A significant percentage of patients coinfected with hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis D virus (HDV) are undiagnosed. Coinfected patients progress to advanced liver disease faster than HBV monoinfected patients, thereby consuming more healthcare resources. The aim was to perform an analysis to determine the cost of hidden HDV infection in Spain.

MethodsAn analytical model was developed to estimate the prevalence of hidden HDV infection with/without advanced liver disease at the time of diagnosis. An epidemiological flow chart was established to quantify undiagnosed chronic hepatitis D patients. The percentages of patients with compensated cirrhosis (CC), decompensated cirrhosis (DC), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and requiring liver transplantation (LT) and their annual costs were subsequently obtained from the literature. Direct healthcare costs were considered within a time horizon of 1 year. For patients without advanced disease, the consumption of healthcare resources was obtained from an experts panel.

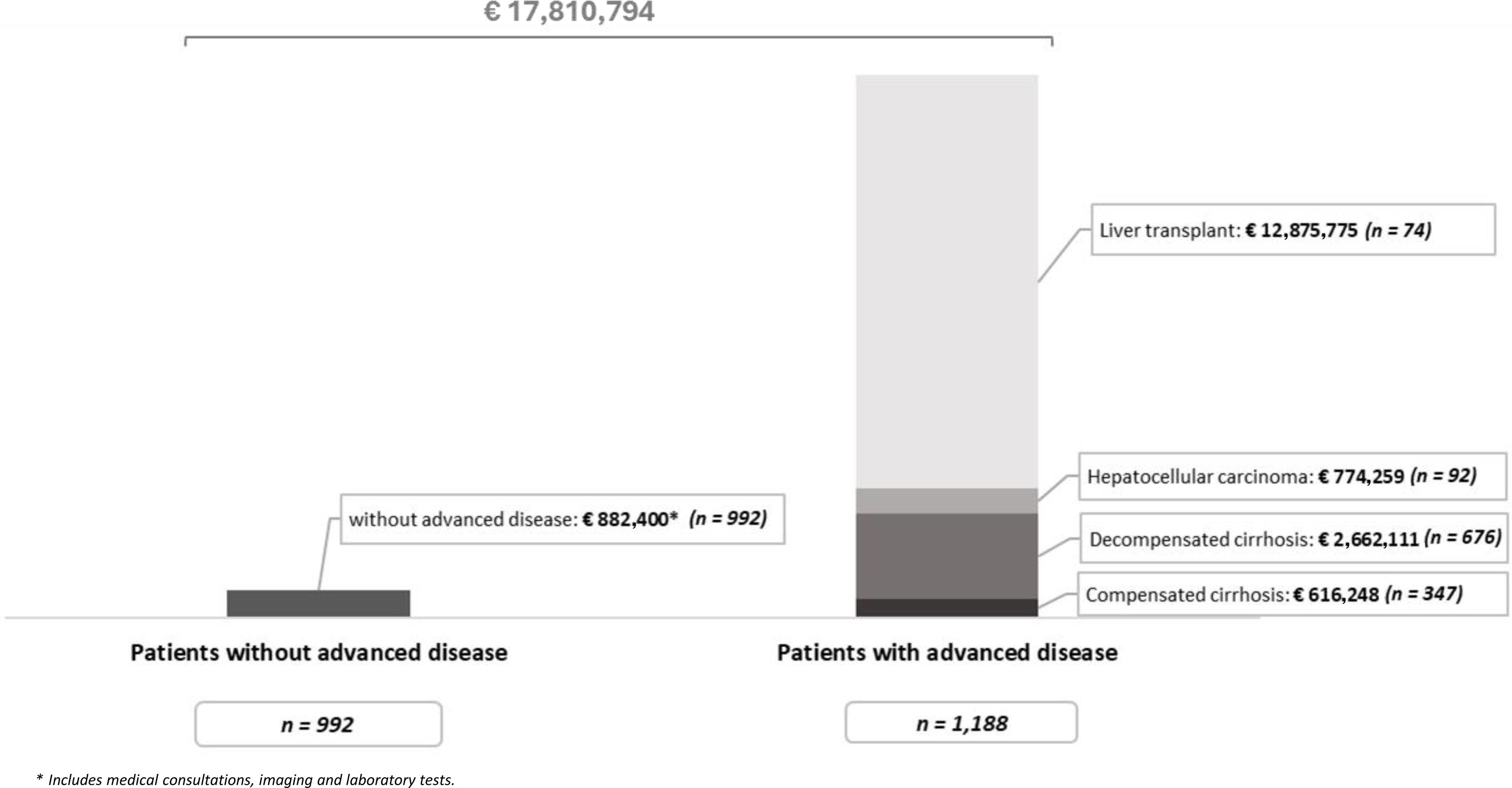

ResultsA total of 2180 patients with hidden HDV infection were estimated; of these, 1188 (54%) had advanced liver disease (29%-CC, 57%-DC, and 8%-HCC) or underwent LT (6%), and 992 (46%) patients did not have advanced disease. The total annual cost of hidden HDV would be € 17.8million (€ 16.9million with advanced disease and € 882,400 for those without).

ConclusionsHidden HDV infection represents a high economic burden in Spain due to the rapid progression of liver disease in affected patients. These results highlight the importance of early diagnosis to prevent future clinical and economic burden related to liver disease progression.

Un porcentaje significativo de pacientes coinfectados por el virus de la hepatitis B (VHB) y el virus de la hepatitis delta (VHD) están sin diagnosticar. Estos pacientes evolucionan a enfermedad hepática avanzada más rápido que los monoinfectados, generando mayor consumo de recursos sanitarios. El objetivo fue realizar un análisis para determinar el coste de la infección por VHD oculta, en España.

MétodosSe desarrolló un modelo analítico para estimar la infección oculta por VHD con/sin enfermedad hepática avanzada en el momento del diagnóstico. Se estableció un flujo epidemiológico para cuantificar a pacientes VHD crónicos sin diagnóstico. El porcentaje de pacientes con cirrosis compensada (CC), cirrosis descompensada (CD), carcinoma hepatocelular (CHC) y trasplante hepático (TH) y su coste anual se obtuvo de la literatura. Se consideraron los costes directos sanitarios en un horizonte temporal de un año. En pacientes sin enfermedad avanzada, el consumo de recursos se obtuvo de un panel de expertos.

ResultadosSe estimaron 2.180 pacientes con infección por VHD oculta; de estos, 1.188 (54%) tenían enfermedad hepática avanzada (29%-CC, 57%-CD, 8%-CHC) o recibieron TH (6%), y 992 (46%) sin enfermedad avanzada. El coste total anual del VHD oculto supondría 17,8 millones de€ (16.900.000€ con enfermedad avanzada y 882.400€ no).

ConclusionesLa infección por VHD oculta representa una elevada carga económica en España, debido a la rápida progresión de la enfermedad hepática. Estos resultados ponen en valor la importancia de realizar un diagnóstico temprano para prevenir la futura carga clínica y económica relacionada con el avance de la enfermedad hepática.

Hepatitis D is a liver disease caused by infection with the hepatitis D virus (HDV). HDV is an incomplete RNA virus that requires the presence of the hepatitis B virus (HBV) for its replication and transmission.1,2 The prevalence of HDV infection varies significantly across different regions. It is estimated that between 4.5% and 14.57% of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)-positive patients worldwide are coinfected with HDV, or between 12 and 20million people.1,3

The prevalence of HDV infection is linked to the implementation of vaccination programs against HBV.4 Spain is a country with high vaccination coverage (approximately 95%),5 which has lowered the prevalence of HDV infection. However, despite this coverage, HDV infection prevalence is estimated to be approximately 5.2%6 among those infected with HBV, although recent studies have shown that coinfection could be underdiagnosed7–9 and be at least two or three times greater than estimated.8

Chronic hepatitis D, despite being one of the less common forms of hepatitis, is considered the most aggressive form of viral hepatitis. Compared with HBV monoinfected patients, coinfected patients have a faster progression to cirrhosis10 and an increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and mortality.1,11–13 It is estimated that between 15% and 20% of patients with chronic hepatitis D progress to cirrhosis after two years and have a 3-fold greater risk of suffering from HCC.14,15 In addition, this risk also generates an increase in the number of liver transplants with respect to monoinfection.16,17

However, the burden of HDV infection is underestimated, mainly because of the limited use of HDV antibody (anti-HDV) testing in HBsAg-positive patients.7 As recommended by the clinical guidelines18 and scientific societies,19 standardized performance of HDV-RNA tests is necessary for HDV infection diagnosis. Not performing HDV reflex testing to all HBsAg positive patients and HDV-RNA testing to all delta antibody positive patients favors underdiagnosis and leads to an increase in occult infection and the late diagnosis of patients.4,20

On the other hand, as a consequence of the increase in the health care burden due to the high risk of developing advanced liver disease (hereafter, advanced disease) and undergoing liver transplantation, HDV infection is associated with a significantly greater economic burden than is HBV monoinfection.21 This means that HDV infection management is associated with greater consumption of health resources and higher costs than is HBV monoinfection,21,22 thereby being a problem for health care systems.

Therefore, the objective of this analysis was to determine the cost generated as a consequence of hidden HDV infection and progression to advanced disease in Spain.

MethodsA cost analysis model was developed to estimate the burden of disease associated with or without advanced disease and its cost at the time of diagnosis in patients with hidden HDV infection in Spain based on data extracted from the literature and whose parameters were validated by a panel of experts. Patients with hidden infections were defined as patients with chronic hepatitis D, that is, those who were HDV-RNA positive, that was not diagnosed by the health care system.

Epidemiological flow chartTo quantify the number of patients with chronic hepatitis D without a diagnosis, an epidemiological flow chart was created on the basis of the total number of adults (≥18 years) residing in Spain,23 which was estimated to be 39,495,281 individuals in 2022. The prevalence of HBsAg positivity (0.385%) was established as the average prevalence reported in the 2nd seroprevalence study in Spain24 and an observational study,25 and it was considered that 46.3% of the population was aware of their HBV infection status.25 On the other hand, it was estimated that 82% of patients who were HBsAg positive were not tested for anti-HDV.26 The prevalence rates of anti-HDV and HDV-RNA positivity considered in the analysis were 5.2%9 and 65%, respectively. In addition, the percentage of patients with a positive anti-HDV test but without viral load assessment was considered to be 53.5%27 (Fig. 1).

To measure the impact of HDV infection, the differences between the rates of the occurrence or absence of compensated cirrhosis (CC), decompensated cirrhosis (DC) and HCC and the need for liver transplantation (LT) in HBV monoinfected and coinfected patients (HBV/HDV) were measured28 (Table 1).

Proportion of patients with chronic hepatitis D who develop advanced disease.

| Percentage (%)28 | |

|---|---|

| Compensated cirrhosis | 15.9 |

| Decompensated cirrhosis | 31.0 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 4.2 |

| Liver transplant | 3.4 |

Differences in the incidence of cirrhosis and liver complications between patients with HBV monoinfection and those coinfected with HBV according to Buti et al., 2023.28

In accordance with the perspective of Spain's National Health System (SNS), only the direct health care costs used by a patient with chronic hepatitis D, with or without advanced disease, were considered within a time horizon of 1 year.

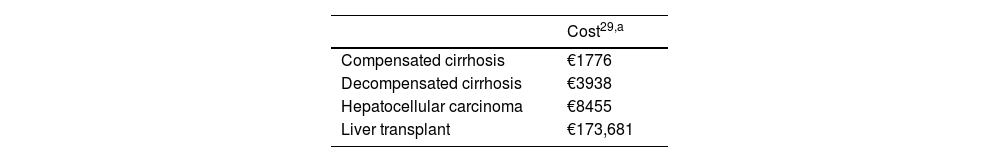

The costs associated with CC, DC, HCC and LT were obtained from the literature (Table 2).29 The resources consumed by a patient with chronic hepatitis D without advanced disease were obtained from the disaggregated consumption of medical consultations, imaging tests and laboratory tests, according to the usual clinical practice provided by the panel of experts (Table S1), the unit costs from a national database30 and from the literature.31 All costs were updated according to the consumer price index (CPI)32 and are expressed in euro values for the year 2023 (€, 2023).

Sensitivity analysisTo evaluate the robustness of the analysis, a deterministic univariate sensitivity analysis (SA) was performed with different scenarios, with the prevalence of patients with HBsAg set between 0.22%24 (SA1) and 0.55%25,33 (SA2); the percentage of patients with HBsAg positivity diagnosed set between 34.85%25 (SA3) and 58.08%25 (SA4); the percentage of patients screened for HDV infection as 92.7%7 (SA5); the percentage of anti-HDV-positive patients as 8.10%7 (SA6); the percentage of anti-HDV-positive patients without an HDV-RNA-positive test as 33.0%26 (SA7); the percentage of patients with HDV-RNA-positive as 30.0% (SA8) and 35.0% (SA9); the percentage of patients with chronic hepatitis D presenting CC as 27.4%12 (SA10), DC as 24.0%12 (SA11) or HCC as 24%12 (SA12); and the percentage of chronic hepatitis D patients who underwent LT as 13.14%12 (SA13).

ResultsWith the available data, it was estimated that approximately 2180 patients currently have hidden HDV infection in Spain, of those 1188 (54%) have advanced liver disease at the time of diagnosis and 992 (46%) do not. According to our estimates, of the patients with advanced disease, 347 (29%) patients will develop CC, 676 (57%) patients will develop DC, 92 (8%) patients will develop HCC, and 74 (6%) patients will require LT.

Considering a time horizon of 1 year, the total annual cost generated by the 992 patients with hidden HDV infection who have not developed advanced disease at the time of diagnosis will be € 882,400. The development of advanced disease involves a total annual cost of € 16,928,393 (Fig. 2).

The total annual cost of hidden HDV infection will be € 17,810,794 (95% associated with advanced disease), assuming an average annual cost per patient of € 8168.

Sensitivity analysisThe different deterministic SA related to the prevalence or diagnostic parameters revealed variability in the number of patients with hidden HDV infection, which was estimated to be between 1006 and 3396 patients. This variation translates into a total annual cost due to hidden HDV infection of between € 8.220.366 and € 27,743,736 (Table 3). The parameters with the greatest influence on both the number of patients and the costs were mainly an increase in the number of patients who were HBsAg positive and who were HDV-RNA-positive.

Univariate sensitivity analysis.

| Patients | Cost | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA scenario | Original value | Without advanced disease | With advanced disease | Total with hidden HDV infection | Without advanced disease | With advanced disease | Total with hidden HDV infection |

| Base case | 992 | 1188 | 2180 | €882,400 | €16,928,393 | €17,810,794 | |

| SA1: Patients with HBsAg positivity (0.2%) | 0.385% | 567 | 679 | 1246 | €504,229 | €9,673,367 | €10,177,596 |

| SA2: Patients with HBsAg positivity (0.6%) | 1417 | 1698 | 3115 | €1,260,572 | €24,183,419 | €25,443,991 | |

| SA3: Patients with HBsAg positive diagnosed (34.9%) | 46.3% | 747 | 894 | 1641 | €664,183 | €12,741,998 | €13,406,180 |

| SA4: Patients with HBsAg positive diagnosed (58.1%) | 1245 | 1491 | 2735 | €1,106,908 | €21,235,444 | €22,342,352 | |

| SA5: Patients screened for HDV infection (92.7%) | 82.0% | 1046 | 1253 | 2299 | €930,315 | €17,847,603 | €18,777,918 |

| SA6: Anti-HDV-positive patients (8.1%) | 5.2% | 1545 | 1851 | 3396 | €1,374,508 | €26,369,228 | €27,743,736 |

| SA7: Anti-HDV-positive patients without HDV-RNA+ test (33.0%) | 53.5% | 952 | 1140 | 2093 | €846,866 | €16,246,676 | €17,093,541 |

| SA8: HDV-RNA-positive patients (30%) | 65% | 458 | 548 | 1006 | €407,262 | €7,813,104 | €8,220,366 |

| SA9: HDV-RNA-positive patients (35%) | 534 | 640 | 1174 | €475,139 | €9,115,289 | €9,590,427 | |

| SA10: Patients with compensated cirrhosis (27.4%) | 15.9% | 741 | 1439 | 2180 | €659,376 | €17,374,107 | €18,033,483 |

| SA11: Patients with decompensated cirrhosis (24.0%) | 31.0% | 1145 | 1036 | 2180 | €1,018,154 | €16,327,271 | €17,345,426 |

| SA12: Patients with HCC (4.5%) | 4.2% | 986 | 1195 | 2180 | €876,582 | €16,983,697 | €17,860,280 |

| SA13: Liver transplantation patients (13.1%) | 3.4% | 780 | 1401 | 2180 | €693,453 | €53,824,523 | €54,517,976 |

SA: sensitivity analysis; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; HDV: hepatitis D virus.

On the other hand, an increase in the percentage of patients with CC, DC or HCC did not have a great impact on economic results, except if we increased the number of patients requiring LT, which increased the total cost by 33% (€ 54,517,976).

DiscussionPatients with hepatitis D represent a significant clinical and economic burden given the rapid progression of the disease and its severity.21 This analysis highlights an important part of that economic burden.

The analysis revealed a considerable number of patients with hidden HDV infection, which, in turn, generated high costs for the health care system, mainly due to progression to advanced disease or the need for LT (95%), which may be associated with late diagnosis. These results could vary due to the lack of information on the prevalence and diagnosis of the infection. For this reason, different SA were carried out, which revealed that a decrease or increase in these parameters would cause the total cost to oscillate between € 8,220,366 and € 54,517,976, assuming a great impact on health care budgets.

To our knowledge, this is the first analysis to evaluate the cost of hidden hepatitis D infection; therefore, we cannot compare our results with those of other studies. Although we cannot make a direct comparison, we can determine the magnitude of the clinical and economic burden of these patients by examining the results of an analysis that estimated the impact of performing the reflex test and concluded that it would generate savings of approximately € 36million in a median follow-up of 8 years by avoiding the development of liver complications after diagnosis34 in 35–38% of patients.

One of the strengths of the analysis is that only the development of cirrhosis, complications and the need for LT due to hepatitis D were included, avoiding an overestimation of costs. Notably, in patients with other infections, the progression of liver disease may not be due to HDV infection but rather to HBV infection. To avoid this, references were used where coinfected and monoinfected patients were evaluated separately, and the results were compared. This also conditions the results of the analysis and was therefore included in the SA. The results of these analyses caused a variation in the total cost generated by the progression of liver disease of between € 17,345,426 and € 54,517,976 as a result of the increase in patients requiring LT. This is because, in the base case, a low percentage of patients would require LT, but there are studies that show that this percentage could be greater.12 However, these values are in line with those in clinical practice.

A limitation of the analysis is that hidden HDV infection was not considered among HBsAg-positive patients who were not diagnosed. The inclusion of these patients in the analysis would have generated an increase in the total cost. Similarly, only the state of health in which the patient was at the time of diagnosis, that is, whether the disease had advanced, was considered in the analysis and the economic burden was calculated by applying the cost to the management of that state. Other types of costs, such as visits to primary care physicians, hospitals or emergency rooms, as well as other tests performed on patients during their disease progression without knowledge of the infection, were not considered because this information was not available. In future studies, the cost of late diagnosis of a patient with hepatitis D should be analyzed while considering all the costs associated with hidden infection.

To prevent hidden HDV infection, measures aimed at broadening its diagnosis are necessary. HBV/HDV coinfection can worsen liver disease compared with monoinfection28 and even cause symptoms in asymptomatic patients, resulting in increased consumption of resources and health care costs. Since HDV infection occurs only in individuals with hepatitis B, one measure to broaden diagnosis would be to extend HDV testing to all HBsAg-positive individuals to detect coinfection and give patients the option for treatment. Many of these patients who are already in the system because of their HBV infection do not have a diagnosis of hepatitis D. There are discrepancies between whether the tests should be performed in all HBsAg-positive patients, as suggested by the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) guidelines,18,33 or only those with risk factors, as recommended by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD).35 A previous study revealed that if the diagnosis is made only on the basis of risk factors, 18% of infected patients36 would go undiagnosed. This loss would cause a high proportion of these patients to have developed cirrhosis at the time of diagnosis, that is, while the infection is hidden.36 Therefore, the management of the infection is more expensive. Likewise, although clinical guidelines recommend annual HDV screening for HBsAg-positive patients with high-risk practices,18,19 performing HDV screening of all infected patients, in addition to enabling the diagnosis of superinfections in asymptomatic patients, would help prevent the development of cirrhosis.37

Another way to ensure the diagnosis of hepatitis D would be to perform HDV reflex testing for all HBsAg-positive individuals and even the double reflex test, which also includes the HDV-RNA test, for all anti-HDV-positive patients. This type of test has been shown to identify more cases of infection and increase linkage to treatment in the health care system,38–40 as well as to avoid future costs of the disease.34 In addition, reflex tests would avoid specialist decision bias on whether to carry out the HDV test.40,41

Additionally, it is important to make health professionals aware of the severity of the infection and the importance of diagnosis to access treatment given the rapid progression of the disease, unlike in monoinfected patients. Patients with undetectable RNA have been shown to have a lower risk of progressing to liver disease and even death.42 Currently, treatment with bulevirtide is available, and its efficacy is based on slowing the progression of the disease,43 further highlighting the importance of detection and linkage to treatment.

ConclusionsThe results of this study demonstrate the high economic impact of hidden HDV infection in Spain due to the rapid progression of liver disease. Highlighting the importance of performing a hepatitis Delta reflex test for all patients with Hepatitis B (HBsA), given the aggressiveness of the disease, in order to increase early detection of HDV and prevent future clinical and economic burden, as treatment is now available for the management of hepatitis Delta.

AuthorshipRDH, LSO and MAC development the model, reviewed the scientific literature, performed the analyses and drafted the manuscript. XF, MR and HC validated the model structure and the inputs and provided information about the clinical management of hepatitis D patients. All the authors contributed to interpretation of the results and reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Artificial intelligence (AI)During the preparation of this paper, the author(s) didn’t used of AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process in their manuscript.

FundingThe study was funded by Gilead Spain Sciences.

Conflict of interestXF has received honoraria for participating in advisory meetings from Gilead and for speaking engagements from AbbVie. MR has received honoraria for speaking engagements from Gilead. HC is employer of Gilead Sciences Spain and had declared that no competing interests exist. RDH, LSO and MAC are employees of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research Iberia (PORIB), a consulting firm specializing in the economic evaluation of health care interventions that has received financing from Gilead Sciences Spain for the development of the project that is not conditional upon the results.