The aim of this study was to develop and validate the adaptation of the behavioural indicators of pain scale (ESCID) for patients with acquired brain injury (ESCID-DC), unable to self-report and with artificial airway.

MethodsMulticenter study conducted in 2 phases: scale development and evaluation of psychometric properties. Two blinded observers simultaneously assessed pain behaviours with two scales: ESCID-DC and Nociception Coma Scale-Revised version-adapted for Intubated patients (NCS-R-I). Assessments were performed at 3 time points: 5 min before, during and 15 min after the application of the painfull procedures (tracheal suction and application of pressure to the right and left nail bed) and a non-painful procedure (rubbing with gauze). On the day of measurement, the Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) and the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS) were evaluated. A descriptive and psychometric analysis was performed.

ResultsA total of 4152 pain evaluations were performed in 346 patients, 70% men with a mean age of 56 years (SD = 16.4). The most frequent etiologies of brain damage were vascular 155 (44.8%) and traumatic 144 (41.6%). The median GCS and RASS on the day of evaluation were 8.50 (IQR = 7 to 9) and −2 (RIQ = −3 to −2) respectively. In ESCID-DC the median score was 6 (IQR = 4 to 7) during suction, 3 (RIQ = 1 to 4) for right pressure and 3 (RIQ = 1 to 5) for left pressure. During the non-painful procedure it was 0. The ESCID-DC showed a high discrimination capacity between painful and non-painful procedures (AUC > 0.83) and is sensitive to change depending on the time of application of the scale. High interobserver agreement (Kappa > 0.87), good internal consistency during procedures (α-Cronbach≥0.80) and a high correlation between the ESCID-DC and the NCS-R-I (r ≥ 0.75) were obtained.

ConclusionsThe results of this study demonstrate that the ESCID-DC is a valid and reliable tool for assessing pain in patients with acquired brain injury, unable to self-report and with artificial airway.

El objetivo de este estudio fue desarrollar y validar la adaptación de la Escala de Conductas Indicadoras de Dolor (ESCID) para pacientes con daño cerebral adquirido (ESCID-DC), incapaces de autoinformar y con vía aérea artificial.

MétodoEstudio multicéntrico realizado en 2 fases: desarrollo de la escala y evaluación de las propiedades psicométricas. Dos observadores cegados evaluaron simultáneamente las conductas dolorosas con dos escalas: ESCID-DC y Nociception Coma Scale-Revised version—adapted for Intubated patients (NCS-R-I). Las evaluaciones se realizaron en 3 momentos: 5 minutos antes, durante y 15 minutos después de la aplicación de procedimientos dolorosos (aspiración de secreciones y presión derecha e izquierda) y un procedimiento no doloroso (roce con gasa). El día de medición se valoró el nivel Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) y Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS). Se realizó un análisis descriptivo y psicométrico.

ResultadosSe realizaron 4152 evaluaciones de dolor en 346 pacientes, el 70% hombres con edad media de 56 años (DE = 16,4). Las etiologías de daño cerebral más frecuentes fueron la vascular 155 (44,8%) y traumática 144 (41,6%). La mediana de GCS y RASS el día de evaluación fue 8,50 (RIQ = 7 a 9) y -2 (RIQ=-3 a -2) respectivamente. En ESCID-DC la puntuación mediana fue de 6 (RIQ = 4 a 7) durante la aspiración, de 3 (RIQ = 1 a 4) para la presión derecha y de 3 (RIQ = 1 a 5) para la presión izquierda. Durante el procedimiento no doloroso fue 0. ESCID-DC mostró una alta capacidad de discriminación entre procedimientos dolorosos vs no doloroso (AUC > 0,83) y es sensible al cambio en función del momento de aplicación de la escala. Se obtuvo una alta concordancia interobservador (Kappa>0,87), una buena consistencia interna durante los procedimientos (α-Cronbach≥0,80) y una correlación alta entre ESCID-DC y NCS-R-I (r ≥ 0,75).

ConclusionesLos resultados de este estudio muestran que ESCID-DC es una herramienta válida y fiable para evaluar el dolor en pacientes con daño cerebral adquirido, incapaces de autoinformar y vía aérea artificial.

It is recommended that pain assessment in critically ill patients who are unable to self-report be performed using behavioural scales. Behavioural Indicators of Pain Scale (ESCID) is a validated tool in critically ill medical and post-surgical patients who are unable to self-report and undergoing mechanical ventilation. However, experts recommend validating these tools in critically ill patients with brain injury and disorders of consciousness.

What is the contribution of this?In this article, the ESCID is developed and validated in patients with brain injury (ESCID-DC) and disorders of consciousness. The results demonstrate the good psychometric properties of this tool, which enable its use to assess pain in this vulnerable population of critically ill patients.

Implications of the studyAccording to the results obtained, applying ESCID-DC will enable pain monitoring in patients with brain injury and disorders of consciousness admitted to the ICU. As a result, pharmacological or non-pharmacological interventions can be planned to prevent or reduce pain.

Despite advances in monitoring and treatment, pain remains a common experience in patients unable to self-report admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU). Prevalence data for pain are estimated at 43%, which can vary depending on the time of assessment from 33% at rest to 90% during painful procedures.1,2 Causes related to pain in critically ill patients include injuries or illness and the resulting complications, as well as procedures related to treatment.3–5 Uncontrolled pain is a source of stress and can compromise patient recovery in terms of adverse events such as agitation and delirium, increased hospital stay or chronic pain.6–8

The recommendation for pain assessment in critically ill patients unable to self-report is the use of behavioural scales.9,10 In Spain, the Behavioural Indicators of Pain Scale (ESCID for its initials in Spanish) is available, designed and validated by Latorre-Marco et al. al.11,12 It includes 5 behavioural indicators that score from 0 to 2 (facial expression, calmness, muscle tone, compliance with mechanical ventilation, and consolability), with an overall score range of 0 to –10. ESCID was validated primarily in critically ill medical and post-surgical patients, unable to self-report and undergoing mechanical ventilation. The psychometric properties showed that it is a valid and reliable scale, presenting a high correlation between ESCID and the Behavoiral Pain Scale (r = 0.94–0.99; p < 0.001), good internal consistency ((α-Cronbach 0.85; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.81 to –0.88) and high inter-intra-observer agreement.

The application of ESCID in patients with traumatic brain injury and disorders of consciousness showed an increase in the scale score during the performance of a painful procedure, compared to the baseline and after its performance and also with a non-painful procedure. However, the pain score was lower in patients with a low level of consciousness, compared to patients with a higher level of consciousness, despite applying the same painful procedure. This indicated that the level of consciousness influenced and/or limited the behavioural response. In addition, in this type of patients, different behavioural responses were recorded to the indicators collected by the ESCID scale, such as opening the eyes, blinking, opening the mouth/yawning and making sucking movements.13

The validation of behavioural pain scales in critical patients with brain injury and disorders of consciousness could improve their applicability and ability to detect pain more accurately, which is one of the directions towards which future research should be directed.14–16

The aim of this study was to develop and psychometrically validate the adaptation of the Behavioural Indicators of Pain Scale (ESCID) for patients with acquired brain injury (ESCID-DC), unable to self-report and with artificial airway.

MethodThis study consisted of two phases: 1) development of the ESCID-DC content, and 2) evaluation of the psychometric properties of ESCID-DC, following the COSMIN17.

methodological principles and terminology.

Phase 1. Development of the ESCID-DC contentThis phase was carried out in three stages, each with a different method.

Stage oneThe objective was to identify the essential behavioural indicators to evaluate pain in critically ill patients with brain injury, disorders of consciousness, unable to self-report and with artificial airway. For this purpose, a prospective observational study was carried out in this type of patients, in which video recordings were made to capture facial and body behavioural responses under different conditions (rest and during painful procedures vs. non-painful procedures). Each video recording was then viewed and analysed by three expert evaluators who were blinded to each other. The experts had ≥10 years of experience in the care of patients with brain injury and extensive experience in the application of ESCID. The result was 33 behaviours: 29 considered active behaviours and 4 neutral behaviours. The 29 active behaviours were grouped into three blocks: facial, body and ventilation-related. In addition, the characteristic ESCID item called comfort was added. The final result was a list of 30 behavioural indicators.18

Stage twoThe objective was to evaluate the content validity of the 30 behavioural indicators using the Delphi technique with a panel of experts. The experts belonged to different professions (medicine, nursing and psychology), had ≥10 years of experience in the care of patients with brain injury and 70% were doctors with lines of research related to pain in non-communicative critical patients and/or in the validation of behavioural scales. An online questionnaire was created on the Limesurvey® platform where each expert scored the different behavioural indicators under the criteria of relevance, pertinence, clarity and usefulness through a 5-point Likert scale (1 = totally disagree; 5 = totally agree).

The content validity of each behavioural indicator was calculated from the percentage of experts who assigned a score of 4 or 5. According to the criteria of Polit and Beck,19 behavioural indicators with a result ≥ 0.78 were integrated into the scale.

Five rounds were carried out, resulting in 10 behavioural indicators as the final result.

Stage threeA face validity test of the scale was carried out following Grimm’s20 recommendations. Thirty-one active nurses participated, all of whom had experience in the application of behavioural pain scales in their clinical practice and care for patients with the same characteristics as the population to which the scale was directed. They had to evaluate the 10 behavioural indicators in terms of their written expression and comprehensibility. The time required and the ease of scoring each category of the behavioural indicators of the scale were also evaluated. This led to clarification of the item categories in the ESCID-DC user guide. The time required to complete the scale scoring ranged from 1−3 min.

Phase 2. Evaluation of ESCID-DC’s psychometric propertiesDesignProspective, observational, multicentre study with psychometric validation.

Subjects and settingInclusion criteria were: age ≥ 16 years; acquired brain injury (of varying aetiology); unable to self-report (verbal or motor); artificial airway, and signed consent. Exclusion criteria were: previous pathology of injury and/or cognitive impairment; spinal cord injury; severe polyneuropathy; diagnosis of brain death; continuous infusion of muscle relaxants; barbiturate coma; deep sedation level (Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale = –5) and Glasgow Coma Scale score = 3.

The study was conducted in 21 ICUs in 17 hospitals of the Spanish National Health System where patients with acquired brain injury in the acute phase are treated. The 21 ICUs corresponded to 16 (76%) multipurpose units and 5 (24%) neuro-trauma units. The 17 participating hospitals were located in the following autonomous communities: Community of Madrid with 6 (35%), Catalonia with 4 (23%) and Galicia, Principality of Asturias, Aragon, Andalusia, Balearic Islands, Foral Community of Navarre and Castilla-La Mancha with one hospital each.

SampleThe sample size was calculated according to the recommendation of Streiner and Kottner21 taking into account several criteria: 1) given the heterogeneity of patients with brain injury, it was intended to represent the two main aetiologies: traumatic and vascular, with a minimum of 10–20 participants for each item on the scale, and 2) a sample of 200–300 participants to be able to perform factor analysis. A minimum sample of 300 patients guaranteed the two criteria.

Recruitment was carried out consecutively ensuring that the inclusion criteria were met.

Training of the researchersEach participating centre had a coordinator and a research team composed of nurses who care for critically ill patients with brain injury. Each research team received a standardised training session and a training period consisting of the evaluation of a minimum of 5 patients per centre to apply ESCID-DC. Feedback was given on each evaluation, especially when there were discrepancies in the scores between evaluators, reinforcing the instructions in the ESCID-DC user guide. The training phase lasted approximately one month. During the training period, 90 patients were evaluated, who were not included in the study sample.

Data collection procedureMain response was assessed by two independent observers, blinded to each other, at three times: before, during, and 15 min after performing different procedures (painful vs. non-painful).

The painful procedures selected were tracheal suction and pressure application to the nail bed of the ring finger or, if this was not possible, to the nail bed of the middle finger, in both upper limbs. Pressure was applied with the Algiscan plus® algometer, applying a pressure range of 5 to –8 kg until a behavioural response was obtained or for a maximum time of 30 s. The non-painful procedure, established as a control element, consisted of rubbing a portion of healthy skin tissue on the patient's forearm with gauze, or, if this was not possible, on the calf. Each of the procedures was applied to all patients and a 15 min washout period was guaranteed between procedures.

Once all the information was collected, the results obtained for each of the 10 items that made up the initial version of the scale were explored. It was observed that two of these items showed scores greater than 0 in only 13% of the patients. In addition, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test for these two items took values below 0.6, and therefore they were eliminated from the scale. The final version of the ESCID-DC scale was composed of 8 items.

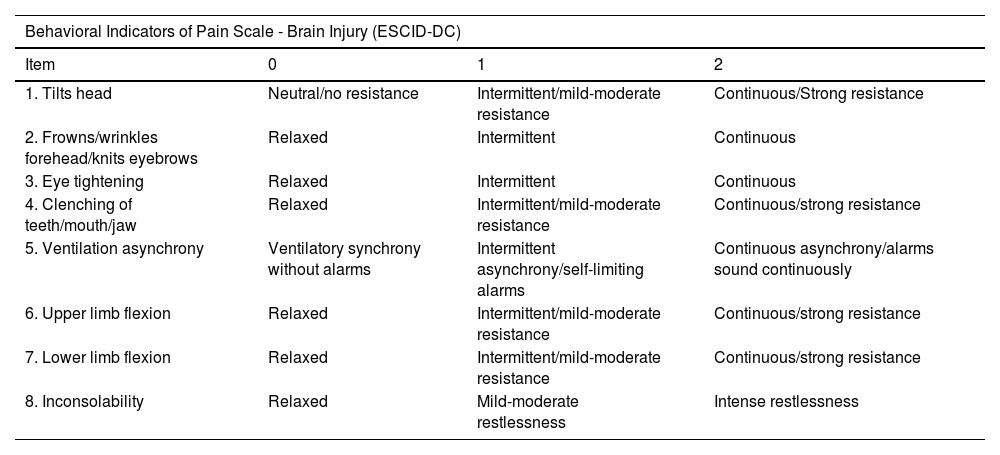

Tools and variablesFor the evaluation of the pain response, the ESCID-DC scale and the Nociception Coma Scale-Revised-adapted for Intubated patients (NCS-R-I),22 scale were used, which was taken as a reference. The scales are shown in Table 1.

Pain assessment scales.

| Behavioral Indicators of Pain Scale - Brain Injury (ESCID-DC) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Item | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| 1. Tilts head | Neutral/no resistance | Intermittent/mild-moderate resistance | Continuous/Strong resistance |

| 2. Frowns/wrinkles forehead/knits eyebrows | Relaxed | Intermittent | Continuous |

| 3. Eye tightening | Relaxed | Intermittent | Continuous |

| 4. Clenching of teeth/mouth/jaw | Relaxed | Intermittent/mild-moderate resistance | Continuous/strong resistance |

| 5. Ventilation asynchrony | Ventilatory synchrony without alarms | Intermittent asynchrony/self-limiting alarms | Continuous asynchrony/alarms sound continuously |

| 6. Upper limb flexion | Relaxed | Intermittent/mild-moderate resistance | Continuous/strong resistance |

| 7. Lower limb flexion | Relaxed | Intermittent/mild-moderate resistance | Continuous/strong resistance |

| 8. Inconsolability | Relaxed | Mild-moderate restlessness | Intense restlessness |

| Nociception Coma Scale-Revised-adapted for Intubated patients (NCS-R-I) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Motor response | None | Abnormal posture | Flexion withdrawal | Localisation to painful stimulation |

| Compliance with ventilation | Tolerating ventilation | Coughing but tolerating ventilation most of the time | Fighting ventilator but ventilation possible sometimes | Unable to control ventilation |

| Facial expression | None | Oral reflexive movement/startle response | Grimace | Crying |

ESCID-DC includes 8 items grouped into facial response, ventilation/respiration, body response and inconsolability, with a score range for each of the items from 0 to 2. The total score of the scale is from 0 to 16.

NCS-R-I includes 3 items: motor response, compliance with ventilation and facial expression, with a score range for each of the items from 0 to 3. The total score of the scale is from 0 to 9. This scale was the first tool validated specifically to evaluate pain in patients with brain injury. The authors’ permission was obtained beforehand and the process of translation/back-translation and validation into Spanish was carried out. The psychometric properties of the Spanish translation of NCS-R-I showed that it is a valid and reliable scale, presenting good internal consistency (ordinal alpha between 0.60 and 0.90) and high interobserver agreement (kappa >0.80; intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) >0.90). Discriminant validity reached an AUC of 0.952.

On the day of measurement, the level of consciousness (Glasgow Coma Score [GCS]) and the level of sedation (Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale [RASS]) were documented in the patients, and the therapeutic regimen of analgesia and sedation administered continuously and discontinuously was recorded.

Sociodemographic variables, personal history, severity indicators, variables related to neurological pathology, variables related to mechanical ventilation and artificial airway, and finally, ICU-related variables (duration of stay and mortality).

Statistical analysisA descriptive analysis of demographic, clinical, and scale characteristics was performed.

The reliability of ESCID-DC was analysed by internal consistency using the α-Cronbach and its 95% CI for each assessment time and procedure. The extent to which internal consistency would improve (or worsen) by eliminating each item was also evaluated.

The agreement between the two observers was assessed with the kappa coefficient and its 95% CI for each ESCID-DC item. The ICC and its 95% CI were also calculated for the total score of the scale.

The construct validity of ESCID-DC was examined based on the results obtained during the application of painful procedures. The total sample was randomly divided into two subsamples. The first represented 70% of the total and was used to obtain the factor solution (exploratory factor analysis). The second, the remaining 30%, was used to validate the results through a confirmatory factor analysis, calculating the goodness-of-fit index (GFI), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Both factor analyses were based on the polychoric correlation matrix using the weighted least squares method. The exploratory factor analysis was obtained using the fa function of the psych package; to perform the confirmatory factor analysis and obtain the different adjustment measures, the cfa function of the lavaan package was used.

The discriminant validity between painful vs. non-painful procedures was evaluated using the area under the AUC curve. Convergent validity was studied using the Pearson correlation coefficient between ESCID-DC and NCS-R-I.

Finally, to analyse the sensitivity to change at the different times of application of ESCID-DC, a mixed model was used, also adjusting for the different procedures and observers.

The significance value was set at α = 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using R software version 4.3.3.23

Ethical considerationsThe study was approved by the ethics committee of the reference hospital (CEIm 20/483) and by the ethics committees or feasibility commissions of the participating centres. This research was conducted in accordance with Spanish and European Union legislation on data management and confidentiality. Written consent was obtained from the relatives/representatives of all included patients.

ResultsThe psychometric properties of ESCID-DC were analysed in a sample of 346 critically ill patients with brain injury and disorders of consciousness, unable to self-report, and with artificial airway. The flow chart is shown in Fig. 1.

Patient characteristicsPatient characteristics are described in Table 2. Seventy percent of the sample was male, and the mean age was 56 (SD: 16.4) years. The main aetiology of brain injury was vascular (155 [44.8%]) and trauma (144 [41.6%]), with neurosurgery required in almost 45% of patients. On the day of assessment, the level of consciousness was low (GCS ≤ 9), with focal neurological signs observed in 169 (48.9%) patients. The level of sedation was moderate-light RASS –2 (RIQ: –3, –2). Opioids were the most frequent analgesics administered by continuous infusion (255 [65%]) and paracetamol by discontinuous regimen (137 [39.6%]).

Patients characteristics (n = 346).

| Sex, n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Men | 239 (69.1%) |

| Women | 107 (30.9%) |

| Age, M (SD) years | 56.03 (16.41) |

| Personal history, n (%) | |

| Chronic pain | 31 (9%) |

| Chronic analgesic use | 34 (9.8%) |

| Substance abuse | 56 (16.5%) |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 44 (13%) |

| Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS) II, Md (IQR) | 49 (37−61) |

| Acquired brain injury aetiology, n (%) | |

| Traumatic | 144 (41.6%) |

| Vascular | 155 (44.8%) |

| Others | 47 (13.6%) |

| Brain damage, n (%) | |

| Focal/Multifocal | 298 (86.1%) |

| Diffuse | 48 (13.9%) |

| Neurological focality, n (%) | |

| Yes | 169 (48.9%) |

| No | 177 (51.2%) |

| Neurosurgery, n (%) | |

| Yes | 156 (45.1%) |

| No | 190 (54.9%) |

| Artificial airway, n (%) | |

| Oral endotracheal tube | 287 (82.9%) |

| Tracheostomy tube | 59 (17%) |

| Ventilator support, n (%) | |

| Totally controlled | 149 (43.1%) |

| Partial support | 181 (52.3%) |

| Spontaneous | 16 (4.6%) |

| Glasgow Coma Scale, Md (RIQ) | 8.50 (7−9) |

| Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale, Md (RIQ) | –2 (–3, –2) |

| Continuous intravenous infusiona, n (%) | |

| Fentanyl | 91 (26.3) |

| Morphine | 81 (23.4) |

| Remifentanil | 53 (15.31) |

| Propofol | 117 (33.8) |

| Midazolam | 16 (4.6%) |

| Dexmedetomidine | 40 (11.5) |

| Intravenous push infusionb, M (DE) | |

| Fentanyl | 28 (8) |

| Paracetamol | 137 (39.6) |

| Metamizole | 73 (21) |

| Dexketoprofen | 19 (5.5) |

| Midazolam | 14 (4) |

| Pre-procedural preventive analgesia, n (%) | |

| <1 h before | 55 (15.9) |

| 1–8 h before | 202 (58.3) |

| Days between ICU admission and enrolment, Md (IQR) | 7 (3−13) |

| Days in ICU, Md (IQR) | 21.50 (12−33.25) |

| ICU mortality, n (%) | 36 (10.4%) |

ICU: intensive care unit; M (SD): mean and standard deviation; Md (IQR): median and interquartile range.

Fig. 2 describes the ESCID-DC score under the different measurement conditions. During the performance of the painful procedures, the pain score increased, corresponding to a median total score of 6 (IQR: 4 to 7) for secretion aspiration, 3 (IQR: 1 to 4) for right pressure, and 3 (IQR: 1 to 5) for left pressure. Before and after, and in the non-painful procedure, the median total score was 0.

Fig. 3 shows the frequency of each ESCID-DC item during the painful procedures. It was found that item 8 or Inconsolability was the most frequent during both painful procedures. In the tracheal suction, item 5 or ventilator asynchrony stood out with a percentage difference >62% in relation to the pressure procedures. Item 6 or upper limb flexion was the most frequent behavioural response (>57%) in pressure procedures.

Internal consistencyThe internal consistency of the ESCID-DC scale showed a good α-Cronbach during the performance of painful procedures, with values ≥ 0.80.

Interobserver agreementInterobserver agreement during painful procedures obtained excellent results, with kappa values > 0.87 for all ESCID-DC items. The ICC also showed very high values in the different procedures and moments, with ICC values> 0.95 for the total score of the scale.

Construct validityThe polychoric correlation matrix showed that all items had a high correlation with at least 2 items of the scale. The KMO values (> 0.78) and the Barlett test (p = 0.001) indicated the viability of the factor analysis in the three cases.

Three-factor models were obtained in all procedures, with values of the GFI and TLI indices greater than 0.9, and the RMSEA close to 0 (Table 3 and Appendix B figures of the Supplementary material).

Factor extraction for the different painful procedures.

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tacheal suctiona | Upper facial expressions: Frowns/wrinkles forehead/knits eyebrows and eye tightening | Tilts head, lower facial expressions, and ventilator asynchrony Inconsolability | Flexion of upper and lower limbs |

| Right pressureb | Tilts head, flexes upper and lower limbs and Inconsolability | Upper facial expressions: rowns/wrinkles forehead/knits eyebrows and eye tightening | Lower facial expressions: clenching of teeth/mouth /jaw |

| Left pressurec | Tilts head, flexes upper and lower limbs and Inconsolability | Upper facial expressions: rowns/wrinkles forehead/knits eyebrows and eye tightening | Lower facial expressions: clenching of teeth/mouth /jaw |

GFI: goodness-of-fit index; RMSEA: root mean square error of approximation; TLI: Tucker-Lewis index.

b,cItem 5 had a very low factor loading for the 3 factors of the pressure procedures.

Fig. 4 shows the ROC curve and the AUC value on the ESCID-DC scale during the different painful procedures vs. non-painful procedures.

Convergent validityThe correlation between the ESCID-DC and NCS-R-I scores showed Pearson’s Rho correlation coefficient values r ≥ 0.75, all of which were significant (p < 0.001).

Sensitivity to changeThe multivariate model showed that pain scores for the secretion aspiration procedure were significantly higher than for the other procedures (p < 0.001). Scores for pressure procedures (right and left) did not differ between them. As expected, the painless procedure had the lowest scores (p = 0.001). Finally, it was also found that, regardless of the procedure, scores were significantly higher during its application (p < 0.001) (Fig. 2).

DiscussionThis study enabled the ESCID to be adapted and validated for a vulnerable ICU population. One aspect worth highlighting was the sample size and characteristics: it consisted of 346 patients with acquired brain injury of different aetiology and low level of consciousness (GCS ≤ 9), in the acute phase of admission to different ICUs in Spain. In addition, behavioural responses were collected under ideal conditions according to the experts' recommendations, with a sedation level RASS ≥ –3.9,10

The ESCID-DC scale showed good psychometric properties, comparable to those of the original ESCID scale12, the NCS-R-I22 reference tool and the Critical-Care Pain Observation Tool-Neuro (CPOT-Neuro)24 recently validated for patients with brain injury. As an exception, internal consistency values were higher in ESCID-DC vs NCS-R-I22 ((α-Cronbach ≥ 0.80 vs < 0.70) and ICC values were also higher in ESCID-DC vs CPO-Neuro24 (ICC > 0.95 vs 0.70–0.75). This last aspect is relevant, because in both studies scale usage training was made and this is probably related to the heterogeneity of procedures evaluated with CPOT- Neuro24 (more than 15 procedures) compared to those evaluated with ESCID-DC (3 procedures).

The modifications made to the ESCID-DC development process facilitated a better representation of the behavioural responses of the brain-injured patient in the ICU. Among the main characteristics, the evaluation of facial expression was emphasized with the incorporation of 3 items, and a higher score frequency was observed with respect to the facial musculature item of the original version of ESCID12, especially the two behaviours of the upper part of the face. This finding was also shared by Gélinas et al.24 in CPOT-Neuro. The ventilation asynchrony item of ESCID-DC focused the observation on the patient’s respiratory pattern, thus allowing the assessment of patients with artificial airway without connection to mechanical ventilation. The characteristic consolability item of ESCID12 was renamed Inconsolability. On the other hand, some behaviours were eliminated from the original version of the scale, such as muscle rigidity, a criterion that was also implemented by Gélinas et al.24 in CPOT-Neuro. This is a behaviour that previous research has shown to be expressed less frequently in this group of patients and can be confused with spasticity or brain injury itself.13,25,26 Coughing was also eliminated as a pain-indicating behaviour.

Regarding the procedures, it can be observed how the distribution of behavioural responses varies in the tracheal suction vs. pressure. There is also a slight discrepancy in the ESCID-DC score during pressure on both sides of the body, despite not finding significant differences, with the level of pain being greater on the left side. These differences were confirmed in the factor analysis, observing that the items were not grouped exactly the same. This could be justified because the type of procedure influences the behaviours that the patient manifests and by the presence of focal neurological signs in 169 (48.9) patients in the study. The latter is a notable criterion to take into account in the evaluation of pain, assuming the presence of pain in procedures documented as painful in the absence of behaviours.10

This study presents relevant results and allows clinicians to have a more precise tool to evaluate pain in this group of patients. In future research, it would be interesting to replicate the psychometric properties in other settings and with a wider range of procedures, as well as to evaluate the impact of implementing ESCID-DC in monitoring and treating pain in the acute phase of this population.

Limitations include not being able to analyse criterion validity due to the lack of a gold standard or the patient self-reporting obtained, due to the low level of awareness of the sample. The impact of analgesia on the scale procedures and scores was also not evaluated.

ConclusionThe results of this study show that ESCID-DC is a valid and reliable tool to assess pain in patients with acquired brain injury of different aetiology, unable to self-report and with an artificial airway.

Ethical considerationsThe study was approved by the ethics committee of the reference hospital (CEIm 20/483) and by the ethics committees or feasibility commissions of the participating centers. This research was carried out in accordance with Spanish and European Union legislation on data management and confidentiality. Written consent was obtained from the relatives/representatives of all patients included.

FundingThis work was supported by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) [Grant Number PI20/00431], Spanish title “Estudio de validez y fiabilidad de la Escala ESCID adaptada para medir el dolor en pacientes críticos con Daño Cerebral Adquirido, no comunicativos y con vía aérea artificial:ESCID-DC” and co-financed by the European Union.

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Our thanks to the coordinators and collaborating researchers of the 17 participating hospitals. To Dr. Caroline Schnakers, Dr. Gerald Chanques and Dr. Juan Roldan Merino, for their generous help in this project. Also, to the patients and their families. In particular, this study is dedicated to C.S.P., the first participant of the ESCID-DC project. Many thanks to her parents, who so generously agreed to participate.

Coordinators at the University Hospital 12 de Octubre, Madrid, Spain: Candelas López López; María Jesús Frade Mera.

Authors: Antonio Arranz Esteban; María Ara Murillo Pérez; Alejandra Alcantarilla Martín; Marta Antón Mancera; Mónica García Iglesias; Armando Sánchez Álvarez; Ana Cristina Sánchez Pacheco; Julia Ferraz Añaños; María Poyo Tirado; María Teresa Pulido Martos; Isabel Martínez Yegles; Catalina Baeza Peñuela; Blanca Bretones Chorro; María Gómez Rodríguez; Mirian Morales Cifuentes; Laura Martín Velázquez; Miguel Ángel Piña Tizón; María Luz Montero González; Luis Fernando Carrasco Rodríguez Rey.

Coordinator at the University Hospital La Paz, Madrid, Spain: Francisco Paredes Garza.

Authors: Débora Muñoz Muñoz; Andrea López Pérez; Erica Moreno Lozano; Sandra Ricote López; Carolina Hernanz García del Bello; Míriam Conde Holgado; Cristina Raya Garcia.

Coordinator at the University Hospital Doctor Josep Trueta, Girona, Spain: Aaron Castanera Duro.

Authors: Andrea Garcia Lamigueiro; Javier Rodriguez Moreno; Maria Jesus Cañete Carmona; Jordina Teixidó Lluriá.

Coordinator at the University Hospital Puerta de Hierro Majadahonda, Majadahonda, Madrid, Spain: Mónica Bragado León.

Authors: Gema María Martín Nuevo; María Elena de Juana Navío; María Vanesa de Dompablo Taboada; Teresa González Priego; Eva María Fernández-Pinilla Sánchez; Juan José García Muñoz; Manuel Camos Ejarque.

Coordinator at the University Hospital Central de Asturias, Oviedo, Spain: Emilia Romero de San Pío.

Authors: David Zuazua Rico; Julieta Alonso Soto.

Coordinator at the University Hospital of Navarra, Pamplona, Spain: Isabel Gil Saaf.

Authors: Amparo Martínez Oroz; Arantxa Roldán Reinaldo; Nely Oteiza Orradre; Esther Aguirre Pueyo; Nuria Andión Espinal.

Coordinator at the Hospital Álvaro Cunqueiro, Vigo, Pontevedra, Spain: David Alonso Crespo.

Authors: Sonia Lorenzo Vidal; Sara Arosa Rivas; María de los Ángeles González Sabajanes; Nair Rocha Pérez.

Coordinator at the University Hospital Miguel Servet, Zaragoza, Spain: Carolina Rojas Ballines.

Authors: Ana Millan López; Rubén Martínez Calvo; Laura Zueco Láinez; Alberto Moya Calvo; Elisa Guerrero Trenado: Laura Andres Gines; Horacio Enrique Jiménez Adail.

Coordinator at the University Hospital Ramon y Cajal, Madrid, Spain: Ana Castillo Ayala.

Authors: Cristina Pascual Pascual; Patricia López Martín; Diana Llorens Bra; Cristina Serrano González; Laura Zorrero Rabadán; Aránzazu Martínez Gallego; Sergio Pozo López; Clara Suay Ojalvo; Cristina Prieto González.

Coordinator at the University Hospital of Bellvitge, Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain: Gemma Via Clavero.

Authors: Verónica Giménez Villa; Meritxell Canal Reig; Daniel Rodríguez González.

Coordinator at the University Hospital of la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona, Spain: David Córdoba Sánchez.

Authors: Abel Miranda Reyes; María del Mar Vega Castosa; Roser Torrents Ros; Laura Renedo Miró; Sílvia Rodríguez Fernández.

Coordinator at the University Hospital Virgen de las Nieves, Granada, Spain: Luisa María Quesada Iáñez.

Authors: Gladys Dianet Atauconcha Dorregaray; Sara Elena Martín Sanchez; Berta García López; Margarita López Castro; Lucía Mercedes Andujar Fernández; Antonia Navarro García.

Coordinator at the University Hospital Son Espases, Palma de Mallorca, Spain: Mònica Maqueda Palau.

Authors: Barbara Catalina Ribas Nicloau; María Verónica Rodríguez.

Coordinator at the General University Hospital of Ciudad Real, Ciudad Real, Spain: Juan Carlos Muñoz Camargo.

Authors: Inmaculada Vázquez Rodríguez-Barbero.

Coordinator at the University Hospital Gregorio Marañón, Madrid, Spain: Raquel López Sánchez.

Authors: María Rojas García; Irene Martínez Pantoja.

Coordinator at the University Hospital of Getafe, Getafe, Madrid, Spain: Raquel Jareño Collado.

Authors: Mar Sánchez Sánchez; Raquel Sánchez Izquierdo; Virginia López López; Eva Sánchez Muñoz; Henar Bermejo García.

Coordinator at the University Hospital Parc Taulí, Sabadell, Barcelona, Spain: Antonia Villarrasa Millán.

Authors: Lola Perez Sanchez; Maria Esther Carrillo Santín; Miriam Secanella Martínez; Francisco José Rodríguez Ferreiro.