The presence of substantial evidence regarding the association between dietary niacin intake and cognitive impairment among the elderly remains limited, with inconsistent findings. Thus, the objective of this study was to assess the aforementioned relationship, utilizing data obtained from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

MethodsThis cross-sectional study analyzed 2255 participants aged ≥60 years from NHANES 2011–2014.The assessment of dietary niacin intake was conducted through two 24-hour dietary recalls, while cognitive function was evaluated using a battery of five tests. Multivariable logistic regression models and generalized additive model (GAM) was utilized to investigate the association between dietary niacin intake and cognitive impairment. Furthermore, subgroup analysis was conducted to assess the robustness of the primary findings.

ResultsA total of 2255 old adults were included in this study, of whom 47.9% were male. In the fully adjusted model, we observed a significant inverse association between dietary niacin intake and cognitive decline [as a quartile variable, Q4 vs. Q1, odds ratio (OR):0.5 and 95% confidence interval (CI): (0.35∼0.72), p < 0.001; as a continuous variable, per 1 mg/day increment, OR (95%CI):0.97(0.95∼0.98), p < 0.001].The smooth curve fitting results revealed that A linear relationship was found between niacin intake and cognitive impairment in elderly people. The results of the sensitivity analysis remained stable.

ConclusionsDietary niacin intakes might be inversely associated with the prevalence of cognitive impairment. Further research is required to confirm this association.

The urgency of maintaining cognitive function in the aging population of the United States is growing due to the rising life expectancy.1 The World Health Organization projects that the number of individuals aged over 60 will reach 65.7 million by 2030 and possibly 115.4 million by 2050.2,3 The prevalence of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) among the elderly population has been reported as high as 42%, underscoring the critical importance of early intervention and risk factor assessment to prevent cognitive decline.4,5 Research has demonstrated that significant decline in cognitive function can profoundly impact social and cognitive development.6 Consequently, understanding the factors that can mitigate the risk associated with low cognitive performance is crucial. In recent years, the influence of nutrition on cognitive function has garnered increasing attention.7

Niacin and nicotinamide, collectively known as niacin, serve as dietary precursors for nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP).8 These coenzymes participate in redox reactions essential for energy production. Specifically, pyridine rings can function as electron carriers, accepting or releasing hydride ions.9,10 NAD serves as a substrate for ADP-ribosyltransferase, an enzyme that catalyzes the transfer of ADP-ribose. This reaction results in the breakdown of NAD into nicotinamide and ADP-ribosyl products, which are involved in various cellular processes such as gene expression, cell cycle progression, insulin secretion, and DNA regulation. This signaling cascade plays a vital role in apoptosis and senescent cells.11,12 Niacin is found in a variety of whole and processed foods, including meat from various animal sources, seafood, and spices.13 When considering the detailed food products, the highest ranked food sources of niacin were processed meat products (14.4%), pork (13.0%), chicken (11.9%), liver and organ meat (2.5%) and other meat products (2.3%).14

Although the direct cause of cognitive impairment remains unclear, numerous studies have demonstrated the significant roles of niacin in various processes, such as DNA synthesis and repair, myelination and dendritic growth, cellular calcium signaling, and its potent antioxidant properties in brain mitochondria.15-18 European trials examining pharmacological preparations containing nicotinic acid have reported enhancements in cognitive test scores and overall function.19-21 However, limited research has been conducted on the association between dietary niacin and the development of cognitive impairment. Two case-control studies revealed lower levels of a nicotinic acid metabolite in demented patients compared to age and sex-matched controls.22,23 Nevertheless, there is a scarcity of investigations examining the relationship between niacin intake and cognitive impairment in a large sample population. Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate this association in elderly individuals by utilizing data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

MethodsData sources and study populationThe NHANES is a nationally representative cross-sectional study that employs a stratified multistage probability and oversampling design to ensure the analysis accurately represents the noninstitutionalized, civilian population of the United States (US).24 Data from the study are released biennially, and each participant represents approximately 50,000 US citizens. Trained staff, including physicians, dentists, health technologists, interviewers, and laboratory technicians, administer standardized interviews and examinations.25 For comprehensive information on the NHANES study design, recruitment, procedures, and demographic characteristics, the CDC website (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm) provides complete details.26 In summary, the NHANES study implemented a four-stage design with oversampling of specific subgroups to enhance precision. An advanced computer system collects and processes all NHANES data. The survey findings are instrumental in determining the prevalence of diseases and associated risk factors.

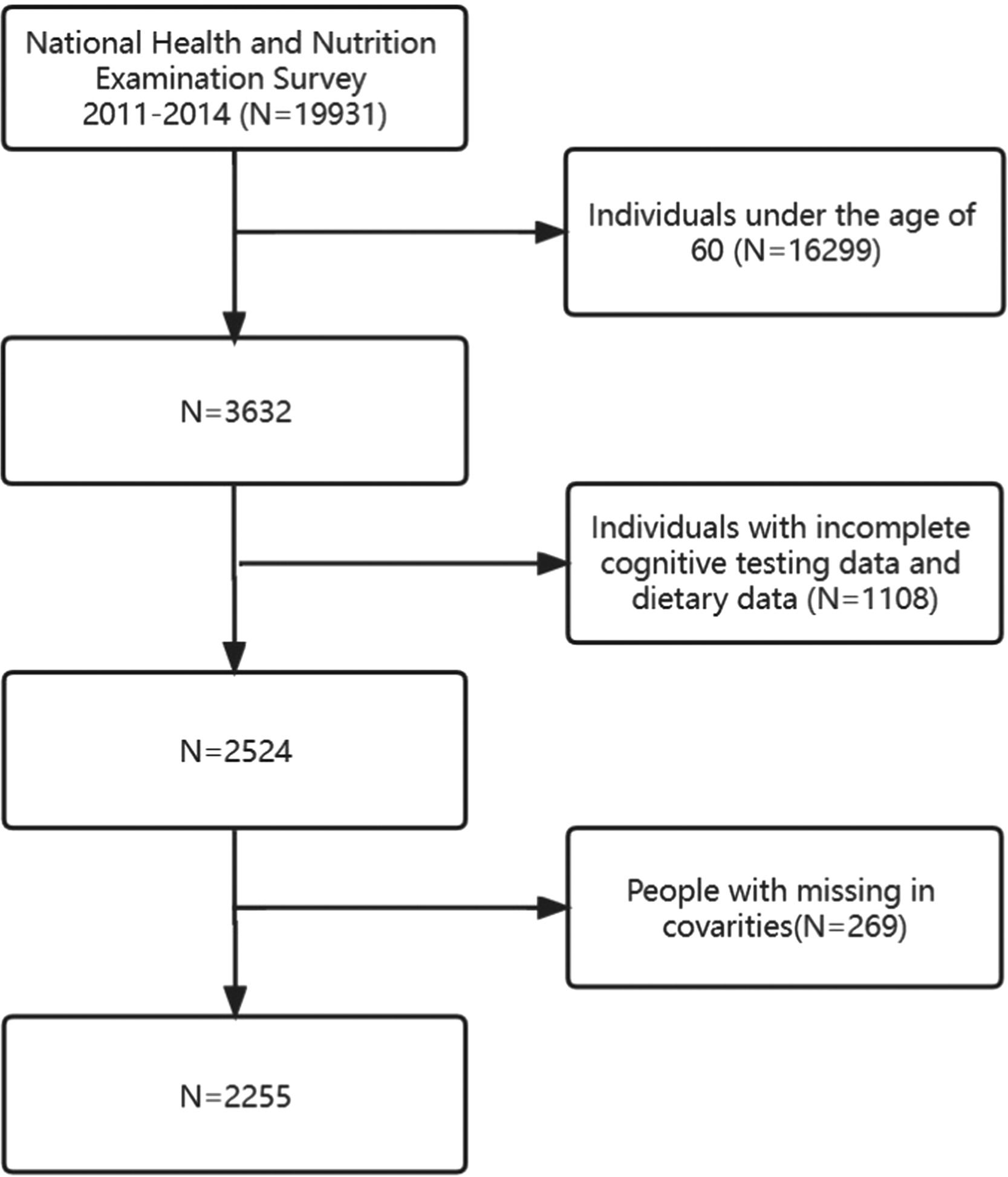

During the 2011–2014 cycle, a total of 19,931 participants were initially included in the study. Exclusions were made for individuals under 60 years old (n = 16,299), with incomplete cognitive data and incomplete dietary retrospective survey data (n = 1108), and finally those with missing covariates (n = 269). Ultimately, a total of 2255 participants met the eligibility criteria and were included in the study. The selection process and search strategy are illustrated in detail in Fig. 1, which provides a flowchart of the study. NHANES received approval from the NCHS Research Ethics Review Board, and all participants provided written informed consent.27 All procedures conformed to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE).

Dietary niacin intakeDietary intake interviews were conducted through in-person sessions at the NHANES mobile examination clinics.28 Two 24-h dietary recalls were employed to gather dietary intake data from NHANES participants.29 The initial 24-h recall interview took place face-to-face at the Mobile Examination Center (MEC), conducted by trained interviewers. The second interview occurred via telephone or mail within a span of three to ten days.30 The dietary assessments were based on the average of the two 24-h recalls. According to the NHANES analytic guidelines, the sum of dietary niacin intake and niacin supplementation was considered as Niacin intake. Niacin intake was analyzed both as continuous variables and categorical variables (Q1-Q4). The cutoff values represent 25%, 50%, and 75% of the total sample intake of niacin, respectively. Niacin intake quartiles (Q1-Q4) were determined by dividing the distribution of Niacin intake into four parts, representing low to high intake levels. The range of quartiles (Q1–Q4) are as follows: Q1(<15.55 mg/day), Q2(15.55–20.83 mg/day), Q3(20.83–27.25 mg/day), Q4(>27.25 mg/day)

Cognitive functionWe examined five cognitive outcomes: Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease Word Learning (CERAD-WL) Immediate Recall, CERAD-WL Delayed Recall, Animal Fluency Test (AFT), Digital Symbol Substitution Test (DSST), and Z test (Z). The Alzheimer's Disease Registry Consortium (CERAD) was established as a comprehensive test battery to evaluate new learning, memory delays, and cognitive memory abilities in individuals with dementia.31 The memory assessments comprised immediate and delayed recall of logical and word list material.32 The AFT evaluated category fluency by requesting participants to generate as many animal names as possible within a 60-second trial.33 The DSST measured psychomotor skills using a paper-and-pencil task involving number-symbol substitution, where subjects filled in empty boxes based on a provided grid.34 To determine z-scores specific to each test (including DSST, CERAD-WL Delayed Memory, CERAD-WL Immediate Memory, and AFT), we computed them using the sample means and standard deviations of test results.35 The global Z score is a summary of all the cognitive tests and higher Z score is associated with better cognitive function. Regardless of the type of cognitive test, higher scores in each test are associated with better cognitive function, in order to evaluate the patient's cognitive function.

CovariatesCovariates in this study were initially selected based on a combination of clinical experience and a thorough review of relevant literature. The examined covariates encompassed age, race, gender, poverty-income ratio (PIR), education, body mass index (BMI), and various health conditions such as heart failure, coronary disease, angina, stroke, hypertension, smoking, alcohol use, and diabetes. Respondents were categorized into three age groups: 60–69, 70–79, and 80 or older.36 Racial and ethnic groups were defined according to NHANES categories, including Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Mexican–American, Non-Hispanic Asian, Other Hispanic, or Other/Mixed race.37 Gender variables were classified into two categories: female (F) and male (M). The poverty-income ratio served as an indicator of poverty status, calculated by dividing total household income by the poverty line.38 Education levels were categorized as less than high school, completed high school, or beyond high school. Weight status was determined using standard BMI cutoffs, with normal weight defined as BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m2, overweight as BMI 25–29.9 kg/m2, and obese as BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2.39 Cardiovascular disease included congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, angina, myocardial infarction, stroke, and hypertension.40 Smoking status was classified as follows: never smoked but not currently, smoked 100 cigarettes in their lifetime but currently none, and current smoker but smoked 100 cigarettes in their lifetime.41 NHANES employed the Alcohol Use Questionnaire (ALQ) to collect data on alcohol use in the past 12 months for respondents aged 20 and over as part of the mobile screening component.42 For NHANES, diabetes status was determined based on the participant's physician's diabetes diagnosis report.43

Statistical analysisData were categorized into continuous and categorical variables. Continuous variables were further classified based on their distribution normality. Normally distributed continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation and compared using Student's t-test. Non-normally distributed variables were presented as median ± interquartile range (IQR) and compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Categorical variables were presented as percentages and compared using the chi-square test. The significance of differences among groups stratified by quartiles of dietary niacin intake was assessed using the Kruskal-Wallis test or one-way analysis of variance.

Furthermore, the association between dietary niacin intake and Low Cognitive Performance was investigated using multivariate logistic regression. In accordance with NHANES analytic guidelines, the sum of dietary niacin intake and niacin supplementation was considered as Niacin intake. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to assess the relationship between dietary niacin intake and Low Cognitive Performance. Dietary niacin was examined as both a continuous and categorical variable in the multivariate logistic regression analysis. Model 1 was the crude model without any adjusted covariates. Model 2 adds sociodemographic variables (age, sex, race and ethnicity, educational level, poverty-income ratio) to Model 1; Model 3 adds body mass index, heart failure, coronary disease, angina, stroke, hypertension, smoking, alcohol consumption, and diabetes to Model 2. The prevalence of low cognitive level and normal cognitive level in adults over 60 years old was compared between the lowest quartile group of niacin consumption and the other groups.

Finally, account for non-linear relationship between niacin intake and Low Cognitive Performance, we also used Generalized additive model and the smooth curve fitting (penalized spline method) to address nonlinearity. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. To identify modifications and interactions, we used a stratified linear regression model and likelihood ratio test in subgroups of age (60–70,70–80 or ≥80 years), sex (female or male), BMI (<25 kg/cm2,25–30 kg/cm2 or ≥30 kg/cm2), Education (below high school, high school or over high school) and PIR (<1.3 vs. ≥1.3)

All analyses were performed using the statistical software package R. version 4.1.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and Free Statistics software version 1.7. P values < 0.05 (two-sided) were considered statistically significant. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement were followed when reporting this cross-sectional study.

ResultsBaseline characteristics of selected participantsTable 1 summarizes the baseline clinical characteristics of the patients included in the study. The participants' baseline characteristics were categorized according to their niacin intake quartiles: Q1(<15.55 mg/day), Q2(15.55–20.83 mg/day), Q3(20.83–27.25 mg/day), Q4(>27.25 mg/day). Analysis of the data from Table 1 reveals that 15.5% of the respondents were aged 80 or older, 51.4% were non-Hispanic White, and 47.9% were male. Moreover, 39.0% of the respondents were classified as obese with a body mass index (BMI) exceeding 30. Furthermore, the analysis indicates that individuals with higher niacin intake tended to be younger, male, have higher family income and education levels, a lower incidence of heart failure, a higher prevalence of alcohol consumption, and higher scores in the AFT, DSST, and Z tests.

The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population. (N = 2255).

Abbreviations:%, weighted proportion.; CERAD, Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's disease; CERAD-DR, delayed recall in CERAD trial;.

CERAD-IR, immediate recall in CERAD trial;DSST,Digit Symbol substition test:SD,standard deviation,AFT, Animal Fluency Test.Z test is average of IR,DR,AFT,DSST.

Niacin is in the quartile.

Q1(<15.55 mg/day), Q2(15.55–20.83 mg/day), Q3(20.83–27.25 mg/day), Q4(>27.25 mg/day).

Table 2 presents the relationship between dietary niacin intake and cognitive impairment using multiple logistic regression models. The global Z test reveals a negative correlation between dietary niacin intake and cognitive impairment overall. In the adjusted model, which accounts for age, race, gender, poverty-income ratio, education, there is a negative association between dietary niacin intake and cognitive impairment (odds ratio [OR], 0.96; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.95–0.98; P < 0.001). This association remains significant even after adjusting for all potential covariates (fully adjusted model, Table 2), indicating a negative relationship between dietary niacin intake and cognitive impairment as a continuous variable (OR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.95–0.98; P < 0.001; Table 2). Moreover, when dietary niacin intake is considered as a categorized variable, there is a consistent pattern across different dietary niacin intake groups. The highest dietary niacin intake group (Q4) exhibits a 50% lower incidence of cognitive impairment (OR, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.35–0.72; < 0.001) compared to the lowest dietary niacin intake group (Q1) (Table 2).

Multivariable logistic regression to assess the association of niacin Intake with Cognitive score.

Niacin enter as a continuous variable per 1 mg/day increase.

Model 1: No adjustment.

Model 2: Adjusted for age, race, gender, Poverty-income ratio, education.

Model3: Adjusted for age, race, gender, Poverty-income ratio, education, Body mass index, Heartfailure, coronary disease, angina, stroke, Hypertension, Smoking, Stroke, Alcohol, Diabetes.

Abbreviations:%, weighted proportion.; CERAD, Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's disease.

CERAD‐DR, delayed recall in CERAD trial.

CERAD-IR, immediate recall in CERAD trial.

DSST,Digit Symbol substition test:SD,standard deviation,AFT, Animal Fluency Test.

AFT, Animal Fluency Test.Z test is average of IR,DR,AFT,DSST.

CI:confidence interval; OR: odds ratios, Ref:reference.

Niacin is in the quartile.

Q1(<15.55 mg/day), Q2(15.55–20.83 mg/day), Q3(20.83–27.25 mg/day), Q4(>27.25 mg/day).

This study utilized a logistic regression model combined with a generalized additive model (GAM) to evaluate the correlation between niacin intake and low cognitive performance. The distributions and smoothing curve fit between the variables, along with the 95% confidence interval of the curve fit, are illustrated in Fig. 2. By accounting for various confounding factors such as age, race, gender, poverty-income ratio, education, body mass index, heart failure, coronary disease, angina, stroke, hypertension, smoking, alcohol consumption, and diabetes, a linear association was observed between dietary intake and cognitive impairment. To accommodate space constraints, the results of the curve-fitting analyses for DSST, AFT, DR, and IR tests can be found in Supplementary Figs. 1–4, respectively.

Dose-response relationship between dietary niacin intake and cognitive impairment in Z test. Solid and dashed lines represent the predicted value and 95% confidence intervals. Adjusted for age, race, gender, Poverty-income ratio, education, Body mass index, Heartfailure, coronary disease, angina, stroke, Hypertension, Smoking, Stroke, Alcohol, Diabetes. Only 99% of the data is shown. Abbreviations: Z score is average of CERAD.IR, CERAD.DR, AFT, DSST. CI:confidence interval; OR: odds ratios, Ref:reference. NIAC is the abbreviation for niacin.

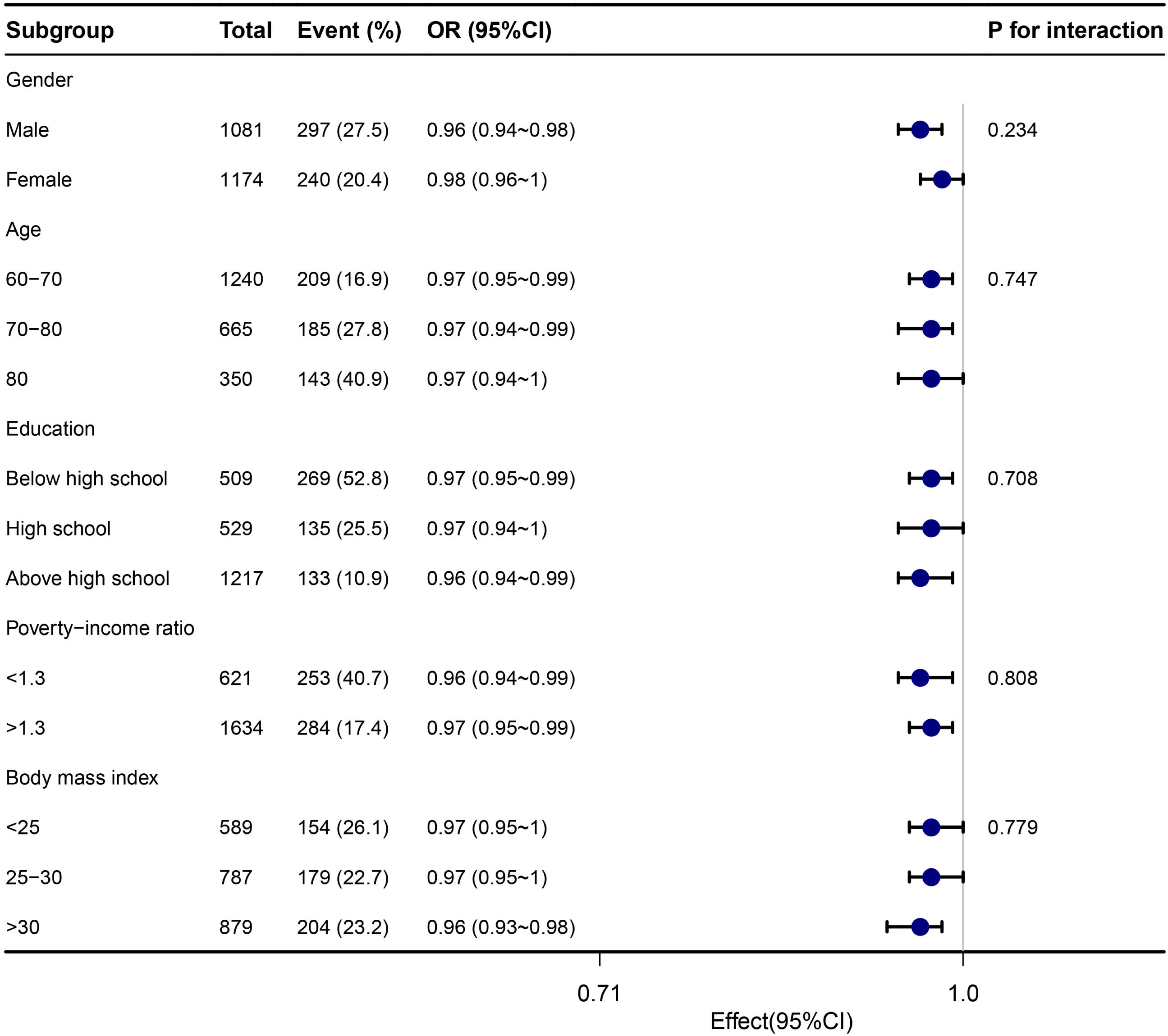

To explore additional factors that may influence the association between dietary niacin intake and cognitive impairment, subgroup analyses were conducted based on stratification variables including age, sex, education level, poverty-income ratio, and BMI. The findings from the subgroup analyses and Z-test interactions were summarized in Fig. 3, which indicated no statistically significant relationships observed across any of the subgroups (P < 0.05). For the subgroup analyses related to DSST, AFT, DR, and IR tests, we present the results in Supplementary Figures 5, 6, 7, and 8 due to space limitations.

Stratified analyses of the association between dietary niacin intake and cognitive impairment according to baseline characteristics in Z test. Note: The p value for interaction represents the likelihood of interaction between the variable and niacin intake. Abbreviations: OR, odd ratio; CI, confidence interval.

This cross-sectional study analyzed data from 2011 to 2014 to investigate the association between dietary niacin intake and cognitive impairment in older adults. Multivariate logistic regression was employed to estimate the odds ratio (OR). The findings revealed an inverse relationship between dietary niacin intake and cognitive impairment. Additionally, smooth curve fitting confirmed a significant linear correlation between the two variables. Stratified and sensitivity analyses provided further support for the robustness of our results. These findings hold clinical significance as they enhance our understanding of the importance of niacin intake among the elderly.

The impact of nicotinamide on cognitive function is most prominently observed in cases of explicit deficiency, notably pellagra-induced dementia. Although this condition is now rare in developed nations, it can still be found in individuals with excessive alcohol consumption, drug dependence, dietary restrictions, malabsorptive disorders, HIV infection, carcinoid syndrome,44 or among long-term institutionalized patients.45 Nonetheless, with the aging population and the accompanying cognitive decline, there is a growing interest in determining whether nicotinamide supplementation can play a role in preserving or enhancing cognition. Neurocognitive decline among the elderly is often multifaceted. Malnourishment is not uncommon, particularly among those in long-term care facilities, and it is known that improved nutrition correlates with better cognitive performance.46,47 Additionally, the elderly may have diminished ability to effectively utilize nutrients. However, an observational study involving 75 long-term care patients did not find a significant difference in cognitive function, as measured by the standardized mini-mental state examination, between patients with niacin deficiency (defined as a niacin ratio [NAD/NADP] of ≤1) and non-deficient patients.45 Another observational study reported a reduced relative risk of Alzheimer's disease (AD) and lower levels of cognitive decline associated with increased dietary intake of vitamin B3.48 This study involved 3718 subjects from the Chicago Health and Aging Project and utilized a Food Frequency Questionnaire to determine vitamin B3 intake. Participants were categorized into quintiles based on niacin intake, with the lowest quintile having a median intake of 12.6 mg/day and the highest quintile having 22.1 mg/day. Clinical assessment for AD was conducted by a neurologist on 815 of the 3718 subjects. The study revealed a crude adjusted relative risk for AD of 0.4 per 7.2 mg/day increase in dietary niacin. For the entire group of 3718 subjects, an association was found between increased niacin intake from food and decreased cognitive decline over a median follow-up period of 5.5 years, as assessed by the East Boston Test of Immediate and Delayed Recall, the MMSE, and the Symbol Digit Modalities tests. However, it is important to note that this study relied on patient recall through a Food Frequency Questionnaire, which is a limitation. The NHANES study provides a unique opportunity to examine the link between dietary niacin and lower cognition, as well as to explore the dose-response relationship between the two using multivariate and multilevel analyses.

This study highlights a significant finding regarding the relationship between dietary niacin intake and low cognitive performance, as revealed by the dose-response analysis. As explain in Table 1, the analysis indicates that individuals with higher niacin intake tended to be younger, male, have higher family income and education levels, a lower incidence of heart failure, a higher prevalence of alcohol consumption. These factors explain partly the association with a better cognitive function. The stability of these results was confirmed through the sensitivity analysis, emphasizing the importance of monitoring the dietary intake of the elderly, as it may impact the occurrence of cognitive impairment. In the supplementary figure, we can observe similar phenomena in any commonly used cognitive test, indicating that the association between niacin intake and cognitive function is stable. To enhance niacin intake, incorporating niacin-rich foods such as fish, meat, milk, peanuts, and fortified flour into the diet is recommended.8 According to the Dietary Reference Intakes, individuals aged 65 years or older have an average niacin requirement of 11 mg/day, with a recommended intake of 14 mg/day. The recommended intake of niacin was met in the second, third, and fourth quartiles of niacin intake.13

Although the precise mechanisms behind the negative association between niacin intake and lower cognitive performance are not yet fully understood, our findings align with current biological evidence. Two primary mechanisms being investigated are mitochondrial dysfunction and reduced brain inflammation. Mitochondrial dysfunction, which relies on significant energy consumption within the mitochondrial energy pathway, leads to NAD-consuming enzymes reducing NAD levels. This reduction limits the production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), resulting in insufficient cellular energy and subsequent cognitive decline.49 Notably, the loss of NAD+ and mitochondrial dysfunction are commonly observed in aging and Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis, affecting synaptic plasticity.50,51 Additionally, increasing NAD+ concentration in the brain has been shown to restore mitochondrial function and counteract cognitive decline in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease.50,52

NAD, a coenzyme derived from nicotinamide, exhibits potential beneficial effects on brain inflammation. Nicotinamide, a variant of vitamin B3, possesses anti-inflammatory properties and inhibits NF-κB, a protein complex that plays a crucial role in inflammation, via SIRT1-mediated deacetylation.53 Similarly, nicotinamide riboside, another form of vitamin B3, has demonstrated the ability to mitigate DNA damage, neuroinflammation, and neuronal cell death in the hippocampus. It also shows promise in reducing the accumulation of phosphorylated tau, a characteristic feature of Alzheimer's disease, in a mouse model with impaired DNA repair mechanisms.54 Furthermore, the administration of niacin or niacinamide has shown protective effects against neuroinflammation induced by a high saturated fat diet in mice with compromised blood-brain barrier integrity.55 These findings collectively suggest that supplementing NAD+ may hold therapeutic potential for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease and other neurodegenerative conditions.

The method employed in this study offers several advantages. Firstly, it is the first investigation to examine the association between dietary niacin intake and cognitive impairment among older individuals in the United States. Secondly, a smoothing function analysis was applied to the data to mitigate potential contingencies in the data analysis, thereby elucidating the relationship between TG/HDL-C and hypertension. Additionally, this study assessed dietary niacin intake both as continuous and categorical variables, reducing contingency and enhancing result robustness. Nonetheless, there are certain limitations to our study. Firstly, due to its cross-sectional design, we were unable to establish a temporal relationship between dietary niacin intake and cognitive decline. Therefore, future prospective cohort studies are required to validate our findings. Furthermore, the self-reported nature of the interview data and the 24-hour dietary assessments utilized in this study may be susceptible to recall and reporting bias, despite the validation of these assessment tools in other studies. Moreover, due to the limitations of publicly available databases, psychiatric diseases may not be fully considered as a covariate, which may have some impact. In future research, we plan to utilize our own database to address this limitation and explore related areas further. Lastly, the study participants were confined to a population of 2255 Americans aged over 60 years, limiting the generalizability of the results beyond this age range. It is imperative to consider this factor when extrapolating the findings to other populations. Given these limitations, well-designed multicenter controlled trials are necessary to corroborate our findings.

ConclusionThis study found dietary niacin intakes might be inversely associated with the prevalence of cognitive impairment from NHANES. Our findings may contribute to further studies on its pathogenesis and to the literature.

Author contributionsConceptualization: KZ, JYX and RH. Data curation: TYC. Formal analysis: XYQ. Investigation: ZYH. Methodology: MG. Project administration: JGC, BWC. Resources: ZZG. Software: FMG. Supervision: JYZ. Validation: YFG. Visualization: YH. original draft: KZ. Writing: KZ, BL, TLZ. Review & editing: KZ, BL, TLZ.

Data availabilityOur research is based on public data from the NHANES, all details are from the official website (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm). To obtain the application executable files, please contact the author Kai Zhang by email zhangkai7018@jlu.edu.cn.

Ethics approval and consent to participateThe survey protocol for the NHANES was approved by CDC's National Center for Health Statistics Institutional Research Ethics Review Board. All participants provided written informed consent, and the study was approved by the NCHS Research Ethics Review Board (https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/continuousnhanes/default.aspx).

Funding statementThe study has no Foundation.

We appreciate Dr. Jie Liu of the Department of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery, Chinese PLA General Hospital for statistics, study deign consultations and editing the manuscript.