The hostile environment in Paediatric Intensive Care Units (PICU) favours sleep-wake biorhythm dysregulation. Sleep disorders have detrimental impact on the immune, neurological and cardiovascular systems, in addition to increasing morbidity and mortality rates. Sleep plays a crucial role in brain development, rendering paediatric patients particularly vulnerable to the adverse effects of sleep disorders due to their ongoing neurological growth. The factors that affect rest include, among others, noise, lighting, treatment, and nocturnal nursing interventions, although the evidence for the latter is still scarce.

ObjectiveTo identify the nocturnal nursing interventions, following the NIC Taxonomy, carried out in PICUs.

MethodA Multicentre, cross-sectional, descriptive study was performed using an ad hoc survey to identify nocturnal nursing interventions in the PICU. The collected variables were characteristics of the participating PICU and those derived from the nursing interventions. During the analysis, mean and standard deviation of quantitative variables, and frequency tables and percentages were generated for qualitative variables. The variables were operationalized and Student's t-test and ANOVA were calculated for comparison between variables.

Results100 records were obtained, encompassing 5017 interventions, with the most repeated intervention being “Vital signs monitoring”. The mean number of different interventions identified was 23 ± 7.66 and the mean frequency of these was 50.17 ± 19.28. There were significant differences between the hospital variable and the number and frequency of interventions performed (P < .001).

DiscussionWe agreed with other studies in identifying “Vital signs monitoring” as the most frequent intervention. “Improving sleep” was one of the most frequently reported, in contrast to other studies where interventions related to rest were not documented.

ConclusionsThe most frequently performed interventions in the PICU were identified. In most of the registers some intervention on improving rest was identified, which could indicate the latent concern of the health care professionals for the sleep of the critical child.

El entorno hostil de las Unidades de Cuidados Intensivos Pediátricos(UCIP) favorece la desregulación del biorritmo sueño-vigilia. Los trastornos del sueño tienen consecuencias negativas sobre el sistema inmune, neurológico o cardiovascular, además de aumentar la morbimortalidad. El sueño juega un papel fundamental en el desarrollo cerebral, lo que hace al paciente pediátrico especialmente vulnerable a las consecuencias negativas de los trastornos del sueño por encontrarse en pleno crecimiento neurológico. Los factores que afectan al descanso son el ruido, luces, tratamiento o las intervenciones enfermeras nocturnas, aunque la evidencia es escasa para esto último.

ObjetivoIdentificar las intervenciones enfermeras nocturnas, siguiendo la taxonomía NIC, realizadas en UCIP.

MétodoSe realizó un estudio descriptivo transversal multicéntrico empleando un formulario de recogida ad hoc en el que se identificaron las intervenciones enfermeras nocturnas en UCIP. Las variables fueron características de las UCIPs e intervenciones enfermeras. Se calculó media y desviación estándar de las variables cuantitativas y tablas de frecuencias y porcentajes para cualitativas. Para el análisis bivariado se operativizaron las variables y se calculó t de Student y ANOVA.

ResultadosSe obtuvieron 100 registros, con una frecuencia de 5017 intervenciones, siendo la más repetida «monitorización de signos vitales». La media de intervenciones diferentes realizadas fue 23 ± 7,66 y, la media de su frecuencia 50,17 ± 19,28. Existen diferencias significativas entre el hospital y las intervenciones nocturnas registradas (p < 0,001).

DiscusiónSe encuentran coincidencias en identificar «monitorización de signos vitales» como intervención más frecuente. «Mejorar el sueño» fue otra de las intervenciones más repetidas en contraste con otras investigaciones en las que no se recogieron intervenciones relacionadas con el descanso.

ConclusiónSe identificaron las intervenciones enfermeras con mayor frecuencia en UCIP. En la mayoría de registros se identificó alguna intervención sobre mejora del descanso, indicativo de la preocupación latente de los sanitarios por el sueño del niño crítico.

- -

Sleep disorders are frequent at intensive care units (ICUs), and this increases morbidity due to long-term alterations in memory, mobility and post-traumatic stress.

- -

Children, who are in the midst of a period of neurological growth, are particularly vulnerable to the negative consequences of sleep disorders, since the brain undergoes repair processes during this time.

- -

Lights, continuous noise, uninterrupted treatment and night-time nursing interventions, such as vital sign monitoring, disrupt sleep at an ICU.

- -

Night-time nursing interventions were identified for the first time in paediatric ICUs of the National Healthcare System applying the NIC taxonomy.

- -

None of the participating paediatric ICUs had a sleep protocol.

- -

It was observed that the hospital where care is provided might affect the number of night-time interventions, independently of the level of care of the paediatric ICU.

- -

The identification of nursing interventions facilitates a critical reflection about them, as well as the implementation of sleep protocols at paediatric ICUs.

- -

The application of these protocols has been proven to significantly increase the percentage of children who sleep without interruptions.

- -

It is essential that these protocols include the planning of nursing interventions, pain management, light and noise control, as well as the promotion of caregiver presence.

Critical paediatric patients are those who experience a severe illness involving dysfunction, potentially life-threatening organ damage or multisystem failure, including those requiring stabilisation following complex surgery. Illness in critical children is diverse, encompassing pulmonary, hemato-oncological, metabolic, cardiovascular and neurological disease, as well as sepsis and polytrauma patients.1

Due to the severity/complexity of their condition, these patients require admission to a specialised unit: the paediatric intensive care unit (PICU). Given the aforementioned characteristics of critically ill patients, PICU care is based on observation, application of nursing care and uninterrupted treatment.1,2

The main environmental characteristics of a PICU are continuous light and noise.3,4 An ICU is one of the noisiest services, surpassing the night-time level of 35 dB recommended by the WHO,4,5 with documented peaks of 80 dB.6,7 In terms of light, critically ill patients are excessively exposed to artificial light during the night and insufficiently exposed to natural light during the day.2,8 Other characteristics typical of these environments are invasive procedures and patients finding themselves in an unfamiliar location.2,9 All of this entails that PICUs are perceived as hostile by patients and their families.

Other situations experienced by critically ill children arise from their treatment and care, including mechanical ventilation, sedation, enteral feeding and nursing interventions, even during the night.2,10–12

This environmental hostility, added to the continuous care and treatment, contributes to circadian dysregulation, which negatively affects the primary biorhythm; the sleep-wake cycle.2,5–7,10,13

The history of concern about rest in the ICU dates back to 1980, when the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses declared sleep as a priority, with the first studies taking place in 1990.2 In addition, the 1960s saw the emergence of chronobiology, the science in charge of studying biorhythms and their application in medicine. From that moment onwards, interest in the study of these rhythms and their influence on disease has grown steadily.14

Although evidence about sleep patterns in PICUs is increasing, this field of study tends to focus on adult ICUs.2 Nevertheless, in both cases it is concluded that the sleep of critically ill patients is fragmented, inefficient and with abnormal architecture, thus increasing daytime sleep hours.15–18 In addition, the prevalence of sleep disturbances among critically ill patients surpasses 50%, and there are currently no studies conducted in PICUs.19,20

The negative consequences of this issue include alterations in the immune system and metabolism related to melatonin, a hormone involved in adaptive response and the process of glucose transformation. Other studies have reported neurological alterations, such as hyperalgesia, and an increase in the incidence of delirium, related to an extension of admission days, which can sometimes reach double the average figure.21 Moreover, the relationship between delirium and sleep disorders is two-directional since a severe reduction of REM sleep – about 6% – has been observed among patients suffering delirium. REM sleep is the phase in which the brain carries out crucial processes for cognitive, emotional and social development,4,8,15,17 and given that children are in the midst of important neurological development, they are particularly vulnerable to the negative consequences of sleep disorders.15,17,22

In addition, the literature recognises a close relationship between sleep disorders, delirium and post-intensive care syndrome (PICS), characterised by a deterioration of one or more aspects among the physical, psychological, cognitive and/or social functioning, following discharge from a PICU.3,8,9,15,21

Although most research on morbidity and mortality of critically ill patients have been conducted among adults,8,15,16 an increase in the morbidity and mortality of critically ill children has also been identified, derived from the combination of sleep disorders, delirium and PICS.2,21 Morbidity manifests in the form of long-term alterations in memory, language, attention and mobility, with a particular prevalence of psychosocial morbidity, manifesting as depression, anxiety and posttraumatic stress, affecting 60% of critically ill children who suffered sleep disorders.8,21,23 Regarding the increase of mortality, studies conducted among adult patients indicate that sleep alterations have a prognostic value, since an abnormal sleep architecture increases the severity of encephalopathy and the lack of regularly alternating light-darkness periods enhances the worsening of sepsis.15,16 In addition, a study by Traube et al. concluded that the mortality of children in PICUs and diagnosed with delirium increased significantly from 0.94% to 5.24%.21

As previously indicated, one of the factors negatively affecting sleep are nocturnal interventions, including monitoring, administration of medication, feeding or posture changes.10,24 However, studies in this respect are scarce, and no clear relationship has been established between nursing interventions and rest interruption.10,25

The night should be a time of calm, with minimal healthcare interventions, especially between 11:00 pm and 7:00 am, although these times change depending on the literature consulted, based on sociocultural differences between countries.26–28 Moreover, Le et al. conclude that many nocturnal ICU interventions could be postponed with no harm for patients. They also indicate that, despite dedicating one third of their time to maintaining records, nursing staff do not always cover all care activities, observing that the use of standardised language increases the quality of such records.29

The application of standardised terminology makes it possible to identify, organise and document nursing staff actions. In addition, it makes it possible to recognise key interventions for different hospital environments. To this end, the use of standardised terminology would enable the creation of banks of interventions to facilitate planning.30,31

This work considers identification of night-time nursing interventions by following the Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC), which is one of the most widespread terminologies.

The relevance of this study is based on the significant repercussion of sleep disorders, the vulnerability of paediatric patients and the scarce evidence on the relationship between sleep alterations and nocturnal nursing interventions.

Therefore, the objective was to identify and analyse nursing interventions, following the NIC taxonomy, conducted between 11:00 pm and 7:00 am at PICUs in the National Healthcare System (SNS), and their relationship with the variables “level of care” and “hospital where the interventions were conducted”.

MethodDesign, environment, study periodA descriptive, horizontal and multi-centre study at SNS PICUs was conducted from May/2023 until February/2024.

The study environment were the 49 PICUs in the SNS, and participation was offered to all of them that the study had access to, which were a total of 14, distributed among 7 Spanish autonomous regions. Recruitment of centres was carried out through scientific societies, working networks and the support of the supervisory team at the coordinating centre.

Following the 4th Technical Report of the Spanish Society for Paediatric Intensive Care, which defined the levels of care at PICUs, the participation of level III (treats any paediatric patient) and level II PICUs (offers intensive treatment, but not for every speciality) was ensured. Level I units were excluded, since these are only prepared for the stabilisation and transfer of patients, with no overnight care.32

Study populationThe study population consisted of the records of nursing interventions conducted between 11:00 pm and 7:00 am among patients staying overnight at each PICU on the date in which the form was completed. A convenience sampling method was used, meaning that the records for interventions were requested for the first 10 patients admitted to each PICU after the collection phase began. A total of 10 records per hospital were obtained, based on similar studies in adult populations,10 since there were no precedents in paediatric populations.

Study variablesStudy variables were classified into 2 groups: one related to PICU characteristics and another related to interventions.

The first included hospital variables (identified via 01-10 coding), number of beds, structure of boxes (open/closed/mixed), level of care (level II/III) and existence of a sleep protocol (yes/no).

In the second group, the variables were: different NIC nursing interventions (understood as absolute frequency of different nursing interventions conducted) and total NIC nursing interventions (understood as absolute frequency of total nursing interventions conducted). The nursing interventions collected were those taking place between 11:00 pm and 7:00 am, based on the time schedule studied in other works.26,28

Data collectionA data collection form was designed ad hoc, via comprehensive reading of NIC 7th edition33 by the main researcher and 3 experts in critical care (nursing professionals with more than 5 years of experience at a PICU). As a result, 93 of the total 565 existing NIC were identified as specific to a PICU.

In order to facilitate data collection, the interventions were classified into: “feeding”, “comfort”, “general care”, “pain”, “elimination”, “emotional”, “hemodynamic”, “medication”, “sampling/venous access”, “neurological”, “renal”, “respiratory” and “urgent care”. Within each group, interventions were organised alphabetically and their definition was included.33 The number of repetitions per intervention was also incorporated: one time/2 times/3 or more.

The form was tested as a pilot among 10 patients at the promoting hospital, in order to verify its operability and identify any NIC that might not have been selected in the creation phase. From this pilot, a final version was established, excluding the data obtained from the analysis.

In parallel, the authors contacted PICUs to invite them to participate. Following acceptance, the collaborating nursing professional at each unit was sent the study protocol, filling instructions and data collection form, in print and electronic versions. The main researcher held at least a telephone conversation with each collaborator to explain the data collection methodology, seeking to avoid variability.

The time of data collection was established as after 7:00 h, once the observation period had concluded. Each collaborating nurse, based on the clinical history, collected the interventions applied to patients in their charge that night. The collection of interventions conducted on the same patient in subsequent days was rejected.

Data analysisThe analysis was conducted using the statistics program SPSS® v. 29. A sample distribution analysis was carried out, and based on this the quantitative data were expressed as mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range, as appropriate, while the qualitative data were expressed as percentages and frequency tables.

For the bivariate analysis, the variables “different NIC nursing interventions” and “total NIC nursing interventions” were operationalised. In the first analysis, interventions were grouped by level of care, to evaluate whether this affected the number of interventions performed. This was done by means of the Student’s t test.

The interventions were also grouped by “hospital”, in order to conduct an inter-hospital analysis of the variables “different NIC nursing interventions” and “total NIC nursing interventions”. To this end, a variance analysis (ANOVA) was applied.

In all cases, a level of P < .05 was interpreted as significant.

Ethical considerationsThe ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki were followed at all times.34 Since no identifying nor clinical data from patients or collaborating nursing staff were collected, the Ethics Committee of the promoting centre concluded that it was not necessary to carry out an approval process for the project or collect informed consent. In addition, authorisation was requested from the managers of each PICU to confirm their participation.

ResultsOut of the 14 PICUs contacted, 10 agreed to participate. Taking into account that the number of PICUs in the entire SNS is 49, the study obtained access to a 20.4% representation. In total, 60% (n = 6) of the participating PICUs had a level of care iii, with 80% (n = 8) maintaining a structure of closed boxes and 20% (n = 2) mixed. The range of beds per PICU were between 5 and 18 and none had a sleep protocol (Table 1).

Characteristics of participating PICUs.

| Hospital code | Number of beds | Box structure | Level of care | Sleep protocol |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HOSPITAL_01 | 18 | Closed | III | No |

| HOSPITAL_02 | 8 | Closed | III | No |

| HOSPITAL_03 | 10 | Closed | II | No |

| HOSPITAL_04 | 5 | Closed | II | No |

| HOSPITAL_05 | 17 | Mixed | III | No |

| HOSPITAL_06 | 5 | Closed | II | No |

| HOSPITAL_07 | 13 | Closed | III | No |

| HOSPITAL_08 | 8 | Mixed | III | No |

| HOSPITAL_09 | 12 | Closed | III | No |

| HOSPITAL_10 | 4 | Closed | II | No |

A total of 100 records were collected, with 87 different nursing interventions identified and a total frequency of 5.017.

The only intervention identified in 100% (n = 100) of records was “monitoring of vital signs”, followed by “environmental management” and “improving sleep”, present in 98 (n = 98) and 94% (n = 94), respectively (Table 2).

Different NIC nursing interventions identified most commonly in the records.

| Nursing intervention label (NIC taxonomy) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Vital signs monitoring | 100 (100) |

| Environmental management | 98 (98) |

| Sleep enhancement | 94 (94) |

| Medication administration: intravenous | 90 (90) |

| Fluid monitoring | 78 (78) |

| Skin surveillance | 74 (74) |

| Perineal care | 73 (73) |

| Respiratory monitoring | 71 (71) |

| Bedridden patient care | 68 (68) |

| Pressure ulcer prevention | 68 (68) |

| Anxiety reduction | 66 (66) |

| Fall prevention | 64 (64) |

| Emotional support | 52 (52) |

| Pain management: acute | 48 (48) |

| Airway management | 47 (47) |

| Airway suctioning | 45 (45) |

| Relaxation technique | 44 (44) |

| Neurological monitoring | 44 (44) |

| Enteral tube feeding | 42 (42) |

| Skin care: topical treatment | 41 (41) |

| Eye dryness prevention | 41 (41) |

| Fluid/electrolyte management | 41 (41) |

| Sedation management | 40 (40) |

| Massage | 40 (40) |

The most frequent interventions, in other words, the most commonly repeated in the records, were “monitoring of vital signs”, conducted in 290 occasions, “environmental management”, in 236, and “administration of medication: intravenous”, conducted 234 times (Table 3).

Total NIC nursing interventions conducted.

| Nursing intervention label (NIC taxonomy) | Total NIC nursing interventions (%) |

|---|---|

| Vital signs monitoring | 290 (5.78) |

| Environmental management | 236 (4.69) |

| Medication administration: intravenous | 234 (4.66) |

| Sleep enhancement | 202 (4.02) |

| Respiratory monitoring | 187 (3.72) |

| Fluid monitoring | 174 (3.46) |

| Perineal care | 169 (3.36) |

| Pressure ulcer prevention | 164 (3.26) |

| Bedridden patient care | 158 (3.14) |

| Anxiety reduction | 151 (3.00) |

| Fall prevention | 151 (3.00) |

| Skin surveillance | 139 (2.77) |

| Emotional support | 119 (2.37) |

| Airway management | 116 (2.31) |

| Enteral tube feeding | 107 (2.13) |

| Neurological monitoring | 106 (2.11) |

| Relaxation technique | 103 (2.05) |

| Sedation management | 94 (1.87) |

| Pain management: acute | 91 (1.81) |

| Fluid/electrolyte management | 88 (1.75) |

| Urinary catheter care | 87 (1.73) |

| Airway suctioning | 85 (1.69) |

| Skin care: topical treatment | 85 (1.69) |

| Massage | 83 (1.65) |

| Invasive haemodynamic monitoring | 81 (1.61) |

Grouping interventions by level of care, the mean number of different NIC nursing interventions at level ii PICUs was 20.87 ± 7.41, and that at level iii PICUs was 24.42 ± 7.55. Regarding the total number of NIC nursing interventions, also grouped by level of care, the mean number at level ii PICUs was 50.68 ± 19.20 and at level iii PICUSs was 49.83 ± 19.48.

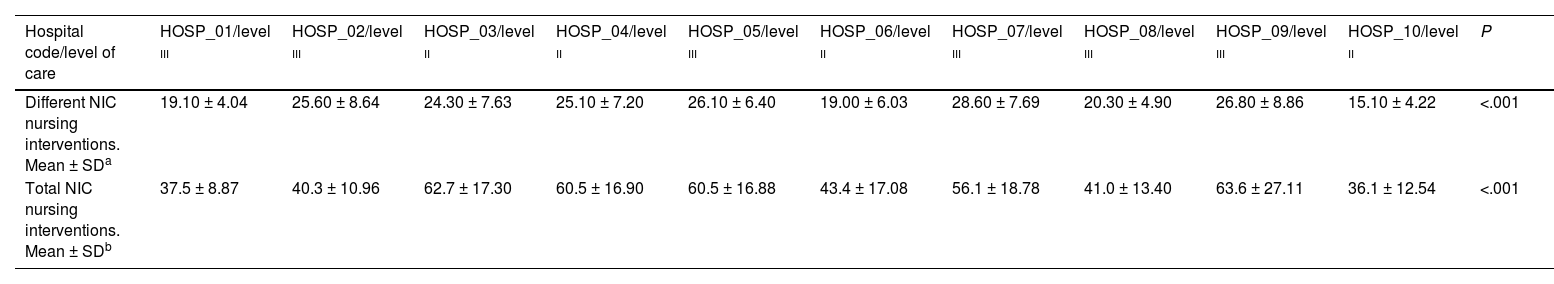

In relation to the grouping of interventions by hospital, in the one registering the most, the mean number of different NIC nursing interventions was 28.60 ± 7.69, and in the one registering the least, it was 15.10 ± 4.22. Regarding the mean total NIC nursing interventions also grouped by hospital, in the centre registering the most the mean number was 63.6 ± 27.11, while in the centre registering the least, the mean number was 36.1 ± 12.54 (Table 4).

The bivariate analysis found no significant differences when comparing the mean number of different NIC nursing interventions (P = .861) and the mean number of total NIC nursing interventions (P = .069) with the level of care. However, statistically significant results were observed when comparing the variable hospital with the mean number of different NIC interventions and the mean number of total NIC interventions (P < .001) (Table 4).

Bivariate analysis. Association between the variables “different NIC nursing interventions” and “hospital,” and the variables “total NIC nursing interventions” and “hospital”.

| Hospital code/level of care | HOSP_01/level iii | HOSP_02/level iii | HOSP_03/level ii | HOSP_04/level ii | HOSP_05/level iii | HOSP_06/level ii | HOSP_07/level iii | HOSP_08/level iii | HOSP_09/level iii | HOSP_10/level ii | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Different NIC nursing interventions. Mean ± SDa | 19.10 ± 4.04 | 25.60 ± 8.64 | 24.30 ± 7.63 | 25.10 ± 7.20 | 26.10 ± 6.40 | 19.00 ± 6.03 | 28.60 ± 7.69 | 20.30 ± 4.90 | 26.80 ± 8.86 | 15.10 ± 4.22 | <.001 |

| Total NIC nursing interventions. Mean ± SDb | 37.5 ± 8.87 | 40.3 ± 10.96 | 62.7 ± 17.30 | 60.5 ± 16.90 | 60.5 ± 16.88 | 43.4 ± 17.08 | 56.1 ± 18.78 | 41.0 ± 13.40 | 63.6 ± 27.11 | 36.1 ± 12.54 | <.001 |

The results obtained coincide with other similar results obtained in the context of adult critically ill patients, with “monitoring of vital signs” being the most frequent intervention.10 There are studies in this regard, such as that by Yoder et al., as well as more recent ones, such as that of Najafi et al., indicating that the frequent monitoring of vital signs during the night could be avoided by identifying patients considered stable.35,36 In fact, the number of occasions on which vital signs are monitored in stable patients is similar to that collected in at risk patients.36,37 Other very frequent interventions included “administration of medication”, “airway management” and “neurological monitoring,” which coincided with other studies.10

Regarding interventions related to rest, “improving sleep” was present in over 90% of records, in contrast with the literature, which makes no reference to interventions connected to rest.10

None of the participating PICUs had a protocol regulating the crucial aspects to ensure quality of sleep among critically ill children. Nevertheless, the evidence concludes that, when these types of protocols contemplate the planning of care, their application in ICUs can decrease the number of interventions, which would entail a benefit for patients by reducing rest interruptions.10,20,38 In fact, Dean et al. identified that the percentage of critically ill children who did not suffer rest interruptions increased from 32% to 49% following the application of a sleep protocol.38 Along the same line, Knauert et al. concluded that, after applying an ICU sleep protocol, the percentage of nocturnal nursing interventions decreased to 32%.39 Among the recommendations for the design of these protocols, it is worth highlighting their development based on a bundle including environmental light and noise control, nocturnal nursing activities, pharmacological measures and prevention of delirium.15,40

In terms of the possibility of advancing/delaying or even omitting night-time interventions, the evidence indicates that many interventions are based on the time scheduling of healthcare professionals, as part of working routines.10,27,29,36,38 This could coincide with one of the key findings in the present study: the hospital where care is provided has an impact on the frequency of nocturnal interventions conducted, that is, the working routine of each hospital could have affected the NIC nursing interventions conducted and the total number thereof.

Lastly, regarding the total NIC nursing interventions, it could be assumed that there should be a higher number of interventions at level iii PICUs, due to the greater complexity of the patients treated. Despite this assumption, the present study did not find significant differences. Given that the classification of care level is a particularity of the Spanish SNS, this result could not be compared internationally. Nevertheless, the available literature did identify a correlation between the severity of patients and a higher number of nursing interventions conducted.10,18

Limitations and strengthsThe lack of evidence in the identification of PICU nursing interventions represented a handicap. Moreover, there were other standardised languages, such as the ATIC terminology, which could have negatively affected the bibliographic search.

Another limitation was the number of participating PICUs. Nevertheless, the study included PICUs with different characteristics, which could be a starting point for similar studies.

It is also worth noting that the data collection form was not validated and there could have been a certain Hawthorne effect when collecting the interventions conducted by the collaborating nursing professionals themselves.

In addition, days of admission were not collected as a variable, which could have influenced the number of interventions, assuming that these could be more numerous during the first days. Neither were sociodemographic nor clinical variables collected, which prevented a comparison between records. The exact schedule of each intervention was not collected either, which could have identified periods without rest interruptions.

As a strength, this study represents a starting point for debate and critical reflection about the organisation of night-time care activities and the potential negative effect they could have on the rest of critically ill children. In addition, it could promote the development of sleep protocols.

ConclusionsThe NIC taxonomy was used to identify the nursing interventions conducted most frequently at a PICU, with the most common intervention being “monitoring of vital signs” followed by “environmental management”.

Although none of the units had a sleep protocol, the majority of records collected some intervention to improve rest.

No significant differences were found between the level of care of each PICU and nursing interventions. Differences were found between hospitals.

Ethical considerations and informed consentThe study was conducted following the ethical principles and the Declaration of Helsinki. After consultation with the relevant Ethics Committee, since no patient identifying data were found, the collection of informed consent was not considered necessary. In addition, the managers of each PICU were asked for authorisation to confirm their participation.

FinancingThis study was financed through the 2022 Dr. Luis Álvarez Biomedical Research grant for Emerging or Associated Clinical Groups, from the Healthcare Research Institute of La Paz University Hospital (IdiPAZ).

This study received financial support from the Healthcare Research Institute of La Paz University Hospital (IdiPAZ) through the 2022 Dr. Luis Álvarez Biomedical Research grant for Emerging or Associated Clinical Groups.

The research team wish to explicitly thank the Healthcare Research Institute of La Paz University Hospital (IdiPAZ) for the financial support received. In addition, the main researcher wishes to thank the nursing teams of the participating SNS PICUs for their collaboration in data collection.