In Latin America and Colombia there are few studies about the clinical and therapeutic characteristics of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). The objective of this study is to obtain an approximation to these data from a sample of patients from different reference centres in Colombia.

Patients and methodsCross-sectional study in adult and paediatric patients, with IBD, attended ambulatory in 6 institutions in different cities, between 2017 and 2020 information was collected on different dates, about demographic, clinical, and therapeutic aspects.

ResultsSix hundred and five subjects, 565 (93.4%) adults, mean age 43 years (SD 12.78), 64% with ulcerative colitis (UC). The age at diagnosis of UC was 41.9 years, while in Crohn’s disease (CD) it was 47.9 years. In UC, there was greater left involvement (47.2%), and in CD, 42.8% ileocolonic (L3). More than 50% were in mild activity or clinical remission. In UC, the biologic requirement was 27.2%, while in CD, 78%. Overall hospitalisation requirement was 39.5%, and the need for surgery was 37.5% in UC and 62.5% in CD. Also, 40 pediatric patients, 90% female, with UC being more frequent (80%). In UC, 83.3% presented extensive colitis, and in CD, all with ileocolonic localization (L3). More than 95% were in mild activity or remission. Biologic therapy was required in 16.6% and 75% for UC and CD, respectively. The frequency of hospitalisations and surgery was 2.7%.

ConclusionsThis study shows some unique characteristics of patients with IBD in Colombia. An earlier diagnosis is required, with a better therapeutic approach.

En Latinoamérica y Colombia hay pocos estudios acerca las características clínicas y terapéuticas de pacientes con enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal (EII). Se plantea como objetivo obtener una aproximación a dichos datos a partir de una muestra de pacientes de diferentes centros de referencia en Colombia.

Pacientes y métodosEstudio de corte transversal en pacientes adultos y pediátricos, con EII, atendidos ambulatoriamente en seis instituciones en diferentes ciudades, entre 2017–2020 se recolectó información en fechas distintas, acerca aspectos demográficos, clínicos y terapéuticos.

ResultadosSeiscientos cinco sujetos, 565 (93,4%) adultos, edad promedio de 43 años (DE 12,78), 64% con colitis ulcerosa (CU). La edad de diagnóstico de CU fue 41,9 años, mientras en enfermedad de Crohn (EC) fue 47,9 años. En CU, mayor compromiso izquierdo (47,2%), y en EC, 42,8% ileocolónico (L3). Más de 50% en actividad leve o remisión clínica. En CU, el requerimiento de biológico fue de 27,2%. mientras en EC, 78%. Requerimiento global de hospitalización en 39,5%, y necesidad de cirugía, de 37,5% en CU y 62,5% en EC. También, 40 pacientes pediátricos, 90% mujeres, siendo CU más frecuente (80%). En CU, 83,3% presentaron colitis extensa, y en EC, todas con localización ileocolónica (L3). Más de 95% en actividad leve o remisión. Requerimiento de biológico, en 16,6 y 75%, para CU y EC, respectivamente. La frecuencia hospitalizaciones y cirugía fue 2,7%.

ConclusionesEste estudio muestra algunas características únicas de los pacientes con EII en Colombia. Se requiere de un diagnóstico más temprano, con un mejor enfoque terapéutico.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) includes two entities: ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD), the aetiology of which is multifactorial, involving genetic, environmental and immunological factors. These entities entail chronic, recurrent inflammation of different degrees of severity in the intestinal tract, and a clinical course with relapses and remissions throughout the course of the disease, as well as potential involvement of other organs.1,2 Additionally, IBD has significant morbidity and mortality rates and high socioeconomic costs, since it is an entity that appears early in life in a person’s most productive years.3

IBD is a global disease and its evolution can be classified into four epidemiological stages, including emergence, acceleration in incidence, compounding prevalence, and prevalence equilibrium. Latin America is in the second stage known as acceleration in incidence, which is associated with a rapid increase in incidence and low prevalence.4 The appearance of IBD in the 20th century in Latin America was documented through a systematic review of clinical and epidemiological studies of IBD, with a rapid increase in its incidence in the 21st century, and also a notable heterogeneity between countries in relation to factors such as historical colonisation, culture, socioeconomic status, genetic background, lifestyle, and diet.5 Likewise, in these regions, the description of the clinical characteristics and treatment of patients with IBD continues, including: penetrating behaviour in CD, steroid dependence, resistance to steroids, intolerance to thiopurines, presence of extraintestinal manifestations and requirement for surgery, hospitalisations for IBD and family history of IBD. The factors associated with the use of biologic therapy were: the presence of pancolitis in UC, penetrating disease in CD, resistance and dependence on steroids, the presence of extraintestinal manifestations and the need for surgery.6–9 From what has been seen, the observed IBD phenotypes vary slightly between countries, but are consistent with what has been described in other regions of the world.6,9

Colombia, in particular is classified as a nation with an intermediate prevalence of IBD with an increase in the burden of the disease, possibly related to changes in environmental factors, such as increasing urbanisation, an increase in obesity, and an increase in fast food consumption.10,11 And this data includes information from the study by Fernández Ávila et al.,11 in which IBD prevalence was estimated at 87 cases per 100,000 inhabitants, it being more frequent in women, with a prevalence of CD and UC of 17 per 100,000 inhabitants and 113 per 100,000 inhabitants, respectively; and from the study by Juliao-Baños et al.,10 which reported an increase in incidence from 6.88/100,000 in 2010 to 7.04/100,000 in 2017, with a higher risk of disease in women, and in ages 40–59 years of age. However, there is still a knowledge gap regarding the clinical and therapeutic characteristics of patients with IBD at a national level, and the scarce information that exists comes mainly from the adult population, without reliable data for the paediatric population. It is important to understand the differences in IBD presentation in different geographic regions due to the impact of the disease on health systems, as well as to determine appropriate prevention and treatment strategies. Therefore, studies are required in which the affected population is characterised taking into account the clinical phenotypes and the therapeutic aspect, as well as information that includes paediatric patients. The main aim of this study is to describe the demographic characteristics, clinical presentation, phenotype, and treatment in IBD patients based on information collected from patients diagnosed with IBD from six IBD reference gastroenterology centres in three major cities.

Patients and methodsStudy design and data extractionA cross-sectional, descriptive, observational study was conducted using convenience sampling in which the target population were patients diagnosed with IBD, both from the adult and the paediatric population, treated between 2017 and 2020 at the outpatient clinics of six different institutions, which included four gastroenterology centres, one coloproctology centre, and one paediatric gastroenterology centre, in different Colombian cities.

The study population consisted of patients of any age, both adults and children, who were treated at the outpatient clinics of four Gastroadvanced IPS [Instituto Prestador de Salud (Healthcare Provider)] centres in Bogotá, GastroKids S.A.S clinic in Pereira and the Instituto de Coloproctología ICO [ICO Coloproctology Institute] in Medellín. Adults were considered to be those patients 18 years of age or older (by national legislative decree), and the paediatric population was defined as that from 2 to 17 years of age.

Eligible adult and paediatric patients were required to have complete information on year of birth, age, sex, and active clinical follow-up at each study institution. Subjects with a diagnosis of indeterminate colitis were excluded.

Data collectionFor a period of three years information was collected on different dates in the various hospitals included in the study. Medical records were used as the primary source of information. Sociodemographic and clinical variables such as sex, age, extent of IBD, age at diagnosis of IBD, pharmacological treatment for IBD and clinical response to pharmacological treatment were collected. Indications for biologic therapy, age at start of biologic therapy, IBD-related hospitalisations, frequency of extraintestinal manifestations, IBD complications, and history of surgery and type of procedure were also considered. The treatment used in each patient, frequency of requirement for corticosteroids, use of immunosuppressant (azathioprine), according to phenotype of the disease and time it was required were recorded. Requirement for biologic therapy according to first-, second- or third-line use was also considered. Biologics available in Colombia include tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (anti-TNF), infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab, and certolizumab; α4β7-integrin inhibitor, vedolizumab; interleukin-12 and interleukin-23 inhibitor, ustekinumab; and Janus kinase inhibitor, tofacitinib. Frequency was evaluated in indications of biologic therapy, and induction or maintenance therapeutic efficacy according to the drug chosen. In those patients who required biologics, therapeutic response was evaluated in clinical terms, with data collection at a single point in time, as appropriate, when completing the induction phase and in maintenance according to recommended regimens according to specific indication.

DefinitionsTo evaluate the severity of the disease, in adults and paediatric patients the Montreal classification was used12 for UC according to the extension (E1: proctitis, E2: left-sided colitis, and E3: extensive or pancolitis) and for CD, location (L1: terminal ileum, L2: colon, L3: ileocolonic, and L4: upper gastrointestinal location), and behaviour (B1: non-stricturing and non-penetrating, B2: stricturing, B3: penetrating, and p: perianal disease).

Response to drug treatment was evaluated according to clinical terms, in adults, for UC using the severity subindex according to the Montreal scale (clinical remission: no symptoms of UC; mild activity: ≤4 bloody stools per day, no fever, pulse <90bpm, haemoglobin ≥10.5g/dl (105g/l), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) <30mm/h; moderate activity: >4–5 stools per day but with minimal signs of systemic toxicity; severe activity: ≥6 bloody stools per day, pulse ≥90bpm, temperature ≥99.5°F (37.5°C), haemoglobin <10.5g/dl (105g/l), ESR >30mm/h),12 and for CD with the Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) (0–149 points: asymptomatic remission; 150–220 points: mildly to moderately active Crohn’s disease; 221–450 points: moderately to severely active disease; 451–1100 points: severely active to fulminant disease).13 In paediatric patients, for UC activity, the Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index (PUCAI) was used (0–9 points: remission; 10–34 points: mild activity; 35–64 points: moderate activity; 65–85 points: severe activity),14 and for CD the Pediatric Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (PCDAI) was used (<10 points: remission; 10–27.5 points: mild activity; 30–37.5 points: moderate activity; ≥40 points severe activity).15 Primary therapeutic failure was considered to occur in those patients who did not respond to anti-TNF induction therapy; and secondary therapeutic failure was considered to occur in those patients who initially responded to anti-TNF drugs and interruption of therapy due to loss of response (secondary non-response).16

Statistical analysisExcel version 2019 was used to prepare the database. Missing data were completed by re-reviewing the information sources and ultimately only data analyses of complete data were performed. The data processing was carried out in the program for social sciences, SPSS version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). For the descriptive analysis of the quantitative variables, the arithmetic mean, the minimum, the maximum, and the standard deviation (SD) were used; for qualitative variables, absolute and relative frequencies were used. Quantitative variables were compared according to their distribution using the Mann–Whitney U test or Student’s t test. The p values were calculated and were considered statistically significant if they were less than 0.05.

Ethical considerationsThis investigation was reviewed and approved by the participating institutions’ Research Ethics Committees. The requirements established in the Declaration of Helsinki, version 2013, in Fortaleza, Brazil, were taken into account for the investigation’s design,17 as well as resolution 8430 of 1993 of the National Ministry of Health of Colombia,18 so that it was considered to be an investigation without risk, and confidentiality and preservation of the information collected was guaranteed. Informed consent was not required to conduct the investigation. None of the records contained sensitive information about the identity of patients.

ResultsA total of 605 patients were evaluated, of whom 169 (27.9%) were from Bogotá, 396 (65.4%) from Medellín and 40 (6.6%) from a paediatric care centre in Pereira (Gastrokids S.A.S).

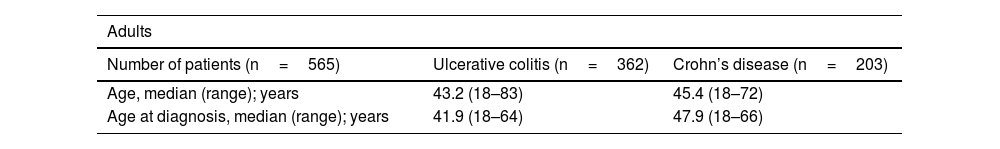

Clinical and demographic characteristicsFive hundred and sixty-five (93.4%) adults were included, predominantly women, with a mean age of 43 years (SD 12.78), a minimum age of 18 years and a maximum age of 83 years. Regarding the type of IBD, UC predominated, with a UC:CD ratio of 1.8:1 cases. A significant difference was found (p=0.02342) regarding older age at diagnosis of CD (Table 1). In the paediatric cohort (40 patients), the majority were female, and the most frequent type of IBD was UC (Table 1).

Clinical and demographic characteristics of patients with IBD.

| Adults | ||

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients (n=565) | Ulcerative colitis (n=362) | Crohn’s disease (n=203) |

| Age, median (range); years | 43.2 (18–83) | 45.4 (18–72) |

| Age at diagnosis, median (range); years | 41.9 (18–64) | 47.9 (18–66) |

| Sex | ||

|---|---|---|

| Male, n (%) | 123 (33.9) | 74 (36.4) |

| Female, n (%) | 239 (66) | 129 (63.5) |

| Paediatric | ||

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients (n=40) | Ulcerative colitis (n=36) | Crohn’s disease (n=4) |

| Age, median (range); years | 12 (2–17.8) | 15 (8.2–17.5) |

| Age at diagnosis, median (range); years | 10.6 (1.3–16.7) | 13 (9.5–17.9) |

| Sex | ||

|---|---|---|

| Male, n (%) | 4 (11.1) | 0 |

| Female, n (%) | 32 (88.9) | 4 (100) |

IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; n: number.

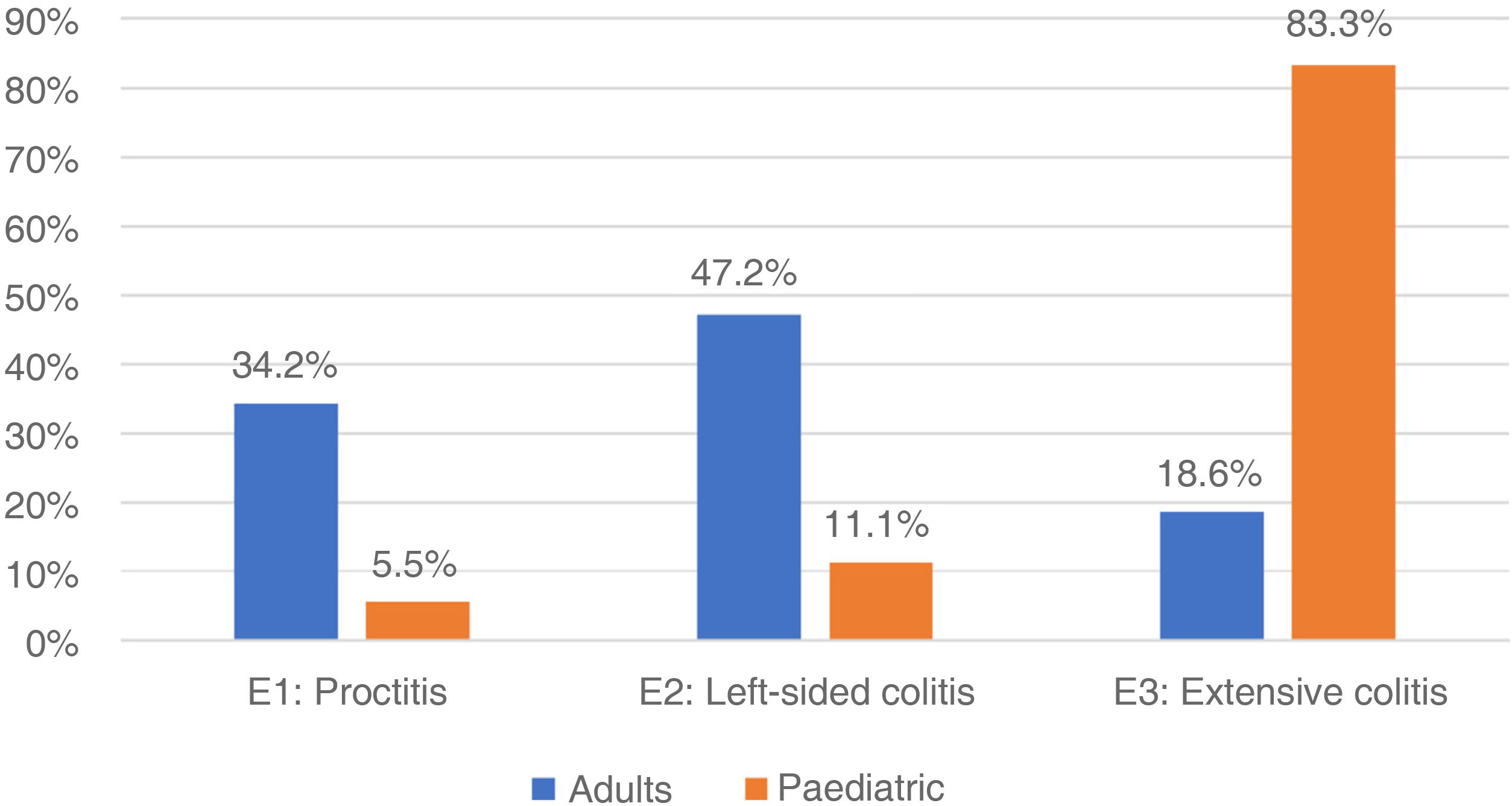

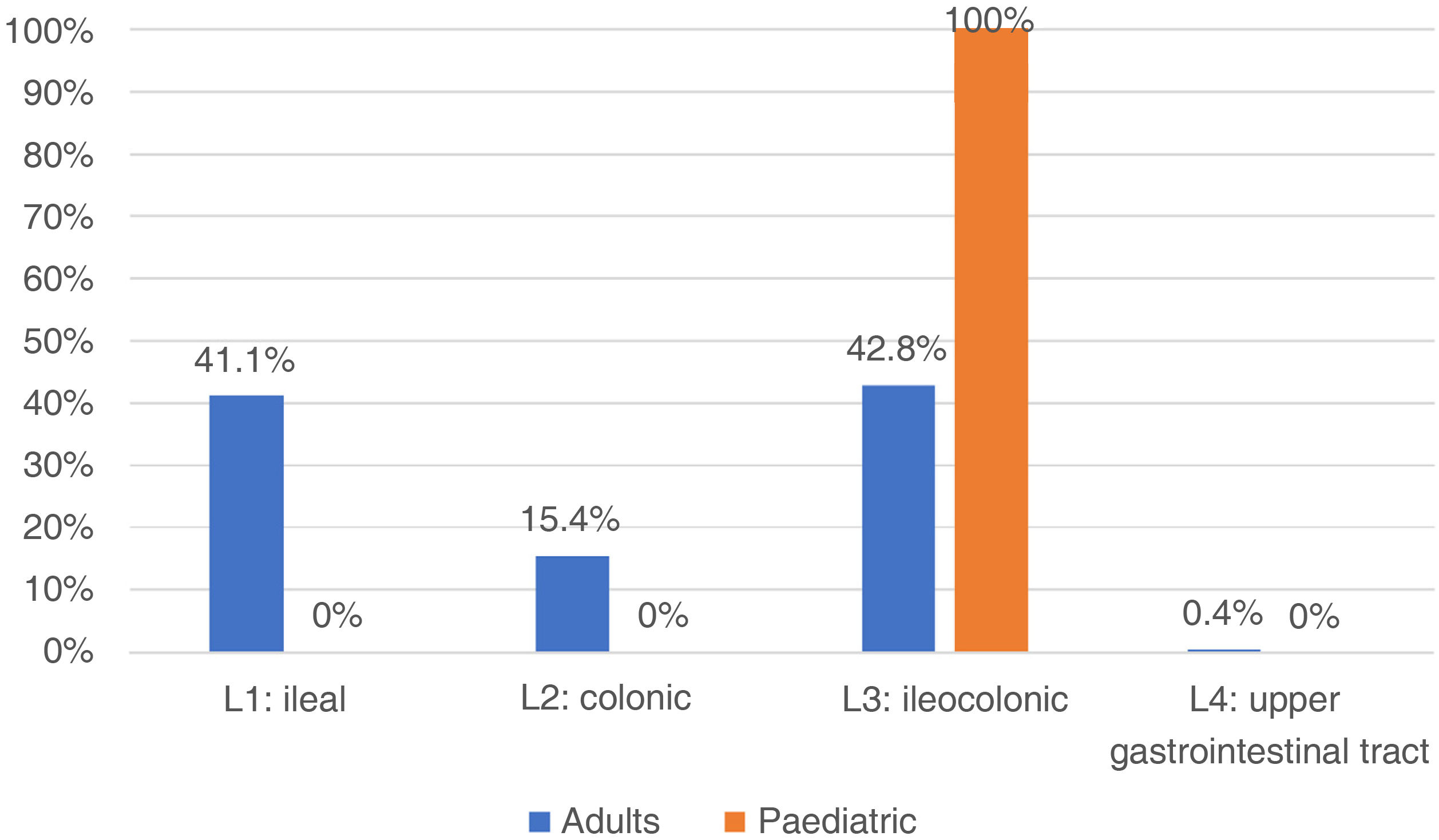

In adults, regarding the extension of the disease, the patients with UC had the greatest involvement of the left side (47.2%), followed by proctitis (34.2%) and extensive colitis (18.6%) (Fig. 1). When assessing severity, the majority had mild activity (48.9%) and 10% were in clinical remission. In those with a diagnosis of CD, the main location was at the ileocolonic level (L3) 42.8%, followed by the ileal (L1) 41.1%, colonic (L2) 15.4% and proximal (L4) with two cases (0.4%) (Fig. 2), and behaviour was mostly non-stricturing inflammatory (B1) with 51%. When assessing severity, 43.7% had mild activity and 9.2% were in clinical remission.

In the paediatric cohort, in those with UC, 30 (83.3%) presented with extensive colitis, followed by four with left-sided colitis (11.11%) and two with proctitis (5.5%) (Fig. 1). Ninety-five percent were in remission (PUCAI 0–9), 4% had mild activity (PUCAI 10–34) and 1% moderate activity (PUCAI 35–64), with no patients experiencing a severe flare-up or hospitalised. The four paediatric patients with CD presented with ileocolonic location (L3) (Fig. 2), with non-fistulising, non-stricturing inflammatory behaviour in three (75%), and one (25%) being fistulising (B3) and perianal (p). All presented with delayed growth at the time of diagnosis (stage G1). Regarding activity, all were in remission (PCDAI<10).

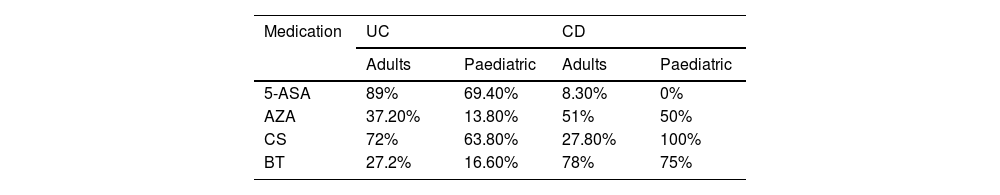

Medical treatmentWithin the medical treatment regimens (Table 1), among adults, when divided by disease, in UC, 95% required pharmacological management throughout the disease, aminosalicylates (5-ASA) was the cornerstone of treatment followed by immunosuppressants, specifically azathioprine (AZA), despite the fact that in 72.2% the use of steroids was necessary at some point in order to obtain remission; in no case did it exceed 12 weeks. In CD, 100% required pharmacological management, and when comparing CD with UC, a higher frequency of biologic use, and less use of conventional therapy was documented (Table 2).

Frequencies of use of pharmacological therapies in IBD according to disease and type of population.

| Medication | UC | CD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adults | Paediatric | Adults | Paediatric | |

| 5-ASA | 89% | 69.40% | 8.30% | 0% |

| AZA | 37.20% | 13.80% | 51% | 50% |

| CS | 72% | 63.80% | 27.80% | 100% |

| BT | 27.2% | 16.60% | 78% | 75% |

5-ASA: aminosalicylates; AZA: azathioprine; BT: biologic therapy; CD: Crohn’s disease; CS: corticosteroids; UC: ulcerative colitis.

Among paediatric patients with UC, 90% required pharmacological management throughout the disease; the frequencies of use of 5-ASA, AZA, steroids, and biologics were lower compared to adults. And in CD, 100% required pharmacological management, predominantly biologics (three infliximab and one adalimumab) and AZA (Table 1). All of these patients had required steroid use at some point in their disease. Biologic indications were no response to previous treatments in three cases (75%), and fistulising disease in one case (25%).

The biologics used in the first line were: infliximab 24.8%, adalimumab: 59%, vedolizumab: 4.0%, and golimumab: 24%. When a second line of management was required, the distribution was: infliximab 11.1%, adalimumab 44.4%, and vedolizumab 44.4%; and in those who had a third line of treatment, it was initiated with golimumab, ustekinumab, certolizumab and tofacitinib in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis and UC; all used as one per case. When evaluating the time between diagnosis and start of biologic therapy, it was 2.81 years in UC, and 5.12 years in CD, with a non-statistically significant difference p=0.08721.

Biologic therapy efficacyAmong the indications for biologic therapy were: luminal activity 78.4%, extraintestinal manifestations 13.5%, and postoperative recurrence in 8.1%. The choice of biologic medication was not affected by availability at the national level. When evaluating the efficacy of induction, there was evidence of lack of primary response in 33.3%, clinical response in 47.2% and remission in 19.4%. During maintenance, secondary failure occurred in 36.1%, response in 47.2% and remission 16.7%. During the clinical course, in the treatment biologic therapy was optimised in 18.9%.

Hospitalisation and surgeryThe overall frequency of hospitalisation was 39.5%, with no significant differences between UC and CD (p=0.7). There was only one death associated with IBD due to fulminant colitis.

Surgical procedures associated with IBD in the adult cohort were found in 37.5% in patients with UC and 62.5% with CD. All these patients required biologic therapy. No cancer frequencies were evaluated.

Among paediatric patients, the frequency of hospitalisations was low at 2.7%, and in terms of surgery, of the subjects included, only in one case was colectomy required prior to follow-up in one of the institutions in a patient with toxic megacolon initially classified as UC who was subsequently diagnosed with CD by enteroscopy, and management of perianal fistula in one of our patients with CD.

DiscussionThis study describes a Colombian cohort with IBD, the strengths of which include the number of patients from six IBD reference centres, with a wide variety of clinical phenotypes, and in which paediatric patients were included. Its findings merit analysis in light of the current evidence.

This study presents some findings similar to other studies at the national level,19,20 and in Latin America,5,7,8 finding that IBD was more common in young women. Likewise, UC was the most frequent diagnosis and the mean age at which it was diagnosed was earlier compared to that of CD. Regarding paediatric patients, the characteristics were variable compared to other population studies. On the one hand, the age at diagnosis of UC and CD was close to what was found in the EUROKIDS registry21 but diagnosis occurred later compared to what was found in other Latin American countries.22 On the other hand, females were found to be predominantly affected, which differs from other works, including studies carried out in Europe, Asia, and Latin America21–23 where it is males who are mainly affected by IBD.

In CD, both in adults and paediatrics, the duration of the disease from diagnosis to the cut-off time was longer, thus presenting older age at diagnosis, which is an unusual result compared to other studies at the regional level.8,9 Although the frequency of timely diagnosis of both UC and CD has been increasing over the last three decades in Latin America, and there is greater access to health infrastructure and technology,9,22 family or primary medical staff may be unfamiliar with the symptoms of CD. Firstly, they do not undergo training on the fact that IBD is a growing reality in our environment, and secondly, they do not consider this disease as it does not traditionally present with bloody diarrhoea but rather with chronic abdominal pain, weight loss and iron deficiency anaemia. In addition, its presentation is more indolent and less florid than UC due to its transmural involvement and ileocaecal involvement, making its assessment more difficult.24 Therefore, in future population studies, age at diagnosis and length of delay in diagnosis are variables of interest to consider regarding IBD epidemiology at the regional level.

Regarding disease phenotypes, in our cohort, in adults, in UC the involvement of the left colon (E2) was more frequent, followed by proctitis and extensive colitis, while in CD the colonic (L2) and ileocolonic location (L3) were the most frequent, and non-penetrating non-stricturing behaviour (B1), with a low frequency of perianal disease (p). All of the above is consistent with what has been published in the literature.8,9,25 It should be mentioned that, in UC, there has been a difference observed in UC extension according to age,9,10 and of those who have disease limited to the rectum or sigmoid colon (distal colitis), 25%–50% progress to more extensive forms of the disease over time26–28; in our casuistry this is a minimal phenomenon. In CD it should be noted that the B3 pattern includes all perianal disease,29 that as a separate group would account for 43% of our cohort for CD. This shows us two sides of the same coin and the fact that we are detecting and treating the majority of patients in the initial stages of the disease, but also, and with very close numbers, we have a large group with the most complicated presentations of this. In the paediatric group, the most extensive forms predominated in UC and in CD the ileocolonic location and non-fistulising, non-penetrating inflammatory behaviour predominated, and fistulising forms were observed. IBD can present in up to 30% in the paediatric age, with more severe and extensive presentations.30 These results support the notion that IBD is a heterogeneous entity, in which environmental factors such as socioeconomic status, exposure to infections, abuse of antibiotics, and poor hygiene, could help explain epidemiological differences between populations.

In IBD, therapy should be guided by the clinical presentation of the disease, its extension and severity, previous responses to treatments, and the existence of complications.31,32 In our cohort, the frequency of steroid-sparing immunosuppressant use and biologic therapy was documented in around 35% and 50% of the cases of UC and CD, respectively, which possibly had an impact on better outcomes, given that most patients they were in clinical remission or had mild activity. It is also confirmed that conventional therapy with its combinations (5-ASA, steroids, and immunomodulators) was sufficient for inflammatory control and remission maintenance in about 73% of patients with UC, while in CD it corresponded to less than one quarter. This difference has been previously described in other studies,8,33 and is related to the fact that it is more difficult to treat patients with severe CD, consistent with our reality.

Regarding biologic therapy, there was greater use in CD than UC, one third of patients were not primary responders to first-line biologic therapy, and of the primary responders, approximately one third presented with therapeutic failure or drug intolerance. Also, despite therapy with first-generation biologics, primary anti-TNF failure may occur in almost 40%, and even secondary failure in up to 46%, due to increased clearance of the drug or development of neutralising antibodies.34 The results in our study are removed from what was observed in cohort studies from the English-speaking world35 and Europe,36,37 in which a lower proportion of patients exposed to biologic therapy was observed, but with similar frequencies of therapeutic failure,35–37 and compared to these, in our study, patients presented with a higher frequency in more extensive forms of the disease, resistance and dependence on steroids, presence of extraintestinal manifestations and requirement for surgery, it being the real life experience in our setting.

Consequently, with the current epidemiological stage known as acceleration in incidence that Latin America and the Caribbean are in,4 higher rates of hospitalisation and surgery have been observed and, at the same time, greater use of resources for treating IBD activity and preventing its complications.5,7,8 Our study demonstrated that almost 40% of adults required hospitalisation, with no significant differences seen between UC and CD; while the frequency of surgery required in CD was higher than in UC. In contrast, in paediatric patients the frequency of hospitalisation and surgical requirement for IBD were low. The proportion of patients who required hospitalisation, as well as surgery, both in UC and CD, were higher than that described in other countries, including Latin America,7,8 the USA,38 Europe39,40 and Asia.41 Within Latin American countries, higher rates of hospitalisation had previously been described in Colombia compared to other countries in the same region.5,9 These findings support the idea that the characteristics of IBD vary from country to country, and between regions, supporting a multifactorial influence on IBD, and what this variation entails in the population.

There are some limitations to the study; the main one being its retrospective nature, being based on data taken on a review of medical records of patients evaluated on an outpatient basis, and the quality of the information could be affected when completing the medical records. Verification of clinical record data by at least two investigators could also reduce interviewer bias. It should also be mentioned that laboratory results (for example, complete blood counts, C-reactive protein, serum level of biologics and antibodies) are lacking, preventing deeper investigation of the association between disease progression and different treatment-related decisions. On the other hand, the different participating institutions are highly complex reference centres for IBD patients, which is why patients with more severe disease and complications than those from other centres in Colombia were probably included, and it is known that these types of patients may require more advanced management from the therapeutic point of view. Despite this, it should be mentioned that these are centres with staff trained in the use of biological therapies, more frequently using them, so the reality for Colombia is not reflected. Even though it was a purely descriptive study, with limitations in its extension and the centres included, by including subjects of all ages, it provides an overview of the characteristics of IBD in younger groups and a comparison with older age groups. The sample included in the study is also considered representative. The documented statistical data is concordant with and similar to previous information.

ConclusionsThis study provides valuable information on IBD in our setting. In summary, a predominance in the prevalence of UC and a later diagnosis of CD were demonstrated. Considerable frequency of use of immunosuppressants as a steroid-sparing agent and biologic therapy was also documented, with better disease outcomes. In CD there was a higher frequency of use of biologic therapy compared to UC. The main indication for biologic therapy was luminal activity, and all patients who underwent surgical management required biologic therapy. IBD mortality was very low. Compared to other countries, there was a higher frequency of hospitalisation and requirement for surgery.

All these results indicate that an earlier diagnosis is needed, with a better therapeutic approach, which will result in lower mortality, frequency of hospitalisation and surgery, and requirement for biological therapy.

FundingNo funding was received for this study.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Author’s contributionVPI, CFS, JSFO, MV, JK, NLE and JRM contributed to all stages of the research (literature review, data collection, and composition). All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.