury to illustrate this analysis. Tissue sections showed a largely homogeneous response between product replicates. In general, the tissues treated with Z and C showed more injuries and lost their normal architecture. Those with E were not exempt from damage, but the epithelium was thicker and more preserved. The superficial layers remained united among replicates and the cavitary areas were more superficial and less extensive (Fig. 3).

DiscussionUsing an ex vivo model of GERD, the present study shows that E displays high adhesive strength and persistence, as well as a barrier effect on the mucosa. In contrast, the positive control exhibited worse performance.

The strength of this study is the minimization of the interferences on each procedure, performed in triplicate, with adjoining sections of the same organ, to test products simultaneously under similar conditions. In each triplicate, the treatments were applied in rotating order for the three specimens. The ex vivo conditions were adapted aiming to approach them to those of the clinical application.12–23 In line with this, previous studies left the product acting on the mucosa to adhere for variable periods (5–30min). The present procedures were assessed immediately. In addition, previous authors determine adhesive strength only for saline washing,18 here, acidified solutions were included, and have expressed a mean global value for this strength for more realistic determinations. For the persistence area, a quantification through image analysis software was also included to increase accuracy.17,26 Finally, the histological assessment was blinded for the different treatments and washing solutions.

Despite the methodological aspects considered, we acknowledge that the main limitation is the lack of an adequate negative control. This limitation was not detected during the performance, until subsequent analysis, as procedures A and B were performed at once in a short period of time. However, previous studies have not reported this issue (in text or photo), though the addition of methylene blue to the negative control is common.

The preclinical soundness of the present ex vivo model has been validated in subsequent clinical trials12–28 and many of the main components of surface agents for GERD, have been evaluated by FLFT.19–22 In the present study, the effectiveness and superiority of E versus Z was evidenced during the FLFT, for all the conditions, what was also confirmed histologically.

Z is used as a liquid treatment in patients with GERD, that shares components of similar formulations, as HA and CS, and its adherence capacity is based on the use of poloxamer 407. Z was utilized as positive control due to the shared components, indication and availability. In the case of E, the main differentiating ingredients with respect to the Z formula are AVG, vitamin C and Arabic gum. The superior adhesive capacity in the case of E might be explained by individual or by the joint interaction of the described ingredients, however specific studies are needed.

The histological findings provide an idea of the protection exerted by E. If used in patients with oesophagitis, mucosal healing could be facilitated by the protection exerted by this product. However, this ex vivo evaluation do not consider the full effects of the products assessed and is focused on some mechanisms. These experiments aim to mimic what happens in vivo but cannot replace randomized clinical trials.

ConclusionsBased on the results obtained, E shows an adhesive strength close to 100%, irrespective of the washing solution applied or the oesophageal region studied. Furthermore, the persistence area after the washing solutions, was also high (74.29% of the initially covered area), and this value was not affected by the different washing solutions used. Finally, histologically, E reduces the abrasive effects of the acidic solution on the oesophageal epithelium, preserving its thickness and the integrity of its apical layers, as well as reducing permeability to the washing solution. The results in this ex vivo model of GERD support the potential of E as a treatment for this disease.

FundingThis work was requested and funded by Atika Pharma SL.

Conflict of interestThe authors designed and performed the experiments, analysed the results and wrote the manuscript. The funders approved the study protocol and participated in the decision to publish the results. They had no role in the performance of the experiments, the analysis of the results or the preparation of the manuscript.

We thank Laura Rodrigo for her technical support in the lab. We thank the staff of the Island Slaughter House of Gran Canaria, especially Clara Padilla and Yeray Macías for their patience, kindness and support in the provision of the oesophagi.