High-definition virtual chromoendoscopy, along with targeted biopsies, is recommended for dysplasia surveillance in ulcerative colitis patients at risk for colorectal cancer. Computer-aided detection (CADe) systems aim to improve colonic adenoma detection, however their efficacy in detecting polyps and adenomas in this context remains unclear. This study evaluates the CADe Discovery™ system's effectiveness in detecting colonic dysplasia in ulcerative colitis patients at risk for colorectal cancer.

Patients and methodsA prospective cross-sectional, non-inferiority, diagnostic test comparison study was conducted on ulcerative colitis patients undergoing colorectal cancer surveillance colonoscopy between January 2021 and April 2021. Patients underwent virtual chromoendoscopy (VCE) with iSCAN 1 and 3 with optical enhancement. One endoscopist, blinded to CADe Discovery™ system results, examined colon sections, while a second endoscopist concurrently reviewed CADe images. Suspicious areas detected by both techniques underwent resection. Proportions of dysplastic lesions and patients with dysplasia detected by VCE or CADe were calculated.

ResultsFifty-two patients were included, and 48 lesions analyzed. VCE and CADe each detected 9 cases of dysplasia (21.4% and 20.0%, respectively; p=0.629) in 8 patients and 7 patients (15.4% vs. 13.5%, respectively; p=0.713). Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values, and diagnostic accuracy for dysplasia detection using VCE or CADe were 90% and 90%, 13% and 5%, 21% and 2%, 83% and 67%, and 29.2% and 22.9%, respectively.

ConclusionsThe CADe Discovery™ system shows similar diagnostic performance to VCE with iSCAN in detecting colonic dysplasia in ulcerative colitis patients at risk for colorectal cancer.

La cromoendoscopia virtual (CEV) de alta definición se recomienda para la vigilancia de displasias en pacientes con colitis ulcerosa y riesgo de cáncer colorrectal. Los sistemas de detección por computadora (CADe) buscan mejorar la detección de adenomas colónicos, pero su eficacia en este contexto aún no está definida. Se evalúa la eficacia del sistema CADe DiscoveryTM para detectar displasias colónicas en estos pacientes.

Pacientes y métodosEstudio prospectivo de comparación de pruebas diagnósticas de no inferioridad, transversal, en pacientes con colitis ulcerosa sometidos a colonoscopia de vigilancia entre enero de 2021 y abril de 2021. Se realizó una CEV con iSCAN 1 y 3 con realce óptico. Un endoscopista examinó el colon en secciones, mientras otro revisó las imágenes CADe. Las áreas sospechosas detectadas por ambas técnicas fueron resecadas. Se calcularon las proporciones de lesiones displásicas y de pacientes con displasia detectados por VCE o CADe.

ResultadosSe analizaron 48 lesiones en 52 pacientes. VCE y CADe detectaron 9 casos de displasia cada uno (21,4 y 20,0%, respectivamente; p=0,629) en 8 y 7 pacientes (15,4 vs. 13,5%, respectivamente; p=0,713). Sensibilidad, especificidad, valores predictivos positivo y negativo, y precisión diagnóstica para detectar displasia utilizando VCE o CADe fueron del 90 y 90%, 13 y 5%, 21 y 2%, 83 y 67%, y 29,2 y 22,9%, respectivamente.

ConclusionesEl sistema CADe DiscoveryTM muestra un rendimiento diagnóstico similar al de CEV con iSCAN en la detección de displasias colónicas en pacientes con colitis ulcerosa de riesgo de cáncer colorrectal.

Ulcerative colitis (UC) and colonic Crohn's disease are associated with an increased risk of colorectal cancer (CRC).1 Currently, 1.2% of patients with CRC have associated Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and they are, on average, 15 years younger than the general population. Furthermore, the 5-year survival rate is 14 percentage points lower in patients under the age of 65.2

Dysplasia is the immediate precursor of CRC.3 So, early dysplasia detection and correct management is crucial to prevent CRC. Population-based studies and meta-analyses have shown that endoscopic surveillance is associated to a lower risk of advanced and interval neoplasia, as well as a reduction in CRC mortality.4 Screening programs in patients with IBD are recommended to detect dysplasia not only when it is endoscopically resectable but also before it progresses to advanced CRC. For this reason, various endoscopic techniques have been described to enhance the identification of premalignant lesions in these patients. These techniques include dye-spraying chromoendoscopy (DCE) with targeted biopsies and, more recently, virtual chromoendoscopy (VCE).5–7 VCE encompasses a series of techniques that enhance both the visibility of superficial structures and the morphology of blood vessels without the use of dyes, with performance similar to DCE, while requiring less exploration time.8

In recent years, computerized artificial intelligence using deep learning systems have been developed to assist endoscopists in real-time computer-aided detection (CADe) of polyps and adenomas with high accuracy.9 Additionally, these systems have been shown to increase adenoma detection in non-IBD patients by 15%.10 Moreover, CADe systems can compensate for endoscopists’ limited experience, distractions, and even overdiagnosis of polyps. The application of these new endoscopic diagnostic systems in patients with IBD could be accompanied in the immediate future by a change in the management strategy of these patients.

The main objective of this study was to assess the efficacy of the CADe Discovery™ system, in terms of detecting colonic dysplastic lesions, in comparison to VCE with iSCAN in patients with UC at risk for CRC undergoing surveillance colonoscopy.

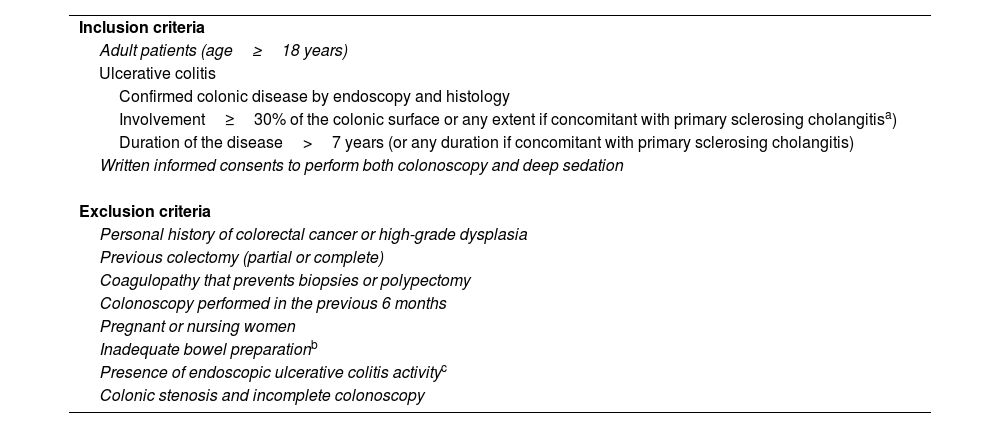

Patients and methodsThis was a single-center, cross-sectional diagnostic test comparison study that compared the CADe Discovery™ system to VCE with iSCAN for detecting dysplasia during surveillance colonoscopy in consecutive UC patients at risk for CRC, recruited according with the European Crohn's and Colitis Organization (ECCO) guidelines. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria |

| Adult patients (age≥18 years) |

| Ulcerative colitis |

| Confirmed colonic disease by endoscopy and histology |

| Involvement≥30% of the colonic surface or any extent if concomitant with primary sclerosing cholangitisa) |

| Duration of the disease>7 years (or any duration if concomitant with primary sclerosing cholangitis) |

| Written informed consents to perform both colonoscopy and deep sedation |

| Exclusion criteria |

| Personal history of colorectal cancer or high-grade dysplasia |

| Previous colectomy (partial or complete) |

| Coagulopathy that prevents biopsies or polypectomy |

| Colonoscopy performed in the previous 6 months |

| Pregnant or nursing women |

| Inadequate bowel preparationb |

| Presence of endoscopic ulcerative colitis activityc |

| Colonic stenosis and incomplete colonoscopy |

Baseline and clinical data were obtained from the electronic health records, including date of birth, sex, smoking status, age at UC diagnosis, number of flares, family history of CRC, diagnosis of primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), duration of disease in years, and history of colorectal dysplasia. In accordance with accepted risk factors for CRC, patients were stratified into groups with low, intermediate, or high risk.13 Data from previous surveillance procedures were collected from colonoscopy and pathology reports. The maximum extent of colonic disease was determined based on the historical records documented in the electronic health record and/or histologic findings. Any documented exposure to medication before and at inclusion was collected. For each endoscopic procedure, the following data were collected: date, extent of intubation, and previous features related with UC-associated dysplasia (presence of postinflammatory polyps – PIPs–, colonic strictures, scarring, or tubular appearance).14

ProceduresPatients underwent a dietary restriction of high-residue foods for 2 days before the procedure and a standard bowel preparation, which included the ingestion of 2L of a standard split-dose polyethylene glycol plus ascorbic acid solution or a magnesium citrate-based bowel preparation. The endoscopies were performed, after obtaining appropriate signed consents for both colonoscopy and sedation, under unconscious sedation controlled by an anesthesiologist. Colonoscopies were carried out or directly supervised by a dedicated endoscopist (A.L-S) with extensive experience in DCE and VCE,15–17 and assisted by an experienced nurse. High-definition endoscopes and video processors (EC390LI and Optivista EPK-i7010, respectively; Pentax, Tokyo, Japan) were used for all procedures.

White light endoscopy (WLE) was used during the advancement of the scope up to the cecum (no iSCAN processor settings were selected).18 Adequate cleaning with the water jet pump and aspiration of fecal material or mucus were performed. We did not focus on lesion detection during the colonoscope insertion.19 The success of cecum intubation was verified by identifying the usual landmarks, including the ileocecal valve, triradiate caecum folds, and the appendix orifice.

After intubating the cecum, the colon was divided into segments defined by the hepatic and splenic flexures and the rectosigmoid junction. Two endoscopists worked in parallel: Endoscopist 1 performed VCE, selecting iSCAN mode 1 (for detection of surface irregularities) and mode 3 with optical enhancement (OE) (for vascular and pattern characterization) in an on-screen double vision mode known as “twin mode” by pressing a pre-assigned button on the handpiece of the scope.20 Simultaneously, Endoscopist 2 reviewed the Discovery™ CADe images on another screen within the same endoscopic area. Discovery™ (Pentax, Tokyo, Japan) is an automated polyp CADe system developed to enhance polyp detection.21 The system was connected to the endoscopy processor to capture the colonoscopy video stream synchronously. An alert box was displayed on the monitor that played when the system detected a polyp (simultaneous audible alarms were turned off). Both endoscopists were initially blinded to the findings on the other screen during the exploration. At the end of each colonic segment, the endoscopists shared the information provided by each screen. No random biopsies were performed on any patient. The exploration time was recorded (the resection time was not excluded).

Description of endoscopic findingsThe morphology, size, and location of any visible focal lesion were recorded in each group, considering the location, size, and morphology (using the Paris and the Kudo pit pattern classifications).22,23 Only suspicious areas were resected for further analysis. Suspicious areas were defined as any mucosal irregularity that was not entirely secondary to chronic or active UC.24 Specifically, typical postinflammatory polyps, flat areas with a hyperplastic appearance located in the distal sigmoid and/or rectum, and benign-appearing luminal strictures were not considered suspicious areas. Lesions smaller than 5mm were resected using biopsy forceps or a polypectomy snare, based on the endoscopist's criteria. Polyps 5mm or larger were removed using a polypectomy snare. Protruding non-pedunculated polyps and flat lesions 5mm or larger were excised using the endoscopic mucosal resection technique.

The colonic location of PIPs was identified, and the patients were subclassified as having few or many PIPs if they were described as sporadic or distributed throughout the colon, respectively.25

Histopathological assessmentThe histological diagnosis from all biopsy samples served as the reference standard for each patient. Biopsy samples underwent standard processing and staining procedures, followed by evaluation in accordance with the Vienna criteria for gastrointestinal neoplasia by an experienced gastrointestinal pathologist.13,26 Lesions were categorized into two groups: (1) Dysplasia, which encompassed low-grade dysplasia, high grade dysplasia, invasive carcinoma, and sessile serrated adenomas with dysplasia; and (2) Non-dysplasia, which included hyperplastic polyps, sessile serrated polyps without dysplasia, PIP, scarring tissue, and other nonspecific non-neoplastic mucosal changes. Specimens showing signs of dysplasia were independently reviewed by a second pathologist, and in cases of disagreement between observers, a consensus was reached.

OutcomesThe histological outcome after the procedure was used as a reference standard diagnosis for each patient. The primary outcomes included calculating both the proportion of dysplastic lesions in relation to the total number of analyzed lesions detected by VCE or CADe and the proportion of patients with dysplastic lesions in relation to all the patients with UC at risk for CRC undergoing surveillance colonoscopy. Secondary outcomes were to calculate the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), diagnostic accuracy and the nonparametric area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and its 95% confidence interval (95%CI) of the VCE and CADe to detect the presence of dysplasia.

Sample sizeBased on a previous study conducted by our group,15 we assumed a 15% risk of colonic dysplasia in the specific population and a 15% detection rate for all dysplastic lesions. The study was designed as a non-inferiority trial with an effect size of 0.5. This required a sample size of 51 patients to achieve an alpha error of 0.05 with a statistical power of 0.80 (beta error of 0.20). Taking these considerations into account, it can be note that in this study, a non-inferiority margin of 17% has been considered (https://www.sealedenvelope.com/power/binary-noninferior/).

Statistical analysisQuantitative variables are expressed as medians and interquartile ranges or means and standard deviations (SD). Categorical variables are expressed as absolute frequency and percentages of the subgroups. Comparisons were made between the CADe group and the VCE group. The proportion of dysplastic lesions in relation to the total number of analyzed lesions (referred to as the ‘per lesion’ dysplasia detection rate – DDR–), and the proportion of patients with dysplasia in relation to the total number of patients included in the study (referred to as the ‘per patient’ DDR) were calculated. Before conducting parametric tests, normal distribution of the continuous variables was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Differences in continuous parametric variables were evaluated using Student's t-test. Categorical data were compared using Chi-square test and Fisher's exact test (when the expected frequency in cells was <5). All test were two-sided, and p values<0.05 were considered statistically significant. To describe outcomes and differences, confidence intervals have also been presented. These intervals, along with the non-inferiority margin that has also been highlighted, will help to assess the statistical significance of the results. The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV and diagnostic accuracy, along with their corresponding confidence intervals (CI), were computed using R package version 4.3.2 (R Core Team 2021). All other calculations were made using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26.0 (IBM, Somers, New York, USA).

Ethical considerationsThe study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of our institution (identification number: 62/21) and registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT05171634). All patients provided written informed consent to participate in the research. All procedures conducted in studies involving human participants adhered to ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and were in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments or comparable ethical standards.

ResultsPatient demographics and colonoscopy findingsBetween January 2021 and April 2021, 58 consecutive patients with UC at risk for CRC were referred to our Endoscopy unit for surveillance colonoscopy. Overall, six patients were excluded according to the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. The study flow chart is represented in Fig. 1. Ultimately, 52 patients were enrolled in the study. The detailed clinical and demographic characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of patients in 52 patients at inclusion into the study.

| Male sex, n (%) | 30 (57.7) |

| Age at index colonoscopy (yrs.), median (IQR) | 54 (48–63) |

| Smoking: active/previous/no | 7/16/29 |

| Ulcerative colitis extension | |

| Pancolitis, n (%) | 24 (46.2) |

| Left-sided colitis, n (%) | 28 (53.8) |

| Age at disease onset (yrs.), median (IQR) | 37 (29–49) |

| Duration of disease (yrs.), median (IQR) | 13 (9–23) |

| Family history of colorectal cancer, n (%) | 14 (27) |

| Personal history of colorectal dysplasia, n (%) | 12 (23.1) |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis, n (%) | 2 (3.8) |

| Risk group for colorectal cancer,an (%) | |

| High risk | 15 (28.8) |

| Moderate risk | 18 (34.6) |

| Low risk | 19 (36.5) |

| Extraintestinal manifestations, n (%) | 7 (13.5) |

| Flares previous to inclusion, median (IQR) | 2 (1–4) |

| Treatment at index colonoscopy, n (%) | |

| Salicylates | 35 (67.3) |

| Immunomodulators | 8 (15.4) |

| Biologics | 7 (13.5) |

| Combined treatmentb | 1 (1.9) |

| No treatment | 1 (1.9) |

| Previous colonoscopy surveillance details in 37 patients | |

| Procedures per patient, median (IQR) | 1 (1–2) |

| HD-WLE with random biopsies, n (%)c | 16 (43.2) |

| DCE with targeted-biopsies, n (%)c | 9 (24.3) |

| VCE with targeted-biopsies, n (%)c | 12 (32.4) |

HD-WLE, high-definition white light endoscopy; DCE, dye-spraying chromoendoscopy (with indigo carmine); VCE, virtual chromoendoscopy (with iSCAN); IQR, interquartile range.

Group of risk: high (stricture within the past 5 years, dysplasia within the past 5 years, Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis, colorectal cancer in a first-degree relative younger than 50 years); moderate (post-inflammatory polyps, colorectal cancer in a first-degree older than 50 years, extensive colitis with moderate or severe endoscopic or histological inflammation); low (colitis affecting less than 50% of the colon surface area and/or extensive colitis with mild endoscopic or histological inflammation).13

The colonic findings are presented in Table 3. A total of 61 suspicious areas underwent resection, predominantly localized in the rectum and left colon (67.3%). Three of them were located in non-colitic areas. Among these, 53 were identified using VCE, while CADe detected 57 (86.9% [95%CI=77.0–96.1%] vs. 93.4% [95%CI=86.6–100%]; p=0.421). This implies that a total of 12 lesions (19.7%) remained undetected by either technique, with 8 (13.1%) exclusively identified by CADe and 4 (6.5%) solely recognized by VCE.

Characteristics of the endoscopic findings and exploration time.

| Tubular appearance,n(%) | 9 (17.3) |

| Stenosis,n(%) | 3 (5.8) |

| Scarring,n(%) | 11 (21.1) |

| Postinflammatory polyps,n(%) | 16 (30.7) |

| Many,25n (%) | 13 (25.0) |

| Localization, n (%)a | |

| Left colon | 9 (69.2) |

| Diffuse | 4 (30.8) |

| Patients with resections,n(%) | 32 (61.5) |

| Lesions resected,n | 61 |

| Localization, n | |

| Rectum | 14 |

| Left colon | 27 |

| Transverse colon | 8 |

| Right colon | 12 |

| Resections per patient, median (IQR) | 1 (0–2) |

| Size lesion (mm), mean (SD) | 4.0 (4.0) |

| Paris classification,22n | |

| 0-Ip | 1 |

| 0-Is | 52 |

| 0-IIa | 6 |

| 0-IIb | 1 |

| 0-IIc | 1 |

| Kudo pit pattern,23n | |

| I | 22 |

| II | 32 |

| IIIL | 6 |

| IIIS | 1 |

| Insertion time (min), median (IQR) | 8 (5–10) |

| Withdrawal time (min), median (IQR) | 13 (11–19) |

| Total procedure time (min), median (IQR) | 22 (16–28) |

IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation.

Thirteen (21.3%) lesions did not undergo histological analysis because they were lost after resection, all of them measuring less than 3mm in diameter and exhibiting Kudo pit pattern type I. The distribution of missed lesions was comparable between both groups. Out of the 13 lesions missed, 11 were detected by VCE and 12 by CADe. Consequently, a total of 48 lesions underwent histological analysis.

Ten dysplastic lesions were identified in 8 (15.4%) patients. The proportion of dysplastic and non-dysplastic lesions detected by VCE or CADe was comparable. However, CADe detected dysplastic lesions in 8 patients, while VCE detected them in only 7 patients. Nevertheless, the proportion of patients with or without dysplasia was similar (see Table 4). Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and diagnostic accuracy for the endoscopic diagnosis of dysplasia using VCE vs CADe were 90% (95%CI=71–100%) vs 90% (95%CI=71–100%), 13% (95%CI=2–24%) vs 5% (95%CI=0–12%), 21% (95%CI=9–34%) vs 2% (95%CI=8–32%), 83% (95%CI=54–100%) vs 67% (95%CI=54–100%), and 29.2% vs 22.9%, respectively. Corresponding values of the areas under the ROC curve (95%CI) were 0.516 (0.316–0.716) for VCE, and 0.476 (0.269–0.684) for CADe.

Distribution of lesions (‘per lesion’ analysis) and distribution of patients (‘per patient’ analysis) in relation to the presence or absence of dysplasia and the type of procedure.

| Characteristic | VCE group | CADe group |

|---|---|---|

| ‘Per lesion’ analysisa,* | ||

| Dysplastic lesions, n (%) | 9 (21.4) | 9 (20.0) |

| Low grade dysplasia | 9 | 9 |

| Non-dysplastic lesions, n (%) | 33 (78.6) | 36 (80.0) |

| Hyperplastic polyp | 14 | 16 |

| Postinflammatory polyp | 9 | 9 |

| Normal | 6 | 7 |

| Unspecific | 4 | 4 |

| ‘Per patient’ analysisb,** | ||

| Patients with dysplasia, n (%) | 8 (15.4) | 7 (13.5) |

| Patients without dysplasia, n (%) | 44 (84.6) | 45 (86.5) |

VCE, virtual chromoendoscopy (with iSCAN); CADe, computer-aided colonoscopy.

The mean (SD) size of dysplastic and non-dysplastic lesions was 6.0 (6.8) and 4.0 (3.6) millimeters, respectively (p=0.319). The dysplastic lesions were at low risk for carcinoma, and all were successfully resected during the index colonoscopy. The proportion of dysplastic lesions was higher in the right colon than in the left colon (70.0% vs. 30.0%; p=0.032). Only one dysplastic lesion, 6mm in size, was located in a non-colitic area in a patient with left-sided UC.

The presence of colonic PIPs was not related to the appearance of dysplastic lesions (OR=1.01, 95%CI=0.22–3.16; p=0.872). Concerning the endoscopic prediction of dysplasia, most of the lesions analyzed had a Kudo pit pattern type I or II (41; 85.4%); concordantly, almost all (39; 95.1%) were non-dysplastic. Examples of dysplastic colonic polyps detected by VCE and CADe are shown in Fig. 2. In Table 5, the primary characteristics of the 9 suspicious lesions, which were referred for histological analysis but remained undetected by either of the two techniques, are delineated.

Characteristics of suspicious resected lesions referred for histological analysis and not detected by VCE or CADe.

| Detection method | Lesion | Histology | Location | Size (mm) | Paris classification21 | Kudo pit pattern22 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VCE | ||||||

| 1 | Low-grade dysplasia | RC | 3 | Is | II | |

| 2 | PIP | RC | 2 | Is | II | |

| 3 | Normal | Rectum | 20 | IIa | II | |

| CADe | ||||||

| 4 | Low-grade dysplasia | TC | 3 | IIa | II | |

| 5 | Hyperplastic polyp | TC | 6 | Is | II | |

| 6 | Hyperplastic polyp | LC | 2 | IIa | I | |

| 7 | PIP | LC | 2 | Is | I | |

| 8 | Normal | Rectum | 3 | Is | II | |

| 9 | Normal | Rectum | 4 | Is | II | |

VCE, virtual chromoendoscopy (with iSCAN); CADe, computer-aided colonoscopy; PIP, postinflammatory polyp; RC, right colon; TC, transverse colon; LC, left colon.

This cross-sectional diagnostic test comparison study, which included 52 patients with UC at risk for CRC in remission, did not reveal a significant difference in the detection of colonic dysplasia between VCE with iSCAN and CADe with the Discovery™ system. Furthermore, the low prevalence of colonic dysplasia in these patients is confirmed, in accordance with the decreased relative risk of CRC in UC patients that has been demonstrated over the last few decades.27

To our knowledge, this is the first study comparing VCE to a CADe system for the detection of adenomas in patients with UC. A recent meta-analysis conducted by Shah et al., involving 14 randomized clinical trials and 10.928 patients, demonstrated a significant increase in the detection of adenomas and polyps when CADe was incorporated into colonoscopies.28 Unfortunately, none of the included studies involved patients with IBD.

The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy has endorsed the use of VCE, in addition to DCE, as a surveillance technique in patients with IBD at risk for CRC because there is insufficient evidence to recommend against the use of VCE.5 This recommendation was also recently endorsed by the American Gastroenterological Association and the European Crohn's and Colitis Organization.6,7 We demonstrated that VCE using iSCAN mode 1–3 exhibits a similar diagnostic performance to conventional DCE in the detection of colonic dysplasia in these patients.16 Furthermore, VCE emerged as a surveillance alternative that required less procedure time than DCE. Similar to our study, in a prospective randomized study, Gonzalez-Bernardo et al. found no difference between DCE and VCE using iSCAN mode 1.29 This led us to hypothesize that the use of advanced optical endoscopes may be more critical than the specific optical method applied to identify dysplastic lesions in these patients.17

Of the suspicious lesions that underwent resection, three were localized in non-colitic areas, with only one displaying dysplasia. Prior studies in UC exclude lesions found in non-colitic areas from analysis, categorizing them as sporadic adenomas.24,29 However, certain UC patients may have previously experienced extensive undiagnosed involvement due to various factors, such as incomplete initial assessment from incomplete colonoscopy, failure to adhere to recommendations for biopsying all segments to exclude microscopic involvement,7 or even subsequent unnoticed disease extension. Hence, we have not omitted this possibility when analyzing the lesions detected in follow-up colonoscopies.

Analogous to studies performed in patients without IBD,30 the results also showed significant detection of diminutive hyperplastic polyps, which may lead to unnecessary additional polypectomies. On the contrary, Ashktorab et al. showed that inflammatory polyps were more common than hyperplastic ones in IBD patients.31 In any case, the correct characterization of detected lesions is crucial for making the right decisions. Although the use of classification systems to support optical diagnosis with advanced endoscopic imaging in the lower gastrointestinal tract is recommended,32 it is not common in IBD management.5 In addition, clinical judgment alone, even in experienced endoscopists, has proven insufficient for optical diagnosis in IBD.33 In our study, a trend toward detecting more irrelevant lesions by the CADe system was observed, albeit without significant differences compared to VCE. Consequently, the occurrence of false positives, lesions identified as dysplastic but not actual, can lead to unnecessary interventions.

We usually use the Kudo pit pattern classification to predict histology during colonoscopies, which has high accuracy in patients without colitis.34 However, its precision is lower in IBD patients.35 Recently, Cassinotti et al.36 have developed a new modified Kudo classification adapted for IBD patients that aimed of improving precision, and their results are promising, although further studies are required to confirm its diagnostic yield. On the other hand, similar to other studies in IBD patients using the Paris classification to describe de endoscopic morphology of the lesions,15 the most frequent morphology in our series was 0-Is, although its accuracy in predicting dysplasia is controversial.37

Due to the decreased mortality rate an incidence of CRC in recent decades, primarily as a result of CRC screening and the removal of adenomatous polyps, advances such as automated colon polyp detection have become an attractive research topic over the past years to improve the quality of colonoscopy, in addition to detecting predominantly small polyps.38 Moreover, these systems can reduce factors such as operator fatigue, distraction, and exploration time when routinely applied. Artificial intelligence, particularly novel deep learning techniques such as CADe systems, has been developed to assists endoscopists in identifying polyps during colonoscopies in the general population. CADe has been demonstrated to increase the detection of adenomas of both flat and polypoid morphology.39 However, to the best of our knowledge, current technology still does not show sufficient diagnostic performance to be considered for clinical application in patients with colonic IBD. In our study, one patient had a dysplasia that was not detected by the CADe system. In the addition, in the “per lesion” analysis, one dysplasia was non detected by each technology, VCA and CADe. False negatives, where dysplastic lesions go unnoticed, pose a significant risk of missed therapeutic opportunity. False negatives may instill a false sense of security for both the patient and the physician, potentially leading to inadequate follow-up or decreased surveillance in the future. As a consequence, the failure of an AI system applied in colonoscopy to detect dysplastic changes in the colon mucosa can potentially lead to the progression to CRC. So, there is a need to enhance detection strategies and develop technologies to minimize this risk in these patients. Recently, the CADe system was trained with images from polypoid lesions in IBD patients to increase the accuracy to detect dysplastic polyps.40 Future studies are focused not only on polyp detection but also on other applications such as optical diagnosis (CADx), to predict pathology in real-time colonoscopies, allowing for a ‘resect and discard’ strategy, which could be a cost-effective solution in the future by improving quality of endoscopy and reducing of unnecessary polypectomies.41,42

More than 60% of the patients included in the study were at moderate to high risk of CRC (see Table 2). Among other reasons, improved surveillance strategies could explain the decreased incidence of CRC among patients with IBD.43 We routinely and consistently conduct rigorous monitoring of these patients to ensure proper compliance with the recommendations for colon dysplasia screening. This fact could account for the high number of patients included with a history of dysplasia. Recent ECCO guidelines suggest random biopsies in high-risk patients with a history of dysplasia and PSC to increase the detection of dysplasia, although no statement has been made from this question.7 When designing this study, we followed the recommendations of the 2019 ESGE Guidelines.5 According to these recommendations, for high-risk patients, chromoendoscopy with targeted biopsies could be combined with non-targeted biopsies, albeit with a weak recommendation and low-quality evidence. Our group has been including patients with IBD in CRC screening programs for over a decade in a very rigorous manner, always performing chromoendoscopy with targeted biopsies. Up to the present moment, we have not detected dysplasia or CRC in any patient with PSC during routine annual follow-up, so we have not changed this strategy when designing this study.

This study has several limitations. First, no high-grade dysplasia or carcinoma was detected during the study. Although this aspect may indicate the need to include a larger number of patients in future studies, this pattern aligns with the findings of the majority of prospective studies investigating neoplasia detection via endoscopy in patients with IBD.16,24,29,44 High-grade dysplasia tends to be observed more commonly in retrospective studies involving a larger cohort of patients,45 and in surgical specimens from IBD patients who have undergone colon stenosis surgery.3 Notably, 98.1% of our study cohort were receiving chronic pharmacological aimed at controlling inflammation. This factor may potentially contribute to a decreased progression from underlying dysplasia to high-grade dysplasia; however, a larger sample size would be necessary to draw definitive conclusions in this regard.44 Collectively, these factors account for the absence of high-grade dysplasia detection in our study. Additionally, it is characteristic in this setting to detect CRC in patients with UC who were not previously included in endoscopic screening programs. Second, all the examinations were performed or directly supervised by a senior endoscopist. This could potentially lead to an underestimation of the effectiveness of the CADe system by possibly increasing the endoscopic detection of adenomas. Third, the study and the interpretation of its findings are limited by the non-randomized, single-center design. For an unbiased analysis of the performance of a CADe system for the detection of lesions, a randomized trial design is highly warranted. Specifically, the fact that the two observing endoscopists (one for the CADe monitor and the other for observing the normal monitor) were in the same room during the procedure could potentially introduce bias that may influence the results, although this fact was taken into consideration during the study's execution to ensure it did not occur at any point. Fourth, the fact that the first endoscopist actively applied the VCE technique could be associated with a higher likehood of detecting lesions with this technique compared to the passive CADe technique controlled by the second endoscopist. Consequently, a bias in lesion detection between both techniques could have been generated. Fifth, 21.3% of the lesions detected in the study, all of them 1–2mm in diameter, could not be retrieved for histological examination. After being resected with a cold snare, these lesions were not retained in the plastic polyp trap system, which acts as a sieve installed in-line between the endoscope channel and the suction system, likely due to their small size. This issue could have been avoided by using biopsy forceps for facilitate their retrieval and should be taken into account for future studies. In a previous study by our group, which included 191 patients with IBD undergoing surveillance colonoscopy, the majority of these small lesions were removed using biopsy forceps, leading to a lesion loss ratio of only 3.3%.16 Finally, differences in exploration time between techniques were not studied due to the study's design. In our experience, as in other studies investigating the detection of CRC in the average-risk population, exploration time is not extended except in those examinations where a greater number of lesions are detected.

In conclusion, the CADe Discovery™ system demonstrates diagnostic performance similar to VCE with iSCAN in the detection of colonic dysplasia in UC patients at risk for CRC. Further studies are needed to definitively establish CADe as a viable alternative to VCE or DCE in these patients.

Author's contributionsAL-S and JMP made substantial contributions to the concept, design and interpretation of the data in the study and drafted the article; AVC, JRLM, AAG, PLA and PPV made substantial contributions to acquisition of data; PLA and JMP made substantial contributions to recruitment; FJSG and AL-S were in charge of the analysis, the interpretation of data, and the statistical analysis. All authors critically revised and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethical considerationsThe study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of our institution (identification number: 62/21) and registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT05171634). All patients provided written informed consent to participate in the research. All procedures conducted in studies involving human participants adhered to ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and were in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Data availability statementThe data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Funding statementThe current research has not received specific assistance from public sector agencies, commercial sector, or non-profit entities.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

The authors acknowledge with appreciation Jaime Hervás, Carmen García and María C. Asencio (Gastroenterology Department, Dr Peset University Hospital, Valencia, Spain) for their support to recruitment and acquisition of data; and Ian O’Leary for language assistance.

![Examples of dysplastic colonic polyps detected in a patient with ulcerative colitis using both virtual chromoendoscopy with iSCAN ‘tween mode’ [mode 1 in (a) and mode 3 with optical enhancement (OE) in (b)] and the real-time computer-aided detection Discovery™ system (c, d). Examples of dysplastic colonic polyps detected in a patient with ulcerative colitis using both virtual chromoendoscopy with iSCAN ‘tween mode’ [mode 1 in (a) and mode 3 with optical enhancement (OE) in (b)] and the real-time computer-aided detection Discovery™ system (c, d).](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/02105705/0000004800000002/v2_202502060852/S0210570524001687/v2_202502060852/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr2.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)