Neurodevelopmental and clinical problems in childhood often precede adult Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders.

We investigated if children attending a psychiatric clinic presented more psychopathology and cognitive and motor alterations if there was a family history of Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorder diagnosis. We also searched if there was a relationship between borderline/clinical scores (≥65) in Child Behavior Checklist (subscale Thought Problems) and increased problems in motor and cognitive performance.

MethodsSeventy-five children (aged 7 to 16; mean 12 y/o; 53% males) were recruited (45 reported family history -seven of them first degree-). They completed the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC-V), Movement Assessment Battery for Children (MABC-2), social cognition from the Developmental NEuroPSYchological Assessment (NEPSY-II) and Conners Continuous Performance Test (CPT-3). Parents completed the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) and Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF-2).

ResultsA neurodevelopmental disorder was the primary diagnosis in 65% (mainly ADHD). Motor performance and emotion recognition were below expected by age, and IQ was average. No relevant differences in relation to family history were found. Patients with high scores (≥65) in the CBCL Thought Problems subscale (n = 38) were older, more often presented a diagnosis of combined ADHD, performed worse in Emotion Recognition (and more often made “angry” errors), had Executive Function problems and clinical symptoms in subscales Anxious/Depressed, Withdrawal/Depressed and Attention problems.

ConclusionsIn children attending a psychiatric clinic, elevated scores on CBCL Thought Problems subscale associates with more urban upbringing, more internalizing clinical problems, executive function, and facial emotion recognition difficulties, with a tendency to report “angry” to other emotions.

In schizophrenia, or at least a subgroup of patients with this disorder, longitudinal studies show that neurodevelopmental abnormalities1 and social, emotional and behavioral problems in childhood precede the illness in early adult life.2,3

The Family High Risk (FHR-SZ) approach, in which offspring of patients are examined, and the Clinical High Risk (CHR-SZ), which targets identification of the prodrome of psychosis, are the two main paradigms to investigate deficits before the onset of the illness. However, both methods recruit a substantial proportion of “false positives” and in order to be more accurate it has been suggested that combining FHR-SZ and CHR-SZ could be important.4

Family High Risk (FHR-SZ) studies aim to determine whether, prior to a prodromal clinical picture, specific features of development are predictive of later psychosis. Early differences in motor,5–7 cognitive,4,8,9 executive function,10 and social behavior11 might reflect a stable deficit from childhood through adolescence.12 These abnormalities are not found in children who later develop bipolar disorder13 or do not seem as strong and extensive.14 Many FHR-SZ studies have excluded children meeting criteria for any childhood psychiatric disorder,12 while others find an elevated risk for ADHD and disruptive disorders.15 Also, childhood-onset disorders have been found to be prevalent in putatively prodromal adolescents16 and in adults with schizophreniform disorder.17

In terms of clinical symptoms, both childhood Internalizing and Externalizing problematic behaviors (measured with the Child Behavior Checklist -CBCL-) predicted prodromal symptoms in FHR-SZ subjects.18 And specific CBCL subscales (Social, Attention and Thought Problems) were the strongest discriminator among those who screened positive for non-affective psychosis at age 21.19,20 Hamasaki21 assessed adults with schizophrenia retrospectively and found elevated scores in similar subscales during childhood (Withdrawn, Thought Problems and Lack of Aggressive Behavior).

In this regard, CBCL has been considered useful for identifying clinically concerning psychosis in children and adolescents22,23 or comparable to Prodromal Questionnaire (Q-16) as a first-step screener in the detection of CHR-SZ adolescents.24 Salcedo22 established a T-score of 68.5 in Thought problems subscale as an optimal psychosis screening cut-off value, maximizing sensitivity and specificity. De Jong24 found that a T-score of 67 reached good sensitivity (≥80) with a permissible moderate specificity, and argued that a higher number of false positives are admissible as the next step is merely an interview, not an invasive procedure.

In the field of clinical high-risk state for psychosis (CHR-SZ), it has been highlighted that Child and Adolescent Mental Health practitioners have an important role in redefining criteria that take into account the specificity of child development.25 Defining a motor phenotype7,26 and social cognitive impairments27,28 as premorbid markers in youth could be relevant.

In this study, we recruited two groups of children and adolescents attending a psychiatric clinic, one of them with at least a first or second-degree family member with a Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorder (FHR-SZ) diagnosis and another with neither family history of schizophrenia nor bipolar disorder (non-FHR-SZ). We performed an evaluation of motor coordination, social cognition, general IQ, and sustained attention, and obtained parents’ report of current clinical symptoms and executive function.

We expect to find a theoretically more vulnerable group with marked neurodevelopmental deviations among those with family history of schizophrenia and Thought Problems in the at risk/clinical range (≥65).

Material and methodsParticipantsInclusion criteria were children aged 7 to 16 years remitted to a Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (CAMHS) by a pediatrician in Valladolid (catchment area population of 520,000). We selected an initial sample of patients who reported family history of schizophrenia spectrum disorders (first or second-degree) and another sample with neither family history of schizophrenia spectrum disorders nor bipolar disorder.

Family history of psychosis was attained by asking parents or main caretaker. Clinical diagnoses were informed by psychiatrist in charge.

Exclusion criteria consisted of significant head injury, current or past substance use, neurological disorder, intellectual disability (IQ<70), or lifetime history of psychosis.

ProcedureParents were asked for demographic information and Hollingshead Four-Factor Index of Socioeconomic Status (SES-Child) score was calculated. They also completed the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) with current symptoms and the parent report of the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function, Second Edition (BRIEF-2). Every child completed the Conners Continuous Performance Test 3rd Edition (CPT-3), Movement Assessment Battery for Children- Second Edition (MABC-2), social cognition tests from the Developmental NEuroPSYchological Assessment (NEPSY-II) and the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC-V).

CBCL (from Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment -ASEBA-) is a widely used instrument to assess psychopathology completely and accurately in children and adolescents, which is filled out by parents. The checklist consists of 113 self-administered questions, scored on a three-point scale. The time frame for item responses is the previous six months. The CBCL/6-18 is used with children between the ages of 6 and 18 and is made up of eight syndrome scales: anxious/depressed, withdrawal/depressed, somatic complaints, social problems, thought problems, attention problems, rule-breaking behavior, and aggressive behavior. These group into two higher order factors, internalizing and externalizing. The CBCL scale scores offer a T-score based on age and sex norms (≥65 borderline and ≥69 pathological), has been translated into Spanish and validated in populations in Spain.29

BRIEF-2 Parent Form is the rating scale of executive function developed for parents of children aged 5 to 18 years old which assess executive function behaviors in the home environment, obtaining three broader indexes (Behavior Regulation Index, Emotion Regulation Index, and Cognitive Regulation Index), and an overall score (Global Executive Composite). Clinically significant problems are defined by a T-score above 70 and potentially clinical by 65–69 range. This instrument has been translated and validated in Spain.30

The Conners CPT-3 assesses attention-related problems in individuals aged 8 years and older. During the 14-minute, 360-trial administration, subjects are required to respond when any letter appears, except the non-target letter “X”. Different T-scores are obtained. Detectability (d’) is a measure of how well the respondent discriminates non-targets from targets. A higher score indicates worse performance (T-score above 60 is elevated). Normative data consists of 1400 cases representative of the United States population census.31

MABC-2 is an individually administered standardized test, well established as a research tool, designed to identify, and describe impairments in motor performance in children and adolescents from 3 to 16 years of age. It comprises three subdomains: manual dexterity (measures abilities requiring fine motor skills), aiming and catching (measures throwing and catching using a tennis ball), and balance (measures static and dynamic balance). Scores are expressed as scaled scores and percentiles. This instrument has been validated in Spain.32

NEPSY-II is a comprehensive instrument designed to assess neuropsychological development. Subtests in the Social Perception domain are designed for children between 3 and 16 years of age and assess three areas: Emotion recognition (ER) (the ability to determine if two different children demonstrate the same affect and to match different children with the same affect), affect in relation to contextual cues, and theory of mind (ToM) (the ability to comprehend the perceptions and experiences of others and apply that knowledge to questions). Scores are expressed as scaled scores for ER and percentiles for ToM. This battery has been validated in Spain.33

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Clinical Hospital of Valladolid and written informed consent from parents/main caretakers and children were obtained.

Statistical analysesNormality test (Shapiro-Wilk) was done to determine normal distribution of variables with a p-value ≤ 0,05. Independent sample T-tests were done for continuous and normally distributed variables and non-parametric test (U Mann-Whitney) for continuous non-normally distributed variables. Chi-square test was used for categorical variables.

Firstly, comparisons were made between groups with and without family history of schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

Secondly, the whole sample was divided by means of the presence or absence of a borderline/clinically significant score in the Thought Problems and comparisons between other clinical and neuropsychological variables were made.

We used Bonferroni multiple correction test and assumed a p value ≤ 0,001 as statistically significant.

ResultsCharacteristics of the sampleSeventy-five patients were recruited for the study. Forty-five reported family history of schizophrenia spectrum disorders (FHR-SZ). Thirty-eight had a second-degree relative affected, four patients had a first-degree and three had both a first and a second-degree family member affected. Three FHR-SZ patients also had a second-degree relative diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

Age range was seven to sixteen years old (Mean=12.2, SD=2.5; Median=13, IQR=4) and 53.3% were males. Seventy-three percent lived in urban areas. Hollingshead Social Status ranged from 8 to 58 (Mean=35, SD=13.6; Median=35, IQR=25).

A neurodevelopmental disorder was the main diagnosis for 65.3% of the sample (32% combined ADHD, 14.7% attention deficit disorder, 5.3% learning disorder, 4% autism spectrum disorder, 4% neurodevelopmental disorder NOS, 4% ADHD NOS, 1.3% communication disorder). Adjustment disorders was the second most frequent diagnosis (9.3%) followed by depressive disorders (8%) and anxiety disorders (8%). Twenty-eight percent had a secondary diagnosis (14.7% a neurodevelopmental disorder and 4% an anxiety disorder).

Most of the sample (85.3%) was right-handed and was not on medication during the evaluation process (82.7%).

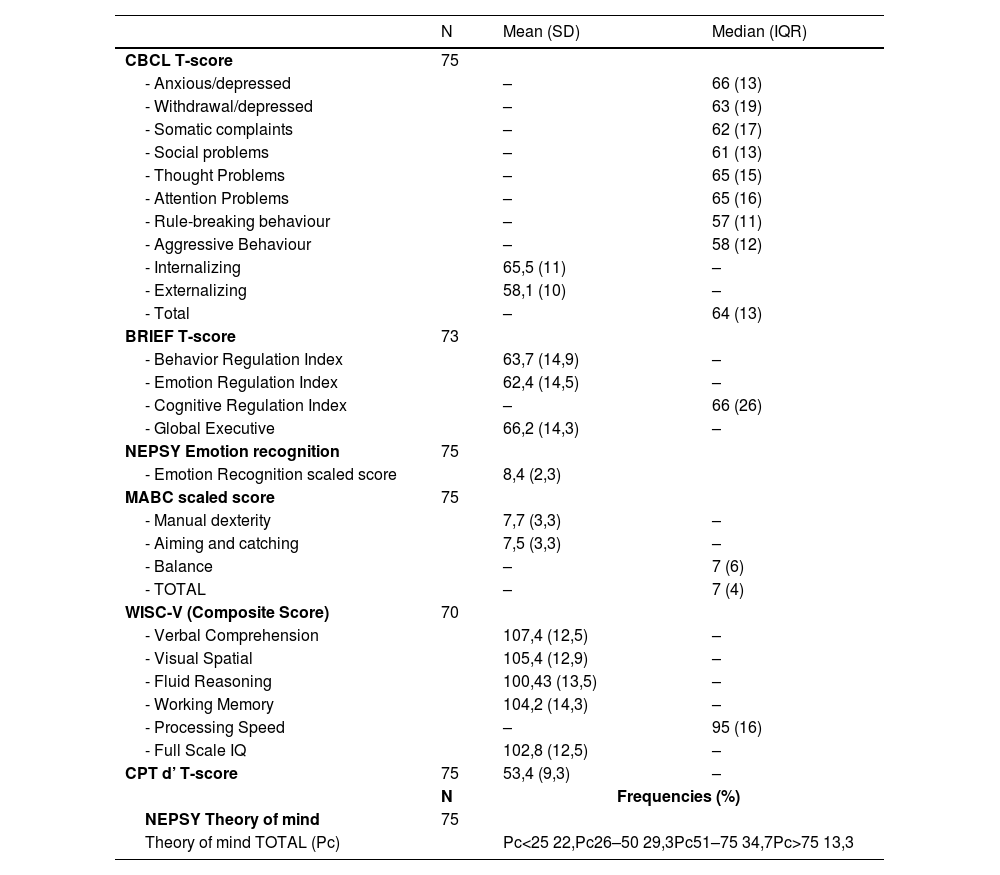

Neuropsychological performance and clinical characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1 (normally distributed variables are described by Mean and SD an non-normally distributed variables by Median and IQR). As a group, internalizing problems, and subscales anxious-depressed, thought problems and attention problems, as well as executive function, fell into the borderline scores. Children´s performance was below expected standardized values by age in emotion recognition (−0,5 SD) and motor function (−1 SD). General intelligence quotient and every WISC-V index were average.

Clinical and neuropsychological characteristics of the sample.

No statistically significant differences were found between both groups in terms of demographics (age, sex, social status, living area), dominant hand or diagnosis status.

However, there was a trend (p = 0.062) towards more secondary diagnosis in FHR-SZ group (35%) than in non-FHR-SZ group (16.7%). Most of the secondary diagnoses in the FHR-SZ group (9 out of 16), were neurodevelopmental disorders.

In terms of clinical and neuropsychological variables, assuming a p = 0.001, only CBCL attention subscale showed differences close to significance (t = 3.1, p = 0.003) with higher scores (meaning more problems) in the non-FHR-SZ group.

Comparison between patients with and without borderline/clinical scores on thought problems (CBCL subscale)The total sample was classified in two groups by means of their score on the CBCL-Thought Problems subscale. The cut-off point was established at T ≥ 65 with the purpose to include those in the borderline and clinical range. Thirty-eight patients fell into the Thought Problems group (TP) (mean=70.8; SD=4.8) and thirty-seven had scores in the normal range (non-TP) (mean=54.7; SD=4.9).

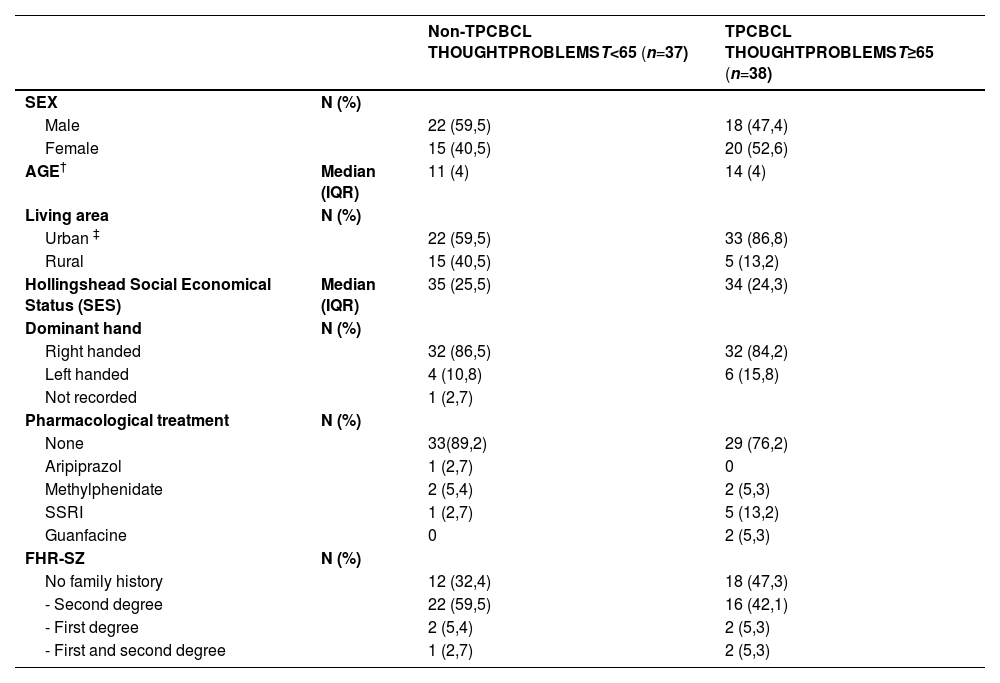

In terms of demographics (Table 2), significant differences were found in age and urbanicity. TP group was older, and a higher proportion lived in urban areas. Both groups were comparable in terms of sex, social status, dominant hand, family history, or medication.

Demographics and characteristics of TP group and non-TP group.

| Non-TPCBCL THOUGHTPROBLEMST<65 (n=37) | TPCBCL THOUGHTPROBLEMST≥65 (n=38) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SEX | N (%) | ||

| Male | 22 (59,5) | 18 (47,4) | |

| Female | 15 (40,5) | 20 (52,6) | |

| AGE† | Median (IQR) | 11 (4) | 14 (4) |

| Living area | N (%) | ||

| Urban ‡ | 22 (59,5) | 33 (86,8) | |

| Rural | 15 (40,5) | 5 (13,2) | |

| Hollingshead Social Economical Status (SES) | Median (IQR) | 35 (25,5) | 34 (24,3) |

| Dominant hand | N (%) | ||

| Right handed | 32 (86,5) | 32 (84,2) | |

| Left handed | 4 (10,8) | 6 (15,8) | |

| Not recorded | 1 (2,7) | ||

| Pharmacological treatment | N (%) | ||

| None | 33(89,2) | 29 (76,2) | |

| Aripiprazol | 1 (2,7) | 0 | |

| Methylphenidate | 2 (5,4) | 2 (5,3) | |

| SSRI | 1 (2,7) | 5 (13,2) | |

| Guanfacine | 0 | 2 (5,3) | |

| FHR-SZ | N (%) | ||

| No family history | 12 (32,4) | 18 (47,3) | |

| - Second degree | 22 (59,5) | 16 (42,1) | |

| - First degree | 2 (5,4) | 2 (5,3) | |

| - First and second degree | 1 (2,7) | 2 (5,3) |

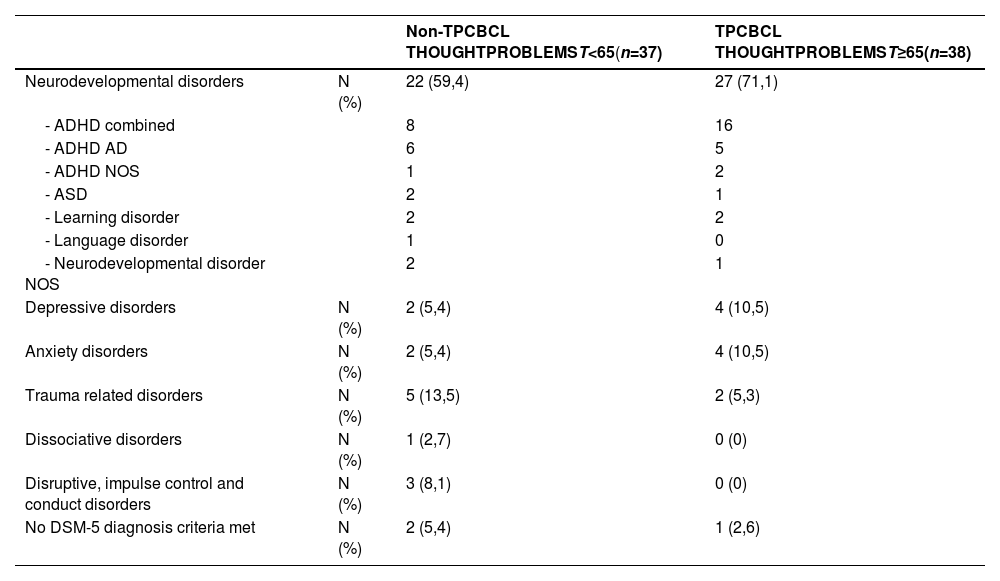

In terms of diagnosis (Table 3), a trend was observed in TP group with a higher proportion of patients diagnosed combined ADHD. Fourteen patients in the TP group versus six patients in the non-TP group received a second diagnosis.

Primary diagnosis in both groups (TP and non-TP).

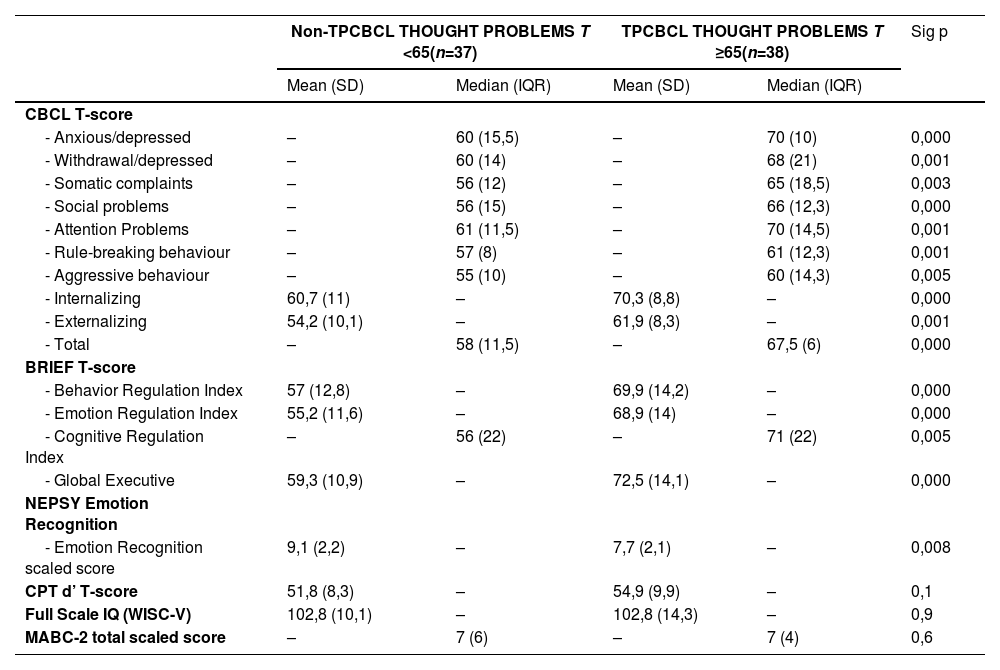

Clinical symptoms measured with CBCL were more severe in the TP group (p = 0,000). The non-TP group had scores in the normal range for every subscale. The TP group had scores in the borderline or clinical range for several subscales anxious/depressed, withdrawal/depressed, somatic complaints, social, and attention problems, Internalizing and Total (Table 4).

Comparison between clinical and neuropsychological variables in both groups (TP and non-TP).

Groups were different in executive function (BRIEF), the TP group had scores in the borderline or clinical range while non-TP scored normal (Table 4).

Regarding Emotion Recognition (NEPSY), TP group performed worse close to significance (p = 0,008) (Table 4), and analysis of the error patterns showed that TP group more often made “angry” errors, meaning that they tended to report “angry” to other emotions (x2=8,94, p = 0,003).

DiscussionTwo main hypotheses were addressed in this study, both with the purpose of identifying a group of patients theoretically more vulnerable to psychosis, which would merit more attention in clinical practice for preventive strategies. Firstly, we looked for differences in cognition, motor development and behaviour in relation to the presence or absence of family history of schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Secondly, we searched if scores on CBCL Thought Problems scale could differentiate a more clinically and developmentally affected group.

In terms of differences between FHR-SZ and non-FHR-SZ groups, no significant differences were found except for a trend to more secondary diagnoses in FHR-SZ patients, mainly developmental disorders. A possible reason for these scarce results is that only 15% of the FHR-SZ group had a first-degree affected relative. FHR-SZ studies usually recruit first-degree family members. When second-degree have been examined, either no differences with typical development34 or intermediate performance in cognitive measures between first-degree and healthy controls are found.35,36 Our whole sample was help-seeking, therefore, differences between two clinical groups may be smaller and, due to sample size, not detected. Moreover, a participation bias could have influenced characteristics of non-FH group because parents are more willing to participate in studies if worried about their children´s symptoms.

Regarding our second hypothesis, some significant and clinically relevant differences were found when the sample was divided by presence (TP) or absence (non-TP) of Thought Problems.

The non-TP group had CBCL subscales and executive function scores in normal range and the TP group was clinically affected in a variety of symptoms.

Firstly, TP group more often received a diagnosis of combined ADHD and more frequently a secondary diagnosis (mainly neurodevelopmental and anxiety disorders). Keshavan37 found high prevalence of ADHD in a FHR-SZ population (30% of the sample) which also associated with more frequent psychosis-like clinical features (magical ideation and perceptual aberration). Several authors have remarked the specific association between ADHD and psychotic disorders. Both disorders share impairments of inattention, executive functions, emotional processing, and social functioning.38 Shared genetic factors of ADHD and schizophrenia are suggested39 as well as the relationship with cannabis use.40 ADHD has been associated with a nearly five-fold increased risk of later psychotic disorders41 and also with poorer clinical response to psychosis treatment.42 Longitudinal studies are needed to clarify if an “ADHD subgroup” within FHR-SZ subjects predict an increased risk for future emergence of schizophrenia.37

Secondly, TP group presented symptoms in the clinical range for Internalizing subscale and, specifically, anxiety/depression and attention problems, and in the borderline range for withdrawal/depression, somatic concerns and social problems. Depressive and anxiety disorders are common comorbid conditions in CHR children and adolescents.43 Dunedin cohort study found that the majority of adults diagnosed with schizophreniform disorder at age 26, had received a prior diagnosis in childhood or adolescence, mainly depression, ADHD and conduct disorders.17 Simeonova23 used CBCL scale as psychosis risk screening in adolescence and found that scores on Withdrawn/Depressed and Thought Problems had clinical and diagnostic utility to aid in early detection. They also found that positive family history (of psychosis or affective disorders in first-or second-degree relative) led to higher scores in several CBCL subscales (anxious/depressed, social problems, thought problems, attention problems, and aggressive behaviour)44 which has not been replicated in our sample.

Thirdly, TP group also had significant problems in executive function. Spang10 found more widespread and severe impairments, already at age 7, in children with parental history of schizophrenia versus bipolar disorder using the same instrument.

Finally, in our study, TP group also performed worse in Emotion Recognition. Moreover, they tended to attribute “angry” to other emotions, which has been found in adolescents at risk for psychosis, and might relate to social self-consciousness or perception of oneself being the target of others’ actions.45 A notable finding in a CHR study is that Emotion Recognition was a significant predictor of psychosis transition and also strongly correlated with subthreshold thought disorder.46 In FHR studies, first-degree relatives had strong deficits, specifically, for recognizing emotions with a negative valence compared to controls.47 Children (aged 9 to 14 years old) with “well-replicated antecedents for schizophrenia” (meeting three criteria: motor/speech abnormalities, psychotic like experiences, and social/emotional/behavioural problems) also presented impairment in facial emotion recognition compared to healthy peers.28 This group of research defends that their strategy recruiting children characterized by “well-replicated antecedents for schizophrenia” rather than selecting children with only one risk factor (i.e. family history or psychotic like experiences for example), may capture a broader range of children at risk. Such an approach is like ours as we look for children with neurodevelopmental or emotional symptoms, thought problems and neuropsychological deficit. Executive function and social cognition have strong evidence as premorbid impairments1 and both are affected in our TP group.

Also, a well replicated environmental risk factor, more frequent urban upbringing, was also found in this TP group.

However, we did not find differences between groups regarding motor function, which was not expected. It has been described that motor signs may be a transdiagnostic marker of vulnerability for psychopathology48 so, given that the whole sample was help-seeking and mainly diagnosed with neurodevelopmental problems, general performance was lower than expected by age and probably not specific for our discriminative purposes.

While the premorbid trajectory of these difficulties remains unclear, it is crucial to follow up samples enriched for psychosis risk.49 The combination with biological markers could guide in the detection of at-risk cases early in development. In this regard, schizophrenia polygenic risk score has been associated with CBCL Internalizing symptoms and Thought Problems at age 10, while no associations were observed for other psychiatric illnesses.50 Some promising data have associated activation in the precuneus/posterior cingulate cortex during self-referential processing with CBCL Internalizing scores (with specific correlations with Thought Problems, Social Problems and Withdrawn) in FHR-SZ children aged 7–12 years. Therefore, these abnormalities found in patients with schizophrenia and unaffected relatives seem to be present before adolescence.51

In clinical staging models, illness transcends the boundaries of diagnostic criteria emphasizing prevention efforts in a more developmental and transdiagnostic approach.52 Intervention strategies in adolescents at ultra-high-risk have limited impact on functional outcome as cognitive and social deficits start much earlier.53 Targeting behaviors leading to better social function seems a relevant entry point in childhood and adolescence given that negative symptoms related with social behavior are predictive of psychosis conversion54 and some evidence suggests that the roots of residual social functioning in schizophrenia spectrum disorders may come from an arrested development in the specialization of social cognition during adolescence.55 There is evidence that children and adolescents with social deficits might benefit from behavioral interventions targeting social function and social cognition regardless of their specific neurodevelopmental or mental health diagnosis.56

This study has several limitations. First of all, the modest sample size, and small proportion of first-degree relatives with Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders, limit the statistical power to detect differences between groups with and without family history. Larger samples and first-degree probands would be needed to delineate risk profiles. Also, we did not recruit a non-clinical control group for comparison, although we used standardized tests widely used in clinical practice and research in childhood and adolescence. Another limitation is the reliance on parents’ report on family history, which we could not confirm, and that we did not include subjects with family history of other severe mental disorders, which confers transdiagnostic risk. Moreover, some relevant cognitive variables were not evaluated (i.e. verbal learning and memory).

ConclusionsIn children attending a psychiatric clinic, an elevated score on CBCL Thought Problems subscale associate with more urban upbringing, more frequent combined-ADHD diagnosis, more internalizing clinical problems (mainly anxiety/depression, withdrawal/depression and attention problems, but also somatic complaints and social problems) and difficulties in executive function and emotion recognition, with a specific tendency to report “angry” to other emotions. This group would merit more attention in clinical practice for preventive strategies and follow up until adulthood.

Ethical considerationsThis study was approved by the ethics committee of Clinic University Hospital of Valladolid. All patients and parents/guardians provided informed consent before participation.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

We would like to express our gratitude to all the children and parents who participated in this study.