To determine the perception of intensive care unit nursing staff on mobbing.

MethodQualitative approach study, Grounded Theory was used, twelve intensive care unit nurses of two public hospitals in our country during December 2017.

ResultsFemale sex predominated with an average age of 41.33 years old, mostly married, on night shift and trained a nursing technicians; four categories emerged: general knowledge about mobbing, the origin of mobbing and its main actors, experiences of mobbing as a victim and as a spectator and the implications of mobbing in working life.

DiscussionIssues of workplace harassment are sensitive for most health workers, since they deal with private situations and lack of support from superiors when they have been victims of harassment. The evidence shows that one of the reasons why mobbing can be perceived in different ways is because little is known about the real concept, it can be associated with multiple forms of violence and there is heterogeneity in the use of the term.

ConclusionThe majority of intensive care unit nursing staff have been victims and witnesses of mobbing behaviour, with negative repercussions on their job satisfaction and performance; It is also the cause of constant staff turnover.

Conocer la percepción del personal de enfermería que se desempeña en la unidad de cuidados intensivos sobre el mobbing.

MétodoEstudio con aproximación cualitativa en el que se empleó la Teoría Fundamentada, se entrevistó a doce profesionales de enfermería que laboran en la unidad de cuidados intensivos de dos hospitales públicos de nuestro país, durante el mes de diciembre de 2017.

ResultadosPredominó el sexo femenino con una edad media de 41,33 años, en su mayoría casados, de turno nocturno y con estudios de técnico en enfermería; emergieron cuatro categorías: conocimiento general sobre el mobbing, el origen del mobbing y sus principales actores, experiencias de mobbing como víctima y espectador e implicaciones del mobbing en la vida laboral.

DiscusiónLos temas sobre acoso laboral resultan ser sensibles para la mayoría de los trabajadores de la salud ya que se abordan situaciones privadas y falta apoyo por parte de los superiores cuando se ha sido víctima de esto; la evidencia muestra que una de las razones por las que el mobbing puede ser percibido de distintas formas es porque se conoce poco sobre el concepto real de la palabra, se puede asociar con múltiples formas de violencia y existe heterogeneidad en el uso del término.

ConclusiónLa mayoría del personal de enfermería de la unidad de cuidados intensivos ha sido víctima y testigo de las conductas de mobbing, con repercusión negativa en su satisfacción laboral y desempeño dentro del trabajo; asimismo es causa de rotación constante de personal.

The majority of nursing staff in Intensive Care Units relate mobbing to victimisation at the workplace by managers or supervisors and which effects both the working and personal life of the victim.

What does this paper contribute?This research provides a description on the perception of mobbing by Intensive Care Unit nursing staff so that it may be identified and prevented, resulting in mental health care for this staff.

Study implicationsThe study impacts the mental health care of the nursing staff in the Intensive Care Unit with its repercussions in patient care. Regarding management, it is a part of the background to improving organisational culture, leadership and also satisfaction at work.

Workplace bullying is a combination of verbal or psychological actions carried out systematically and persistently to intimidate, stonewall or emotionally drain the victims. It generally occurs between workplace colleagues or those higher up in the hierarchy.1 Workplace bullying is also called mobbing, a term which was introduced during the 1980′s by Dr. Heinz Layman to refer to a series of behaviours which generated psychological violence and a lack in ethics in communication inside the workplace or in different contexts linked to it.2

Mobbing causes stress and other psychological problems such as depression and anxiety, which are linked to a reduction in productivity at work and a deterioration in interpersonal relationships. Its main causes are low support for workers, lack of leadership, policies within the workplace which do not consider the mental health of the workers and the lack of autonomy in decision making.3 People who perform at jobs involving public administration and the health sector are identified as having a propensity to present with mobbing4 behaviour patterns.

The nursing staff of the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) is one of the professional sectors most affected by mobbing due to the lack of communication and problems among colleagues and to the verbal abuse suffered at the workplace.5–7 Among the risk factors relating to mobbing in the nursing staff are being under 30 years of age, male, single, with a lower level of education and little working experience. Low satisfaction with work and performing in the ICU is also associated with this behaviour.8

When nurse managers are identified as the perpetrators of violence or mobbing, the atmosphere is perceived as unhealthy, and this situation hinders professional development and in a constant staff turnover.9 A leadership style that takes into consideration participation from nursing staff helps to reduce levels of tension among colleagues. However, it is important to mention that mobbing presents due to mulifactorial causes, and participative leadership does not resolve this problem.10

We should mention that nursing staff perceived that some behaviours, such as being innovative, hard-working, not being intimidated or overruled by colleagues, cause envy in the workplace and promote mobbing.11 This situation may be due to the fact that the majority of students who choose a nursing career are from a low social and economic background and the average previous entry level is also lower than the mean, with nursing not therefore being their first option.12 These are contributing factors to professional development frustration.

Despite the fact that the majority of nursing staff say they have been a victim of workplace bullying or verbal abuse, these cases are not reported,13 and it is therefore likely that mobbing will continue to rise, particularly in high risk areas such as the ICU. The aim of this study was therefore to determine the perception of ICU nursing staff regarding mobbing.

MethodA descriptive, qualitative study conducted in December 2017. The systematic design of grounded theory was used. This design, unlike others, leads to subdivision by stages in open, axial and selective coding to generate categories and subcategories which together are able to describe the reality observed.14 From the phenomenon of interest, each individual perceives reality based on their circumstances there are therefore different meanings which the researcher has to combine to develop an understanding as a whole.15

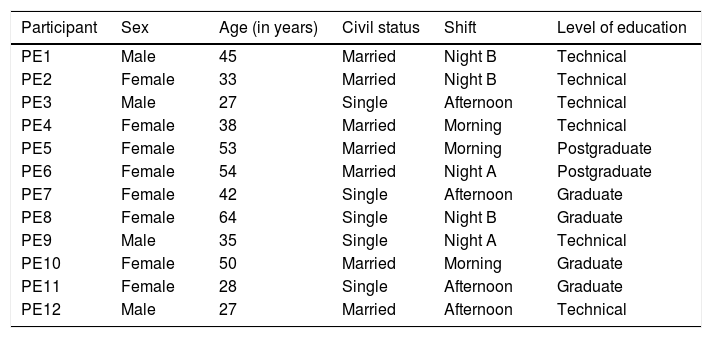

Purposive sampling was made using a key informant who collaborated as a contact with all of the other staff. With this type of sampling the idea is to seek in-depth knowledge on the study phenomenon.15 Out of a total of 35 nursing professionals of the ICU who carried out operative functions in 2 public hospitals, we sought participants who met with the following criteria: 1) Over 5 years of experience in the ICU; 2) professional staff including: nursing technicians, graduates and post-graduates and 3) who carry out activities that involve direct patient care (Table 1). The final sample consisted of 12 participants up to category saturation, since no different information from that already collected was obtained and this became repetitive after performing open coding.14,15

Characteristics of the Intensive Care Unit nursing professionals.

| Participant | Sex | Age (in years) | Civil status | Shift | Level of education |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE1 | Male | 45 | Married | Night B | Technical |

| PE2 | Female | 33 | Married | Night B | Technical |

| PE3 | Male | 27 | Single | Afternoon | Technical |

| PE4 | Female | 38 | Married | Morning | Technical |

| PE5 | Female | 53 | Married | Morning | Postgraduate |

| PE6 | Female | 54 | Married | Night A | Postgraduate |

| PE7 | Female | 42 | Single | Afternoon | Graduate |

| PE8 | Female | 64 | Single | Night B | Graduate |

| PE9 | Male | 35 | Single | Night A | Technical |

| PE10 | Female | 50 | Married | Morning | Graduate |

| PE11 | Female | 28 | Single | Afternoon | Graduate |

| PE12 | Male | 27 | Married | Afternoon | Technical |

Regarding organisation, both units have professional nursing staff that carry out integral patient care activities. The operational personnel of both units are composed of nursing technicians, graduates and post-graduates; each individual carries out the said activities regardless of their academic qualification and continuous training is therefore required. However, there is a difference in salary depending on academic level. There is one person in charge per shift and a head of service who works on the morning shift. The working day is fixed.

The main researcher was a nurse with doctorate studies in administration and 10 years of experience in direct patient care in the ICU. They remained for 6 weeks in the clinical field of each hospital institution prior to the study during the months of October and November 2017 so as to establish contact and gain the trust of the participants. Staff were personally invited to join the study. After talking about the objectives and dynamics of the study, 7 people decided not to participate, in particular the male nursing staff who said they had too heavy a workload and lacked information on mobbing. A participative observation technique was used to create rapport.16

In keeping with the literature regarding mobbing, an interview guide was developed composed of the following questions: 1) what is mobbing?, 2) have you been a victim of mobbing and in what way?, 3) What are the causes of mobbing and for you who are the people responsible?, 4) Have you noticed any other form mobbing among your colleagues?, and 5) What implications do you consider mobbing has in your job? It is important to mention that the interview was based on a guideline but the interviewer had the freedom to ask additional questions to probe information.14

A recorder and a field diary was used during the interviews—with prior consent from respondents—, where the researcher recorded the most relevant items regarding the non verbal language of the respondents after each interview (the refusal to continue with the interview, and also reactions of discomfort during the questioning). Each interview was transcribed word for word to meet with confirmability criterion and the scientific rigour of the qualitative research.14

Interviews were conducted personally and privately in the head of service’s office, during the working day of each participant and when workload was lower, with no interference in activities. Each interview lasted between 20 and 35 min. On termination, the interviews were fully transcribed by word processor. The interviews were read line by line to identify patterns that stood out from the text. Afterwards, work files were used and a conceptual map for origination and key word linking was created. Open, axial and selective coding were performed for data analysis.15,16

Scientific rigour was established by adhering to the principles of dependability, credibility, transferability and confirmability14; the interviews were presented to the participants with the aim of obtaining their approval. After this, the results were presented to 3 professors with experience in qualitative research and one of them with experience in the ICU as operational personnel. The final results were again presented to the participants for validation.

The study adhered to that stipulated in the General health Law regulation governing the field of research into health.17 It was also approved by the authorities of the accounting and administration faculty of the Autonomous University of Chihuahua and the 2 participating hospitals. The staff who agreed to participate was provided with an informed consent form informing them of their right to withdraw from the study at any time.

ResultsTwelve interviews were conducted with the nursing staff. There was a predominance of 8 female participants, with a mean age of 41.33 years. They mostly worked night shifts and were married. Regarding educational levels, half of them were nurse technicians (Table 1).

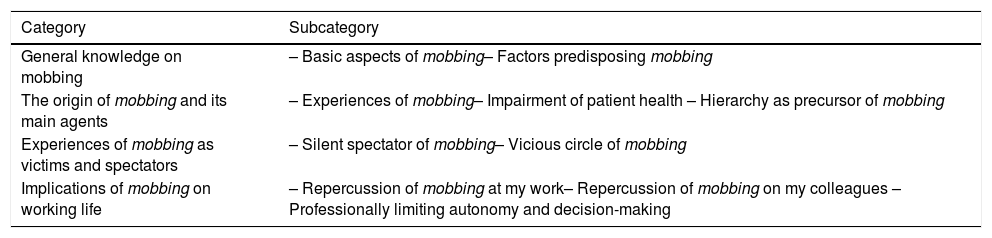

Four categories and 10 subcategories emerged regarding the perception and knowledge on mobbing in the nursing staff: 1) general knowledge on mobbing; 2) the origin of the mobbing and its main agents; 3) experiences of mobbing as victim and spectator, and 4) implications of mobbing at the workplace (Table 2).

Categories and subcategories from perceptions of mobbing among the Intensive Care Unit nursing staff.

| Category | Subcategory |

|---|---|

| General knowledge on mobbing | – Basic aspects of mobbing– Factors predisposing mobbing |

| The origin of mobbing and its main agents | – Experiences of mobbing– Impairment of patient health – Hierarchy as precursor of mobbing |

| Experiences of mobbing as victims and spectators | – Silent spectator of mobbing– Vicious circle of mobbing |

| Implications of mobbing on working life | – Repercussion of mobbing at my work– Repercussion of mobbing on my colleagues – Professionally limiting autonomy and decision-making |

It was important to determine what concept the ICU nursing staff has about mobbing in order to identify and report it when it presents. Most of them have some notion about mobbing and relate it to violence at the workplace; they also perceive it as mistreatment or harassment, on some occasions perpetrated by superiors in the workplace: ”It’s the abuse the workers suffer from by their superiors” (PE03); ”It’s the harassment people suffer from by their bosses” (PE04); “We could call it mistreatment in the workplace or rather almost always related to the working environment “(PE12).

Some of mobbing behaviour in the ICU is mainly based on what nursing staff perceive as strict supervision of care offered to the patient, unfair work load and distribution and the omission of staff employment rights. Some participants responded: ”For example, with regards to me, it’s just that they were overly strict about revising how I worked, they came and watched me all the time, if I was providing aspiration to the patients” (PE04); “When they give all the work to one single person or when they don’t let us get time off or ask for time off that is owed to us (PE05); “Mistreatment when the shift changes, because then [the head of service] begins to question the patients, asking them if we have washed them and that, even the supervisors do not provide us with people, they leave us on our own or they refuse to give us the leave we are owed” (PE06).

The origin of mobbing and its main agentsThe nursing staff who work in the ICU service are exposed to many different moods and behaviours within the service, interacting daily with people who are critically ill and others who are vulnerable due to the condition of their family members, with the add-on of continuous stress due to work overload and colleagues who are at the same or a higher hierarchical level than them who under-appreciate them: ”It is very stressful not being able to do anything for patients who are seriously ill, and for the suffering of their family members “ (PE11); ”It is very difficult to co-exist with colleagues who become insensitive or extremely sentimental about the patients’ conditions and the demands of their families” (PE04); ”I get very stressed out by work overload because I think I won’t finish things and then I see other colleagues who are not doing anything …” (PE06); ”It can occur due to professional envy, professional jealousy, that you don’t get on with someone and even to the simple fact of making people feel bad” (PE10). ”[…] the boss’s fear that they will get rid of his or her position and they make you feel smaller” (PE03).

In the ICU service one of the main agents of mobbing is the manager or supervisor because they wish to demonstrate their power over the operational personnel. Alps, on occasions, people behave negatively towards colleagues who wish to excel, detracting from the value of human capital. In this respect some people mentioned: ”The manager or superior or person who has greater power is the one who harasses us generally “(PE 3); ”Well I think it is mainly people in high positions who abuse their power, who play out the role of boss if not of leader” (PE12); ”It has mainly been my bosses, when I came into the school they did not support me, they did not want to change my shift to help me get on” (PE06); «”The bosses, as soon as they are assigning you your duties they ask you if you would like to work in a particular service and if you say you wouldn’t they send you there and say, see if you can come to terms with it” (PE09).

Mobbing behaviour patterns and workplace abuse are common between colleagues at the same hierarchical level. These maybe become physical aggression. Some of the causes stem from different intellectual capacities and peer-to-peer clinical skills observed and as the consequence of continuous staff turnover. To this participants responded as follows: ”In my case I have seen this to be more between work colleagues” (PE06); ”Some of my work colleagues hit me” (PE04); ”It is mostly work colleagues who do not like someone else to know more than they do” (PE12); ”My actual colleagues, it was so bad I had to ask for a change of service” (PE10).

Experiences of mobbing as victim and spectatorMobbing is definitely present in the ICU context and is persistent. Most nursing staff have had to experience it, with different intensity. The staff were asked if they had been witnesses to bullying behaviour towards their colleagues. In this respect the respondents mentioned: ”Yes, on many occasions I have witnessed harassment” (PE02); ”Yes, with many colleagues” (PE05); ”Yes, it is highly common between the other colleagues and with some people it is more severe, very serious” (PE09). Being a witness to mobbing does not exonerate the person from being a victim within the same act. The nursing staff were asked if they had suffered from mobbing at any time and responded: “[…] On many occasions, both physically and verbally” (PE08); “Yes, boycotting my work, telling me I did not work enough and changing me to a different department where I could not develop” (PE03); ”Yes, since when I started working and all these years later this is still happening” (PE10).

Although it is true that mobbing is always present among the ICU staff, the spectator is silent and passive, since he or she witness the mobbing but do not get involved until it has finished and generally, it is people with greater experience behaving in this way to those with less: ”Yes, and as I experienced it in some way I have tried not to defend but to make the other person understand when they are behaving badly” (PE11); ”Yes, often I have witnessed verbal threats but what does one do…. people with more experience regularly belittle more “… (PE01); ”I have often see how they shout at colleagues for different reasons but the truth is I am afraid to interfere with the bosses because they would do the same to me after “(PE04).

Implications of mobbing on working lifeThe worker’s performance is one of the spheres which is most affected when they are a victim of mobbing, because the pressure exerted on the person leads to continuous stress, lack of motivation and they become increasingly conformist: ”Workplace bullying ruins inspiration and daily strength” (PE05); «”You can’t concentrate properly, you tend to be a bit more distracted and with greater pressure outside work” (PE06);”I feel like I am always stressed and in a bad mood” (PE09);” You lose all motivation to improve and it’s as if you become more conformist, in all spheres” (PE10). Furthermore, the perception of ICU nursing staff on colleagues is as follows: ”It’s simply that your colleagues are not happy nor do they let you be happy” (PE6).

Another implication of mobbing is that performance at work and productivity are affected. The ICU nursing staff does not carry out care procedures independently, since there is the continuous stress provoked by the reduction of autonomy and decision-making. Their work is therefore singularly based on instructions from their superiors, limiting their personal growth and reducing the pleasure and passion in their work. In this respect, some participants mentioned that mobbing: ”Affects you mentally, you no longer take things seriously, you no longer perform with quality or passion, you are only thinking that they are going to harass you again” (PE01); ”I am not acting professionally because they guide you to do the work as they say and not as it should be done and whatever you do, they will say you did it wrong” (PE03); ”Out of fear you no longer do things happily, and you are always afraid, so you do not even perform as you used to, so you are never going to be able to look after the patient well” (PE04); ”You no longer come to work happily for the working day” (PE07).

DiscussionIn this research study female participants predominated, with a mean age of 41.33 years. These results were similar to those reported in another study, where it was notable that the male sex was one of the main factors associated with mobbing.18 when the invitation to the study was made, most male nursing staff rejected participation giving their reasons as lack of knowledge and overburden of work. It should be mentioned that the issues of workplace bullying is sensitive for most health workers, since private situations are involved and there is a lack of support from superiors when one has been a victim of harassment.19

The inclusion of males into the nursing profession is not new. However, their recognition within this discipline has been low due to the fact that nursing is principally viewed as a female profession, which has combined to form a cultural stereotype of the female chauvinist within it.20 It is probable that this reversal of roles is one of the causes why male nurses find it difficult to report that they have been victims of mobbing and, therefore, why they are reluctant to participate in studies on this issue.

The results of this study show that the ICU nursing staff perceive of mobbing as workplace bullying and abuse at work, mainly carried out by their hierarchical superiors. A study conducted in Turkey reports that the majority of nursing staff perceive of managers and hierarchical superiors as the main perpetrators but that on some occasions these behaviours are not reported.21 One of the reasons why mobbing may be perceived in different ways is because little is known about the real concept of the word. It may be associated with many different forms of violence and the term is used heterogeneously.8

A reduction in organisational culture within the workplace is found to be related to the increase in mobbing among nursing staff, and the style of leadership exercised by senior nursing staff22 therefore needs to be determined. In keeping with the findings from this research, the majority of operational nursing staff in the ICU perceive of managers and supervisors as the main perpetrators of mobbing behaviour towards them because working conditions are not respected and supervision is overly strict.

Nursing staff in managerial positions also have difficulties due to lack of support from the organization, problems in communication and aggression from patients and family members.23 Furthermore, regarding nursing staff in supervisory positions, few have postgraduate studies in administration and few fulfil functions of management and training. The recruitment of these professionals is therefore not based on skills but on appointments. They themselves also perceive that there is very little recognition by management of what they do.24

In this research, nursing staff responded that they had been victims of mobbing by their colleagues at the same hierarchical level as themselves. When good relationships ensue between colleagues satisfaction with work increase and therefore any abuse between nursing staff diminishes.25

One of the main findings from this research was that nursing staff have been passive witnesses of mobbing towards their colleagues but for several reasons they did not interfere when this harassment took place. When nursing staff are witnesses to mobbing, higher stress levels than those of the actual victims present and there is a loss of interest in the job and the profession, leading to debasement of the discipline.5

It is important to state that one of the main consequences of mobbing among ICU nursing staff is a reduction in productivity and demotivation. Negative behaviour, humiliation and abuse lead to low self-esteem in the workplace. They are also associated with adverse events and a reduction in the quality of patient care and safety.25,26

It is essential to care about the mental health of the ICU nursing staff, reduce mobbing behaviour patterns and improve human relationships. One study conducted with ICU nursing staff in Korea reported moderate job satisfaction, and a high prevalence of mobbing, making this the most highly experienced type of abuse in this professional sector. Optimization of the atmosphere at work reduces this type of behaviour.27 It should be mentioned that despite high levels of workplace harassment among ICU nursing staff, the level of prevention is very low.7 These factors may be associated with the so-called burnout or exhaustion syndrome, which is high among ICU nursing staff and which has a negative impact on the health of the worker and productivity at work.28

One of the limitations of this study was the difficulty of getting male staff to participate in the interviews. It should also be mentioned that work overload and stress made in-depth interviews difficult to conduct within the workplace setting.

ConclusionsICU nursing staff perceive of mobbing as workplace bullying, mostly carried out by colleagues of superior hierarchy, and mainly consisting of unfair distribution of work and omission of employment rights. Little is known about what this behaviour entails.

Stress, a feeling of disrespect and lack of human capital appreciation are forms of mobbing perceived by the ICU nursing staff. Some of these behaviour patterns lead to physical abuse and constant rotation of staff.

Most ICU nursing staff have been the victims and witnesses of mobbing, with negative repercussions in their satisfaction at work and performance at work, causing constant staff turnover.

FinancingNone.

Conflict of interestsNone.

Please cite this article as: Ruíz-González KJ, Pacheco-Pérez LA, García-Bencomo MI, Gutiérrez Diez MC, Guevara-Valtier MC. Percepción del mobbing entre el personal de enfermería de la Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos. Enferm Intensiva. 2020;31:113–119.