In this study researchers are trying to analyse the personality factors related to social skills in nurses who work in: intensive care units, ICU, and hospitalisation units. Both groups are from the Madrid Health Service (SERMAS).

MethodThe present investigation has been developed as a descriptive transversal study, where personality factors in ICU nurses (n=29) and those from hospitalisation units (n=40) were compared. The 16PF-5 questionnaire was employed to measure the personality factors associated with communication skills.

ResultsThe comparison of the personality factors associated to social skills, communication, in both groups, show us that nurses from ICU obtain in social receptivity: 5.6 (A+), 5.2 (C−), 6.2 (O+), 5.1 (H−), 5.3 (Q1−), and emotional control: 6.1 (B+), 5.9 (N+). Meanwhile the data does not adjust to the expected to emotional and social expressiveness, emotional receptivity and social control, there are not evidence.

ConclusionsThe personality factors associated to communication skills in ICU nurses are below those of hospitalisation unit nurses. The present results suggest the necessity to develop training actions, focusing on nurses from intensive care units to improve their communication social skills.

Como objetivo de este estudio nos planteamos analizar los rasgos de personalidad asociados a las habilidades sociales de las enfermeras que trabajan en las unidades de cuidados intensivos (UCI) y las enfermeras que trabajan en unidades asistenciales de hospitalización de adultos, ambos grupos pertenecientes al Servicio Madrileño de Salud (SERMAS).

MétodoSe realizó un estudio descriptivo transversal con 69 enfermeras del SERMAS, de las cuales 29 eran enfermeras asistenciales de UCI y 40 enfermeras de Hospitalización, utilizando el cuestionario 16PF-5, para medir los factores de personalidad ligados a las habilidades sociales.

ResultadosEn el grupo de enfermeras de UCI aparecieron factores ligados a habilidades sociales en receptividad social: 5,6 (A+), 5,2 (C−), 6,2 (O+), 5,1 (H−), 5,3 (Q1−) y en control emocional: 6,1 (B+), 5,9 (N+). No se encontraron factores asociados a expresividad emocional, expresividad social, receptividad emocional y control social.

ConclusionesLos valores encontrados para los rasgos y factores de personalidad asociados a las habilidades sociales de comunicación en enfermeras de UCI son inferiores a los encontrados en las enfermeras de Hospitalización. Consideramos clave realizar actividades de intervención y formación específica para desarrollar las habilidades sociales de comunicación en las enfermeras de UCI.

Social skills associated with communicating with patients and their family are particularly relevant in the health-care we provide, both in intensive care units (ICU) and in other care units where nurses work. There are various articles that analyse the importance of communication between nurses, relatives and patients on the ICU, but we have not found any recent studies that assess such skills as proven tools for ICU nurses.

The contribution of this research is to validate a questionnaire to be used to gauge social skills associated with communication, 16PF-5, and to make it possible to check that ICU nurses have such skills compared with admissions nurses and the general public.

Only if we check this and assess it, will we be able to know which social skills the professional body has and which they do not, and we will be able to put improvement measures in place, should it be necessary.

Implications of the studyThe implications of the study involve bringing to light the social skills associated with communication that ICU nurses have in a sample from the Madrid Health Service. The aim is to raise the profile of communication with relatives and ICU patients, to be used as an example for monitoring that personality factors associated with social skills in other ICUs. This will act as a tool for improvement for increasing the quality that the relatives and patients experience.

In their line of work, nurses working in intensive care units (ICUs) have to deal with very difficult situations: the type of patients they care for are in a life-or-death situation, they often have to deal with death; they have higher mortality rates that the rest of the hospital. They have to go through the pain and suffering of the relatives and loved-ones of the patients who have been admitted to the ICU. This opens up the possibility that nursing professional could have a profile and behavioural traits different to those in other care departments in the hospital, such as Admissions.

Nursing is a career that is both scientific and humanistic, and it is based on both biological and behavioural science. At the ICU, it is of the utmost important to keep the close relatives informed and cared for, due to the specific characteristic of the patient, (sedated, intubated, in a coma, etc.), which makes it very difficult to communicate with the patient directly and makes for very distinct working conditions on these types of units.1

Intensive care nurses are carrying out checks on the patient 24/7. Families value the nurses’ skills, especially efficient communication, which is deemed to be one of the most important skills of health-care staff working at the ICU.2

In nursing, the care relationship is based on attitude, skills and relationships that develop over the course of the care provided to patients and their relatives. An important aspect of this relationship is active listening.3

From an ICU management and organisational point of view, one of the key aspects is information and communication with the families. It is important to treat the families as part of the patients’ environment, since the complexity and severity of the situation in ICUs are much greater and generate tense situations and high levels of stress in the families of this type of patients.4,5

Nurses must provide information related to care and the procedures being carried out on the patient; this is an ethical, professional and legal requirement. Communication skills are basic when it comes to working in any health-care job, since they allow for the application of conceptual or technical knowledge, through the relationship with the patient or user.6

According to Henneman et al.,7 the relatives of critically ill patients state that what they need most is information. They want to get information both from the doctor and the nurse in question. They want information from the nurse about the patient's care and daily development, regarding the features of the unit and the visiting hours.8

In some studies, it has been shown that ICUs need quality standards regarding the care relationship with the family. Nurses are not sure about what type of professional relationship they should have with the family.9

If we analyse the communication process in the context of the ICU, factors can appear that may interfere both with the health-care staff and the patients’ families.9,10 These are the following factors:

- •

Regarding the person giving the information, (doctor or nurse), it is possible that they do not have experience in giving information, they do not know the family and their problems, or they do not know what information they already have or have requested before.

- •

Regarding the person receiving the information, (the relative), it is possible that they get information from various doctors and nurses, stress may prevent them from understanding the message properly, and they may need to keep asking for the same information.

- •

Regarding the characteristics of the message, it should be pointed out that they often do not use the right language, using technical jargon and explaining things that are difficult to understand for non-professionals.

- •

Lastly, the professional may have distant or indifferent attitudes as an attempt to protect themselves and avoid sharing in the patient's suffering, which can make communication difficult.

Regarding social skills associated with communication with other people, it should be pointed out that Riggio11 suggested that these can be divided into three types of communications: (a) expressiveness or providing information; (b) receptiveness or receiving information; and (c) controlling information. Each skill is measured on two levels, one is non-verbal (called emotional) and the other is verbal (called social), which breaks these three types down into 6 dimension: (a) emotional expressivity (EE); (b) social expressivity (SE); (c) emotional receptivity (ER); (d) social receptivity (SR); (e) emotional control (EC); and (f) social control (SC).11

The expressivity scales look at interacting with other people and initiating communication; these features are also related to extraversion. Receptivity involves the ability to take in and interpret information, but the two scales, emotional and social, differ on how they relate to personality. Control is the external regulation and adjustment of information. In summary, these 6 scales together allow us to get a summary value of communication social skills.11,12

Bearing in mind the important of workplace communication for nursing professionals, the aim of this study is to analyse personality traits associated with social skills, focussing on communication with other people, patients and relatives, among nurses working in the adult ICU in the Madrid Health Service (SERMAS), and comparing them with the nurses that working in general admissions health-care units for adults, as well as with the average for the Spanish population.

MethodA cross-sectional descriptive study was carried out between August and November 2015.

The target population group in this study was nursing professionals working in health-care in the public hospitals run by SERMAS in Spain; more specifically in Getafe University Hospital and the Fuenlabrada University Hospital. The criteria for including participants in the study were the following: (a) holding a diploma or degree in nursing; (b) being in work at the time of the study; and (c) working in an ICU or Admissions unit. It should be pointed out that the ICUs selected were polyvalent and for adults; the admissions units were for acute adult patients for medical or surgical services, except gynaecology and midwifery.

Regarding the estimated sample size, the size of the population group for this research was (n for ICU=88, n for Admissions=212), the confidence interval was 95% (1.96 value). Similarly, it was deemed that we were faced with a possibly disadvantageous situation regarding the variability in the population group. Therefore, in this study, it has been deemed that p=q=50%. The maximum percentage error margin in this study was 15%. The researchers are aware that this is a high error margin, but the rate of participation from the groups in the study was low. In fact, in this study, it was found that out of all the ICU nurses working at both hospitals, only 32.9% took part, while out the total admissions nurses, it was only 18.9% of the total.

It should be pointed out that the research handled in this study has been assessed and approved by the Medical Research Ethics Committee at the Getafe University Hospital in Madrid, Spain. The nurses voluntarily accepted to take part in the study by signing a consent form.

The variables included were: (a) socio-demographical, age and sex; (b) work-related, unit and centre where they worked, and (c) personality traits included in 16PF-5.

The study and data collection were carried out in two distinct stages. The first stage was carried out in contact with the nursing professionals, through the nursing management team at the hospital where they worked, once the professionals were aware of the study and its aims. Those who voluntarily wished to take part went into the second part of the study once they had signed the informed consent form in which they agreed to take part. In the second stage, the participants then filled out the 16PF-5 questionnaire,13 using primary and global factors to gauge this, which allowed us to list and analyse their social skills, focussing on interpersonal communication and those associated with 6 dimensions according to Riggio11 that make up social skills for communication.

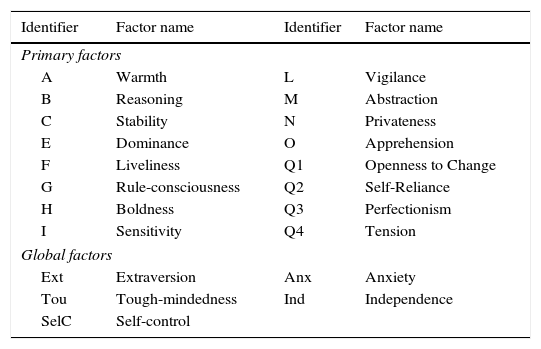

The questionnaire used for this study to identify the factors associated with social skills for communication was 16PF-5, which is a factorial personality questionnaire. It involves a structured test, often used by researchers and psychologists around the world as a tool for measuring and understanding personality. This questionnaire measures 16 basic factors and 5 global factors (Table 1), and it took roughly 45min for the volunteers to fill it out.

Basic and global factors assessed in the 16PF-5 questionnaire.

| Identifier | Factor name | Identifier | Factor name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary factors | |||

| A | Warmth | L | Vigilance |

| B | Reasoning | M | Abstraction |

| C | Stability | N | Privateness |

| E | Dominance | O | Apprehension |

| F | Liveliness | Q1 | Openness to Change |

| G | Rule-consciousness | Q2 | Self-Reliance |

| H | Boldness | Q3 | Perfectionism |

| I | Sensitivity | Q4 | Tension |

| Global factors | |||

| Ext | Extraversion | Anx | Anxiety |

| Tou | Tough-mindedness | Ind | Independence |

| SelC | Self-control | ||

This questionnaire was created by the American psychologist Cattell et al.,13 and it was adapted into Spanish by Seisdedos,14 who also duly adapted and validated it for the context in Spain.

16PF-5 allows us to determine different personality factors, which are measured using this questionnaire, with social skills for communication. This association was based on the study conducted by Riggio15 in 1989, measuring basic social communication skills and it was concluded that knowing about such skill can help the subject to develop them and put them to use in applied situations in training and personal development.

The personality factors assessed in 16PF-5 that make up the social skills for communications are the following: dominance (E+), boldness (H+), privateness (N−), rule-consciousness (G−) and tension (Q4+). Social expressivity included the following personality factor: boldness (H+), liveliness (F+), privateness (N−) and openness to change (Q1+). Emotional receptiveness was made up of: warmth (A+) and openness to change (Q1+), while social receptiveness was defined by: apprehension (O−), warmth (A+), stability (C−), boldness (H+), openness to change (Q1+) and tension (Q4−). Lastly, emotional control was defined by: apprehension (O−), privateness (N+) reasoning (B+), while social control was defined by: reasoning (B+), dominance (E+), boldness (H+), openness to change (Q1+), perfectionism (Q3+) and vigilance (L−).16

It should be borne in mind that when a factor appears as + it is expected that the score obtained by the population group studied would be higher than the average population (5.5 points) to associate this factor with social skills, and if it appears as − it is expected that the score obtained by the sample studied for this factor will be lower than the average population, so that it can also be associated with social skills. The direct scores from 16PF-5 will be put on to a normal 10 point scale called decáptios, with an average of 5.5 on the decápito for the Spanish population average and a typical deviation of 2 decápitos.

The statistical analysis conducted to compare the experimental group was carried out using Student's t test, and if the normality rests failed, the Mann–Whitney U-test was used. The statistic significance level in this study was set at p<0.05. The statistical analysis was conducted using SigmaStat 3.5 software. (Point Richmond, USA.

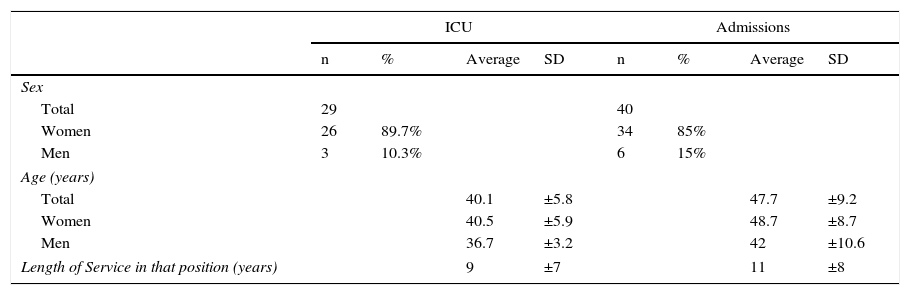

ResultsDescription of the population studied69 nursing professionals participated in the study, all of whom worked in health-care in public hospitals run by SERMAS, of which 29 worked in adult ICUs and the other 40 worked in adult medical admissions.

Analysing the characteristics of the 69 professional (Table 2) we can see that 60 of them were women, making up 89.6% of the total. The age of the participants ranged between 27 and 58 years of age; the average was (SD) 44.5 (±8.7) (45.1 [±8.6] for women compared with 40.2 [±8.9] for men).

Demographical information about the groups in the study, ICU and Admissions.

| ICU | Admissions | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | Average | SD | n | % | Average | SD | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Total | 29 | 40 | ||||||

| Women | 26 | 89.7% | 34 | 85% | ||||

| Men | 3 | 10.3% | 6 | 15% | ||||

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| Total | 40.1 | ±5.8 | 47.7 | ±9.2 | ||||

| Women | 40.5 | ±5.9 | 48.7 | ±8.7 | ||||

| Men | 36.7 | ±3.2 | 42 | ±10.6 | ||||

| Length of Service in that position (years) | 9 | ±7 | 11 | ±8 | ||||

The percentage of women is listed compared to the total participants in each group, as well as the average and standard deviation (SD) of the variables for age and length of service.

The statistic significance level in this study is p<0.05.

Regarding the two groups analysed, it can be seen that the total nursing staff that worked in the ICU (29 people), 26 were women, making up 89.7% out of the total. The average age of the participants in this group was 40.1 (±5.8), ranging between 27 and 52 years of age, 40.5 (±5.9) for women compared with 36.7 (±3.2) for men.

Regarding the two groups analysed, it can be seen that the total nursing staff that worked in Admissions (40 people), 34 were women, making up 85% out of the total. The average age of the participants in this group was 47.7 (±9.2), ranging between 27 and 58 years of age, 48.7 (±8.7) for women compared with 42 (±10.6) for men.

Similarly, when comparing the length of service in the jobs, measured in years, the nurses in the ICU and Admissions, we have an average length of service for the first group at 9 (±7) years, while the average length of service for the Admissions group was 11 (±8).

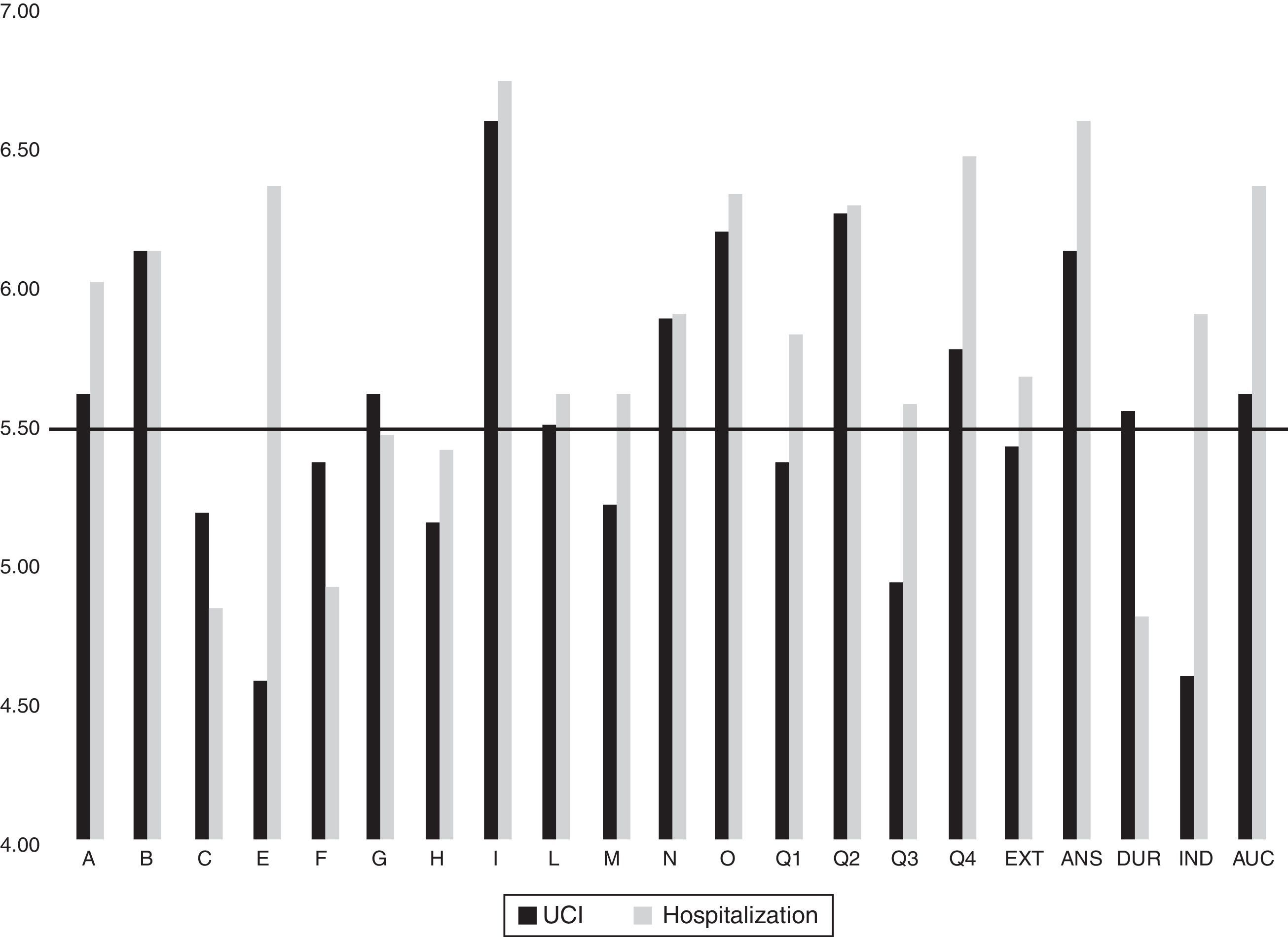

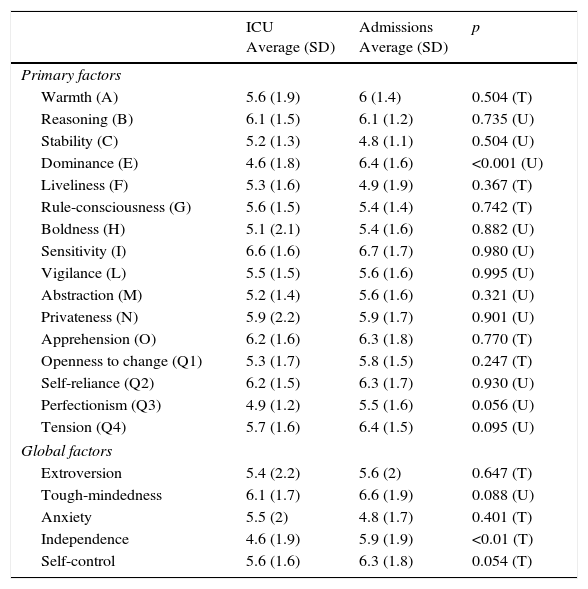

Assessment of the personality traits that define social skills for communicationThe scores achieved were compared for each of the factors obtained through the 16PF-5 questionnaire with Spanish population average for both sexes, with a value of 5.5 points (Table 3).

Average scores for the primary and global factors for the study groups (ICU and Admissions) and comparison between the groups.

| ICU Average (SD) | Admissions Average (SD) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary factors | |||

| Warmth (A) | 5.6 (1.9) | 6 (1.4) | 0.504 (T) |

| Reasoning (B) | 6.1 (1.5) | 6.1 (1.2) | 0.735 (U) |

| Stability (C) | 5.2 (1.3) | 4.8 (1.1) | 0.504 (U) |

| Dominance (E) | 4.6 (1.8) | 6.4 (1.6) | <0.001 (U) |

| Liveliness (F) | 5.3 (1.6) | 4.9 (1.9) | 0.367 (T) |

| Rule-consciousness (G) | 5.6 (1.5) | 5.4 (1.4) | 0.742 (T) |

| Boldness (H) | 5.1 (2.1) | 5.4 (1.6) | 0.882 (U) |

| Sensitivity (I) | 6.6 (1.6) | 6.7 (1.7) | 0.980 (U) |

| Vigilance (L) | 5.5 (1.5) | 5.6 (1.6) | 0.995 (U) |

| Abstraction (M) | 5.2 (1.4) | 5.6 (1.6) | 0.321 (U) |

| Privateness (N) | 5.9 (2.2) | 5.9 (1.7) | 0.901 (U) |

| Apprehension (O) | 6.2 (1.6) | 6.3 (1.8) | 0.770 (T) |

| Openness to change (Q1) | 5.3 (1.7) | 5.8 (1.5) | 0.247 (T) |

| Self-reliance (Q2) | 6.2 (1.5) | 6.3 (1.7) | 0.930 (U) |

| Perfectionism (Q3) | 4.9 (1.2) | 5.5 (1.6) | 0.056 (U) |

| Tension (Q4) | 5.7 (1.6) | 6.4 (1.5) | 0.095 (U) |

| Global factors | |||

| Extroversion | 5.4 (2.2) | 5.6 (2) | 0.647 (T) |

| Tough-mindedness | 6.1 (1.7) | 6.6 (1.9) | 0.088 (U) |

| Anxiety | 5.5 (2) | 4.8 (1.7) | 0.401 (T) |

| Independence | 4.6 (1.9) | 5.9 (1.9) | <0.01 (T) |

| Self-control | 5.6 (1.6) | 6.3 (1.8) | 0.054 (T) |

The data related to the average value and the standard deviation (SD). The statistical tests used were Student's t test (T) and the Mann–Whitney U-test (U).

The statistic significance level in this study is p<0.05.

Looking at the results obtained for the nursing staff working in the ICU group, the most relevant personality traits (differences greater than 0.5 points compared to the population average) were the following: reasoning +, dominance −, sensitivity +, apprehension +, self-reliance +, perfectionism −, tough-mindedness + and independence −.

In the group made up of nursing staff working admissions, we found the following relevant personality traits (differences greater than 0.5 points compared to the population average): warmth +, reasoning +, dominance +, liveliness −, sensitivity +, apprehension +, self-reliance +, tension +, tough-mindedness +, anxiety −, self-restraint +.

Comparing the personality factors between the two groups, ICU and Admissions, we have a statistic significance between the dominance and independence factors, in favour of the Admissions nurses (Table 4).

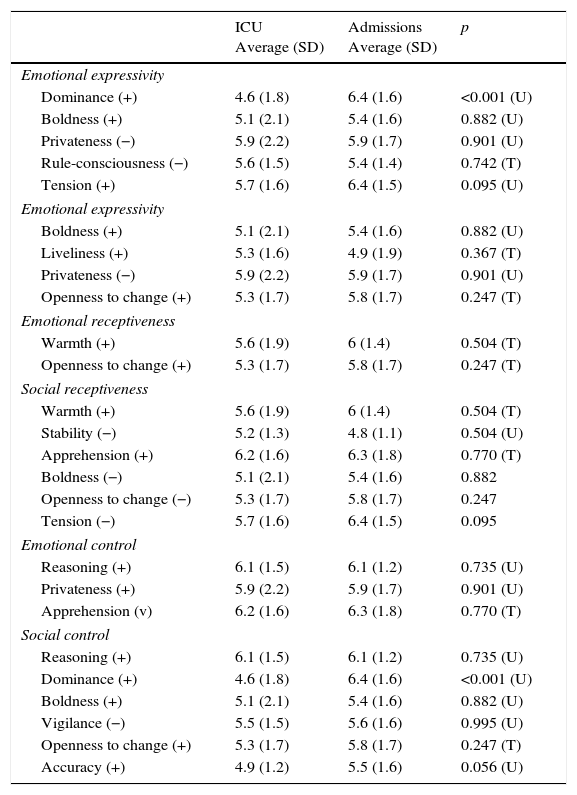

Assessment and comparison of the factors defined for the different scales that define social skills for communication in the study groups: ICU and Admissions.

| ICU Average (SD) | Admissions Average (SD) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional expressivity | |||

| Dominance (+) | 4.6 (1.8) | 6.4 (1.6) | <0.001 (U) |

| Boldness (+) | 5.1 (2.1) | 5.4 (1.6) | 0.882 (U) |

| Privateness (−) | 5.9 (2.2) | 5.9 (1.7) | 0.901 (U) |

| Rule-consciousness (−) | 5.6 (1.5) | 5.4 (1.4) | 0.742 (T) |

| Tension (+) | 5.7 (1.6) | 6.4 (1.5) | 0.095 (U) |

| Emotional expressivity | |||

| Boldness (+) | 5.1 (2.1) | 5.4 (1.6) | 0.882 (U) |

| Liveliness (+) | 5.3 (1.6) | 4.9 (1.9) | 0.367 (T) |

| Privateness (−) | 5.9 (2.2) | 5.9 (1.7) | 0.901 (U) |

| Openness to change (+) | 5.3 (1.7) | 5.8 (1.7) | 0.247 (T) |

| Emotional receptiveness | |||

| Warmth (+) | 5.6 (1.9) | 6 (1.4) | 0.504 (T) |

| Openness to change (+) | 5.3 (1.7) | 5.8 (1.7) | 0.247 (T) |

| Social receptiveness | |||

| Warmth (+) | 5.6 (1.9) | 6 (1.4) | 0.504 (T) |

| Stability (−) | 5.2 (1.3) | 4.8 (1.1) | 0.504 (U) |

| Apprehension (+) | 6.2 (1.6) | 6.3 (1.8) | 0.770 (T) |

| Boldness (−) | 5.1 (2.1) | 5.4 (1.6) | 0.882 |

| Openness to change (−) | 5.3 (1.7) | 5.8 (1.7) | 0.247 |

| Tension (−) | 5.7 (1.6) | 6.4 (1.5) | 0.095 |

| Emotional control | |||

| Reasoning (+) | 6.1 (1.5) | 6.1 (1.2) | 0.735 (U) |

| Privateness (+) | 5.9 (2.2) | 5.9 (1.7) | 0.901 (U) |

| Apprehension (v) | 6.2 (1.6) | 6.3 (1.8) | 0.770 (T) |

| Social control | |||

| Reasoning (+) | 6.1 (1.5) | 6.1 (1.2) | 0.735 (U) |

| Dominance (+) | 4.6 (1.8) | 6.4 (1.6) | <0.001 (U) |

| Boldness (+) | 5.1 (2.1) | 5.4 (1.6) | 0.882 (U) |

| Vigilance (−) | 5.5 (1.5) | 5.6 (1.6) | 0.995 (U) |

| Openness to change (+) | 5.3 (1.7) | 5.8 (1.7) | 0.247 (T) |

| Accuracy (+) | 4.9 (1.2) | 5.5 (1.6) | 0.056 (U) |

The data provided related to the average value and the standard deviation (SD). The statistical tests used were Student's t test (T) and the Mann–Whitney U-test (U).

The statistic significance level in this study is p<0.05.

The + symbol shows that the average score was above that of the Spanish population average (5.5 points). The − symbol shows that the average score was below such average.

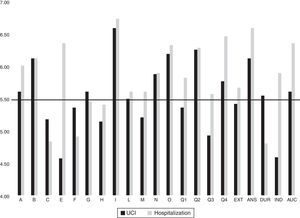

When analysing social skills, looking at the 6 scales described by Riggio,11 and as has been shown in Table 3, in the ICU group, the factors associated with such skills with scores above or below the population average were the following: tension +, warmth +, stability −, apprehension +, boldness −, openness to change −, reasoning + and privateness +. In the Admissions group, the factors associated with social skills they had were the following: dominance +, rule-consciousness −, tension +, openness to change +, warmth +, stability −, apprehension +, boldness −, reasoning + and privateness + (Fig. 1).

The comparison between each of the factors that make up the social skills for communication between the two groups analysed, ICU and Admissions, showed the existence of a statistically significant difference in favour of the professionals in the Admissions group regarding dominance.

DiscussionIn this study it can be seen that the percentage of women working both in the ICU group (89.6%) and the Admissions group (85%) is very high. It is even higher than the percentage of female nurses registered in the Autonomous Community of Madrid, provided by the Spanish National Statistics Institute for 2014, which was 84.4%.17 There are studies that show that women have better skills than men when it comes to listening to personal and professional problems, as well as creating a good environment that promotes communication, exchange and participation.18

From the results obtained in the 6 dimensions connected to social skills, we saw that the ICU nurses had scores lower than the population average in emotional expressivity, social expressivity, social receptivity and social control. They only have a score above the population average (5.5 points) in one trait associated with emotional expressivity, which is tension (Q4+); no traits associated with social expressivity; just one trait associated with emotional receptivity, which is warmth (A+) and one trait associated with social control, reasoning (B+). The ICU nurses did however have traits associated with social receptiveness, where they had 5 out of 6 possible traits: warmth (A+), stability (C−), apprehension (O+), boldness (H−) and openness to change (Q1−), and with emotional control they had two out of three possible traits: reasoning (B+) and privateness (N+).

These personality factors, associated with social skills found in ICU nurses in the study group, would be characteristic of professionals with the following personality traits: energetic and impatient professionals, warm and generous with other people, abstract thinkers, reactive and emotionally changeable, apprehensive and anxious, bold and proactive, traditional and family-orientated, calculating and discrete.

Comparing the ICU nurses group to the Admissions nurses group, we can see that the Admissions nurses had behavioural traits associated with emotional expressivity, emotional receptivity, social receptivity, emotional control and social control; they are lacking in social expressivity. Therefore, we could say that, on a global level, they had more personality factors linked to social skills and are more developed in these skills compared to ICU nurses.

In this respect, it should be pointed out that with the nurses in the ICU group, all the dimensions with both emotional and social components were below the scores for the nurses in the Admissions group, which could be due to the fact that these professionals do not develop these skills since they tend to work with patients that cannot easily establish fluid conversation, which would promote communication exchange.1 However, these skills are essential in the relationship with close relatives, which are highly valued by the relatives of critically ill patients,19 with a strong impact on how they perceive care.

Nurses in the ICU group did have a high score for social receptiveness, in other words, the ability that allows them to take in information with a verbal component. This may be due to the level of exactness and the specificity of the type of communication that there is in a unit such as an ICU, where all the instructions, protocols, internal communications, team work, etc., mean that the information received needs to be understood perfectly and carried out without any doubts whatsoever, rapidly and efficiently. These skills are not so developed in the nurses in the Admissions group, although the difference between the two groups does not cause any statistical significance.

Trying to find reasons behind the results obtained, regarding the social skills for communication in the nurses working in the ICU, it is plausible that the specific nature of their work, as well as the stress caused by life-or-death situations means that all aspects of non-verbal communication, (in other words, based on emotions), is not so developed or even repressed in these professionals. This may be a personality defence mechanism,20 created by the individual when faced with situations that they may experience in their daily work life, such ask stressful situations, focussing on promoting communication with a verbal element, which is what they require in their daily work.

Our results fit with those from other studies, where there were also deficiencies in social skills among care nurses. Out of these we would like to highlight the work of Gómez Gómez19 and Broyles et al.,21 related to social skills for communication, in which it was found that existing communications models between professionals and relatives were insufficient and unsatisfactory. Our results, however, go against the results obtained in the Ramos López18 study, since the sample in our study was mainly women, we have not found that they develop a good environment to promote communication.

As an alternative to improving social skills among ICU nurses, we propose professional meetings with the relatives of patients admitted to the ICU, much like Daly et al.,22 since this is a context that allows for communication between professionals and relatives to be held, gaining active listening and communication skills and getting better participation and satisfaction from both professionals and relatives.

Other areas for improvement based on the results of the study could be to implement educational actions to talk about communication skills, emotional understanding and verbal and non-verbal elements of communication in their professional lives.1 Specific training on social and communication skills could improve the personality traits that we have seen to be deficient in the study group, a proposal that matched with that put forth by Sargeant et al.23 and Pades.24 The evidence suggests that communication should be tackled from an interdisciplinary perspective for optimum efficiency. For such purpose, all the health-care team must be trained and have the necessary skills.25

In summary, we wish to point out that the personality traits associated with social skills in ICU nurses found in this study are lower than those found in Admissions nurses. We believe that it is essential to intervene and give specific training to develop social skills among ICU nurses.

As far as future lines of investigation are concerned, we suggest increasing the sample size, having a greater number of professionals working in ICU units and Admissions units, as well as extending the study to a greater number of hospitals and Autonomous Communities. This will help to obtain data to complement this study and open up new perspectives for research in this field.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors state that the procedures carried out are in line with the standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation, the World Medical Association and the Helsinki Declaration.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors state that they have followed the protocol of their work centre regarding the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that none of the patients’ data appears in this article.

FundingThe authors of this project state that they have had no financial aid or any other type of aid from any institution or organisation, either public or private.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interests.

Please cite this article as: Ayuso-Murillo D, Colomer-Sánchez A, Herrera-Peco I. Habilidades de comunicación en enfermeras de UCI y de Hospitalización de adultos. Enferm Intensiva. 2017;28:105–113.